Abstract

To analyze the incidence of nerve sheath tumors in a tertiary care hospital over a period of 5 years and review the literature. Medical case records from last 5 years were retrieved and histopathology and operative details were studied in a retrospective analysis. There is a slight male preponderance when it comes to nerve sheath tumors and acoustic schwannomas accounted for the largest fraction among schwannomas. Nerve sheath tumors include a wide spectrum of schwannomas, neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Hence combination of clinical, pathological and surgical expertise is needed to diagnose accurately.

Keywords: Neurofibroma, Schwannoma, Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Introduction

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors present as soft tissue neoplasms and include the spectrum of schwannomas, neurofibromas, neurofibromatosis, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. The presentation varies from asymptomatic soft tissue swellings to large masses that are recurrent and difficult to excise.

Aims and Objectives

The aim of this analysis was to look at the incidence of nerve sheath tumors in a tertiary care hospital, to study the distribution of the benign and malignant variants, to analyze the clinical presentation, and to look at the demographics of the population.

Patients and Methods

This was a retrospective analysis done at Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute between January 2005 and January 2010 (a period of 5 years). Medical case records were retrieved and perused; histopathology files were studied and operative details were analyzed.

Demographics

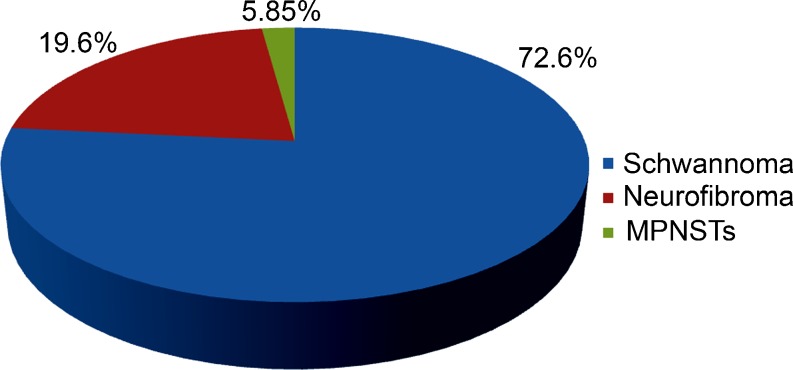

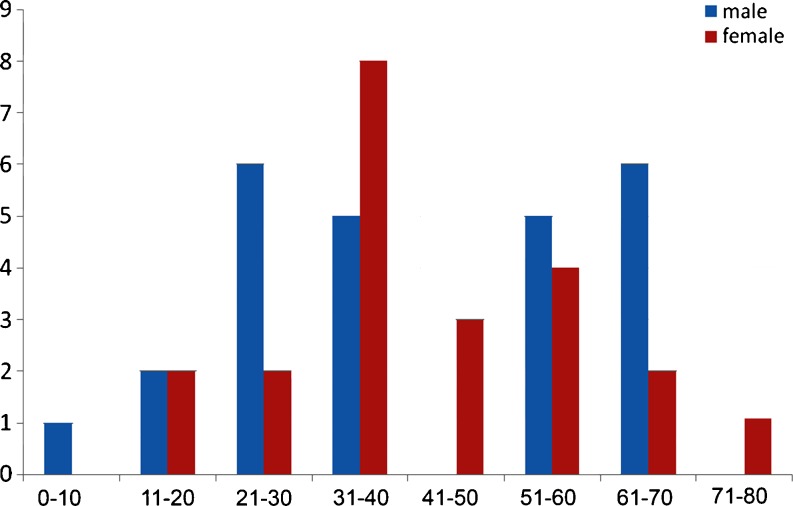

There were a total of 51 patients with nerve sheath tumors over a 5-year period, with a slight male preponderance (54.9%). A clustering of 25.4% was observed in the age group of 31–40 years. There were 37 patients with schwannomas, 10 patients with neurofibromas (1 with plexiform neurofibromatosis), and 3 patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (5.85%). Figure 1 shows the distribution of nerve sheath tumors, while Fig. 2 shows the demographics of the population.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of peripheral nerve sheath tumors in a sample size of 51 patients showing percentage incidences of schwannomas in blue (37, 72.55%), neurofibromas in red (10, 19.61%), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) in green (3, 5.85%)

Fig. 2.

