Abstract

To understand cell fate specification and maintenance during development, it is essential to visualize both lineage markers and cell behaviors in real time using endogenous markers to report cell fate. We have generated a reporter line in which eGFP is fused to the endogenous locus of Cdx2, a transcription factor essential for trophectoderm specification, allowing us to visualize cell fate decisions in the pre-implantation mouse embryo. We utilized two-photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM) to visualize expression of the endogenous Cdx2 fusion protein, and show that Cdx2 undergoes phases of up-regulation. Additionally, we show that as late as the 32-cell stage, outer trophectoderm cells may change their fates by migrating inward and losing Cdx2 expression. Furthermore, the tools and techniques we report allow for dual-colored imaging which will greatly facilitate the study of pre-implantation development.

Keywords: Cdx2, Pre-implantation, Live-Imaging, Mouse embryo, Two-photon microscopy

Introduction

One of the major challenges in understanding mammalian embryo development is the difficulty in deciphering how the expression of transcription factors required for lineage specification is coupled with cell morphogenesis and behavior. To overcome this challenge it is critical to develop markers and imaging techniques that allow for the tracking of endogenous transcription factor expression and cellular behavior simultaneously for an extended time without compromising embryo viability. The pre-implantation mouse embryo, which contains a small number of cells undergoing cell fate specification, provides an excellent live model system to study the coupling between lineage specification and cell behaviors. Considerable work has been done to establish how cells in the mouse embryo differentiate into the earliest lineages, yet most of these studies have centered on the use of fixed immunofluorescence analyses or spatiotemporally restricted live imaging. Existing live lineage analyses in the mouse embryo rely on transgenic insertions such as histones fused to fluorescent proteins, injection of mRNAs encoding fluorescently-tagged proteins, dyes, or fluorescently labeled markers that have the potential to disrupt, influence, or misrepresent cell fates.

Recent studies have provided insights into how dynamic behaviors of transcription factors can influence cell fates in the pre-implantation mouse embryo (Plachta et al., 2011), which demonstrate the power of using live imaging to understand developmental processes. A major limitation of imaging pre-implantation development live is the lack of fluorescently labeled lineage-specific transcription factors expressed from their endogenous promoters. Consequently, it has been difficult to study how the rate of gene expression and turnover correlate with cell position and morphogenesis. Additionally, the sensitivity of the mouse embryo to light exposure and environmental conditions, coupled with the thickness and density of the embryo, further challenge the use of conventional confocal microscopy to visualize the entirety of pre-implantation development. We report the use of tools and techniques that overcome these difficulties, and have uncovered important insights into pre-implantation development.

