Abstract

The distribution of T-type Ca2+ channels along the entire somatodendritic axis of sensory thalamocortical (TC) neurons permits regenerative propagation of low threshold spikes (LTS) accompanied by global dendritic Ca2+ influx. Furthermore, T-type Ca2+ channels play an integral role in low frequency oscillatory activity (<1–4 Hz) that is a defining feature of TC neurons. Nonetheless, the dynamics of T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent dendritic Ca2+ signalling during slow sleep-associated oscillations remains unknown. Here we demonstrate using patch clamp recording and two-photon Ca2+ imaging of dendrites from cat TC neurons undergoing spontaneous slow oscillatory activity that somatically recorded δ (1–4 Hz) and slow (<1 Hz) oscillations are associated with rhythmic and sustained global oscillations in dendritic Ca2+. In addition, our data reveal the presence of LTS-dependent Ca2+ transients (Δ[Ca2+]) in dendritic spine-like structures on proximal TC neuron dendrites during slow (<1 Hz) oscillations whose amplitudes are similar to those observed in the dendritic shaft. We find that the amplitude of oscillation associated Δ[Ca2+] do not vary significantly with distance from the soma whereas the decay time constant (τdecay) of Δ[Ca2+] decreases significantly in more distal dendrites. Furthermore, τdecay of dendritic Δ[Ca2+] increases significantly as oscillation frequency decreases from δ to slow frequencies where pronounced depolarised UP states are observed. Such rhythmic dendritic Ca2+ entry in TC neurons during sleep-related firing patterns could be an important factor in maintaining the oscillatory activity and associated biochemical signalling processes, such as synaptic downscaling, that occur in non-REM sleep.

Key points

Sensory thalamocortical (TC) neurons are thought to play a crucial role in oscillatory brain activity typical of slow wave sleep.

Intrinsic oscillations in TC neurons rely upon expression of T-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels.

We show that during sleep like firing patterns in TC neurons in brain slices, low threshold spikes mediated by T-type channels produce global and rhythmic dendritic Ca2+ signals. In particular we show Ca2+ elevations in dendritic spine like structures during slow oscillatory activity.

We find that the duration of dendritic Ca2+ signals and the mean level of Ca2+ in TC neuron dendrites varies with oscillation frequency.

This global repetitive Ca2+ entry in to TC cells during oscillations could have significant implications for synaptic signalling and biochemical processes in these important sensory neurons.

Introduction

The ability to generate and sustain low frequency (<1–4 Hz) T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent oscillatory activity is one of the hallmarks of sensory thalamocortical (TC) neurons (Leresche et al. 1991; Steriade et al. 1993, 1996; Contreras & Steriade, 1995; Hughes et al. 2002; Crunelli & Hughes 2010). Through a dynamic interaction between hyperpolarisation activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels that mediate the IH current and T-type Ca2+ currents (IT), TC neurons are capable of sustaining prolonged trains of rhythmic low threshold spikes (LTSs) at 1–4 Hz that are thought to contribute to the occurrence of δ waves in the EEG of humans and animals during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (Fig. 1D) (McCormick & Pape, 1990; Leresche et al. 1991). Furthermore, under the influence of corticofugal input (Timofeev & Steriade, 1996), particularly through activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR 1a) at corticothalamic (CT) synapses (Hughes et al. 2002), TC neurons can display a prominent pattern of repeating depolarised ‘UP’ and hyperpolarised ‘DOWN’ states that occur at frequencies <1 Hz and are known as the slow oscillation. This intrinsic slow oscillatory capacity has been demonstrated to derive from a bistable interaction between the window component of IT (ITWIN) and a leak K+ current (IKLEAK) along with notable contributions from a Ca2+ activated non-specific cation current (ICAN) and IH (Fig. 1D) (Hughes et al. 2002; Dreyfus et al. 2010). On the basis of increasing evidence, the TC neuron slow oscillation combined with analogous rhythmic activity in thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) neurons has been postulated to play a significant role in the generation and maintenance of EEG slow waves during NREM sleep (Crunelli & Hughes 2010; Ushimaru et al. 2012).

