Abstract

AIMS

This study examined the effects of the CYP3A/P-glycoprotein inducer, rifampicin, on the pharmacokinetics of dabigatran following oral administration of the prodrug, dabigatran etexilate.

METHODS

This was an open-label, fixed-sequence, four-period study in healthy volunteers. Subjects received a single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg on day 1, rifampicin 600 mg once daily on days 2–8, and single doses of dabigatran etexilate on days 9, 16 and 23.

RESULTS

Twenty-four subjects were treated, of whom 22 received all treatments. Relative to the reference (single dose of dabigatran etexilate alone; treatment A), administration of dabigatran etexilate following 7 days of rifampicin (treatment B) decreased the geometric mean (gMean) area under the concentration–time curve (AUC0–∞) and maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) of total dabigatran by 67 and 65.5%, respectively. The time to peak and the terminal half-life were not affected. The gMean ratio for the primary comparison (treatment B vs. treatment A) was 33.0% (90% confidence interval 26.5, 41.2%) for AUC0–∞ and 34.5% (90% confidence interval 26.9, 44.1%) for Cmax, indicating a significant effect on total dabigatran exposure (total pharmacologically active dabigatran represents the sum of nonconjugated dabigatran and dabigatran glucuronide). After a 7 day (treatment C) or 14 day washout (treatment D), the AUC0–∞ and Cmax of dabigatran were reduced by 18 and 20%, and by 15 and 20%, respectively, compared with treatment A, which was considered not clinically relevant. The overall safety profile of all treatments was good.

CONCLUSIONS

Administration of rifampicin for 7 days resulted in a significant reduction in the bioavailability of dabigatran, which returned almost to baseline after 7 days washout.

Keywords: dabigatran etexilate, drug interaction, P-glycoprotein, rifampicin

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Dabigatran etexilate is an oral prodrug that is rapidly converted to dabigatran, a direct and reversible thrombin inhibitor.

Dabigatran etexilate and dabigatran are not metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, and dabigatran does not affect the metabolism of other drugs that utilize this system, leading to a low potential for drug–drug interactions.

Dabigatran etexilate, but not dabigatran, is a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate, and the bioavailability of dabigatran may be altered by P-gp inhibitors or inducers.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Administration of rifampicin (a strong P-gp inducer) for 7 days before a single dose of dabigatran etexilate resulted in a significant reduction in the bioavailability of dabigatran compared with administration of dabigatran etexilate alone.

Within 7 days following the cessation of rifampicin administration, the bioavailability of dabigatran returned almost to baseline values.

Rifampicin is not recommended for use with dabigatran etexilate because of the potential for reduced systemic exposure to dabigatran.

Introduction

Dabigatran etexilate is an oral prodrug that is rapidly converted via two intermediates, BIBR 1087 SE and BIBR 951 BS, to the active moiety, dabigatran, a direct and reversible thrombin inhibitor. Dabigatran is partly conjugated with activated glucuronic acid to form a pharmacologically equipotent glucuronide. Free dabigatran and total dabigatran (sum of free and glucuronidated dabigatran) reach peak plasma concentrations after approximately 1.5 h, have a half-life of 12–17 h and are predominantly excreted (>80%) via the kidneys [1–6].

Dabigatran etexilate is licensed for the prevention of venous thromboembolic events following total hip or knee replacement and has more recently been approved and marketed for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation [7–9]. Dabigatran etexilate is administered orally, is not associated with clinically relevant food interactions and has dose-proportional and linear pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) [2, 3, 10–13].

Dabigatran etexilate and dabigatran are not metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, and dabigatran does not affect the metabolism of other drugs that utilize this system [2, 14–16]. However, preclinical and clinical studies have shown that dabigatran etexilate (but not dabigatran) is a P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate, and therefore the bioavailability of dabigatran following oral administration of dabigatran etexilate may be altered by P-gp inhibitors [17, 18]. For example, its bioavailability is increased in patients taking strong P-gp inhibitors, such as quinidine, verapamil and amiodarone.

The antibacterial agent rifampicin (used primarily in the treatment of tuberculosis) is a strong inducer of intestinal and hepatic P-gp. It also induces a number of drug-metabolizing enzymes, having the greatest effects on the expression of CYP3A in the liver and small intestine [19, 20].

The primary objective of the trial was to determine whether, and to what extent, the P-gp inducer, rifampicin, affects the plasma exposure of dabigatran by investigating the effect of multiple doses of rifampicin 600 mg once daily on the PK parameters of dabigatran following a single dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate. The study also evaluated the time course of a return to normal availability of dabigatran, which could be interpreted as normal activity levels of P-gp after induction by rifampicin. The doses selected for investigation reflect standard clinical doses of rifampicin and dabigatran etexilate, and were expected to allow an adequate determination of the PK parameters of dabigatran after P-gp induction. The induction by rifampicin was to be confirmed further by measurement of a surrogate end-point, the urinary 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio. This ratio is thought to reflect the CYP3A activity and has proved to be a good marker for CYP3A induction [21].

