Background: Plants lack the machinery for mucin-type O-glycosylation.

Results: Transient expression of the mammalian O-glycosylation pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana resulted in the formation of sialylated mucin-type O-glycans on recombinant erythropoietin.

Conclusion: Therapeutic proteins with engineered N- and O-glycosylation can be produced in plants.

Significance: Plants are attractive hosts for the production of glycosylated recombinant proteins with defined glycan structures.

Keywords: Erythropoietin, Glycosylation, Plant, Post Translational Modification, Recombinant Protein Expression, Sialic Acid

Abstract

Proper N- and O-glycosylation of recombinant proteins is important for their biological function. Although the N-glycan processing pathway of different expression hosts has been successfully modified in the past, comparatively little attention has been paid to the generation of customized O-linked glycans. Plants are attractive hosts for engineering of O-glycosylation steps, as they contain no endogenous glycosyltransferases that perform mammalian-type Ser/Thr glycosylation and could interfere with the production of defined O-glycans. Here, we produced mucin-type O-GalNAc and core 1 O-linked glycan structures on recombinant human erythropoietin fused to an IgG heavy chain fragment (EPO-Fc) by transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Furthermore, for the generation of sialylated core 1 structures constructs encoding human polypeptide:N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2, Drosophila melanogaster core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase, human α2,3-sialyltransferase, and Mus musculus α2,6-sialyltransferase were transiently co-expressed in N. benthamiana together with EPO-Fc and the machinery for sialylation of N-glycans. The formation of significant amounts of mono- and disialylated O-linked glycans was confirmed by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Analysis of the three EPO glycopeptides carrying N-glycans revealed the presence of biantennary structures with terminal sialic acid residues. Our data demonstrate that N. benthamiana plants are amenable to engineering of the O-glycosylation pathway and can produce well defined human-type O- and N-linked glycans on recombinant therapeutics.

Introduction

Recombinant protein-based drugs are one of the fastest growing branches of the pharmaceutical industry. Consequently, there is a demand for increasing current manufacturing capacities and exploring novel expression systems that are faster, more flexible, and possibly cheaper than established hosts. During the last 10 years there have been remarkable advances in expression technology and manipulation of posttranslational modifications in plants, which makes them promising hosts for the production of proteins of interest. In fact, a carrot cell-produced recombinant human β-glucocerebrosidase for treatment of Gaucher disease is now approved for enzyme replacement therapy in humans (1, 2). Plants are versatile production platforms as they are essentially free of human pathogens and naturally lack certain glycan epitopes that are present on recombinant glycoproteins produced in non-human mammalian cell lines (3).

Many therapeutic proteins are glycosylated, and the presence or absence of distinct sugar residues can have a significant impact on protein function in vitro and in vivo. One of the best examples demonstrating the importance of distinct glycoforms for its function is the Fc region of IgG molecules (4, 5). For the glycoprotein hormone erythropoietin (EPO),2 which regulates red blood cell formation and is the standard drug for the treatment of anemia, proper glycosylation is crucial for its in vivo function (6). In particular there is a direct, positive correlation between the sialic acid content, increased half-life in the blood, and its bioactivity. Consequently, the potency of EPO can be increased by engineering of glycosylation, such as the formation of highly branched sialylated N-glycans, introduction of additional glycosylation sites, or metabolic engineering to provide more CMP-sialic acid for sialylation (7, 8). The majority of these glycosylation engineering approaches have focused on modification of N-glycan structures on EPO, whereas little attention has so far been paid to O-glycan engineering. Both urinary and recombinant human EPO contain a single O-glycosylation site at Ser-126 that is mostly decorated with a disialylated mucin-type O-glycan (9–11). The importance of O-glycan structures for EPO stability or biological function is not entirely clear (12, 13). However, it has been suggested that the sialic acid residues from the mucin-type O-glycans could also contribute to the total sialic acid content and subsequently might influence the clearance of EPO from circulation (14).

In comparison to N-glycans, the role of different glycoforms and individual sugar residues on O-linked glycans of recombinant proteins is much less understood. Dependent on the size and composition of the O-glycan, the conformation of the protein or its activity might be affected (15). The presence of O-linked structures can mask recognition sites for receptors and other interacting proteins or protect them from degradation by proteases (16). Moreover, changes in O-glycosylation are often seen in diseases (e.g. in IgA nephropathy), and specific O-glycan structures are aberrant in tumors and are, therefore, potential targets for the development of glycopeptide-based anti-cancer vaccines (17, 18). An expression system that enables the production of recombinant glycoproteins with well defined homogenous O-linked glycans would be highly desirable not only for the biopharmaceutical industry but also for structure function studies involving glycoproteins with O-glycans.

Here we describe the production of tumor-associated antigens (Tn and T antigen) and disialylated mucin-type core 1 O-glycans on recombinant EPO transiently expressed in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants. In addition, we combine N- and O-glycan modification strategies to generate a production platform equipped with a fully functional human-type N- and O-glycosylation machinery. Our data demonstrate that plants are amenable to extensive O-glycan engineering, which greatly expands the potential of plants as novel expression hosts for the production of recombinant glycoproteins with customized glycans.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Plant Binary Expression Vector

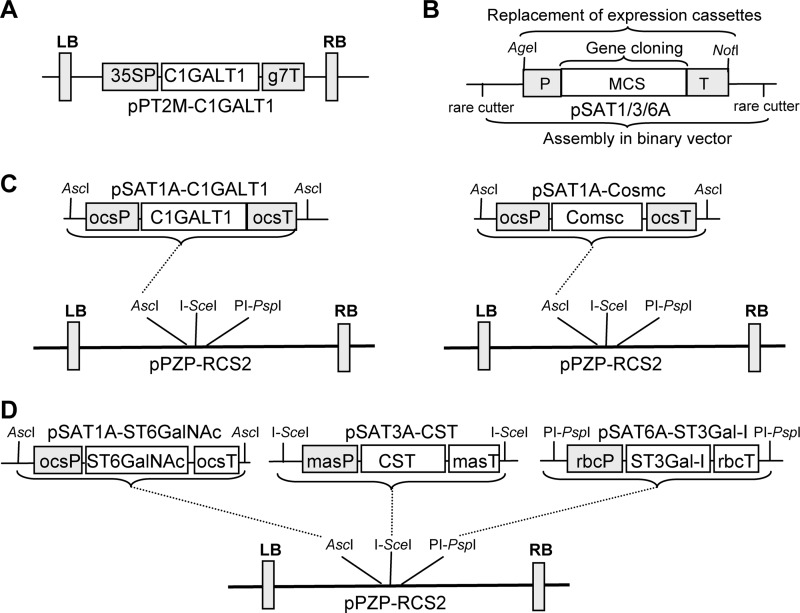

The binary vector for expression of human GalNAc-T2 (pH7WG2:GNT2) was described previously (19). Binary vectors for expression of Caenorhabditis elegans UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter (pH7WG2:GT) and Yersinia enterocolitica UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase (pH7WG2:GE) were generated by Gateway LR-reaction transfer (Invitrogen) of the appropriate gene from the pENTR/D-Topo-based shuttle vectors (19) to pH7WG2 plant expression vector (20). EPO-Fc was expressed using the magnICON viral-based expression system (21) as described previously (22). A codon-optimized open reading frame coding for human core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase (C1GALT1) was obtained from GeneArt Gene Synthesis (Invitrogen). XhoI and BamHI restriction enzyme recognition sites were incorporated at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively, to facilitate subsequent cloning into the XhoI/BamHI sites of the auxiliary vector pSAT1A (pSAT1A-C1GALT1) (23). The rare-cutting enzyme AscI was used to clone the expression cassette of pSAT1A-C1GALT1 into pPZP-RCS2 binary expression vector.

