Abstract

Carbohydrate metabolism of barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves induced to accumulate sucrose (Suc) and fructans was investigated at the single-cell level using single-cell sampling and analysis. Cooling of the root and shoot apical meristem of barley plants led to the accumulation of Suc and fructan in leaf tissue. Suc and fructan accumulated in both mesophyll and parenchymatous bundle-sheath (PBS) cells because of the reduced export of sugars from leaves under cooling and to increased photosynthesis under high photon fluence rates. The general trends of Suc and fructan accumulation were similar for mesophyll and PBS cells. The fructan-to-Suc ratio was higher for PBS cells than for mesophyll cells, suggesting that the threshold Suc concentration needed for the initiation of fructan synthesis was lower for PBS cells. Epidermal cells contained very low concentrations of sugar throughout the cooling experiment. The difference in Suc concentration between control and treated plants was much less if compared at the single-cell level rather than the whole-tissue level, suggesting that the vascular tissue contains a significant proportion of total leaf Suc. We discuss the importance of analyzing complex tissues at the resolution of individual cells to assign molecular mechanisms to phenomena observed at the whole-plant level.

The major product of photosynthesis in temperate grass leaves is Suc, which is stored, converted into fructan (the main storage carbohydrate in the vegetative parts of cool-season grasses [Pollock and Cairns, 1991]), or transported through the phloem to other parts of the plant. Fructan synthesis in the leaves of temperate grasses is related to high Suc concentrations in the tissue (Housley and Pollock, 1985; Cairns and Pollock, 1988); however, the control of the competing processes of Suc export and fructan synthesis is not yet clear. The enzymology of fructan synthesis in grasses is also not completely understood (Pollock and Cairns, 1991; Cairns, 1993, 1995).

Synthesis of fructan oligosaccharides in vitro requires both high Suc and high fructosyltransferase concentrations (Cairns 1992, 1995). This implies that the synthesis of fructan in vivo occurs in a cell compartment with high local concentrations of both enzyme and substrate. The vacuole is considered to be the site of fructan biosynthesis (Pollock and Chatterton, 1988), but it is not clear whether the vacuoles of all cell types accumulate fructan equally. Therefore, knowledge of the tissue localization of fructan synthesis and accumulation is necessary to fully understand primary carbohydrate metabolism in leaves. The SiCSA technique (Tomos et al., 1994) has demonstrated that when barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves accumulate sugars they are not uniformly accumulated in all cell types (Fricke et al., 1994; Koroleva et al., 1997). The epidermis contains very low concentrations of sugars and takes no part in carbohydrate storage (Fricke et al., 1994; Koroleva et al., 1997).

A limitation of the SiCSA technique is that it is impossible to determine the proportion of sap from the vacuolar and cytosolic compartments within any sample. The cytosol in mesophyll cells of wheat leaves occupies only 7.2% of cell volume compared with 38.9% for vacuoles (Altus and Canny, 1985). Cytosol occupies 6.7% of total cell volume in barley leaves (Winter et al., 1992). By contrast, the vacuole occupies 99% of the whole cell volume in epidermal cells (Winter et al., 1992). The SiCSA data presented in this study are therefore likely to represent vacuolar sugars to a greater extent than those of the cytosol.

Cells of both the mesophyll and PBS in source leaves of barley accumulate Suc (Koroleva et al., 1997) and are likely to synthesize fructan. Although the mesophyll cells are the major site of Suc synthesis, PBS cells are also capable of photosynthesis, since they contain PSII activity and Rubisco protein (Williams et al., 1989; O.A. Koroleva, unpublished data). The lateral cells of the PBS (S-type cells) may also play an important role in the transport of assimilate to the phloem (Williams et al., 1989).

In this study we sought to determine whether individual epidermal, mesophyll, and PBS cells have different quantitative and qualitative patterns of carbohydrate accumulation in barley leaves when carbohydrate accumulation in the leaf was increased either by reducing export of Suc from the leaf or by increasing photosynthetic rate. Cooling of sinks (roots and shoot apical meristem) to 10°C reduced Suc export from leaves and resulted in accumulation of total carbohydrate and in the induction of fructan synthesis in leaves (Smouter and Simpson, 1991; Plum and Farrar, 1996; Koroleva et al., 1997). The carbohydrate content of source leaves can also be increased by a higher rate of photosynthesis without restricting the export of sugars; therefore, we grew plants for 2 d under high photon fluence rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Plants

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv Klaxon) plants were grown hydroponically in controlled-environment cabinets (Sanyo Gallenkamp, Loughborough, Leicester, UK) at 20°C, a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle, a photon fluence rate of 500 μmol photons m−2 s−1, and 0.035% CO2. The CO2 concentration was maintained by pumping air from 15 m above the ground through the chamber, with four air changes per hour. Seeds were soaked overnight and germinated for 4 d on moist paper. Fourteen seedlings were then transferred to a trough containing one-half-strength Long-Ashton nutrient solution (Hewitt, 1966). Solutions were changed twice a week. The third leaf was fully expanded at about d 14 after transfer. All samples were taken from the middle parts of the third leaves 1 to 5 d after full expansion of the leaf blade.

