Background: Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) encompasses a spectrum of clinical phenotypes, the origin of which has not been fully elucidated.

Results: Cell-free prion protein misfolding by sporadic CJD subtypes was affected by brain tissue composition and not related to absolute levels of PrPC.

Conclusion: Tissue environment contributes to CJD subtype-specific prion protein misfolding.

Significance: Non-PrPC cofactors may contribute to the development of sporadic CJD.

Keywords: Brain, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Prions, Protein Misfolding, Tissue Factor, Conversion, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, PrP, Sporadic, Subtype

Abstract

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is the most prevalent manifestation of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or prion diseases affecting humans. The disease encompasses a spectrum of clinical phenotypes that have been correlated with molecular subtypes that are characterized by the molecular mass of the protease-resistant fragment of the disease-related conformation of the prion protein and a polymorphism at codon 129 of the gene encoding the prion protein. A cell-free assay of prion protein misfolding was used to investigate the ability of these sporadic CJD molecular subtypes to propagate using brain-derived sources of the cellular prion protein (PrPC). This study confirmed the presence of three distinct sporadic CJD molecular subtypes with PrPC substrate requirements that reflected their codon 129 associations in vivo. However, the ability of a sporadic CJD molecular subtype to use a specific PrPC substrate was not determined solely by codon 129 as the efficiency of prion propagation was also influenced by the composition of the brain tissue from which the PrPC substrate was sourced, thus indicating that nuances in PrPC or additional factors may determine sporadic CJD subtype. The results of this study will aid in the design of diagnostic assays that can detect prion disease across the diversity of sporadic CJD subtypes.

Introduction

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD)4 is the most prevalent manifestation of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy or prion diseases affecting humans. Unlike familial CJD, invariably associated with mutations in the prion protein gene (PRNP) and acquired forms of CJD, including iatrogenic and variant CJD, the etiology of sCJD is unknown (for review, see Ref. 1). However, once extant, all forms of the disease are transmissible, with potential transmission events during the provision of medical care posing a continuing public health concern (2–10).

The transmissible nature of prion disease has been attributed to the template-directed misfolding of the normal cellular prion protein (PrPC) by the disease-associated conformation (PrPSc). This misfolding event is associated with an increase in protease resistance and β-sheet content of the protein (for review, see Ref. 1). Unlike conventional infectious agents such as viruses or bacteria, the infectious agent of prion disease, the “prion,” does not have a nucleic acid genome and is proposed to be composed principally of PrPSc (11).

Prion diseases occur with distinct and transmissible stable clinical profiles that are associated with characteristic neuropathological features (12). These strain-like properties have been correlated with distinct electrophoretic patterns of PrPSc on Western blots following protease digestion (13) that are believed to reflect unique prion protein conformations and modifications (14). In human diseases this is most pronounced in CJD, where these differences are used diagnostically to identify sporadic and variant CJD (15–17). The disease defined as sCJD evinces phenotypic diversity, with PrPSc electrophoretic mobility and allelic variation at codon 129 contributing to the further grouping of cases into unique molecular subtypes, which correlate with unique clinical profiles and neuropathology (15, 16, 18, 19).

The misfolding of PrPC into a protease-resistant form (PrPres) can be reproduced in vitro using a mammalian or recombinant source of PrPC and PrPSc derived from the brains of prion-affected animals (20, 21) and has shown that this misfolding event can generate an infectious and pathogenic entity (20, 22). These assays have been proposed as candidates for preclinical screening in both agricultural and health care settings and have been used successfully to detect low levels of prions in defined animal models of prion disease (23, 24) and CSF fluid of patients with clinically confirmed CJD (25). However, even within defined animal models the requirements for efficient and specific prion replication have been shown to vary. Although misfolding of PrP can occur in the absence of host-derived factors (20), the efficiency of the process is greatly improved when these putative factors are provided in trans in the form of a crude brain homogenate (26, 27). Attempts to define these cofactors have identified a role for polyanions, and in particular ribonucleic acids (28–30). However, the contribution of ribonucleic acids to the conversion process has also been shown to have species- and prion strain-specific effects (31, 32). The purpose of the current study was to define more fully the substrate requirements for sCJD PrPSc molecular subtype replication using a simple in vitro amplification assay, requiring minimal manipulation of human brain-derived seed and substrate.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Brain Tissue Selection

The use of human tissue for this study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. Samples of brain tissue were taken from the frontal cortex of sCJD cases that had been subtyped on the basis of PrPSc electrophoretic mobility and codon 129 genotype by the Australian National CJD Registry (ANCJDR) as described previously (17). Data sets involved three cases each of type 1 and type 2 codon 129 methionine homozygote PrPSc, respectively, and two cases each of type 3 codon 129 valine and methionine homozygotes PrPSc (19). Tissue from the frontal cortex of 47 brains obtained from patients without documented neurodegenerative conditions were obtained through the Victorian branch of the Australian Brain Bank Network (ABBN).

The use of animals in this study was approved by the University of Melbourne Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee. All procedures were performed while animals were anesthetized (methoxyflurane), and animals were ethically culled prior to tissue collection. Brains were collected from BALB/c mice in the terminal stage of disease following intracerebral inoculation with M1000 prions (33) as well as from uninoculated wild type BALB/c (Animal Resource Centre, Western Australia) and Prnp knock-out (Prnp−/−) (34) mice.

Extraction of DNA

Genomic DNA, extracted from 50–100 mg of brain tissue using standard phenol/chloroform extraction methods, was PCR-amplified and the genotype at codon 129 genotype determined by restriction endonuclease BbrPI digestion as described previously (35).

Homogenate Preparation

A 10% (w/v) homogenate was prepared from sCJD brain tissue or M1000-infected mouse brain tissue in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (DPBST) by homogenization through a graded series of blunt ended needles to 26 gauge and cleared of debris by centrifugation at 200 × g for 30 s. Aliquots of the cleared homogenate were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Uninfected brain tissue to be used as a PrPC substrate was macroscopically dissected into gray and white matter components and prepared as 10% (w/v) homogenates in DPBS containing EDTA-free eComplete Protease Inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) using a 3-ml Dounce homogenizer. The homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at 200 × g for 2 min, and aliquots of the cleared homogenate were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Protease Digestion

Sporadic CJD brain homogenates were digested with 100 μg/ml proteinase K (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37 °C and the reaction stopped by the addition of Pefabloc to 4 mm (Roche Applied Science) and incubation on ice. Samples were treated for 5 min at 37 °C with Benzonase (1 unit/μl; Merck) in the presence of 10 mm Mg2Cl before the addition of 2× LDS loading dye (Invitrogen) containing 6% β-mercaptoethanol in preparation for SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

Cell-free in Vitro Conversion Activity Assay

The cell-free in vitro conversion activity assay (CAA) was performed as described (32); however, the infected brain homogenate used to seed the conversion reaction was pretreated with proteinase K (PK) to remove any protease-sensitive PrP prior to use in the CAA. Briefly, for pre-protease treatment (PPT) the 10% (w/v) sCJD brain homogenates were treated with PK as described above and the reaction stopped by the addition of 4 mm Pefabloc. Samples were diluted in DPBST and centrifuged at maximum speed (∼21,000 × g) in a benchtop centrifuge for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing PK and Pefabloc was removed, and the pellet containing insoluble, protease-resistant PrP was resuspended to the appropriate dilution in DPBST.

