Abstract

Synaptic plasticity of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) has been recently described in a number of brain regions and we have previously characterised LTP and LTD of glutamatergic NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs (NMDAR-EPSCs) in granule cells of dentate gyrus. The functional significance of NMDAR plasticity at perforant path synapses on hippocampal network activity depends on whether this is a common feature of perforant path synapses on all postsynaptic target cells or if this plasticity occurs only at synapses on principal cells. We recorded NMDAR-EPSCs at medial perforant path synapses on interneurons in dentate gyrus which had significantly slower decay kinetics compared to those recorded in granule cells. NMDAR pharmacology in interneurons was consistent with expression of both GluN2B- and GluN2D-containing receptors. In contrast to previously described high frequency stimulation-induced bidirectional plasticity of NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells, only LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs was induced in interneurons in our standard experimental conditions. In interneurons, LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs was associated with a loss of sensitivity to a GluN2D-selective antagonist and was inhibited by the actin stabilising agent, jasplakinolide. While LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs can be readily induced in granule cells, this form of plasticity was only observed in interneurons when extracellular calcium was increased above physiological concentrations during HFS or when PKC was directly activated by phorbol ester, suggesting that opposing forms of plasticity at inputs to interneurons and principal cells may act to regulate granule cell dendritic integration and processing.

Key points

NMDA receptors (NMDARs) activated by the neurotransmitter glutamate underlie certain forms of synaptic plasticity in the brain.

These receptors are also subject to plasticity and we have previously described both long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) of NMDARs in the principal granule cells of the dentate gyrus region of hippocampus.

The functional significance of these changes in NMDARs on hippocampal network activity depends on whether this occurs only on principal, excitatory neurons or if it also occurs on inhibitory interneurons.

Here we demonstrate differences in NMDAR subtype expression and plasticity in dendrite-targeting interneurons compared to granule cells.

Interneurons displayed LTD of NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission in response to perforant path activation and had a high threshold for induction of LTP of NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents, suggesting that opposing forms of plasticity at inputs to interneurons and principal cells may act to regulate granule cell dendritic integration and processing.

Introduction

Perforant path inputs to dentate gyrus form the main cortical input to hippocampus, and plasticity at perforant path synapses to granule cells has been extensively studied, including both NMDAR-dependent and NMDAR-independent forms of LTP and LTD of AMPA receptors (Wang et al. 1996, 1997a, b; Wu et al. 2001). Perforant path afferents also excite feedforward inhibitory interneurons, including subtypes which are located at the border between the hilus and granule cell layer and have dendrites projecting to the molecular layer (Han et al. 1993; Buckmaster & Schwartzkroin, 1995; Sik et al. 1997) and axons ramifying in the molecular layer where they synapse on granule cell dendrites.

Recent studies of synaptic plasticity in interneurons have shown both LTP and LTD of AMPA receptors in interneurons and the diversity that is characteristic of interneurons also extends to the mechanisms of plasticity in these cells (reviewed in Laezza & Dingledine, 2011). There are differences in AMPAR expression between principal cells and interneurons; for instance, GluA2-lacking calcium-permeable AMPARs have a role in NMDAR-independent LTP induction in interneurons (Maccaferri & McBain, 1996; Mahanty & Sah, 1998; Laezza & Dingledine, 2004; Lamsa et al. 2007; Galvan et al. 2008; Asrar et al. 2009; Galvan et al. 2010; Nissen et al. 2010; Sambandan et al. 2010). How NMDARs compare between principal cells and interneurons is not so clear and NMDAR-mediated EPSCs (NMDAR-EPSCs) in interneurons have been reported to have either similar (Sah et al. 1990) or faster (Perouansky & Yaari, 1993) decay kinetics. Both fast and slow NMDAR-mediated EPSPs have also been described in CA1 interneurons (Maccaferri & Dingledine, 2002) so it is likely that there is some heterogeneity in NMDAR expression between different subtypes.

Plasticity of NMDAR-EPSCs has increasingly been recognised in hippocampus (Bashir et al. 1991; Berretta et al. 1991; O’Connor et al. 1994; Morishita et al. 2005; Harney et al. 2006, 2008; Kwon & Castillo, 2008; Rebola et al. 2008) and other brain regions (Watt et al. 2004; Harnett et al. 2009). NMDAR plasticity in interneurons may have considerable influence on network activity, due to the central role of interneuron NMDARs in hippocampal gamma rhythm (Cunningham et al. 2006; Korotkova et al. 2010) and such plasticity of NMDARs in interneurons would, therefore, be predicted to alter such network activity. In agreement with this prediction, synaptic depression in interneurons has been linked to the generation of epileptiform bursts during gamma oscillations (Traub et al. 2005). It is important, therefore, to understand how plasticity at synaptic inputs to interneurons can influence dentate gyrus function and dysfunction.

Here we describe NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission at medial perforant path synapses on inhibitory interneurons compared to perforant path inputs to granule cells. Our findings identify distinct differences in NMDAR subunit composition and plasticity in interneurons compared to principal granule cells. As we have previously observed a role for GluN2D-containing NMDARs in LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells in dentate gyrus (Harney et al. 2008) and, because relatively strong expression of the GluN2D subunit has been noted in interneurons in dentate gyrus (Standaert et al. 1996), we investigated if expression of a specific NMDAR subtype had a role in NMDAR plasticity in interneurons. Our results demonstrate LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs at excitatory inputs to interneurons and a high threshold for induction of LTP using standard protocols, suggesting that strong perforant path activation results in reduced feedforward dendritic inhibition to granule cells.

Methods

Slice preparation and electrophysiology

Male Wistar rats (3–4 weeks old, 40–80 g) were anaesthetised with chloroform and killed by decapitation, in accordance with Trinity College Dublin Bioresources Ethical Committee guidelines and the guidelines of The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009). The brain was removed and transverse hippocampal slices (350 μm) were prepared in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mm): 75 sucrose, 87 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 10 d-glucose, 1 ascorbic acid and 3 pyruvic acid. During incubation and experiments slices were perfused with ACSF containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 25 d-glucose. Slices were maintained at 33°C for 1 h following dissection; all recordings were performed at physiological temperature (32–34 °C).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from hilar interneurons and granule cells of the dentate gyrus, visualized using an upright microscope (Olympus BX51 WI, Southend-on-Sea, UK) with infra-red differential interference contrast optics (IR-DIC). Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) and had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ when filled with intracellular solution containing (in mm): 130 CsMeSO4, 10 CsCl, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 20 phosphocreatine, 2 Mg2ATP, 0.3 NaGTP, 5 QX-314, 1 TEA (pH 7.3, 290–300 mosmol l−1). In experiments where BAPTA was substituted for EGTA, a modified intracellular solution was used which contained 90 mm CsMeSO4 and 40 mm BAPTA. For perforated patch clamp recordings, nystatin (100 μg ml−1) was added to the intracellular solution. Biocytin (0.1%) was included in the intracellular solution for visualization and histological identification of recorded interneurons.