A clone (IMAGE ID: 5724507) coding for human COSMC was purchased from Source BioScience (Cambridge, UK). The open reading frame was amplified by PCR using oligos Chaperon-F1 (5′-TATACTCGAGATGCTTTCTGAAAGCAGC-3′) and Chaperon-R1 (5′-TATAAGATCTTCAGTCATTGTCAGAACC-3′), digested with XhoI/BglII, and ligated into XhoI/BamHI digested pSAT1A vector (pSAT1A-Cosmc). The rare-cutting enzyme AscI was used to transfer the expression cassette from pSAT1A-Cosmc to pPZP-RCS2. A codon-optimized clone of Drosophila melanogaster C1GALT1 was synthesized by GeneArt Gene Synthesis with flanking XbaI and BamHI restriction sites. The XbaI/BamHI fragment was cloned into the binary expression vector pPT2M (pPT2M-C1GALT1) (24). In this vector, expression is under control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. A clone (IMAGE ID: 3925036) coding for human α2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3Gal-I) was purchased from Source BioScience, amplified with oligos S3GAL1-F1 (5′-TATACTCGAGATGGTGACCCTGCGGAAG-3′)/S3GAL1-R1 (5′-TATAGGATCCTCATCTCCCCTTGAAGATC-3′), XhoI/BamHI-digested, and cloned into pSAT6A to generate vector pSAT6A-ST3Gal-I. A clone (IMAGE ID: 6844232) coding for Mus musculus α2,6-sialyltransferase (ST6GalNAc-III/IV) was purchased from Source BioScience. The corresponding open reading frame was amplified by PCR using oligos ST6GAL-F1 (5′-TATACTCGAGATGAAGGCCCCGGGCCGC-3′)/ST6GAL-R1 (5′-TATAGGATCCCTACTTGGCCCTCCAGGAC-3′), XhoI/BamHI-digested, and cloned into pSAT1A vector (pSAT1A-ST6GalNAc). To reduce the number of constructs during the agroinfiltration procedure, ST3Gal-I and ST6GalNAc-III/IV were expressed from one construct together with the Golgi CMP-sialic acid transporter (CST) (25). CST was amplified from the M. musculus cDNA clone using oligos CST-F1 (5′-TATACTCGAGATGGCTCCGGCGAGAGAAAATG-3′) and CST-R1 (5′-TATAGGATCCTCACACACCAATGATTCTCTC-3′) and cloned into XhoI/BamHI-digested pSAT3A vector (pSAT3A-CST). To obtain the construct for simultaneous expression of the three proteins, the expression cassette of pSAT1A-ST6GalNAc was removed by AscI digestion and cloned into the AscI site of pPZP-RCS2, the expression cassette from pSAT6A-ST3Gal-I was removed by digestion with the homing endonuclease PI-PspI and cloned into the PI-PspI site of pPZP-RCS2, and the CST expression cassette was inserted into the I-SceI site of pPZP-RCS2.

All binary vectors except the magnICON constructs were transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain UIA 143. All magnICON constructs were transformed into strain GV3101 pMP90. Bacterial suspensions were infiltrated at the following optical densities (OD600): magnICON constructs, 0.1; binary vectors, 0.05. In all co-expression experiments the respective bacterial suspensions were mixed 1:1 before infiltration.

Plant Material

N. benthamiana wild-type and glycoengineered ΔXTFT line (26) were grown in a growth chamber at 22 °C with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. All constructs were expressed by agroinfiltration of leaves as described in detail previously (26).

Analysis of N- and O-Linked Glycans

EPO-Fc was purified from infiltrated leaves by affinity chromatography using rProteinA-Sepharose ™ Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) as described in detail previously (22). Purified EPO-Fc was separated by SDS-PAGE, and protein bands were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-EPO (MAB2871, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or anti-human IgG (anti-Fc) (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) antibodies. The corresponding band was excised from the gel and double-digested with trypsin and endoglucosaminidase C (Glu-C) (sequencing grade, Roche Applied Science). Glycopeptide analysis was carried out by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) as described in detail previously (27, 28).

RESULTS

Strategy for Sialylated Mucin-type O-Glycan Engineering in Plants

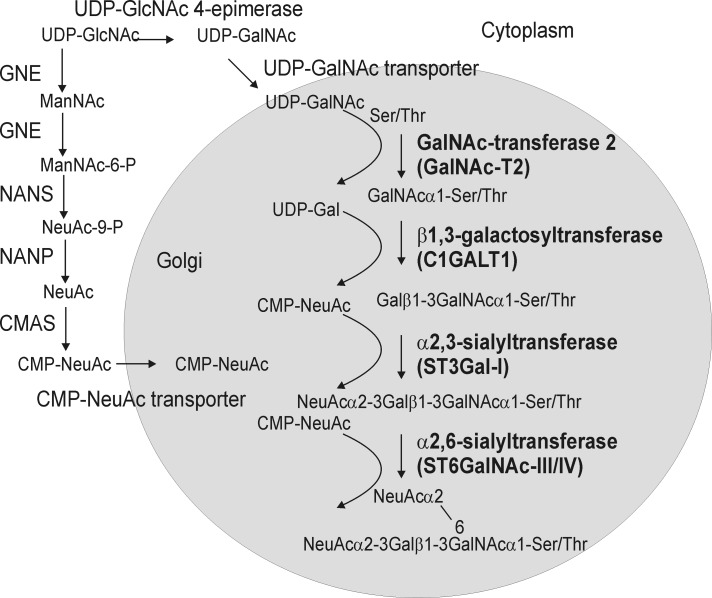

Biosynthesis of sialylated mucin-type core 1 structures in N. benthamiana requires enzymatic reactions as well as transport steps from the cytosol to the Golgi lumen. For the transfer of GalNAc residues to Ser/Thr, which is the initiation step of mucin-type O-glycosylation and presumably takes place in the Golgi apparatus, UDP-GlcNAc must be converted to UDP-GalNAc in the cytosol, and UDP-GalNAc must be transported into the Golgi lumen where it is used by a polypeptide:N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GalNAc-T) to attach GalNAc residues to specific O-glycosylation sites within a protein (Fig. 1). Constructs for expression of the corresponding proteins are available from a previous study (19), and similar constructs have been successfully used by another group to initiate O-glycan formation in plants (29).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the pathway for the formation of disialylated O-glycans in plants. UDP-GalNAc formation and CMP-NeuAc biosynthesis start from the nucleotide sugar UDP-GlcNAc. The steps for conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-NeuAc and transport of CMP-NeuAc to the Golgi have been engineered in plants previously (25, 34). The specific steps that seem absolutely required for sialylated mucin-type O-glycan biosynthesis are depicted in bold. GNE, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase; NANS, N-acetylneuraminic acid phosphate synthase; CMAS, CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase; NANP, N-acetylneuraminate-9-phosphate phosphatase. Conversion of NeuAc-9-P to NeuAc is very likely carried out by an endogenous plant enzyme.