Results

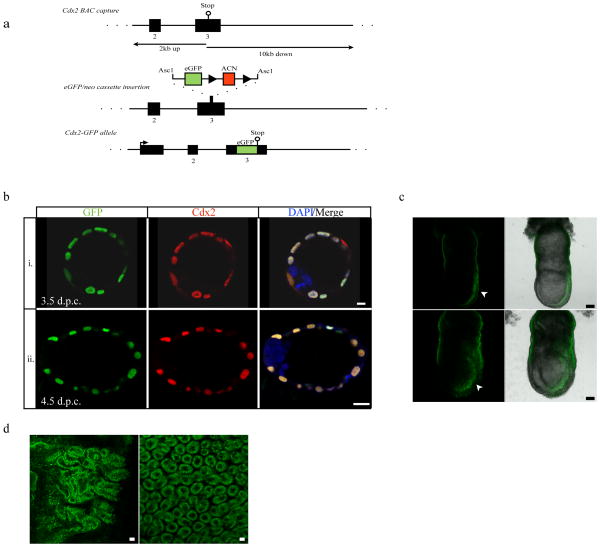

The transcription factor Cdx2 is a critical component to the development of outer, trophectoderm-fated cells in the pre-implantation embryo, and is commonly used to report cell fate status in both mouse embryos and differentiating embryonic stem (ES) cells (Niwa et al., 2005; Ralston and Rossant, 2008; Strumpf et al., 2005). In addition, Cdx2 is used as a marker in intestinal epithelial development and colon cancer (Moskaluk et al., 2003; Silberg et al., 2000). Cdx2-null embryos cannot maintain the blastocoel cavity and fail to implant around 4.5 days post coitus (d.p.c.) (Strumpf et al., 2005). Using a modified version of the recombineering protocol established by the Capecchi lab (Wu et al., 2008) we introduced enhanced GFP (eGFP) in-frame to the C-terminus of Cdx2 by homologous recombination, which results in the expression of a Cdx2-GFP fusion protein from the endogenous Cdx2 promoter (Fig. 1a). Mice with this targeted knock-in are viable, fertile, and possess a normal appearance and life span even when homozygous for the Cdx2-GFP fusion allele. The GFP signal in these embryos co-localizes with Cdx2 as shown by anti-Cdx2 antibody and is visible in both pre- and peri-implantation embryos (Fig. 1b). Additionally, Cdx2-GFP can be visualized live in the posterior (primitive streak) of 7.0–7.5 d.p.c. embryos and in the epithelia of the small intestine in adult (5 week old) mice (Fig. 1c, and 1d) following normal Cdx2 expression and distribution (Deschamps and van Nes, 2005; Grainger et al., 2010; Strumpf et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Cdx2-GFP fusion allele expressed from the endogenous promoter. (a) Recombineering strategy to create a targeted Cdx2-GFP fusion protein by knocking-in GFP using targeted Asc1 restriction sites to introduce the reporter/selection cassette. Mice either heterozygous or homozygous for the Cdx2-GFP fusion allele are viable and fertile. (b) GFP expression in the Cdx2-GFP heterozygous embryos co-localizes with the endogenous Cdx2 as determined by immunofluorescence. GFP survives fixation and is visible at pre- and peri-implantation stages. i) 3.5 dpc. ii) 4.5 dpc. Scale bars, 10 μm (top), 20 μm (bottom). (c) Cdx2-GFP expression in two (top and bottom) live 7.0–7.5 d.p.c. heterozygous embryos. GFP expression can be found in the posterior end in the primitive streak (arrow heads). Scale bars, 70 μm (top), 100 μm (bottom). (d) Cdx2-GFP expression in live small intestine from heterozygous 5-week old female mice. GFP expression is found throughout the epithelial layer (left) and villi (right). Scale bars, 20 μm.