Distribution of peripheral nerve sheath tumors according to demographics. There is a slight male preponderance (blue) compared to females (red). The Y-axis shows the number of cases and the X-axis shows the range of ages in years

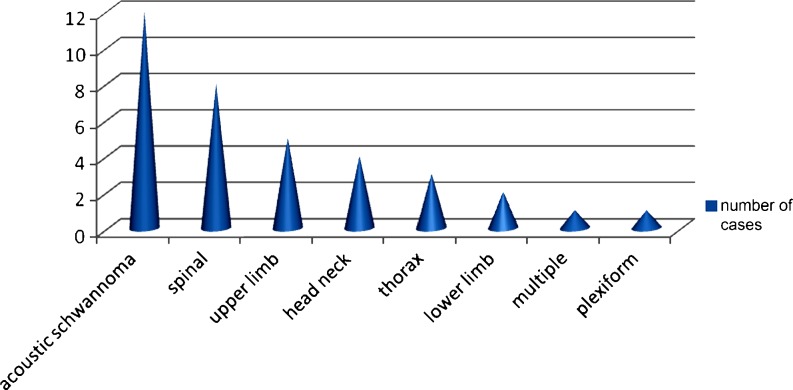

Acoustic schwannomas accounted for the largest fraction (25.53%) of the schwannomas followed by spinal schwannomas and others in locations such as the upper limb, the head and neck, and the lower limb. The schwannomas most often presented as painless soft tissue swellings with only a few presenting with paresthesia or tingling (24%). Acoustic neuromas which accounted for 25.53% of all schwannomas presented with hearing loss (33.3%), nerve palsy (33.3%), nystagmus, giddiness, and ataxia (8.2%). Based on histology some schwannomas were described as ancient (10.8%) and cellular (13.5%). Figure 3 shows the site of peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

Fig. 3.

Site distribution of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Acoustic schwannomas accounted for the largest fraction (25.53%) of the schwannomas followed by spinal schwannomas and others in locations such as the upper limb, head, and neck and the lower limb. The Y-axis shows the number of cases and the X-axis shows the site of occurrence

Neurofibromas accounted for 19.61% of all the nerve sheath tumors. This included one patient with plexiform neurofibromatosis occurring in von Recklinghausen disease, who presented with café au lait patches and multiple neurofibromatosis.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors were seen in a varied population (19/m, 30/m, 55/f) and accounted for less than 6% of the study population (the small sample size does not permit any meaningful conclusions).One was a malignant Triton tumor.

Discussion

Nerve sheath tumors are mostly benign (schwannomas, neurofibromas, neurofibromatosis) and sometimes malignant. The Schwann cell (the cell of origin for both schwannoma and neurofibroma) surrounds the axon. While a schwannoma is a tumor of differentiated Schwann cells, the neurofibroma represents a mixture of Schwann cells, perineural cells, fibroblasts, and trapped axons [1].

Schwannomas or neurilemmomas are encapsulated lesions that occur at any age (as solitary, multiple, or plexiform), but are commonly seen between 20 and 50 years. There is equal gender distribution. They have a predilection for the head, neck, and flexor surface of the extremities, often on small and medium-sized nerves. Schwannomas are most often solitary and multiple schwannomas are seen with neurofibromas in von Recklinghausen disease and in schwannomatosis [2]. Schwannomas can also be seen in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (including the plexiform growth pattern) and NF2.

Neurofibromas are unencapsulated nerve sheath lesions that occur as a solitary localized nodule or as a diffuse thickening of the skin and subcutaneous tissue and occasionally as a plexiform tumor with multinodular growth of the major and minor nerves. They are commonly seen in young adults.

Neurofibromatosis is an autosomal dominant single-gene disorder (mapped to a single chromosome). There are two distinct types of neurofibromatosis: NF1 or von Recklinghausen disease (occurring 1 in 3,000 individuals) which affect 85% of the patients mapped to 17q12. NF2 or bilateral acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma affects 10% of the patients (occurring 1 in 25,000 individuals) and is mapped to chromosome 22.

von Recklinghausen disease is diagnosed by the presence of any two of the following:

At least five café au lait spots larger than 5 mm (six larger than 15 mm if the patient is prepubertal)

Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform

Multiple freckles in the axillary and inguinal region

Sphenoid wing dysplasia

Bilateral optic nerve glioma

Multiple iris nodules (Lisch nodules)

First-degree relatives with above criteria

In NF1 discrete cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas develop often after puberty and range from a few to hundreds and even thousands. Intracranial manifestations of NF1 include optic pathway gliomas, cerebral gliomas, hydrocephalus, schwannomas of the cranial nerves, vascular dysplasia, hematomas, craniofacial plexiform neurofibromas, and spongiotic myelinopathy [3]. NF1 can involve the spine, musculoskeletal system, and gastrointestinal tract and be associated with neural crest tumors. The clinical presentation of NF1 is multisystemic and includes seizures, optic and acoustic involvement, increased incidence of malignancies and endocrine disorders, oral pathology, hypertension, and osseous defects [4].