One of the most common O-glycan extensions is the formation of the core 1 structure (T-antigen). Core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase (C1GALT1, also called core 1 or T-synthase) catalyzes the transfer of a single galactose residue from UDP-Gal to GalNAcα1-O-Ser/Thr to generate Galβ1–3GalNAcα1-O-Ser/Thr. In humans, this particular step requires the co-expression of a specific chaperone termed COSMC (30). COSMC binds to human C1GALT1 in the endoplasmic reticulum and is required for correct folding of the glycosyltransferase and subsequently for localization and activity in the Golgi. Invertebrates and plants lack COSMC homologs, and consequently, we hypothesized that human C1GALT1 expression depends on the co-expression of COSMC. Alternatively C1GALT1 from Drosophila or another invertebrate could be functional in plants without any additional chaperone.

Core 1 structures are frequently capped with sialic acid residues. This terminal modification step requires the co-expression of the respective sialyltransferases, e.g. transfer of N-acetylneuraminic acid (NeuAc) in α2,3-linkage to galactose by α2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3Gal-I) and transfer of NeuAc in α2,6-linkage to the GalNAc residue, which is catalyzed by α2,6-sialyltransferase (ST6GalNAc-III/IV) (Fig. 1). All used constructs are listed in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of newly generated vectors. A, binary vector for the expression of the Drosophila C1GALT1 is shown. B, shown are structural features of the pSAT series of auxiliary vectors (pSAT1A, pSAT3A, and pSAT6A) for the assembly of promoter-gene-terminator cassettes. Rare-cutting enzymes flanking each pSAT vector are used to transfer the expression cassettes into the expression vector pPZP-RCS2. C, shown is the outline of the cloning strategy for expression of human C1GALT1 and its chaperone COSMC. D, shown is a schematic representation of the cloning strategy for the multiple gene expression vector. The CST, ST3Gal-I, and ST6GALNAc-III/IV open reading frames were cloned into different pSAT auxiliary vectors and were then sequentially assembled in pPZP-RCS2 using specific rare-cutting enzymes. In the final constructs all three proteins are expressed under different promoter and terminator sequences. 35SP, cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; g7T, Agrobacterium gene 7 terminator; ocsP, octopine synthase promoter; ocsT, octopine synthase terminator; rbcP, rubisco small subunit promoter; rbcT, rubisco small subunit terminator; masP, manopine synthase promoter; masT, manopine synthase terminator; LB, left border sequence; RB, right border sequence.