Cooling Experiments

A low temperature was used to induce the accumulation of fructan (Smouter and Simpson, 1991; Koroleva et al., 1997). The plant roots and the lower 3 cm of the shoot (including the shoot apex) were submerged in nutrient solution at 10°C. The rest of the plant was kept at 20°C. Cooling started on d 1 after the third leaf had fully expanded. Cooling continued for 4 d, and then the solution was warmed to 20°C for the rest of the experiment. Parallel sets of control plants were sampled at the same age as cooled plants.

High Photon Fluence Rate

At full expansion of the third leaf, plants were transferred for 2 d to a chamber with photon fluence rate of 1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The photoperiod, temperature, and CO2 concentration were unchanged.

Measurement of Carbohydrates in Leaf Tissue

Tissue samples were taken from the middle part of leaf lamina, killed in boiling 90% ethanol, and extracted in 90% ethanol at 60°C (Koroleva et al., 1997). Ethanol-soluble sugars were analyzed by HPLC (Cairns and Pollock, 1988). The ethanol extracts were combined, evaporated, and redissolved in water. This fraction was deionized using Dowex 50 (H+) and Dowex 1 (CO32−) columns, concentrated, filtered through a 0.45-μm polysulfene membrane, and analyzed (Aminex HPX 87C column, Bio-Rad) at 85°C, with water as the solvent. The individual fractions were detected with a refractive index detector (model RID-6A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and analyzed with integration software (Valuchrom, Bio-Rad). The fractions were quantified using external standards of similar retention times.

Extraction of Sap from Individual Cells

Sap was extracted from individual epidermal, mesophyll, and PBS cells of barley leaves using a microcapillary. The tip was inserted through a stomatal pore to reach mesophyll and PBS cells. Details of the procedure were given by Koroleva et al. (1997).

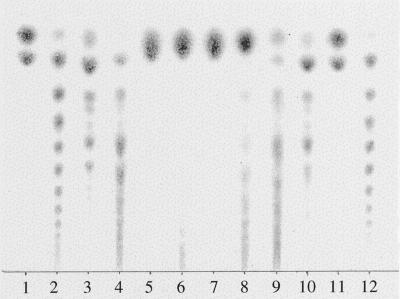

Hydrolysis of Fructans

Conventional acid hydrolysis cannot be used to hydrolyze fructans in single-cell samples because of their small volumes (20–100 pL). We used enzymatic hydrolysis of fructan polymers to Fru for subsequent analysis. Commercial yeast β-fructosidase (invertase) hydrolyzes the three common fructan trisaccharides and also larger oligofructans (Cairns, 1993; Simpson and Bonnett, 1993), whereas Suc phosphorylase will hydrolyze only Suc. We used TLC (Cairns and Pollock, 1988) to assess the invertase activity on fructans extracted from barley leaves. Both Suc and fructan oligosaccharides up to DP 8 from barley leaves (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4) were hydrolyzed completely to hexoses by yeast invertase at pH 4.6 within 1 h (Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6). At pH 7.5 invertase completely hydrolyzed the ethanol-soluble fraction (Fig. 1, lane 7) but not the water-soluble fraction (Fig. 1, lane 8). Suc phosphorylase hydrolyzed more than 50% of Suc during the same 1-h period (Fig. 1, lane 9). The ethanol-soluble fraction (Fig. 1, lane 3) was stable at pH 4.6 (Fig. 1, lane 10).

Figure 1.

Specificity of invertase and Suc phosphorylase activity. TLC plate with lanes containing barley fructans from 80% ethanol-soluble (lane 3) and water-soluble (lane 4) fractions and products of their hydrolysis by yeast invertase (Sigma) at pH 4.6 (lanes 5 and 6, respectively) and at pH 7.5 (lanes 7 and 8, respectively). Suc phosphorylase hydrolyzed Suc from the same water-soluble fraction (lane 9). Oligofructans from the ethanol-soluble fraction were stable in the absence of enzymes at pH 4.6 (lane 10). Suc and Fru (lanes 1 and 11, respectively) and oligoinulins from Helianthus tuberosus (lanes 2 and 12) were used as markers.

