Abstract

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is the most common muscle disease in children. Historically, DMD results in loss of ambulation between ages 7 and 13 years and death in the teens or 20s. In order to determine whether survival has improved over the decades and whether the impact of nocturnal ventilation combined with a better management of cardiac involvement has been able to modify the pattern of survival, we reviewed the notes of 835 DMD patients followed at the Naples Centre of Cardiomyology and Medical Genetics from 1961 to 2006. Patients were divided, by decade of birth, into 3 groups: 1) DMD born between 1961 and 1970; 2) DMD born between 1971 and 1980; 3) DMD born between 1981 and 1990; each group was in turn subdivided into 15 two-year classes, from 14 to 40 years of age. Age and causes of death, type of cardiac treatment and use of a mechanical ventilator were carefully analyzed.

The percentage of survivors in the different decades was statistically compared by chi-square test and Kaplan-Meier survival curves analyses. A significant decade on decade improvement in survival rate was observed at both the age of 20, where it passed from 23.3% of patients in group 1 to 54% of patients in group 2 and to 59,8% in patients in group 3 (p < 0.001) and at the age of 25 where the survival rate passed from 13.5% of patients in group 1 to 31.6% of patients in group 2 and to 49.2% in patients in group 3 (p < 0.001).

The causes of death were both cardiac and respiratory, with a prevalence of the respiratory ones till 1980s. The overall mean age for cardiac deaths was 19.6 years (range 13.4-27.5), with an increasing age in the last 15 years. The overall mean age for respiratory deaths was 17.7 years (range 11.6-27.5) in patients without a ventilator support while increased to 27.9 years (range 23-38.6) in patients who could benefit of mechanical ventilation.

This report documents that DMD should be now considered an adulthood disease as well, and as a consequence more public health interventions are needed to support these patients and their families as they pass from childhood into adult age.

Key words: Duchenne, survival, cardiomyopathy

Background

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is the most common inherited muscle disease in children. It is characterized by slow, progressive atrophy and muscle weakness, and by wasting of skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle (1, 2). It is inherited as an X-linked recessive disorder (Xp2.1), caused by mutations in the DMD gene on the X chromosome (3), which leads to the complete absence of the cytoskeletal protein dystrophin in both skeletal and cardiac muscle fibres (4).

Symptoms usually appear before age 6 but may appear as early as in infancy. They may include fatigue, muscle weakness, difficulty with motor skills (running, hopping, jumping), frequent falls, progressive difficulty in walking, learning difficulties (the IQ can be below 75) and mental retardation. Cardiac dysfunction is a frequent manifestation of DMD and a common cause of death (1, 5-7), as is also respiratory failure. Breathing difficulties usually start by the age of 20 (1, 8).

The diagnosis of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy is usually suspected on the basis of the physical examination, family history and laboratory tests (creatine kinase levels more than 100-200 times normal) and confirmed by genetic (9-12) or immuno-histochemical analysis (13, 14). Although respiratory failure in DMD is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality, there is inadequate awareness of its treatable nature. Advances (15-19) in the respiratory care of DMD patients have improved the outlook for these patients, and many caregivers have changed from a traditional non-interventional approach to a more intensive, supportive approach (20-22). Despite the availability of new technologies to assist patients with DMD, many families do not receive sufficient information regarding their options in diagnosis and management of respiratory insufficiency. Most part of the literature in medicine and neurology reports that DMD has still an unfavourable prognosis and a reduced life expectation, with death usually occurring at the beginning of adult life (20 years). This probably because no curative treatment is yet available. However this does not mean that DMD is an untreatable disease as surgery can be used to correct the deformities of the inferior limbs and scoliosis (23), mechanical ventilation – prevalently nocturnal – is beneficial for the treatment of the restrictive respiratory insufficiency (24-30) and treatment with steroids (deflazacort) and ACE-inhibitors is effective in improving muscle strength and the period of autonomous ambulation (31-36) and in preventing or improving cardiomyopathy (37-40).

The aim of the work was to determine to what extent the survival of DMD patients has improved over the past decades, and to quantify how the major forms of treatment, i.e. nocturnal ventilation, better management of cardiac involvement and administration of steroids have been able to modify the pattern of survival.