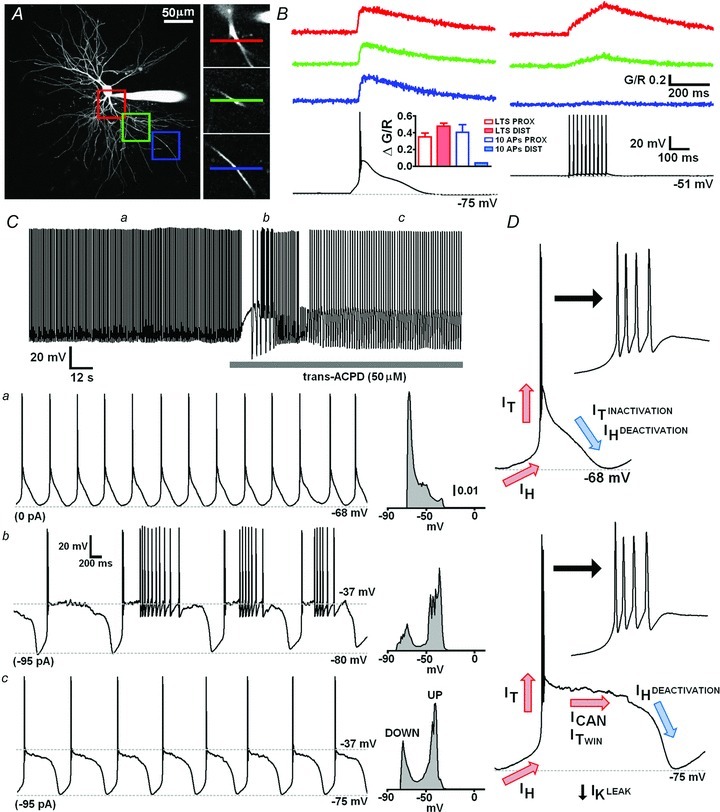

Figure 1. State-dependent spatial differences in dendritic Ca2+ signalling in cat MGB neurons and intrinsic T-type Ca2+ channel dependent oscillatory activity.

A, maximum intensity projection of a typical cat MGB neuron illustrating the dendritic sites where linescans (500 Hz) depicted in B were performed. Proximal, medial and distal regions (50 × 50 μm) are colour coded red, green and blue respectively and are shown enlarged (right). Coloured lines show precise locations of linescans. B, dendritic Δ[Ca2+] evoked by LTS and 10 action potentials at 50 Hz at each location depicted in A. Inset summarises the mean Δ[Ca2+] evoked by LTS (red) or action potentials (blue) at either proximal (<60 μm, open bars) or distal (>60 μm, filled bars) dendritic locations (n = 2–3). Ca, a typical MGB TC neuron showing spontaneous oscillatory activity at δ (1–4 Hz) frequency. All points histogram shows the distribution of membrane potentials over a 10 s period (1 mV bin size). Application of 50 μm trans-ACPD produced a large depolarisation which resulted in the emergence of a slow (< 1 Hz) oscillation of the membrane potential between depolarised UP states and hyperpolarised DOWN states when a small amount (−95 pA) of current was injected into the soma. b, expanded trace showing several cycles of the slow oscillation with action potential firing on the UP state that occurred immediately after ACPD application. c, expanded trace showing several ‘quiescent’ cycles of the slow oscillation lacking firing in the UP state. D, illustration of the proposed ionic mechanisms underpinning the intrinsic δ and slow oscillatory capacity of TC neurons.

Recently, we demonstrated that T-type Ca2+ channels are distributed throughout the dendritic arbour of TC neurons in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and that electrically and synaptically evoked LTS, characteristic of sleep-related firing patterns, propagate actively along dendrites resulting in global Ca2+ influx (Errington et al. 2010). This LTS-evoked Ca2+ influx into distal TC neuron dendrites could have a significant impact at CT synapses since these inputs form up to 50% of synapses onto TC neurons, are distributed across intermediate and distal dendritic regions and are strongly and repetitively activated during slow oscillations. Thus, LTS evoked Ca2+ influx represents an ideal feedback mechanism for postsynaptic control of modulatory CT inputs. However, the ability of TC neurons to sustain global Ca2+ influx during intrinsic spontaneous rhythmic activity and the dynamics of such Ca2+ signals remain unknown. Therefore, we have chosen to investigate the dynamics of dendritic Ca2+ signalling in TC neurons during T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent slow oscillatory activity using two-photon Ca2+ imaging in cat thalamic slices. We find that during both δ and slow (<1 Hz) oscillations, TC neuron dendrites can sustain global oscillatory Ca2+ influx and that the decay time constant of Ca2+ transients (Δ[Ca2+]) is dependent upon dendritic location and oscillation frequency.

Methods

Electrophysiology

Parasagittal slices of the thalamus including the medial geniculate body (MGB) were prepared from the brains of 6- to 8-week-old cats, which were removed by wide craniotomy after the animals were deeply anaesthetised using isoflurane as previously described (Hughes et al. 2002). All experiments were performed in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) act 1986, UK and after approval by the Cardiff University Research Ethics Committee. Slices were stored for 1 h at 35°C in sucrose containing solution and then maintained at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) (mm: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, 305 mosmol l−1) and used within 10–12 h. For recording, slices were transferred to a submersion chamber continuously perfused with warmed (33–34 °C) aCSF (mm: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, 305 mosmol l−1) at a flow rate of 2–2.5 ml min−1. Somatic whole-cell current clamp recordings were performed on MGB TC neurons using pipettes with resistances of 2–5 MΩ when filled with internal solution containing (mm) 115 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 2 Mg-ATP, 2 Na-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, 10 sodium phosphocreatine, 10 Hepes (pH 7.3, 290 mosmol l−1) supplemented with 50 μm Alexa Fluor 594 and 200 μm Fluo 5F for Ca2+ imaging. Electrophysiological data were acquired at 20 kHz and filtered at 6 kHz using a Multiclamp 700B patch clamp amplifier and pCLAMP 10.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Series resistance at the start of experiments was between 11 and 15 MΩ and varied ≤30% during recordings.