The prepared PPT sCJD brain homogenates were added to an equal volume of 10% (w/v) uninfected brain homogenate in DPBS/protease inhibitors. Each reaction was prepared in duplicate. An equal volume of each sample was then divided into two, with one sample incubated overnight (∼16 h) in a shaking incubator (300 rpm) at 37 °C and the other sample snap frozen and stored at −80 °C serving as the frozen control for the duration of the incubation period. At the end of the incubation period the frozen sample was thawed and the protease-sensitive PrP present in both frozen and incubated samples digested with PK as described above in preparation for SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

Western Immunoblot Analysis

Samples prepared in LDS loading dye were heated to 100 °C for 10 min and then electrophoresed on 12% (bis-tris) gels (NuPAGE, Invitrogen) in MES buffer (Invitrogen) for 50 min at a constant 200 V. Protein was transferred to a prepared PVDF membrane using wet blotting apparatus (Criterion Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer (25 mm Tris, 200 mm glycine, 20% methanol) at a constant voltage (70 V) for 1 h at 4 °C. Membranes were then blocked in 5%(w/v) nonfat milk powder prepared in PBS containing Triton X-100 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then probed with the primary monoclonal antibody 3F4 (36) diluted 1:5,000 in PBST overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed 3 × 10 min with PBST and incubated with anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (GE Healthcare) diluted 1:15,000 in PBST for 1 h at room temperature before being developed with ECL Plus (GE Healthcare) for 5 min at room temperature and then imaged using LAS3000 Imager (Fujifilm), quantified using Multi Gauge version 3.0 software (Fujifilm), with graphical presentation and statistical analysis performed using Prism 4 (GraphPad software).

Western immunoblot analysis of reactions using the mouse-adapted M1000 prion strain PrP was detected with a polyclonal antibody raised against residues 89–103 of mouse PrP (03R19; (37)). NeuN was detected using a mouse anti-NeuN monoclonal antibody (Millipore; MAB377, A60), and myelin basic protein (MBP) was detected using a rabbit anti-MBP polyclonal antibody (DAKO; A0623). Dot-blot detection of heparan sulfate was performed using 10E4 (Seikagaku Corporation) (38), a mouse monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes the N-sulfated glucosamine residues present in heparan sulfate.

RESULTS

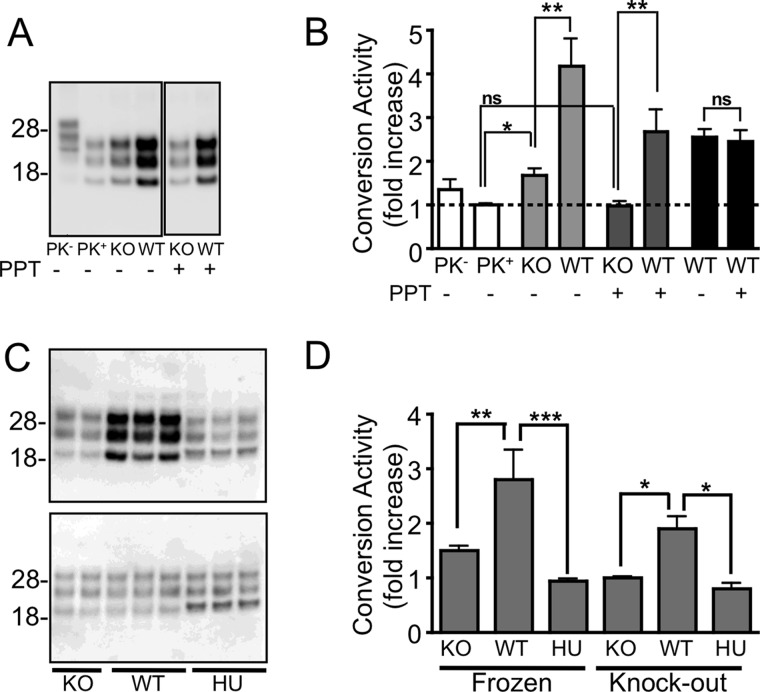

Cell-free Propagation of PrPres by the Protease-resistant Core of PrPSc

A cell-free, in vitro, CAA was used to specifically determine the conversion activity of a particular PrPC substrate when presented with a PrPSc seed derived from a prion-infected brain homogenate. In this assay the infected brain homogenate, which acts as a seed to initiate PrPres formation, is first PK-treated to remove any protease-sensitive PrP. This pretreatment militates against any PrPC accompanying the PrPSc seed being used preferentially as a substrate in the reaction or interfering with the conversion process. Evidence that this source of PrPC can act as substrate was observed when Prnp−/− brain homogenates were added to non-PK-treated sources of mouse-derived PrPSc (Fig. 1A). Under these conditions a small, but significant increase in PrPres was detected relative to the same source of PrPSc in buffer alone (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Species-specific formation of PrPres using the insoluble protease-resistant core of PrPSc. A and B, Western immunoblotting (A) and quantitation (B) of in vitro conversion activity assay using an M1000 prion-infected brain homogenate with (+) and without (−) PPT. The small but significant (p < 0.01; t test) increase in PrPres generated in the presence of a Prnp−/− (KO) brain homogenate from untreated PrPSc (light gray bars) relative to the same PrPSc seed diluted in DPBS (clear bars, PK+) was not seen after PPT (dark gray bars) but could form PrPres from a wild type mouse brain homogenate (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, t test). The conversion activity of PrPSc with and without PPT did not significantly differ (p = 0.8015; two-tailed t test) when the -fold increase was calculated relative to their respective knock-out controls (black bars), indicating that PPT did not affect the ability of PrPSc to seed a conversion reaction. C, PPT of a M1000 prion-infected brain homogenate allowing increased production of PrPres (upper blot) from a substrate derived from wild type mouse brain (WT) but not from a Prnp−/− (KO) or human brain (HU) homogenate when incubated at 37 °C. No increase in PrPres was detected from matching reactions frozen at −80 °C (lower blot). D, quantitation of conversion activity as a -fold increase over the frozen sample or relative to the KO substrate showing significant conversion activity by substrate containing murine PrPC. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test. Error bars, S.E.

