Background: Coordinated gene transcription is essential to zinc homeostasis.

Results: The human ZTRE binds a zinc-responsive transcriptional regulator and is in genes with roles in zinc-related functions.

Conclusion: The cell orchestrates coordinated gene expression through the ZTRE to achieve zinc homeostasis.

Significance: Uncovering mechanisms that underlie gene responses to fluctuating zinc supply is essential to understanding zinc homeostasis.

Keywords: Metal Homeostasis, Metals, Transcription, Transporters, Zinc, CBDW, SLC30

Abstract

Many genes with crucial roles in zinc homeostasis in mammals respond to fluctuating zinc supply through unknown mechanisms, and uncovering these mechanisms is essential to understanding the process at cellular and systemic levels. We detected zinc-dependent binding of a zinc-induced protein to a specific sequence, the zinc transcriptional regulatory element (ZTRE), in the SLC30A5 (zinc transporter ZnT5) promoter and showed that substitution of the ZTRE abrogated the repression of a reporter gene in response to zinc. We identified the ZTRE in other genes, including (through an unbiased search) the CBWD genes and (through targeted analysis) in multiple members of the SLC30 family, including SLC30A10, which is repressed by zinc. The function of the CBWD genes is currently unknown, but roles for homologs in metal homeostasis are being uncovered in bacteria. We demonstrated that CBWD genes are repressed by zinc and that substitution of the ZTRE in SLC30A10 and CBWD promoter-reporter constructs abrogates this response. Other metals did not affect expression of the transcriptional regulator, binding to the ZTRE or promoter-driven reporter gene expression. These findings provide the basis for elucidating how regulation of a network of genes through this novel mechanism contributes to zinc homeostasis and how the cell orchestrates this response.

Introduction

Genome analysis indicates that between 3 and 10% of all human genes may code for proteins that bind zinc (1). Zinc is redox-stable and forms polyhedral coordination complexes with a variety of ligands, notably histidine and cysteine. These properties render zinc a unique component of cellular proteins, where it may play a structural role, typified by the zinc finger domains of DNA-binding proteins, such as transcription factors, or contribute to enzyme catalysis. All six major enzyme classes include zinc-containing proteins. These diverse and prevalent roles of zinc in biology highlight the importance of mechanisms to maintain zinc homeostasis, at both the cellular and whole organism levels. Cellular zinc homeostasis (and whole-body zinc homeostasis in mammals) is maintained through mechanisms that include regulating the expression of genes, such as those encoding transporters responsible for the flux of zinc across cell membranes and genes encoding the intracellular zinc-binding protein metallothionein.

Key transcription factors that orchestrate the coordinated regulation of sets of genes as required to maintain zinc homeostasis (e.g. in the context of variation in zinc availability) have been identified in bacteria, yeast, and higher metazoans. Bacterial zinc-responsive transcription factors have been discovered within the ArsR-SmtB family of transcriptional derepressors (reviewed in Refs. 2 and 3), the MerR family of transcriptional activators (reviewed in Ref. 3), and the Fur family of transcriptional repressors (reviewed in Ref. 3). In Escherichia coli, the Mer family factor ZntR activates expression of a zinc exporter of the P1-type ATPase family (4), and the zinc-bound form of the Fur family transcription factor Zur represses transcription of a zinc importer of the ABC-type ATPase family (5). The central player in zinc homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the transcription factor Zap1, is induced under conditions of zinc deficiency and induces gene activation upon binding to an 11-bp zinc-responsive element (6) in the promoter regions of many genes (7), including the high affinity zinc uptake transporter ZRT1 (8) and the vacuolar zinc exporter ZRT3 (9). In the case of zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenases, Zap1-mediated transcriptional repression under conditions of zinc limitation is achieved through induction of an intergenic transcript that displaces a transcriptional activator (10) and, for the uptake transporter ZRT2, by binding to a non-consensus zinc-responsive element at a transcriptional start site (11). Transcriptional control of the expression of proteins, including zinc transporters, appears to play a major role in zinc homeostasis in plants (reviewed in Refs. 12 and 13), and Arabidopsis transcription factors essential in determining the appropriate response to zinc deficiency, with orthologs in other plant species, were identified recently (14).

In higher animals, the increased transcription of genes in response to higher levels of zinc availability can be mediated through binding of the transcription factor MFT1 (metal response element (MRE)3-binding transcription factor 1) to copies of the MRE in the promoter region. Mouse metallothoinein-1 and -2 genes (Mt1 and Mt2) and the gene for the zinc transporter ZnT1 (Slc30a1), responsible for the efflux of zinc across the plasma membrane, are up-regulated transcriptionally through this mechanism (15, 16). Like yeast Zap1, MTF1 can also act in a repressive role. In mice, the zinc transporter Zip10 (Slc39A10 gene) is repressed at the transcriptional level by MTF1 binding to an MRE downstream of the transcription start site (17), and MREs clustered in an intronic region of the zebrafish slc39a10 gene mediate transcriptional repression from one of two oppositely regulated alternative promoters (18). Repression of the human Selh gene in response to zinc is also mediated through MTF1 (19). Speculatively, these contrasting effects of MTF1 may involve the formation of co-activator complexes with different accessory proteins. MTF1-mediated activation at the Mt1 promoter was shown to require MTF1 in a complex with the transcription factor Sp1 and the histone acetyltransferase p300/CBP and was reduced by siRNA knockdown of p300/CBP. In contrast, p300/CBP knockdown did not affect MTF1-mediated activation of the mouse Slc30a1 (ZnT1) gene (20), demonstrating the principle that MTF1 can work in partnership with different protein factors in transcriptional complexes. However, mutation of the consensus MRE sequence in a zinc-repressed promoter-reporter construct based on the upstream region of the gene SLC30A5, coding for the human zinc transporter ZnT5, failed to abolish zinc-induced transcriptional repression in transfected human intestinal Caco-2 cells (21), indicating a mechanism of zinc-responsive transcriptional regulation independent of MTF1. KLF4 (Krüppel-like factor 4) appears to have a role in regulation of the zinc transporter Zip4 (gene Slc39a4) in mouse intestine, as indicated by observations including zinc-sensitive binding of KLF4 to a region of the promoter in vitro, the requirement for a KLF4 binding sequence in a Zip4 promoter-reporter construct for effects of zinc on reporter gene expression, and curtailment of Zip4 induction by zinc limitation in a mouse intestinal cell line by KLF4 knockdown (22). We detected no potential binding sites for KLF4 in the SLC30A5 promoter using Genomatix software (23), as used initially to reveal the potential for regulation of Zip4 by KLF4 in the aforementioned study. Therefore, description of the processes responsible for zinc-regulated transcription to maintain zinc homeostasis in higher animals remains incomplete.

ZnT5 exists as two major splice variants. Variant A is localized to the Golgi apparatus (21, 24), where it appears to be involved in the delivery of zinc to enzymes entering the secretory pathway (25, 26). Expression of variant B at the plasma membrane in intestinal cells (21, 27) (as well as expression in the ER in various cell lines (28)) and evidence for bidirectional function (29) indicate possible roles in systemic zinc homeostasis through uptake from and efflux into the intestinal lumen. Reduced expression in human intestinal mucosa in response to a daily zinc supplement (30) is consistent with such a role, and effects of dietary zinc on expression in mouse placenta may reflect a similar function with respect to maintenance of fetal zinc homeostasis (31).

We describe here identification of the binding site in the SLC30A5 promoter responsible for zinc-induced transcriptional repression, which we name the zinc transcriptional regulatory element (ZTRE), to which a protein factor whose expression is increased under conditions of increased zinc availability binds in a zinc-dependent manner. This work led us to discover the presence of the same regulatory element in the human SLC30A10 promoter and also in the CBWD genes, which code for the mammalian homologs of a family of proteins for which roles in metal homeostasis in bacteria and multiple eukaryotic phyla are being uncovered. We thus present the first direct evidence for a transcriptional regulatory process independent of MTF1 that operates in mammalian cells to repress transcription of multiple genes with diverse functions in response to increased zinc availability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs

Generation of the SLC30A5 promoter-reporter construct (pBlueSLC30A5prom), including the region of the gene −950 to +50 relative to the start of transcription in the plasmid pBlue-TOPO (Invitrogen), was described previously (21). Regions upstream of and including a region of the 5′-UTR of the human CBWD1 and SLC30A10 genes (−1073 to +99 and −680 to +262 relative to the start of transcription, respectively) were generated from human (Caco-2) genomic DNA by PCR. The CMV promoter sequence was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pcDNA3.1 (Clontech). ZTRE insertions were added to the CMV promoter sequence in pcDNA3.1 using a PCR-based strategy based on amplification from a pair of primers incorporating the required insertions as a complementary overlap at the 5′-ends to generate a linear product corresponding to the full-length plasmid (plus ZTRE insertions). The (methylated) template was then digested using the methylation-dependent restriction endonuclease DpnI (Fermentas Life Sciences), and then the product was circularized using T4 DNA ligase (Promega) before transformation into E. coli for plasmid purification. The CMV promoter plus ZTRE inserts was then amplified by PCR from this construct. Products were subcloned into the plasmid pBlue-TOPO to generate plasmids pBlueCBWDprom, pBlueSLC30A10prom, pBlueCMVprom, and pBlueCMVpromMUT, respectively. The insert in each construct was sequenced to confirm fidelity with the corresponding sequence in the human genome and to confirm the addition of the ZTREs to pBlueCMVpromMUT. A PCR-based strategy was used to introduce substitutions into the ZTRE sequence in pBlueSLC30A5prom, pBlueCBWDprom, and pBlueSLC30A10prom. Each promoter region was amplified from genomic (Caco-2) DNA (for SLC30A10) or from the corresponding wild-type promoter-reporter construct (for pBlueSLC30A5prom and pBlueCBWD1prom) as two sections that overlapped in the region including the ZTRE. The reverse primer used to generate the 5′-section of the product and the forward primer used to generate the 3′-section of the product included the substituted sequence. After purification (QIAquick gel extraction kit, Qiagen), the products of these reactions were diluted 1:10 and used together as template for a third PCR, using only the outermost primers (0.5 μm each) to generate the region of promoter sequence with the ZTRE substituted. PCRs contained HotStart Taq Mastermix (Qiagen) or (for the reaction to add ZTREs to the CMV promoter in pcDNA3.1) the Expand Long Template PCR System (plus manufacturer's buffer) (Roche Applied Science) and each primer at 0.5 μm. All primer sequences and thermal cycling parameters are listed in supplemental Table S1. Products were subcloned into pBlue-TOPO (to generate pBlueSLC30A5promMUT, pBlueCBWD1promMUT, and pBlueSLC30A10promMUT) and sequenced to confirm introduction of the required substitution and fidelity of the rest of the sequence. A plasmid construct for expression of human CBWD3 with a C-terminal Myc/FLAG epitope tag (pCMV6Entry-CBWD3) was purchased from Origene. For transfection of Caco-2 cells, all plasmids were purified from transformed cultures of E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) using the Endofree Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Treatment with Metals

Caco-2 and CHO cells, obtained from ATCC, were grown on plastic and maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in air in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) containing Glutamax plus 4.5 g/liter glucose, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 60 μg/ml gentamycin (all from Sigma). Cells were propagated by reseeding after removal of the adherent monolayer and cell separation by digestion with trypsin, as described previously (27). For transfection, cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells/well and transfected 24 h later using Genejamer reagent (Stratagene), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and using 2 μg of plasmid construct and 4 μl of transfection reagent per well, as described previously (21). Treatment with metals was either 24 h post-transfection or, for non-transfected cells, 72 h after seeding (when cells were confluent), as reported previously (21). Metals were added to serum-free culture medium from 1000× stock solutions (ZnSO4, ZnCl2, CuSO4, CoCl2, MgCl2, or NiCl2), and cells were incubated in this medium for 24 h.