Expression of Recombinant EPO-Fc in Plants

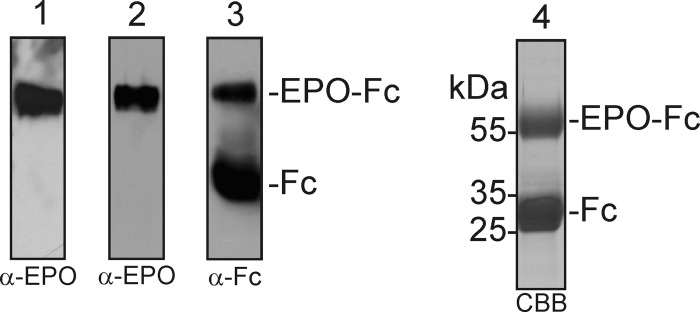

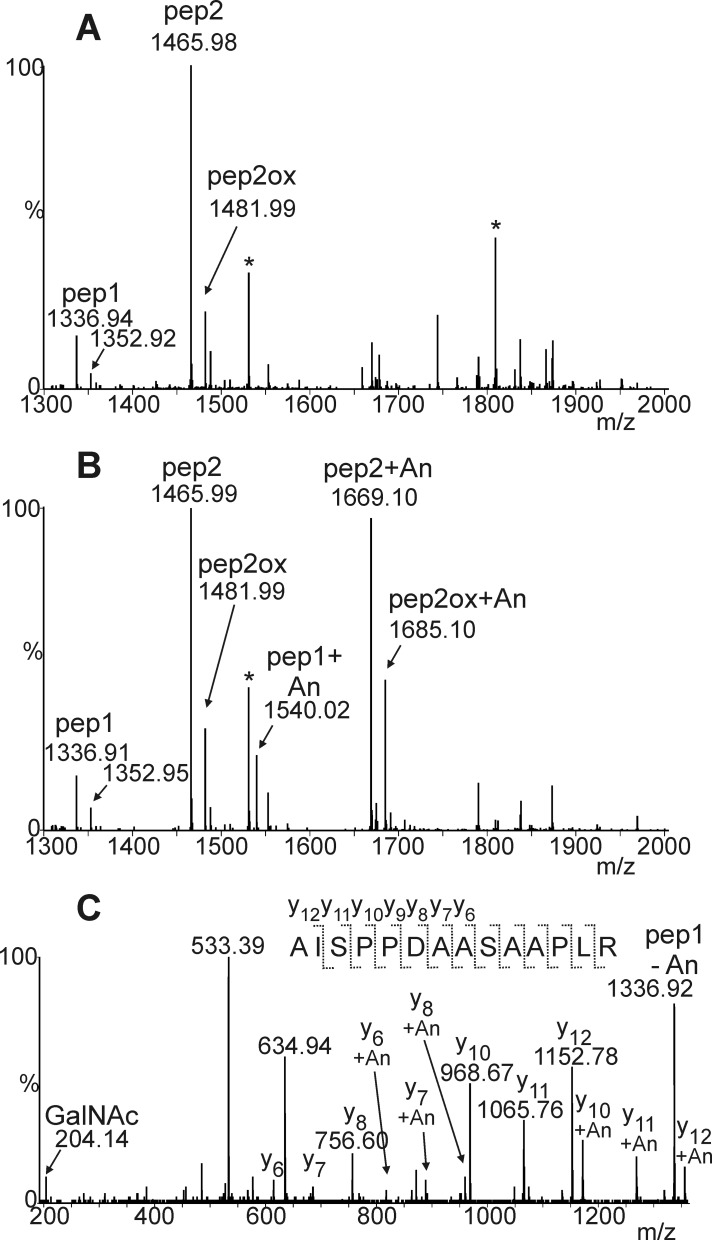

We previously showed production of human EPO fused to the Fc domain of an IgG molecule (EPO-Fc) by transient expression in the glycoengineered N. benthamiana line ΔXTFT (22). All three N-glycosylation sites of ΔXTFT-produced recombinant EPO are occupied by complex N-glycans almost completely lacking the plant-specific β1,2-xylose and core α1,3-fucose residues. In another study it was reported that this EPO-Fc fusion protein expressed in N. benthamiana using the viral-based magnICON expression system accumulated to ∼1–5 mg per kg fresh weight and was biologically active (31). Here we used the same magnICON construct for expression of EPO-Fc in ΔXTFT (Fig. 3) and purified the recombinant protein by protein A affinity chromatography. As previously reported (22, 31), a 55-kDa band corresponding to the full-length EPO-Fc as well as a smaller 30-kDa band corresponding to the molecular mass of free Fc was obtained (Fig. 3). The 55-kDa EPO-Fc was excised from the SDS-PAGE gel, and trypsin/Glu-C double-digested peptides were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS, which gave the expected peptide AISPPDAASAAPLR and the cleavage variant EAISPPDAASAAPLR (Fig. 4a). Tandem mass spectrometry of peptides confirmed the identity of the non-glycosylated peptide comprising Ser-126 in recombinant human EPO (data not shown). A smaller peak corresponding to a non-glycosylated peptide with a hydroxylated proline residue (mass shift +16 Da) was observed, indicating that one of the three proline residues that are adjacent to Ser-126 is modified by an endogenous prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Furthermore a peak indicative of a double-hydroxylated peptide occurred. Each substitution of Pro by Hyp brought about a lowering of the retention time by about 2 min. As a result, the various peptides are spread over a considerable elution time range. Because hydroxyproline residues are sites for plant-specific O-glycosylation, we looked for the presence of arabinose chains, but no signals indicating the presence of one to four arabinose residues were found.

FIGURE 3.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of EPO-Fc expressed in N. benthamiana. Total soluble protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-EPO antibodies (α-EPO) (1). Eluates from the protein A purification were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with α-EPO (2) with anti human IgG antibodies (α-Fc) (3) or by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (4). Representative images are shown.

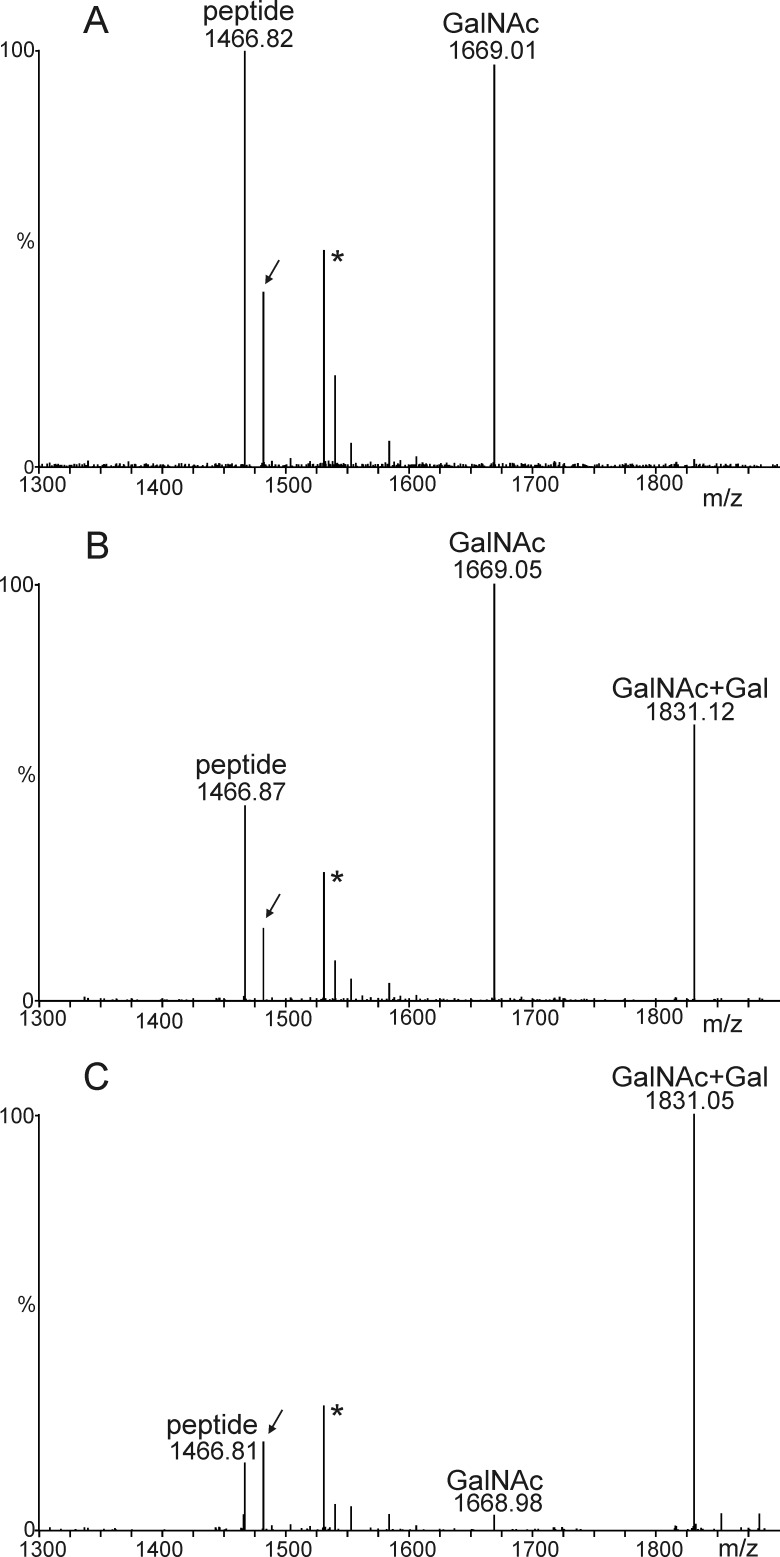

FIGURE 4.

Initiation of O-GalNAc formation on Ser-126 of recombinant plant-produced EPO-Fc. Mass spectra of trypsin and endoproteinase Glu-C double-digested EPO-Fc expressed in N. benthamiana ΔXTFT line are shown. A, shown is a spectrum of the EPO-Fc Ser-126-containing peptide(s) in the absence of any O-glycan machinery; due to partial miscleavage, two peptides containing Ser-126 are generated, pep1 (AISPPDAASAAPLR) and pep2 (EAISPPDAASAAPLR). B, shown is a spectrum of the EPO-Fc Ser-126 peptides from plants co-expressing GalNAc-T2, UPD-GlcNAc 4-epimerase, and UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter with EPO-Fc. The presence of glycosylated peptides is indicated (+An indicates the presence of GalNAc residues). The presence of peptides with hydroxyproline residues (Pro to Hyp conversion: +16 Da, e.g. pep2ox) is indicated by arrows. The glycosylated versions of this peptide as well as the double- hydroxylated peptide eluted outside of the displayed time window. Asterisks denote the presence of co-eluting peptides or contaminations. C, shown is the Y-ion series of LC-ESI-MS/MS fragmentation experiment of the O-glycosylated EPO-Fc peptide (+An indicates the presence of a single GalNAc residue).