To prevent subsequent degradation of the PrPC substrate by PK, following digestion the seed was centrifuged and the resulting protease-resistant insoluble pellet resuspended in conversion buffer and sonicated before it was used as the seed in the CAA. The protease-resistant insoluble component of a prion-infected mouse brain homogenate was able to efficiently generate PrPres from a WT mouse brain homogenate (Fig. 1B). Importantly, an increase in PrPres was only observed when samples were incubated at 37 °C, in the presence of a murine, but not human, PrPC substrate (Fig. 1, C and D), thus confirming the ability of this assay to preserve the species barrier and therefore faithfully mimic the in vivo attributes of prion disease.

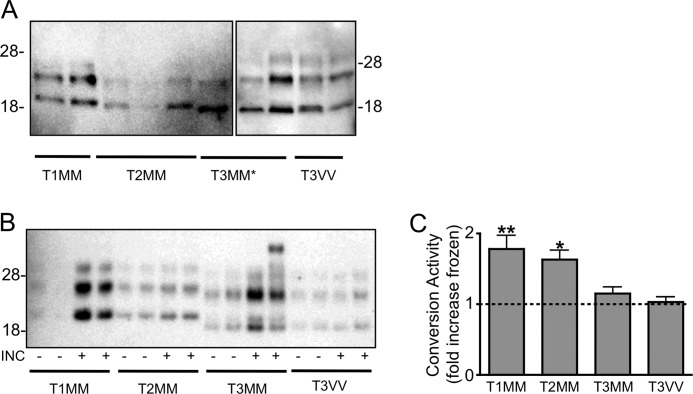

Sporadic CJD PrPSc Is Able to Generate PrPres from Codon 129 Homologous Substrate

To investigate the substrate specificity of sCJD molecular subtypes, homogenates were prepared from brain tissue of patients with different molecular subtypes as determined by the ANCJDR. The prevalence of each strain type in the Australian population is summarized in Table 1. The classification of cases used is: T1MM (n = 3), T2MM (n = 3), T3MM (n = 2), and T3VV (n = 3), which was confirmed by electrophoretic mobility of PrP after PK digestion (Fig. 2A). The PK-resistant, insoluble component of each sample was used to seed a PrPC substrate prepared from a pool of methionine homozygous control brain tissue homogenates (n = 3). Concordant with their genotype, an increase in PrPres was detected in reactions utilizing methionine homozygous seeds (T1MM, T2MM, and T3MM) but not valine homozygous seeds (T3VV), and the eletrophoretic mobility of the PrPres generated from each methionine homozygous sample was consistent with the seed from which it was generated (Fig. 2B). Quantitation of the -fold increase in PrPres from the CAA of incubated samples over frozen indicated significant conversion activity for T1MM (p < 0.01) and T2MM (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2C).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of sporadic CJD molecular subtypes in Australia (adapted from ANCJDR Annual Report)

| Genotype proportion in study populationa,b | Codon 129 genotype | Sporadic CJD PrPSc subtypeb |

Total spCJD typeb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 24 (52.2) | MM | 27 (22.7) | 46 (38.7) | 9 (7.6) | 82 (68.9) |

| 19 (43.3) | MV | 3 (2.5) | 4 (2.8) | 17 (14.3) | 24 (20.2) |

| 3 (6.5) | VV | 13 (10.9) | 13 (10.9) | ||

| Total | 30 (25.2) | 50 (42.0) | 39 (32.8) | ||

a Determined in the current study from 46 tissue donors to the ABBN.

b Percentage of indicated group (%).

FIGURE 2.

Sporadic CJD PrPSc seeding PrPres in the CAA is strain- and substrate-dependent. A, sporadic CJD molecular subtypes classified as type 1 (T1), 2 (T2), or 3 (T3) on the basis of electrophoretic mobility on a Tris/glycine gel after protease digestion (representatives of each subtype shown). T3MM* samples in last lane of left panel are the same as the first lane in the right panel to show the relative electrophoretic mobility. Blots were probed with 3F4. B and C, representative Western immunoblot (B) and quantitation (C) of conversion activity using seeds from each sporadic CJD subtype (T1MM, T2MM, T3MM, and T3VV) over a pool of methionine homozygous PrPC substrates. Samples were incubated (INC) at 37 °C (+) or frozen at −80 °C (−). Conversion activity is shown as the mean -fold increase PrPres generated from incubated compared with frozen samples. Significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01) was calculated relative to the mean conversion activity detected in the presence of a mouse brain homogenate using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test. Error bars, S.E.

To investigate further the substrate specificity of sCJD PrPSc the CAA was performed using uninfected brain tissue with different codon 129 genotypes. The codon 129 genotype was successfully determined for 46 of the 47 cases (Table 1), and tissue from two brains with the MM and MV genotype and the three identified VV cases was included in further analyses. To investigate the substrate composition and reduce sample variability, samples were macroscopically dissected into gray and white matter.