Reporter Gene Assay

Cell lysates were prepared by the addition of 250 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 2.5 mm EDTA and then freezing at −20 °C for 30 min and thawing to room temperature before scraping cells off of the plastic and centrifuging the mixture to remove debris. The activity of β-galactosidase was measured as absorbance at 560 nm due to release of chlorophenol red from the substrate chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside, as described previously (21). Measurements were expressed relative to protein concentration of the lysate, measured using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad) against standards of BSA.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

An infrared dye (IRD)-labeled probe corresponding to the SLC30A5 promoter (−156 to +46 relative to the transcription start site) was generated from the plasmid pBlueSLC30A5prom in a PCR (HotStart Taq Mastermix, Qiagen) using thermal cycling parameters and primers (0.5 μm each) with an attached 5′-IRD molecule (Eurofins MWG Operon) as specified in supplemental Table S1. Double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide competitors were prepared from single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (Eurofins MWG Operon), listed in supplemental Table S2, by heating a 100 μm concentration of each oligonucleotide in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mm NaCl, 50 mm EDTA (final volume of 40 μl) at 96 °C for 10 min in a heating block that was then allowed to return to room temperature, to achieve slow cooling of the mixture and annealing of the complementary oligonucleotides. An IRD-labeled oligonucleotide probe including the Oct1 binding sequence was prepared in the same way from oligonucleotides labeled at the 5′-end with IRD. To prepare nuclear extracts, cells were scraped off the plastic into ice-cold PBS and centrifuged at 4 °C at 1500 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of cold lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm DTT, 25% glycerol, 0.1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)) and incubated on ice for 15 min. Cells were centrifuged at 4 °C at 3000 × g for 5 min, supernatant fluid was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of nuclear extract buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 400 mm KCl, 0.5 mm DTT, 25% glycerol, 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)). The reaction was incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 4 °C at 15,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant fluid was collected and stored at −80 °C. All reagents used in the binding reaction were purchased from LiCor Biosciences as part of the Odyssey Infrared EMSA kit. The binding reaction (total volume of 20 μl) consisted of 14 μl of ultrapure water, 2 μl of 10× Binding Buffer, 2 μl of 25 mm DTT plus 2.5% Tween 20, 1 μl of 1 μg/μl poly(dI-dC), 1 μl of 50 nm IRD end-labeled probe, and 5 μg of nuclear protein extract. Oligonucleotide competitors were included at a 200× molar excess. The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 20–30 min in the dark, and then 2 μl of 10× Orange Loading Dye was added, and the reaction was loaded onto a Criterion precast non-denaturing gel (5% Tris-HCl, 15% polyacrylamide; Bio-Rad). Before loading, the gel was prerun at 80 V in 0.5% TBE buffer. Electrophoresis was at 100 V for 90 min, and the image was captured using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from Caco-2 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and integrity was confirmed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. RNA was treated with DNase (Roche Applied Science; according to the manufacturer's instructions), and then first-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using Superscript III RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers (Promega), following the manufacturer's instructions. Relative levels of CBWD and GAPDH mRNA were measured using the Roche Lightcycler 480 and SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche Applied Science) with 20-μl reactions set up in a 96-well format containing 0.5 μm each primer, as listed in supplemental Table S1 and 1 μl of a 4-fold dilution of the reverse transcription reaction. Ct values were converted to the equivalent dilution of reverse transcription reaction as determined from a standard curve plotted from serial 2-fold dilutions.

RT-PCR (End Point)

First strand cDNA synthesis from RNA provided as the FirstChoice Human Total RNA Survey Panel (Ambion) was as above. End point PCR was carried out using HotStart Taq Mastermix (Qiagen) with primers (0.5 μm each) and thermal cycling parameters as specified in supplemental Table S1. Products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis (2% in TBE, stained with ethidium bromide).

Western Blotting

Total soluble protein from CHO cells was prepared by scraping cells into ice-cold PBS containing 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) and then collecting by centrifugation and resuspending in 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, and 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Protein concentration was determined against BSA standards using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated according to molecular weight by SDS-PAGE using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred by semidry blotting onto PVDF membrane (Amersham Biosciences Hybond-P, GE Healthcare). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C in blocking buffer (5% milk powder and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 in 1× PBS), and then primary antibody (mouse anti-FLAG monoclonal (F1804, Sigma)) was applied in blocking buffer at a dilution of 1:2000 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing membranes in 0.05% Tween in 1× PBS, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate (A2554, Sigma)) was applied at a dilution of 1:20,000 in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were developed after washing in 0.05% Tween in 1× PBS using Amersham Biosciences ECL reagent (GE Healthcare), and signals were captured on autoradiographic film.

RESULTS

Discovery That a Zinc-induced Nuclear Protein Binds to the Zinc-regulated SLC30A5 Promoter

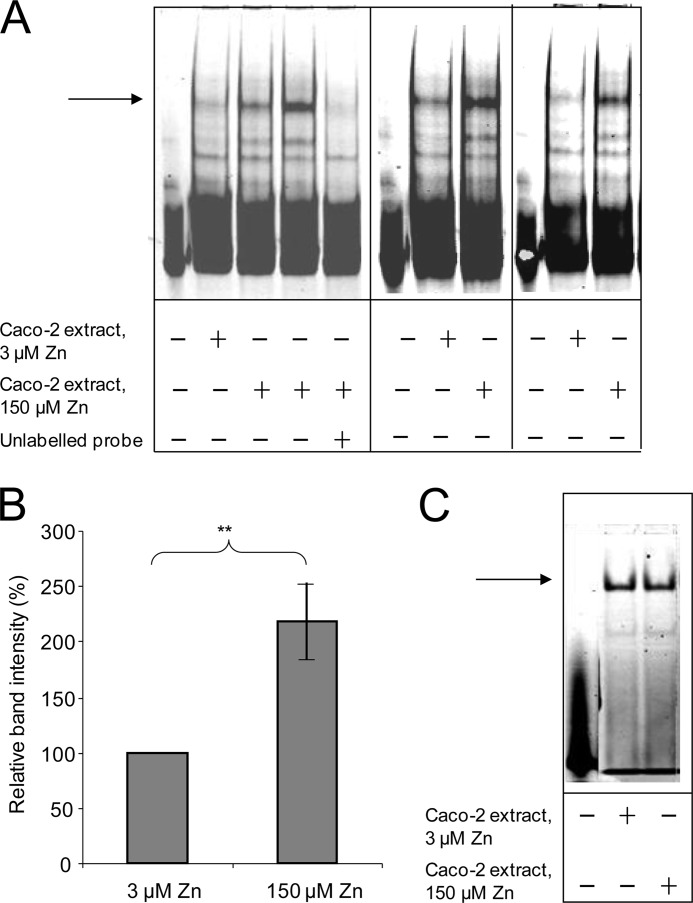

We demonstrated previously that transcriptional repression of the SLC30A5 promoter in response to 100 or 150 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc was retained in a β-galactosidase reporter construct including bases −154 to +50 relative to the end of the 5′-UTR in the cDNA sequence NM_022902 (21). We used EMSAs to investigate the binding to this promoter sequence of protein factors from extracts of Caco-2 cells cultured for 24 h at 3 or 150 μm extracellular zinc. The SLC30A5 promoter region (−156 to +46, relative to the transcription start site) was generated by PCR to incorporate an IRD label by the use of IRD-labeled primers and was electrophoresed through native 5% polyacrylamide gels in the presence or absence of the Caco-2 protein extracts. Bands representing probe whose mobility through the gel was retarded by the presence of the protein extract were observed upon IRD excitation (Fig. 1A). The predominant band was clearly of greater intensity when the probe was incubated with extract prepared from Caco-2 cells grown at 150 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc. This band was not visible when an excess of unlabeled probe was included in the binding reaction. Together these observations demonstrate specific binding to the probe of a protein factor more abundant in the nucleus of Caco-2 cells at 150 μm extracellular zinc than at 3 μm extracellular zinc. Densitometric quantification of nine independent analyses indicated an increase in band intensity of 2.2-fold (p < 0.01) at 150 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc (Fig. 1B). We excluded the possibility that the difference in band intensity was an artifact of the use of unequal quantities of protein from the two samples, which was standardized on the basis of quantification against BSA using Bradford reagent, by carrying out duplicate analyses in which the SLC30A5 promoter probe was replaced with a double-stranded IRD-labeled oligonucleotide probe including the Oct-1 binding sequence (TGTCGAATGCAAATCACTAGAA; Oct-1 binding site underlined). No difference in band intensities between the two samples (3 and 150 μm zinc) was observed with this probe sequence, confirming that equal quantities of protein were used to detect binding to the SLC30A5 promoter probe sequence (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

EMSA to reveal an increase in the abundance of a protein in Caco-2 cells binding upstream of the start of transcription in the SLC30A5 gene upon treatment with 150 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc. A, an IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel, either before or after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from Caco-2 cells treated with either 3 μm or 150 μm zinc and in the absence or presence of an excess (200-fold) of unlabeled probe, as indicated. The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts. Data are three representative analyses from a total of nine. B, the intensity of the major band in each of the data sets for the 150 μm zinc concentration, determined using UviPhotoMW image analysis software, was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding band at the 3 μm zinc concentration and plotted as mean ± S.E. (error bars) for the two different zinc concentrations, as indicated; n = 9; **, p < 0.01 by Student's unpaired t test. C, an IRD-labeled oligonucleotide probe (50 fmol) including the Oct-1 binding site was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel, either before or after incubation with 5 μg of Caco-2 cell lysate from cells treated with either 3 or 150 μm zinc, as indicated. Equal intensity of the major band (indicated by the arrow) at both zinc concentrations confirms the use of equal quantities of protein in the EMSA analyses.