The secondary objectives were to determine the safety and tolerability of dabigatran and rifampicin coadministration, and to determine the duration of the effect of P-gp induction after cessation of rifampicin treatment. If an interaction between rifampicin and dabigatran was observed, it was expected that this would lead to decreased dabigatran exposure.

Methods

Study design and treatments

This study was an open-label, four-period, fixed-sequence trial performed in healthy male and female subjects to investigate the relative bioavailability of dabigatran etexilate given as single doses, either alone or after multiple doses of rifampicin, or after cessation of rifampicin. Twenty-four subjects were to be enrolled, with at least eight of each sex. The trial was conducted at CRS Clinical Research Services Mannheim GmbH (Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), after approval by the local independent ethics committee (IEC). The trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Ingelheim, Germany.

Dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa®; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG) was administered as 150 mg hydroxypropyl methylcellulose capsules. Rifampicin was administered as the commercially available Rifa® 600 mg coated tablets (Grünenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany).

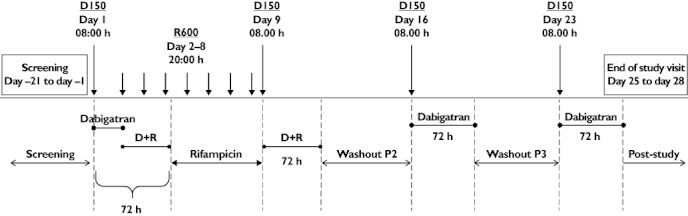

The subjects received single oral doses of dabigatran etexilate (150 mg), always in the morning at 08.00 h, during the following four treatment periods (Figure 1): period 1 (treatment A), dabigatran etexilate 150 mg administered on day 1 (reference); period 2 (treatment B), rifampicin 600 mg once daily administered for 7 days (days 2–8) in the evening at 20.00 h, with the last dose of rifampicin given 12 h before dabigatran etexilate 150 mg administered on day 9 (test 1); period 3 (treatment C), a single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg administered on day 16 after 7 days of rifampicin washout (test 2); and period 4 (treatment D), a single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg administered on day 23 after 14 days of rifampicin washout (test 3).

Figure 1.

Administration of trial medication (upper half of the diagram) and definition of treatment periods for safety analyses (lower half of the diagram). Dabigatran etexilate was always given in the morning at 08.00 h. Rifampicin was always administered in the evening at 20.00 h, with the last dose given 12 h before the dabigatran etexilate test treatment on day 9. D150, dabigatran etexilate 150 mg; R600, rifampicin 600 mg; D+R, dabigatran etexilate + rifampicin; P2, P3, period 2, period 3.

A screening examination (visit 1) was performed between days −21 and −1. Washout periods between subsequent dabigatran etexilate doses were included between the study days (days 1, 9, 16 and 23). The end-of-trial examination was scheduled between days 25 and 28 (time window).

Subjects

Healthy male and female subjects [based upon complete medical history, physical examination, vital signs (blood pressure and pulse rate), 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), clinical and laboratory tests], aged ≥18–45 years, with a body mass index between ≥18.5 and ≤29.9 kg m−2, were included in the trial. Participants gave their written informed consent in accordance with GCP and local legislation.

The exclusion criteria included any of the following: gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, respiratory, cardiovascular, metabolic, immunological or hormonal disorders, risk of bleeding, previous use of rifampicin or other P-gp or CYP450 inhibitors/inducers within 4 weeks prior to the start of treatment.

Study end-points

The primary PK end-points were area under the concentration–time curve (AUC0–∞) and maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) of total dabigatran (free plus conjugated). The primary comparison was between treatment B (single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg after multiple doses of rifampicin 600 mg) vs. reference treatment A (single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg before any rifampicin treatment), with α-adjustment of the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of AUC0–∞ and Cmax to account for multiple testing of two correlated primary end-points [22].

Further comparisons were performed between treatment C (single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg after 7 days of washout since last intake of rifampicin 600 mg) and reference treatment A, and between treatment D (single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg after 14 days washout after the last intake of rifampicin 600 mg) and reference treatment A.

The secondary PK end-points included AUC0–∞ and Cmax of free dabigatran, and Cmax and time from dosing to maximal plasma concentration (tmax) of total dabigatran. The ratio of urinary concentrations of 6β-hydroxycortisol to cortisol as a marker of induction of CYP3A4 by rifampicin and an evaluation of safety were other secondary end-points.

Pharmacokinetic determinations

Blood samples for dabigatran PK measurements were collected before (−0.5 h) and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24 and 34 h after administration of a single dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate in each treatment period. Plasma concentrations of free, nonconjugated dabigatran, total dabigatran [sum of free and conjugated dabigatran (measured after alkaline cleavage of conjugates)], the prodrug, dabigatran etexilate, and the intermediate metabolites, BIBR 1087 SE and BIBR 951 BS, were determined by a validated high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) method at AAI Pharma Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Neu-Ulm, Germany.

