Abstract

Genetic association studies have become standard approaches to characterize the genetic and epigenetic variability associated with cancer development, including predispositions and mutations. However, the bewildering genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity inherent in cancer both magnifies the conceptual and methodological problems associated with these approaches and renders the translation of available genetic information into a knowledge that is both biologically sound and clinically relevant difficult. Here, we elaborate on the underlying causes of this complexity, illustrate why it represents a challenge for genetic association studies, and briefly discuss how it can be reconciled with the ultimate goal of identifying targetable disease pathways and successfully treating individual patients.

Keywords: cancer heterogeneity, genetic predispositions, somatic mutations, genetic association studies

The heterogeneity of cancer

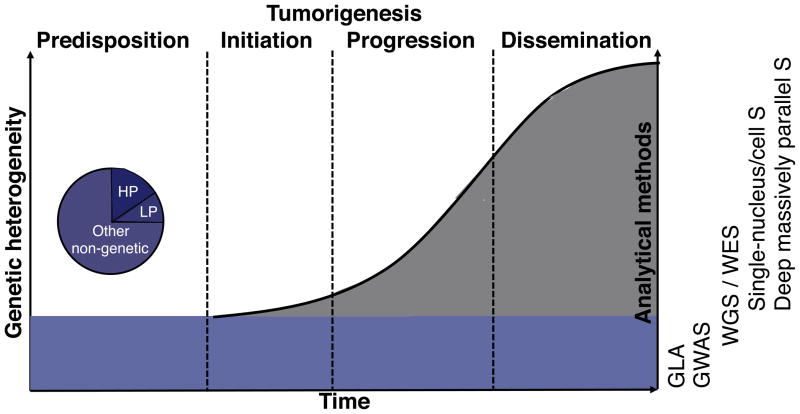

Cancer results from an accumulation of mutations and epigenetic modifications in somatic cells. Together with inherited genetic variations predisposing to the disease, these alterations contribute to the conversion of normal human cells into malignant ones [1] during the multistep process of tumorigenesis (Figure 1). The exceptional genetic complexity inherent to cancer is primarily attributable to variation across cancers, tumors, and patients in the type, number, and the sequence and rate of accumulation of somatically acquired alterations [2]. However, additional layers of complexity originate from inherited variations, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions, and from interactions between tumor cells and their micro-environment [3]. This genetic complexity results in highly heterogeneous phenotypes and a diversity of pathologies, clinical symptoms, resistance profiles, therapeutic responses, and prognoses.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of heterogeneity levels within a cancer patient. Predispositions (blue) remain identical throughout tumorigenesis but can differently affect any step of it. De novo mutations (grey) accumulate from initiation to dissemination at a rate that varies over time and depends on the background of predispositions and on environmental effects. Predispositions can be of high or low penetrance (hp or lp) and can target other functional units such as regulatory elements or mRNA. Lp and hp predispositions are typically characterized with GWAS and Genetic Linkage Analysis (GLA), respectively, whereas somatic mutations are studied using WGS and WES, single-nucleus and single-cell sequencing (Single-nucleus/cell S), and deep massively-parallel sequencing (Deep massively-parallel S) data. The latter methods can also be used to characterize predispositions.

The development of new technologies for the rapid, cost-effective, and detailed sequencing of individual tissues and tumors provides us with unprecedented amounts of data. Yet our ability to leverage this data to advance our understanding of biological pathways and disease etiology may remain limited if the methods for analyzing and interpreting those data lag behind the technology. Furthermore, the translation of this data to the clinic is hampered by the near isolation from other scientific fields that could contribute fundamental insights. Here we discuss the origin of genetic complexity in cancer, its characterization, and the challenges that lay ahead in its interpretation and ultimately in the translation of novel knowledge about cancer heterogeneity from bench to bedside. We believe that the current paradigm in cancer research does not fully acknowledge this complexity and that data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation need to be reevaluated in light of this heterogeneity. We do not focus on epigenetic modifications, which, although significant contributors to carcinogenesis [2,4], are beyond the scope of this piece.