Identification of the Binding Site of the Zinc-induced Nuclear Protein in the SLC30A5 Promoter

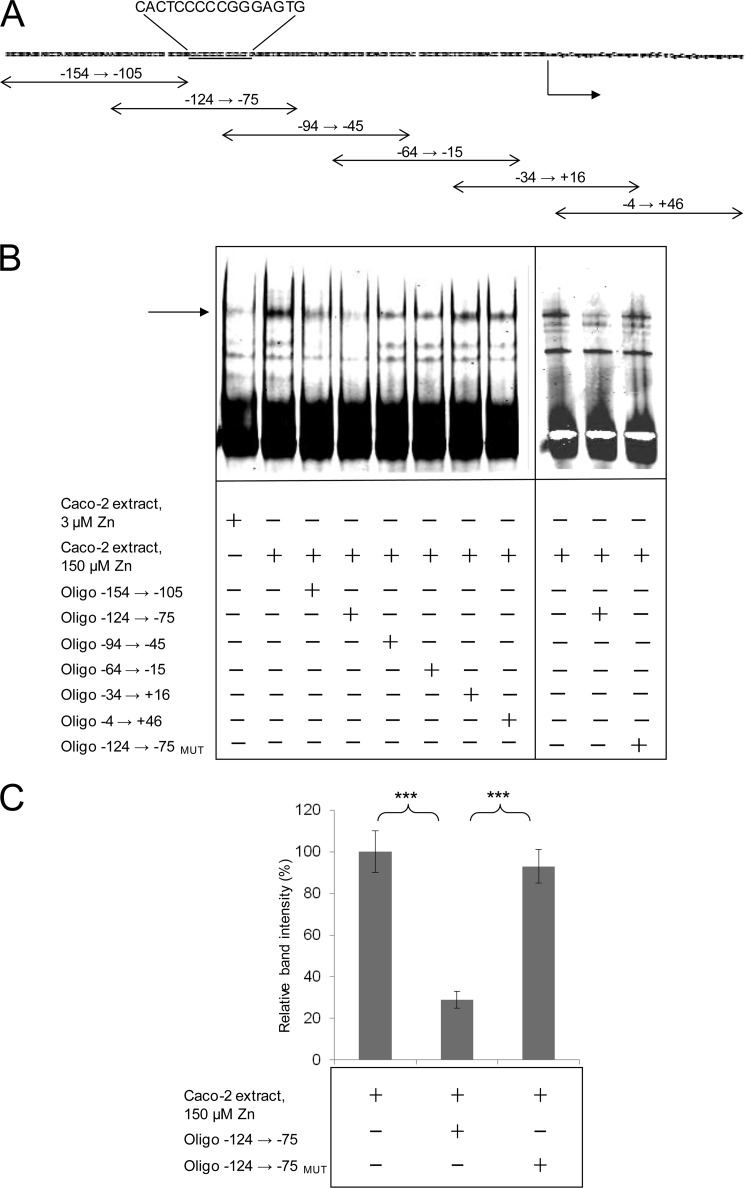

We used a series of overlapping double-stranded oligonucleotides, each 50 bp in length and overlapping by 20 bp (Fig. 2A), to map the position of the binding site for this zinc-regulated protein factor through competition for the binding site on the probe sequence, detected by EMSA. All oligonucleotides were added in a 200-fold excess relative to the labeled probe sequence. Oligonucleotide −124 to −75 was the most effective in inhibiting binding of the protein factor to the labeled probe sequence (Fig. 2, B and C), indicating that the site of protein binding is within this sequence. Inspection of the corresponding sequence revealed a 7-(2)-7 palindromic sequence (CACTCCC(CC)GGGAGTG; 7-bp palindromes underlined) corresponding with positions −91 to −76 bp upstream of the predicted start of transcription (end of the 5′-UTR). We refer to this palindromic sequence as the ZTRE. Random mutation of the ZTRE (to GGTAGCC(CC)GGGAGTG) in the double-stranded competitor abolished competition for protein binding with the labeled probe sequence, as detected by EMSA (Fig. 2, B and C), confirming that this is the binding site of the zinc-regulated protein factor. The test competitor that overlapped in the 3′ region with this oligonucleotide (−94 to −45) also included the ZTRE sequence but competed less effectively with the probe for protein binding, indicating that the context of ZTRE is important. A possible interpretation of this observation is that sequences 5′ of the ZTRE in SLC30A5 may also be involved in binding of the regulatory protein factor, possibly through interactions with other proteins within a complex.

FIGURE 2.

EMSA to identify double-stranded oligonucleotides that compete with the DNA sequence upstream of the start of transcription in the SLC30A5 gene for binding of a zinc-induced nuclear protein. A, relationship to the SLC30A5 promoter sequence used as the probe in EMSA of 50-bp double-stranded oligonucleotides tested as competitors for protein binding. The arrow indicates the start of transcription. The ZTRE sequence is highlighted. B, an IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with either 3 or 150 μm zinc and in the absence or presence of specific, double-stranded oligonucleotides (200-fold excess), as indicated. The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts. In the oligonucleotide −124 → −75MUT, the ZTRE sequence (CACTCCC-CC-GGGAGTG) was mutated to the random sequence GGTAGCC(CC)GGGAGTG. C, the intensity of the major band for the 150 μm zinc concentration (as in B; determined using UviPhotoMW image analysis software) in the presence of specific oligonucleotide competitors (200-fold excess), as indicated, was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding band in the absence of competitor and plotted as mean ± S.E. (error bars). n = 23 for no added oligonucleotide; n = 18 for oligonucleotide −124 → −75; n = 13 for oligonucleotide −124 → −75MUT; **, p < 0.01 by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

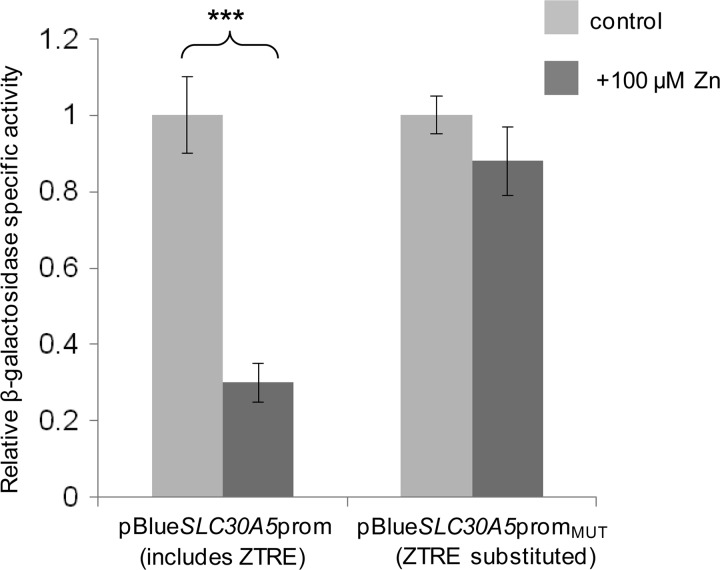

To determine if binding of the zinc-regulated protein factor to the ZTRE mediates the observed zinc-induced transcriptional repression of SLC30A5 promoter-reporter constructs that we reported previously (21), we replaced the ZTRE sequence in the SLC30A5 promoter-reporter construct pBlueSLC30A5prom (with the random sequence TCAGGAT-CC-CATTCAA) to generate pBlueSLC30A5promMUT and measured the response of both constructs to increasing the extracellular zinc concentration of Caco-2 cells transfected 24 h previously from 3 to 100 μm. Transcription of the β-galactosidase reporter gene was no longer suppressed at the higher zinc concentration in the construct lacking the ZTRE (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the ZTRE mediates this response.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of mutating the ZTRE motif on the response of the SLC30A5 promoter to elevated extracellular zinc concentrations in Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were transfected transiently with promoter-reporter plasmids containing the −950 to +50 region of the SLC30A5 promoter in which the ZTRE (positions −91 to −76) was either present (pBlueSLC30A5prom) or replaced with a random nucleotide sequence (pBlueSLC30A5promMUT). Twenty-four hours following transient transfection, Caco-2 cells were maintained in serum-free medium supplemented with either 3 μm (control) or 100 μm zinc, as indicated, (added as ZnSO4) for an additional 24 h. Promoter activity was measured as β-galactosidase reporter gene activity in cell lysates and expressed relative to protein concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. (error bars) normalized to the control condition for n = 9. ***, p < 0.001 by Student's unpaired t test.