Imaging

Two photon laser scanning microscopy (2P-LSM) was performed using a Prairie Ultima (Prairie Technologies, Madison, WI, USA) microscope powered by a Ti:sapphire pulsed laser (Chameleon Ultra II, Coherent, Coherent, Ely, UK) tuned to λ = 1000 nm as previously described (Errington et al. 2010). Dendritic fluorescence signals were recorded by performing linescans (500 Hz, Fig. 1B) across dendrites at selected regions of interest (ROI) (0.042 μm per pixel, 7.2 μs pixel dwell time) or by performing frame scans of selected ROIs during epochs of oscillatory activity (10 × 10 μm, 15 × 15 pixels at 100 frames per second (fps) for 20 s). During prolonged frame scanning laser power was minimised to prevent photodamage. For calculation of distance-dependent changes in intracellular Ca2+ (ΔCa2+), dendrites were selected that were limited to a narrow optical plane (≤20 μm Z variance). Distances were approximated by measuring along the dendrite from the somatic centre to the dendritic ROI on a two-dimensional maximum intensity projection of each neuron (Fig. 1A). Maximum intensity projections were constructed from Z series of 120–150 images (512 pixels, 0.66 μm per pixel) taken with 1 μm focal steps. To measure the amplitude of dendritic Δ[Ca2+], ΔG/R was determined by subtracting baseline G/R values (50 ms period before stimulus) from the peak G/R signal (20–50 ms interval). To estimate indicator saturation for Fluo 5F, we measured G/Rmax (1.2) in 2 mm Ca2+ and G/Rmin (0.2) in 2 mm EGTA in a patch pipette in our microscope. During experiments typical ΔG/Rsignals were ∼0.3 and G/Rrest was 0.3 resulting in nonlinearity errors [ΔG/Rsignals/(ΔG/Rmax–ΔG/Rrest)] of ≤33%. We also measured saturation in situ in proximal dendrites by evoking 1 s trains of action potentials at 150 and 200 Hz and found this to be G/R = 1.1. Thus during our experiments Δ[Ca2+] did not come close to saturating the Ca2+ indicator. Analysis was performed offline using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). Decay time contants (τdecay) were measured by fitting mono-exponentials (Prizm 5, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) to the decay phase of Δ[Ca2+] with fits constrained by peak G/R. All data are presented as mean ± SEM and statistical tests were performed using Prizm 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, Ca, USA) and are described where appropriate in the text. Differences in data were deemed to be significant when P < 0.05.

Results

In rat dLGN, evoked LTS propagate actively throughout the dendritic tree of TC neurons resulting in global Δ[Ca2+] whereas single or relatively brief (up to 700 ms) evoked trains of action potentials produce Δ[Ca2+] at only proximal locations (Errington et al. 2010). In order to test if this property is common to sensory TC neurons across nuclei and species, we first characterised dendritic Δ[Ca2+] evoked by LTS and tonic action potential firing in cat MGB. Similar to our previous findings, we found that LTS, evoked by small somatic current injections (100–160 pA, 50 ms) from hyperpolarised potentials (∼−75 mV), produced dendritic Δ[Ca2+] throughout the dendritic arbor of MGB neurons (Fig. 1A and B). In these neurons, distal (>100 μm) LTS-evoked (ΔG/R: 0.48 ± 0.04, n = 3) Δ[Ca2+] were not significantly (P > 0.05, paired t test) different from those observed in proximal dendrites (ΔG/R: 0.35 ± 0.05, n = 3). In contrast, dendritic Δ[Ca2+] evoked by trains of 10 action potentials at 50 Hz (0.8–1.5 nA, 2 ms) when the same neurons were depolarised to approximately −50 mV by DC injection were restricted to proximal dendrites (ΔG/R: 0.40 ± 0.1, n = 3) without significant Ca2+ accumulation at distal locations (ΔG/R: 0.04, n = 2). Therefore, these findings suggest that differences in intrinsic dendritic Δ[Ca2+] signalling during behavioural state-dependent tonic and burst firing modes are common to sensory TC neurons of different thalamic nuclei (i.e. dLGN and MGB) and across different species (i.e. rat and cat).

