Abstract

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory disease marked by intra-articular decreases in pH, aberrant hyaluronan regulation and destruction of bone and cartilage. Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) are the primary acid sensors in the nervous system, particularly in sensory neurons and are important in nociception. ASIC3 was recently discovered in synoviocytes, non-neuronal joint cells critical to the inflammatory process.

Objectives

To investigate the role of ASIC3 in joint tissue, specifically the relationship between ASIC3 and hyaluronan and the response to decreased pH.

Methods

Histochemical methods were used to compare morphology, hyaluronan expression and ASIC3 expression in ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mouse knee joints. Isolated fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) were used to examine hyaluronan release and intracellular calcium in response to decreases in pH.

Results

In tissue sections from ASIC3+/+ mice, ASIC3 localised to articular cartilage, growth plate, meniscus and type B synoviocytes. In cultured FLS, ASIC3 mRNA and protein was also expressed. In FLS cultures, pH 5.5 increased hyaluronan release in ASIC3+/+ FLS, but not ASIC3−/− FLS. In FLS from ASIC3+/+ mice, approximately 50% of cells (25/53) increased intracellular calcium while only 24% (14/59) showed an increase in ASIC3−/− FLS. Of the cells that responded to pH 5.5, there was significantly less intracellular calcium increases ASIC3−/− FLS compared to ASIC3+/+ FLS.

Conclusion

ASIC3 may serve as a pH sensor in synoviocytes and be important for modulation of expression of hyaluronan within joint tissue.

INTRODUCTION

Decreases In pH occur in a variety of inflammatory exudates, including those from people with rheumatoid arthritis, and can reach as low as pH 5.4.1,6 The severity of pain and joint damage correlates with the degree of acidity in synovial fluid from arthritic joints.1,7 The primary acid sensors in peripheral tissues are acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs).8 The expression of ASICs in the peripheral and central nervous system is pivotal to their role in a variety of disease states including: multiple sclerosis, musculoskeletal pain, learning and memory disorders, and anxiety.9,12 In accord, we have shown that ASIC3−/− mice exhibit reduced hyperalgaesia compared to ASIC3+/+ mice.10,13 There is also increased expression of ASIC3 in primary afferent fibres innervating the joint, and in retro-gradely labelled dorsal root ganglia in response to joint inflammation.14Multiple investigators report the expression of ASICs in non-neuronal cells: monocytes, arthritic chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteoclasts, carotid body glomus cells, nucleus pulposus cells and muscle cells,15,18 suggesting diverse roles for ASICs. These findings are of particular interest as we recently demonstrated ASIC3 protein in synoviocytes.13

Synoviocytes are responsible for maintaining homeostasis by secreting lubricating synovial fluid into, and absorbing waste from, the joint cavity. Type A synoviocytes are of macrophage lineage and act to phagocytose joint cavity debris and waste; while type B synoviocytes, derived from fibroblasts, secrete the protective synovial fluid into the joint cavity.19,20 The two cell types synchronously work to maintain proper synovial fluid balance, a regulation which is crucial in protecting the joint from destruction inherent in inflammatory disease.21 Of the synovial fluid constituents, hyaluronan is the most abundant22 and in articular cartilage, forms a cushion for the joint.23 Increased synthesis of hyaluronan occurs in response to mechanical stretch of intact joints24 and from cultured fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS).25,26 Further, proinflammatory cytokines or nitric oxide donors also induce a rapid increase in hyaluronan production in cultured FLS.27,23 Thus, hyaluronan plays a critical role in normal function of the joint, as well as after joint inflammation.

The purpose of the current study was to determine the functional role of ASIC3 in synoviocytes and to test the hypothesis that ASIC3 acts as a pH sensor in these non-neuronal cells. We, therefore, examined localisation of ASIC3 in joint tissues, responses of synoviocytes to decreases in pH and interactions of ASIC3 with hyaluronan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All experiments were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Congenic ASIC3−/− and ASIC3+/+ mice on a C57Bl/6J background29 were bred at the University of Iowa Animal Care Facility. Male mice, 9–10 weeks of age, were used in these studies.

Isolation and culturing of fibroblast-like synoviocytes

FLS were isolated from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice according to previously published methods30 (see supplementary material).

Cell and tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry (figures 1–5)

FLS were plated onto chamber slides at 24 000 cells/well (see supplementary material) incubated 2 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented media, serum starved for 24 h and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, 15 min, room temperature (figure 2). Two different protocols for tissue collection were used (figures 1, 3–5). The 20 µm cryosections in figure 1 were obtained by removal of the anterior synovial tissue, which was snap frozen at −160°C and postfixed on the slide with 2% paraformaldehyde. Figures 3–5 were obtained by perfusing mice with 4% paraformaldehye and, removal of the whole leg, prior to decalcification. Sections were cryosectioned at 14 µm (see supplementary material). For hyaluronan and immunohistochemical staining, sections were obtained and tested from ASIC3+/+ (n=6) and ASIC3−/− mice (n=6).

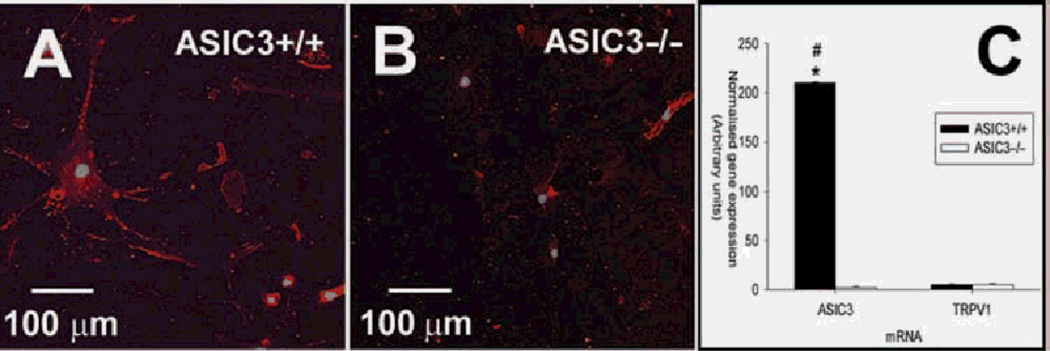

Figure 2.