Patients and methods

To this aim, the notes of 835 DMD patients – followed at the Centre of Cardiomyology and Medical Genetics of the Second University of Naples from 1961 to 2006 – were retrospectively and systematically reviewed. The greatest part of the patients (80%) originated from the Campania Region; 15% from Southern and 5% from Northern and Central Italy.

The diagnosis of the disease, originally based on a typical family history and the pattern of inheritance, on increased values of serum creatine kinase, and on the dystrophic process as evidenced in muscle biopsies, was supported by genetic analysis since 1990. Treatment with steroids (deflazacort), ACE inhibitors and non-invasive mechanical ventilation was introduced in our Centre, as part of taking care of DMD patients, at the beginning of the 1990s.

Patients with incomplete notes or without routine follow-up at this Centre (145) and patients with a diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy not confirmed by molecular or immunohistochemical analysis (174) were excluded.

The remaining 516 patients – including familial cases where the molecular diagnosis was retrospectively assigned – were subdivided, by decade of birth, into 3 groups: 1) DMD born between 1961 and 1970; 2) DMD born between1971 and 1980; 3) DMD born between 1981 and 1990. We decided that a follow-up of at least 25 years was sufficient to include all patients who had already died. Age and causes of death were carefully analyzed, as well as the type of treatment performed (i.e. mechanical ventilation and/or pharmacological therapy). The study design was approved by the local ethical committee.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves were computed to determine median survival. SYSTAT software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) was used to calculate survival curves and to construct graphs for each group. The percentage of survivors among the three decades was statistically compared by chi-square test and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses.

Results

The study deals with the notes of 516 Duchenne patients. An analysis of familial versus sporadic cases, showed that the percentage of familial cases decreased (5) from the first two decades (59,6%) to the more recent one (20%), with a parallel increase in percentage of sporadic cases (from 38,5% to 75-80%). The differences were statistically significant (p < 0,001). This condition is probably the result of an effective genetic counselling introduced in our Centre since 1977.

Results of genetic analysis were available for 371 of 516 patients (71.8%); in 35 familial cases the molecular diagnosis was retrospectively assigned. As expected, deletions were the most frequent cause of mutations in DMD patients. They represented 69.3% of the cases, involving 1 to 33 exons, and were prevalently distributed into the gene hotspots (41-44). Duplications were found in 14.8% of DMD patients, while point-mutations were observed in 16% of patients (45). Taken together, we were able to identify dystrophin gene mutation in 406 out of 516 (78.7%) cases (46). In the remaining 110 patients, the diagnosis of DMD was confirmed by an immunohistochemical analysis that demonstrated the complete absence of dystrophin in the muscle fibers.