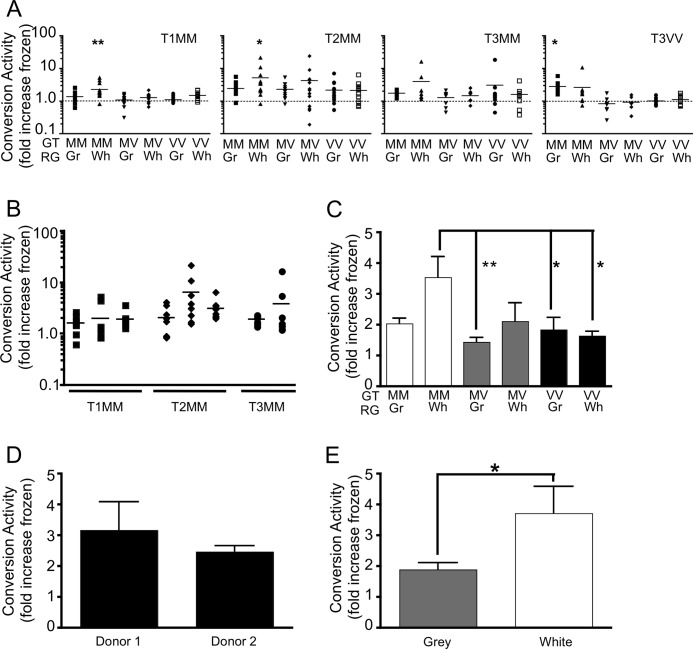

Each of these samples was used as a substrate for duplicate conversion reactions performed over at least two cases of sCJD PrPSc seed. Conversion activity was calculated as the -fold increase over a matched sample frozen at −80 °C for the duration of the reaction. Fig. 3 presents the conversion activity of each sCJD PrPSc in combination with each substrate. Samples with a conversion activity >1 represent an increase in PrPres in incubated compared with frozen reactions. In addition, each experiment was performed using a mouse brain homogenate as the PrPC substrate, where there would be no conversion detected with the human-specific monoclonal antibody 3F4. This control was included to address any nonspecific change in protease resistance of the sCJD brain homogenates in the presence of a brain homogenate. Statistical analysis was performed relative to this more stringent control. T1MM sCJD PrPSc showed a significant preference for the methionine homozygous PrPC substrate without significant levels of PrPres generated from the PrPC substrate of other codon 129 genotypes.

FIGURE 3.

Sporadic CJD PrPSc has PrP genotype and brain region-specific requirements for in vitro conversion activity. A, protease-pretreated sporadic CJD PrPSc (T1MM, T2MM, T3MM, and T3VV) used to generate PrPres from a PrPC substrate enriched for the gray (Gr) or white (Wh) matter regions (RG) of brain tissue with a PrP codon 129 genotype (GT) either MM, MV, or VV. Conversion activity is the -fold increase in PrPres for each incubated sample over its corresponding control frozen sample. The dotted line indicates no conversion activity. Significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01) was calculated relative to the mean conversion activity detected in the presence of a mouse brain homogenate using one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test. B, conversion activity of individual sources of T1MM (n = 3), T2MM (n = 3), and T3MM (n = 2) sporadic CJD PrPSc using PrPC substrate from gray and white matter of the methionine homozygous donors. C, ability of PrPC substrates with different codon 129 genotypes and derived from different brain regions to support PrPres formation by any sporadic CJD subtype. D, ability of methionine homozygous PrPC substrates derived from the gray and white matter of two different donors, to support the conversion activity of T1MM and T2MM PrPSc. E, conversion activity of gray and white matter-enriched methionine homozygous substrates seeded with T1MM and T2MM sporadic CJD PrPSc. Error bars, S.E.

In contrast, the T2MM sCJD PrPSc appeared to have a broader substrate tolerance, with a mean conversion activity >2 for each substrate, although this was only found to be significant for methionine homozygous samples. Consistent with its generally poor performance over the MM substrate pool, T3MM did not significantly convert any PrPC substrates. Somewhat surprisingly, the T3VV seeds were able to generate PrPres from individual methionine homozygous samples, but not from the homologous valine homozygous PrPC substrates.

The Effect of Donor Variation on Conversion Activity

There was no significant difference in the ability of individual methionine homozygous PrPSc seeds (T1, T2, T3) to generate PrPres from the methionine homozygous PrPC substrates (gray and white matter-enriched) (Fig. 3B). To investigate the effect that the codon 129 genotype has on the susceptibility of the substrate to permit PrPres formation, the conversion activities of each PrPC substrate for all sporadic CJD PrPSc sources were compared. Conversion activity was greatest for methionine homozygous PrPC (Fig. 3C).

To determine the susceptibility of PrPC from different donors to provide a substrate for conversion, the conversion activities of the two codon 129 methionine homozygous sources of PrPC were investigated. There was no difference in the ability of PrPC sourced from different donors to support PrPres formation by T1MM and T2MM PrPSc seeds (Fig. 3D).

However, differences were observed in the ability of PrPC, derived from simple macroscopic separation into gray or white matter-enriched substrates, to support PrPres formation. In particular, a preference was observed for codon 129 methionine homozygous PrPSc for white matter-enriched codon 129 methionine homozygous substrate and a preference of the codon 129 valine homozygous PrPSc for gray matter-enriched methionine homozygous substrate (Fig. 3A). This preference was most apparent when the conversion of T1MM and T2MM sporadic CJD strains were examined (Fig. 3E).

Brain Region Variation in PrPC Processing May Contribute to PrPres Formation

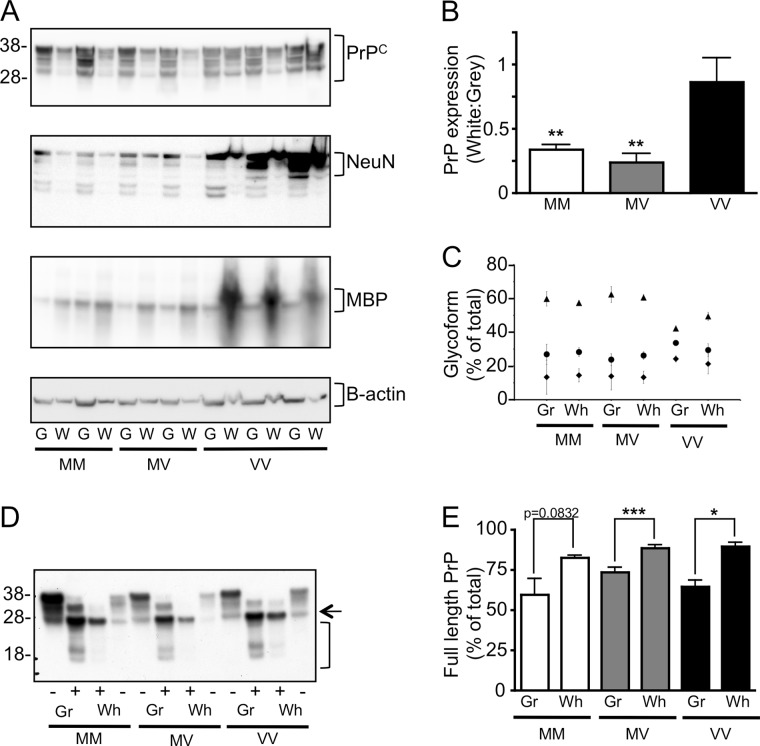

To understand the molecular basis of the brain region-specific ability of PrPC to influence PrPres formation in the CAA, the PrPC in gray and white matter-enriched homogenates was examined. Western immunoblot analysis of our simple, component-specific brain separations confirmed the enrichment of gray matter using the neuronal nuclear protein marker NeuN and of white matter using the axonal marker MBP (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of PrPC substrate. A, gray (G) and white (W) matter-enriched homogenates prepared from each PrP genotype showed increased NeuN and MBP reactivity, respectively, and similar levels of β-actin. B, the ratio of PrP expression in white:gray-enriched brain indicated that there was more PrP present in gray matter-enriched brain from MM and MV PrPC substrates, but unchanged in the VV PrPC substrate. C, the proportions (%) of di- (triangles), mono- (circles), and unglycoslated (diamonds) forms of PrPC were calculated from the Western immunoblot (mean ± S.E. (error bars)). D, Western immunoblotting was performed of homogenates enriched for gray and white matter from MM, MV, and VV PrPC substrates treated with (+) or without (−) peptide:N-glycosidase F and probed with 3F4. E, full-length PrP (arrow) and truncated PrP (bracket) were quantified and are shown as the percentage full-length of total. For each analysis n = 4 (MM), n = 5 (MV), n = 3 (VV). Significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; t test) was calculated for each glycotype. Error bars, S.E.