Briefly, plasma was prepared from EDTA blood (at 2000g–4000g for 10 minutes); for the determination of free dabigatran, 50 µl of plasma was aliquoted, diluted with 50 µl 0.2 m ammonium formate buffer (pH 3.5), spiked with 40 µl internal standard solution (100 ng ml−1[13C6]dabigatran), mixed and centrifuged. For the determination of total dabigatran, 50 µl of plasma was aliquoted, spiked with 40 µl internal standard solution and mixed with 20 µl 0.2 m sodium hydroxide. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the samples were acidified with 30 µl 0.2 m hydrochloric acid, mixed and then centrifuged.

For each determination, an aliquot of the resulting supernatant was transferred into autosampler vials. The analytes were extracted by column switching and were chromatographed on an analytical C18 reversed phase HPLC column with gradient elution.

The lowest limit of quantification of free or total dabigatran was 1 ng ml−1, the inaccuracy was at maximum −5.37% (at 3 ng ml−1 nominal dabigatran concentration), and the imprecision was always <9%. The limit of quantification was also 1 ng ml−1 for the prodrug (dabigatran etexilate) and the intermediate metabolites, BIBR 1087 SE and BIBR 951 BS. The inaccuracy was highest with BIBR 1087 SE (–16.23 and −7.75% at 3 and 9 ng ml−1 spike concentrations, respectively); imprecision was always <10%.

In addition, total dabigatran urine concentrations were measured. The calibration range was between 20 and 1000 ng ml−1, and the analyses were performed with high accuracy (inaccuracy <2%) and precision (imprecision <7%).

The 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio, an established marker of human hepatic CYP450 3A induction (but not a marker for P-gp activity), was assessed in morning spot urine samples collected within 4 h after the complete first morning voids, but before drug administration at the latest (typically 30 min before). Samples were taken in the morning after subjects had received three doses of rifampicin during treatment B and before administration of dabigatran in each respective treatment period. Thus, morning spot urine samples were collected at baseline, day 1 (period 1), days 5 and 9 (period 2), day 16 (period 3) and day 23 (period 4).

Urinary concentrations of cortisol and 6β-hydroxycortisol were analysed by an HPLC-MS/MS method at SGS Cephac Europe, St Benoît, France. The calibration curves for 6β-hydroxycortisol and cortisol ranged between 1–1000 and 10–3000 ng ml−1, respectively. The assay had a low interday inaccuracy and imprecision of <11 (6β-hydroxycortisol) and 13% (cortisol) at all spiked concentrations. Induction of CYP3A by rifampicin was assessed by the change in the ratio of 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol after a 7 day treatment of 600 mg rifampicin once daily and after cessation of rifampicin, compared with the ratio at baseline before the administration of rifampicin.

Safety

Safety was assessed by medical examination, pulse rate, blood pressure, 12-lead ECG, laboratory parameters, and the occurrence and severity of adverse events (AEs). The investigator assessed tolerability based on AEs and the laboratory evaluation according to the categories ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘not satisfactory’ and ‘bad’.

Statistical methods

Point estimators (geometric means; gMeans) of the median intrasubject ratios of AUC0–∞ and Cmax were calculated. The statistical model was an analysis of variance model on log-transformed parameters, including effects for ‘subject’ and ‘treatment’. However, a confidence interval for the relative bioavailability that does not contain the value 100% is equivalent to an effect significantly different from zero. Confidence intervals were based on the residual error from the investigated treatment comparison. Descriptive statistics for all other parameters were calculated.

Results

Study population

A total of 24 healthy volunteers entered the study and were treated; 10 (41.7%) were male and 14 (58.3%) female. All subjects were Caucasian. Their mean age was 32.9 years (range 22–44 years), with a mean body mass index of 25.1 kg m−2. Two subjects discontinued treatment prematurely (withdrew consent due to personal reasons); however, these subjects underwent the end-of-trial visit. The 22 subjects who completed treatment as planned received dabigatran etexilate 150 mg for 4 days (1 day in each treatment period) and rifampicin 600 mg for 7 days (period 2); the other two subjects received dabigatran etexilate 150 mg for 2 days (1 day in the first two treatment periods) and rifampicin 600 mg for 7 days (period 2).