Initiation of Mucin-type O-Glycosylation on Recombinant Plant-produced EPO-Fc

Previously it has been shown by lectin blotting that initiation of mucin-type O-glycan formation on a recombinant reporter protein expressed in N. benthamiana can be achieved by co-expression of human GalNAc-T2, a Y. enterocolitica UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase, and a C. elegans UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter (19). To investigate whether the co-expression of this O-glycosylation machinery leads to the initiation of O-GalNAc formation on recombinant EPO-Fc, we expressed all four proteins transiently in ΔXTFT. LC-ESI-MS analysis of trypsin/Glu-C digested EPO-Fc (Fig. 4b) showed a peak that corresponds to the mass of an O-glycosylated peptide. Tandem mass spectrometry of peptides confirmed the identity of the glycosylated peptide comprising Ser-126 in recombinant human EPO (Fig. 4c). These data show the successful initiation of mucin-type O-glycosylation on recombinant EPO-Fc.

Production of Core 1 Structures on Recombinant Plant-produced EPO-Fc

The next O-glycan elongation step is the transfer of a galactose residue in β1,3-linkage to produce the core 1 structure on EPO-Fc. In our first attempt we transiently expressed human C1GALT1 with human COSMC and the three constructs for O-GalNAc formation together with EPO-Fc in N. benthamiana. Analysis of trypsin/Glu-C double-digested peptides by mass spectrometry revealed the presence of a peak corresponding to a galactosylated O-GalNAc structure (Fig. 5, a and b). However, the major peak corresponded to the O-GalNAc-modified peptide, indicating that the transfer of galactose was not very efficient. Next, we chose to transiently express Drosophila C1GALT1 together with GalNAc-T2 and the UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter as well as the UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase and analyzed the glycopeptide containing Ser-126 from EPO-Fc (Fig. 5c). In contrast to human C1GalT1, expression of Drosophila C1GALT1 resulted in an almost complete conversion of O-GalNAc to Galβ1–3GalNAc. These data suggest that human C1GALT1 is not properly expressed in plants or is rapidly degraded, presumably because the C1GALT1-COSMC interaction is less efficient when expressed in a heterologous system. Drosophila C1GALT1 on the other hand was very effective in synthesis of core 1 structures on recombinant EPO-Fc.

FIGURE 5.

Generation of T-antigen (Galβ1–3GalNAc) by co-expression of C1GALT1. A, co-expression of EPO-Fc with the machinery for O-GalNAc formation is shown. B, co-expression of EPO-Fc with the machinery for O-GalNAc formation, human C1GALT1, and its specific chaperone COSMC is shown. C, co-expression of EPO-Fc with the machinery for O-GalNAc formation and Drosophila C1GALT1 is shown. The spectra show the O-glycosylated EPO-Fc Ser-126-containing peptide (117EAISPPDAASAAPLR131). The arrow points at the peptide with one hydroxyproline residue. Unrelated peaks are denoted by an asterisk.

Decoration of Core 1 Structures on Recombinant Plant-produced EPO-Fc with Sialic Acids

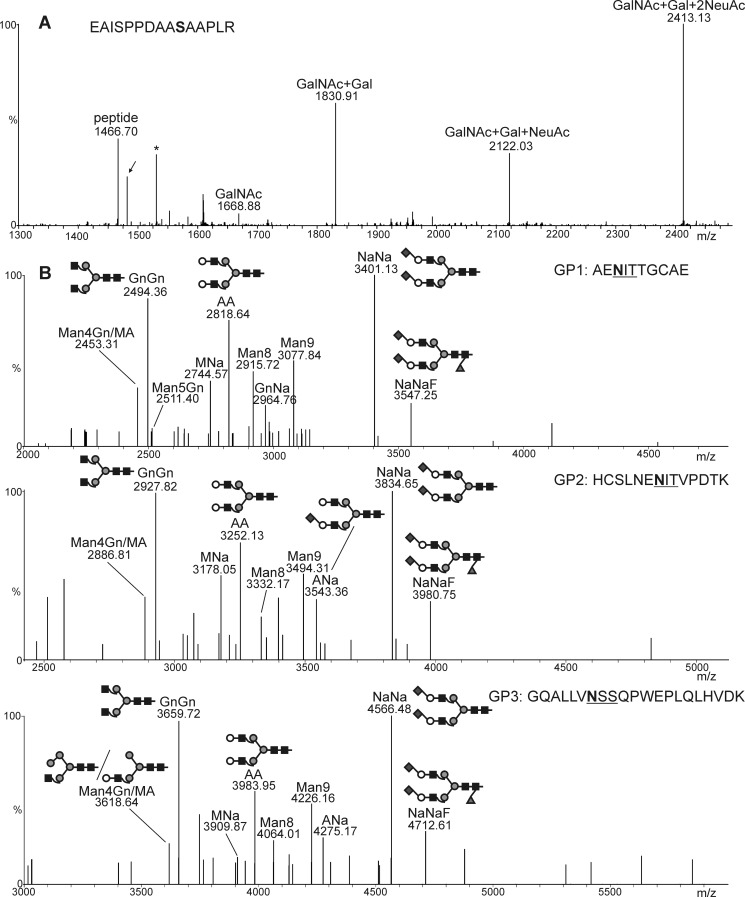

The final steps in our engineering approach were the capping of the core 1 structure by sialic acid. Co-expression of the O-glycosylation machinery for the core 1 structure formation with human ST3Gal-I, M. musculus ST6GalNAc-III/IV, and the sialylation machinery resulted in the formation of peaks corresponding to the incorporation of one and two sialic acid residues into the core 1 structure (Fig. 6a), thus showing that sialylated core 1 structures can be produced on recombinant EPO-Fc in our glycoengineered plants.

FIGURE 6.

Generation of disialylated O-glycans on EPO-Fc. A, shown are co-expression of EPO-Fc with the mammalian pathway for CMP-sialic acid synthesis, its transport to the Golgi, and the O-glycosylation machinery including UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase, UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter, GalNAc-T2, Drosophila C1GALT1, ST3Gal-I, and ST6GalNAc-III/IV. The LC-ESI-MS spectrum depicts the presence of all possible glycosylation variants up to a doubly sialylated core-1 O-glycan structure. The presence of a peptide corresponding to the hydroxylation of a single proline residue is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes the presence of a contamination. B, analysis of the three EPO-Fc peptides containing N-linked glycans is shown. N-Glycan analysis was carried out by LC-ESI-MS of tryptic/Glu-C double-digested EPO-Fc.

The requirement of heterologous expression of UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase and a UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter has been controversial (19, 29). To investigate whether these two proteins are necessary for O-glycan initiation and modification on EPO-Fc, we compared the engineered O-glycan structures in the presence and absence of Y. enterocolitica UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase and a C. elegans UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter. We found that expression of human GalNAc-T2 is sufficient for the generation of O-GalNAc on EPO-Fc (supplemental Fig. S1). Moreover, core 1 and sialylated core 1 structures were also generated in the absence of an additionally co-expressed epimerase or transporter (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that endogenous plant proteins can produce sufficient amounts of UDP-GalNAc and perform UDP-GalNAc transport into the Golgi where it is used as donor substrate by GalNAc-T2.