Heterogeneity in the variome

Most of the genetic heterogeneity inherent to cancer results from somatic mutations arising in the tumor. However, these mutations do not arise on a blank slate but on a background of inherited germline alterations, the variome, that predispose to cancer. Risk-associated germline alterations take various forms, ranging from single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) to structural variants (e.g., copy neutral or number variation) [5,6], each of which can elicit different cancers even when expressed in the same gene (e.g., different germline TP53 mutations are associated with diverse Li-Fraumeni syndromes [7]). Genetic predispositions can be broadly classified as either high- or low-penetrance (hp or lp) (Box 1) [8]. Hp predispositions are generally rare and occur at low frequencies [6,8] but are often useful pieces of information for estimating individual risk [8]. Lp susceptibilities are common, but the predicted risk associated with each of them is low and their functional significance remains limited and uncertain [9]. Hp predispositions are typically located in well-characterized coding regions of the genome, whereas most lp variants identified to date map to non-coding regions (intergenic and untranscribed regions) [10].

Box 1. High- and low-penetrance predispositions.

Hp predispositions (e.g., mutations in the APC gene in colorectal cancer and in BRAC1/2 genes in breast cancer [6]) show Mendelian inheritance, are associated with early cancer onset, cause most mutation carriers to express the disease phenotype, and strongly predispose carriers to several kinds of cancer [8]. Because of their large detrimental fitness effects, hp variants are rare. Lp predispositions (e.g., polymorphisms in estrogen receptor gene ESR1 in breast cancer or in the apoptosis-inducing gene BIK in prostate cancer [6]) have small effect sizes and low frequencies, and they combine additively or multiplicatively (epistatsis) with other lp or occasionally hp predispositions to increase or modify susceptibility [6]. Hp predispositions are typically identified with linkage and positional cloning followed by DNA resequencing of candidate genes, whereas genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are applied for the latter [6].

The complexity associated with the diversity of types, penetrances, and locations of genetic predispositions is exacerbated by the fact that predispositions can impact both every aspect of cancer, from initiation to the development of resistance (e.g., resistance to anti-EGFR therapies induced by the germline T790M EGFR mutation [11]), and every step of tumorigenesis in a patient-specific manner (e.g., the same germline TP53 mutation can result in tumors of varying severity that develop at different anatomical sites at different times [7]).

Heterogeneity in the mutome

The mutome consists of the somatic mutations that arise from cancer initiation [12,13] to dissemination and metastasis [14], and varies in size as cancer progresses and selection operates. Somatic mutations mirror germline mutations in their penetrance [2,15] and association with different cancer types when they occur in the same gene [2,16] (e.g., translocations and substitutions in the RET proto-oncogene cause papillary thyroid carcinoma and medullary thyroid cancer, respectively) [17]. However, somatic alterations vary in additional ways, leading to complex genetic and phenotypic landscapes [15,18] and high intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity: (i) variation in number: from less than ten in childhood medulloblastomas [19] to tens of thousands in primary lung adenocarcinoma [20]); (ii) variation in accumulation rate: mutations can arise during a “big bang” event [21,22] or accumulate slowly over years or decades [23]; (iii) variation in prevalence: certain mutations occur recurrently in particular cancer types (e.g., FOXL2 mutations are very common in granulosa cell tumors of the ovary [24]), whereas others arise recurrently in a range of cancers, but at different frequencies within each type (e.g., TP53 and PIK3CA both occur in many cancers but are particularly recurrent in breast cancer [25,26]); and finally (iv) variation in sequence.

Somatic alterations affect the interactions of that cell with other cells and its microenvironment, shaping its fitness (i.e., net replication rate) and phenotype (e.g., proliferation, invasion, angiogenic potential). The resulting phenotypic variability among cells serves as substrate for selection through intercellular competition for resources, immunosurveillance, or anticancer treatment, which in turn drives single progenitor cell clones along adaptive landscapes and towards fitness peaks [27,28]. These selective events and ensuing genetic bottlenecks cause substantial reductions in the mutation repertoire, which may not get replenished if mutation rates are lower at later stages of cancer (e.g., in pancreatic cancer [29]). Successful clones typically carry a few driver mutations providing a selective growth advantage and numerous passenger mutations considered neutral [30]. Yet, because fitness effects are context-dependent, the selective value of a given mutation can change as the tumor evolves over time and in response to treatment [3,31]. Such changes in selective value can also affect germline mutations. For example, in hereditary ovarian carcinomas, germline mutations in BRCA1 can become passengers after secondary somatic events, resulting in resistance to platinum chemotherapy [32,33]. Moreover, the coexistence of and interaction between neutral mutations may lead to novel cellular phenotypes [31] and increased evolvability [34], or to increased phenotypic plasticity, thereby adding genetically underpinned variability and triggering unexpected forms of therapeutic resistance. Together with random genetic drift, the Darwinian-like evolutionary process of cancer progression [28] results in mosaics of heterogeneous clones within primary tumors [1,27] and is traditionally assumed to be linear. Yet various cancers (e.g., pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia [35], colon cancer [36], clear cell renal cell carcinoma [37]) appear to follow complex branching models of clonal succession, with particular alterations arising more than once, in no preferential order, or simultaneously in different sub-clones [35,36,38].