Cells were voltage-clamped at −70 mV and, during a voltage step to −40 mV, EPSCs were evoked by stimulation with a bipolar tungsten wire electrode placed in the middle one-third of the dentate gyrus molecular layer to activate the medial perforant pathway. Control EPSCs were evoked at a test frequency of 0.033 Hz and had a short latency (<5 ms), consistent with monosynaptically evoked EPSCs. Series resistance ranged from 5–17 MΩ and was compensated by 50–80% (5 kHz bandwidth). HFS consisted of eight trains, each of eight stimuli at 200 Hz, inter-train interval of 2 s, repeated 3 times and delivered in current clamp mode. NMDAR-EPSCs were recorded in picrotoxin (100 μm), 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7 -sulphonamide disodium salt (NBQX, 10 μm), CGP55845 (2 μm) and d-serine (20 μm). Plasticity was measured from the average over 10 min at 40–50 min post-stimulation. Recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were filtered at 5 kHz using a 4-pole Bessel filter and were digitized at 10 kHz using a Digidata 1440 analog–digital interface (Molecular Devices).

All salts used were obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK). Picrotoxin, NBQX, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), PKC19−36 inhibitory peptide, carboxyeosin, nystatin, biocytin and cresyl violet were from Sigma, CGP55845 and (2S,2′R,3′R)-2-(2′,3′-Dicarboxycyclopro-pyl)glycine (DCG-IV) were from Tocris (Bristol, UK), ifenprodil, 2R*,3S*)-1-(phenanthrenyl-2-carbonyl) piperazine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid (PPDA) and (2R*,3S*)-1-(phenanthrenyl-3-carbonyl)piperazine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid (UBP141) were from Abcam Biochemicals (Cambridge, UK). Jasplakinolide was obtained from EMD Chemicals (Darmstadt, Germany).

Histological identification of interneurons

Slices were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Slices were resectioned at 80 μm and treated with an avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Biocytin-filled cells were visualized using cobalt-enhanced diaminobenzidine (Sigmafast DAB, Sigma). Slices were dehydrated and counterstained with cresyl violet. Stained cells were reconstructed using Neuromantic software (Darren Myatt, University of Reading, http://www.reading.ac.uk/neuromantic).

Data analysis

Data were acquired and analysed using pCLAMP 9.0, Clampfit (Molecular Devices) and Strathclyde Electrophysiology software (J. Dempster, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK). The decay phase of averaged NMDAR-EPSCs was fitted with one or two exponential functions and, for EPSCs best described by two exponentials, weighted decay time constants were calculated as τW = τ1[A1/(A1+A2)]+τ2[A2(A1+A2)], where τ is the fitted time constant and A is amplitude. Paired-pulse ratios for NMDAR-EPSCs were calculated using alternating single and paired-pulse stimuli and subtracting the averaged response to a single pulse from the average of the paired stimuli, to remove the postsynaptic current remaining after the first EPSC. Data are means ± SEM, and statistical significance was evaluated using Student's paired t test (P < 0.05) or one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's test. Correlations were evaluated using Pearson's correlation test. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test was used to test for a difference in the distributions of τw between granule cells and interneurons.

Results

NMDAR-EPSCs in dendrite-targeting interneurons – comparison with granule cells

NMDAR-mediated EPSCs were recorded from interneurons at the border of the hilus and the dentate gyrus granule cell layer and from granule cells in response to activation of the medial perforant pathway. During experiments interneurons were visually identified by the location of their somata in the subgranular region and were identified post hoc following histological processing. Twenty-four biocytin-filled interneurons which were recovered had dendrites projecting to the hilus and molecular layer with axons located in the molecular layer. A representative interneuron is illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Figure 1. Medial perforant path-evoked NMDAR-EPSCs recorded in interneurons have slow decay kinetics compared to those recorded in granule cells in dentate gyrus.

A, reconstruction of a representative interneuron, illustrating the location of the axon (shown in red) within the molecular layer. B, averaged EPSC traces recorded from a granule cell (red) and an inhibitory interneuron (black). C, histogram displaying the distributions of averaged weighted decay time constants in granule cells and interneurons. The distributions were fitted with a single Gaussian function. Superimposed lines illustrate the cumulative probability distributions for weighted decay time constants (τw) for granule cells (red) and interneurons (black). The distribution of time constants was significantly shifted toward slower values for interneurons; KS test, P < 0.001, n = 27 GCs and 58 INs. D, averaged weighted decay time constants for NMDAR-EPSCs recorded from granule cells and interneurons; *P < 0.001, n = 27 GCs and 58 INs. E, input resistance plotted against NMDAR-EPSC decay time constant showed no significant correlation for either interneurons (filled symbols) or granule cells (open symbols). F, 10–90% rise time plotted against τw was significantly correlated for granule cells (P = 0.01) but not for interneurons (P = 0.12). G, τw plotted against EPSC amplitude was not significantly correlated for granule cells (P = 0.56) but showed a significant negative correlation for interneurons (P = 0.002).

NMDAR-EPSCs recorded in interneurons had significantly slower kinetics compared to those recorded in granule cells, with a weighted decay time constant (τw) of 66 ± 4 ms in interneurons and 38 ± 2 ms in granule cells (Fig. 1B–D; unpaired t test, P < 0.001, n = 58 INs and 27 GCs) and a rise time of 6 ± 0.4 ms compared to 4 ± 0.2 ms in granule cells (P = 0.002). In addition, the distribution of decay time constants in interneurons (Fig. 1C, black line) was significantly shifted toward slower values compared to that for granule cells (Fig. 1C, red line; KS test, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in input resistance between interneurons and granule cells recorded from using a caesium-based intracellular solution (Rin = 172 ± 12 MΩ in interneurons, n = 58 and 182 ± 19 MΩ in granule cells, n = 27, P = 0.7). In addition, there was no significant correlation between input resistance and NMDAR-EPSC decay time constant in interneurons (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.18, P = 0.2, n = 57) or granule cells (r = 0.22, P = 0.4, n = 19; Fig. 1G). For granule cells, 10–90% rise time was significantly correlated with τw (r = 0.48, P = 0.01), but there was no significant correlation for interneurons (r = 0.21, P = 0.12; Fig. 1F). When τw was plotted against EPSC amplitude, there was no significant correlation for granule cells (r = 0.12, P = 0.56) in contrast to the significant negative correlation for interneurons (r = −0.43, P = 0.002; Fig. 1G). This suggests that synaptic currents recorded in interneurons may be subject to some electrotonic filtering although this was not significant for the faster rise time, which is predicted to be subject to greater distortion.

A presynaptic difference in transmission at synapses on interneurons and granule cells was also evident in different paired-pulse ratios (PPRs) recorded in the two cell types. Paired-pulse depression is characteristic of medial perforant path inputs to granule cells and in agreement, NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells had a PPR of 0.9 ± 0.02 (100 ms inter-stimulus interval, n = 4; Fig. 2A and C) while EPSCs in interneurons displayed paired-pulse facilitation with a PPR of 1.6 ± 0.15 (P < 0.001, unpaired t test vs. GC PPR, n = 21; Fig. 2B and C).

Figure 2. Different paired-pulse plasticity at medial perforant path synapses on granule cells and interneurons.

A, NMDAR-EPSCs recorded from a granule cell in response to single and paired-pulse stimulation (100 ms inter-stimulus interval) displaying paired pulse depression. B, NMDAR-EPSCs recorded from an interneuron in response to single and paired-pulse stimulation displaying paired pulse facilitation. The amplitude of the second EPSC was measured following subtraction of the averaged first EPSC evoked by a single stimulus, to remove the persisting postsynaptic current. C, bar graph showing paired pulse ratio for both cell types; *P < 0.001, unpaired t test, n = 4 GCs and 21 INs.