Structural Analysis of N-Linked Glycans on Recombinant Plant-produced EPO-Fc

Efficient N- and O-glycosylation requires sufficient pools of the nucleotide sugar UDP-GlcNAc, which serves as the precursor for conversion into UDP-GalNAc or CMP-sialic acid (Fig. 1). Furthermore, UDP-GlcNAc is also used as the donor substrate by endogenous N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases during synthesis and processing of N-glycans. In addition, introduction of the Golgi-resident mammalian glycosyltransferases and the additionally expressed Golgi transporter could disturb the organization of endogenous N-glycosylation enzymes in the Golgi and subsequently affect sialylation of EPO-Fc N-glycans. To investigate whether co-expression of the six proteins for O-glycosylation (UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase, UDP-GlcNAc/UDP-GalNAc transporter, GalNAc-T2, Drosophila C1GALT1, ST6GalNAc-III/IV and ST3Gal-I) affect the N-glycan processing on EPO-Fc, we co-expressed them together with the pathway for CMP-sialic acid biosynthesis, transport, and transfer of sialic acid to β1,4-galactosylated N-glycans (additional six proteins: UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase, N-acetylneuraminic acid phosphate synthase, CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase, CMP-NeuAc transporter, β1,4-galactosyltransferase, and α2,6-sialyltransferase) (25). In total, 12 proteins were co-expressed transiently in ΔXTFT plants together with EPO-Fc. All three glycopeptides from EPO-Fc displayed as a major peak a disialylated biantennary N-glycan structure that corresponds to NeuAc2Gal2GlcNAc2Man3GlcNAc2 (NaNa) (Fig. 6b), showing that the generation of disialylated mucin-type O-glycans does not interfere with N-glycan engineering.

To rule out the possibility of cross-talk between the two different glycosylation pathways, we analyzed whether sialylated N-glycans can be generated by the two sialyltransferases (ST3Gal-I and ST6GalNAc-III/IV) used for O-glycan modification. In the absence of α2,6-sialyltransferase, no sialylated N-glycans were generated, showing that the two mammalian O-glycan-specific sialyltransferases retained their specificity when expressed in plants (supplemental Fig. S2). In addition, the O-GalNAc structure was not modified by β1,4-galactosyltransferase and α2,6-sialyltransferase (supplemental Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

Here we report for the first time the generation of sialylated mucin-type O-glycans on a plant-produced recombinant glycoprotein intended for therapeutic use in humans. In addition to the disialyl core 1 structure, we could also very efficiently produce the T-antigen on EPO by expression of the Drosophila C1GALT1, and our data show that O-glycan modifications do not interfere with the N-glycosylation capacity of glycoengineered plants. Notably, the leaves of infiltrated plants expressing the whole O-glycosylation machinery did not display any obvious phenotype. Biomass production and expression of recombinant EPO-Fc was also unchanged, which highlights the flexibility of our N. benthamiana-based transient expression platform. However, although N. benthamiana plants are amenable to rapid scale-up and high biomass yield can be obtained within a short time period, the expression levels of EPO-Fc and protocols for downstream processing have to be optimized to make the production system commercially more attractive.

The first attempts toward formation of mammalian-like mucin-type O-glycosylation in plants were performed by expression of the machinery to transfer GalNAc residues to O-glycosylation sites of recombinant proteins expressed in N. benthamiana (19, 29). In the latter study the incorporation of GalNAc residues was confirmed by structural analysis of the corresponding glycopeptides. Several Ser/Thr residues of a reporter protein containing a MUC1 tandem repeat motif were modified by the transient co-expression of a GlcNAc 4-epimerase together with human GalNAc-T2 and GalNAc-T4 to achieve high density O-glycosylation. A similar approach was used to generate O-GalNAc modifications by stable expression of the genes in Arabidopsis thaliana (32). Here, we demonstrate that O-glycosylation initiation on EPO-Fc requires only GalNAc-T2, and we extend the mucin-type O-GalNAc structure further by transfer of galactose and decoration of the terminal positions with sialic acid. Especially the generation of sialic acid containing O-glycans is challenging because plants lack the whole machinery to produce CMP-NeuAc and related sialic acid (33, 34). Consequently, the nucleotide sugar CMP-NeuAc must be generated in the cytosol/nucleus (25) and transported to the proper Golgi compartment where it is transferred to N- and O-linked glycans.

Furthermore, because our studies were carried out in our glycoengineered ΔXTFT line (26), we could combine N- and O-glycan engineering approaches to generate a platform capable for human-type glycoform production. Similar extensive modifications of two interacting glycosylation pathways have not been reported so far in other engineered expression hosts (35–38).

The production of defined homogenous carbohydrate structures on recombinant proteins is a prerequisite for in-depth structure function analysis of glycoforms. The role of O-linked glycans is typically investigated by mutagenesis of the respective O-glycosylation sites (39) but not by analysis of the contribution of individual glycan structures. Here, in this proof-of-concept study the O-glycosylation site of EPO served as a reporter protein to show that customized biosynthesis of O-glycan structures is possible. The role of the O-linked glycan for EPO is not very well understood. In one study Ser-126 was changed to Gly and the mutated EPO protein was not properly secreted, which led to the conclusion that the O-glycan might play a role in efficient secretion of EPO (40). However, a block in O-glycan formation in a mutant CHO line did not affect the secretion of EPO or its in vitro and in vivo biological activities (12). In comparison, our plant-based production system offers greater flexibility with respect to production of defined glycoforms and may provide a useful tool to discover novel functions of O-linked glycans on recombinant EPO or other O-glycosylated proteins in the future.

In contrast to CHO cells, N. benthamiana plants contain a limited protein glycosylation repertoire and are, therefore, better amenable to glycoengineering by expression of only those mammalian proteins (e.g. α2,6-sialyltransferase) that generate the desired glycan modification. Due to the presence of the endogenous O-glycosylation machinery heterogeneity is frequently observed on recombinant proteins produced in mammalian cells. Analysis of O-glycosylation in an EPO-Fc CHO cell-based producer line (41) showed that under different growth conditions, only ∼50% of all O-glycosylation sites on EPO-Fc are occupied by glycans, and similar to our findings, mono- as well as disialylated O-glycans were detected. Consequently strategies are employed to reduce the background glycosylation and the observed glycan heterogeneity in mammalian cells (42). Apart from differences in glycosyltransferase expression and substrate specificity, the number of homogenous glycan structures might also be increased by strategies that increase the availability of nucleotide sugars like CMP-NeuAc, e.g. by avoiding feedback regulation (43) or elimination of unwanted nucleotide sugar hydrolyzing enzyme activities (44).

One potential hurdle for the broad use of plants for the manufacturing of O-glycosylated therapeutic proteins or peptides could be the presence of hydroxyproline residues close to O-glycosylation sites. These hydroxyproline residues can be further modified by the endogenous plant O-glycosylation machinery, leading to the attachment of arabinose residues or arabinogalactans. Arabinose residues close to O-glycosylation sites have been described for maize-produced IgA and for a mucin-tandem repeat containing peptide expressed in N. benthamiana (45, 46). These plant-specific glycans could cause immunogenic or allergenic reactions in humans (47). Although small amounts of hydroxyproline residues were found on recombinant EPO-Fc, we could not detect any incorporation of arabinose to adjacent hydroxyproline residues or other plant-specific O-glycosylation. These data are consistent with reports on expression of recombinant EPO in Physcomitrella patens and a mucin-tandem repeat containing protein in N. benthamiana (29, 48). Future research directions will focus on strategies to prevent hydroxyproline formation by using inhibitors for prolyl 4-hydroxylases or specific knockdown/knock-out of the corresponding enzymes (32, 49, 50).