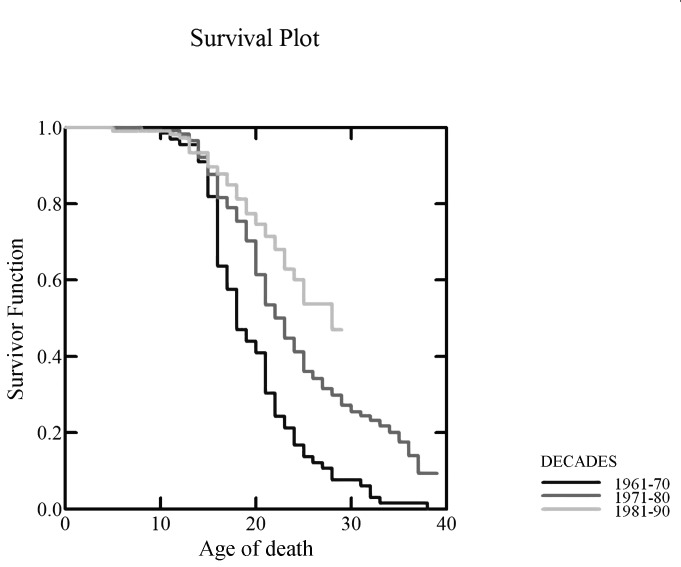

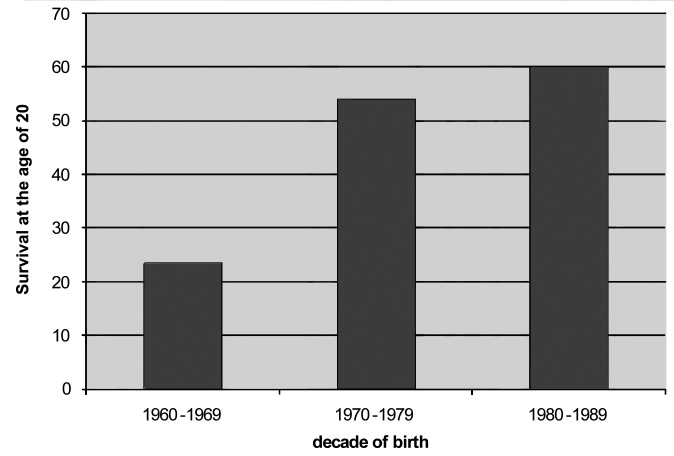

The curves of survival showed a decade on decade improvement in survival (Fig. 1). At the age of 20, the survival rate was 23.3% in DMD patients born in the 1960s, 54% in those born in the 1970s, and 59.8% in those born in the 1980s (Fig. 2), with log-rank tests showing a significant difference between the 3 survival curves (p < 0.001). At the age of 25, the survival rate was 13.5% in DMD patients born in the 1960s, 31.6% in those born in the 1970s, and 49.2% in patients born in the 1980s (p < 0.001). Of course, for the last decade, data are partial as they are limited to patients that are already 25 years of age.

Figure 1.

Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier) showing the survival decade from the 1960s to 1990s.

Figure 2.

Survival at 20 years, according to the decade of birth.

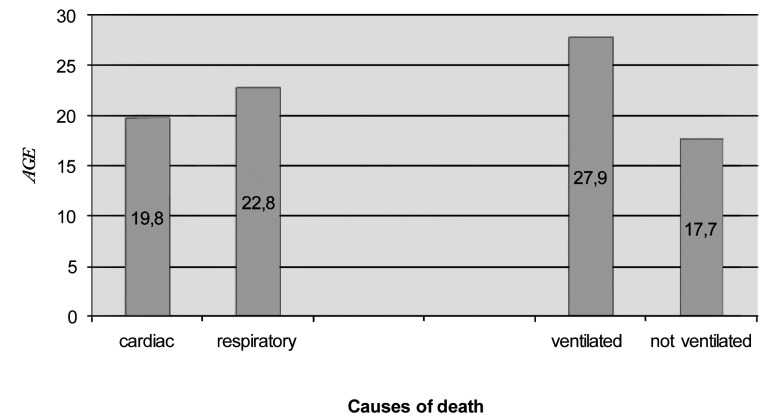

The causes of death were either cardiac or respiratory, with a prevalence of the respiratory causes till the 1980s. The overall mean age for cardiac deaths was 19.6 years (range 13.4-27.5).

An increase in the age of death for cardiac failure was observed in patients who died in the last 15 years. The overall mean age for respiratory deaths was 17.7 years (range 11.6-27.5) in patients without a mechanical ventilatory support. It increased to 27.9 years (range 23-38.6) in patients who could benefit from mechanical ventilation (Fig. 3). The differences are statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Causes of death in DMD patients. On the left the mean age for cardiac or respiratory causes is reported; on the right the mean age of death in ventilated versus non-ventilated patients.

Discussion

Duchenne muscular Dystrophy is considered a progressive disease with an unfavourable prognosis and a limited life expectancy, calculated at the beginning of the adult age (20 years). However in the last 10 years several groups have demonstrated an improvement of survival due to a more comprehensive therapeutic approach.

Eagle and co-workers (24), in reviewing in 2002 the notes of 197 DMD patients – whose treatment was managed at the Newcastle Muscle Centre from 1967 to 2002 – reported a significant decade on decade improvement in survival, with 14.4 years as mean age of death in the 1960s, and 25.3 years for those ventilated since 1990. In their series, cardiomyopathy significantly shortened life expectancy from 19 years to a mean age of 16.9 years. The authors concluded that a better coordinated care has been able to improve the chances of survival to 25 years, from 0% in the 1960s to 4% in the 1970s and to 12% in the 1980s. Nocturnal ventilation had further improved this chance to 53% for those ventilated since 1990. In a second article appeared in 2007 (27), the authors reported an additional improvement to 30 years when spinal surgery was combined with nocturnal ventilation. It remains controversial by which way mechanical ventilation should be performed.