Genomic complexity naturally has a phenotypic counterpart [31], which implies variation in the chronology of physiological modifications in cancer cells and in the sequence in which novel biological capabilities (e.g., apoptosis evasion or metastatic capability) are acquired [1,39]. This, in turn, results in phenotypically diverse subpopulations of tumor cells [40], substantial variation in histological appearance [41], and variable disease progression patterns, survival prospects, clinical diagnoses, and therapeutic responses [3,31].

G × G, G × E, and other interactions that contribute to heterogeneity

Interactions occur amongst genes and between genes or cells and their environment [3]. Inherited and somatically acquired alterations can interact with each other (G × G) in an enhancing (synthetic sickness or lethality) or suppressive manner (synthetic viability) [3], the sum of which impacts cancer progression, response to therapy, resistance, and prognosis [3,42]. For a cell to survive newly acquired mutations need to be compatible with pre-existing ones (synthetic viability), and pathways must be buffered against the tendency of new mutations to generate sub-optimal phenotypes (functional buffering) [3]. Accordingly, mutations in the TP53 gene should precede BRCA loss-of-function mutations in breast cancer, as functional P53 induces cell-death or cell-cycle arrest when BRCA is dysfunctional [3].

Gene-Environment (G × E) interactions are important regardless of whether a cancer is primarily genetically or environmentally determined. In the extreme case of genetically-determined familial cancers [43], environmental factors serve to unveil inherited mutations or their pathways, influence the type and acquisition rate of novel mutations likely to arise [15] [44], or alter the epigenome [31]. In patients carrying a mutation in the xeroderma pigmentosum gene for example, exposure to ultraviolet radiation can increase skin cancer risk by a factor of ten thousand before the age of 20 [45]. In colorectal cancer, dietary habits serve to activate oncogenes (e.g., Ras) and inactivate tumor suppressors (e.g., APC) and genes involved in DNA mismatch repair [46]. Conversely, heritable genetic factors also contribute to strongly environmentally-induced malignancies. In bladder cancer, smoking-associated susceptibility increases in the presence of NAT2 polymorphisms, resulting in decreased acetylation of aromatic amines, which is considered a carcinogen detoxifying process [47].

Additional interactions that contribute to the phenotypic heterogeneity of cancer and to the evolutionary history of cellular clones include interactions between individual mutations and the cell of origin in which they arise, which result in divergent phenotypes [3] (e.g., the oncogenic ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene [48]), and between individual tumor cells and the microenvironment in which they grow [3,31].

Genetic association studies for cancer: what are we really gaining from technological improvements?

Despite the availability of efficient methods to access and characterize the heterogeneity of cancer, including SNP-, whole-genome- (WGS), and whole-exome (WES)-sequencing technologies, to date most studies and clinical protocols have treated cancer as a homogeneous entity. What then do these methods achieve? They provide us with massive amounts of detailed data and with catalogues of genetic variants putatively associated with cancer, including predisposing genetic polymorphisms and new genetic variants [49,50]. Yet they provide essentially no key to understand the functional consequences of the loci identified, the pathways they affect, and the interactions that generate cancer, resistance to treatment, relapse, and the multitude of phenotypes observed in cancer patients. New putative associations are reported every day. Yet, gaining a better understanding of the data at hand and applying this understanding to formulate novel hypotheses to guide our search for new etiologically and clinically important variants takes disproportionally long and remains an extraordinary challenge.