It has been previously demonstrated in slices of cat thalamus in vitro that thalamic neurons undergo intrinsic oscillatory activity at both δ and slow (<1 Hz) frequencies (Hughes et al. 2002; Blethyn et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2006) that is almost indistinguishable from firing patterns observed in these neurons in vivo. However, these previous studies were conducted using sharp electrode recording techniques in interface style recording chambers that are inaccessible to two-photon imaging which typically requires the use of high numerical aperture water immersion objective lenses. We therefore performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings in a submersion chamber (bath volume ∼2–3 ml) that allowed us to concurrently image dendritic Ca2+ signalling. Under these conditions we found that upon ‘break-in’ of the patch recording, 57% (9/16) of MGB TC neurons exhibited spontaneous δ frequency (1.38 ± 0.06 Hz, n = 9) activity consisting of repetitive T-type Ca2+ channel mediated LTS (Hughes et al. 2002; Dreyfus et al. 2010) crowned with three to six action potentials (Fig. 1C and D). These oscillations were robust and continued throughout the duration of the experiments (> 1 h including dye loading time) with little variation in frequency (Fig. 1C). Bath application of the group I/II mGluR agonist trans-(1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD; 50 μm) depolarised TC neurons (87.5%, 7/8 tested) (Fig. 1C) and upon somatic injection of hyperpolarising current (−40 to –220 pA DC) caused them to exhibit a slow oscillation (0.35 ± 0.05 Hz, n = 7) of their membrane potential between depolarised UP states (−44 ± 3.5 mV, n = 7) and hyperpolarised DOWN states (−78.5 ± 2 mV, n = 7) (Fig. 1C). The difference between peaks of this bimodal distribution of membrane potential (Fig. 1C), which correspond to UP and DOWN states respectively, was slightly greater than that observed in previous recordings using sharp microelectrodes although other features, including the characteristic inflection point that marks the transition from UP to DOWN states and the LTS that marks the DOWN to UP state transition, were qualitatively similar (Hughes et al. 2002). Slow oscillations consisted of either ‘active’ oscillations where tonic action potential firing was observed on the UP state of the oscillation (Fig. 1Cb) or ‘quiescent’ oscillations where tonic firing was absent (Fig. 1Cc). For the Ca2+ imaging experiments described here DC current injection was adjusted to achieve only quiescent oscillations, though in a few cases Δ[Ca2+] were also recorded during ‘active’ slow oscillation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

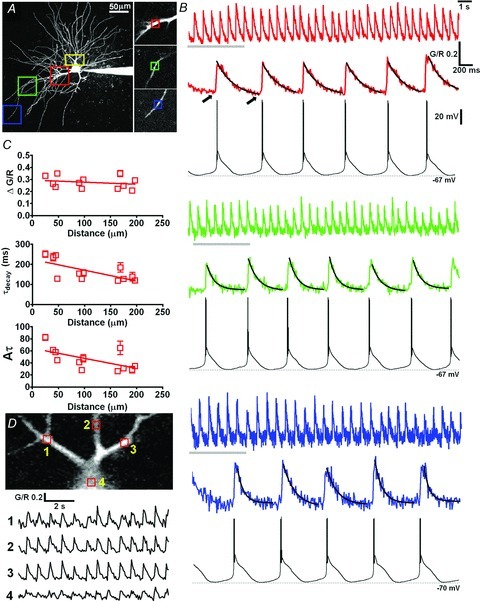

By imaging 10 μm2 ROIs along the length of MGB TC neuron dendrites (Fig. 2A) (n = 12 dendritic locations on 6 neurons, i.e. 12/6) at 100 fps for 20 s during spontaneous δ oscillations, we observed global dendritic oscillations in Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 2B). The peak amplitudes (A) of dendritic Δ[Ca2+] during δ oscillations (Δ[Ca2+]δ) were not dependent upon distance from the soma (P > 0.05, n = 12/6, Pearson's test) with ΔG/R values of 0.29 ± 0.03 (n = 4), 0.26 ± 0.02 (n = 3) and 0.26 ± 0.03(n = 5) for proximal (<60 μm), intermediate (60–120 μm) and distal (>120 μm) dendrites respectively. Imaging a larger area (54 × 32 μm, 15 fps) (Fig. 2A and D) of the proximal dendritic field revealed that Δ[Ca2+]δ occurred synchronously across multiple proximal dendrites (Supplementary Movie 1). Furthermore, the mean ‘resting’ level of Ca2+ (G/Rrest: 0.31 ± 0.01, n = 12 pooled dendritic locations) measured immediately prior to the onset of each LTS (20–50 ms, indicated by arrows in Fig. 2B) was not significantly different (P > 0.05, unpaired t test) from the resting level in dendrites of non-oscillating cells (G/Rrest: 0.27 ± 0.02, n = 7). This suggests that Ca2+ extrusion in dendrites during oscillations, at least up to 2 Hz, is sufficiently rapid to return the Ca2+ concentration to near resting levels between cycles. Under the conditions used in this study, we estimate using the incremental Ca2+ binding ratio (Neher & Augustine 1992; Errington et al. 2010) that our Ca2+ indicator adds an additional buffering capacity to the neuron of approximately KB∼165. Thus, the amplitudes of oscillations evoked Δ[Ca2+] are likely to be reduced and τdecay prolonged compared to those in the absence of exogenous buffers and it is therefore likely that unperturbed Δ[Ca2+]δ will have τdecay that are sufficiently small to allow Ca2+ oscillations from resting levels across the range of frequencies encompassing the entire δ band. We did not see strong evidence for summation of Δ[Ca2+]δ across the range of spontaneous oscillation frequencies recorded in these neurons. In a small number of cases during δ frequency activity some summation of transients in proximal dendrites may have occurred but comparison of our measurements of baseline G/R (measured as described above) (G/R 0.296 ± 0.010) with the plateau levels obtained from exponential fits (0.278 ± 0.009) revealed no significant difference (Student's unpaired t test, P = 0.2537).