Western immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4A) and quantitation (data not shown) of PrPC present in each 10% w/v substrate indicated that there was no significant difference in the amount of PrPC present in gray matter-enriched tissue prepared from the different codon 129 substrates or a difference in total PrPC expressed in combined gray and white matter-enriched tissue. However, for the codon 129 methionine homozygous and heterozygous substrates there was significantly more PrPC present in tissue enriched for gray versus white matter (Fig. 4B), and both of these genotypes also had similar patterns of glycosylation (Fig. 4C). In contrast, similar levels of PrPC were present in both gray and white matter-enriched homogenates prepared from codon 129 valine homozygous brain tissue, and the PrPC from this genotype had a significantly more unglycosylated and less diglycosylated PrPC relative to the other genotypes. There was no difference in glycoforms between PrPC from gray or white matter regions.

It has been reported that cell lines that are more susceptible to prion infection harbor significantly greater ratios of full-length to C1 PrP (39). For all genotypes investigated the proportion of full-length PrP relative to truncated species (C1 and C2) was greater in white versus gray matter (Fig. 4, D and E).

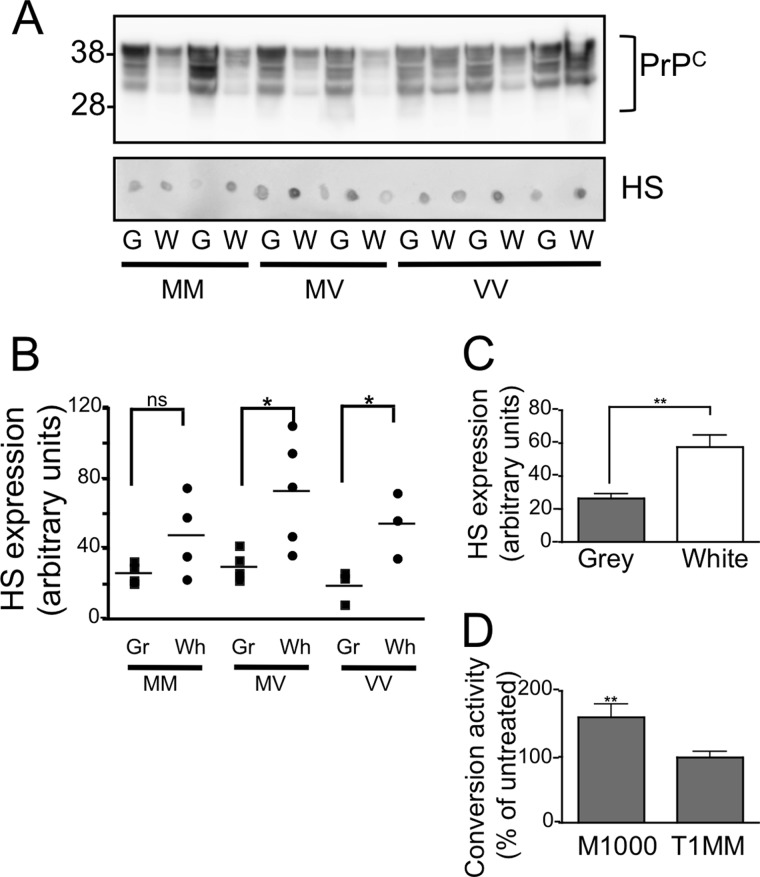

PrPC-independent factors may also contribute to the region-specific ability of PrPC to act as a more permissive substrate in the CAA. Depletion of heparan sulfate from mouse-derived brain tissue has been shown to abrogate the conversion activity of the mouse-adapted human prion strain, M1000 (32). Human-derived brain tissue showed a brain region-specific difference in reactivity to the heparan sulfate-specific antibody 10E4, with significantly more heparan sulfate detected in white matter-enriched samples (Fig. 5, A and C). No codon 129 genotype-specific difference was observed (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Contribution of heparan sulfate (HS) to conversion activity of sporadic CJD PrPSc. A, heparan sulfate was detected by dot blot analysis of gray (G) and white (W) matter-enriched homogenates prepared from MM, MV, and VV using 10E4. B and C, 10E4 reactivity for gray and white matter-enriched homogenates of each genotype (n = 3; MM, n = 4; MV, n = 3, VV) (B) or gray and white-enriched homogenates of combined genotypes (n = 10) (C) was quantified. D, the addition of 50 ng/ml pentosan polysulfate to the CAA reaction significantly enhanced the conversion activity of M1000 PrPSc over a murine substrate but had no effect on T1MM PrPSc conversion of a MM gray matter-enriched substrate. Significance was calculated (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 t test) for the indicated data sets. Error bars, S.E.

To investigate whether the presence of heparan sulfate may be contributing to the enhanced ability of white matter to support PrPres formation by MM sporadic CJD PrPSc seeds, we used pentosan polysulfate as a heparan sulfate mimetic to stimulate PrPres formation from codon 129 methionine homozygous gray matter PrPC substrate driven by a T1MM seed. Whereas the addition of 50 ng/ml pentosan polysulfate significantly increased the conversion activity of a mouse-derived prion strain it failed to increase the conversion activity of the human T1MM product (Fig. 5D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, a simple cell-free CAA was used to investigate the role of the polymorphism at codon 129 of PRNP and brain-derived environment on the de novo generation of PrPres from sCJD PrPSc molecular subtype. This study reports the ability of multiple sCJD PrPSc subtypes to induce the conversion of PrPC substrates sourced from human brain into PrPres. This has enabled an unprecedented investigation of the human sCJD molecular subtypes and human host-dependent determinants of prion propagation and demonstrated the enhanced susceptibility of codon 129 methionine homozygous PrPC to a PrPSc-induced change in conformation even when the molecular subtype of the PrPSc seed is valine homozygous. The selective enrichment of the PrPC substrate from gray or white matter components of the frontal cortex revealed brain composition-specific differences, which were not related to absolute levels of PrPC expression.