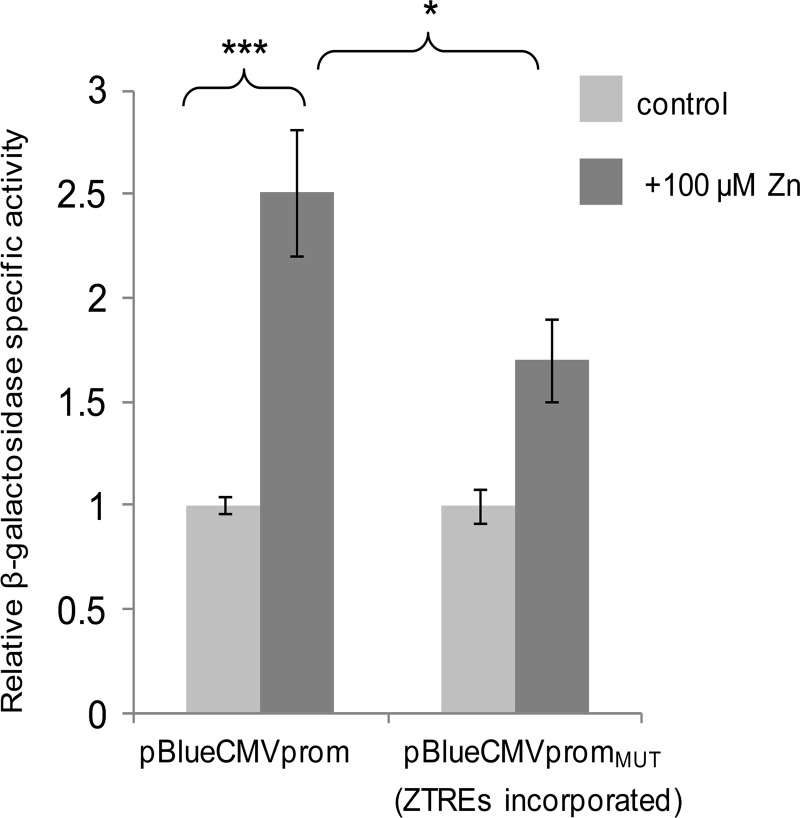

An element including five copies of the ZTRE sequence (CACTCCCCCGGGAGTGTTCACTCCCCACACTCCCCCGGGAGTG) was incorporated into the CMV promoter in a promoter-reporter plasmid construct to determine if the addition of this regulatory element was sufficient to confer transcriptional repression in response to zinc. The unmodified construct comprised bases 541–1128 of the CMV promoter sequence, deposited as GenBankTM entry X03922, upstream of the β-galactosidase reporter gene in the vector pBlue-TOPO (Invitrogen); the ZTRE element was introduced between bases 952 and 953. Although our preliminary measurements predicted that the unmodified CMV promoter would be refractory to regulation by zinc, we observed an unexpected significant increase in activity of this promoter in response to 100 μm zinc in transiently transfected Caco-2 cells (Fig. 4). However, there was a significant difference between activity of the unmodified CMV promoter and activity of the CMV promoter into which the ZTREs were incorporated when cells were exposed to 100 μm zinc, such that the apparent zinc responsiveness of the unmodified CMV promoter was attenuated to a non-statistically significant level by the addition of the ZTRE sequences (Fig. 4). These observations are consistent with the addition of the ZTRE resulting in transcriptional repression at elevated zinc concentrations that opposed transcriptional activation mediated through other (unidentified) zinc-responsive elements.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of incorporating the ZTRE motif on the response of the CMV promoter to elevated extracellular zinc concentrations in Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were transfected transiently with promoter-reporter plasmids containing the CMV promoter (bases 541–1128 of the sequence deposited as GenBankTM entry X03922) either in its unmodified form (pBlueCMVprom) or incorporating an additional element including copies of the ZTRE at positions 960–961 (pBlueCMVpromMUT). Twenty-four hours following transient transfection, Caco-2 cells were maintained in serum-free medium supplemented with either 3 μm (control) or 100 μm zinc, as indicated (added as ZnSO4), for an additional 24 h. Promoter activity was measured as β-galactosidase reporter gene activity in cell lysates and expressed relative to protein concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. (error bars) normalized to the control condition for n = 3–9. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

Investigation of the Requirement for Zinc to Permit Binding of the Nuclear Protein to the ZTRE

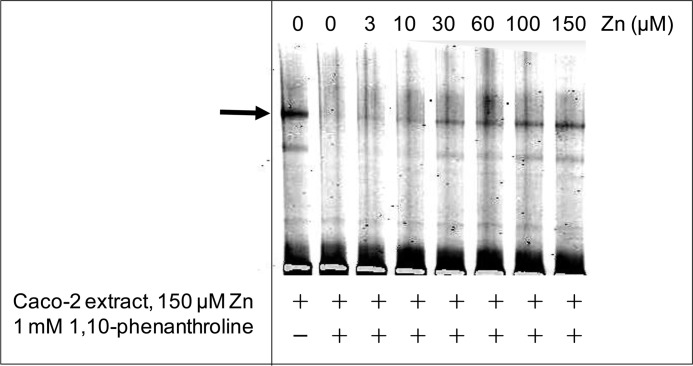

To investigate if the binding interaction between the zinc-induced protein that binds to the ZTRE in the SLC30A5 promoter is affected by zinc availability, we used EMSA to investigate the effect of removal of available zinc by the addition of the zinc chelator 1,10-phenanthroline to the binding reaction. Binding between the probe and protein was no longer detected under these conditions but was restored progressively upon the addition of increasing concentrations of excess zinc to the binding reaction in the presence of the chelator, demonstrating that the binding interaction is sensitive to zinc availability (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

The effect of zinc on the binding interaction between the zinc-induced nuclear protein and the ZTRE. An IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with 150 μm zinc in the absence or presence of a 1 mm concentration of the zinc chelator 1,10-phenanthroline, as indicated, at progressively increasing concentrations of added zinc (as ZnSO4). The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts.

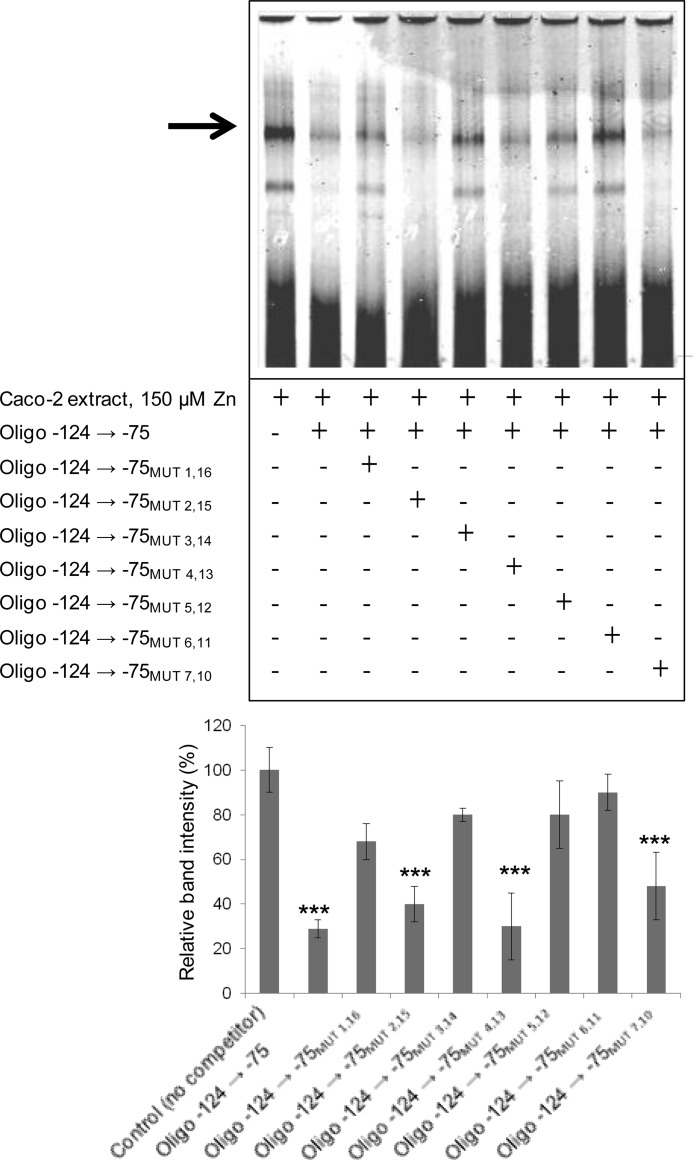

Refinement of the ZTRE Sequence

To investigate flexibility within the ZTRE with respect to base substitution, we used a series of double-stranded oligonucleotide competitors in the EMSA binding reaction into which we incorporated sequential substitutions at each position of the palindrome (making the equivalent change in both halves). Typical results are presented as Fig. 6. This approach indicated that binding of the protein we detect requires an invariant C at positions 1, 3, 5, and 6 but that there is some degeneracy at positions 2, 4, and 7, such that a likely functional ZTRE can be specified as C(A/C)C(T/A/G)CC(C/T)Nn(G/A)GG(A/T/C)G(T/G)G, including only one of the allowed base substitutions (simultaneously in both halves of the palindrome). It is likely that flexibility in both sequence and length is permitted in the region linking the two halves of the palindrome. We tested additional double-stranded oligonucleotides as competitors with the EMSA probe for protein binding, and in these, we incorporated each of the allowed substitutions in pairwise combinations (again, simultaneously in both halves of the palindrome). None of these oligonucleotides retained the ability to compete with the probe for binding to the protein factor. Thus we conclude that, based on current data, the ZTRE as described above cannot be refined further. All of the oligonucleotides used in these experiments are listed in supplemental Table S2.

FIGURE 6.

Representative EMSA to identify a partial consensus sequence for the ZTRE. A, an IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with 150 μm zinc and in the absence or presence of specific, double-stranded oligonucleotides (200-fold excess), as indicated. The different oligonucleotides included different modifications to the ZTRE sequence, made as single substitutions at both halves of the palindromic sequence at the positions indicated. The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts. B, intensity of the major band for the 150 μm zinc concentration (as in A; determined using UviPhotoMW image analysis software) in the presence of the oligonucleotide competitors, as indicated, was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding band in the absence of competitor and plotted as mean ± S.E. (error bars). n = 18 for oligonucleotide −124 → −75; n = 4 for all other oligonucleotides. ***, p < 0.001 by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

Identification of Other Genes, Including CBWD Genes, That Include the ZTRE

To determine if the ZTRE is a feature of the promoter region of other genes, we searched the human genome sequence for matches to the SLC30A5 ZTRE sequence using the program Fuzznuc (EMBOSS) and allowing one mismatch (corresponding to each half of the palindrome), with the linker region specified as between 0 and 8 bp. The output was inspected manually to determine the approximate position of each candidate ZTRE identified relative to the transcription start site. We located 34 occurrences of the sequence within 2 kb upstream of a transcription start site (supplemental Table S3). Particularly notable from the output was the occurrence multiple times in the list of matches to the ZTRE of genes belonging to the CBWD (COBW domain-containing) family. A ZTRE sequence (CACGCCC(A/C)(G/T)GGGCGTG) was identified ∼200 bp upstream from the transcription start site in multiple members of this family. Because bacterial homologs of the CBWD genes are being studied in the context of metal homeostasis (32), we pursued this observation further. We hypothesized that the ZTRE in the CBWD genes has the same function as in SLC30A5, and so we predicted that (i) increasing the zinc concentration of the extracellular medium would reduce levels of CBWD mRNAs and protein in Caco-2 cells; (ii) expression of a reporter gene driven by CBWD regions upstream of the ORF would be reduced when zinc concentration of the extracellular medium was increased; and (iii) mutation of the ZTRE in a CBWD promoter-reporter construct would abrogate this response to zinc. Human CBWD genes are numbered 1–6, with CBWD4 being designated a pseudogene. CBWD1, -3, -4, -5, and -6 are on chromosome 9, with CBWD1 in the subtelomeric region of the p-arm and CBWD3, -4, -5, and -6 clustered around 9q13. CBWD2 is on chromosome 2 at 2q13 (supplemental Fig. S1). Sequence alignment of all CBWD gene products and promoter sequences (ClustalW2) reveals a remarkable degree of conservation; the sequences are almost invariant (supplemental Fig. S1).