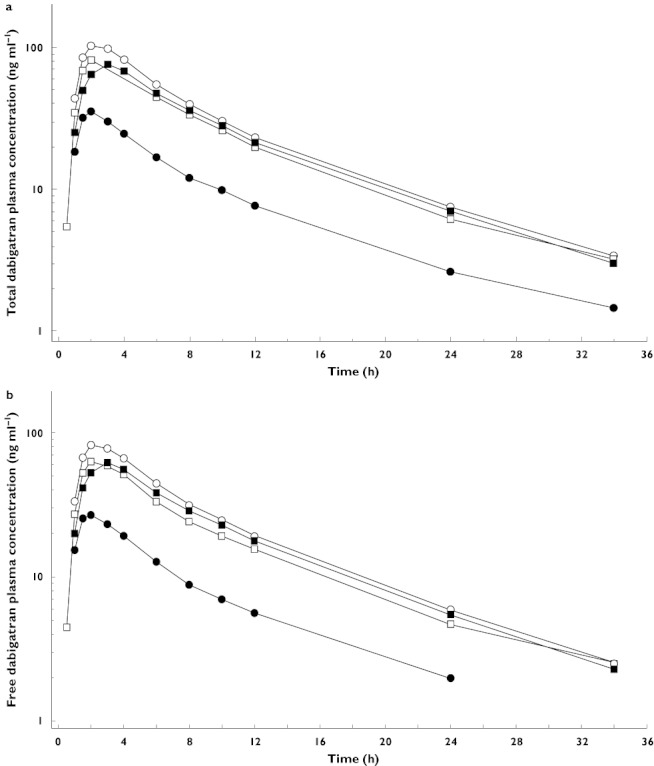

Pharmacokinetic parameters

The shapes of the plasma concentration–time profiles of free and total dabigatran were highly comparable, as shown in Figure 2. The PK parameters of total dabigatran after administration of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg, with and without rifampicin, are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Geometric mean (gMean) plasma concentration–time profiles (semi-logarithmic scale) of total (a) and free dabigatran (b) after a single oral dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate on day 1 (reference; treatment A), on day 9 after administration of multiple doses of 600 mg rifampicin (test 1; treatment B), on day 16, i.e. 7 days after last rifampicin administration (test 2; treatment C) and on day 23, i.e. 14 days after last rifampicin administration (test 3; treatment D). Day 1 (period 1, reference) (N = 24) ( ); Day 9 (period 2, test) (N = 24) (

); Day 9 (period 2, test) (N = 24) ( ); Day 16 (period 3, test) (N = 22) (

); Day 16 (period 3, test) (N = 22) ( ); Day 23 (period 4, test) (N = 22) (

); Day 23 (period 4, test) (N = 22) ( )

)

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of total dabigatran after administration of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg, with and without rifampicin

| Treatment A: 150 mg DE day 1 (n = 24) | Treatment B: 150 mg DE day 9 and multiple doses of rifampicin (n = 24) | Treatment C: 150 mg DE day 16, 7 days after rifampicin (n = 22) | Treatment D: 150 mg DE day 23, 14 days after rifampicin (n = 22) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | |

| AUC0–24 (ng h ml−1) | 813 | 61.5 | 265 | 52.3 | 668 | 69.6 | 690 | 69.6 |

| AUC0–tz (ng h ml−1) | 862 | 61.8 | 274 | 57.2 | 705 | 71.5 | 734 | 69.8 |

| AUC0–∞ (ng h ml−1) | 899 | 60.0 | 297 | 48.3 | 736 | 70.1 | 767 | 68.5 |

| %AUCtz–∞ (ng h ml−1) | 3.80 | 42.0 | 5.94 | 65.5 | 3.92 | 40.4 | 3.95 | 36.8 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 110 | 69.0 | 37.9 | 72.0 | 87.7 | 68.6 | 88.4 | 75.6 |

| tmax (h)* | 2.00 | 1.50–3.00 | 2.00 | 1.5–4.00 | 2.00 | 1.00–3.00 | 2.50 | 1.5–6.00 |

| t1/2 (h) | 7.40 | 10.6 | 7.76 | 17.8 | 7.13 | 14.0 | 7.3 | 11.8 |

| CL/F (ml min−1) | 2090 | 60.0 | 6320 | 48.3 | 2550 | 70.1 | 2450 | 68.5 |

| Ae0–24 (µg) | 3350 | 65.3 | 1100 | 67.1 | – | – | – | – |

| fe0–24 (%) | 2.97 | 65.3 | 0.981 | 67.1 | – | – | – | – |

| CLR0–24 (ml min−1) | 68.6 | 29.7 | 69.5 | 25.5 | – | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: Ae0–24, amount eliminated in urine; AUC0–∞, area under the concentration–time curve; AUC0–tz, area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to last quantifiable plasma concentration; Cmax, maximal plasma concentration; CL/F, apparent clearance; CLR0–24, 0–24 h renal clearance; DE, dabigatran etexilate; gCV, geometric coefficient of variation; gMean, geometric mean; fe0–24, fraction of administered drug excreted in urine; tmax, time from dosing to maximal plasma concentration; and t1/2, terminal half-life. *Median (range).

Relative to the reference treatment (dabigatran etexilate alone), the administration of the P-gp inducer, rifampicin, over 7 days (treatment B) resulted in a significant reduction in the exposure to total dabigatran (67% reduction in AUC0–∞ and 65.5% reduction in Cmax) on day 9 (treatment B) in comparison with day 1 (treatment A; Table 2). The gMean ratio for the primary comparison was 33.0% (90% CI 26.5, 41.2%) for the AUC0–∞ and 34.5% (90% CI 26.9, 44.1%) for the Cmax. After adjustment of the CIs for multiple comparisons, the lower and upper limit of the CIs were 25.9 and 42.1%, respectively, for the AUC0–∞, and 26.2 and 45.2%, respectively, for Cmax. Results indicated a statistically significant (P < 0.05) effect of rifampicin on the total dabigatran exposure.

Table 2.