The sCJD molecular subtypes used in this study were classified by the ANCJDR in accordance with the classification system defined by Collinge et al. (16). In this classification system, three types of sCJD PrPSc are defined by differences in their Western blot electrophoretic mobility after PK digestion, with ultimate subtype determined in combination with the genotype of codon 129. This system identifies a distinct sCJD subtype, T1MM, which is almost exclusively associated with methionine homozygosity at codon 129 and is phenotypically characterized by a short clinical duration and distinctive neuropathology (19). The present study corroborates the unique classification of the T1MM sCJD subtype, by the restricted ability of PrPSc of this subtype to convert only a methionine homozygous PrPC substrate and high levels of conversion of a methionine homozygous PrPC pool. This pattern was significantly different from the conversion profile of the sCJD subtypes classified as T2MM in this study (paired t test p < 0.05), which had a mean conversion activity of >2 for each of the genotypes of the PrPC substrate tested. This pattern of conversion activity is consistent with the association of this strain with all codon 129 genotypes, albeit most efficiently and significantly from a white matter-enriched methionine homozygous PrPC substrate.

There were some interesting and unexpected differences in the composition of valine homozygous substrates, which may contribute to the altered susceptibility of this genotype to prion disease. Unlike codon 129 methionine homozygous and heterozygous samples, valine homozygous samples contained similar levels of PrPC in both gray and white matter-enriched preparations and a greater proportion of unglycosylated PrP. It remains to be determined how these differences may contribute to the susceptibility of PrP to conversion, but our data suggest a functional role for codon 129 polymorphism in human PrPC expression.

As expected and previously reported (40, 41) the valine homozygous sCJD molecular subtype was unable to generate PrPres from a pool of methionine homozygous PrPC. However, when conversion was performed over individual methionine homozygous substrates, a significant level of conversion activity was observed for the gray matter-enriched regions. This unexpected result may reflect the prevalence of the methionine homozygous PrPC allele within the sCJD population and our own result from Fig. 3C, which indicates that this substrate is the most susceptible to conversion. In contrast the valine homozygous PrPC allele is poorly represented in the sCJD population and was not a good substrate in the current study. As for the inability for conversion to have occurred in a pool of methionine homozygous homogenate composed of both gray and white matter we can only speculate that a cofactor present in this combined brain homogenate was either inhibitory to the conversion or not present in sufficient concentrations to enhance conversion.

There was no overall difference in the ability of PrPC from different donors to act as a substrate for sCJD subtype propagation. However, there was a brain region-specific difference in the ability of codon 129 methionine homozygous substrate to support the propagation of methionine homozygous seeds. Despite acting as a better substrate, white matter-enriched brain tissue had less PrPC than the gray matter-enriched substrate. In the presence of PrPSc seed, PrPC expression is essential but not necessarily sufficient for prion propagation in vivo (34), in vitro (42, 43), and in cell-free assays (Ref. 32 and present study). Indeed, high levels of PrPC expression do not correlate with the susceptibility of cell lines to propagate prion infection, and we have shown that the use of a PrP-overexpressing mouse brain tissue as the substrate in the CAA does not lead to a proportional increase in conversion activity (32). These observations point to a more complex determinant of prion propagation, such as the contribution of non-PrPC cofactors.

Several polyanions have been implicated as cofactors in prion propagation. Nucleic acids and glycosaminoglycans have been shown to alter the conformation of recombinant PrP (44, 45) which has been proposed as a mechanism where by the free-energy barrier can be lowered thus facilitating the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc (46). RNA, a molecule that appears to catalyze the spontaneous misfolding of PrP into an infectious form, has been proposed to have species- and strain-dependent requirements. RNA has been shown to be essential for the cell-free propagation of hamster scrapie strains and a mouse-adapted human prion strain but not a mouse-adapted scrapie strain (28, 31, 32). Similar prion strain-specific requirements may contribute to the profile of sCJD molecular subtypes.

The polyanion heparan sulfate was also enriched in white matter-derived brain tissue. However, addition of the heparan sulfate mimetic pentosan polysulfate, which we have shown to stimulate conversion of mouse-derived PrPC by the mouse-adapted human prion strain M1000, did not enhance the conversion of gray matter-derived PrPC by T1MM sCJD PrPSc. This observation further attests to the species and strain-specific cofactor requirements of prion propagation (28, 31, 32), which may contribute to the strain-specific efficacy of anti-prion therapeutics.

Although not investigated here, homogenates prepared from white matter-enriched human brain have a greater lipid content than homogenates prepared from gray matter, with increased concentrations of cerebroside and cholesterol reported to be present in white matter (47). Given the recently described role of lipids in the spontaneous generation of infectious prions from a recombinant source of PrP (48) and contribution to the seeded conversion of purified mammalian PrPC (30), the role of this lipid variation in these brain components may contribute to sCJD subtype variation.

PrPC can be glycosylated at either or both of two positions, which results in protein with three distinct glycotypes. Although glycosylation of PrPC is not required for prion propagation (for review, see Ref. 49), the glycosylation state of host PrPC can modulate strain- and species-dependent prion transmission (50–52). In the current study there was no clear association between the robustness of PrP glycotypes as substrate and their glycosylation state. However, it was noted that the codon 129 valine homozygous substrate comprised significantly more unglycosylated PrP, and so this difference cannot be completely excluded as a reason for the overall poor quality of the valine homozygous substrate. Intriguingly, knock-in mouse models that express only unglycosylated forms of PrPC are resistant to peripheral infection with two scrapie strains and have long incubation periods following intracerebral inoculation, suggesting that unglycosylated PrP is a poor substrate for prion replication (51, 52).

PrPC may undergo two post-translational cleavage events resulting in the formation of C1 or C2 cleavage products (53, 54). C2 cleavage is analogous to the fragment associated with disease and enriched in the prion-affected brains. C1 cleavage is associated with the resistance of cell lines to prion infection, whereas susceptible cell lines have a greater proportion of full-length PrPC (39). Consistent with this observation, PrPC derived from white matter, which acted as a better conversion substrate, had significantly more full-length PrP. However, the preference of T3VV PrPSc for gray matter-enriched methionine homozygous substrate may again point to subtype-specific PrPC substrate requirements.