The amount of fructan oligosaccharides present in samples was determined as the difference between the amount of hexose produced by the two enzymes (invertase and Suc phosphorylase). The carbohydrate-to-enzyme concentration ratios used for TLC assay were much higher than for single-cell assays, in which complete hydrolysis was always ensured.

Enzymatic Microassay of Carbohydrate Concentrations

Concentrations of various carbohydrates in the sap from single cells were measured using a microfluorometric assay. This assay involves enzymatic dehydrogenation of Glc-6-P derived sequentially from Glc, Fru, Suc, and fructans, with a corresponding reduction of NADP to NADPH. A microscope photometer (MPV Compact 2 Fluorovert, Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) fitted with filter block A and software (Leitz) was used to measure the fluorescence of 4- to 5-nL droplets of a reaction mixture placed on a microscope slide inside a 4-mm-deep aluminum ring under 3 mm of water-saturated paraffin oil. The reaction mixture contained 68 mm imidazole buffer, pH 7.5, 5.6 mm MgCl2, 5.6 mm ATP, 0.1% BSA, 23.8 mm NADP, and 1.2 mm KH2PO4. Three identical subsets of droplets were placed on the slide. The standards and samples (approximately 10 pL) were added with a constriction pipette in the same sequence for all three subsets. Then, 100 pL of Suc phosphorylase (10 units/mL; Sigma) was added to all droplets in subset 2, and 100 pL of β-fructosidase (invertase; 1330 units/mL; Boehringer Mannheim) was added to all droplets in subset 3.

Excess invertase was used, since the enzyme must operate at nonoptimal pH. The initial fluorescence was recorded for all droplets, and Glc phosphorylation was started in all subsets by adding approximately 100 pL of a hexokinase/Glc-6-P dehydrogenase (Boehringer Mannheim) mixture (85/43 units/mL). After 10 to 15 min the reaction was complete (the fluorescence readings increased and then became stable), with the change in NADPH fluorescence being proportional to the amount of Glc in the droplet. The second step of the assay was started by adding 100 pL of phosphoglucose isomerase (Boehringer Mannheim; 175 units/mL). The additional change in NADPH fluorescence after 20 to 30 min indicated the amount of Fru. Measurements of subset 1 gave values for Glc and Fru concentrations present initially in the samples and standards, subset 2 gave the initial amounts of Glc and Fru plus Fru derived from Suc by Suc phosphorylase (the second molecule produced in this reaction, Glc-1-P, is not a substrate for further reactions), and subset 3 was used to estimate total hexose content in the samples and standards after complete hydrolysis of both Suc and fructans. This method provides the total amount of fructan but no information about the DP. Therefore, all measurements of fructan from single cells are expressed as hexose units.

RESULTS

Carbohydrates from Whole-Leaf Tissue

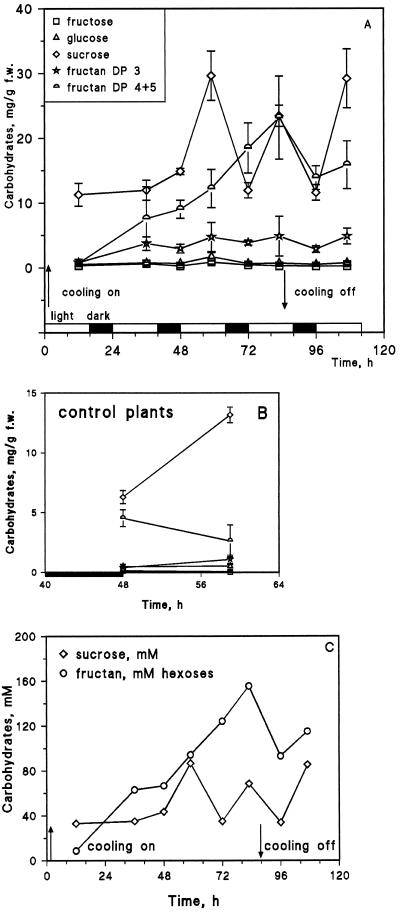

Cooling of sinks increased the ethanol-soluble fraction (which contains most of the carbohydrate) of total carbohydrate of the whole-tissue extracts (Fig. 2), mainly because of increased Suc and fructan concentrations (DP 4 + 5). For example, the Suc concentration was much higher at the end of the third photoperiod (60 h) in the leaf tissue of cooled plants, i.e. approximately 30 mg g−1 fresh weight (Fig. 2A) compared with 13 mg g−1 fresh weight in control plants (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Time course of the content of carbohydrates analyzed by HPLC in tissue samples from the third leaves of barley plants with their roots and shoot apical meristem cooled (A) or uncooled (B; controls). Each point is an average ± sd of three plants. C, Suc and total hexose units from fructan shown on a molar basis to allow comparison with single-cell fructan measurements, in which the DP was unknown. f.w., Fresh weight.