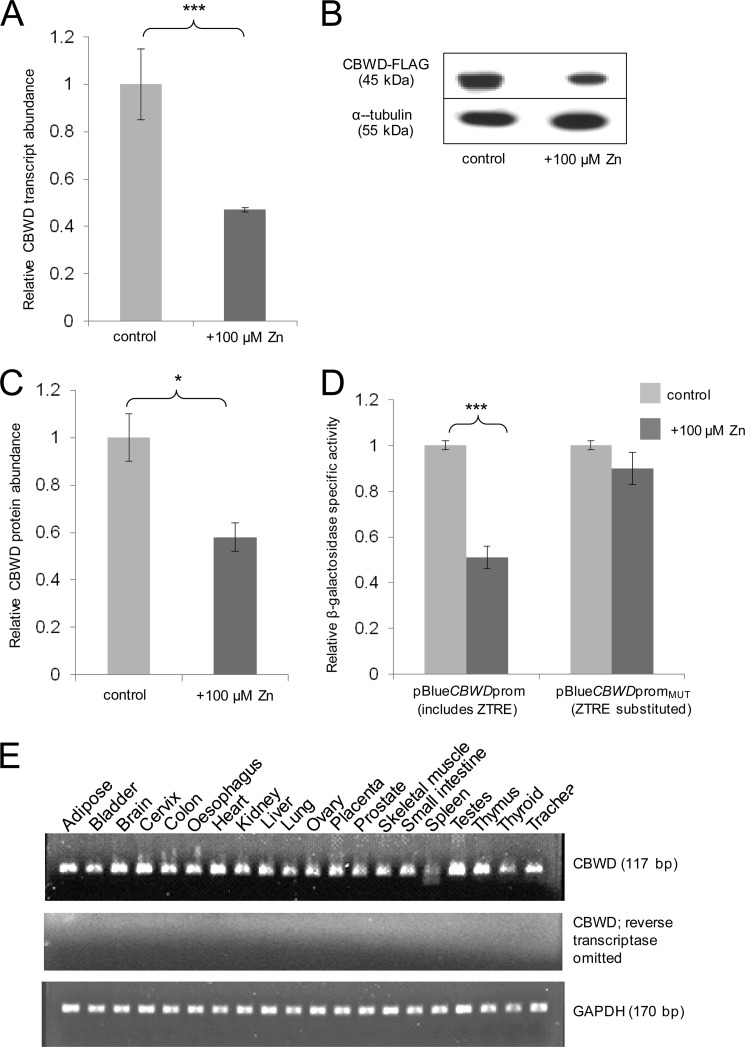

Effect of Zinc on CBWD Expression

We used quantitative RT-PCR to determine the effect of extracellular zinc concentration on CBWD gene expression in Caco-2 cells using a primer pair that would detect transcripts from all active CBWD genes. As predicted, CBWD mRNA was reduced in Caco-2 cells (to ∼50% of control levels) by the addition of 100 μm zinc to the cell culture medium (3 μm zinc) (Fig. 7A), and levels of recombinant CBWD protein, expressed in CHO cells and detected on Western blots by virtue of a C-terminal FLAG tag using anti-FLAG antibody, showed a similar reduction in response to the same treatment (Fig. 7, B and C). We designed and generated a promoter-reporter construct based on the sequence of the human CBWD1 gene and including the region −1077 to +95 relative to the transcription start site (pBlueCBWDprom). We also generated an equivalent construct (pBlueCBWDpromMUT) with the ZTRE sequence (positions −133 to −118 relative to the transcription start site) substituted with the same random sequence (TCAGGAT-CC-CATTCAA) as used to replace the ZTRE in the SLC30A5 promoter-reporter construct pBlueSLC30A5prom to generate pBlueSLC30A5promMUT. The 1175-bp promoter region in pBlueCBWDprom differs in 41 positions only between all human CBWD genes (see supplemental Fig. S1); thus, the construct is likely to provide data relevant to the regulation by zinc of all active CBWD genes. As predicted, expression of the β-galactosidase reporter gene was reduced in Caco-2 cells transfected transiently with the CBWD promoter-reporter construct at 100 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc, and this response was not observed using the equivalent construct that lacked the ZTRE sequence (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

CBWD expression and response to increased extracellular zinc concentration. A, CBWD transcript levels in RNA from Caco-2 cells measured by quantitative RT-PCR and expressed relative to GAPDH. Confluent cells were maintained for 24 h, 24 h after seeding, in serum-free medium containing zinc sulfate added to 3 μm (control) or 100 μm, as indicated. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 6. ***, p < 0.001 by Student's unpaired t test; B, representative Western blot showing signal intensities for recombinant CBWD3 protein expressed in CHO cells with a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag and detected using anti-FLAG antibody and for α-tubulin (loading control) after maintenance of cells for 24 h in serum-free medium containing zinc sulfate added to 3 μm (control) or 100 μm, as indicated, 24 h after transfection with the CBWD3 expression construct (pCMV6Entry-CBWD3; Origene). Molecular weights are indicated. C, data derived by densitometric quantification of band intensities from Western blots as described for B, determined using UviPhotoMW image analysis software, expressed as the ratio of the CBWD1 signal to the α-tubulin signal and normalized to the control condition then expressed as mean ± S.E. for n = 7. *, p < 0.05 by Student's unpaired t test. D, effect of mutating the ZTRE motif on the response of the CBWD1 promoter to elevated extracellular zinc concentrations in Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were transfected transiently with promoter-reporter plasmids containing the −1077 to +95 region of the CBWD1 promoter in which the ZTRE (positions −133 to −118) was either present (pBlueCBWDprom) or replaced with a random nucleotide sequence (pBlueCBWDpromMUT). Twenty-four hours following transient transfection, Caco-2 cells were maintained in serum-free medium supplemented with either 3 μm (control) or 100 μm zinc, as indicated (added as ZnSO4), for an additional 24 h. Promoter activity was measured as β-galactosidase reporter gene activity in cell lysates and expressed relative to protein concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. normalized to the control condition for n = 24 for pBlueCBWDprom and n = 12 for pBlueCBWDpromMUT. ***, p < 0.001 by Student's unpaired t test. E, expression of CBWD in a panel of human tissues detected by RT-PCR. Primers specific to CBWD and to GAPDH (positive control) were used in PCRs as indicated after reverse transcription of total RNA samples from the tissues as identified. No products were observed when reverse transcriptase was omitted from reactions, confirming the origin of the products as mRNA (not DNA contamination). Product sizes are indicated.

CBWD Expression Profile in Human Tissues

We screened a panel of human RNAs from a variety of different tissues (FirstChoice Human Total RNA Survey Panel (Ambion)) for expression of CBWD transcripts by RT-PCR and detected expression in all tissues included (Fig. 7E).

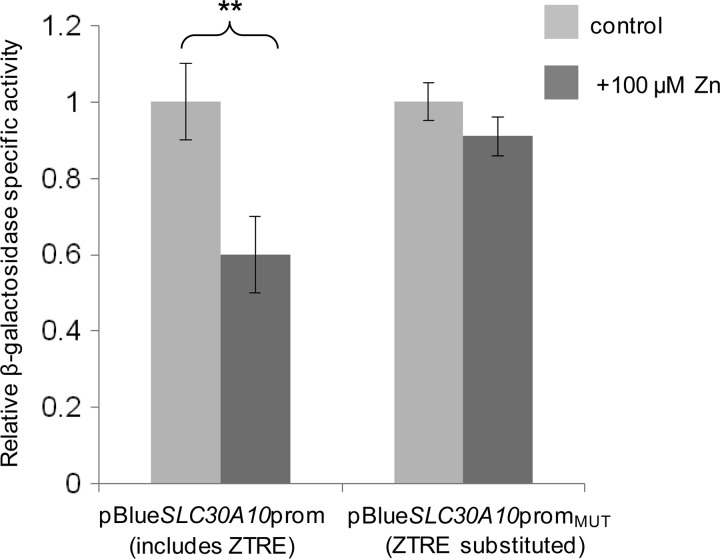

Investigation of the Role of the ZTRE in the Response of the SLC30A10 Gene to Zinc

We recently made novel observations concerning the expression and function of ZnT10 and measured a reduction in ZnT10 mRNA in SH-SY5Y and Caco-2 cells in response to increasing the extracellular zinc concentration from 3 to 100 μm (33), so we searched the SLC30A10 sequence for occurrences of the ZTRE using the sequence C(A/C)C(T/A/G)CC(C/T)N0–16(G/A)GG(A/T/C)G(T/G)G. We identified a sequence, CCCACCT(GTGGCTGCGCGCG)GGGTGGG, spanning nucleotides 140–166 of the ZnT10 transcript sequence NM_0187132. This sequence differs from the ZTRE in SLC30A5 at two positions in the upstream half of the (imperfect) palindromic region and at one position in the downstream half; these differences are permissive according to our analysis of substitutions that retain binding of the protein factor identified by EMSA. We thus predicted that SLC30A10 promoter activity would respond to zinc in a manner similar to SLC30A5 and CBWD. We generated SLC30A10 promoter-reporter constructs (−762 to +180, relative to the transcription start site, in pBlue-TOPO) in which the candidate ZTRE (positions +58 to +84) was either retained (pBlueSLC30A10prom) or substituted (pBlueSLC30A10promMUT), retaining the longer interpalindrome linker region. We transfected Caco-2 cells with these constructs to investigate if the SLC30A10 gene is repressed at the transcriptional level by zinc acting through the same mechanism as for SLC30A5. As predicted, reporter gene expression from the SLC30A10 promoter sequence was repressed at the higher zinc concentration (100 μm compared with 3 μm), but this response was abrogated by substitution of the candidate ZTRE (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of mutating the ZTRE motif on the response of the SLC30A10 promoter to elevated extracellular zinc concentrations in Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were transfected transiently with promoter-reporter plasmids containing the −762 to +180 region of the SLC30A10 promoter in which the ZTRE (positions +58 to +84) was either present (pBlueSLC30A10prom) or replaced with a random nucleotide sequence (pBlueSLC30A10promMUT). Twenty-four hours following transient transfection, Caco-2 cells were maintained in serum-free medium supplemented with either 3 μm (control) or 100 μm zinc, as indicated (added as ZnSO4), for an additional 24 h. Promoter activity was measured as β-galactosidase reporter gene activity in cell lysates and expressed relative to protein concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. (error bars) normalized to the control condition for n = 6. **, p < 0.01 by Student's unpaired t test.

