Abstract

The clinical presentation of spinal tumors is known to vary, in many instances causing a delay in diagnosis and treatment, especially with benign tumors. Neck or back pain and sciatica, with or without neurological deficits, are mostly caused by degenerative spine and disc disease. Spinal tumors are rare, and the possibility of concurrent signs of degenerative changes in the spine is high. We report a series of ten patients who were unsuccessfully treated for degenerative spine disease. They were subsequently referred for operative treatment to our department, where an initial diagnosis of a tumor was made. Two patients had already been operated on for disc herniations, but without long-lasting effects. In eight patients the diagnosis of a tumor was made preoperatively. In two cases the tumor was found intraoperatively. All patients showed radiological signs of coexisting degenerative spine disease, making diagnosis difficult. MRI was the most helpful tool for diagnosing the tumors. A frequent symptom was back pain in the recumbent position. Other typical settings that should raise suspicion are persistent pain after disc surgery and neurological signs inconsistent with the level of noted degenerative disease. Tumor extirpation was successful in treating the main complaints in all but one patient. There was an incidence of 0.5% of patients in which a spinal tumor was responsible for symptoms thought to be of degenerative origin. However, this corresponds to 28.6% of all spine-tumor patients in this series. MRI should be widely used to exclude a tumor above the level of degenerative pathology.

Keywords: Spinal tumor, Differential diagnosis of spinal disease, Symptoms of spine tumors

Introduction

In clinical practice it is always difficult to distinguish between common and rare lesions involving the spine on a clinical basis alone. Developments in neuroimaging have contributed to earlier and safer diagnoses concerning spine disease.[12,14] However, in times of low healthcare budgets one will not use every available diagnostic tool. Instead, decisions concerning the diagnostic armamentarium are based on the patient’s clinical appearance and the probable cause of his or her symptoms.

Thus, in the case of lumbago and sciatica, the most likely cause will be a disc herniation. The chosen diagnostic tool in most practices and hospitals will be an X-ray examination of the lumbar spine as well as a CT scan of the commonly involved disc levels. If these are negative, further investigation can lead to the correct diagnosis. However, if no additional imaging is done and treatment is conservative, without image-based diagnosis, this will in some cases delay a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We identified ten patients who were referred to our department within a 3.5-year period based on a diagnosis of degenerative spine disease. After admission they were diagnosed with spinal tumors. In this retrospective study we analyzed the signs and symptoms of these patients that could have lead to an earlier diagnosis or that could have promoted an intensified diagnostic procedure. A matched-pair analysis to compare the findings between patients with spine tumors and patients with degenerative spine disease was additionally performed to enhance the observations.

Methods

Between March 1997 and August 2000, our department treated 35 patients for a spinal tumor, 10 referred without correct diagnosis (28.6%). In the same period, 2,013 patients were referred for operative treatment of degenerative cervical or lumbar disc disease. This gave a total rate of 1.7% for spinal tumors in this surgical group. In 0.5% of patients a spinal tumor caused symptoms believed to be of degenerative nature.

We reviewed the charts and imaging studies of patients with spine tumors, paying attention to symptoms, intensity of image-based diagnostics and outcome after treatment. A comparison was made between the clinical findings in the patients with combined pathology and those with only spine tumors. Additionally, we performed a matched-pair analysis of the 35 spine tumor patients with 35 patients treated for degenerative spine disorders within the same period, matched for age, gender and time of treatment. For statistical analysis we used Fisher’s exact test and McNemar’s test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

There were five women and five men, with a mean age of 57.9 years. Mean duration of symptoms was 9.6 months ( range 0.5 to 18 months). The main patient complaints were back pain in eight cases, five of these reporting back pain in recumbent position. Eight cases had leg pain with strong correlation to a dermatome only in three cases. The lone case with cervical pathology had neck pain combined with gait disturbance. Acute sphincter disturbance was present only once. Severe neurological deficit could be detected in four cases.

In all ten patients there was radiological evidence of degenerative spine disease (Table 1). Every patient had received a spinal X-ray examination while still in out-patient care elsewhere. Also, every patient had been examined by CT scanning of the commonly involved spinal levels corresponding to his or her complaints. Two patients had already had operations (one for case 3 and two for case 10) for herniated lumbar discs. These had no effect for case 3’s main complaints and little and short lasting effect for case 10’s. Only two patients were additionally diagnosed with a lumbar MRI. In one case correct diagnosis was missed because the wrong level was examined. In another the pathology was misinterpreted and diagnosis was corrected intraoperatively.