Total carbohydrate accumulation would be somewhat higher than the above values (Koroleva et al., 1997). Hexoses (Glc and Fru) remained at very low concentrations. Suc concentration followed a diurnal pattern in both cooled (Fig. 2A) and control (Fig. 2B) plants. Only part of one cycle is illustrated for the control plants. At the end of the third photoperiod (60 h), the concentrations in control plants were similar compared with the plants at the beginning of the experiment.

The concentration of fructan trisaccharide fluctuated only slightly and remained quite low, which is typical behavior for an intermediate product. The concentration of fructan with a DP 4 + 5 increased steadily during cooling but decreased abruptly immediately after the plants were returned to control conditions (Fig. 2A). To allow comparison of HPLC and SiCSA results, Figure 2C presents an estimate of the molar concentration for Suc and hexose derived from fructan from Figure 2A. For this estimation it was assumed that 1 kg of tissue was equivalent to 1 L of solution.

Carbohydrates from Single Cells

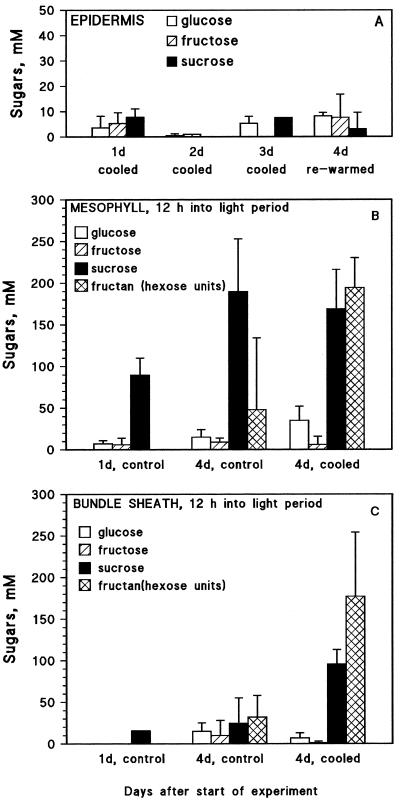

Epidermal cells contain negligible concentrations of sugars and do not accumulate additional carbohydrate when sinks were cooled (Fig. 3A) or after exposure to a high photon fluence rate (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of Glc, Fru, Suc, and fructan (as hexose units) in individual epidermal (A), mesophyll (B), and PBS (C) cells from plants with roots and shoot apical meristem cooled to 10°C and in leaves of control barley plants. Treated plants were cooled for 3 (A) and 4 d (B and C). Control plants were not cooled. Each bar is an average ± sd for three plants; two or three samples of each cell type were analyzed from each plant.

In both mesophyll and PBS cells of control plants, Suc and fructan concentrations increased with leaf age between d 1 (1 d after full expansion of the leaf blade) and d 4 (Fig. 3, B and C). In plants cooled between d 1 and 4, fructan accumulation was 4 to 6 times higher in mesophyll and PBS cells than in control plants. However, the mesophyll Suc concentration was not different for cooled and control plants (Fig. 3B). In PBS cells of the cooled plants the average concentration of Suc after 84 h of cooling was 3 times higher than in the control plants at the same time (Fig. 3C). High light also stimulated fructan synthesis (Fig. 4). In any single experiment (e.g. Fig. 3 or 4), the fructan-to-Suc ratio (in millimolar) was always higher in PBS cells than in mesophyll cells.

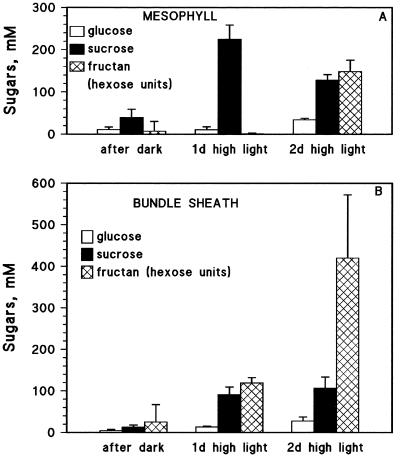

Figure 4.