GluN2D subunits contribute to baseline NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons

To further examine the synaptic subtypes of NMDARs expressed in interneurons, we used the GluN2B-selective antagonist ifenprodil and the GluN2D-preferring antagonists PPDA and UBP141. All interneurons tested were sensitive to ifenprodil (3 μm) with depression of NMDAR-EPSC amplitude to 67 ± 7% of control (P = 0.02, n = 8; Fig. 3A, D and G). There were no changes in rise time (5 ± 0.3 ms in control and 5.2 ± 1 ms in ifenprodil, P = 0.4) or τw (59 ± 4 ms in control and 56 ± 7 ms in ifenprodil, P = 0.25). This is similar to our previous findings in granule cells, where ifenprodil depressed EPSC amplitude to 64% of control (Harney et al. 2008), suggesting a similar contribution of GluN2B-containing receptors at synapses on both cell types. We previously demonstrated that the GluN2D-selective antagonists PPDA and UBP141 had no effect on baseline synaptic NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells and only depressed NMDAR-mediated currents following inhibition of glutamate uptake or following induction of NMDAR-LTP (Harney et al. 2008). In contrast, both antagonists significantly depressed NMDAR-EPSC amplitude in interneurons. PPDA reduced NMDAR-EPSC amplitude to 72 ± 7% of control (P = 0.02, n = 6; Fig. 3C, F and G) with no change in rise time (7.3 ± 1 ms in control and 8.5 ± 1 ms in PPDA, P = 0.15) or τw (61 ± 9 ms in control and 64 ± 7 ms in PPDA, P = 0.2). Similarly, UBP141 depressed NMDAR-EPSC amplitude to 71 ± 4% of control (P = 0.005, n = 9; Fig. 3B, E and G) with no change in rise time (5 ± 0.6 ms in control and 6 ± 0.5 ms in UBP141, P = 0.07) or τw (66 ± 11 ms in control and 73 ± 10 ms in UBP141, P = 0.08). In agreement with previous findings, UBP141 had no effect on NMDAR-EPSCs recorded in granule cells in slices from the same animals (111 ± 11% of control, n = 3, data not shown). These results show that there is a contribution of GluN2D-containing receptors to synaptic NMDAR currents in interneurons but not in granule cells.

Figure 3. NMDAR-EPSCs in inhibitory interneurons are sensitive to GluN2B- and GluN2D-selective antagonists.

A, traces of averaged NMDAR-EPSCs displaying depression in the presence of the GluN2B-selective antagonist ifenprodil (3 μm). B and C, traces showing averaged NMDAR-EPSCs depressed by the GluN2D-selective antagonists UBP141 (3 μm) and PPDA (0.5 μm). D–F, plots illustrating averaged EPSC amplitude during application of ifenprodil, UBP141 and PPDA (n = 8 for ifenprodil, 11 for UBP141 and 6 for PPDA). G, bar graph showing averaged EPSC amplitude in the presence of antagonists; all 3 compounds depressed EPSCs to a similar extent.

Induction of LTD in interneurons

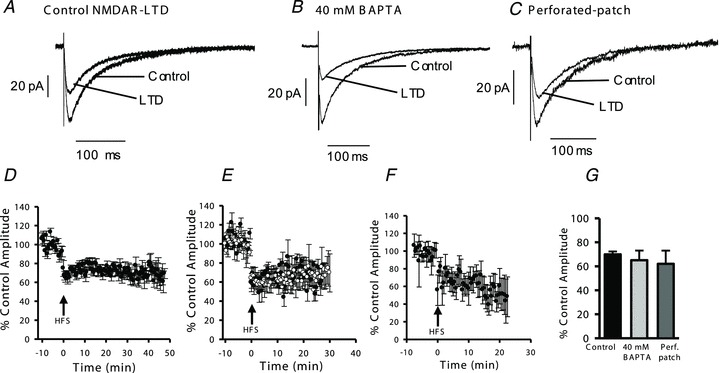

In granule cells, LTP or LTD of NMDARs can be induced by HFS, with the direction of plasticity depending on intracellular Ca2+ buffering (Harney et al. 2006). In interneurons, under conditions of low calcium buffering (0.2 mm EGTA intracellular solution) HFS induced LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs (EPSC amplitude 70 ± 2% of control, n = 21; Fig. 4A, D and G). There was no significant change in PPR following LTD induction (control PPR 1.4 ± 0.3, LTD PPR 1.3 ± 0.2, n = 9, P = 0.18). NMDAR-LTD was insensitive to strong calcium buffering with intracellular BAPTA (40 mm; Fig. 4B, E and G) as LTD induced in the presence of BAPTA was comparable to interleaved controls in slices from the same animals (68 ± 5% of control in experiments with standard Ca2+ buffering and 65 ± 8% of control with BAPTA intracellular, n = 6 controls and 8 BAPTA, P = 0.4; Fig. 4E and G). We also tested a theta burst stimulation protocol (3 bursts of 5 stimuli at 100 Hz, interburst interval 200 ms) and recorded similar LTD to that observed with our HFS protocol (NMDAR-EPSC amplitude 70 ± 5% of control, n = 6; data not shown).

Figure 4. HFS induces LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons and this form of LTD is insensitive to strong intracellular Ca2+ buffering.

A, traces of averaged EPSCs in control conditions (recorded with standard intracellular solution containing 0.2 mm EGTA) and following induction of LTD by HFS stimulation. B, traces showing EPSCs recorded in control conditions (using intracellular solution containing 40 mm BAPTA) and following induction of LTD. C, traces showing EPSCs recorded using the perforated-patch configuration during baseline recording and after HFS. D, HFS-induced LTD of NMDAR EPSCs recorded using standard intracellular solution containing 0.2 mm EGTA (n = 21). E, plots illustrating LTD induced by HFS in interneurons recorded using intracellular solution containing 40 mm BAPTA (open symbols, n = 8) and interleaved controls recorded using standard intracellular solution (filled symbols, n = 6). F, in recordings made using the perforated patch configuration HFS induced LTD that was similar to LTD observed in whole-cell recordings. G, bar graph illustrating averaged EPSC amplitudes following induction of LTD. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of LTD recorded with 40 mm BAPTA intracellular (ANOVA, P = 0.49) or in perforated patch recordings (ANOVA, P = 0.5) compared to controls recorded with standard intracellular solution (n = 21 controls, 8 BAPTA and 5 perforated patch).

Studies of LTP of AMPAR-mediated synaptic currents in interneurons have suggested that the whole-cell patch clamp configuration precludes the induction of LTP in interneurons, due to washout of essential intracellular factors (Lamsa et al. 2005). We therefore tested if plasticity of NMDAR-EPSCs was altered in nystatin-perforated patch clamp recordings. NMDAR-EPSCs recorded in the perforated patch configuration had similar amplitude and decay kinetics compared to whole-cell recordings (amplitude 29 ± 12 pA, τw 56 ± 9 ms, n = 5). In response to HFS, LTD was induced (62 ± 11% of control, n = 5; Fig. 4C, F and G) that was indistinguishable from LTD observed in whole-cell recordings (ANOVA, P = 0.5). Access resistance did not change significantly over the duration of these experiments, with pre-HFS values of 66 ± 6 MΩ and 74 ± 9 MΩ post-HFS (n = 5, P = 0.07).

LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs involves removal of GluN2D-containing receptors from the synapse and actin depolymerisation

We have previously demonstrated that LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells was associated with an increased synaptic current mediated by GluN2D-containing NMDARs, which were normally located extrasynaptically (Harney et al. 2008). The sensitivity of interneuron NMDAR-EPSCs to PPDA and UBP141, indicating the presence of GluN2D-containing receptors at the synapse led us to investigate whether LTD may involve a converse movement of such receptors out of the synapse. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effect of PPDA applied following HFS and establishment of LTD. PPDA (0.5 μm) had no effect on NMDAR-EPSCs following induction of LTD (LTD 72 ± 6% of control at 10 min post-HFS and 68 ± 10% of control at 35–40 min post-HFS in the presence of PPDA, n = 5, ANOVA, P = 0.1; Fig. 5A, C and E). In interleaved controls using HFS-naive slices prepared from the same animals, PPDA reversibly depressed NMDAR-EPSCs to 58 ± 5% of control amplitude (Fig. 5B, D and E) in a similar manner to that described previously (Fig. 3). Thus, LTD was associated with reduced activation of GluN2D-containing receptors by synaptically released glutamate.

Figure 5. LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs is associated with a loss of inhibition by the GluN2D-selective antagonist PPDA.

A, averaged EPSCs recorded in control conditions, following induction of LTD and with subsequent application of PPDA (0.5 μm), which had no effect when applied after LTD induction. B, averaged EPSCs from interleaved controls showing inhibition of EPSCs by 0.5 μm PPDA. C, graph illustrating HFS-induced LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs. PPDA had no effect on EPSC amplitude when applied 10 min following induction of LTD. D, graph showing NMDAR-EPSC amplitude in experiments interleaved with those in C. PPDA application reversibly depressed NMDAR-EPSCs by 40% in slices which had not undergone HFS. E, bar graph showing averaged EPSC amplitudes following LTD induction, following LTD induction and subsequent perfusion of PPDA and in PPDA without prior induction of LTD (n = 5 for LTD + PPDA and 6 for PPDA alone).

To test if the HFS-induced removal of GluN2D-containing NMDARs involved reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton, we used jasplakinolide (Jpk), which inhibits actin depolymerisation. Intracellular perfusion with Jpk (2 μm) prevented induction of NMDAR-LTD by HFS (102 ± 19% of control, n = 5; Fig. 6A, D and G) while NMDAR-LTD (65 ± 3% of control, n = 6; Fig. 6B, E and G) was observed in interleaved experiments where the vehicle, DMSO (0.2%), was included in the intracellular solution. Intracellular perfusion of cells with Jpk (in the absence of HFS) had no significant effect on NMDAR-EPSC amplitude, inducing slight rundown after whole-cell recording for up to 1 h with NMDAR-EPSC amplitude measuring 93 ± 7% of control at 50–60 min (compared to 0–10 min, n = 6; Fig. 6C, F and G). These results demonstrate that while stabilising actin does not significantly affect synaptic NMDARs during baseline stimulation, depolymerisation of actin is necessary for HFS-induced LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs.

Figure 6. Actin-depolymerisation is essential for LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs.

A, averaged control EPSCs and following HFS, recorded with 2 μm jasplakinolide (Jpk) in the intracellular solution. B, averaged EPSCs from interleaved controls with the vehicle, 0.2% DMSO in the intracellular solution during baseline recordings and following HFS. C, averaged EPSCs recorded with jasplakinolide in the intracellular solution. Traces show EPSCs recorded during the first 10 min and after 50–60 min of recording. D, intracellular jasplakinolide prevented induction of LTD by HFS. Plot shows no change in averaged EPSC amplitude following HFS. E, control experiments, interleaved with those shown in D where 0.2% DMSO was added to the intracellular solution, displaying normal LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs. F, plot showing NMDAR-EPSC amplitude during recordings with jasplakinolide in the intracellular solution, which did not significantly alter NMDAR-EPSCs after whole-cell recording for up to 60 min. G, bar graph illustrating averaged EPSC amplitudes following HFS with intracellular solution containing jasplakinolide or 0.2% DMSO and following 1 h recording with intracellular jasplakinolide alone; *P < 0.05 vs. control, n = 5 for HFS/Jpk, 6 for HFS/DMSO and 6 for Jpk/60 min.

Ca2+-dependent potentiation of NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons

HFS induced LTD in interneurons in conditions of standard Ca2+ buffering (0.2 mm EGTA, as described above) while NMDAR-LTP can be readily induced in granule cells (Harney et al. 2006). Interneurons have different calcium buffering capacities compared to principal cells (Lee et al. 2000), in addition to morphological differences such as a lower density of dendritic spines characteristic of some subtypes (Freund & Buzsáki, 1996); therefore we hypothesized that the HFS-induced increase in intracellular calcium was not sufficient to induce NMDAR-LTP in interneurons. To maximise Ca2+ influx during HFS we briefly increased the extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 2 mm to 10 mm prior to HFS and this high Ca2+/HFS protocol induced a large, sustained potentiation which appeared to be LTP as it was not reversed upon switching back to the control 2 mm Ca2+ ACSF. In these experiments baseline NMDAR-EPSCs were recorded under normal conditions of 2 mm Ca2+, and slices were then perfused with ACSF containing 10 mm Ca2+ for 5 min to allow equilibration prior to HFS. Immediately after HFS, perfusion was resumed with 2 mm Ca2+ ACSF and EPSCs recorded. This protocol resulted in a potentiation of NMDAR-EPSCs to 234 ± 36% of control (Fig. 7A, C and F, n = 9). As standard HFS alone did not induce potentiation it was not possible to perform occlusion experiments to verify if this Ca2+-dependent potentiation is the same as the NMDAR-LTP we previously reported in granule cells. In similar experiments in which the intracellular solution contained 40 mm BAPTA, the high Ca2+/HFS protocol failed to induce potentiation and instead resulted in LTD (78 ± 5% of control, n = 5; Fig. 7B, D and F). One approach to overcome strong endogenous calcium buffering capacity is to reduce calcium extrusion, as reported in a study of CA2 pyramidal cells by Simons et al. (2009). Intracellular perfusion of interneurons with the Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor carboxyeosin (10 μm) had no effect on the properties of NMDAR-EPSCs which were similar to controls (amplitude 51 ± 15 pA, rise time 11 ± 4 ms, τw 77 ± 10 ms, n = 5) and HFS resulted in LTD which was also similar to that recorded with normal intracellular solution (66 ± 6% of control, n = 5, Fig. 7E and F). These findings suggest that calcium extrusion is unlikely to account for the lack of NMDAR-LTP in these cells.

Figure 7. LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs can be induced in interneurons by HFS delivered in the presence of elevated extracellular Ca2+ (10 mm) and this form of LTP is abolished by strong postsynaptic Ca2+ buffering.

A, averaged EPSCs recorded in control conditions and following HFS in the presence of transiently elevated extracellular Ca2+. Control and post-HFS EPSCs were recorded in normal ACSF containing 2 mm Ca2+. B, traces show averaged EPSCs recorded in control conditions using intracellular solution containing 40 mm BAPTA and following HFS delivered in the presence of elevated extracellular Ca2+. C, LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs was induced when HFS was delivered during a transient (5 min) elevation of extracellular Ca2+ from 2 mm to 10 mm. Following return to normal ACSF containing 2 mm Ca2+, EPSCs remained strongly potentiated for the duration of recordings. D, strong intracellular Ca2+ buffering with 40 mm BAPTA in the postsynaptic cell prevented the induction of LTP by the HFS/high Ca2+ protocol, resulting in a transient enhancement of EPSC amplitude followed by depression. E, plot showing LTD induced by HFS, in normal, 2 mm Ca2+-containing ACSF, in interneurons recorded with 10 μm carboxyeosin (CBE) in the intracellular solution. F, bar graph showing averaged NMDAR-EPSC amplitudes following the HFS/high Ca2+ LTP induction protocol using normal intracellular solution and intracellular containing 40 mm BAPTA and following the standard HFS protocol in cells recorded with 10 μm carboxyeosin intracellular (n = 9 for control high Ca2+/HFS, 8 for cells recorded with BAPTA and 5 for cells recorded with carboxyeosin).