Cultured synoviocytes express acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) protein and mRNA. A,B. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) were fixed and stained with an antibody to ASIC3 (red). Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO3 (blue). The FLS of (A) and (B) were derived from ASIC3 +/+ and ASIC3−/−, respectively. C. Quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of ASIC3 and TRPV1 mRNA expression in FLS cultures. Normalised gene expression (arbitrary units) for ASIC3 and TRPV1 mRNA is plotted for ASIC3+/+ (black bars) and ASIC3−/− (white bars) FLS cultures. Quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR data were normalised with GAPDH mRNA levels. Each bar represents 12 measurements. *Significantly different from ASIC3−/− ; +significantly different from TRPV1 mRNA. Data are mean±SEM.

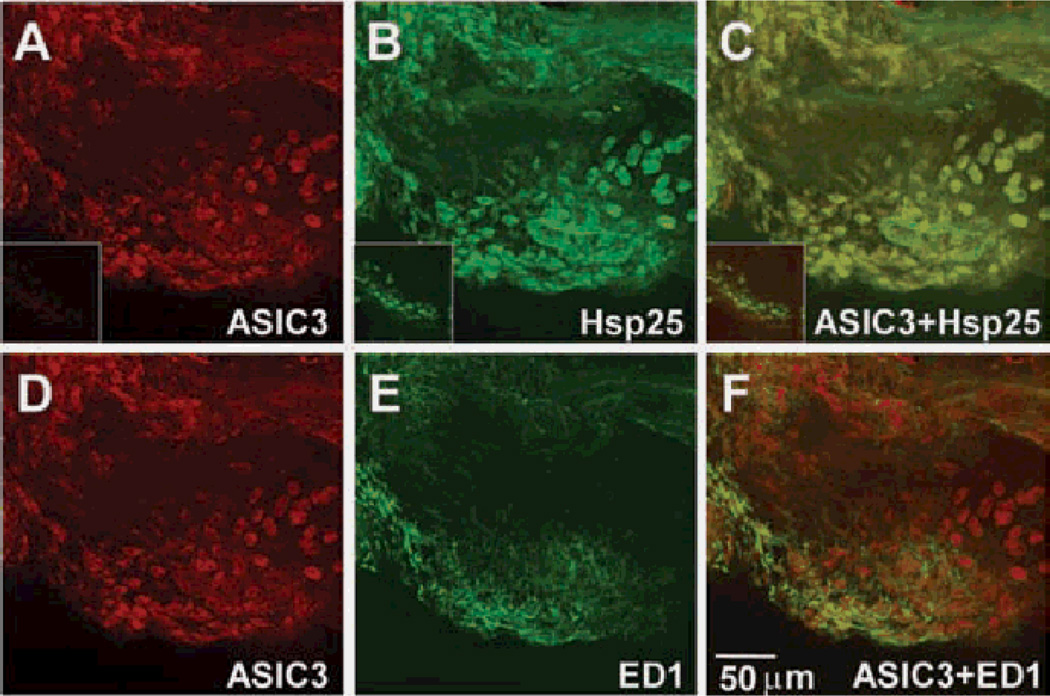

Figure 1.

Acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) is located in type B, but not type A synoviocytes. Whole mount preparations of anterior synovium from an ASIC3+/+ mouse knee joint, were double labelled for ASIC3 (red; A,D), and either the type B synoviocyte marker, heat shock protein 25 (Hsp25) (green; B) or the type A marker, ED1 (green; E). C. Merged image of ASIC3 (A) and Hsp25 (B), and shows colocalisation of ASIC3 protein with Hsp25. F. Merged image of ASIC3 (D) and ED1 (E). The insets of (A) and (B) show the staining of whole mount anterior synovium of ASIC3−/− mice with ASIC3 and Hsp25 antibodies, respectively. The inset of (C) is the overlay of the (A) and (B) insets.