Geometric means (gMeans) and relative bioavailability for intra-individual comparisons of a single dose of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg given alone (reference; treatment A) and after administration of multiple doses of rifampicin (test 1; treatment B)

| Total dabigatran | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment B: test 1 (n = 24) | Treatment A: reference (n = 24) | gMean ratio | 90% CI | Intra-individual gCV (%) | |

| gMean | gMean | test/reference (%) | |||

| AUC0–∞ (ng h ml−1) | 297 | 899 | 33.0 | 26.5, 41.2* | 47.1 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 37.9 | 110 | 34.5 | 26.9, 44.1* | 53.4 |

Abbreviations: AUC0–∞, area under the concentration–time curve; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximal plasma concentration; gCV, geometric coefficient of variation; and gMean, geometric mean. *Significant, with P < 0.05.

The time to peak (tmax) and the terminal half-life (t1/2) were not affected by rifampicin administration. The tmax, t1/2, mean residence time after oral administration values and the shape of the plasma concentration–time curve were similar between treatments A and B.

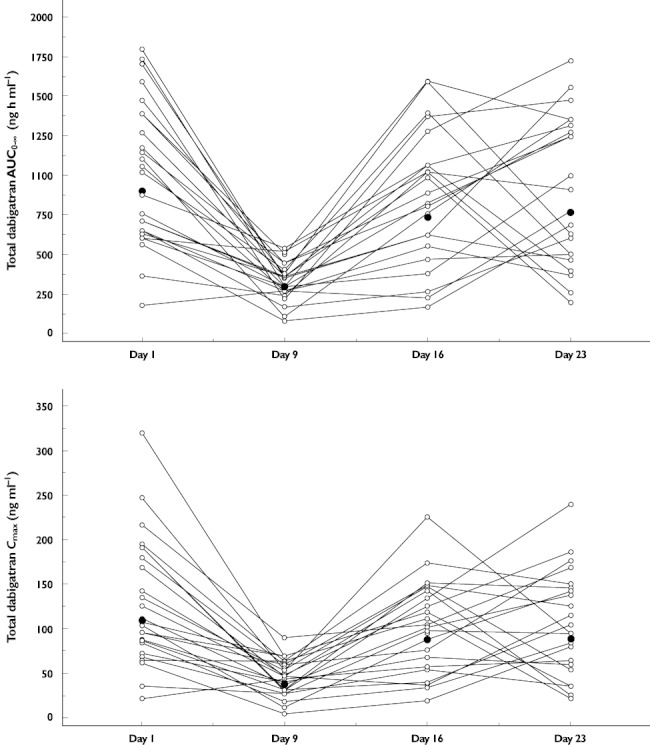

For the single dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate after a 7 day washout after the last dose of rifampicin (treatment C, day 16), AUC0–∞ and Cmax values were reduced by 18 and 20%, respectively, compared with the reference, treatment A. The gMean ratio of treatment C and the reference treatment was 82.3% (90% CI 65.3, 103.9%) for the AUC0–∞ and 81.4% (90% CI 65.2, 101.5%) for Cmax. Fourteen days after the last administration of rifampicin (treatment D, day 23), the AUC0–∞ and Cmax values were reduced by 15 and 20%, respectively, compared with the reference. The gMean ratio of treatment D and the reference treatment was 85.7% (90% CI 67.7, 108.5%) for the AUC0–∞ and 81.6% (90% CI 63.1, 105.6%) for Cmax. Intra-individual comparisons of the exposure parameters, AUC0–∞ and Cmax, between all treatments are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Intra-individual comparisons of AUC0–∞ (upper panel) and Cmax (lower panel) of total dabigatran after a single oral dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate alone on day 1 (treatment A) or 1, 7 or 14 days after the last administration of rifampicin 600 mg once daily given for 7 days (treatments B, C and D; days 9, 16 and 23, respectively). Individual data ( ); gMean (n = 24/24/22/22) (

); gMean (n = 24/24/22/22) ( )

)

For reference treatment A (day 1), male subjects had approximately 76% of the AUC0–∞ and 67% of the Cmax of female subjects in the trial. Following the administration of rifampicin over 7 days, the reduction in total dabigatran exposure was similar in male and female subjects.

The PK parameters of free dabigatran followed the same trend as those of total dabigatran (Figure 2b), and the ratio between total and free dabigatran AUC0–∞ was not modulated by rifampicin administration. Furthermore, the prodrug (dabigatran etexilate) and the intermediate metabolites (BIBR 951 BS and BIBR 1087 SE) were affected in the same way as dabigatran (Table 3). As the concentrations (only Cmax could be evaluated) were already rather small in the reference treatment, no quantitative assessment of the extent of reduction was feasible.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of prodrug (dabigatran etexilate) and intermediate metabolites (BIBR 1087 SE and BIBR 951 BS) after administration of dabigatran etexilate 150 mg, with and without rifampicin

| Treatment A: 150 mg DE day 1 | Treatment B: 150 mg DE day 9 and multiple doses of rifampicin | Treatment C: 150 mg DE day 16, 7 days after rifampicin | Treatment D: 150 mg DE day 23, 14 days after rifampicin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | gMean | gCV, % | |