Postsynaptic activation of PKC potentiates NMDAR-EPSCs

PKC has previously been associated with a role in the trafficking of NMDARs with PKC activation leading to increased surface expression of NMDARs (Lan et al. 2001; Lin et al. 2006) and LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in dentate granule cells is PKC-dependent (O’Connor et al. 1994, 1995a; Obokata et al. 1997; Harney, unpublished observations). Direct activation of PKC by bath application of the phorbol ester phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 100 nm, perfused for 20 min) resulted in a sustained potentiation of NMDAR-EPSCs following washout of PMA (170 ± 27% of control, n = 6; Fig. 8A, C and D). When the PKC inhibitory peptide fragment PKC19−36 (10 μm) was added to the intracellular pipette solution, PMA application induced only a transient potentiation of NMDAR-EPSCs (123 ± 3% of control; Fig. 8C open symbols) with EPSC amplitude returning to baseline values following washout of PMA (96 ± 14% of control, P = 0.34, n = 6; Fig. 8B, C and D). These experiments demonstrate that while phorbol ester can transiently potentiate NMDAR-EPSCs, probably via a presynaptic mechanism, postsynaptic activation of PKC is required to induce sustained potentiation.

Figure 8. Direct activation of PKC induces LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs.

A, averaged traces showing NMDAR-EPSCS in control conditions and following a 20 min incubation with the phorbol ester, PMA (100 nM). B, averaged traces showing NMDAR-EPSCS in control conditions, recorded with the PKC inhibitory peptide PKC19−36 (10 μm) in the intracellular solution which abolished potentiation induced by PMA. C, plots illustrate potentiation of NMDAR-EPSC amplitude induced by PMA in recordings using standard intracellular solution (filled symbols, n = 6) and this potentiation was abolished in recordings with PKC19−36 in the intracellular solution (open symbols, n = 6). D, bar graph summarises NMDAR-EPSC amplitudes following washout of PMA for both controls and recordings with PKC19−36 in the intracellular solution.

Inhibition of group II mGluRs unmasks LTP in a subset of interneurons

We tested if the group II mGluR antagonist DCG-IV inhibited synaptic transmission in interneurons as it does at medial perforant path synapses on granule cells. Perfusion of DCG-IV (1 μm) depressed NMDAR-EPSCs in all interneurons tested (amplitude 71 ± 11% of control, n = 7). When HFS was given in the presence of a low concentration of LY341495 (1 μm), to inhibit group II mGluRs, LTP was induced in half of the interneurons tested (127 ± 7% of control, n = 4 of 8 cells; Fig. 9A, E and F). In the remaining cells, HFS induced LTD similar to that observed in the absence of LY341495 (72 ± 5% of control, n = 4; Fig. 9B, E and F). There were no significant differences in the pre-HFS control NMDAR-EPSC properties between the 2 groups of cells. Using a higher concentration of LY341495 (100 μm), which inhibits both group I and group II mGluRs (Kingston et al. 1998), HFS resulted in LTP in four cells (154 ± 17% of control, n = 4, Fig. 9C, G and H) and LTD in six cells (61 ± 7% of control, n = 6; Fig. 9D, G and H). Since the observed results were similar for both high and low concentrations of LY341495 we conclude that inhibiting group II mGluRs allowed the induction of LTP in a subset of interneurons.

Figure 9. Inhibition of group II mGluRs unmasks LTP in a subset of interneurons.

A, averaged EPSCs recorded in 1 μm LY341495 displaying potentiation following HFS. B, averaged EPSCs recorded in 1 μm LY341495 from interneurons displaying LTD following HFS. C, averaged EPSCs recorded in 100 μm LY341495 displaying potentiation following HFS. D, averaged EPSCs recorded in 100 μm LY341495 from interneurons displaying LTD following HFS. E, plot summarising changes in mean NMDAR EPSC amplitude after HFS for all cells recorded in 1 μm LY341495, EPSCs in 4 interneurons were potentiated (green symbols) while depression was observed in the remaining 4 cells (black symbols). F, bar graph summarising the changes in NMDAR-EPSC amplitude following depression or potentiation induced by HFS in the presence of 1 μm LY341495. G, plot summarising changes in mean NMDAR-EPSC amplitude after HFS for cells recorded in 100 μm LY341495, EPSCs were potentiated in 4 cells (green symbols) and depressed in 6 cells (black symbols). H, bar graph summarising the changes in NMDAR-EPSC amplitude following potentiation or depression induced by HFS in the presence of 100 μm LY341495.

Discussion

In this study we have identified differences in NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents and plasticity of NMDAR-EPSCs in dendrite-targeting interneurons in dentate gyrus compared to the principal granule cells. Our findings show kinetic and pharmacological differences in NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission at medial perforant path synapses on interneurons compared to the synapses made by the same axons on granule cells. NMDAR-EPSCs had significantly slower decay kinetics in interneurons compared to granule cells in dentate gyrus (Fig. 1) and were depressed by the antagonists PPDA and UBP141, indicating expression of GluN2D-containing receptors at the synapse (Fig. 3). There is evidence for strong expression of GluN2D mRNA in interneurons in the hippocampus, including the hilar region of dentate gyrus (Standaert et al. 1996), although this receptor subtype is usually expressed at extrasynaptic locations in principal cells (Momiyama et al. 1996; Misra et al. 2000; Momiyama, 2000; Brickley et al. 2003). In our data, NMDAR-EPSC τw was correlated with amplitude for interneurons but not for granule cells; however, there was no significant correlation between τw and rise time for interneurons. If the slower decay kinetics in interneurons were the result of electrotonic filtering, then this would be expected to affect the faster rise time more than EPSC decay time course (Spruston et al. 1993). Furthermore, since the slow kinetics of NMDAR-mediated conductances are not appreciably distorted by dendritic filtering, compared to the faster rise times (Hausser & Roth, 1997), this is unlikely to completely account for the twofold difference in decay kinetics compared to granule cells. Differences in NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons compared to principal cells have been previously reported such as the two populations of stratum radiatum interneurons in CA1 which were distinguished on the basis of having fast and slow EPSP kinetics, with the prolonged EPSPs having a larger NMDAR-mediated component (Maccaferri & Dingledine, 2002). Another study in stratum radiatum interneurons described NMDAR-EPSCs that had similar kinetics to those in pyramidal cells (Sah et al. 1990) while NMDAR-EPSCs in oriens/alveus interneurons had faster decay kinetics compared to pyramidal cells (Perouansky & Yaari, 1993). There are also synapse-specific differences in NMDAR subunit expression in CA3 interneurons with some synapses expressing relatively fast EPSCs with a small GluN2B-mediated component and calcium-permeable AMPARs (Lei & McBain, 2002). Slow EPSPs in interneurons were shown to permit greater integration of signals from separate synaptic inputs, resulting in variably timed spike outputs (Maccaferri & Dingledine, 2002) which would mediate prolonged but imprecise inhibition of principal cell dendrites. This contrasts with parvalbumin-expressing, somatically synapsing basket cells, which have fast EPSCs (Geiger et al. 1997) and are specialised to coordinate precisely timed spiking activity in principal cells (Pouille & Scanziani, 2001; Bartos et al. 2002).