Figure 2. Rhythmic dendritic Ca2+ oscillations during intrinsic δ-frequency activity in TC neurons.

A, maximal intensity projection illustrating the ROIs where scans illustrated in B were performed. Proximal, medial and distal regions (50 × 50 μm) are colour coded red, green and blue, respectively, and are shown enlarged (right). Small boxes indicate the 10 μm2 ROIs that were scanned at 100 fps. B, Δ[Ca2+] recorded in dendrites during spontaneous δ-frequency activity. Top traces show Δ[Ca2+] during the entire 20 s imaging trial and bottom traces depict expanded views of the Δ[Ca2+] indicated by the grey bars alongside the concurrently recorded somatic membrane potential oscillations. Black lines represent mono-exponential fits to the Δ[Ca2+] used to yield τdecay. C, graphs summarising the mean amplitude (ΔG/R), τdecay, and integral (Aτ) of Δ[Ca2+] as a product of distance from the soma for 13 dendritic locations from six MGB TC neurons. D, a larger region of interest (shown by the yellow box in A) that was scanned at 15 fps demonstrates that Δ[Ca2+] occur synchronously in a number of dendrites.

Dendritic Δ[Ca2+]δ evoked by four to seven oscillatory cycles were well fitted individually with single exponential functions to yield τdecay (Fig. 2B) (R2: <60 μm: 0.95 ± 0.002, n = 24 fits from 4 dendrites i.e. 24τ/4; 60–120 μm: 0.87 ± 0.0, n = 18τ/3; >120 μm: 0.84 ± 0.02, n = 29τ/5). We observed a negative correlation (P < 0.05, n = 12/6, Pearson's test) between τdecay and the distance of the dendritic imaging location from the soma with proximal Δ[Ca2+]δ decaying significantly (P < 0.001, One-way ANOVA Bonferroni's multiple comparison test) more slowly (<60 μm: 243.6 ± 14.6 ms, n = 24τ/4) than those in intermediate (60–120 μm: 145.6 ± 7.2 ms, n = 18τ/3) or distal dendrites (136.4 ± 7.9 ms, n = 29τ/5) (Fig. 2C). Thus, the relationship between the integral (Aτ) of Δ[Ca2+]δ and distance from the soma also showed a significant negative correlation (P < 0.05, n = 12, Pearson's test) with the area of distal Δ[Ca2+]δ being significantly smaller than proximal ones (Fig. 2B and C). However, an important experimental caveat that needs to be considered is the possibility that unequal distribution of added buffers (Ca2+-indicator) throughout the dendritic arbour could account for these observed differences in τdecay (Errington et al. 2010). The distance-dependent decrease in the Δ[Ca2+]δ integral Aτ, which is independent of added buffer concentration, suggests that despite this potential source of error total Ca2+ influx is reduced in distal dendrites compared to more proximal regions, not accounting for surface area to volume ratios.

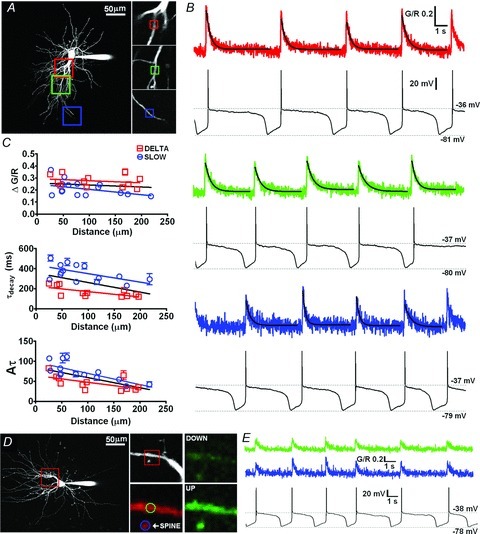

In the presence of trans-ACPD (50 μm), slow (<1 Hz) oscillations with characteristically pronounced UP states also produced Δ[Ca2+] throughout the dendritic tree (Δ[Ca2+]<1Hz). Δ[Ca2+]<1Hz onsets were synchronous with LTS that mark the DOWN to UP state transition of each cycle of the oscillation and, as for δ oscillations, their amplitudes did not show significant correlation (P > 0.05, n = 15/7, Pearson's test) with the distance of the dendritic imaging site from the soma (ΔG/R: <60 μm: 0.24 ± 0.02, n = 8; 60–120 μm: 0.21 ± 0.02, n = 5; >120 μm: 0.16 ± 0.01, n = 3; P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's multiple comparison test) (Fig. 3A–C). Furthermore, in three MGB neurons we were able to identify and image characteristic dendritic spines or thorny excrescences protruding from proximal dendrites that are typical of some cat TC neurons (Fig. 3D). We found that during slow oscillatory activity, Δ[Ca2+] observed in the proximal dendritic shaft were accompanied by increases in Ca2+ in thorny excresences that were of a similar amplitude (P > 0.05, n = 3, paired t test) (Fig. 3D and E). Similarly to spontaneous δ activity the resting or DOWN state concentration of dendritic Ca2+ in slowly oscillating cells was not significantly different from that measured in non-oscillating neurons (G/Rrest: 0.29 ± 0.01, P > 0.05, n = 15/7, unpaired t test). Moreover, as for δ activity evoked Δ[Ca2+], Δ[Ca2+]<1 Hz had τdecay that were slower in proximal dendrites (409.0 ± 18.2 ms, P < 0.001, unpaired t test, n = 26τ/7) compared with distal locations (284.7 ± 21.1 ms, n = 13τ/3) (Fig. 3B and C). A significant negative correlation was found between both τdecay (P < 0.05, n = 15/7, Pearson's test) and Aτ (P < 0.01, n = 15/7, Pearson's test) with increasing distance from the soma for Δ[Ca2+]<1 Hz (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Rhythmic dendritic Ca2+ oscillations during trans-ACPD evoked slow (<1 Hz) oscillations in TC neurons.