| Dabigatran etexilate | ||||||||

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 3.64 | 72.0 | 2.32 | 43.7 | 3.38 | 59.3 | 3.58 | 60.3 |

| tmax (h)* | 1.00 | 0.500–2.00 | 0.500 | 0.500–1.50 | 1.00 | 0.500–1.50 | 1.00 | 0.500–2.00 |

| BIBR 1087 SE | ||||||||

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 2.07 | 40.7 | – | – | 1.67 | 35.6 | 1.93 | 37.0 |

| tmax (h)* | 1.00 | 1.00–2.00 | – | – | 1.00 | 0.500–1.50 | 1.50 | 0.500–2.00 |

| BIBR 951 BS | ||||||||

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 2.75 | 67.2 | – | – | 1.86 | 44.6 | 2.14 | 28.1 |

| tmax (h)* | 1.50 | 1.00–3.00 | – | – | 1.50 | 1.00–2.00 | 1.50 | 1.00–2.00 |

Abbreviations: Cmax, maximal plasma concentration; DE, dabigatran etexilate; and tmax, time from dosing to maximal plasma concentration. *Median (range).

6β-Hydroxycortisol/cortisol urine ratios

Compared with day 1, the urinary 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio on day 9 was increased approximately 5.6-fold, from a gMean (gCV %) 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio of 3.92 (65.3) to 22.0 (48.5), indicating CYP450 3A induction as a result of rifampicin administration. The urinary 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio was still slightly elevated on day 16 (∼1.2-fold), but had returned to baseline by day 23, 2 weeks after the end of treatment with rifampicin.

Safety

All 24 subjects who received at least one dose of study drug were included in the safety evaluation.

Only two (8.3%) subjects reported any AEs during treatment with dabigatran etexilate alone, four (16.7%) subjects during treatment with dabigatran etexilate plus rifampicin and two (8.3%) subjects during treatment with rifampicin alone (Table 4). In addition, one subject (4.5%; 1 of 22) reported an AE during the washout period after treatment period 3.

Table 4.

Number (%) of subjects with adverse events reported during treatment with dabigatran etexilate (excluding washout periods)

| Treatment periods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DE alone | DE plus rifampicin | Rifampicin | |

| Number of subjects (%) | 24 (100) | 24 (100) | 24 (100) |

| Any AE | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| Severe AEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drug-related AEs | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| Other significant AEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious AEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; and DE, dabigatran etexilate.

The most frequently reported AEs were nervous system disorders, with headache the most common (dabigatran, two subjects; rifampicin, one subject; and dabigatran plus rifampicin, three subjects). No other AEs were reported during treatment with dabigatran alone. Other AEs reported were vertigo and hyperhidrosis (one subject each) during the dabigatran plus rifampicin period; dizziness, nausea, oropharyngeal pain, vomiting and fatigue (one subject each) during the rifampicin alone period; and nausea (one subject) during the washout after period 3.

All AEs were of mild or moderate intensity and resolved by the end of the trial. There were no deaths, other serious AEs, other significant AEs, severe AEs or AEs that led to discontinuation of study treatment.

Vital signs, ECG and safety laboratory assessments did not indicate any relevant, consistent or treatment-related untoward reactions. Global clinical tolerability was good in all subjects.

Discussion

Preclinical investigations have shown that dabigatran etexilate (but not dabigatran or its intermediate metabolites) is a substrate for the efflux transporter protein P-gp. Previous investigations suggest that the bioavailability of dabigatran may be affected by P-gp inhibitors [23]. In this study, a 1 week course of rifampicin, a potent inducer of P-gp, decreased exposure to dabigatran by 67%.

The approved dabigatran etexilate dose for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation is 150 mg twice daily for most patients [7, 8]. The present study investigated dabigatran etexilate 150 mg with or without rifampicin 600 mg once daily. These doses were selected because they reflected standard clinical doses, and the plasma concentrations of dabigatran and rifampicin in this trial represent clinically relevant drug exposure. The selected dosing regimen for rifampicin (7 day treatment with cessation of treatment the evening, i.e. 12 h, before administration of dabigatran etexilate) allowed for a test of maximal induction of P-gp without interference of inhibiting effects, because rifampicin was stopped after the last dose given in the evening before dabigatran administration. A single dose of dabigatran etexilate was considered to be representative of the effect following multiple dosing, potentially overestimating, rather than underestimating, the effect. In conclusion, the selected doses were expected to allow adequate determination of the PK parameters of dabigatran after P-gp induction.

In this study, the administration of rifampicin for 7 days resulted in a significant and relevant reduction in the bioavailability of total dabigatran (67 and 65.5% reduction in AUC0–∞ and Cmax values of total dabigatran, respectively) after administering a single oral dose of 150 mg dabigatran etexilate in healthy volunteers. Within 7 days following the cessation of rifampicin administration, the bioavailability of total dabigatran returned almost to baseline values. Pharmacokinetic parameters of free dabigatran were influenced in a similar fashion.