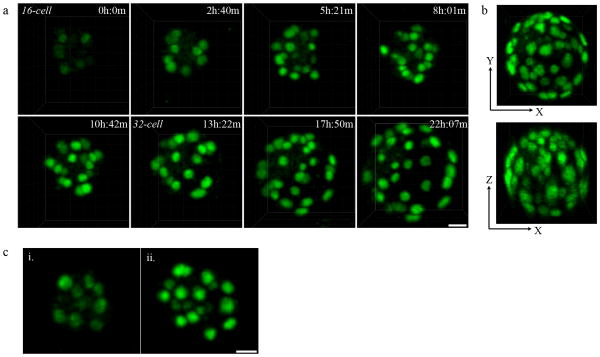

In live pre-implantation embryos the Cdx2-GFP signal is bright enough to be detected under a fluorescence dissection microscope. In order to simultaneously track Cdx2-GFP expression and the behavior of Cdx2-GFP positive cells throughout the embryo during the entire pre-implantation stage of development, we utilized two-photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM). We have previously described the use of TPLSM as an excellent technique providing high spatiotemporal resolution to image transgenic Histone 2B-GFP (H2B-GFP) mouse embryos over the entire course of pre-implantation development with negligible delay or toxicity to embryos (McDole et al., 2011). Similar imaging conditions were applied to study Cdx2-GFP embryos from the late 8-cell to 64-cell stages. Contrary to studies using fixed immunohistochemistry to visualize Cdx2 expression, we found that Cdx2-GFP was not detectable until the 16-cell stage (Fig. 2a, see Supplementary Information, Movie S1), consistent with the low initial Cdx2 expression reported previously (Strumpf et al., 2005). Using two-photon microscopy, we are able to achieve full-thickness resolution even at the 64-cell stage under laser intensities that produce no or negligible delays in embryo development (Fig. 2b). Although the axial resolution of two-photon microscopy is reduced compared to that of conventional single-photon confocal microscopy (Fig. 2b), we are still able to clearly resolve individual Cdx2-GFP positive nuclei. Under these conditions, we observed that the initial Cdx2-GFP expression was gradually up-regulated during the 16-cell stage until the 16-cell to 32-cell division when outer-cells experienced a sharp increase in Cdx2 expression immediately after dividing (Fig. 2a and b). Notably, we found that both maternal (Cdx2-GFP mother and CD1 WT father) and paternal (CD1 WT mother and Cdx2-GFP father) alleles begin to express during the 16-cell stage (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Imaging of endogenous Cdx2 expression live. (a) Cdx2-GFP expression from the 16-cell stage to the 64-cell stage. Still frames taken from a time-lapse movie of a single embryo using TPLSM show Cdx2-GFP expression beginning at the early to mid 16-cell stage, and is gradually up-regulated over time. Embryos are viable and develop with minimal or no delay under these conditions. Scale bar, 20 μm. (b) Two-photon microscopy provides full-thickness resolution of an expanded 64-cell stage blastocyst in both XY (top) and XZ (bottom) planes. (c) Increase of Cdx2-GFP expression following 16-cell to 32-cell division. Cdx2-GFP is noticeably brighter immediately after dividing from the 16-cell stage (i.) to the 32-cell stage (ii.). Scale bar, 20 μm.

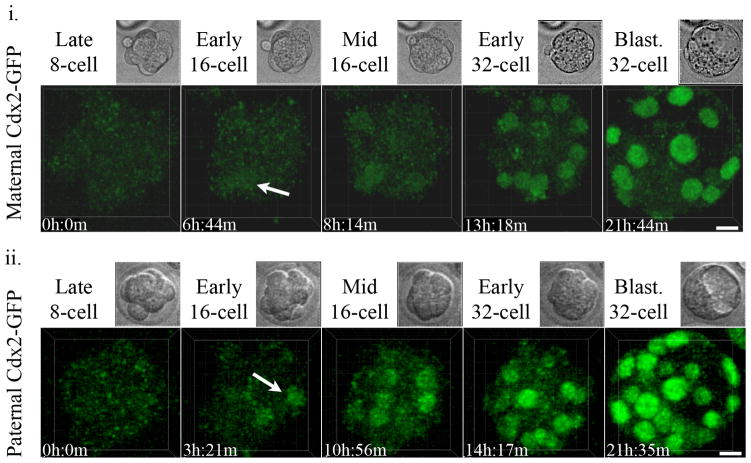

Figure 3.

Expression of Cdx2-GFP from maternal (Cdx2-GFP mother and CD1 WT father) (i.) or paternal (CD1 WT mother and Cdx2-GFP father) (ii.) alleles begins at the 16-cell stage (arrows indicate start of expression). Scale bar, 15 μm. Movies were obtained on two different days using different imaging settings. Maternal Cdx2-GFP was imaged using a conventional scanner, Paternal Cdx2-GFP was imaged under similar conditions using a resonant scanner.