Concentrations of Glc, Suc, and fructan (as hexose units) in individual mesophyll (A) and PBS cells (B) in barley plants grown at 500 μmol photons m−2 s−1 before transfer to high-light conditions (1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1) and 1 and 2 d after. Each bar is an average ± sd for three plants.

Transferring plants to high light for 2 d had an effect similar to that of cooling. Fructan synthesis was induced, but the total amount of sugars that accumulated was much higher in PBS cells than in mesophyll cells (because of the higher fructan concentration; Fig. 4). The apparent threshold Suc concentration for initiation of fructan synthesis was approximately 100 mm for PBS cells. In mesophyll cells a fixed threshold was less apparent as Suc increased to more than 200 mm at the end of d 1 and then declined to 100 mm by the end of d 2, possibly due to fructan synthesis.

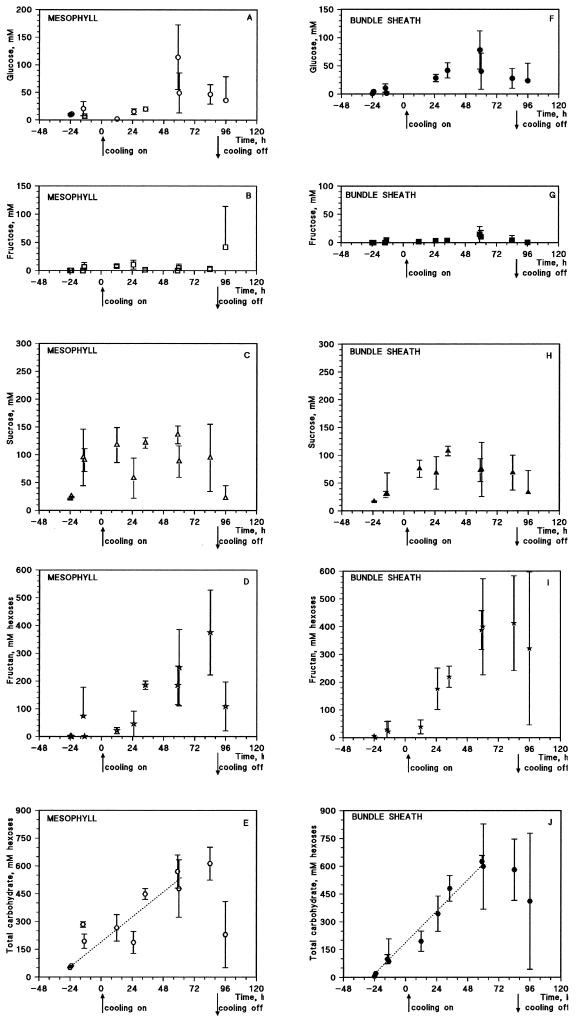

Data from more than 10 experiments were pooled (Fig. 5) to show the trends for each sugar during the 88 h of cooling and subsequent rewarming during a 5-d experiment. Free Glc and Fru concentrations were usually less than 20 mm in both mesophyll and PBS cells for cooled and control plants (Fig. 5, A, B, F, and G), although Glc peaked by 60 h.

Figure 5.

Time courses of different carbohydrate concentrations during cooling experiments in mesophyll cells (A-E) and PBS cells (F-J) of barley plants. Each point is an average ± sd for three to 10 plants combined from 11 experiments. The line was fitted by hand to show the general trend.

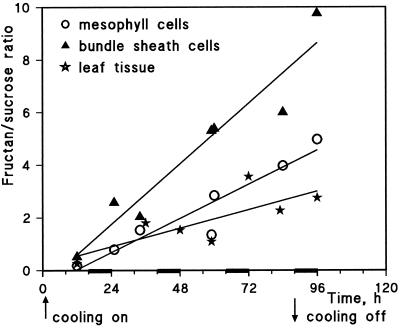

Fructan and total carbohydrate concentration were broadly similar for mesophyll and PBS cells in the cooling experiment, although fructan accumulation may have started earlier in PBS cells (Fig. 5, D, E, I, and J). The fructan-to-Suc ratio was much higher for PBS cells than for mesophyll cells, and they were both higher than the ratio calculated from HPLC data for whole-leaf tissue (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Change of the fructan-to-Suc ratio expressed in millimolar during the cooling experiment for mesophyll and PBS cells and for whole-leaf tissue. Data from Figures 2 and 5 were used for the calculation of these values.