Brain region-specific differences in PrPC glycosylation and protein processing have been previously suggested as determinants of prion strain neuropathology (55). The current study extends these differences to show that not only do region-specific differences in PrPC expression and glycosylation state exist but that variation also exists within components of the same brain region (i.e. the frontal cortex) and can be divided on the basis of expression predominantly in cell bodies (gray matter-enriched) and axons (white matter-enriched). Furthermore, these differences are also dependent on amino acid expressed at codon 129.

A better understanding of the contribution of PrPC processing and brain region to prion propagation could be used to increase the sensitivity of assays currently being developed to detect prion disease in preclinical patients. A recent study that used a real-time quaking-induced conversion assay to detect PrPSc in the CSF of patients with confirmed sCJD using a recombinant methionine homozygous PrP substrate revealed 100% specificity for CJD cases and 80% sensitivity (25). The current study suggests that methionine homozygous full-length PrP is an optimal substrate for amplification of many sCJD molecular strain types; however, identification of additional factors that enhance this template-mediated misfolding may be required to detect preclinical disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bruce Chesebro, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, for the 3F4 monoclonal antibody; Professor Charles Weissmann for the Prnp−/−; Fairlie Hinton, Geoff Pavey, and the Australian Brian Bank Network for tissue used in this study; and members of the Australian National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Registry.

This work was supported by Australia National Health and Medical Research Council Grant NHMRC ID 454546 and by the Melbourne University Research Grant Scheme.