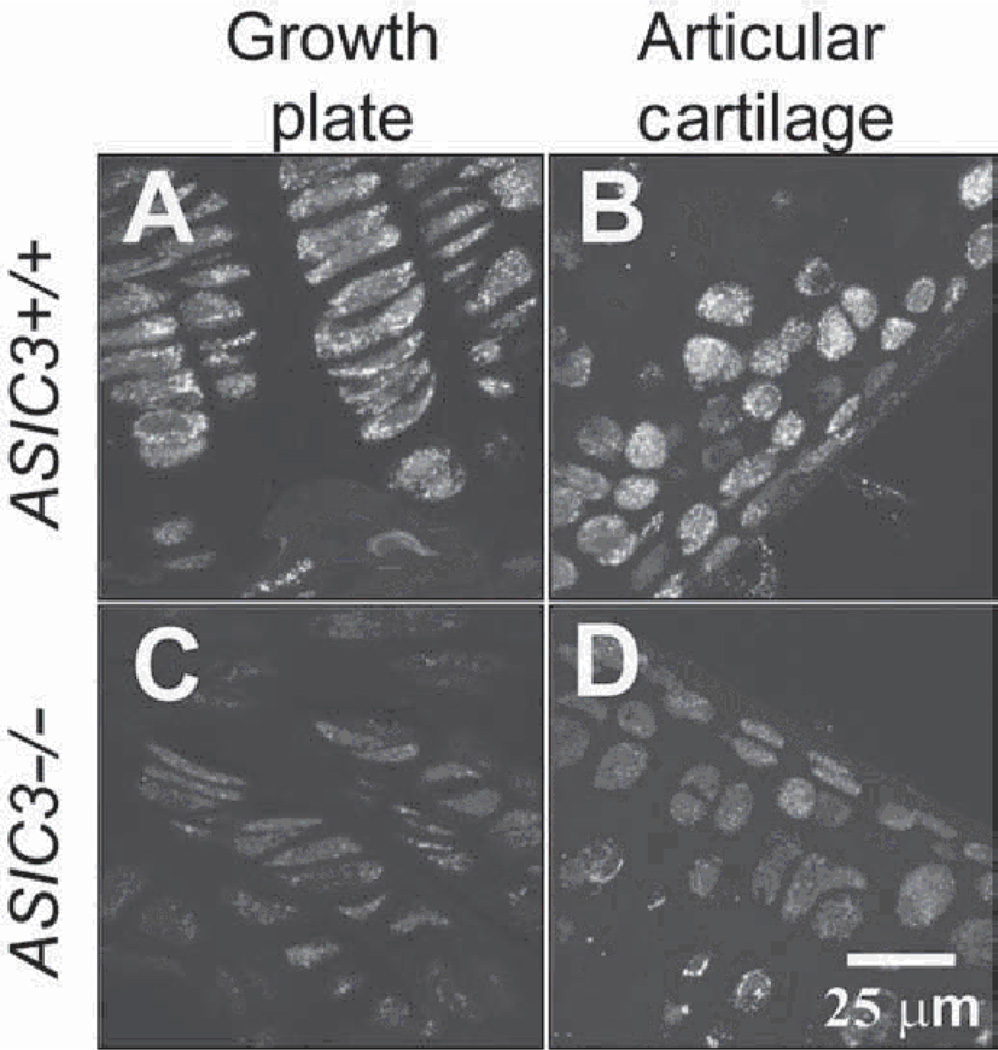

Figure 3.

Acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) immune-reactivity is found in cartilaginous structures of the knee joint. Sagittal sections through legs from [A,B)ASIC3+/+ and [C,D)ASIC3−/− mice were immunohistochemically stained for ASIC3. Immunoreactivity for ASIC3 was found in epiphysial cells of the femoral growth plate (A) and in the femoral articular cartilage (B) in ASIC3+/+ mice. No staining is seen in the corresponding tissue of ASIC3−/− mice (C,D). See supplementary material for colour images.

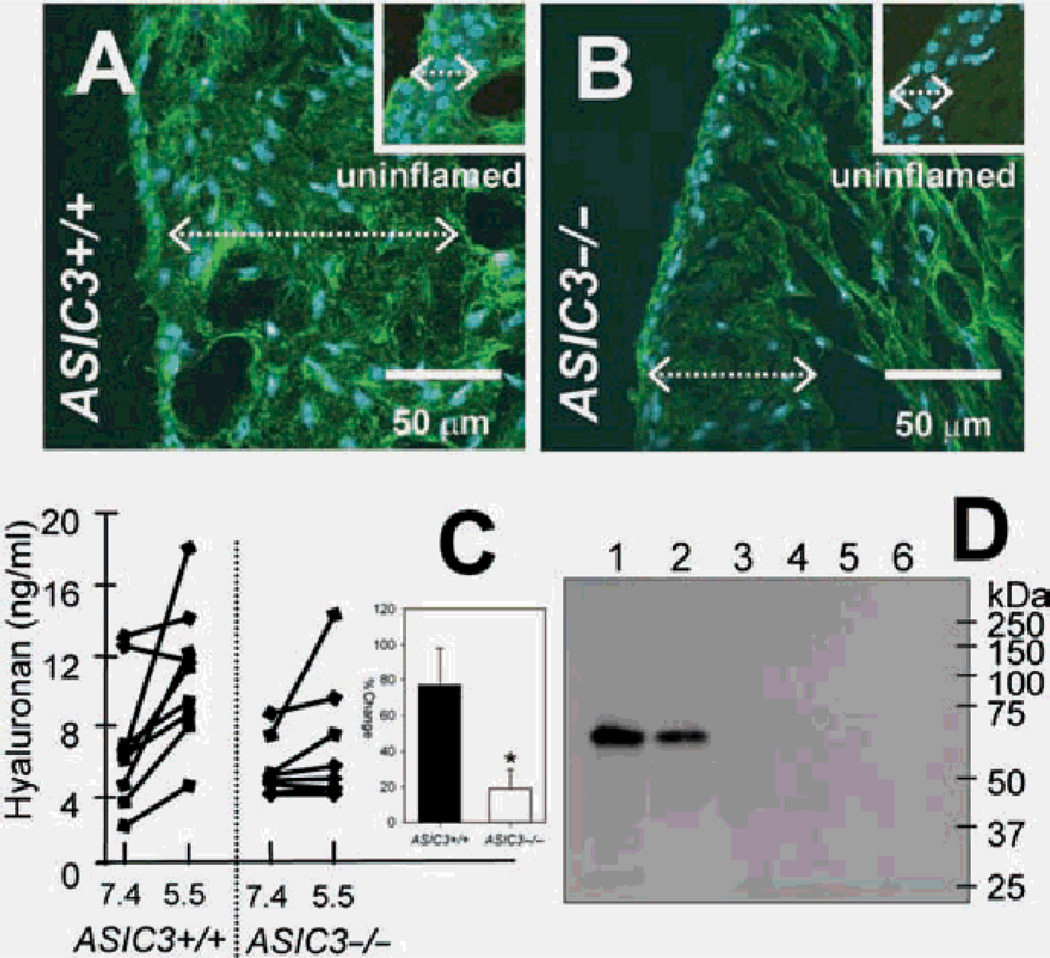

Figure 5.