A, maximal intensity projection illustrating the ROIs where scans illustrated in B were performed. Proximal, medial and distal regions (50 × 50 μm) are colour coded red, green and blue, respectively, and are shown enlarged (right). Small boxes indicate the 10 μm2 ROI that were scanned at 100 fps. B, 20 s epochs of slow oscillatory activity (0.2–0.25 Hz) and their corresponding dendritic Δ[Ca2+]. Black lines represent mono-exponential fits to the data. C, graphs summarising the mean amplitude (ΔG/R), τdecay, and integral (Aτ) of slow oscillation Δ[Ca2+] against distance from the soma for 15 dendritic locations from 7 MGB TC neurons (blue circles). Data for δ activity are also shown for comparison (red squares). Red and blue lines are linear regression fits to slow and δ data, respectively, and the black line represents a fit to the pooled data. D, Δ[Ca2+] in dendritic thorny excrescences during slow oscillations. Maximal intensity projection illustrating the ROI where scans illustrated in B were performed. The enlargement (right) shows the dendrite from the area indicated in A where the spiny appendage was observed. The regions of interested depicted with blue and green circles, respectively, show the areas on the dendrite and spine over which the fluorescence signals were integrated to obtain the data shown in B. The green images show the increase in Ca2+-dependent fluorescence intensity of Fluo-5F at the peak of the UP state compared to the DOWN state. E, traces show similar Δ[Ca2+] occurring simultaneously in both the thorny excrescence and parent dendrite during several cycles of slow oscillatory activity (∼0.3 Hz).

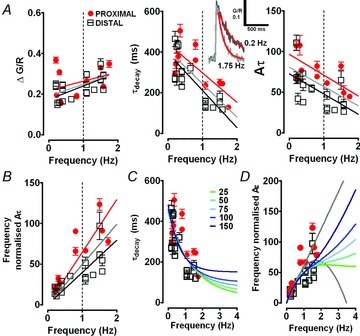

When Δ[Ca2+]δ and Δ[Ca2+]<1 Hz data were pooled, a significant negative correlation between τdecay and oscillation frequency was observed for Δ[Ca2+] measured in either proximal (<60 μm from the soma, >3 μm diameter, P < 0.05, n = 10, Pearson's test) or distal (>60 μm from the soma, <3 μm diameter, P < 0.01, n = 17, Pearson's test) (Fig. 4A) dendrites. The relationship between the mean oscillation evoked dendritic Ca2+ level, which is unaffected by the addition of exogenous buffer (i.e. the integral Aτ multiplied by the frequency, [Ca2+]mean) could be well fitted by linear regression (across the range of oscillation frequencies we tested in this study) and there was positive correlation (P < 0.001, Pearson's test) between [Ca2+]mean and oscillation frequency (Fig. 4B). However, for a truly linear relationship to exist between these two parameters, Aτ would be required to remain constant as frequency varied and as can be seen in Fig. 4A this is clearly not the case. If the decrease in Aτ was linear due to a lack of change in A (Fig. 4A), but a linear decrease in τdecay as appears to be the case across the range of oscillation frequencies examined (Fig. 4A), then the relationship between [Ca2+]mean and frequency would be parabolic (Fig. 4D). However, this appears to suggest that τdecay of Δ[Ca2+] would approach zero at around 3 Hz implying a failure of T-type channel mediated Ca2+ influx and presumably termination of oscillatory activity. A more likely situation is that τdecay decreases in a pseudo-exponential fashion as oscillation frequency increases but reaches a plateau level within the δ frequency band. By fitting our τdecay versus frequency data with mono-exponential functions constrained to differing plateau levels (25–150 ms, Fig. 4C), we were able to model dendritic [Ca2+]mean that might arise from this assumption (Fig. 4D). However, without further data at frequencies between 2 and 4 Hz, which we could not obtain in vitro, we are limited to the conclusion that the relationship between dendritic [Ca2+]mean and oscillation frequency falls between the linear and parabolic approximations.

Figure 4. Frequency dependent changes in dendritic calcium transients during rhythmic activity in TC neurons.