In fact, the school of Bach (30) is in favour of a protocol including non-invasive ventilation (NIV), mechanically assisted cough and oximetry, obviating tracheotomy. Conversely, the school of Rideau demonstrates that mini-tracheotomy is able to stabilize the vital capacity in DMD patients, avoiding criticisms during intercurrent respiratory infections and reducing the needs of hospitalization (20-22).

Our data confirm those published by other groups on nocturnal ventilation, and show that – despite this disorder has not a causative therapy – it cannot be considered an incurable disease. The best management of the foremost respiratory complications can in fact improve the life expectancy of these patients, approximately doubling the years of life, as observed in our and in other groups of long experience (24-30).

Compared with the study of Eagle et al., our data show an increased age of death for patients having cardiomyopathy. The fact that our group paid its main attention always to cardiac problems probably explains such a behaviour. Of course we are aware of the fact that the target for future genetic therapies must be the heart, because cardiomyopathy remains the major cause of death, shortening life expectancy in these patients significantly (24, 47-49).

Research is in progress to clarify whether genetic factors (dystrophin-gene related or independent) are able to modify the clinical evolution of the disease (49, and personal data), and then the duration of life of DMD patients. Furthermore, these data underline that Duchenne Dystrophy is not exclusively a child pathology, but has become an adult disease, needing interventions from the health authorities in favour of the patients and their families, especially in the phase of transition between infancy and adult age.

Acknowledgements

The work was in part supported by Telethon Italy (Projects GUP10002, GUP11001, GUP11002 and GTB07001H to LP).