NF2, an autosomal dominant syndrome, is characterized by multiple schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas. The most common lesion associated is the vestibulocochlear schwannoma [5]. The genetic abnormality noted is deletion of a small portion of chromosome 22. The clinical presentation of NF2 is due to the eighth nerve involvement and may be as varied as nerve palsy, tinnitus, ataxia, giddiness, and hearing loss or asymptomatic when small.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are present anywhere in the body. Those in peripheral locations are more solitary, non-NF type, central lesions on the trunk, head, neck are seen with NF1, and limb girdle regions are affected in either type [6].

Investigations

While the diagnosis of multiple neurofibromatosis is no challenge, the ability to recognize the occurrence in solitary and atypical locations requires clinical expertise. Computerized tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are excellent at depicting most primary lesions, associated tumors and complications of NF1 [7]. Optic nerve glioma and intraspinal abnormalities are better imaged with MRI. The diagnostic test for patients with acoustic tumors and spinal schwannomas is gadolinium-enhanced MRI as even fine slice CT cannot detect a tumor of size lesser than 1–1.5 cm. MRI shows an intermediate to moderate bright signal on T1-weighted images. All lesions are moderately bright on proton density and T2-weighted images. However, even with optic nerve gliomas, osseous erosions may be depicted better on CT scans. Figure 4 shows CT brain showing a right cerebellopontine angle tumor, possibly acoustic neuroma.

Fig. 4.

CT brain showing a right cerebellopontine angle tumor, possibly an acoustic neuroma

Treatment

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice in symptomatic neurofibromas and schwannomas even though there is a strong chance for postoperative nerve dysfunction [8]. Acoustic neuromas are managed in one of the following ways: surgical excision of the tumor, arresting tumor growth using stereotactic radiation therapy, or by careful serial observation [9]. Surgical resection of tumors remains the mainstay of treatment in NF2. For small vestibular schwannomas, both surgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery can be done. Larger tumors may require surgical resection despite irreversible hearing loss, especially when there is evidence of brainstem compression, facial nerve palsy, or in extreme cases, early hydrocephalus. Nonvestibular cranial nerve schwannomas are treated using a combination of microsurgery and radiosurgery. Bevacizumab (Avastin) is under trial for treatment of vestibular schwannomas in NF2 [10].

Histopathology

Schwannomas generally arise in larger nerves and present as eccentric masses. Grossly, they are solitary, well-circumscribed, encapsulated lesions. Cut surface appears solid, smooth, glistening and gray-white. It may show cystic and hemorrhagic areas with calcification. Histomorphology of schwannoma characteristically shows two alternating patterns—Antoni A and Antoni B areas. Antoni A are cellular areas with compactly arranged spindle cells frequently arranged in interlacing fascicles, palisades, or in an organoid arrangement, with two compact parallel rows of well-aligned nuclei forming eosinophilic structures (Verocay bodies). Antoni B exhibits hypocellular areas consisting of a few tumor cells in loose myxomatous matrix (Fig. 5, the left inset). They also show thick-walled blood vessels. There are several variants of schwannomas based on histological appearance, including cellular, glandular, epithelioid, and ancient types [11]. Other variants are also benign in nature. Cellular schwannomas are predominantly composed of Antoni A areas and lack Verocay bodies. Tumor cell nuclei and cytoplasm show strong positivity for S100 immunostain. The neoplastic cells also express vimentin and myelin basic protein. Ancient schwannomas are benign cellular tumors with bizarre hyperchromatic nuclei without mitoses. These features occur in longstanding tumors and represent degenerative change in tumors.

Fig. 5.

Histopathological features of schwannoma (a), neurofibromatosis (b), and MPNST (c)

Neurofibromas are grossly nodular/pedunculated, soft, and grayish white with usually no secondary degenerative changes. Histomorphology of neurofibroma shows a fairly well-circumscribed, yet unencapsulated tumor with predominantly spindle-shaped cells composed of proliferating fibroblasts, many schwann cells, and collagen fibers. There may be prominent myxomatous change (Fig. 5, the central inset). Distorted organoid structures resembling Wagner–Meissner or Pacini’s corpuscles are sometimes noted. Mitotic activity is usually scanty or absent. Schwann cells in the tumor show positivity for S100 protein.