Table 1.

Data for ten patients with spinal tumors identified in hospital after referral for treatment of degenerative spine disease

| Case, sex/age in years | Symptom duration | Main complaints | Out-of-hospital diagnostic imaging (diagnosis) | In-hospital imaging (diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, M/49 | 4 weeks | Recumbent back pain, sciatica along anterior thigh, both legs | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT and MRI (lumbar stenosis due to scoliosis) | Thoracolumbar MRI (astrocytoma T9–11) |

| 2, M/71 | 8 weeks | Recumbent back pain, neurogenic claudication | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (lumbar stenosis) | Myelography, CT bone scan, skeletal scintigram (metastatic tumor L2/3, lumbar stenosis L4/5) |

| 3, F/30 | 1.5 years | Recumbent back pain, acute sphincter disturbance | Lumbar disc herniation (failed back operation 1 year earlier) | Lumbar MRI (conus ependymoma) |

| 4, F/78 | 6 months | Recumbent back pain, leg pain both sides | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (lumbar stenosis) | Myelography, lumbar MRI (neurinoma L1/2) |

| 5, M/59 | 1 year | Back pain, leg pain left side | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (stenosis due to ankylosing spondylitis) | Thoracolumbar MRI (neurinoma L1/2) |

| 6, F/62 | 9 months | Sciatica left side | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (lumbar stenosis) | Thoracolumbar MRI (neurinoma L2/3) |

| 7, M/50 | 2 weeks | Back pain, sciatica right leg | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (calcified disc herniation L5/S1, recessus stenosis S1) | None (intraoperatively: intradural ganglioneuroma S1 root) |

| 8, F/68 | 1.5 years | Neck pain, progressive myelopathy | X-ray cervical spine, CT cervical spine (cervical stenosis C4/5/6) | Craniocervical MRI (meningioma C2) |

| 9, M/54 | 1 year | Back pain, sciatica left leg | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT and MRI (spondylarthrosis, lumbar juxtafacet cyst) | None (intraoperatively: neurinoma L5 root) |

| 10, F/73 | 1.5 years | Recumbent back pain, sciatica along anterior right thigh | Spinal X-ray, lumbar CT (disc herniation L3/4—already operated twice) | Thoracolumbar MRI (meningioma T2/3) |

Out-patient diagnoses that led to referral to our department after failure of conservative treatment included: lumbar stenosis in five cases, cervical stenosis in one case, disc herniation in two cases, failed back syndrome and juxtafacet cyst in one case. After admission, we performed additional imaging in eight patients, with six MRI scans and two myelographies as well as one skeletal scintigram and one CT bone scan. Reasons for this were discordant symptoms and previous imaging in four cases, while in four other cases the purpose was to clarify the extent of degenerative spinal pathology. In two patients no further imaging was performed. In all eight patients with additional imaging, the diagnosis of a spinal tumor was made preoperatively, whereas in the two cases without further imaging the diagnosis was made intraoperatively. The tumors were located above the degenerative pathology in all cases except the two with nerve root tumors. These were separated from the degenerative-diseased area by a mean distance of 3.65 segments (range 1–12 segments).

Table 2 summarizes the histological findings and locations for the tumors diagnosed in hospital for these ten patients. All patients but one were exclusively operated on for their tumors, not their additional degenerative pathology (see Table 3). Nine experienced benefit from their operation. One patient had a postoperative complication and consecutive deficits that resolved only partially. After a mean follow-up of 13 months, no patient in this series required further surgical treatment for the coexisting degenerative disease.

Table 2.

Summary of pathological findings and location of spine tumors in ten patients with coexistent degenerative spine disease

| Meningioma | Neurinoma | Ganglioneuroma | Ependymoma | Astrocytoma | Metastasis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | 1 | |||||

| Thoracic | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Thoracolumbar | 3 | |||||

| Conus | 1 | |||||

| Lumbar | 1 | |||||

| Nerve root | 1 | 1 |

Table 3.