References

- 1.Emery AEH, Muntoni F. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery AEH. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases � a world survey. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90039-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monaco AP, Bertelson CJ, Colletti-Feener C, et al. Localization and cloning of Xp21 deletion breakpoints involved in muscular dystrophy. Hum Genet. 1987;75:221–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00281063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigro G, Comi LI, Limongelli FM, et al. Prospective study of Xlinked progressive muscular dystrophy in Campania. Muscle Nerve. 1983;6:253–262. doi: 10.1002/mus.880060403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nigro G, Comi LI, Politano L, et al. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Cardiol. 1990;26:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90082-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigro G, Comi LI, Politano L, et al. Cardiomyopathies associated with muscular dystrophies. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 1239–1256. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyde SA, Steffensen VF, Floytup I, et al. Longitudinal data analysis: an application to construction of a natural history profile of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11:165–165. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig M, Beggs AH, Moyer M, et al. The molecular basis for Duchenne versus Becker muscular dystrophy: correlation of severity with type of deletion. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;45:498–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malhotra SB, Hart KA, Klamut HJ, et al. Frame-shift deletions in patients with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Science. 1988;242:755–759. doi: 10.1126/science.3055295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntoni F, Gobbi P, Sewry C, et al. Deletions in the 5' region of dystrophin and resulting phenotypes. J Med Genet. 1994;31:843–847. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.11.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prior TW, Bartolo C, Pearl DK, et al. Spectrum of small mutations in the dystrophin coding region. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:22–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prior TW, Bartolo C, Papp AC, et al. Dystrophin expression in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient with a frame-shift deletion. Neurology. 1997;48:486–488. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.2.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muntoni F, Torelli S, Ferlini A, et al. Dystrophin and mutations: one gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:731–740. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooke MH, Fenichel GM, Griggs RC, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: patterns of clinical progression and effects of supportive therapy. Neurology. 1989;39:475–481. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilgoff I, Prentice W, Baydur A. Patient and family participation in the management of respiratory failure in DMD. Chest. 1989;95:519–524. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach JR. Ventilator use by Muscular Dystrophy Association patients. Arch Phys Rehabil. 1992;73:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasuma F, Sakai M, Matsuoka Y. Effects of noninvasive ventilation on survival in patients with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Chest. 1996;109:590–590. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonds AK, Muntoni F, Heather S, Fielding S, et al. Impact of nasal ventilation on survival in hypercapnic Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Thorax. 1998;53:949–952. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.11.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rideau Y, Politano L. Research against incurability. Treatment of lethal neuromuscular diseases focused on DMD. Acta Myol. 2004;23:163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rideau Y, Politano L, Fiorentino G, et al. Struggle for life in lethal muscular diseases: ultimate achievements. Acta Myol. 2010;29:133–133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rideau YM. Requiem. Acta Myol. 2012;31:48–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forst J, Forst R. Surgical treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients in Germany: the present situation. Acta Myol. 2012;31:21–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eagle M, Baudouin SV, Chandler C, et al. Survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: improvements in life expectancy since 1967 and the impact of home nocturnal ventilation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:926–929. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yasuma F, Konagaya M, Sakai M, et al. A new lease on life for patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Japan. Am J Med. 2004;117:363–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toussaint M, Steens M, Wasteels G, et al. Diurnal ventilation via mouthpiece: survival in end-stage Duchenne patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:549–555. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00004906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eagle M, Bourke J, Bullock R, et al. Managing Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the additive effect of spinal surgery and home nocturnal ventilation in improving survival. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manzur AY, Kinali M, Muntoni F. Update on the management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:986–990. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.118141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler M, Clarenbach CF, Bahler C, et al. Disability and survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:320–325. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.141721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bach JR, Martinez D. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: continuous noninvasive ventilatory support prolongs survival. Respir Care. 2011;56:744–750. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzone ES, Messina S, Vasco G, et al. Reliability of the North Star Ambulatory Assessment in a multicentric setting. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:458–461. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.06.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angelini C, Peterle E. Old and new therapeutic developments in steroid treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol. 2012;31:9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazzone E, Martinelli D, Berardinelli A, et al. North Star Ambulatory Assessment, 6-minute walk test and timed items in ambulant boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzone E, Vasco G, Sormani MP, et al. Functional changes in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a 12-month longitudinal cohort study. Neurology. 2011;77:250–25. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biggar WD, Politano L, Harris VA, et al. Deflazacort in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a comparison of two different protocols. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talim B, Malaguti C, Gnudi S, et al. Vertebral compression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy following deflazacort. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:294–295. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigro G, Comi LI, Politano L, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy of muscular dystrophy: a multifaceted approach to management. Semin Neurol. 1995;15:90–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nigro G, Politano L, Passamano L, et al. Cardiac treatment in neuro- muscular diseases. Acta Myol. 2006;25:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Politano L, Palladino A, Nigro G, et al. Usefulness of heart rate variability as a predictor of sudden cardiac death in muscular dystrophies. Acta Myol. 2008;27:114–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Politano L, Nigro G. Treatment of dystrophinopathic cardiomyopathy: review of the literature and personal results. Acta Myol. 2012;31:24–30. and references cited therein. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nigro V, Nigro G, Esposito MG, et al. Novel small mutations along the DMD/BMD gene associated with different phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1907–1908. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nigro V, Politano L, Nigro G, et al. Detection of a nonsense mutation in the dystrophin gene by multiple SSCP. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:517–520. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.7.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nigro G, Politano L, Nigro V, et al. Mutation of dystrophin gene and cardiomyopathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1994;4:371–379. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trimarco A, Torella A, Piluso G, et al. Log-PCR: a new tool for immediate and cost-effective diagnosis of up to 85% of dystrophin gene mutations. Clin Chem. 2008;54:973–981. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torella A, Trimarco A, Vecchio Blanco F, et al. One hundred twenty-one dystrophin point mutations detected from stored DNA samples by combinatorial denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:65–73. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vitiello C, Faraso S, Sorrentino NC, et al. Disease rescue and increased lifespan in a model of cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy by combined AAV treatments. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5051–e5051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lancioni A, Rotundo IL, Kobayashi YM, et al. Combined deficiency of alpha and epsilon sarcoglycan disrupts the cardiac dystrophin complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4644–4654. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rotundo IL, Faraso S, Leonibus E, et al. Worsening of cardiomyopathy using deflazacort in an animal model rescued by gene therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24729–e24729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bello L, Piva L, Barp A, et al. Importance of SPP1 genotype as a covariate in clinical trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2012;79:159–162. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f04ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]