A, graphs summarising peak Δ[Ca2+] amplitude (δG/R), τdecay, and Aτ and frequency normalised Aτ ([Ca2+]mean) against oscillation frequency for proximal (red circles) and distal (black squares) dendrites. Red and black lines represent linear regression fits to the data for proximal and distal dendrites, respectively, and grey line represents a fit to the pooled data. The inset shows two typical Δ[Ca2+] from proximal dendrites of neurons oscillating at slow and δ frequency. Red lines are mono-exponential fits to the data. B, frequency normalised Aτ ([Ca2+]mean) plotted against against frequency. C and D, red circles and black squares show the data from experiments whilst grey lines represent modelled fits based upon constant and linearly decreasing values of Aτ. Coloured lines represent modelled fits based on Aτ calculated with mono-exponentially decreasing τdecay values constrained to varying plateau levels (25–150 ms).

Discussion

Using two-photon Ca2+ imaging of cat MGB TC neuron dendrites in vitro we have shown for the first time that low frequency oscillatory activity typical of non-REM sleep states is associated with rhythmic and global oscillations in dendritic Ca2+ concentration. Unlike previous findings based upon evoked Ca2+ signals (Crandall et al. 2010; Errington et al. 2010), our new data demonstrates that TC neuron dendrites experience rhythmic spikes in Ca2+ concentration during spontaneous intrinsicδ frequency and slow oscillations. Moreover, we demonstrate that dendritic Ca2+ clearance is sufficiently rapid to permit sustained oscillations in Ca2+ concentration as the peak amplitudes of spontaneously occuring Δ[Ca2+] do not exceed those of single bursts (i.e. no summation) whilst their τdecay correlate negatively with both dendritic distance from the soma and oscillation frequency. This pattern of oscillating Ca2+ concentrations rather than cumulative Ca2+ build up through summation of transients, as observed following electrically elicited LTSs (Budde et al. 2000), could have a significant effect upon Ca2+-dependent signalling processes. It is likely that the increased τdecay of Δ[Ca2+]<1 Hz (compared to Δ[Ca2+]δ) reflects slowed inactivation/deactivation of T-type channels and/or the presence of ITWIN during depolarised UP states, slow Ca2+ influx through non-T-type channel sources such as ICAN or reduced activity of Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms such as plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases (PMCAs) or Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCXs). Furthermore, we demonstrate that during slow (<1 Hz) oscillations LTS-mediated Ca2+ signals are detected in dendritic thorny excrescences that are thought to be the major target for synaptic input from sensory axons (Sherman & Guillery, 1996). To our knowledge this is the first demonstration of LTS or oscillation evoked Ca2+ signalling in these dendritic appendages in TC neurons.

Whilst the dendritic distribution of T-type channels (Destexhe et al. 1998; Williams & Stuart, 2000; Errington et al. 2010) in TC neurons may be necessary for optimising the threshold for LTS initiation allowing interaction with Ih and generation and maintenance of oscillatory activity, the biochemical consequences of global rhythmic dendritic Ca2+ entry during slow oscillations remain unclear. It appears that a major function of thalamocortical slow and δ oscillations is to provide excitatory input to the neocortex and perhaps to initiate cortical DOWN to UP state transitions (Crunelli & Hughes, 2010; Ushimaru et al. 2012). It is therefore, conceivable that TC neuron dendritic Ca2+ oscillations simply represent a secondary consequence of the channel distribution that is required to achieve this without necessarily having a significant biochemical signalling role. However, signalling roles for T-type channel mediated Ca2+ influx have already been established including cAMP-dependent upregulation of Ih currents (Luthi & McCormick, 1998, 1999) that are thought to contribute to termination of spindle oscillations in corticothalamic circuits. Given the widespread dendritic expression of T-type channels (Errington et al. 2010), it appears likely that such processes are occurring predominantly within dendrites. Indeed, due to the significantly larger surface area to volume ratio (SAVR) of thin dendrites in comparison to the soma, dendritic expression of T-type channels could result in significantly larger local Ca2+ accumulations than in the soma for uniform levels of T conductance. Thus, placement of T-type channels in dendrites makes them ideal candidates to provide a source of Ca2+ to plastic postsynaptic processes occurring in TC neurons. Furthermore, the greater SAVR of dendrites may also allow more efficient expression and function of PMCAs and NCXs thus contributing to rapid and robust Ca2+ clearance and the ability to sustain Ca2+ oscillations such as those we have observed. In fact, because Ca2+ extrusion is an active process requiring ATP expenditure, this strategy would be metabolically beneficial to TC neurons and could potentially minimise the energy cost of firing LTS especially during rhythmic activities. This would be invaluable if slow and δ frequency oscillations in thalamocortical neurons play a prominent role in generating or sustaining prolonged slow EEG rhythms of NREM sleep as has been suggested (Crunelli & Hughes 2010; Ushimaru et al. 2012).