Treatment and outcome in ten patients with spine tumors and coexisting degenerative spine disease

| Case | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Astrocytoma T9–11 | Incomplete resection | Less pain, ambulatory, no tumor progression | 2 years |

| 2 | Metastatic tumor L2/3, stenosis L4/5 | Decompression, radiation | Postoperative hematoma, re-operation, paresis L2 and L3, slow restitution | 1 year |

| 3 | Conus ependymoma | Complete excision | No pain, no deficits, no recurrence | 1.5 years |

| 4 | Neurinoma L1/2 | Complete excision | Slight back pain, no deficits, no tumor recurrence | 1 year |

| 5 | Neurinoma L1/2 | Complete excision | No pain, no deficits, no recurrence | 9 months |

| 6 | Neurinoma L2/3 | Complete excision | No pain, no deficits | 6 months |

| 7 | Ganglioneuroma S 1 root | Biopsy, decompression | Less pain, no deficit, no tumor progression | 1.5 years |

| 8 | Meningioma C2 | Complete excision | No new deficits, regredient myelopathy | 9 months |

| 9 | Neurinoma L5 root | Complete excision | No pain, no deficit | 1 year |

| 10 | Meningioma T2/3 | Complete excision | Slight back pain, no deficit | 6 months |

A group comparison between the ten patients with combined pathology, on the one hand, and the 25 with spine tumors only, on the other, revealed no significant differences for the clinical factors studied, except that patients with combined pathology complained significantly more often of back pain under loading, i.e., while standing or walking (p=0.0136, Fisher’s exact test, see Table 4). The matched-pair analysis between all spine tumor patients and the matched patients with degenerative disease exhibited significant differences regarding the incidence of unilateral leg pain (p=0.00023), as well as a positive Lasègue’s sign (p=0.00763, see Table 5). Both conditions were present significantly more often in the patients with degenerative spine disease. Although there was no significant difference in the frequency of back pain, either at rest or under loading, we observed that the combination of back pain at rest without back pain under loading only occurred in patients with spine tumors and never in the other group. This finding was, however, not of statistical significance.

Table 4.

Comparison of the ten patients with combined pathology vs all other patients suffering from spine tumors (Fisher’s exact test)

| Symptom/sign | P value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Back pain at rest | 0.3957 | n.s. |

| Back pain under loading | 0.0136 | Significant |

| Unilateral leg pain | 0.0898 | n.s. |

| Lasegue‘s sign | 0,147 | n.s. |

| Severe deficit | 0,7309 | n.s. |

Table 5.

Comparison of 35 spine tumor patients with 35 matched-pair patients with degenerative spine disease (McNemar’s sign test)

| Symptom/sign | P value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Back pain at rest | 0.8084 | No |

| Back pain under loading | 0.1336 | No |

| Unilateral leg pain | 0.00023 | Significant |

| Lasègue’s sign | 0.00763 | Significant |

| Severe deficit | 0.1484 | No |

Illustrative cases

Case 4

This 78-year-old woman experienced progressive back pain and pain radiating in both legs over 6 months. She was admitted for conservative treatment in a neurological department at another hospital. Despite adequate analgetic medication and physiotherapy, she worsened to the point that disabling pain kept her from walking or even standing. There were no neurological deficits. Pain was also present in the recumbent position and at night. A CT scan of L3 to S1( not shown) revealed degenerative changes with a maximum at level L3/4. These were interpreted as stenotic, resulting in a diagnosis of lumbar stenosis resistant to conservative management. The patient was referred to our hospital for operative intervention and a lumbar myelography was performed in order to determine the extent of stenosis. The post-myelographic CT scan at level L3/L4 showed only mild, lateral recessus stenosis on the right side, not explaining the bilateral complaints (Fig. 1, top). An MRI of the lumbar spine including the thoracolumbar region then disclosed an intradural tumor at L1/2 compressing the cauda equina (Fig. 1, bottom). After complete microsurgical excision of this neurinoma, the patient was pain-free except for slight, intermittent back pain for a follow-up period of one year.

Fig. 1.

Case 4. Top: post-myelographic CT scan at level L3/4, showing lateral recessus stenosis on the right side; bottom: MRI of the thoracolumbar region revealing an intradural tumor at L1/2 and confirming the lateral recessus stenosis at L3/4

Case 8

This 68-year-old woman suffered from intermittent neck pain, partially radiating into her arms. Over a period of 1.5 years, she developed progressive pain and noticed problems when doing her hobby, sewing. She also gradually began to have balance problems while walking. Clinically, there were signs of a cervical myelopathy with atactic gait, hyperreflexia and symmetrical sensory disturbances.