Zinc Selectivity of the ZTRE

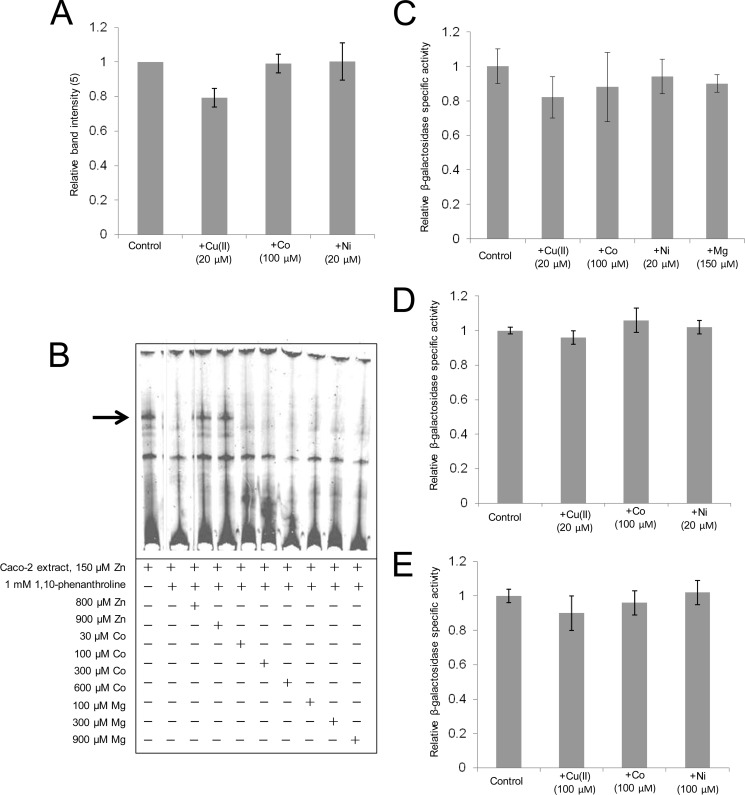

We explored the metal selectivity of transcriptional regulation through the ZTRE using strategies based both on use of EMSA and promoter-reporter constructs. Use in EMSA, with the SLC30A5 probe, of nuclear extracts prepared from Caco-2 cells after treatment for 24 h with copper(II) (20 μm), nickel (20 μm), and cobalt (100 μm) resulted in no increase in band intensity compared with the use of extract prepared from cells to which additional metal was not added (Fig. 9A). Moreover, under conditions of metal chelation using 1,10-phenanthrolione addition of cobalt or magnesium to binding reactions subsequently analyzed by EMSA failed to restore protein binding to the probe (Fig. 9B). We investigated if treatment of Caco-2 cells transfected with each of the promoter-reporter constructs for SLC30A5, SL30A10, and CBWD with other metals affected reporter gene activity compared with measurements made under equivalent conditions but with no additional metal added to the medium and observed no effects (Fig. 9, C, D, and E). We thus find no evidence that metals other than zinc affect gene expression through the ZTRE.

FIGURE 9.

Zinc selectivity of transcriptional regulation through the ZTRE. A, data derived by densitometric analysis of the major band observed by EMSA using an IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with 3 μm zinc and with additional copper, cobalt, or nickel at the concentrations indicated. Data derived using UviPhotoMW image analysis software are expressed as a percentage of the band at the 3 μm zinc concentration and plotted as mean ± S.E. (error bars) for n = 3. B, effect of cobalt and magnesium on the binding interaction between the zinc-induced nuclear protein and the ZTRE. An IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with 150 μm zinc and in the presence of 1 mm of the zinc chelator 1,10-phenanthroline at progressively increasing concentrations of added zinc, cobalt, or magnesium. The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts. C, D, and E, the effect of different metals on the activity of the SLC30A5 (C), CBWD1 (D), and SLC30A10 (E) promoters. Caco-2 cells were transfected transiently with promoter-reporter plasmids containing the −950 to +50 region of the SLC30A5 (pBlueSLC30A5prom) (C), the −1077 to +95 region of the CBWD1 promoter (pBlueCBWDprom) (D), or the −762 to +180 region of the SLC30A10 promoter (pBlueSLC30A10prom) (E). Twenty-four hours following transient transfection, Caco-2 cells were maintained in serum-free medium supplemented with 3 μm zinc (control) or with additional cobalt, magnesium, copper, or nickel at the concentrations indicated for an additional 24 h. Promoter activity was measured as β-galactosidase reporter gene activity in cell lysates and expressed relative to protein concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. normalized to the control condition for n = 3–9.

Presence of the ZTRE in Other SLC30 Family Genes

A search of the 5′ UTRs plus 500 bp upstream of the transcription start site of all other known members of the SLC30 family, of which there are 10 members in total, revealed sequences concurring with the ZTRE, allowing separation of the two palindrome halves by up to 100 bp, in SLC30A1, SLC30A3, SLC30A4, and SLC30A7. Of these genes, the two halves of the palindromic sequence are separated by the greatest distance (72 bp) in SLC30A1. Thus, only SLC30A2, SLC30A6, SLC30A8, and SLC30A9 appear to lack the ZTRE. In contrast, applying the same criteria to four members of the SLC39 family of zinc transporters (SLC39A1, SLC39A2, SLC30A3, and SLC39A4; selected randomly from the total of 14 members) and five randomly selected genes with no known link to zinc transport or homeostasis (SIRT1, GDH/6PGL, GPX1, SLC2A2, and ATP2A2) revealed the ZTRE in only one of these genes (ATP2A2). The regions upstream of the start of translation with ZTREs highlighted for these genes are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. On the basis of this analysis, the ZTRE appears to be a particular feature of the SLC30 family, suggesting that multiple members are regulated in a coordinated manner at the level of transcription in response to zinc through a common mechanism.

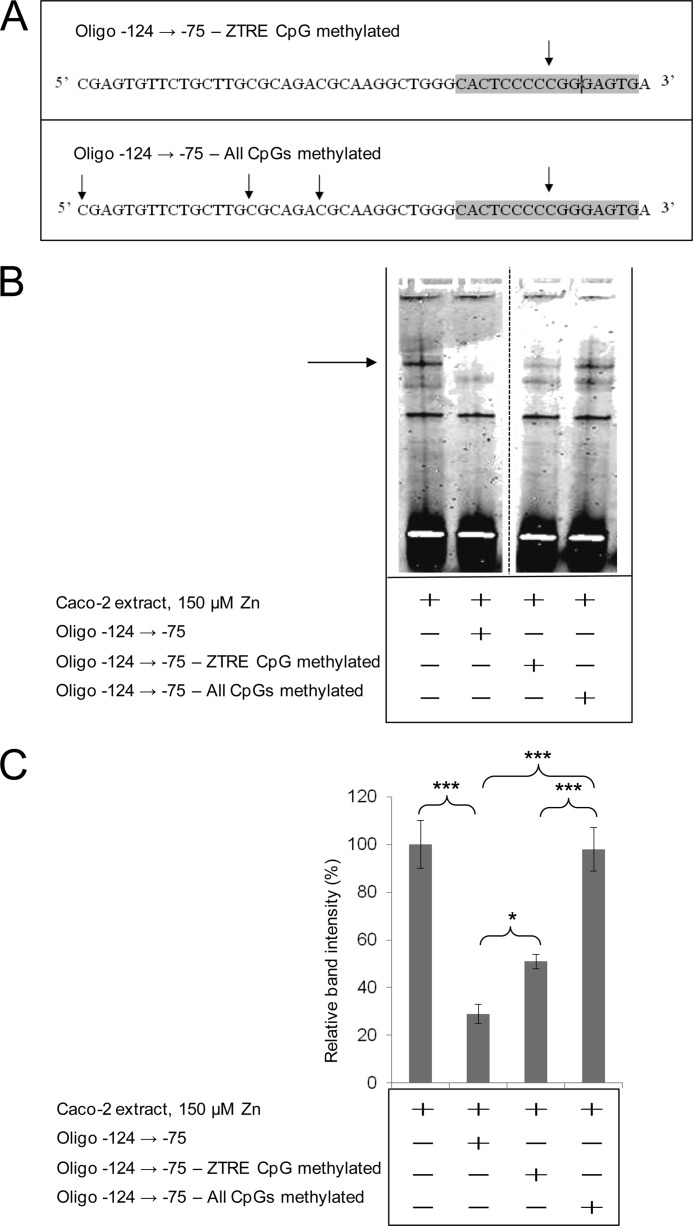

Investigation of Effects of DNA Methylation on Protein Binding to the ZTRE

The ZTRE sequence C(A/C)C(T/A/G)CC(C/T)Nn(G/A)GG(A/T/C)G(T/G)G and the specific ZTRE in SLC30A5, CBWD, and SLC30A10 genes include CpG dinucleotides, which are potential sites for DNA methylation. We are currently investigating age-related changes in DNA methylation of genes with a role in zinc homeostasis and wished to determine if binding of the putative transcriptional regulatory factor to the ZTRE was affected by DNA methylation. We thus investigated if methylation of the double-stranded oligonucleotide competitor affected the protein binding interaction we observed using EMSA with the SLC30A5 probe sequence. We tested oligonucleotide competitors synthesized with a methylated cytosine base at only the CpG site within the ZTRE and also with methylated cytosines at all four CpG sites in the 50-bp competitor sequence (Fig. 10A). The ability of the oligonucleotide to compete with the probe sequence for protein binding was reduced in both cases (Fig. 10B). It appeared that methylation of the whole competitor sequence completely abrogated protein binding, whereas the effect of methylation at only the CpG within the ZTRE was partial (supported by densitometric quantification of the intensity of the specific band observed on EMSA (Fig. 10C)).

FIGURE 10.