Hyaluronan expression after inflammation and release in response to decreases in pH are reduced in ASIC3−/− mice. Sagittal sections of whole leg segments through the knee joints of ASIC3+/+ (A) and ASIC3−/− (B) mice 24 h after carrageenan induced inflammation, were stained for hyaluronan, green. The cell nucleus is depicted in blue. For comparison, the insets of (A) and (B) show uninflamed synovium cropped from the images in figure 4A and E, respectively. Note the increase in the thickness of the synovium after inflammation synovium from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− tissues (dotted white line/double arrows). Hyaluronan expression is increased in the inflamed synovium of ASIC3−/− (B) mice compared to the uninflamed ASIC3−/− synovium (inset, B) but still appears less than either inflamed (A) or uninflamed (inset, A)ASIC3+/+ synovium. (C) Supernatants of fibroblast-like synoviocyte (FLS) cultures exposed 1 h to pH 5.5 show increases in hyaluronan concentration compared to control conditions exposed to pH 7.4. Inset shows the percentage increased release of hyaluronan in ASIC3+/+ (n=9) was significantly greater than that from ASIC3−/−(n=8) mice (p<0.05). Data are mean±SEM. (D) Lysates containing haemagglutin-tagged acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) incubated with either no hyaluronan (lane 3), or biotinylated hyaluronan, high molecular weight (lane 4), 74 K (lane 5) and 12 K (lane 6). None of the hyaluronans interacted with ASIC3. The precleared lysate alone shows expression of ASIC3 (lane 1). The haemagglutin-tagged ASIC3 protein did not directly bind Neutravidin beads (unbound fraction, lane 2).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was carried out using rabbit polyclonal antibodies for ASIC3 (1:500; Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel) and heat shock protein (Hsp)25 (1:500; Stressgen, Ann Arbor, Minnesota, USA), and mouse anti-rat ED1 (1:250; AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) using standard procedures (see supplementary material). For double labelling, antibodies were checked by omitting either antibody; results confirmed that there was no crossreactivity. Hyaluronan was stained using biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (bHABP; 4 µg/ml; Northstar Bioproducts, East Falmouth, Massachusetts, USA). Nuclear staining was with TO-PRO3 (1:5000, 20 min; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). After blocking, tissue was incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies included donkey anti-mouse Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA), biotinylated goat anti-rabbit Jackson ImmunoResearch), streptavidin Alexa568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa647 (Invitrogen). Images of fluorescent stained sections were collected with an MRC-1024 confocal imaging system. Multiple images (3–5) per animal were examined to confirm immunohistochemistry results. All staining procedures included ‘no primary’ controls to confirm that there was no non-specific binding of the secondary antibody.

Quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR

FLS of ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice used in RNA analyses were between passages 2 and 5 and at >90% confluence using standard procedures (see supplementary material). Total RNA was extracted from the FLS cell pellet using the RNeasy mini purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). First strand cDNA was synthesised from 1 µg of each RNA sample using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). All PCRs were performed with known dilutions of rodent cDNA to allow construction of a standard curve relating cycle threshold to template copy number. ASIC3 (Mm00805460_ml), transient receptor potential vaniiloid-1 ion channel (TRPV1) (Mm01246282_s1) and the mouse control assay for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, California, USA). Relative quantities of gene expression were determined by comparing relative cycle thresholds, normalised to GAPDH.

Knee joint inflammation

Knee joint inflammation was induced by injecting 20 µl of 3% carrageenan dissolved in sterile saline into the left knee joint cavity while the mice were briefly anesthetised with isofluorane (3%). At 24 h after injection mice were killed, transcardially perfused and tissue removed for immunohistochemistry.

ASIC3 binding to hyaluronan

Cultured Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells, which do not express endogenous ASIC3, were transfected with hae-magglutinin-tagged mouse ASIC3 cDNA (15 µg/106 cells) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) and cell lysates were harvested 48 h after transfection for immunoprecipitation experiments (see supplementary material). Lysates were incubated with either biotinylated rooster comb hyaluronic acid (HA), biotinylated HA-74KDa, biotinylated HA-12KDa or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h, and then incubated with Neutravidin sepharose beads for an additional 3 h at 4°C. Biotinylated material was collected, the beads washed with lysis buffer, and eluted with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer. Samples were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with anti-haemagglutinin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate monoclonal antibody and developed with the ECL Plus western detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Additional experiments were also conducted to assess binding (see supplementary material).

Quantitative hyaluronic acid assay

pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 external physiological pH solutions used for the hyaluronic assay and calcium imaging were prepared according to previously published procedures 31 (see supplementary material). FLS cultures plated at 100 000 cells/well (ASIC3+/+ n=9; ASIC3−/− n=8) were exposed to either pH 7.4 or pH 5.5 for 60 min. Supernatants were removed, and assayed in triplicate for hyaluronan concentration (Corgenix, Denver, Colorado, USA) (see supplementary material).

Calcium imaging

Cells were plated with 30 000 cells/dish (6-well plate), loaded with cell permeant Oregon Green Bapta-1 AM (OGB-1) in pH 7.4 for 1 h. Either pH 5.5 or 30µM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) was introduced into the culture dish using a syringe pump. Fluorescence was measured 15 s before, 69 s during and 10 s after application of pH 5.5, or CPA on an Olympus 1X81 motorised inverted microscope (Leeds Precision Instruments, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Percentage change in fluorescence intensity at a given time point was calculated as follows: %ΔF−(F–F0)/F0*100, where F is current fluorescence intensity and F0 is fluorescence intensity under control conditions (pH=7.4).

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as mean±SEM. Data were analysed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the RT-PCR and hyaluronan assay. For measurement of calcium imaging repeated measures ANOVA compared values between responses in FLS from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice, and a t test compared the area under the curve differences in FLS from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice. The χ2 test was used to calculate differences between the number of responders in ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice. p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ASIC3 is expressed in type B synoviocytes

In knee joint synovium from ASIC3+/+ mice, ASIC3 colocalised with the fibroblast (type B) marker, Hsp2520 (figure 1A–C) but not with the macrophage (type A) marker ED-120 (figure ID–F). Further, ASIC3 staining did not occur in synovium from ASIC3−/− mice (figure 1A, inset).

In cultured FLS from ASIC3+/+ mice, immunostaining confirmed the presence of ASIC3 protein in FLS (figure 2A); ASIC3 staining was absent in FLS from ASIC3−/− mice (figure 2B). Analysis of mRNA from ASIC3+/+ FLS showed abundant expression of ASIC3 mRNA (figure 2C). Because FLS express the TRPV1 channel where it has been shown to be activated by decreases in pH,32,33 we compared the relative expression of TRPV1 and ASIC3 mRNA in ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− FLS. TRPV1 mRNA was detected in similar quantities in FLS from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice, but its expression was 40-fold less than that of ASIC3 in the ASIC3+/+ FLS.

ASIC3 is expressed in cartilage

To examine ASIC3 expression in other joint tissues, we prepared tissue sections from whole leg segments and immunohistochemically stained for ASIC3. ASIC3 was expressed in articular cartilage and growth plate of the tibia and femur of ASIC3+/+ mice figure 3A,B). No ASIC3 immunoreactivity was observed in the subchondral bone. Immunoreactivity was negative in the corresponding tissue of ASIC3−/− mice (figure 3C,D).