In the present trial, rifampicin administration also induced CYP3A, as shown by an elevated urinary 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio [24]. Such induction has been documented to dissipate in about 2 weeks after discontinuation of rifampicin [25]. Indeed, in this trial, the urinary 6β-hydroxycortisol/cortisol ratio was found to be only 1.2-fold higher than baseline values after 1 week and had returned to baseline levels 2 weeks after discontinuation of treatment with rifampicin. The effect on dabigatran was highly comparable, which seems physiologically reasonable because both CYP3A4 and P-gp share the same induction pathway via the transcription factor pregnane X receptor [26].

The reduction of the total dabigatran exposure after rifampicin pretreatment seen in this trial was of similar magnitude or only slightly exceeded the effects reported for digoxin [27], a prototypical P-gp substrate, or aliskiren [28]. Interestingly, despite a 56% reduction in the AUC0–∞ of aliskiren or a 58% reduction in Cmax of digoxin after rifampicin treatment, the renal clearance and half-life of these drugs always remained unaffected [27, 28]. This is in perfect agreement with the results reported in this study for dabigatran.

Dabigatran etexilate is assumed to be absorbed mainly in the duodenum. The pronounced effect of rifampicin on dabigatran kinetics might, thus, be due to a remarkable increase in duodenal P-gp expression (about a threefold increase) after rifampicin, as reported ex vivo[27] and in vitro[26]. An approximately 66% reduction in bioavailability by P-gp induction may be physiologically plausible for dabigatran etexilate, whose absorption (besides solubility limitations) is solely dependent on the efflux transporter P-gp. Moreover, recent in vitro data have clearly demonstrated that dabigatran has no affinity to any efflux (P-gp, BCRP and MRP2) or uptake transporter (OAT1, OAT3, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OATP2B1, OCT1 and OCT2), and that among intestinal transporters, P-gp only recognized dabigatran etexilate as substrate [29]. The reduced bioavailability of dabigatran after P-gp induction contrasts with the effect observed (an increase in exposure) when dabigatran is administered with a P-gp inhibitor. For example, the administration of the strong P-gp inhibitor ketoconazole increased the AUC0–∞ and Cmax of dabigatran by approximately 150% compared with dabigatran alone [23].

In the present trial, male subjects receiving reference treatment A on day 1 had approximately 76% of the AUC0–∞ and 67% of the Cmax values of the female subjects investigated. Although there were sex differences in exposure to total dabigatran, administration of rifampicin for 7 days resulted in a similar percentage reduction in total dabigatran exposure for male and female subjects.

The overall safety profile of all treatments was favourable. Dabigatran etexilate was well tolerated when given alone and in combination with rifampicin. The results were in line with the known safety profile of dabigatran etexilate.

A reduction of two-thirds in dabigatran exposure due to a 1 week course of rifampicin has clinically relevant consequences. Patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery who receive dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of venous thromboembolism may not achieve therapeutic concentrations of dabigatran if they have received rifampicin immediately before surgery. Dabigatran etexilate is also indicated for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. As a dose–response in stroke reduction has been demonstrated for dabigatran etexilate [13], the significant decrease in dabigatran exposure observed with rifampicin is likely to decrease the potential for stroke prevention. Concomitant treatment with rifampicin and dabigatran should be avoided in these patients. The effect of concomitant administration of dabigatran etexilate with other P-gp inducers, such as carbamazepine, diphenylhydantoin and St John's wort has not been tested. However, it should be emphasized that vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, show comparable liabilities when coadministered with compounds increasing warfarin clearance, such as carbamazepine, barbiturates, rifampicin and chronic alcohol [30]. Furthermore, the new factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban are expected to be affected by inducers of the rifampicin type because their clearance is dependent to a large extent on CYP3A4 and partly also on P-gp [18, 31].

In summary, the administration of rifampicin, a P-gp inducer, for 7 days resulted in a statistically significant and potentially clinically relevant reduction in the bioavailability of a single oral dose of dabigatran etexilate in healthy volunteers. Within 7 days following the cessation of rifampicin administration, the bioavailability returned almost to baseline values. Owing to the potential for reduced systemic exposure to dabigatran, rifampicin and other P-gp inducers (e.g. carbamazepine and St John's wort) are not recommended for use with dabigatran etexilate [32].

Acknowledgments

The study was exclusively sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG. The study was conducted at CRS Clinical Research Services Mannheim GmbH (principal investigator: Wolfgang Timmer) under the responsibility of the sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pharma GmbH & Co. KG. Writing and editorial support was provided by PAREXEL MMS and was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved at all stages of manuscript development.