Identifying genetic predispositions

WGS and WES data can both be used in genetic association studies to identify predispositions. However, SNP-based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) remain the most common approach. Although useful to obtain a general sense of the genetic architecture of cancer susceptibility, GWAS suffer from serious limitations [51,52]: they are not optimized to detect forms of variation other than SNPs [6]; they are not designed to detect epistasis [38]; they suffer from critical losses in statistical power with each additional test of association [38]; and they perform poorly in the presence of environmental effects [52], multiple risk haplotypes at individual loci [53], numerous loci associated with particular phenotypes [54], low-frequency risk alleles, or small effect size [52,53]. Hence, given the nature of lp susceptibilities in cancer, GWAS are fairly ill suited for their detection. Moreover, as GWAS are a data- rather than a hypothesis-driven discovery process and their success is estimated based on the mere identification of novel genetic associations, a potential disconnect may grow between the raw data and the biological understanding of cancer predisposition required for treatment. However, illustrations exist that data-driven research can be informative and help explain long-standing clinical problems [55], but these may be exceptions rather than general trends.

The substantial limitations inherent to GWAS were acknowledged early on, and a number of guidelines have been implemented to overcome them. In particular, emphasis has been put on applying study designs that account for population stratification, include large sample sizes, apply stringent criteria for the selection of healthy and diseased subjects, and involve replication in independent cohorts [52,56]. Still, it is unrealistic to accrue the 15,500 to 25,100 samples necessary to detect at least five additional susceptibility loci with a probability of 80% within the range of effect sizes seen in current GWASs for breast, colon, and colorectal cancers [54]. This is particularly true if population structure (e.g., ethnicity) or evolutionary history is taken into account. Optimizing study design and sampling strategies is a more realistic approach, as illustrated by the successful identification of an undetected locus associated only with ER-negative and triple-negative tumors in a sample restricted to BRCA1 mutation carriers [57]. This approach is limited however, as the tools available for classifying tumors are insufficient. In breast cancer for instance, hierarchical clustering analysis used for microarray-based class discovery appears subjective [58,59], and single sample predictors used to classify patients into subtypes seem to work well only for basal-like tumors [60]. Alternatives to mRNA-based classifications are progressively being explored and include modeling of gene-expression microarray data [61–63] and classifications based on microRNAs [64] and on epigenetic profiling such as DNA methylation patterns [65].

More recently, new statistical methods have also been developed [66], but their power is often not acceptable, and their performance varies with the underlying assumptions about the relationship between rare variants and complex traits [51]. We suggest that this latter problem ought to be addressed by performing sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the results with respect to various methods and assumptions and by replicating results in different samples.

An alternative to existing solutions, which we think is very promising, is the use of data mining [Box 2]. Data mining methods are designed to handle very large data sets and can efficiently achieve various tasks [67]. For example, GWAS identify candidate SNPs, but these are of limited used in the clinic; by contrast, data mining can predict a patient’s disease status based on a SNP set, which gets us closer to a clinical application.

Box 2. Statistics for genetic association studies and data mining.

In GWAS, the existence of associations between the frequency of common genetic variants and given phenotypes is commonly tested using chi-square tests or logistic regression analysis, and a threshold of statistical significance of p < 5*10−8. Once a subset of SNPs is found to be significant in the GWAS, this limited “discovery set” can be genotyped in a replication set, leading to an even smaller subset of SNPs that can again be genotyped. Alternatively, association studies can be replicated with different samples, and GWAS results can be prioritized based on meta-analyses. Traditional statistical methods are underpowered for GWAS: even highly conservative p-values don’t make up for the huge number of false positives generated by parametric models, and significance testing in GWAS requires permutation test procedures that impose a heavy computational burden. An alternative to traditional statistics is data mining, which is broadly defined as a set of agnostic approaches for identifying patterns in large data sets and overcoming the “curse of dimensionality” associated with vast amounts of data. Rather than fit unique predefined models to entire sets of data, like traditional statistics, data mining approaches first reduce the number of genetic loci using available genomic and biological information and subsequently explore the space of possible models in a computationally feasible manner. Progress in genetic data mining is driven by the recognition that gene-gene interactions are likely to be ubiquitous in human diseases and that their identification represents a major statistical and computational challenge [46,47]. While traditionally applied to the detection of interactions, they can also serve the purpose of detecting linear relationships between genetic predispositions and disease phenotypes. Methods utilized in data mining are gradually being implemented in somatic mutation prediction procedures and are used to explore the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer data set for instance [80].