ASIC3 modulates the expression and release of hyaluronan

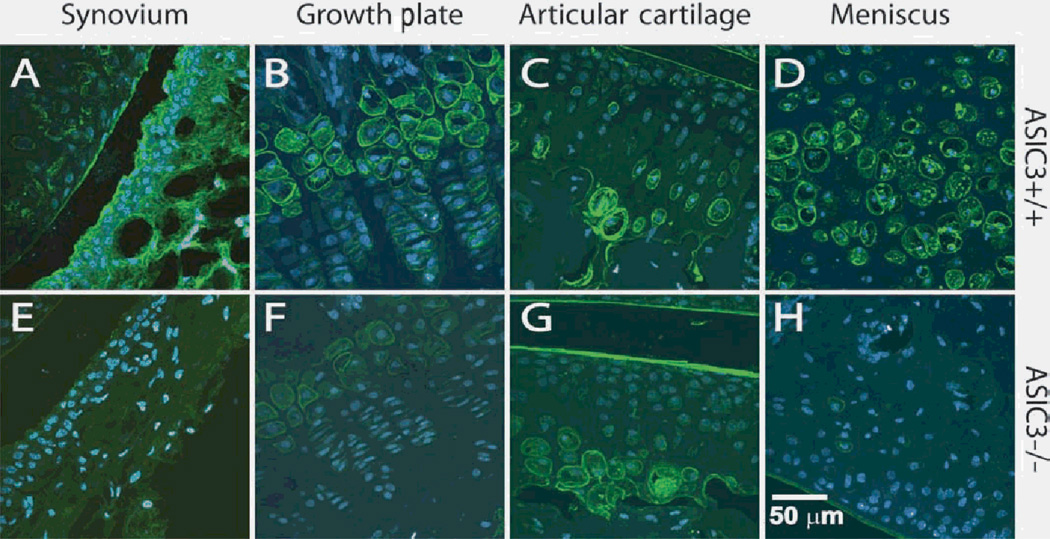

In tissue sections from whole leg segments, there was decreased hyaluronan staining in ASIC3−/− mice when compared to ASIC3+/+ mice. This reduction in hyaluronan staining occurred in the synovium, growth plate, articular cartilage and meniscus in animals without inflammation (figure 4). Since synoviocytes rapidly alter the amount of hyaluronan secreted upon inflammation,34 we examined the degree of hyaluronan staining in the synovium 24 h after carrageenan was injected into the knee joint cavity. At 24 h after inflammation the thickness of the synovium was increased in tissue from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice (figure 5A,B). This increased thickness is a result of increased connective tissue without an increase in the number of cells. After inflammation, hyaluronan expression increases in ASIC3+/+ mice (figure 5B and inset). However, hyaluronan expression in the synovium from ASIC3−/− 24 h after inflammation is less than either uninflamed or inflamed synovium from ASIC3+/+ mice (figure 5A,B and insets).

Figure 4.

Hyaluronan expression is decreased in knee joint structures from ASIC3−/− mice compared to tissues from ASIC3+/+ mice. Sagittal sections stained for hyaluronan (green; blue = nuclear dye TO-PRO3) in whole leg segments from ASIC3+/+ (A–D) and ASIC3−/− (E,F)mice. Hyaluronan staining is reduced in the synovium (A,E), the epiphysial cells of the femoral growth plate (B,F), the femoral articular cartilage (C,G) and in the meniscus (D,H) of ASIC3−/− mice when compared to staining in ASIC3+/+ mice.

To confirm and quantify the regulation of hyaluronan by ASIC3, we next tested if acidic pH altered the amount of hyaluronan released from cultured FLS from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice. The average amount of HA released from ASIC3+/+ FLS under acidic conditions (10.94 ng/ml) was greater than that released under physiological pH (6.99 ng/ml) (p<0.05) figure 5C).