The approach presented here is the first step toward the generation of elongated and branched O-glycans in plants and is not restricted to recombinant EPO-Fc but can very likely also be used for other glycoproteins. In the future we will extend the glycosylation repertoire of N. benthamiana further by engineering of additional O-glycosylation steps like the formation of other core structures (17) and the production of glycopeptide vaccines containing well defined O-glycan structures like T, Tn, and sialyl-Tn that are associated with cancer cells and might be used to break self-antigen tolerance when applied as a vaccine. Moreover, optimization of the expression of the different non-plant proteins and their subcellular localization will help to achieve even more homogenous N- and O-glycan structures on recombinant proteins and thus will make glycoengineered N. benthamiana an exciting new host for the production of glycoprotein pharmaceuticals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pia Gattinger, Eva Liebminger, and Christiane Veit, Department of Applied Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by a grant (to R. S.) from the Federal Ministry of Transport, Innovation, and Technology (bmvit) and Austrian Science Fund (FWF) TRP 242-B20 (to R. S.), by the PhD program “BioToP-Biomolecular Technology of Proteins” from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) Project W1224-B09 (to L. N.), and by a grant from the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) Laura Bassi Centres of Expertise project 822757 (to H. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- EPO

- erythropoietin

- Fc

- heavy chain fragment

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- ΔXTFT

- N. benthamiana glycosylation mutant deficient in β1,2-xylosyltransferase and core α1,3-fucosyltransferase