Identifying somatic mutations

Identifying genetic variants and mutations specific to individual cell lineages relies on WGS and WES, and a number of large-scale projects are involved in cataloging somatic mutations in individual tumors and cancer type (e.g., the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC)). These efforts have detected new risk-associated variants notably at regulatory elements [68–70] and in microRNA (miRNA)-encoding regions [71,72], and they have led to the reconstruction of clonal evolution [73]. More recently, the realization that there is considerable intra-tumor heterogeneity highlighted the need for single-nucleus [21] and single-cell exome [74,75] sequencing to draw the genetic landscapes of tumors in sufficient detail, understand patient-specific patterns of tumor progression and treatment response, and ultimately devise personalized treatments. Accordingly, single-cell sequencing in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and healthy tissues showed that mutations that are recurrent at a population level are not systematically identified in individual patients and tumors [75]. Other recently adopted approaches to characterize intra-tumor heterogeneity include deep massively-parallel sequencing in spatially distinct samples of individual tumors and metastases. Using this approach, it was estimated that more than 60% of all somatic mutations identified in samples of renal carcinomas were not detected in every tumor region and that numerous distinct and spatially separated mutations occur within single tumors [37].

Taking into account spatial patterns in mutational profiles is a significant step towards understanding patient-specific cancer heterogeneity and acquiring the necessary data for personalized diagnosis and treatment planning. Yet, the possibility that mutations vary in their selective value over time [76] highlights the need for longitudinal data. Ultimately, we believe that both spatial and temporal tumor sampling is necessary, a challenge that is not technologically insurmountable but exacerbates the problems associated with analyzing and interpreting large amounts of data.

Future directions

To formulate hypotheses that can guide future genetic association studies and help identify targetable disease pathways, we need to develop new and improve the existing bioinformatics tools for analyzing the available data. The recent development of bioinformatics methods tailored specifically for WGS and WES data [77] is a promising start. Even more importantly, we need to prioritize the functional characterization of the cancer risk loci already identified [9,44]. It is only by moving away from a gene-centered approach through integration of multiple data sources [78] and application of tools borrowed from other domains of science [9,44,79] that we will truly acquire the biological understanding [79] that is necessary and relevant in the clinic. With efficient methods to combine, analyze, and interpret -omics data, searching the gigantic space of cancer-associated variation will become feasible.

Concluding remarks

The future of genetic association studies and of personalized cancer treatment will depend on the analysis of both extant and emerging genomic data and on a dialogue between experts in various biomedical fields. It requires us to prioritize the development of analytical methods and the formulation of biological hypotheses as much as the fine-tuning of sequencing technologies and to build upon the experience acquired with GWAS to best exploit the opportunities offered by massively-parallel sequencing technologies. Acquiring data has become trivial and this by itself is a success. Yet we fear that the growing disconnect between data collection and analysis, not to mention interpretation, might hinder true progress in our understanding of the genetics and the etiology of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants LM010098, LM009012, and AI59694 to JHM, P20 ES018175R01 and RD-83459901 to MRK, and R01CA155004 to ML.

GLOSSARY

- Cell of origin

cancer cell in which a driver mutation initially arises

- Divergent phenotypes

phenomenon occurring when identical driver mutations generate tumors that display distinct histological characteristics or clinical behaviors or arise at different anatomical sites

- Driver mutation

mutation that is causally implicated in oncogenesis; it confers a growth advantage to the cancer cell and is under positive selection in the tissue microenvironment in which the tumor develops

- Epistasis

non-additive interactions between two or more variants at different loci, such that their combined phenotypic effect deviates from the sum of their individual effects

- Evolvability

the capacity of a system to generate adaptive genetic diversity and evolve through natural selection

- Functional buffering (genetic canalization)

ability of complex molecular systems to buffer against the tendency of new alleles to negatively affect cell fitness or viability

- Genetic association study

study aimed at detecting association between one or more genetic polymorphisms and a continuous or discrete trait

- Genetic predisposition

single nucleotide variants (SNVs), structural variants, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) inherited across generations and increasing the susceptibility to express a disease [5–7]

- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

studies aimed at identifying associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and observable traits, including disease phenotypes. GWAS are specifically designed for the detection of common variants

- Linkage analysis

methods of localizing disease genes by genotyping genetic markers in families to identify regions associated with diseases more often than expected by chance