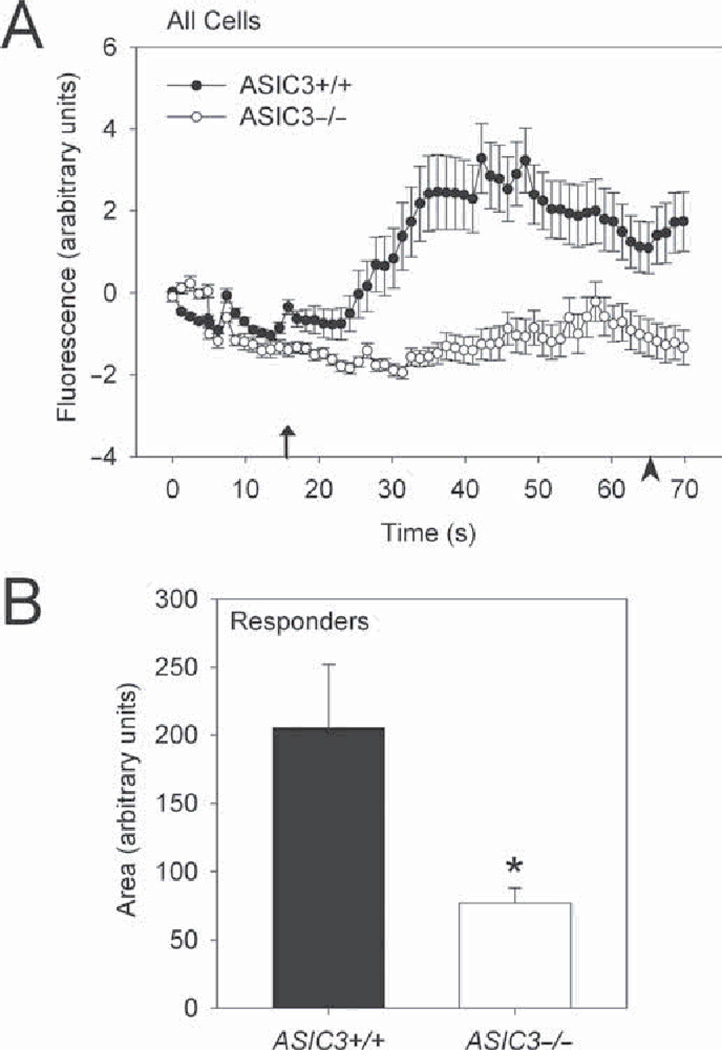

Decreases in pH increase intracellular calcium release in FLS through ASIC3

Because a rapid increase in intracellular calcium is indicative of signalling pathway activation,35,36 and ASICs are permeable to Ca2+ and are activated by decreases in pH,8 we monitored changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i in cultured FLS from ASIC3+/+ and ASIC3−/− mice in response to pH 5.5. As a control, application of CPA, a sarcoplasmic reticulum pump inhibitor, increased [Ca2+]i which indicated viable and loaded FLS (see supplementary material). In response to pH 5.5, there was a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i in almost half of ASIC3+/+ FLS (25 of 53 cells) (figure 6), when compared to pH 7.4. In contrast, only 24% of ASIC3−/− FLS (14 of 59 cells) responded to pH 5.5 with a rise in [Ca2+]i (p<0.001) (figure 6). Of those that responded to pH 5.5 there was a smaller increase in [Ca2+]i in FLS from ASIC3−/− mice compared to those from ASIC3+/+ mice (*p=0.0001). Quantification of the area under the curve showed that [Ca2+]i elevations of cells that responded to pH 5.5 was less in ASIC3−/− FLS compared to ASIC3+/+ FLS (p=0.0001) figure 6).

Figure 6.

Increased calcium release in response to decreases in pH is reduced in ASIC3−/− mice. A. Time course profile of all cells for the percentage change in [Ca2+]i from baseline for ASIC3 +/+ fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) and ASIC3−/− FLS in response to (arrow indicates pH or cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) application). *Significantly different from ASIC3+/+ (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)). Data are mean±SEM. B. The area under curve for each responding FLS, shows a statistically significant difference between groups (p=0.0001, t test). Data are mean±SEM. See supplementary material for more calcium imaging results.

ASIC3 does not bind to the extracellular matrix component, hyaluronan

Because degerin (DEG)/epithelial Na(+) channels (ENaC) family members can bind extracellular proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans37,42 and ASICs contain putative, hyaluronan binding motifs in their extracellular domain, we examined whether ASIC3 would bind to hyaluronan in vitro. Binding of ASIC3 and hyaluronan was examined with lysates from CHO-K1 cells expressing haemagglutinin-tagged ASIC3 (figure 5D). Immunoprecipitation, conducted by incubating the protein lysate with biotinylated hyaluronan and subsequently with Neutravidin beads, showed that no precipitate contained the haemagglutinin-tagged ASIC3, indicating a lack of binding (figure 5D).

DISCUSSION

ASIC3 serves as a pH sensor in non-neuronal cells

The current study shows expression of ASIC3 in type B FLS, chondrocytes and the epiphysial plate from ASIC3+/+ mice. Importantly, no immunostaining for ASIC3 was detected in tissues from ASIC3−/− mice, serving as a negative control. These data extend prior studies that show expression of ASIC3 in non-neuronal joint cells15 including synoviocytes 24 by showing protein in joint tissue and mRNA in FLS of ASIC3+/+ mice.

Decreases in pH occur in a variety of inflammatory exudates, including those from people with rheumatoid arthritis and this pH decrease correlates with severity of joint destruction and pain.1,7 ASICs detect decreases in pH with ASIC3 being most sensitive in the physiological range. Increases in intracellular calcium, which regulate activity of intracellular pathways, occur upon activation of a variety of ion channels, including N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, cholinergic receptors, or ATP receptors on synoviocytes, each of which can modulate production of inflammatory mediators32,43,46 In neuronal cells, proton activation of ASICs increase intracellular calcium47,48 and ASICla gates calcium directly.49 In FLS, activation of TRPV132,33 and a G-protein-coupled receptor50 by protons also increases [Ca2+]i, suggesting ASIC3 is not the sole pH sensor in FLS. However, we show a 40-fold greater expression of ASIC3 over TRPV1 mRNA in FLS; and ASIC3−/− FLS are less likely to be activated by protons than ASIC3+/+ FLS, despite equal expression of TRPV1 mRNA. In agreement with the current study, human FLS, isolated from patients with inflammatory arthropathies or tumour derived, increase [Ca2+]i in response to low pH.46 These findings suggest that pH modulates FLS activity and that ASIC3 is a prominent pH sensor in the synoviocytes.

FLS play a crucial role in enhancement of the inflammatory process,51 are a major source of cytokines and are the primary producers of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in rheumatoid arthritis. Recent data in cadherin-11−/− mice confirm that FLS contribute to the inflammatory component of arthritis as well as cartilage degradation.52 As decreases in pH are associated with inflammation, it is reasonable to assume that inflammatory mediators, such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) or Interleukln 1 (IL1), could sensitise the pH response in FLS. In sensory neurons, application of inflammatory mediators induces an upregulation of ASIC1, ASIC2 and ASIC3 mRNA in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) suggesting inflammatory mediators can modulate expression of ASICs in DRG.53,54 Recently, we confirmed an upregulation of ASIC3 protein and mRNA in sensory neurons after carrageenan-induced inflammation. 14,55 In synoviocytes, a similar process is likely to occur. For example, in FLS, the heat sensor TRPV1 shows an enhanced responsiveness to increases in temperature and an increase in expression after prior treatment with TNFα.56 Thus, future experiments should investigate an interaction between inflammatory mediators and the pH response in FLS.

While pH can reach as low as 5.4 in some disease conditions, the pH is commonly between 6.0 and 6.9 after inflammatory arthritis. Our study used pH 5.5 as the test stimulus for examining the role of ASICs in decreases in pH because prior published studies examining pH effects in synoviocytes showed the greatest effect with pH 5.5.50 In sensory neurons, routine electrophysiological studies of ASICs and pH show that responses to pH occur in a dose-dependent manner with the greatest effect occurring around pH 5.0.57 Future experiments should examine the pH response effect across multiple acidic pHs to determine the role of ASIC3 at all of these ranges.