In neurofibromatosis the lesions are multiple and show a more diffuse involvement of the affected tissue. Gross examination of skin shows firm plaque-like elevations with diffuse gray white thickening of dermis and subcutis. Microscopy shows ill-defined lesions with diffuse replacement of the dermis and subcutis by neurofibromatous tissue. The tumor shows similar cells and pattern of arrangement as neurofibroma with a more diffuse involvement. Characteristically, it encases the adnexal structures. Clusters of Meissner bodies and occasionally multinucleate giant cells may also feature [12].

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) are large tumors, usually more than 5 cm in diameter. The tumor grossly appears as a large fusiform mass arising from a major nerve. Cut surface of the tumor is solid, fleshy, and tan to whitish with focal areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopic examination reveals a cellular tumor composed of spindle cells arranged in interlacing bundles and fascicles [13]. It may also exhibit areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. Tumor cells show varying grades of cellular atypia and mitotic activity (Fig. 5, the right inset). It may also feature heterologous elements (another sarcomatous differentiation) such as osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, angiosarcoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma in about 15% cases (malignant triton tumor). Rarely, there may be foci of glandular differentiation. Variants of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor include myxoid, epithelioid, and pigmented (melanotic) MPNSTs. Immunohistochemistry plays an important role to confirm the neural nature of the tumor. Tumor cells show positivity for S100 protein (positive only in 50% cases). Neoplastic cells may show positivity for other neural markers such as neuron-specific enolase, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament. Heterologous elements show positivity with relevant immunostains [14].

In our study, we have two cases of MPNSTs in the lower limb and one trigeminal malignant triton tumor with intracranial extension. One of the lower limb MPNSTs associated with NF1 metastasized to the lungs.

Conclusion

Nerve sheath tumors have varied clinical presentations, and a systematic approach, with judicious use of imaging, histopathology, and immunochemistry, is needed for accurate diagnosis.

Contributor Information

Rekha Arcot, Phone: +91-044-22520256, Email: rekha_a@yahoo.com.

Kavitha Ramakrishnan, Email: kav.revram@gmail.com.

Shalinee Rao, Email: shalineerao@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Wesiss soft tissue tumors. 4. St Louis: London, Mosby; 2001. Benign tumors of the peripheral nerves and malignant tumors of the peripheral nerves; pp. 111–322. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chick G, Alnott JY, Silbermann Hoffmann O. Multiple peripheral nerve tumors—an update and review of literature. Chir Main. 2003;22(3):131–137. doi: 10.1016/S1297-3203(03)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mrugala MM, Batechlor TT, Plotkin RR. Peripheral and cranial nerve sheath tumors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(5):604–610. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000179507.51647.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral nerve sheath tumors—30-year experience at Louisana State University Health Sciences Centre. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2):246–255. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colreavy MP, Lacy PD, Hughes J, et al. Head and neck schwannomas—a 10-year review. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:119–124. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta G, Maniker A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(6):E12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.6.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stull MA, Moser RP, Jr, Kransdorf MJ, Bogumell GP, Nelson MC. Magnetic resonance appearance of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Skeletal Radi. 1991;20(1):9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00243714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levi AD, Ross AL, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Temple HT. The surgical management of symptomatic peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(4):833–840. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000367636.91555.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons CM, Canter RJ, Khatri VP. Surgical management of neurofibromatosis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18(1):175–196. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mautner VF, Nguyen R, Kutta H, Fuensterer C, Bokemeyer C, Hagel C, Friedrich RE, Panse J. Bevacizumab induces regression of vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Neuro Oncol. 2000;12(1):14–18. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kar M, Deo SV, Shukla NK, Malik A, Dattagupta S, Mohanti BK, et al. Clinico pathological study of treatment outcomes of 24 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NT, Homey B, Matuschek C, Pelper M, Budach W, Bolke E. Neurofibromatosis. Euro J Med Res. 2009;14(3):102–105. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-3-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulon A, Millin S, Laban E, Debrais C, Jamet C, Goujon JM. Pathologic characteristics of the most frequent peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurochirugie. 2009;55(4–5):454–458. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]