- Mutome

fraction of somatically mutated genes

- Oncogenic ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene

genetic rearrangement of the ETV6 gene identified in various cancers (congenital fibrosarcomas, cellular mesoblastic nephromas, secretory carcinomas of the breast, acute myeloid leukemias), and in tumors from distinct anatomical sites, distinct differentiation lineages, and displaying different clinical behaviors. This genetic aberration illustrates the phenomenon of divergent phenotypes

- Passenger mutation

genetic alteration arising during carcinogenesis that provides no selective advantage to tumor cells. Passenger mutations can become drivers (and vice versa) after secondary somatic events and interact to generate increased evolvability, or increased phenotypic plasticity

- Penetrance

the frequency with which mutation carriers show the phenotype associated with that mutation. If the penetrance of a mutation is high, predisposition is high and many individuals carrying that allele will express the associated phenotype

- Phenotypic plasticity

the ability to change phenotype stochastically or in response to a change in the environment, as opposed to a genetic change

- Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

specific position in a genome where a nucleotide (A, T, C, or G) differs between chromosomes in individuals of the same species

- Somatic mutation

acquired mutation occurring in diploid somatic cells – as opposed to haploid germline cells involved in reproduction – that can be passed on to the progeny of mutated cells during cell division

- Structural variant (SV)

form of larger-sized genetic variation including copy number variants, deletions, insertions, translocations, and other complex genetic rearrangements

- Variome

fraction of germline mutations inherited across generations

- Whole-exome sequencing

selective sequencing of the exons and flanking intronic sections of the human genome to identify novel genes associated with rare and common disorders