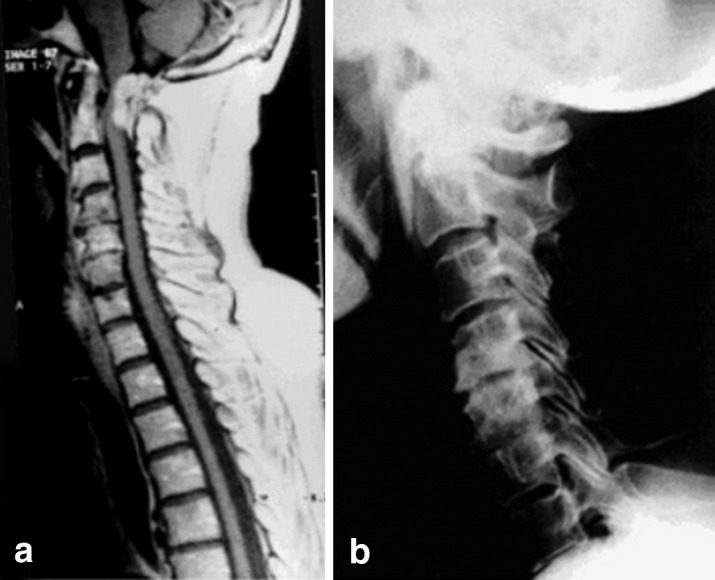

A CT scan of C3 to C8 ( not shown) and an X-ray examination of the spine (Fig. 2, left) done by the patient’s outpatient orthopedic consultant showed cervical spondylosis at the levels C4/5 and C5/6. Because of her progressive symptoms she was referred for surgery on her cervical stenosis, which was considered the cause of her myelopathic syndrome. We routinely use preoperative MRI scanning of the cervical spine in cases of myelopathy, to check for intramedullary changes. On this patient the MRI disclosed a dorsal extramedullary, intradural tumor at the craniocervical junction (Fig. 2, right). The presumed cervical stenosis was not of clinical significance. After an uncomplicated excision of the tumor, which proved to be a meningioma, the patient improved gradually with no new deficits.

Fig. 2.

Case 8. Left: X-ray of the cervical spine revealing spondylosis at C4/5 and C5/6; right: MRI disclosing a meningioma at the craniocervical junction

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of degenerative spine disease, especially concerning spinal tumors, has been the subject of numerous papers and textbooks [1,2,6,10,13,16]. Most authors state that the symptoms of tumors can mimic the typical clinical picture of disc herniation or lumbar stenosis. As symptoms may vary enormously, no definitive diagnosis can be made on the basis of clinical findings alone. In the literature there are frequent case reports of patients who have been diagnosed with a spinal tumor after long periods of treatment for degenerative spine lesions [4, 15]. Our aim was to determine whether, in a special subgroup of patients, i.e., patients with degenerative spine disease and coexistent spine tumors, diagnostic settings are present that should raise suspicion of a spinal tumor.

As confirmed by others, back pain exacerbated by the recumbent position was one major finding ( five of nine patients, 56%). Discogenic or radicular pain is exacerbated by the standing position or walking, and is atypically severe in a resting position. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, we were unfortunately unable to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in back pain behavior in the matched-pair analysis. Progressive back pain in a recumbent position was only noted in the group with combined pathology because of the special interest in these patients at the time of diagnosis. No systematic evaluation of this pain was performed in the other patients. Therefore there is a lack of data. Nevertheless, we noted a tendency for back pain under loading to be more likely to occur in patients with degenerative spine disease. The fact that the patients with combined pathology also had back pain under loading more often than all other spine tumor patients may somewhat explain why these patients have been misdiagnosed prior to admission in our institution.

Except in the two cases with nerve root tumors, only one of eight patients (12.5%) had pain distribution strictly projecting to a dermatome. This is atypical for a classical disc herniation syndrome or a classical syndrome of lumbar stenosis. This observation is enhanced by the highly significant differences that we found in our matched-pair analysis. Unilateral leg pain and a positive Lasègue’s sign are clear clinical signs of degenerative spine disease. This finding has also been stressed in recent studies[3, 11].