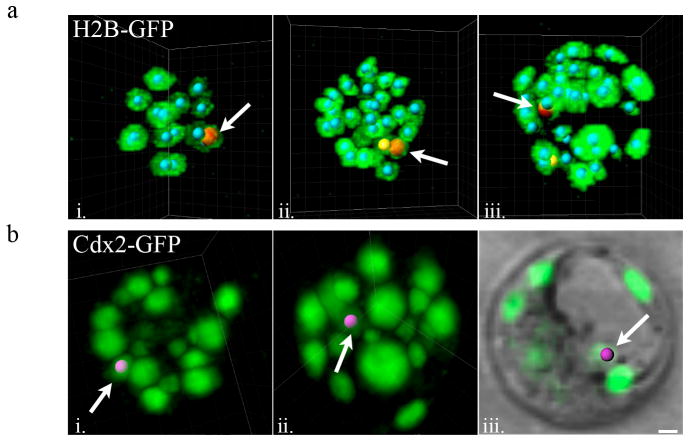

Our ability to visualize all Cdx2-expressing cells in the embryo allowed us to follow the behavior of these cells. Using the high temporal resolution provided by TPLSM imaging in combination with H2B-GFP labeled nuclei, we previously uncovered a population of outer cells termed “transient-outer cells” at the 32-cell stage that display an unexpected behavior. These cells are observed on the outside of the embryo similar to other trophectoderm cells throughout the 16-cell and 32-cell morula stages. However, just prior to or during cavitation these cells suddenly migrate inward and occupy a new position in the inner cell mass (ICM) facing the blastocoel cavity in the putative primitive endoderm (Fig. 4a). Given their positions on the outer surface of the embryo prior to this migration, we wondered whether these cells were trophectoderm cells that underwent a cell fate change. Using our Cdx2-GFP imaging model, we found that these transient-outer cells indeed expressed Cdx2 at the same intensities as other outer trophectoderm cells, and continued to do so during inward migration (Fig. 4b). However, while these cells still expressed Cdx2 immediately after migrating inward, their GFP intensity gradually decreased and was typically undetectable by the 32 to 64 cell-stages (data not shown). We believe that these internalized transient outer cells may explain the presence of Cdx2 positive cells found in the ICM of blastocyst-stage embryos in studies using immunofluorescence microscopy (Nishioka et al., 2009). These cells demonstrate that cell fate can change significantly later than what had been proposed by previous studies of pre-implantation development (Pedersen et al., 1986; Suwinska et al., 2008). Moreover, the repositioning and cell fate change occurs during interphase, as opposed to during asymmetric cell division where daughter cells assume different cell fates, implying an active cell-sorting mechanism (McDole et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2010). It remains to be seen whether these cells are assuming inner cell fates, contributing to the primitive endoderm, or if they are instead undergoing apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Transient-outer cells expressing Cdx2-GFP migrate inward during cavitation. (a) Still frames taken from time-lapse movies using transgenic H2B-GFP expressing embryos. Nucleus marked with red “spot” and denoted by arrow marks a transient outer-cell that moves inward during cavitation. Nucleus marked with yellow “spot” is the outer-cell sibling of the red-labeled transient outer-cell after the 16-cell to 32-cell division (i. 16-cell stage, ii. 32-cell stage, iii. 32-cell blastocyst stage) (b) Cdx2 positive outer-cell at the 32 cell stage (i., nucleus labeled with pink “spot”) moves inward during cavitation (ii.) and shortly thereafter in the cavitated blastocyst resides in the ICM facing the blastocoel cavity (iii.). Scale bar, 10 μm.

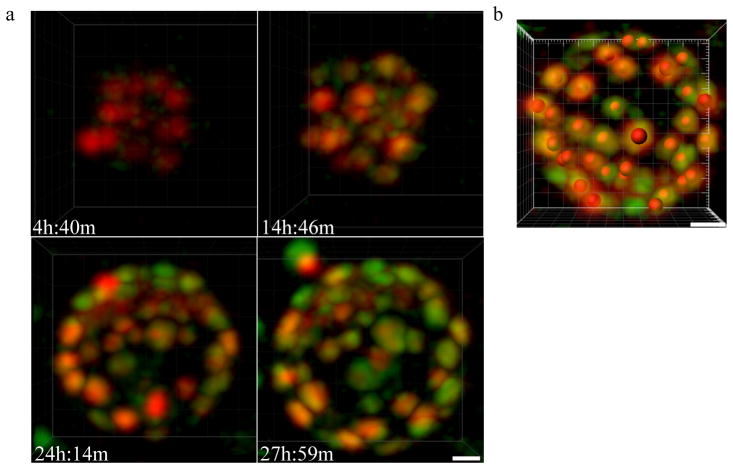

The use of multiple fluorescent markers will be instrumental in determining both the eventual cell fates of the transient-outer cells and allowing for the tracking of multiple cell fate markers and cell positions for the entire embryo. Using a transgenic Histone-2B-mCherry expressing mouse line combined with our Cdx2-GFP fusion line, we demonstrate the ability of TPLSM to visualize two fluorescent markers simultaneously while still maintaining good embryo viability and spatiotemporal resolution (Fig. 5a), enabling tracking and labeling of individual cell nuclei and their Cdx2-GFP expression over time (Fig. 5b). Dual-color labeling and tracking with high spatiotemporal resolution are essential steps forward in visualizing and correlating cell position and behavior with lineage assignment.