- sCJD

- sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- bis-tris

- bis(2-hydroxyethyl)iminotris(hydroxymethyl)methane

- CAA

- conversion activity assay

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's PBS

- DPBST

- DPBS containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100

- MBP

- myelin basic protein

- PBST

- PBS containing 1.0% Triton X-100

- PK

- proteinase K

- PPT

- pre-protease treatment

- PrP

- prion protein

- PrPC

- cellular PrP

- PrPres

- protease-resistant PrP

- PrPSc

- disease-associated PrP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collins S. J., Lawson V. A., Masters C. L. (2004) Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Lancet 363, 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Editorial team (2007) Fourth case of transfusion-associated vCJD infection in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveillance 12, 3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llewelyn C. A., Hewitt P. E., Knight R. S., Amar K., Cousens S., Mackenzie J., Will R. G. (2004) Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet 363, 417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peden A. H., Head M. W., Ritchie D. L., Bell J. E., Ironside J. W. (2004) Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient. Lancet 364, 527–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wroe S. J., Pal S., Siddique D., Hyare H., Macfarlane R., Joiner S., Linehan J. M., Brandner S., Wadsworth J. D., Hewitt P., Collinge J. (2006) Clinical presentation and pre-mortem diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease associated with blood transfusion: a case report. Lancet 368, 2061–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hewitt P. E., Llewelyn C. A., Mackenzie J., Will R. G. (2006) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and blood transfusion: results of the UK Transfusion Medicine Epidemiological Review study. Vox Sang 91, 221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peden A., McCardle L., Head M. W., Love S., Ward H. J., Cousens S. N., Keeling D. M., Millar C. M., Hill F. G., Ironside J. W. (2010) Variant CJD infection in the spleen of a neurologically asymptomatic UK adult patient with haemophilia. Haemophilia 16, 296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins S., Law M. G., Fletcher A., Boyd A., Kaldor J., Masters C. L. (1999) Surgical treatment and risk of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case-control study. Lancet 353, 693–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahillo-Fernandez I., de Pedro-Cuesta J., Bleda M. J., Cruz M., Mølbak K., Laursen H., Falkenhorst G., Martínez-Martín P., Siden A., and EUROSURGYCJD Research Group (2008) Surgery and risk of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Denmark and Sweden: registry-based case-control studies. Neuroepidemiology 31, 229–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ward H. J., Everington D., Cousens S. N., Smith-Bathgate B., Gillies M., Murray K., Knight R. S., Smith P. G., Will R. G. (2008) Risk factors for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann. Neurol. 63, 347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prusiner S. B. (1982) Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216, 136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruce M. E. (2003) TSE strain variation. Br. Med. Bull. 66, 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bessen R. A., Marsh R. F. (1994) Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 68, 7859–7868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caughey B., Raymond G. J., Bessen R. A. (1998) Strain-dependent differences in β-sheet conformations of abnormal prion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32230–32235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parchi P., Giese A., Capellari S., Brown P., Schulz-Schaeffer W., Windl O., Zerr I., Budka H., Kopp N., Piccardo P., Poser S., Rojiani A., Streichemberger N., Julien J., Vital C., Ghetti B., Gambetti P., Kretzschmar H. (1999) Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann. Neurol. 46, 224–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collinge J., Sidle K. C., Meads J., Ironside J., Hill A. F. (1996) Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of “new variant” CJD. Nature 383, 685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lewis V., Hill A. F., Klug G. M., Boyd A., Masters C. L., Collins S. J. (2005) Australian sporadic CJD analysis supports endogenous determinants of molecular-clinical profiles. Neurology 65, 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bishop M. T., Will R. G., Manson J. C. (2010) Defining sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strains and their transmission properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12005–12010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hill A. F., Joiner S., Wadsworth J. D., Sidle K. C., Bell J. E., Budka H., Ironside J. W., Collinge J. (2003) Molecular classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain 126, 1333–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J. I., Cali I., Surewicz K., Kong Q., Raymond G. J., Atarashi R., Race B., Qing L., Gambetti P., Caughey B., Surewicz W. K. (2010) Mammalian prions generated from bacterially expressed prion protein in the absence of any mammalian cofactors. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14083–14087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kocisko D. A., Come J. H., Priola S. A., Chesebro B., Raymond G. J., Lansbury P. T., Caughey B. (1994) Cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. Nature 370, 471–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castilla J., Saá P., Hetz C., Soto C. (2005) In vitro generation of infectious scrapie prions. Cell 121, 195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atarashi R., Moore R. A., Sim V. L., Hughson A. G., Dorward D. W., Onwubiko H. A., Priola S. A., Caughey B. (2007) Ultrasensitive detection of scrapie prion protein using seeded conversion of recombinant prion protein. Nat. Methods 4, 645–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soto C., Anderes L., Suardi S., Cardone F., Castilla J., Frossard M. J., Peano S., Saa P., Limido L., Carbonatto M., Ironside J., Torres J. M., Pocchiari M., Tagliavini F. (2005) Pre-symptomatic detection of prions by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. FEBS Lett. 579, 638–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atarashi R., Satoh K., Sano K., Fuse T., Yamaguchi N., Ishibashi D., Matsubara T., Nakagaki T., Yamanaka H., Shirabe S., Yamada M., Mizusawa H., Kitamoto T., Klug G., McGlade A., Collins S. J., Nishida N. (2011) Ultrasensitive human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time quaking-induced conversion. Nat. Med. 17, 175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saborio G. P., Permanne B., Soto C. (2001) Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature 411, 810–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caughey B., Baron G. S. (2006) Prions and their partners in crime. Nature 443, 803–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deleault N. R., Lucassen R. W., Supattapone S. (2003) RNA molecules stimulate prion protein conversion. Nature 425, 717–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deleault N. R., Harris B. T., Rees J. R., Supattapone S. (2007) Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9741–9746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deleault N. R., Piro J. R., Walsh D. J., Wang F., Ma J., Geoghegan J. C., Supattapone S. (2012) Isolation of phosphatidylethanolamine as a solitary cofactor for prion formation in the absence of nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8546–8551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deleault N. R., Kascsak R., Geoghegan J. C., Supattapone S. (2010) Species-dependent differences in cofactor utilization for formation of the protease-resistant prion protein in vitro. Biochemistry 49, 3928–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lawson V. A., Lumicisi B., Welton J., Machalek D., Gouramanis K., Klemm H. M., Stewart J. D., Masters C. L., Hoke D. E., Collins S. J., Hill A. F. (2010) Glycosaminoglycan sulphation affects the seeded misfolding of a mutant prion protein. PLoS One 5, e12351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brazier M. W., Lewis V., Ciccotosto G. D., Klug G. M., Lawson V. A., Cappai R., Ironside J. W., Masters C. L., Hill A. F., White A. R., Collins S. (2006) Correlative studies support lipid peroxidation is linked to PrPres propagation as an early primary pathogenic event in prion disease. Brain Res. Bull. 68, 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Büeler H., Aguzzi A., Sailer A., Greiner R. A., Autenried P., Aguet M., Weissmann C. (1993) Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell 73, 1339–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zimmermann K., Turecek P. L., Schwarz H. P. (1999) Genotyping of the prion protein gene at codon 129. Acta Neuropathol. 97, 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kascsak R. J., Rubenstein R., Merz P. A., Tonna-DeMasi M., Fersko R., Carp R. I., Wisniewski H. M., Diringer H. (1987) Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J. Virol. 61, 3688–3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawson V. A., Vella L. J., Stewart J. D., Sharples R. A., Klemm H., Machalek D. M., Masters C. L., Cappai R., Collins S. J., Hill A. F. (2008) Mouse-adapted sporadic human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease prions propagate in cell culture. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2793–2801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. David G., Bai X. M., Van der Schueren B., Cassiman J. J., Van den Berghe H. (1992) Developmental changes in heparan sulfate expression: in situ detection with mAbs. J. Cell Biol. 119, 961–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewis V., Hill A. F., Haigh C. L., Klug G. M., Masters C. L., Lawson V. A., Collins S. J. (2009) Increased proportions of C1 truncated prion protein protect against cellular M1000 prion infection. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68, 1125–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones M., Peden A. H., Wight D., Prowse C., Macgregor I., Manson J., Turner M., Ironside J. W., Head M. W. (2008) Effects of human PrPSc type and PRNP genotype in an in vitro conversion assay. Neuroreport 19, 1783–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones M., Peden A. H., Yull H., Wight D., Bishop M. T., Prowse C. V., Turner M. L., Ironside J. W., MacGregor I. R., Head M. W. (2009) Human platelets as a substrate source for the in vitro amplification of the abnormal prion protein (PrP) associated with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Transfusion 49, 376–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Enari M., Flechsig E., Weissmann C. (2001) Scrapie prion protein accumulation by scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells abrogated by exposure to a prion protein antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9295–9299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vorberg I., Raines A., Story B., Priola S. A. (2004) Susceptibility of common fibroblast cell lines to transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agents. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cordeiro Y., Machado F., Juliano L., Juliano M. A., Brentani R. R., Foguel D., Silva J. L. (2001) DNA converts cellular prion protein into the β-sheet conformation and inhibits prion peptide aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 49400–49409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vieira T. C., Reynaldo D. P., Gomes M. P., Almeida M. S., Cordeiro Y., Silva J. L. (2011) Heparin binding by murine recombinant prion protein leads to transient aggregation and formation of RNA-resistant species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Silva J. L., Vieira T. C., Gomes M. P., Bom A. P., Lima L. M., Freitas M. S., Ishimaru D., Cordeiro Y., Foguel D. (2010) Ligand binding and hydration in protein misfolding: insights from studies of prion and p53 tumor suppressor proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 271–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. O'Brien J. S., Sampson E. L. (1965) Lipid composition of the normal human brain: gray matter, white matter, and myelin. J. Lipid Res. 6, 537–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang F., Wang X., Yuan C. G., Ma J. (2010) Generating a prion with bacterially expressed recombinant prion protein. Science 327, 1132–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lawson V. A., Collins S. J., Masters C. L., Hill A. F. (2005) Prion protein glycosylation. J. Neurochem. 93, 793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Priola S. A., Lawson V. A. (2001) Glycosylation influences cross-species formation of protease-resistant prion protein. EMBO J. 20, 6692–6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cancellotti E., Bradford B. M., Tuzi N. L., Hickey R. D., Brown D., Brown K. L., Barron R. M., Kisielewski D., Piccardo P., Manson J. C. (2010) Glycosylation of PrPC determines timing of neuroinvasion and targeting in the brain following transmissible spongiform encephalopathy infection by a peripheral route. J. Virol. 84, 3464–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tuzi N. L., Cancellotti E., Baybutt H., Blackford L., Bradford B., Plinston C., Coghill A., Hart P., Piccardo P., Barron R. M., Manson J. C. (2008) Host PrP glycosylation: a major factor determining the outcome of prion infection. PLoS Biol. 6, e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen S. G., Teplow D. B., Parchi P., Teller J. K., Gambetti P., Autilio-Gambetti L. (1995) Truncated forms of the human prion protein in normal brain and in prion diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19173–19180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jiménez-Huete A., Lievens P. M., Vidal R., Piccardo P., Ghetti B., Tagliavini F., Frangione B., Prelli F. (1998) Endogenous proteolytic cleavage of normal and disease-associated isoforms of the human prion protein in neural and non-neural tissues. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1561–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuczius T., Koch R., Keyvani K., Karch H., Grassi J., Groschup M. H. (2007) Regional and phenotype heterogeneity of cellular prion proteins in the human brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 2649–2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]