DISCUSSION

SiCSA showed that mesophyll and PBS cells both accumulate Suc and fructans to high concentrations, especially under conditions of reduced export or increased photosynthetic rate. It is interesting that the epidermis does not act as a buffer for leaf Suc accumulation.

High light and sink cooling resulted in quantitatively similar responses, suggesting that the secondary effects of root cooling, such as root-to-shoot signaling or a change in the root hydraulic conductivity, do not affect the accumulation of sugars induced by low sink activity.

The SiCSA technique as described here cannot distinguish between vacuolar and cytoplasmic compartments. If we assume that the ratio of vacuolar sap and cytosol in single-cell samples is the same as for intact cells, the samples represent more of the vacuole (which occupies 38.9% to 73% of mesophyll and 99% of epidermal cell volume) than that of the cytosol (6.7% to 7.2% for mesophyll), and the chloroplasts occupy 17% to 19% of the cell volume in the mesophyll (Altus and Canny, 1985; Winter et al., 1993).

Because the Suc concentration in the mesophyll was nearly the same for plants at the end of the light period irrespective of the treatment (control, reduced leaf export, or increased photosynthetic rate), there may be control of the upper level of Suc accumulation. One explanation is that there is a definite threshold in Suc concentration (150–200 mm) for the induction of fructan synthesis (Pollock, 1986).

The existence of a threshold concentration of Suc at which fructan synthesis is induced is consistent with findings from other studies. Illuminated, excised leaves of Lolium temulentum L. provided an estimate of 15 mg g−1 fresh weight (Cairns and Pollock, 1988), excised illuminated barley leaves had 18 to 20 mg g−1 fresh weight (Tomos et al., 1992; Simmen et al., 1993), and excised barley leaves with Suc applied exogenously in the dark suggested a value of 17 mg g−1 fresh weight (Wagner et al., 1986). These values all fall within a range of 40 to 60 mm if expressed on a whole-tissue basis. Subsequent fructan synthesis appears to require this range of Suc concentration in leaf tissue (Wagner et al., 1986; Cairns and Pollock, 1988; Cairns, 1992).

Suc concentrations similar to those presented here were found in isolated mesophyll protoplasts from illuminated, excised leaves of L. temulentum (Cairns et al., 1989). These were 110 mm (assuming that all Suc is vacuolar) or 100 mm (assuming equal concentrations in the cytoplasm and vacuole). In vitro Km values for enzymes of fructan synthesis in grasses suggest that such high Suc concentrations are needed. The total SST activity increased linearly with substrate concentration over the range of 100 to 700 mm (Cairns et al., 1989; Cairns, 1995). The activity of 1-SST from excised barley leaves displayed a Km of 200 mm, whereas 6-SST activity increased linearly up to at least 600 mm Suc (Simmen et al., 1993). In vitro Suc concentrations of less than 80 mm led to synthesis of only the trisaccharide isokestose.

The role and anatomical position of PBS cells were quite different from those of mesophyll cells. The function of PBS cells may be to accumulate Suc coming apoplastically or symplastically from mesophyll cells and to regulate passage of this Suc to the interior of the vascular bundle for export into the phloem. When export of Suc from the PBS was reduced (Fig. 3) or its synthesis was increased (Fig. 4), PBS cells accumulated up to approximately 100 mm Suc. The concentration of Suc was usually lower in the PBS than in the mesophyll, possibly because PBS cells start fructan synthesis earlier (Figs. 3, 4, and 5, D and I). In PBS cells (Fig. 3C) the threshold Suc concentration for the initiation of fructan synthesis seems to be lower. Both the rate of Suc and fructan accumulation and the fructan-to-Suc ratio are different for mesophyll and PBS cells from the same leaf (Figs. 3, 4, 5, C, D, H, and I, and 6).

The fructan-to-Suc ratio (Fig. 6) was much higher for PBS cells; therefore, the rate of Suc export from these cells to the veins may have been higher than that from mesophyll cells to PBS. The equilibrium between Suc export and its use for fructan synthesis may also be different to maintain a step gradient in Suc concentration to allow continued diffusive flow toward the PBS. The passage of Suc can proceed through the plasmodesmatal continuity (Farrar et al., 1992). The general behavior of PBS and mesophyll cells in terms of Suc accumulation and fructan synthesis are, however, broadly similar.