Figure 5.

Dual-colored imaging of a mouse embryo using TPLSM. (a) Still images from a time-lapse movie of an embryo expressing both H2B-mCherry and Cdx2-GFP. Embryos were imaged using 740 nm (mCherry) and 890 nm (GFP) excitation wavelengths and a resonant scanner. Scale bar, 15 μm. Gaussian filtering was performed in IMARIS to eliminate noise created by use of the resonant scanner. (b) A single frame from a movie of H2B-mCherry and Cdx2-GFP expressing embryos at the 64-cell stage is shown. Red spots mark nuclear positions representing H2B-mCherry positive nuclei. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

The continuing development of non-linear imaging methods such as TPLSM will further advance the ability of these systems to obtain valuable and detailed information about developmental dynamics and cell fate establishment in the embryo. Advances in genetic engineering and imaging systems have made this a fertile time to advance our understanding of cell fate establishment using the simple and easily obtainable mouse embryo as a model. Here we demonstrate the ability of these systems to visualize real-time endogenous markers using Cdx2-GFP.

Interestingly, while immunohistochemical analyses using Cdx2 antibody show Cdx2 expression as early as the 8-cell stage, using our endogenous Cdx2-GFP reporter we were unable to visualize any live Cdx2-GFP signal until the 16-cell stage, even at the highest laser intensities. This discrepancy may be due to the sensitivity of antibody staining that allows for the detection of minuscule amounts of protein, or it may reflect the stability of Cdx2 protein at this stage of development. If Cdx2 protein undergoes rapid turnover at the 8-cell stage, antibody staining may amplify the small amount of protein but the transient GFP signal may be difficult to visualize live. The availability of a Cdx2-GFP reporter mouse line will permit the study of Cdx2 protein stability during pre-implantation development, and further demonstrates the need for live, endogenous reporters to illuminate authentic cell fate decisions and behavior.

Using our Cdx2-GFP reporter line, we were also able to observe the inward migration of Cdx2-GFP positive outer cells. This behavior helps to explain the presence of Cdx2-positive cells in the putative primitive endoderm. Further studies using dual-color tracking will be essential in discovering the final fates of these unusual and intriguing cells. With this system we have gained insights into inconsistencies that were unresolvable using either immunofluorescence analysis or by live imaging using single-photon confocal microscopy. These new insights and techniques should stimulate further development and refinement of canonical models of embryo development.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and generation of mouse lines