The effect of DNA methylation on the binding of protein to the ZTRE in the SLC30A5 promoter region. A, the position of methylated CpG sites (arrows) and the ZTRE (shaded) in the oligonucleotide −124 → −75 used as a test competitor in forms where only the site in the ZTRE or all sites were methylated. B, an IRD-labeled probe (50 fmol), corresponding to the region −156 to +46 of the SLC30A5 gene, was electrophoresed through a non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel after incubation with 5 μg of nuclear extract from cells treated with 150 μm zinc and in the absence or presence of the double-stranded oligonucleotides (200-fold excess), as indicated. The arrow indicates the position of the major band representing probe bound to proteins in the cell extracts. C, intensity of the major band (as in B; determined using UviPhotoMW image analysis software) in the presence of the oligonucleotide competitors, as indicated, was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding band in the absence of competitor and plotted as mean ± S.E. (error bars). n = 23 for no added oligonucleotide; n = 17 for the unmethylated oligonucleotide −124 → −75; n = 4 for both methylated oligonucleotides. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

DISCUSSION

We have established that zinc-mediated transcriptional repression of the human SLC30A5 gene involves the zinc-dependent binding of a zinc-regulated protein factor to a palindromic sequence, the ZTRE, at positions −91 to −76 bp upstream of the end of the 5′-UTR, defining a novel mechanism for zinc-mediated transcriptional regulation. The increased abundance of this protein factor in nuclear extract from cells maintained at 150 μm compared with 3 μm extracellular zinc could reflect either higher levels of expression in the cell (including effects resulting from increased synthesis or reduced degradation) or trafficking into the nucleus at the higher zinc concentration (or both). We exclude the possibility that ZTRE-dependent changes in gene expression are also dependent upon MTF1 based on an analysis4 we undertook involving siRNA-mediated knockdown of MFT1 in Caco-2 cells, followed by analysis by hybridization of RNA to a DNA oligonucleotide microarray. As expected, the response to increased extracellular zinc of known MTF1-regulated genes, including SLC30A1 and several of the metallothioneins, was attenuated by the reduction in MTF1 levels we achieved. In contrast, SL30A5, SLC30A10, and CBWD were not among the group of genes whose response to zinc was affected by MTF1 knockdown.

Sequences that concur with a ZTRE sequence established to be permissive for binding of the putative transcriptional regulatory protein that acts at this site occur also in upstream regions close to the coding sequence in the SLC30A10 and CBWD genes (among others), and we have confirmed that these sequences function in the same way as the ZTRE in SLC30A5 to confer transcriptional repression in response to zinc.

A transcriptional regulatory mechanism based on this principle, zinc-induced binding of a transcriptional repressor, has not previously been described in a eukaryotic system, but this mode of operation is, in principle, analogous to the regulation of the E. coli znuABC operon by the zinc-induced transcriptional repressor Zur (5). The almost perfect palindromic binding site sequence for Zur (TGTGATATTATAACA) shows no sequence similarity with the ZTRE identified in the present study. The current findings do not exclude the possibility that a separate transcriptional regulatory mechanism operates in mammalian cells under conditions of zinc deficiency to increase the expression of genes involved in zinc scavenging, such as those involved in high affinity uptake across the plasma membrane (e.g. ZIP4 (SLC39A4) (34), in which zinc-dependent transcriptional regulation by KLF4 appears to play a role (22)) or release from intracellular organelles under conditions of zinc deficiency.

Our search of the human genome for genes including the ZTRE identified the family of CBWD genes (coding for COBW domain-containing proteins), which we believe may play an important role in mammalian cellular zinc homeostasis, possibly extending to intracellular homeostatic regulation of other metals. Members of this gene family, named because they contain a domain homologous to the CobW protein from Pseudomonas dentrificans (35), appear be represented widely across the phyla. The P. dentrificans gene was identified by mutational analysis of proteins involved in the cobalamin/vitamin B12 synthesis pathway (36), but a specific function for the gene product in this pathway has not been established. Higher organisms lack the capability to synthesize vitamin B12, so the protein probably fulfills other functions. The CBWD proteins, in which the CobW domain is the C-terminal portion, include an N-terminal domain belonging to the P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase superfamily. This domain is of ancient evolutionary origin and includes the nucleoside triphosphate-binding P-loop along with Walker A (GXXXXGK(S/T)) and Walker B (hhhh(D/E), where h represents a hydrophobic residue) motifs (37). Within the nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase superfamily, the CBWD proteins are within the GTP-binding G3E family (COG0523), characterized by the GXXGXGK(S/T) variant of the Walker A motif plus a conserved Mg2+-binding aspartate residue (38). The G3E family also includes the bacterial UreG subfamily, involved in incorporation of nickel into the metallocenters of urease and hydrogenase enzymes (39), and in Bacillus subtilis and other prokaryotes, G3E family members are found within operons regulated by the zinc-dependent transcriptional repressor Zur, along with genes coding forms of metal-dependent enzymes in which the more “usual” metal is replaced by an alternative (e.g. an iron-dependent rather than zinc-dependent carbonic anhydrase) (32). A role for CBWD proteins, including regulation of the corresponding genes by zinc, is thus being uncovered in bacteria. We are not aware of any previous reports that mammalian CBWD genes are regulated by zinc, so our findings are highly novel and may point toward the CBWD proteins playing a fundamental role in zinc homeostasis in metazoans. It appears that the multiple human CDBW genes arose through recent segmental duplication of telomeric genes (35). CBWD1, -3, -4 (pseudogene), -5, and -6 are all on chromosome 9, with CBWD1 in the subtelomeric region of the p-arm and CBWD3, -4, -5, and -6 in the pericentromeric region of the q-arm. CBWD2 is in the pericentromeric region on the q-arm of chromosome 2. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of CBWD1, -2, -3, -5, and -6 reveals extremely tight conservation (97–99% identity; see supplemental Fig. S1). This tight conservation, despite the relatively recent nature of duplication events leading to the multiple genes, suggests that all are under selective pressure for an essential function(s). Gene multiplicity may be a means to achieve higher levels of expression or expression in a wide variety of cell types in which particular CBWD genes are inactive. Our analysis that identified the presence of CBWD transcripts in all human tissues screened by RT-PCR could not distinguish between specific isoforms, so the latter remains a question for further investigation. Thus, at present, the function of the CBWD genes remains unknown, but a role(s) in metal homeostasis appears likely.

Occurrence of the ZTRE in the upstream region of the gene coding for the NMDA receptor subunit 2C merits comment, in view of the known complex effects of zinc on NMDA receptor function (see Ref. 40 and references therein). Of particular relevance is that maternal zinc deficiency reduced the expression of NMDA receptor subunits A and B (subunit C was not measured) in the rat brain (41). The occurrence of the ZTRE in the promoter region of the gene for Toll-like receptor 10 may provide an additional link between Toll-like receptor signaling and zinc homeostasis. Activation of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in dentritic cells reduces intracellular zinc concentration through changes in zinc transporter expression (42). Future research should examine directly the response to zinc of the genes with the ZTRE in the upstream region to establish unequivocally if they are responsive or refractory to transcriptional regulation by zinc.

We also identified a ZTRE in the 5′-UTR of the SLC30A10 gene and demonstrated that it is functional in a promoter-reporter construct. We reported recently a reduction in ZnT10 mRNA in Caco-2 and human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells when additional zinc was added to the extracellular medium (33). We observed that the ZnT10 protein traffics from the Golgi apparatus in SH-SY5Y cells when the extracellular zinc concentration is increased and showed that it functions to reduce cytosolic zinc concentration. These observations may be commensurate with a mode of transcriptional regulation through which expression is repressed at higher zinc levels if the primary function of ZnT10 is delivery of zinc to proteins in the Golgi apparatus rather than homeostasis of cytosolic concentrations. With the exception of ZnT2, ZnT6, ZnT8, and ZnT9, inspection of SLC30 family genes revealed sequences that concur with what we identify thus far to be permissible as a ZTRE with respect to protein binding in the 5′-UTR and 500-bp region immediately upstream of the start of transcription, supporting the idea of coordinated regulation of multiple members of the gene family through this transcriptional regulatory mechanism. It should be noted that the halves of the palindromic sequence are separated by up to 72 bp (in SLC30A1) and that we have not established the maximum permissible distance between the two halves. The substitutions to the ZTRE sequence in the competitor oligonucleotide that abrogated protein binding to this region as detected by EMSA were made in only one half of the palindromic sequence; thus, it appears that both sections of sequence are necessary. It is feasible that two linearly separated sequences in DNA come into proximity to allow binding to either a single protein or protein complex by virtue of the folding of DNA into chromatin. Further analyses are required to elucidate if such a situation allows function of these putative ZTREs in SLC30 family members other than SLC30A5 and SLC30A10.

Our search for genes including the ZTRE was limited by use of a search strategy that allowed only one mismatch compared with the sequence in SLC30A5. We observed that protein binding to the ZTRE was retained when nucleotides, found to be non-essential individually, were changed in pairs, and it is possible that other arrangements of nucleotides allow protein binding. It is thus likely that we will identify many more genes with possible functional ZTREs through a range of more sophisticated bioinformatic analyses that we are currently undertaking. A global understanding of zinc-regulated gene expression and, therefore, of zinc homeostasis in mammalian systems requires that the range and prevalence of genes regulated by zinc through the ZTRE should be defined. Identification of the transcriptional regulator that binds to the ZTRE is pivotal to achieving this level of understanding and is a current major focus of on-going work based around use of the ZTRE as a probe sequence to separate the protein from nuclear lysates.

A weaker band of higher mobility was affected by all treatments in parallel with the major band we quantified when applying EMSA to observe binding of the transcriptional regulatory protein to the ZTRE. A possible explanation for this observation is that a transcriptional regulatory protein complex, rather than a single protein, assembles at the ZTRE.

Epigenetic modification, in particular DNA methylation, can influence the binding of regulatory factors to DNA. It was demonstrated previously that the mammalian zinc-responsive transcriptional activator MTF1 can tolerate methylation of some CpG dinucleotides within its binding site, the MRE, but that methylation of other specific positions can interfere with binding (43). The ZTREs in the SLC30A5, SLC30A10, and CBWD promoters all include CpG dinucleotides (at different positions in the sequence). Using methylated oligonucleotide competitors of the −156 to +46 region of the SLC30A5 promoter for binding nuclear protein before analysis by EMSA, we found that methylation of the single CpG in the SLC30A5 ZTRE sequence reduced protein binding. However, methylation of all four CpGs in the 50-bp oligonucleotide competitor had a bigger effect in blocking protein binding. A possible explanation for this observation is that the protein that binds to the ZTRE is a component of a complex that spans some of these other sites. This hypothesis is supported by our observation that a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide that included the ZTRE but not the other CpG sites (−94 to −45) was less effective as a competitor than the oligonucleotide that included this region (−124 to −75). DNA methylation patterns change as individuals age and are modified by environmental factors, including toxins and components of the diet (reviewed in Ref. 44), so the effects of such influences on methylation of the ZTRE and surrounding sequence and possible consequences for zinc homeostasis should be explored.