Competing Interests

SH, MK-B, AS, GN, UL and PAR are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stangier J, Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Ahnfelt L, Nehmiz G, Stähle H, Rathgen K, Svärd R. Pharmacokinetic profile of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabagitran etexilate in healthy volunteers and patients undergoing total hip replacement. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:555–63. doi: 10.1177/0091270005274550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blech S, Ebner T, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Stangier J, Roth W. The metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:386–99. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, Gansser D, Roth W. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stangier J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:285–95. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stangier J, Stähle H, Rathgen K, Fuhr R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the direct oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:47–59. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, Mazur D. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259–68. doi: 10.2165/11318170-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehringer Ingelheim, Burlington, ON. Pradax™ Product Monograph [Internet] 2012. Available at http://webprod3.hc-sc.gc.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=eng&code=84384 (last accessed 28 February 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDA [Internet] Pradaxa label. 2010. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022512s000lbl.pdf (last accessed 6 April 2011)

- 9.Biotech Pharma News [Internet] Boehringer Ingelheim: PRAZAXA (dabigatran etexilate) approved in Japan for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. 2011. Available at http://www.biotechpharmanews.com/news/37-jan-2011/634-boehringer-ingelheim-prazaxa-dabigatran-etexilate-approved-in-japan-for-stroke-prevention-in-atrial-fibrillation.html (last accessed 28 February 2012)

- 10.Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Rosencher N, Kurth AA, van Dijk CN, Frostick SP, Kälebo P, Christiansen AV, Hantel S, Hettiarachchi R, Schnee J, Büller HR (RE-MODEL Study Group) Oral dabigatran etexilate vs. subcutaneous enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee replacement: the RE-MODEL randomized trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2178–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson BI, Dahl OE, Rosencher N, Kurth AA, van Dijk CN, Frostick SP, Prins MH, Hettiaracchi R, Hantel S, Schnee J, Büller HR. Dabigatran etexilate versus enoxaparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip replacement: a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2007;370:949–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson B, Dahl OE, Huo MH, Kurth AA, Hantel S, Hermansson K, Prins MH, Hettiarachchi R, Hantel S, Schnee J, Büller HR (RE-NOVATE Study Group) for the RE-NOVATE II Study Group: oral dabigatran versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after primary total hip arthroplasty (RE-NOVATE II) Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:721–9. doi: 10.1160/TH10-10-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L (RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stangier J, Stähle H, Rathgen K, Reseski K, Kornicke T. Coadministration of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate and diclofenac has little impact on the pharmacokinetics of either drug. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 2) Abstract P-W-677. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stangier J, Stähle H, Rathgen K, Reseski K, Körnicke T. No interaction of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate and digoxin. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 2) Abstract P-W-672. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, Reseski K, Körnicke T, Roth W. Coadministration of dabigatran etexilate and atorvastatin: assessment of potential impact on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2009;9:59–68. doi: 10.1007/BF03256595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, CT. Pradaxa® US prescribing information [Internet] 2012. Available at http://bidocs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/BIWebAccess/ViewServlet.ser?docBase=renetnt&folderPath=/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Pradaxa/Pradaxa.pdf (last accessed 28 February 2012)

- 18.Ufer M. Comparative efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban in preclinical and clinical development. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:572–85. doi: 10.1160/TH09-09-0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backman JT, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. Rifampin drastically reduces plasma concentrations and effects of oral midazolam. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backman JT, Kivisto KT, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve for oral midazolam is 400-fold larger during treatment with itraconazole than with rifampicin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:53–8. doi: 10.1007/s002280050420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galteau MM, Shamsa F. Urinary 6beta-hydroxycortisol: a validated test for evaluating drug induction or drug inhibition mediated through CYP3A in humans and in animals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:713–33. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pocock SJ, Geller NL, Tsiatis AA. The analysis of multiple endpoints in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1987;43:487–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Advisory Committee Briefing Document [Internet] Dabigatran etexilate. 2010. Boehringer Ingelheim; Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM226009.pdf (last accessed 4 April 2011)

- 24.Tran JQ, Kovacs SJ, McIntosh TS, Davis HM, Martin DE. Morning spot and 24-hour urinary 6 beta-hydroxycortisol to cortisol ratios: intraindividual variability and correlation under basal conditions and conditions of CYP3A4 induction. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39:487–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemi M, Backman JT, Fromm MF, Neuvonen PJ, Kivisto KT. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin: clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:819–50. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A, Mugundu GM, Desai PB, Thummel KE, Unadkat JD. Intestinal human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 is an excellent model to study pregnane X receptor, but not constitutive androstane receptor, mediated CYP3A4 and multidrug resistance transporter 1 induction: studies with anti-human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1172–80. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greiner B, Eichelbaum M, Fritz P, Kreichgauer HP, von Richter O, Zundler J, Kroemer HK. The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:147–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tapaninen T, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Rifampicin reduces the plasma concentrations and the renin-inhibiting effect of aliskiren. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:497–502. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishimoto W, Ishiguro N, Saito A, Ebner T, Haertter S, Igarashi T. Characterization of drug transporters involved in the disposition of dabigatran etexilate and its active form, dabigatran. 9th Int Mtg Int Soc Study Xenobiotics (ISSX), Istanbul, 4–8 Sep 2010. Drug Metab Rev. 2010;42:293. Abstr P469. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moualla H, Garcia D. Vitamin K antagonists – current concepts and challenges. Thromb Res. 2011;128:210–15. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deloughery TG. Practical aspects of the oral new anticoagulants. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:586–90. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim. Pradaxa® summary of product characteristics [Internet] 2011. Available at http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20760/SPC/Pradaxa+110+mg+hard+capsules (last accessed 28 February 2012)