- CST

- CMP-sialic acid transporter

- Glu-C

- endoglucosaminidase C

- GalNAc-T

- N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zimran A., Brill-Almon E., Chertkoff R., Petakov M., Blanco-Favela F., Muñoz E. T., Solorio-Meza S. E., Amato D., Duran G., Giona F., Heitner R., Rosenbaum H., Giraldo P., Mehta A., Park G., Phillips M., Elstein D., Altarescu G., Szleifer M., Hashmueli S., Aviezer D. (2011) Pivotal trial with plant cell-expressed recombinant glucocerebrosidase, taliglucerase alfa, a novel enzyme replacement therapy for Gaucher disease. Blood 118, 5767–5773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maxmen A. (2012) Drug-making plant blooms. Nature 485, 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ghaderi D., Zhang M., Hurtado-Ziola N., Varki A. (2012) Production platforms for biotherapeutic glycoproteins. Occurrence, impact, and challenges of non-human sialylation. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 28, 147–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jefferis R. (2012) Isotype and glycoform selection for antibody therapeutics. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 526, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loos A., Steinkellner H. (2012) IgG-Fc glycoengineering in non-mammalian expression hosts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 526, 167–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fukuda M. N., Sasaki H., Lopez L., Fukuda M. (1989) Survival of recombinant erythropoietin in the circulation: the role of carbohydrates. Blood 73, 84–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Egrie J. C., Dwyer E., Browne J. K., Hitz A., Lykos M. A. (2003) Darbepoetin alfa has a longer circulating half-life and greater in vivo potency than recombinant human erythropoietin. Exp. Hematol. 31, 290–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Son Y. D., Jeong Y. T., Park S. Y., Kim J. H. (2011) Enhanced sialylation of recombinant human erythropoietin in Chinese hamster ovary cells by combinatorial engineering of selected genes. Glycobiology 21, 1019–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sasaki H., Bothner B., Dell A., Fukuda M. (1987) Carbohydrate structure of erythropoietin expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells by a human erythropoietin cDNA. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 12059–12076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsuda E., Kawanishi G., Ueda M., Masuda S., Sasaki R. (1990) The role of carbohydrate in recombinant human erythropoietin. Eur. J. Biochem. 188, 405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hokke C. H., Bergwerff A. A., Van Dedem G. W., Kamerling J. P., Vliegenthart J. F. (1995) Structural analysis of the sialylated N- and O-linked carbohydrate chains of recombinant human erythropoietin expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Sialylation patterns and branch location of dimeric N-acetyllactosamine units. Eur. J. Biochem. 228, 981–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wasley L. C., Timony G., Murtha P., Stoudemire J., Dorner A. J., Caro J., Krieger M., Kaufman R. J. (1991) The importance of N- and O-linked oligosaccharides for the biosynthesis and in vitro and in vivo biologic activities of erythropoietin. Blood 77, 2624–2632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delorme E., Lorenzini T., Giffin J., Martin F., Jacobsen F., Boone T., Elliott S. (1992) Role of glycosylation on the secretion and biological activity of erythropoietin. Biochemistry 31, 9871–9876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elliott S., Egrie J., Browne J., Lorenzini T., Busse L., Rogers N., Ponting I. (2004) Control of rHuEPO biological activity. The role of carbohydrate. Exp. Hematol. 32, 1146–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kodama S., Tsujimoto M., Tsuruoka N., Sugo T., Endo T., Kobata A. (1993) Role of sugar chains in the in vitro activity of recombinant human interleukin 5. Eur. J. Biochem. 211, 903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mattu T. S., Pleass R. J., Willis A. C., Kilian M., Wormald M. R., Lellouch A. C., Rudd P. M., Woof J. M., Dwek R. A. (1998) The glycosylation and structure of human serum IgA1, Fab, and Fc regions and the role of N-glycosylation on Fc alpha receptor interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2260–2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tarp M. A., Clausen H. (2008) Mucin-type O-glycosylation and its potential use in drug and vaccine development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1780, 546–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ju T., Otto V. I., Cummings R. D. (2011) The Tn antigen-structural simplicity and biological complexity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 1770–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daskalova S. M., Radder J. E., Cichacz Z. A., Olsen S. H., Tsaprailis G., Mason H., Lopez L. C. (2010) Engineering of N. benthamiana L. plants for production of N-acetylgalactosamine-glycosylated proteins toward development of a plant-based platform for production of protein therapeutics with mucin-type O-glycosylation. BMC Biotechnol. 10, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karimi M., Inzé D., Depicker A. (2002) GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marillonnet S., Thoeringer C., Kandzia R., Klimyuk V., Gleba Y. (2005) Systemic Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transfection of viral replicons for efficient transient expression in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 718–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castilho A., Gattinger P., Grass J., Jez J., Pabst M., Altmann F., Gorfer M., Strasser R., Steinkellner H. (2011) N-Glycosylation engineering of plants for the biosynthesis of glycoproteins with bisected and branched complex N-glycans. Glycobiology 21, 813–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung S. M., Frankman E. L., Tzfira T. (2005) A versatile vector system for multiple gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 357–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strasser R., Bondili J. S., Schoberer J., Svoboda B., Liebminger E., Glössl J., Altmann F., Steinkellner H., Mach L. (2007) Enzymatic properties and subcellular localization of Arabidopsis β-N-acetylhexosaminidases. Plant Physiol. 145, 5–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Castilho A., Strasser R., Stadlmann J., Grass J., Jez J., Gattinger P., Kunert R., Quendler H., Pabst M., Leonard R., Altmann F., Steinkellner H. (2010) In planta protein sialylation through overexpression of the respective mammalian pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15923–15930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strasser R., Stadlmann J., Schähs M., Stiegler G., Quendler H., Mach L., Glössl J., Weterings K., Pabst M., Steinkellner H. (2008) Generation of glyco-engineered Nicotiana benthamiana for the production of monoclonal antibodies with a homogeneous human-like N-glycan structure. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6, 392–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stadlmann J., Pabst M., Kolarich D., Kunert R., Altmann F. (2008) Analysis of immunoglobulin glycosylation by LC-ESI-MS of glycopeptides and oligosaccharides. Proteomics 8, 2858–2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kolarich D., Jensen P. H., Altmann F., Packer N. H. (2012) Determination of site-specific glycan heterogeneity on glycoproteins. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1285–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Z., Drew D. P., Jørgensen B., Mandel U., Bach S. S., Ulvskov P., Levery S. B., Bennett E. P., Clausen H., Petersen B. L. (2012) Engineering mammalian mucin-type O-glycosylation in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11911–11923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ju T., Cummings R. D. (2002) A unique molecular chaperone Cosmc required for activity of the mammalian core 1 β3-galactosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16613–16618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nagels B., Van Damme E. J., Callewaert N., Zabeau L., Tavernier J., Delanghe J. R., Boets A., Castilho A., Weterings K. (2012) Biologically active, magnICON®-expressed EPO-Fc from stably transformed Nicotiana benthamiana plants presenting tetra-antennary N-glycan structures. J. Biotechnol. 160, 242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang Z., Bennett E. P., Jørgensen B., Drew D. P., Arigi E., Mandel U., Ulvskov P., Levery S. B., Clausen H., Petersen B. L. (2012) Toward stable genetic engineering of human O-glycosylation in plants. Plant Physiol. 160, 450–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zeleny R., Kolarich D., Strasser R., Altmann F. (2006) Sialic acid concentrations in plants are in the range of inadvertent contamination. Planta 224, 222–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Castilho A., Pabst M., Leonard R., Veit C., Altmann F., Mach L., Glössl J., Strasser R., Steinkellner H. (2008) Construction of a functional CMP-sialic acid biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 331–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Amano K., Chiba Y., Kasahara Y., Kato Y., Kaneko M. K., Kuno A., Ito H., Kobayashi K., Hirabayashi J., Jigami Y., Narimatsu H. (2008) Engineering of mucin-type human glycoproteins in yeast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3232–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hamilton S. R., Davidson R. C., Sethuraman N., Nett J. H., Jiang Y., Rios S., Bobrowicz P., Stadheim T. A., Li H., Choi B. K., Hopkins D., Wischnewski H., Roser J., Mitchell T., Strawbridge R. R., Hoopes J., Wildt S., Gerngross T. U. (2006) Humanization of yeast to produce complex terminally sialylated glycoproteins. Science 313, 1441–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harrison R. L., Jarvis D. L. (2006) Protein N-glycosylation in the baculovirus-insect cell expression system and engineering of insect cells to produce “mammalianized” recombinant glycoproteins. Adv. Virus Res. 68, 159–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacobs P. P., Geysens S., Vervecken W., Contreras R., Callewaert N. (2009) Engineering complex-type N-glycosylation in Pichia pastoris using GlycoSwitch technology. Nat. Protoc. 4, 58–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Badirou I., Kurdi M., Legendre P., Rayes J., Bryckaert M., Casari C., Lenting P. J., Christophe O. D., Denis C. V. (2012) In vivo analysis of the role of O-glycosylations of von Willebrand factor. PLoS One 7, e37508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dubé S., Fisher J. W., Powell J. S. (1988) Glycosylation at specific sites of erythropoietin is essential for biosynthesis, secretion, and biological function. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17516–17521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taschwer M., Hackl M., Hernández Bort J. A., Leitner C., Kumar N., Puc U., Grass J., Papst M., Kunert R., Altmann F., Borth N. (2012) Growth, productivity and protein glycosylation in a CHO EpoFc producer cell line adapted to glutamine-free growth. J. Biotechnol. 157, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Steentoft C., Vakhrushev S. Y., Vester-Christensen M. B., Schjoldager K. T., Kong Y., Bennett E. P., Mandel U., Wandall H., Levery S. B., Clausen H. (2011) Mining the O-glycoproteome using zinc-finger nuclease-glycoengineered SimpleCell lines. Nat. Methods 8, 977–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bork K., Reutter W., Weidemann W., Horstkorte R. (2007) Enhanced sialylation of EPO by overexpression of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManAc kinase containing a sialuria mutation in CHO cells. FEBS Lett. 581, 4195–4198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van Dijk W., Lasthuis A. M., Trippelvitz L. A., Muilerman H. G. (1983) Increased glycosylation capacity in regenerating rat liver is paralleled by decreased activities of CMP-N-acetylneuraminate hydrolase and UDP-galactose pyrophosphatase. Biochem. J. 214, 1003–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karnoup A. S., Turkelson V., Anderson W. H. (2005) O-Linked glycosylation in maize-expressed human IgA1. Glycobiology 15, 965–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pinkhasov J., Alvarez M. L., Rigano M. M., Piensook K., Larios D., Pabst M., Grass J., Mukherjee P., Gendler S. J., Walmsley A. M., Mason H. S. (2011) Recombinant plant-expressed tumor-associated MUC1 peptide is immunogenic and capable of breaking tolerance in MUC1.Tg mice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 991–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leonard R., Petersen B. O., Himly M., Kaar W., Wopfner N., Kolarich D., van Ree R., Ebner C., Duus J. Ø, Ferreira F., Altmann F. (2005) Two novel types of O-glycans on the mugwort pollen allergen Art v 1 and their role in antibody binding. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7932–7940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weise A., Altmann F., Rodriguez-Franco M., Sjoberg E. R., Bäumer W., Launhardt H., Kietzmann M., Gorr G. (2007) High level expression of secreted complex glycosylated recombinant human erythropoietin in the Physcomitrella Delta-fuc-t Delta-xyl-t mutant. Plant Biotechnol. J. 5, 389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Velasquez S. M., Ricardi M. M., Dorosz J. G., Fernandez P. V., Nadra A. D., Pol-Fachin L., Egelund J., Gille S., Harholt J., Ciancia M., Verli H., Pauly M., Bacic A., Olsen C. E., Ulvskov P., Petersen B. L., Somerville C., Iusem N. D., Estevez J. M. (2011) O-Glycosylated cell wall proteins are essential in root hair growth. Science 332, 1401–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moriguchi R., Matsuoka C., Suyama A., Matsuoka K. (2011) Reduction of plant-specific arabinogalactan-type O-glycosylation by treating tobacco plants with ferrous chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75, 994–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]