ASIC3 modulates expression and release of hyaluronan

There was a decrease in hyaluronan staining in joint structures, synovium and cartilage, from ASIC3−/− mice compared to ASIC3+/+ mice. We also show increased hyaluronan release in FLS in response to decreases in pH and that this release is dependent on the presence of ASIC3. FLS secrete hyaluronan in response to the inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL1β, and interferon γ and to mechanical stimulation.27 Further, in FLS, activation of TRP channels, NMDA, cholinergic and ATP receptors modulates the production of inflammatory mediators.32,43,46 Our data suggests a direct or intermediate role for ASIC3 to modulate hyaluronan release to the inflammation-induced decrease in pH, making it a potential target in prevention of inflammatory induced joint destruction.

It is possible that ASIC3 could interact with hyaluronan in the extracellular domain of the channel. The extracellular domains of ASICs are large, encompassing the majority of the channel.58 Several ligands interact with the extracellular domain including calcium, lactate, arachidonic acid and redox reagents. As ASICs are vertebrate homologues of the mechanosensitive DEG/ENaC channels in C elegans, they could act in mechanotransduction, or respond to mechanical stimuli. Binding of the extracellular domain of ASICs to extracellular components, could functionally form a tether to physically open the channel.59 The extracellular domain of ASIC3 contains a sequence (amino acids 382–398 of mouse ASIC3, accession number Q6X1Y6, NCBI Entrez protein database) that is consistent with potential receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility (RHAMM)-like binding motifs for hyaluronan.60,61 However, the current data show no binding of hyaluronan to ASIC3.

Conclusions

In summary, the current study shows expression of ASIC3 in FLS and chondrocytes in adult tissue from ASIC3+/+ mice and not from ASIC3−/− mice. Alterations in hyaluronan expression occur in ASIC3−/− mice suggesting that ASIC3 plays a significant role in joint function. Decreases in pH activate FLS by increasing intracellular calcium and releasing hyaluronan. We conclude that ASIC3 in non-neuronal joint cells regulates pH responsiveness and controls release of the extracellular matrix polysaccharide hyaluronan. We propose ASIC3 as a potential therapeutic target not only to treat the symptoms of pain associated with diseases of the joint, but more significantly, to attenuate the underlying causes of such diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Central Microscopy Facility especially Chantal Allamargot for training on the CryoJane System and Tom Moninger for calcium imaging advice. We thank Dr Christopher Benson for use of tissue culture facilities and Anne Harding for cell culturing assistance.

Funding This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 AR053509, AR053509-S1, R01 AI067752, R01 AI070555, R01 AR047825.

Footnotes

Additional data [supplementary methods and supplementary figures) are published online only at http://ard.bmj.com/content/vol69/issue5