We have demonstrated synaptic plasticity of NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons with very different properties to those in granule cells. Using the same HFS protocol and recording conditions where we have previously observed bidirectional plasticity in granule cells, we record only LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons. HFS-induced LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in granule cells depends on intracellular calcium buffering, with LTD being induced with a high intracellular concentration of the Ca2+ buffer EGTA (10 mm) and LTP induced with a lower EGTA concentration (0.2 mm) (Harney et al. 2006). In interneurons, this stimulation protocol resulted in LTD even in conditions of relatively low calcium buffering (0.2 mm EGTA), and interneuron LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs was resistant to strong exogenous calcium buffering using 40 mm intracellular BAPTA. This Ca2+-independent depression might suggest a presynaptic form of plasticity; however this is not definitive as a postsynaptic LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs has been described in CA1 pyramidal cells which was also insensitive to a high concentration of intracellular BAPTA (Ireland & Abraham, 2009). In an additional similarity to the LTD described by Ireland and Abraham, NMDAR-LTD was inhibited by intracellular application of the actin stabilising agent, jasplakinolide (Fig. 6), confirming that postsynaptic actin reorganisation is required for this plasticity. Short term synaptic plasticity also had distinct properties at interneuron synapses, which displayed paired-pulse facilitation in place of the paired-pulse depression recorded at medial perforant path inputs to granule cells (Fig. 2), indicating differences in transmitter release probability. This is additional evidence of target cell-specific properties of synaptic transmission mediated by the same axons (Pelkey & McBain, 2008; Croce et al. 2010).

In granule cells, NMDAR-LTP was associated with lateral movement of GluN2D-containing receptors, with a switch from PPDA-insensitive NMDAR-EPSCs to PPDA-sensitive synaptic currents following induction of LTP (Harney et al. 2008). Therefore, we examined the possibility that LTD in interneurons may involve removal of receptors containing GluN2D subunits. Interestingly, LTD of NMDAR-EPSCs in interneurons was accompanied by a loss of sensitivity to PPDA (Fig. 4), suggesting that GluN2D-containing receptors are removed from the synapse during LTD. Removal of synaptic NMDARs may require reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton and this hypothesis is supported by the finding that inhibiting actin depolymerisation with jasplakinolide prevented NMDAR-LTD (Fig. 6). This is in agreement with several previous studies, in principal cells, demonstrating NMDAR-LTD which required actin depolymerisation (Morishita et al. 2005; Ireland & Abraham, 2009; Peng et al. 2009) but was independent of dynamin-dependent endocytosis (Morishita et al. 2005), suggesting that synaptic depression was mediated by lateral movement of NMDARs out of the synapse to the extrasynaptic membrane.

Previous studies of NMDAR plasticity have identified a role for mGluRs, in particular group I mGluRs (O’Connor et al. 1994; Harney et al. 2006; Rebola et al. 2008; Ireland & Abraham, 2009; Rebola et al. 2011). We first tested if medial perforant path synapses on dendrite-targeting interneurons were modulated by group II mGluRs as these receptors are densely expressed on axon terminals at medial perforant path inputs to granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (Shigemoto et al. 1997) and synaptic transmission at perforant path-granule cell synapses is depressed by group II mGluR agonists (Brown & Reymann, 1995; Macek et al. 1996; Kilbride et al. 1998). We found that DCG-IV inhibited perforant path-evoked EPSCs in interneurons by 30%, similar to reported effects of DCG-IV at perforant path inputs to dentate gyrus basket cells (Sambandan et al. 2010). However, from our results, the role of mGluRs in NMDAR plasticity in interneurons was not clear; inhibiting group II mGluRs with a low concentration of LY341495 (1 μm) or blocking both group I and II mGluRs with a higher concentration of LY341495 (100 μm) revealed LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in only a subset of interneurons tested (Fig. 9). Since similar results were obtained with both concentrations of LY341495 it is likely that inhibition of group II mGluRs was permissive for LTP in some cells and that, as this was not seen in all cells, this effect may depend on prior synaptic history and mGluR activity, for example HFS and previous mGluR activation inhibits mGluR-dependent LTD in dentate granule cells (Rush et al. 2002). In CA3 stratum lucidum interneurons, HFS-induced LTP was observed only after priming with a group III mGluR agonist, l-AP4, which resulted in internalization of presynaptic mGluR7 receptors and blocked the induction of LTD (Pelkey et al. 2005, 2008). Alternatively, these results may reflect the properties of more than one population of interneurons. While our standard HFS protocol failed to induce potentiation in any interneurons tested, a sustained potentiation, or apparent LTP, of NMDAR-EPSCs was induced using a modified protocol that involved elevating extracellular Ca2+ during HFS (Fig. 7) or by direct activation of PKC by the phorbol ester, PMA (Fig. 8). HFS-induced LTP of AMPAR-EPSCs has been reported in CA3 stratum lacunosum-moleculare interneurons and in some CA1 interneurons in stratum radiatum, stratum oriens-alveus and lacunosum-moleculare (Ouardouz & Lacaille, 1995) and in basket cells in dentate gyrus. However, certain interneuron subtypes are resistant to LTP induction using standard protocols, such as the parvalbumin-positive bistratified cells and CB1-positive basket cells in CA1 (Nissen et al. 2010) and a subset of stratum radiatum (Lamsa et al. 2005; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996) and stratum lacunosum moleculare interneurons (Perez et al. 2001). Our results may present an underlying basis for this resistance to LTP. If strong synaptic stimulation favours depression of NMDAR-mediated transmission in interneurons, then this form of metaplasticity would impede induction of AMPAR-LTP. Another possible reason for the difficulty of inducing LTP in physiological calcium concentrations is that many interneurons have a high calcium buffering capacity due to the expression of calcium binding proteins (Lee et al. 2000; Aponte et al. 2008). However this may not apply to all interneuron subtypes; for instance dendritic O-LM interneurons in CA1 have a relatively low calcium buffering capacity (Liao & Lien, 2009). Further investigation is required to determine if an increase in intracellular calcium sufficient to induce NMDAR-LTP can be attained using more physiological stimuli compared to the protocol we used here.

The finding that directly activating PKC with the phorbol ester PMA enhances NMDAR-EPSCs is in agreement with the previously described role for PKC in mediating LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs in principal cells in dentate gyrus (O’Connor et al. 1994, 1995b; Harney, unpublished observations) and at the mossy fibre input to CA3 pyramidal cells (Kwon & Castillo, 2008). PMA had no sustained effect on NMDAR-EPSC amplitude when PKC was inhibited by intracellular PKC19−36, confirming that this was a postsynaptic effect. PKC activation has been shown to regulate the expression and trafficking of NMDARs with surface membrane expression of heterologously expressed NMDARs being increased by phorbol ester activation of PKC (Lin et al. 2006; Lau et al. 2010) and NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents being potentiated by activation of PKC (Obokata et al. 1997). In addition, surface membrane mobility of NMDARs in principal cells is increased by phorbol ester activation of PKC (Groc et al. 2004). Our findings show that PKC also has a role in regulating NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission in interneurons.