Plasmids used to create the Cdx2-GFP fusion line were generously provided by M. Capecchi, and the following protocol was used for the vast majority of the targeting strategy (Wu et al., 2008). The Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) containing Cdx2 was obtained from BACPAC Resources at the Children’s Hospital and Research Center at Oakland (Oakland, CA), RP23-7616. Primers were synthesized to capture a fragment 2kb upstream (short arm) and 10kb downstream (long arm) of the Cdx2 stop codon with ~50bp homology to each arm of the BAC clone and a shorter sequence homologous to the insertion site of the pStart-K vector. 2kb BAC Primer: GAA AGT GAC CAG AGT CCC CAG GAA TAT CAA TAT CCA CAT TTT CAG ACT TGC GAC TGA ATT GGT TCC TTT AAA GC 10kb BAC Primer: CCA CCA CGC CTG GCT GTA ACT TAT TTT CTA AAT CTG GTA TTG GAA TGA TGT GCC GCA CTC GAG ATA TCT AGA CCC A. Capture and proper insertion of each arm was confirmed by sequencing. Due to repetitive sequences and complex secondary structure of the Cdx2 arm near the stop codon, insertion of the chloramphenicol resistance gene (CAT) cassette was performed by overlap PCR amplifying a 700bp region upstream of the stop codon using Roche Expand Long Template PCR (11681834001, RAS) along with a reverse primer containing the addition of a single adenine to shift the reading frame in frame with that of the eGFP cassette in conjunction with two overlapping primers to capture the Asc1-CAT-Asc1 fragment from the pKD3 vector. The resulting fragment containing the Asc1-CAT-Asc1 insertion was transformed into Red-competent DH5α-pKD46 cells along with the pStartK-Cdx2 BAC plasmid. Colonies were screened by restriction digest and sequencing to select for proper insertion of the recombined fragment as well as CAT insertion. Insertion of the neo cassette and Gateway recombineering into the pWS-TK6 vector was then performed as outlined in the Capecchi protocol. pWS-TK6.Cdx2GFP was then electroporated into F1 C57Bl/6 X 129Sv hybrid ES cells (generously provided by Dr. Chengyu Liu) and selected using ganciclovir (for TK selection) and G418 (for neo selection). Colonies were screened by using Expand Long Template PCR to amplify fragments containing sequences outside of the 2kb short-arm and within the GFP insertion cassette to select for proper targeting. Positive colonies were additionally confirmed by sequencing. ES cells were karyotyped to ensure correct chromosome number, and injected into CD1 wild-type blastocysts that were then implanted into pseudo-pregnant CD1 females. Chimeras were screened for germline transmission using the following genotyping primers: Cdx2 Fw: ATG GTT CCG TTC CCT GGT TC and GFP R: GCG GAC TTG AAG AAG TCG TGC TGC TT, yielding a ~750bp band and Cdx2 Fw and Cdx2 Ex3 R: AGG CTT GTT TGG CTC GTT ACA C, which yields a ~1,400bp band for the WT allele, and ~2,100bp for the GFP-fusion allele after self-excision of the neo cassette.

Pups resulting from germline transmission were viable, and mice carrying both heterozygous and homozygous copies of the Cdx2-GFP fusion allele appear normal, viable and fertile. Expression of the Cdx2-GFP allele was confirmed by embryo dissection and co-staining with anti-Cdx2 antibody. Cdx2-GFP mice used for this study were maintained in a mixed genetic background from CD1, 129Sv, and C57Bl/6J strains. This line will be made available to the scientific community and it is our intention to deposit it in a public repository for ease of access. Histone 2B-mCherry mice were generated as described previously (Vong et al., 2010).

Embryo culture and intestine dissection

Cdx2-GFP males or Cdx2-GFP females (for maternal allele expression) were crossed with natural, hormone-primed, or super-ovulated CD-1 wild-type females or males (for maternal allele expression) and checked for the presence of a vaginal plug the next day (noted as 0.5 d.p.c.). Embryos were harvested at a 2-cell or 8-cell stage by oviduct flushing using M-2 medium (MR-015-D, Millipore) and cultured in droplets of KSOM-AA medium (MR-106-D, Millipore) covered with a layer of mineral oil (M8410, Sigma) at 37°C and 5% CO2 until imaging. Embryos were imaged on WPI 35 mm glass cover-slip dishes (FD35-100, World Precision Instruments). 7.0–7.5 d.p.c. embryos were collected from CD1 females naturally mated with Cdx2-GFP males and imaged in PBS on glass cover-slip dishes using TPLSM at 890 nm excitation. Small intestine samples were collected from 5 week old Cdx2-GFP heterozygous females, flushed with PBS and cut lengthwise before flattening between a cover-glass and slide and imaging on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope with 488 nm excitation.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were harvested as described above, and fixed at the appropriate stages in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10–15 min, and then permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20–30 min before blocking for 1 hr in 10% FBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Embryos were then incubated in primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, and the next morning washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1–2 hours. Cdx2 primary antibody was used at a 1:200 dilution, (mouse anti-Cdx2, Biogenex, Cdx2-88). Secondary antibody Alexa Flour 568 goat anti-mouse (1:1,000) and DAPI (at 1μg/mL) were used.