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geborek P, Saxne T, Pettersson H, et al. Synovial fluid acidosis correlates with radiological joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis knee joints. J Rheumtol. 1989;16:468–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldie I, Nachemson A. Synovial pH in rheumatoid knee joints. II. The effect of local corticosteroid treatment. Acta Orthop Scand. 1970;41:354–362. doi: 10.3109/17453677008991521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldie I, Nachemson A. Synovial pH in rheumatoid knee-joints. I. The effect of synovectomy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1969;40:634–641. doi: 10.3109/17453676908989529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habler C. Untersuchungen zur molekularpathologie der gelenkexsudate und ihre klinischen ergebnisse. Arch Klin Chir. 1930;156:20–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habler C. K+ und Ca2+ -gehalt von eiter und exsudaten und seine beziehungen zum entuzundungschmerz. Arch Klin Wochenschr. 1929;8:1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jebens EH, Monk-Jones ME. On the viscosity and pH of synovial fluid and the pH of blood. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1959;41-B:388–400. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.41B2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revici E, Stoopen E, Frenk E, et al. The painful Focus. II. The relation of pain to local physiochemical changes. Bull Inst Appl Biol. 1949;1:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wemmie JA, price MP, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channels: advances, questions and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friese MA, Craner MJ, Etzensperger R, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel-1 contributes to axonal degeneration in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Med. 2007;13:1483–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sluka KA, Price MP, Breese NM, et al. Chronic hyperalgesia induced by repeated acid injections in muscle is abolished by the loss of ASIC3, but not ASIC1. Pain. 2003;106:229–239. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wemmie JA, Askwith CC, Lamani E, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 1 is localized in brain regions with high synaptic density and contributes to fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5496–5502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05496.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wemmie JA, Coryell MW, Askwith CC, et al. Overexpression of acid-sensing ion channel 1a in transgenic mice increases acquired fear-related behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeuchi M, Kolker SJ, Bumes LA, et al. Role of ASIC3 in the primary and secondary hyperalgesia produced by joint inflammation in mice. Pain. 2008;137:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeuchi M, Kolker SJ, Sluka KA. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 expression in mouse knee joint afferents and effects of carrageenan-induced arthritis. J Pain. 2009;10:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahr H, van Driel M, van Osch GJ, et al. Identification of acid-sensing ion channels in bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan ZY, Lu Y, Whiteis CA, et al. Acid-sensing ion channels contribute to transduction of extracellular acidosis in rat carotid body glomus cells. Circ Res. 2007;101:1009–1019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchiyama Y, Cheng CC, Danielson KG, et al. Expression of acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) in nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc is regulated by p75NTR and ERK signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1996–2006. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gitterman DP, Wilson J, Randall AD. Functional properties and pharmacological inhibition of ASIC channels in the human SJ-RH30 skeletal muscle cell line. J Physiol (Lond) 2005;562:759–769. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwanaga T, Shikichi M, Kitamura H, et al. Morphology and functional roles of synoviocytes in the joint. Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63:17–31. doi: 10.1679/aohc.63.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A, Nozawa-Inoue K, Amizuka N, et al. Localization of CD44 and hyaluronan in the synovial membrane of the rat temporomandibular joint. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:646–652. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Firestein GS. Biomedicine. Every joint has a silver lining. Science. 2007;315:952–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1139574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt TA, Gastelum NS, Nguyen QT, et al. Boundary lubrication of articular cartilage: role of synovial fluid constituents. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:882–891. doi: 10.1002/art.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe H, Yamada Y, Kimata K. Roles of aggrecan, a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, in cartilage structure and function. J Biochem. 1998;124:687–693. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingram KR, Wann AK, Angel CK, et al. Cyclic movement stimulates hyaluronan secretion into the synovial cavity of rabbit joints. J Physiol (Lond) 2008;586:1715–1729. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Momberger TS, Levick JR, Mason RM. Hyaluronan secretion by synoviocytes is mechanosensitive. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momberger TS, Levick JR, Mason RM. Mechanosensitive synoviocytes: a Ca2+ − PKCalpha-MAP kinase pathway contributes to stretch-induced hyaluronan synthesis in vitro. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Morin-Robinet S, Lemarechal H, et al. Effects of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide donors on hyaluromc acid synthesis by synovial cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Sci. 2004;107:291–296. doi: 10.1042/CS20040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanimoto K, Ohno S, Fujimoto K, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines regulate the gene expression of hyaluronic acid synthetase in cultured rabbit synovial membrane cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2001;42:187–195. doi: 10.3109/03008200109005649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price MP, Mcllwrath SL, Xie J, et al. The DRASIC cation channel contributes to the detection of cutaneous touch and acid stimuli in mice. Neuron. 2001;32:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Acquisition, culture, and phenotyping of synovial fibroblasts. Methods Mol Med. 2007;135:365–375. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-401-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eshcol JO, Harding AM, Hattori T, et al. Acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) cell surface expression is modulated by PSD-95 within lipid rafts. Am J Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C732–C739. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00514.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kochukov MY, McNearney TA, Fu Y, et al. Thermosensitive TRP ion channels mediate cytosolic calcium response in human synoviocytes. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C424–C432. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00553.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu F, Sun WW, Zhao XT, et al. TRPV1 mediates cell death in rat synovial fibroblasts through calcium entry-dependent ROS production and mitochondrial depolarization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:989–993. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahl LB, Dahl IM, Engström-Laurent A, et al. Concentration and molecular weight of sodium hyaluronate in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other arthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:817–822. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.12.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen OH, Petersen CC, Kasai H. Calcium and hormone action. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:297–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berridge MJ. Cell signalling, A tale of two messengers. Nature. 1993;365:388–389. doi: 10.1038/365388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Schrank B, Waterston RH. Interaction between a putative mechanosensory membrane channel and a collagen. Science. 1996;273:361–364. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gu G, Caldwell GA, Chalfie M. Genetic interactions affecting touch sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6577–6582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Driscoll M, Tavernarakis N. Molecules that mediate touch transduction in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Gravit Space Biol Bull. 1997;10:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cueva JG, Mulholland A, Goodman MB. Nanoscale organization of the MEC-4 DEG/ENaC sensory mechanotransduction channel in Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14089–14098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4179-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du H, Gu G, William CM, et al. Extracellular proteins needed for C. elegans mechanosensation. Neuron. 1996;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M. Molecular modeling of mechanotransduction in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:659–689. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flood S, Parri R, Williams A, et al. Modulation of interleukin-6 and matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes by functional ionotropic glutamate receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2523–2534. doi: 10.1002/art.22829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loredo GA, Benton HP. ATP and UTP activate calcium-mobilizing P2U-like receptors and act synergistically with interleukin-1 to stimulate prostaglandin E2 release from human rheumatoid synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:246–255. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199802)41:2<246::AID-ART8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caporali F, Capecchi PL, Gamberucci A, et al. Human rheumatoid synoviocytes express functional P2X7 receptors. J Mol Med. 2008;86:937–949. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waldburger JM, Boyle DL, Pavlov VA, et al. Acetylcholine regulation of synoviocyte cytokine expression by the alpha7 nicotinic receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3439–3449. doi: 10.1002/art.23987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Immke DC, McCleskey EW. Protons open acid-sensing ion channels by catalyzing relief of Ca2+ blockade. Neuron. 2003;37:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Light AR, Hughen RW, Zhang J, et al. Dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating skeletal muscle respond to physiological combinations of protons, ATP, and lactate mediated by ASIC, P2X, and TRPV1. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1184–1201. doi: 10.1152/jn.01344.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yermolaieva O, Leonard AS, Schnizler MK, et al. Extracellular acidosis increases neuronal cell calcium by activating acid-sensing ion channel 1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6752–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christensen BN, Kochukov M, McNearney TA, et al. Proton-sensing G protein-coupled receptor mobilizes calcium in human synovial cells. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C601–C608. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00039.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mor A, Abranson SB, Pillinger MH. The fibroblast-like synovial cell in rheumatoid arthritis: a key player in inflammation and joint destruction. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee DM, Kiener HP, Agarwal SK, et al. Cadherin-11 in synovial lining formation and pathology in arthritis. Science. 2007;315:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1137306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mamet J, Baron A, Lazdunski M, et al. Proinflammatory mediators, stimulators of sensory neuron excitability via the expression of acid-sensing ion channels. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10662–10670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10662.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voilley N, de Weille J, Mamet J, et al. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit both the activity and the inflammation-induced expression of acid-sensing ion channels in nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8026–8033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08026.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walder RY, Rasmussen LA, Rainier JD, et al. ASIC1 and ASIC3 play different roles in the development of hyperalgesia following inflammatory muscle injury. J Pain. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.004. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kochukov MY, McNearney TA, Yin H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) enhances functional thermal and chemical responses of TRP cation channels in human synoviocytes. Mol Pain. 2009;5:49. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benson CJ, Xie J, Wemmie JA, et al. Heteromultimers of DEG/ENaC subunits form H +-gated channels in mouse sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2338–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, et al. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiong ZG, Chu XP, Simon RP. Ca2+ -permeable acid-sensing ion channels and ischemic brain injury. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ziebell MR, Prestwich GD. Interactions of peptide mimics of hyaluronic acid with the receptor for hyaluronan mediated motility (RHAMM) J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2004;18:597–614. doi: 10.1007/s10822-004-5433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amemiya K, Nakatani T, Saito A, et al. Hyaluronan-binding motif identified by panning a random peptide display library. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1724:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]