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Research Grants BB/F019637/1 (to D. F.) and BB/D01669X/2 (to R. A. V.) plus a Ph.D. studentship supporting L. J. C. (awarded to D. F.); Medical Research Council Ph.D. studentships supporting K. A. J. (awarded to D. F.) and supporting H. J. B. (awarded to R. A. V.); the Tertiary Education Trust Fund through Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria (Ph.D. studentship supporting O. A. O.); and the Human Nutrition Research Centre, Newcastle University (vacation studentship supporting G. M. H.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S3.

L. J. Coneyworth, K. A. Jackson, J. Tyson, H. J. Bosomworth, E. van der Hagen, G. M. Hann, O. A. Ogo, D. C. Swann, J. C. Mathers, R. A. Valentine, and D. Ford, unpublished observations.

- MRE

- metal response element

- IRD

- infrared dye

- ZTRE

- zinc transcriptional regulatory element

- CBP

- CREB-binding protein

- CREB

- cAMP-responsive element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andreini C., Banci L., Bertini I., Rosato A. (2006) Counting the zinc proteins encoded in the human genome. J. Proteome Res. 5, 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Busenlehner L. S., Pennella M. A., Giedroc D. P. (2003) The SmtB/ArsR family of metalloregulatory transcriptional repressors. Structural insights into prokaryotic metal resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waldron K. J., Robinson N. J. (2009) How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Outten C. E., Outten F. W., O'Halloran T. V. (1999) DNA distortion mechanism for transcriptional activation by ZntR, a Zn(II)-responsive MerR homologue in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37517–37524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patzer S. I., Hantke K. (2000) The zinc-responsive regulator Zur and its control of the znu gene cluster encoding the ZnuABC zinc uptake system in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24321–24332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lyons T. J., Gasch A. P., Gaither L. A., Botstein D., Brown P. O., Eide D. J. (2000) Genome-wide characterization of the Zap1p zinc-responsive regulon in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7957–7962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu C. Y., Bird A. J., Chung L. M., Newton M. A., Winge D. R., Eide D. J. (2008) Differential control of Zap1-regulated genes in response to zinc deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 9, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao H., Eide D. J. (1997) Zap1p, a metalloregulatory protein involved in zinc-responsive transcriptional regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 5044–5052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacDiarmid C. W., Gaither L. A., Eide D. (2000) Zinc transporters that regulate vacuolar zinc storage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19, 2845–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bird A. J., Gordon M., Eide D. J., Winge D. R. (2006) Repression of ADH1 and ADH3 during zinc deficiency by Zap1-induced intergenic RNA transcripts. EMBO J. 25, 5726–5734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bird A. J., Blankman E., Stillman D. J., Eide D. J., Winge D. R. (2004) The Zap1 transcriptional activator also acts as a repressor by binding downstream of the TATA box in ZRT2. EMBO J. 23, 1123–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sinclair S. A., Krämer U. (2012) The zinc homeostasis network of land plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1553–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmer C. M., Guerinot M. L. (2009) Facing the challenges of copper, iron, and zinc homeostasis in plants. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 333–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assunção A. G., Herrero E., Lin Y. F., Huettel B., Talukdar S., Smaczniak C., Immink R. G., van Eldik M., Fiers M., Schat H., Aarts M. G. (2010) Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factors bZIP19 and bZIP23 regulate the adaptation to zinc deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10296–10301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heuchel R., Radtke F., Georgiev O., Stark G., Aguet M., Schaffner W. (1994) The transcription factor MTF-1 is essential for basal and heavy metal-induced metallothionein gene expression. EMBO J. 13, 2870–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langmade S. J., Ravindra R., Daniels P. J., Andrews G. K. (2000) The transcription factor MTF-1 mediates metal regulation of the mouse ZnT1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34803–34809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lichten L. A., Ryu M. S., Guo L., Embury J., Cousins R. J. (2011) MTF-1-mediated repression of the zinc transporter Zip10 is alleviated by zinc restriction. PLoS ONE 6, e21526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng D., Feeney G. P., Kille P., Hogstrand C. (2008) Regulation of ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters in zebrafish gill. Zinc repression of ZIP10 transcription by an intronic MRE cluster. Physiol. Genomics 34, 205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stoytcheva Z. R., Vladimirov V., Douet V., Stoychev I., Berry M. J. (2010) Metal transcription factor-1 regulation via MREs in the transcribed regions of selenoprotein H and other metal-responsive genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800, 416–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y., Kimura T., Huyck R. W., Laity J. H., Andrews G. K. (2008) Zinc-induced formation of a coactivator complex containing the zinc-sensing transcription factor MTF-1, p300/CBP, and Sp1. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 4275–4284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jackson K. A., Helston R. M., McKay J. A., O'Neill E. D., Mathers J. C., Ford D. (2007) Splice variants of the human zinc transporter ZnT5 (SLC30A5) are differentially localized and regulated by zinc through transcription and mRNA stability. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10423–10431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liuzzi J. P., Guo L., Chang S. M., Cousins R. J. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G517–G523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quandt K., Frech K., Karas H., Wingender E., Werner T. (1995) MatInd and MatInspector. New fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 4878–4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kambe T., Narita H., Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Hirose J., Amano T., Sugiura N., Sasaki R., Mori K., Iwanaga T., Nagao M. (2002) Cloning and characterization of a novel mammalian zinc transporter, zinc transporter 5, abundantly expressed in pancreatic β cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19049–19055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishihara K., Yamazaki T., Ishida Y., Suzuki T., Oda K., Nagao M., Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Kambe T. (2006) Zinc transport complexes contribute to the homeostatic maintenance of secretory pathway function in vertebrate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17743–17750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suzuki T., Ishihara K., Migaki H., Matsuura W., Kohda A., Okumura K., Nagao M., Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Kambe T. (2005) Zinc transporters, ZnT5 and ZnT7, are required for the activation of alkaline phosphatases, zinc-requiring enzymes that are glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cragg R. A., Christie G. R., Phillips S. R., Russi R. M., Küry S., Mathers J. C., Taylor P. M., Ford D. (2002) A novel zinc-regulated human zinc transporter, hZTL1, is localized to the enterocyte apical membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22789–22797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thornton J. K., Taylor K. M., Ford D., Valentine R. A. (2011) Differential subcellular localization of the splice variants of the zinc transporter ZnT5 is dictated by the different C-terminal regions. PLoS ONE 6, e23878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valentine R. A., Jackson K. A., Christie G. R., Mathers J. C., Taylor P. M., Ford D. (2007) ZnT5 variant B is a bidirectional zinc transporter and mediates zinc uptake in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14389–14393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cragg R. A., Phillips S. R., Piper J. M., Varma J. S., Campbell F. C., Mathers J. C., Ford D. (2005) Homeostatic regulation of zinc transporters in the human small intestine by dietary zinc supplementation. Gut 54, 469–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Helston R. M., Phillips S. R., McKay J. A., Jackson K. A., Mathers J. C., Ford D. (2007) Zinc transporters in the mouse placenta show a coordinated regulatory response to changes in dietary zinc intake. Placenta 28, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haas C. E., Rodionov D. A., Kropat J., Malasarn D., Merchant S. S., de Crécy-Lagard V. (2009) A subset of the diverse COG0523 family of putative metal chaperones is linked to zinc homeostasis in all kingdoms of life. BMC Genomics 10, 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bosomworth H. J., Thornton J. K., Coneyworth L. J., Ford D., Valentine R. A. (2012) Efflux function, tissue-specific expression and intracellular trafficking of the zinc transporter ZnT10 indicate roles in adult zinc homeostasis. Metallomics 4, 771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dufner-Beattie J., Kuo Y. M., Gitschier J., Andrews G. K. (2004) The adaptive response to dietary zinc in mice involves the differential cellular localization and zinc regulation of the zinc transporters ZIP4 and ZIP5. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49082–49090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wong A., Vallender E. J., Heretis K., Ilkin Y., Lahn B. T., Martin C. L., Ledbetter D. H. (2004) Diverse fates of paralogs following segmental duplication of telomeric genes. Genomics 84, 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crouzet J., Levy-Schil S., Cameron B., Cauchois L., Rigault S., Rouyez M. C., Blanche F., Debussche L., Thibaut D. (1991) Nucleotide sequence and genetic analysis of a 13.1-kilobase pair Pseudomonas denitrificans DNA fragment containing five cob genes and identification of structural genes encoding Cob(I)alamin adenosyltransferase, cobyric acid synthase, and bifunctional cobinamide kinase-cobinamide phosphate guanylyltransferase. J. Bacteriol. 173, 6074–6087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zambelli B., Danielli A., Romagnoli S., Neyroz P., Ciurli S., Scarlato V. (2008) High-affinity Ni2+ binding selectively promotes binding of Helicobacter pylori NikR to its target urease promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 383, 1129–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leipe D. D., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2002) Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 41–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mendel R. R., Smith A. G., Marquet A., Warren M. J. (2007) Metal and cofactor insertion. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Izumi Y., Auberson Y. P., Zorumski C. F. (2006) Zinc modulates bidirectional hippocampal plasticity by effects on NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 26, 7181–7188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chowanadisai W., Kelleher S. L., Lönnerdal B. (2005) Maternal zinc deficiency reduces NMDA receptor expression in neonatal rat brain, which persists into early adulthood. J. Neurochem. 94, 510–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kitamura H., Morikawa H., Kamon H., Iguchi M., Hojyo S., Fukada T., Yamashita S., Kaisho T., Akira S., Murakami M., Hirano T. (2006) Toll-like receptor-mediated regulation of zinc homeostasis influences dendritic cell function. Nat. Immunol. 7, 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Radtke F., Hug M., Georgiev O., Matsuo K., Schaffner W. (1996) Differential sensitivity of zinc finger transcription factors MTF-1, Sp1, and Krox-20 to CpG methylation of their binding sites. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 377, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ford D., Ions L. J., Alatawi F., Wakeling L. A. (2011) The potential role of epigenetic responses to diet in ageing. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 70, 374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]