Imaging and reconstruction

Embryos were imaged on an inverted Leica SP5 II MP system with a Chameleon Ti:Sapphire laser (Coherent Inc.) enclosed by a Ludin Life Imaging chamber incubation system maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Z-stacks were collected every 7–10 minutes with 2 μm sections (~55 total) at 890 nm for GFP and 740 nm for mCherry, using either a conventional or resonant scanner if the embryos were single-color (Cdx2-GFP) or dual-color (Cdx2-GFP and H2B-mCherry), respectively. Movies were reconstructed using IMARIS software (Bitplane, AG). Gaussian filtering was used to eliminate noise created by the use of the resonant scanner in the cases where it was used. Spots were created to mark nuclear positions by using the Spot Identification Function.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information, Movie S1. Time-lapse movie of an embryo expressing endogenous starting at the 16-cell stage using two-photon laser scanning microscopy at 890 nm excitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chen-Ming Fan and Ona Martin for their valuable knowledge and help in the creation of the Cdx2-GFP reporter line. We would also like to thank Eugenia Dikovskaia for her help in blastocyst injection and chimera generation and Shiying Jin for advice and help preparing intestinal samples. This work was funded by from the NIAAA, grant R21 AA020060-02.

References

- Deschamps J, van Nes J. Developmental regulation of the Hox genes during axial morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:2931–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.01897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger S, Savory JG, Lohnes D. Cdx2 regulates patterning of the intestinal epithelium. Developmental biology. 2010;339:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDole K, Xiong Y, Iglesias PA, Zheng Y. Lineage mapping the pre-implantation mouse embryo by two-photon microscopy, new insights into the segregation of cell fates. Developmental biology. 2011;355:239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Teo RT, Li H, Robson P, Glover DM, Zernicka-Goetz M. Origin and formation of the first two distinct cell types of the inner cell mass in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskaluk CA, Zhang H, Powell SM, Cerilli LA, Hampton GM, Frierson HF., Jr Cdx2 protein expression in normal and malignant human tissues: an immunohistochemical survey using tissue microarrays. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2003;16:913–919. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086073.92773.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka N, Inoue K, Adachi K, Kiyonari H, Ota M, Ralston A, Yabuta N, Hirahara S, Stephenson RO, Ogonuki N, Makita R, Kurihara H, Morin-Kensicki EM, Nojima H, Rossant J, Nakao K, Niwa H, Sasaki H. The Hippo signaling pathway components Lats and Yap pattern Tead4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Dev Cell. 2009;16:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Strumpf D, Takahashi K, Yagi R, Rossant J. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell. 2005;123:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen RA, Wu K, Balakier H. Origin of the inner cell mass in mouse embryos: cell lineage analysis by microinjection. Developmental biology. 1986;117:581–595. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plachta N, Bollenbach T, Pease S, Fraser SE, Pantazis P. Oct4 kinetics predict cell lineage patterning in the early mammalian embryo. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:117–123. doi: 10.1038/ncb2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston A, Rossant J. Cdx2 acts downstream of cell polarization to cell-autonomously promote trophectoderm fate in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;313:614–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg DG, Swain GP, Suh ER, Traber PG. Cdx1 and cdx2 expression during intestinal development. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:961–971. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumpf D, Mao CA, Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Chawengsaksophak K, Beck F, Rossant J. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development. 2005;132:2093–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.01801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwinska A, Czolowska R, Ozdzenski W, Tarkowski AK. Blastomeres of the mouse embryo lose totipotency after the fifth cleavage division: expression of Cdx2 and Oct4 and developmental potential of inner and outer blastomeres of 16- and 32-cell embryos. Dev Biol. 2008;322:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vong QP, Liu Z, Yoo JG, Chen R, Xie W, Sharov AA, Fan CM, Liu C, Ko MS, Zheng Y. A role for borg5 during trophectoderm differentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/stem.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Ying G, Wu Q, Capecchi MR. A protocol for constructing gene targeting vectors: generating knockout mice for the cadherin family and beyond. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1056–1076. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information, Movie S1. Time-lapse movie of an embryo expressing endogenous starting at the 16-cell stage using two-photon laser scanning microscopy at 890 nm excitation.