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podlaha O, et al. Evolution of the cancer genome. Trends Genet. 2012;28:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashworth A, et al. Genetic interactions in cancer progression and treatment. Cell. 2011;145:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berdasco M, Esteller M. Aberrant epigenetic lanscape in cancer: how cellular identity goes awry. Dev Cell. 2010;19:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shlien A, et al. Excessive genome DNA copy number variation in the Li-Fraumeni cancer predisposition syndrom. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11264–11269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802970105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher O, Houlston RS. Architecture of inherited susceptibility to common cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:353–361. doi: 10.1038/nrc2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malkin D. Predictive genetic testing for childhood cancer: taking the raod less traveled by. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:546–548. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000140650.65591.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank SA. Genetic predisposition to cancer – insights from population genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:764–771. doi: 10.1038/nrg1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman ML, et al. Principles for the post-GWAS functional characterization of cancer risk loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:513–518. doi: 10.1038/ng.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manolio TA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yung CH, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sc. 2008;105:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crespi B, Summers K. Evolutionary biology of cancer. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michor F, et al. Dynamics of cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nrc1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenman C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Futreal PA, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng C, Mulligan LM. Mutation of the RET proto-oncogene in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndromes, related sporadic tumours, and Hirschsprung disease. Hum Mut. 1997;9:97–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:2<97::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjöblom T, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons DW, et al. The Genetic Landscape of the Childhood Cancer Medulloblastoma. Science. 2011;331:435–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1198056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee W, et al. The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature. 2010;465:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature09004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–95. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephens PJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones S, et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4283–4288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah SP, et al. Mutation of FOXL2 in granulosa-cell tumors of the ovary. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:2719–2729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivier M, et al. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karakas B, et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA oncogene in human cancers. Brit J Cancer. 2006;94:455–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank SA. Somatic evolutionary genomics: mutations during development cause highly variable genetic mosaicism with risk of cancer and neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1725–1730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merlo LMF, et al. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nature. 2006;6:924–935. doi: 10.1038/nrc2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yachida S, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–U1126. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stratton MR, et al. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marusyk A, et al. Intra-tumor heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakai W, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008;451:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nature06633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards SL, et al. Resistance to therapy caused by intragenic deletion in BRCA2. Nature. 2008;451:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/nature06548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner A. Neutralism and selectionism: a network-based reconciliation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:965–974. doi: 10.1038/nrg2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson K, et al. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature. 2011;469:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature09650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprouffske K, et al. Accurate reconstruction of the temporal order of mutations in neoplastic progression. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1135–1144. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Notta F, et al. Evolution of human BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2011;469:362–368. doi: 10.1038/nature09733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geyer FC, et al. Molecular analysis reveals a genetic basis for the phenotypic diversity of metaplastic breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 2010;220:562–573. doi: 10.1002/path.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Da Silva L, et al. Tumor heterogeneity in a follicular carcinoma of thyroid: a study by comparative genomic hybridization. Endo Patho. 2011;22:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s12022-011-9154-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan GJ, et al. The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czene K, et al. Environmental and heritable causes of cancer among 9.6 million individuals in the Swedish family-cancer database. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:260–266. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stratton MR. Exploring the genomes of cancer cells: progress and promise. Science. 2011;331:1553–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1204040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradford PT, et al. Cancer and neurologic degeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum: long term follow-up characterises the role of DNA repair. J Med Genet. 2011;48:168–176. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.083022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Jong MM, et al. Low-penetrance genes and their involvement in colorectal cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker and Prev. 2002;11:1332–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsieh FI, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of N-acetyltransferase 1 and 2 and risk of cigarette smoking-related bladder cancer. Brit J Cancer. 1999;81:537–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lannon CL, Sorensen PHB. ETV6-NTRK3: a chimeric protein tyrosine kinase with transformation activity in multiple cell lineages. Sem Cancer Biol. 2005;15:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan XJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:309–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puente XS, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galvan A, et al. Beyond genome-wide association studies: genetic heterogeneity and individual predisposition to cancer. Trends Genet. 2010;26:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark AG, et al. Determinants of the success of whole-genome association testing. Gen Res. 2005;15:1463–1467. doi: 10.1101/gr.4244005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singleton AB, et al. Towards a complete resolution of the genetic architecture of disease. Trends Genet. 2010;26:438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park J, et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide assocation studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat Genet. 2010;42:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prahallad A, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chanock SJ, et al. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antoniou AC, et al. A locus on 19p13 modifies risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers and is associated with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer in the general population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:885–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pusztai L, et al. Molecular classification of breast cancer: limitations and potential. The Oncologist. 2006;11:868–877. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-8-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mackay A, et al. Microarray-based class discovery for molecular classification of breast cancer: analysis of interobserved argreement. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:662–673. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigelt B, et al. Breast cancer molecular profiling with single sample predictors: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:339–349. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Curtis C, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2000 breast tumors reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guedj M, et al. A refined molecular taxonomy of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:1196–1206. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abu-Asab M, et al. Evolutionary medicine: a meaningful connection between omics, disease, and treatment. Prot Clin Appl. 2008;2:122–134. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu J, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fackler MJ, et al. Genome-wide methylation analysis identifies genes specific to breast cancer hormone receptor status and risk of recurrence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ladouceur M, et al. The empirical power of rare variant association methods: results from Sanger sequencing in 1,998 individuals. Plos Genet. 2012:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ziegler A, et al. Biostatistical aspects of genome-wide association studies. Biomet J. 2008;50:8–28. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright JB, et al. Upregulation of c-MYC in cis through a large chromatin loop linked to a cancer risk-associated Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01384-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gaulton KJ, et al. A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat Genet. 2010;42:255–U241. doi: 10.1038/ng.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X, et al. Integrative functional genomics identifies an enhancer looping to the SOX9 gene disrupted by the 17p24.3 prostate cancer risk locus. Gen Res. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.135665.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wojcik SE, et al. Non-coding RNA sequence variations in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia and colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:208–215. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bader AG, et al. The promise of MicroRNA replacement therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7027–7030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ding L, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hou Y, et al. Single-Cell exome sequencing and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell. 2012;148:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu X, et al. Single-Cell exome sequencing reveals single-nucleotide mutation characteristics of a kidney tumor. Cell. 2012;148:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Norquist B, et al. Secondary somatic mutations restoring BRCA1/2 predict chemotherapy resistance in hereditary ovarian carcinomas. J Clinic Oncol. 2011;29:1–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding J, et al. Feature based classifiers for somatic mutation detection in tumour-normal paired sequencing data. Bioinf. 2011;28:167–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cowper-Sal Iari R, et al. Layers of epistasis: genome-wide regulatory networks and network approaches to genome-wide association studies. WIREs Syst Biol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1002/wsbm.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Michor F, et al. What does physics have to do with cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:657–670. doi: 10.1038/nrc3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shepherd R, et al. Data mining using the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer BioMart. Database. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1093/database/bar018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]