Persistent pain after an uncomplicated discectomy is not uncommon, and can surely indicate any form of failed-back-surgery syndrome. Still, if no clear diagnosis can be made or further treatment does not succeed, a spinal tumor cannot be ruled out. Any discordance between clinical presentation and radiological diagnosis should prompt the physician to perform further investigation. In our series, we initiated additional MRI in six cases and myelography in two. This led to definitive diagnosis in all eight cases, although in only half of these patients did we suspect a different reason for the symptoms.

One case with malignant osteoblastic spine disease is included in this series. This man suffered from previously undetected prostatic cancer, a condition known to be relatively slow to become symptomatic. In most cases of metastases to the spine, patients present with a fast progressing pain syndrome. Severe neurological deficits will often occur in the early course of disease. So this single case reflects the rarity with which malignant conditions of the spine are involved in the pitfalls discussed in this paper.

Literature on clinical series dealing with this issue is rare. Guyer et al. reported nine cases (1.2%) identified in a group of 744 patients presenting with symptoms similar to disc herniation and diagnosed with a spinal tumor by myelography in all cases [7]. Three of these patients complained of night pain. One patient was successfully treated for both a herniated disc and symptomatic tumor. Three patients were 12 to 14 years old. In our series we encountered no children.

Love and Rivers found 29 patients with symptoms indistinguishable from a disc herniation syndrome, accounting for a 5.6% incidence in their series published in 1962 [8]. The most common tumor was neurofibroma, with 11 cases. They speculated that tumor-induced compression of the long sensory tracts of the spinal cord can mimic signs and symptoms of lumbar disease. In another paper, the same authors presented seven patients in whom both an intraspinal tumor and a protruded disc were present. Four of these were operated on for the disc herniation and had a pain-free interval, but they ultimately returned for further investigation [9]. Based on our experience with this small series, we recommend first treating the tumor, rather than the degenerative process, if both pathologies could be responsible for the patients problems.

Epstein et al. described three patients with thoracic spinal cord tumors also presenting with primary signs and symptoms of lumbar spine disorders. As the authors were performing total myelography in all their cases of lumbar disc disease at that time (1979), they were able to detect the tumors in all cases. In all patients, the symptoms of low back pain and lumbar radiculopathy improved after surgery for the tumors [5].

Conclusions

Although clinical symptoms and radiological investigation may suggest degenerative spine disease as the cause of back or neck pain and radicular complaints or myelopathy, there is a subgroup of patients with unexpected spinal tumors. In this contemporary series we found that 0.5% of patients with symptoms and radiological evidence of degenerative spine disease turned out to have a spinal tumor responsible for their complaints. MRI was the most helpful diagnostic tool to identify the lesions, which were often situated at a considerable distance from the degenerative process. Tumor extirpation successfully controlled the clinical symptoms in all cases, with only one patient treated for both conditions.

Typical settings that should raise suspicion are back pain exacerbated by the recumbent position, persistent pain after disc surgery, and any severe discordance between clinical presentation and the presumed radiological diagnosis.

References

- 1.BeniniOrthopade 199928916. 10.1007/s00132005041610602827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camins MB, Oppenheim JS, Perrin RG (1996) Tumors of the vertebral axis: benign, primary malignant, and metastatic tumors. In: Youmans JR (ed) Neurological surgery, vol 4. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 3134–3167

- 3.Daneyemez Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1999;42:63. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dugas Orthopedics. 1986;9:253. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19860201-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.EpsteinSpine 19794121264028 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg MS (1994) Handbook of neurosurgery, 3rd edn. Greenberg Graphics, Lakeland, Fla, pp 177–180

- 7.GuyerSpine 1988133283388119 [Google Scholar]

- 8.LoveNeurology 1962126014466875 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Love JAMA. 1962;160:528. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattle Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1986;116:1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappas Neurosurgery. 1992;30:862. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapoport Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1994;15:189. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(05)80072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezai AR, Lee M, Abbott R (1998) Benign spinal tumors. In: Engler GL, Cole J, Merton WL (eds) Spinal cord disease: diagnosis and treatment. Dekker, New York, pp 287–313

- 14.Rothman Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1994;15:226. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(05)80073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schramm Neurochirurgia. 1977;20:22. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1090351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wassmann H, Böker DK, Neumann J (1984) Tumorbedingtes lumbales Bandscheibensyndrom. In: Hohmann D, Kügelken B, Liebig K, Schirmer M (eds) Neuroorthopädie 2. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 294–299