The concentration of Glc was always at least 10 times less than that of Suc in whole-leaf extracts (Fig. 2). However, it was much higher in some cell-sap samples, with a peak Glc concentration of more than 50% of the Suc concentration appearing at d 3 in both mesophyll and PBS cells (Fig. 5, A and F). This Glc peak is also seen in Figure 2 but is not as highly expressed. The increase in Glc concentration following induction of fructan synthesis has also been seen in excised primary barley leaves (Wagner et al., 1986; Simmen et al., 1993) at values up to 55 mm averaged for the leaf tissue. This Glc concentration was not due to invertase activity, because there was no accumulation of Fru at the same time. Furthermore, the activity of acid invertase in the mesophyll and PBS cell sap was low (Koroleva et al., 1997). It may be that a high Suc concentration, together with activity of specific fructosyltransferases that use the fructosyl moiety from the Suc molecules to build up fructan polymers, results in the accumulation of Glc residues. This accumulation of Glc could also be responsible for the decrease in the CO2 assimilation rate (Krapp et al., 1991) that is observed in the leaves of barley plants during cooling (Plum and Farrar, 1996; Koroleva et al., 1997).

Sugars control the expression of many plant genes and therefore many metabolic and developmental processes (Koch, 1996). If sugar repression of photosynthesis represents a general mechanism for the regulation of the photosynthetic rate in response to changes in demand (Jang and Sheen, 1994), Suc is not likely to be the major agent since its concentration in mesophyll cell sap is generally within the range of that in control plants. Jang and Sheen (1994) showed in maize that the expression of photosynthetic genes was suppressed by lower concentrations of Glc than of Suc, suggesting that the ability of Suc to cause repression is dependent on its hydrolysis. Glc has been shown to act as a metabolic regulator independently of stress-related stimuli (Ehness et al., 1997).

Comparing sugar concentrations measured at the tissue level and in single mesophyll and PBS cells gives a unique opportunity to compare carbohydrate accumulation in a whole leaf with processes happening in individual cells. Comparison of the fructan-to-Suc ratio of single cells with that for whole tissue suggests that a substantial part of the leaf Suc was located in cells that were not sampled, most likely the vascular tissue. Indeed, autoradiography of barley leaves fed 14CO2 shows strong labeling of the veins (J. Farrar, unpublished data).

It was not possible earlier to conclude from tissue-level measurements the actual concentration of Suc in leaf cells. For Suc content measured in whole tissue it is especially important to know what proportion of it is located in the phloem, where the concentration is extremely high. This was estimated by Winter et al. (1992) to be 1030 mm at 9 h into the light period and 930 mm after 5 h in the dark, whereas the Suc concentration in the cytosolic compartment of the leaf (9 h into the photoperiod) was calculated as 150 mm. The total volume of sieve tube and companion cells is unknown, and it is not possible to compare the amounts of Suc located in the leaf cells and the phloem elements.

We recalculated the expected amounts of carbohydrate in various leaf compartments from our single-cell data using cellular volumes estimated by Winter et al. (1993) for primary barley leaves: 27% in the epidermis, 42% in the mesophyll, and 6% in the veins. Similar values were obtained for seven annual and perennial grass species (Garnier and Laurent, 1994). Because epidermal cells contain a negligible concentration of Suc, the concentration of about 100 mm in mesophyll cells would correspond to 42 to 62 mm Suc in whole-leaf tissue. The measured tissue concentrations are higher, i.e up to 80 mm (Fig. 2C). The difference in concentration of at least 20 mm is consistent with high concentrations in the phloem, the volume of which is less than the 6% found in the veins (Winter et al., 1993; Garnier and Laurent, 1994). However, calculating the concentrations for a volume of 6% gives values of approximately 330 mm, which is one-third of the estimated value of the phloem Suc concentration (1 m; Winter et al., 1992). If phloem elements occupy one-third of the vascular tissue, they would contain approximately 1 m Suc. These calculations are supported by the fact that the fructan concentration, which presumably is excluded from bundles, was lower at the tissue level (Fig. 2C) than in mesophyll and PBS cells.

It is clear that metabolism is compartmented between subcellular organelles, and much is known of the subcellular organization of photosynthesis. Until now, however, it has proved very difficult to assess the intercellular compartmentation within the same subcellular compartment. This study shows that different cells within a complex tissue such as a leaf behave very differently. Applying the SiCSA technique will make it considerably easier to assign molecular mechanisms to phenomena that until now have been accessible only at the whole-leaf level.

Abbreviations:

- DP

degree of polymerization

- PBS

parenchymatous bundle sheath

- SiCSA

single-cell sampling and analysis

- SST

Suc-to-Suc-fructosyltransferase

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council (research grant no. 5/PO 2288).