It has been proposed recently that a major functional role of slow oscillations in cortical networks is homeostatic synaptic plasticity. In particular, it has been suggested that plastic processes during wakefulness are biased towards synaptic potentiation and that slow oscillations play an active role in rebalancing circuits by downscaling synaptic strength and thus optimising network efficiency (Tononi & Cirelli, 2006; Bushey et al. 2011). It is tempting to speculate that sleep-associated Ca2+ oscillations in TC neuron dendrites could perform a similar role by downscaling synaptic strength in these neurons. For example, rhythmic LTS associated dendritic Ca2+ signalling would be ideally suited to downscale the strength of corticothalamic synapses, which numerically dominate input to TC neurons, are distributed primarily on distal dendrites and are repetitively activated during slow wave activity. Such a mechanism could operate in response to synaptic potentiation that has occurred during previous wakefulness or as a measure to prevent unwanted or unnecessary increases in synaptic strength resulting from corticofugal inputs during non-REM sleep.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grants 91882 (V.C.), 78311 (S.W.H.) and a Wellcome Trust V.I.P. award (A.C.E.). We thank Dr Magor Lórincz for assistance in slice preparation.

Glossary

- dLGN

dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus

- HCN

hyperpolarisation activated cyclic nucleotide gated channel

- LTS

low threshold spike

- MGB

medial geniculate body

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- ROI

region of interest

- TRN

thalamic reticular nucleus

- Δ[Ca2+]

Ca2+ transient

Author contibutions

A.C.E., S.W.H. and V.C. conceived the experiments. A.C.E. designed and performed the experiments, analysed data and wrote the article. S.W.H. and V.C. critically revised the article.

Author's present address

S. W. Hughes: Eli Lilly UK, Erl Wood Manor, Windlesham, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplemental Figure S1

Supplemental Movie S1

References

- Blethyn KL, Hughes SW, Tóth TI, Cope DW, Crunelli V. Neuronal basis of the slow (<1 Hz) oscillation in neurons of the nucleus reticularis thalami in vitro. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2474–2486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3607-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde T, Sieg F, Braunewell K-H, Gundelfinger E, Pape H-C. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release supports the relay mode of activity in thalamocortical cells. Neuron. 2000;26:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey D, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: structural evidence in Drosophila. Science. 2011;332:1576–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1202839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus FM, Tscherter A, Errington AC, Renger JJ, Shin HS, Uebele VN, Crunelli V, Lambert RC, Leresche N. Selective T-type calcium channel block in thalamic neurons reveals channel redundancy and physiological impact of ITwindow. J Neurosci. 2010;30:99–109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4305-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Steriade M. Cellular basis of EEG slow rhythms: a study of dynamic corticothalamic relationships. J Neurosci. 1995;15:604–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00604.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall SR, Govindaiah G, Cox CL. Low-threshold Ca2+ current amplifies distal dendritic signalling in thalamic reticular neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15419–15429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3636-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelli V, Hughes SW. The slow (<1 Hz) rhythm of non-REM sleep: a dialogue between three cardinal oscillators. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nn.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Neubig M, Ulrich D, Huguenard J. Dendritic low-threshold calcium currents in thalamic relay cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3574–3588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03574.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington AC, Renger JJ, Uebele VN, Crunelli V. State-dependent firing determines intrinsic dendritic Ca2+ signalling in thalamocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14843–14853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2968-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SW, Cope DW, Blethyn KL, Crunelli V. Cellular mechanisms of the slow (<1 Hz) oscillation in thalamocortical neurons in vitro. Neuron. 2002;33:947–958. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leresche N, Lightowler S, Soltesz I, Jassik-Gerschenfeld D, Crunelli V. Low-frequency oscillatory activites intrinsic to rat and cat thalamocortical cells. J Physiol. 1991;315:155–174. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A, McCormick D. Periodicity of thalamic synchronized oscillations: the role of Ca2+ mediated upregulation of Ih. Neuron. 1998;20:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A, McCormick D. Modulation of a pacemaker current through Ca2+-induced stimulation of cAMP production. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:634–641. doi: 10.1038/10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape HC. Properties of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurons. J Physiol. 1990;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Augustine GJ. Calcium gradients and buffers in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1992;450:273–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. Functional organization of thalamocortical relays. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1367–1395. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Contreras D, Curró Dossi R, Nunez A. The slow (<1 Hz) oscillation in reticular thalamic and thalamocortical neurons: scenario of sleep rhythm generation in interacting thalamic and neocortical networks. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3284–3299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03284.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Contreras D, Amzica F, Timofeev I. Synchronization of fast (30–40 Hz) spontaneous oscillations in intrathalamic and thalamocortical networks. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2788–2808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02788.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timofeev I, Steriade M. Low-frequency rhythms in the thalamus of intact-cortex and decorticated cats. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:4152–4168. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushimaru M, Ueta Y, Kawaguchi Y. Differentiated participation of thalamocortical subnetworks in slow/spindle waves and desynchronization. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1730–1746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4883-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. Action potential backpropagation and somato-dendritic distribution of ion channels in thalamocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1307–1317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01307.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Blethyn KL, Cope DW, Tsomaia V, Crunelli V, Hughes SW. Nucleus- and species-specific properties of the slow (< 1Hz) sleep oscillation in thalamocortical neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;141(2):621–636. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.