Plasticity in specific interneuron populations should act to differentially regulate disynaptic inhibition on to distinct somato-dendritic compartments and the interneurons studied here synapse on the dendrites of granule cells. Therefore, we predict that the predominant LTD of excitatory inputs to these interneurons, resulting in reduced inhibition, should facilitate the induction of LTP at perforant path inputs to granule cells. Indeed, strong local inhibition of granule cells necessitates the use of GABAA receptor antagonists in in vitro LTP studies in dentate gyrus (Wigstrom & Gustafsson, 1983). Reduced inhibition may also have pathological consequences in conditions such as epilepsy, and enhanced presynaptic depression of excitatory inputs to hilar interneurons has been described in an animal model of epilepsy (Doherty & Dingledine, 2001). However, it should also be noted that excitatory input to surviving hilar interneurons is increased in late stages of epilepsy in an animal model (Halabisky et al. 2010).

Our results demonstrate that opposite forms of plasticity of NMDARs (LTD vs. LTP) occur at medial perforant path inputs to interneurons compared to that previously described in granule cells. Such target-specific plasticity is similar to that described in stratum lucidum interneurons in CA3 (Pelkey & McBain, 2008). An overriding depression of excitatory drive on to interneurons in response to strong perforant path activation may have long-lasting effects on dentate gyrus processing, and, in agreement, a computational study concluded that depression of hilar interneuron activity would positively modulate the pattern separation function of the dentate gyrus (Myers CE, 2009). Much research has been done to elucidate the synaptic properties and functional specialization of specific interneuron populations (Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008); understanding the dynamic and plastic properties of inhibitory circuits is integral to advancing our understanding of hippocampal function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland.

Glossary

- AMPAR

AMPA receptor

- HFS

high frequency stimulation

- Jpk

jasplakinolide

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- NMDAR

NMDA receptor

- NMDAR-LTD

long-term depression of NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents

- NMDAR-LTP

long-term potentiation of NMDAR-mediated synaptic currents

- PPR

paired-pulse ratio

Author contributions

All experiments were performed in the Department of Physiology, Trinity College Dublin. S.H. and R.A. conceived and designed experiments. S.H. performed experiments and analysed the data. Both authors participated in writing the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Aponte Y, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Efficient Ca2+ buffering in fast-spiking basket cells of rat hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 2008;586:2061–2075. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrar S, Zhou Z, Ren W, Jia Z. Ca(2+) permeable AMPA receptor induced long-term potentiation requires PI3/MAP kinases but not Ca/CaM-dependent kinase II. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Frotscher M, Meyer A, Monyer H, Geiger JR, Jonas P. Fast synaptic inhibition promotes synchronized gamma oscillations in hippocampal interneuron networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13222–13227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192233099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir ZI, Alford S, Davies SN, Randall AD, Collingridge GL. Long-term potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Nature. 1991;349:156–158. doi: 10.1038/349156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta N, Berton F, Bianchi R, Brunelli M, Capogna M, Francesconi W. Long-term potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs in guinea-pig hippocampal slices. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:850–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley SG, Misra C, Mok MHS, Mishina M, Cull-Candy SG. NR2B and NR2D subunits coassemble in cerebellar colgi cells to form a distinct NMDA receptor subtype restricted to extrasynaptic sites. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4958–4966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04958.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Reymann KG. Metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists reduce paired-pulse depression in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1995;196:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11825-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Schwartzkroin PA. Interneurons and inhibition in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vivo. J Neurosci. 1995;15:774–789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00774.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce A, Pelletier JG, Tartas M, Lacaille J-C. Afferent-specific properties of interneuron synapses underlie selective long-term regulation of feedback inhibitory circuits in CA1 hippocampus. The Journal of Physiology. 2010;588:2091–2107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MO, Hunt J, Middleton S, LeBeau FE, Gillies MJ, Davies CH, Maycox PR, Whittington MA, Racca C. Region-specific reduction in entorhinal gamma oscillations and parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in animal models of psychiatric illness. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2767–2776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5054-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty J, Dingledine R. Reduced Excitatory Drive onto Interneurons in the Dentate Gyrus after Status Epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2048–2057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02048.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in the Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan EJ, Calixto E, Barrionuevo G. Bidirectional Hebbian plasticity at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses on CA3 interneurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14042–14055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4848-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan EJ, Cosgrove KE, Barrionuevo G. Multiple forms of long-term synaptic plasticity at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses on interneurons. Neuropharmacology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JR, Lubke J, Roth A, Frotscher M, Jonas P. Submillisecond AMPA receptor-mediated signalling at a principal neuron-interneuron synapse. Neuron. 1997;18:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc L, Heine M, Cognet L, Brickley K, Stephenson FA, Lounis B, Choquet D. Differential activity-dependent regulation of the lateral mobilities of AMPA and NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:695–696. doi: 10.1038/nn1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabisky B, Parada I, Buckmaster PS, Prince DA. Excitatory Input Onto Hilar Somatostatin Interneurons Is Increased in a Chronic Model of Epilepsy. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;104:2214–2223. doi: 10.1152/jn.00147.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZS, Buhl EH, Lorinczi Z, Somogyi P. A high degree of spatial selectivity in the axonal and dendritic domains of physiologically identified local-circuit neurons in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:395–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnett MT, Bernier BE, Ahn KC, Morikawa H. Burst-timing-dependent plasticity of NMDA receptor-mediated transmission in midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2009;62:826–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney SC, Jane DE, Anwyl R. Extrasynaptic NR2D-Containing NMDARs Are Recruited to the Synapse during LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11685–11694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3035-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney SC, Rowan M, Anwyl R. Long-term depression of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission is dependent on activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and is altered to long-term potentiation by low intracellular calcium buffering. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1128–1132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2753-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser M, Roth A. Estimating the time course of the excitatory synaptic conductance in neocortical pyramidal cells using a novel voltage jump method. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7606–7625. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07606.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland DR, Abraham WC. Mechanisms of group I mGluR-dependent long-term depression of NMDA receptor-mediated transmission at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1375–1385. doi: 10.1152/jn.90643.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbride J, Huang LQ, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Presynaptic inhibitory action of the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists, LY354740 and DCG-IV. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;356:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston AE, Ornstein PL, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Mayne NG, Burnett JP, Belagaje R, Wu S, Schoepp DD. LY341495 is a nanomolar potent and selective antagonist of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal Diversity and Temporal Dynamics: The Unity of Hippocampal Circuit Operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova T, Fuchs EC, Ponomarenko A, von Engelhardt J, Monyer H. NMDA Receptor Ablation on Parvalbumin-Positive Interneurons Impairs Hippocampal Synchrony, Spatial Representations, and Working Memory. Neuron. 2010;68:557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H-B, Castillo PE. Long-Term Potentiation Selectively Expressed by NMDA Receptors at Hippocampal Mossy Fiber Synapses. Neuron. 2008;57:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laezza F, Dingledine R. Voltage-Controlled Plasticity at GluR2-Deficient Synapses Onto Hippocampal Interneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:3575–3581. doi: 10.1152/jn.00425.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laezza F, Dingledine R. Induction and expression rules of synaptic plasticity in hippocampal interneurons. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K, Heeroma JH, Kullmann DM. Hebbian LTP in feed-forward inhibitory interneurons and the temporal fidelity of input discrimination. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:916–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa KP, Heeroma JH, Somogyi P, Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. Anti-Hebbian Long-Term Potentiation in the Hippocampal Feedback Inhibitory Circuit. Science. 2007;315:1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1137450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J-Y, Skeberdis VA, Jover T, Grooms SY, Lin Y, Araneda RC, Zheng X, Bennett MVL, Zukin RS. Protein kinase C modulates NMDA receptor trafficking and gating. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:382–390. doi: 10.1038/86028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Takayasu Y, Rodenas-Ruano A, Paternain AV, Lerma J, Bennett MVL, Zukin RS. SNAP-25 Is a Target of Protein Kinase C Phosphorylation Critical to NMDA Receptor Trafficking. J Neurosci. 2010;30:242–254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4933-08.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Rosenmund C, Schwaller B, Neher E. Differences in Ca2+ buffering properties between excitatory and inhibitory hippocampal neurons from the rat. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 2):405–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, McBain CJ. Distinct NMDA receptors provide differential modes of transmission at mossy fibre-interneuron synapses. Neuron. 2002;33:921–933. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CW, Lien CC. Estimating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and buffering in a dendritic inhibitory hippocampal interneuron. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1701–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Jover-Mengual T, Wong J, Bennett MVL, Zukin RS. PSD-95 and PKC converge in regulating NMDA receptor trafficking and gating. PNAS. 2006;103:19902–19907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609924104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Dingledine R. Control of Feedforward Dendritic Inhibition by NMDA Receptor-Dependent Spike Timing in Hippocampal Interneurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5462–5472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05462.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, McBain CJ. Long-term potentiation in distinct subtypes of hippocampal nonpyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5334–5343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05334.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek TA, Winder DG, Gereau RWT, Ladd CO, Conn PJ. Differential involvement of group II and group III mGluRs as autoreceptors at lateral and medial perforant path synapses. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3798–3806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty NK, Sah P. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors mediate long-term potentiation in interneurons in the amygdala. Nature. 1998;394:683–687. doi: 10.1038/29312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra C, Brickley SG, Wyllie DJA, Cull-Candy SG. Slow deactivation kinetics of NMDA receptors containing NR1 and NR2D subunits in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2000;525:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momiyama A. Distinct synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors identified in dorsal horn neurones of the adult rat spinal cord. J Physiol. 2000;523(Pt 3):621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momiyama A, Feldmeyer D, Cull-Candy SG. Identification of a native low-conductance NMDA channel with reduced sensitivity to Mg2+ in rat central neurones. J Physiol. 1996;494(Pt 2):479–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita W, Marie H, Malenka RC. Distinct triggering and expression mechanisms underlie LTD of AMPA and NMDA synaptic responses. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1043–1050. doi: 10.1038/nn1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CESH. A role for hilar cells in pattern separation in the dentate gyrus: A computational approach. Hippocampus. 2009;19:321–337. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen W, Szabo A, Somogyi J, Somogyi P, Lamsa KP. Cell Type-Specific Long-Term Plasticity at Glutamatergic Synapses onto Hippocampal Interneurons Expressing either Parvalbumin or CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1337–1347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JJ, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Long-lasting enhancement of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1994;367:557–559. doi: 10.1038/367557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JJ, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Tetanically induced LTP involves a similar increase in the AMPA and NMDA receptor components of the excitatory postsynaptic current: investigations of the involvement of mGlu receptors. J Neurosci. 1995a;15:2013–2020. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02013.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JJ, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor-mediated currents detected using the excised patch technique in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1995b;69:363–369. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00295-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obokata K, Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Differential effects of phorbol ester on AMPA and NMDA components of excitatory postsynaptic currents in dentate neurons of rat hippocampal slices. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouardouz M, Lacaille JC. Mechanisms of selective long-term potentiation of excitatory synapses in stratum oriens/alveus interneurons of rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:810–819. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Lavezzari G, Racca C, Roche KW, McBain CJ. mGluR7 Is a Metaplastic Switch Controlling Bidirectional Plasticity of Feedforward Inhibition. Neuron. 2005;46:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, McBain CJ. Target-cell-dependent plasticity within the mossy fibre-CA3 circuit reveals compartmentalized regulation of presynaptic function at divergent release sites. The Journal of Physiology. 2008;586:1495–1502. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Topolnik L, Yuan X-Q, Lacaille J-C, McBain CJ. State-Dependent cAMP Sensitivity of Presynaptic Function Underlies Metaplasticity in a Hippocampal Feedforward Inhibitory Circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:980–987. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Zhao J, Gu QH, Chen RQ, Xu Z, Yan JZ, Wang SH, Liu SY, Chen Z, Lu W. Distinct trafficking and expression mechanisms underlie LTP and LTD of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses. Hippocampus. 2009;20:646–658. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Yl, Morin F, Lacaille J-C. A hebbian form of long-term potentiation dependent on mGluR1a in hippocampal inhibitory interneurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:9401–9406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161493498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perouansky M, Yaari Y. Kinetic properties of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells versus interneurones. J Physiol. 1993;465:223–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F, Scanziani M. Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward inhibition. Science. 2001;293:1159–1163. doi: 10.1126/science.1060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebola N, Carta M, Lanore F, Blanchet C, Mulle C. NMDA receptor-dependent metaplasticity at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:691–693. doi: 10.1038/nn.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebola N, Lujan R, Cunha RA, Mulle C. Adenosine A2A Receptors Are Essential for Long-Term Potentiation of NMDA-EPSCs at Hippocampal Mossy Fiber Synapses. Neuron. 2008;57:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AM, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)-dependent long-term depression mediated via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is inhibited by previous high-frequency stimulation and activation of mGluRs and protein kinase C in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6121–6128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06121.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Hestrin S, Nicoll RA. Properties of excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded in vitro from rat hippocampal interneurones. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:605–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambandan S, Sauer J-F, Vida I, Bartos M. Associative Plasticity at Excitatory Synapses Facilitates Recruitment of Fast-Spiking Interneurons in the Dentate Gyrus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11826–11837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2012-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential Presynaptic Localization of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Subtypes in the Rat Hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sik A, Penttonen M, Buzsáki G. Interneurons in the Hippocampal Dentate Gyrus: an In Vivo intracellular Study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;9:573–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons SB, Escobedo Y, Yasuda R, Dudek SM. Regional differences in hippocampal calcium handling provide a cellular mechanism for limiting plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14080–14084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, Jaffe DB, Williams SH, Johnston D. Voltage- and space-clamp errors associated with the measurement of electrotonically remote synaptic events. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:781–802. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.2.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standaert DG, Bernhard Landwehrmeyer G, Kerner JA, Penney JB, Young AB. Expression of NMDAR2D glutamate receptor subunit mRNA in neurochemically identified interneurons in the rat neostriatum, neocortex and hippocampus. Molecular Brain Research. 1996;42:89–102. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Pais I, Bibbig A, LeBeau FEN, Buhl EH, Garner H, Monyer H, Whittington MA. Transient Depression of Excitatory Synapses on Interneurons Contributes to Epileptiform Bursts During Gamma Oscillations in the Mouse Hippocampal Slice. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;94:1225–1235. doi: 10.1152/jn.00069.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. LTP induction dependent on activation of Ni2+-sensitive voltage-gated calcium channels, but not NMDA receptors, in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1997a;78:2574–2581. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Ryanodine produces a low frequency stimulation-induced NMDA receptor-independent long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Physiol. 1996;495(Pt 3):755–767. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. Conditions for the induction of long-term potentiation and long-term depression by conjunctive pairing in the dentate gyrus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1997b;78:2569–2573. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt AJ, Sjostrom PJ, Hausser M, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. A proportional but slower NMDA potentiation follows AMPA potentiation in LTP. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigstrom H, Gustafsson B. Large long-lasting potentiation in the dentate gyrus in vitro during blockade of inhibition. Brain Research. 1983;275:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Rush A, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R. NMDA receptor- and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity induced by high frequency stimulation in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Physiol. 2001;533:745–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]