LITERATURE CITED

- Altus DP, Canny MJ. Loading of assimilates in wheat leaves. II. The path from chloroplast to vein. Plant Cell Environ. 1985;8:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ. Fructan biosynthesis in excised leaves of Lolium temulentum L. V. Enzymatic de novo synthesis of large fructans from sucrose. New Phytol. 1992;122:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1992.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ. Evidence for the de novo synthesis of fructan by enzymes from higher plants: a reappraisal of the SST/FFT model. New Phytol. 1993;123:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ. Effects of enzyme concentration on oligofructan synthesis from sucrose. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ, Pollock CJ. Fructan biosynthesis in excised leaves of Lolium temulentum L. I. Chromatographic characterisation of oligofructans and their labelling patterns following 14CO2 feeding. New Phytol. 1988;109:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ, Winters A, Pollock CJ. Fructan biosynthesis in excised leaves of Lolium temulentum L. III. A comparison of the in vitro properties of fructosyl transferase activities with the characteristics of in vivo fructan accumulation. New Phytol. 1989;112:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ehness R, Ecker M, Godt DE, Roitsch T. Glucose and stress independently regulate source and sink metabolism and defense mechanisms via signal transduction pathways involving protein phosphorylation. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1825–1841. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.10.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar J, van der Shoot C, Drent P, van Bel A. Symplastic transport of Lucifer Yellow in mature leaf blades of barley: potential mesophyll-to-sieve-tube transfer. New Phytol. 1992;120:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke W, Leigh RA, Tomos AD. Concentrations of inorganic and organic solutes in extracts from individual epidermal, mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells of barley leaves. Planta. 1994;192:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier E, Laurent G. Leaf anatomy, specific mass and water content in congeneric annual and perennial grass species. New Phytol. 1994;128:725–736. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt EJ (1966) Sand and water culture methods used in the study of plant nutrition. In Technical Communication no. 22. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham Royal, UK

- Housley TL, Pollock CJ. Photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in detached leaves of Lolium temulentum L. New Phytol. 1985;99:499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Jang JC, Sheen J. Sugar sensing in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1665–1679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KE. Carbohydrate-modulated gene expression in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:509–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva OA, Farrar JF, Tomos AD, Pollock CJ. Solute patterns in individual mesophyll, PBS and epidermal cells of barley leaves induced to accumulate carbohydrate. New Phytol. 1997;136:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp A, Quick WP, Stitt M. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, other photosynthetic enzymes and chlorophyll decrease when glucose is supplied to mature spinach leaves via the transpiration stream. Planta. 1991;186:58–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00201498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum SA, Farrar JF. Carbon partitioning in barley following manipulation of source and sink. Aspects Appl Biol. 1996;45:177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ. Fructans and the metabolism of sucrose in higher plants. New Phytol. 1986;104:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1986.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ, Cairns AJ. Fructan metabolism in grasses and cereals. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ, Chatterton NJ. Fructans. In: Preiss J, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants, A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol 14: Carbohydrates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 109–140. [Google Scholar]

- Simmen U, Obenland D, Boller T, Wiemken A. Fructan synthesis in excised barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:459–468. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson RJ, Bonnett GD. Fructan exohydrolase from grasses. New Phytol. 1993;123:453–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smouter H, Simpson R. Fructan metabolism in leaves of Lolium rigidum Gaudin. I. Synthesis of fructan. New Phytol. 1991;119:509–516. [Google Scholar]

- Tomos AD, Hinde P, Richardson P, Pritchard J, Fricke W. Microsampling and measurement of solutes in single cells. In: Harris N, Oparka KJ, editors. Plant Cell Biology—A Practical Approach. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1994. pp. 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Tomos AD, Leigh RA, Palta JA, Williams JHH (1992) Sucrose and cell water relations. In CJ Pollock, JF Farrar, AJ Gordon, eds, Carbon Partitioning within and between Organisms. BIOS, Oxford, UK, pp 71–89

- Wagner W, Wiemken A, Matile P. Regulation of fructan metabolism in leaves of barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv Gerbel) Plant Physiol. 1986;81:444–447. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.2.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, Farrar JF, Pollock CJ. Cell specialization within the parenchymatous bundle sheath of barley. Plant Cell Environ. 1989;12:909–918. [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Lohaus G, Heldt HW. Phloem transport of amino acids in relation to their cytosolic levels in barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:996–1004. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.3.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Robinson DG, Heldt HW. Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in barley leaves. Planta. 1993;191:180–190. [Google Scholar]