Abstract

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is widely used as oxidative stress biomarker in biomedical research. Plasma is stored in deep freezers generally till analysis. Effect of such storage on MDA values, which may be variable and prolong, was incidentally observed in the ongoing study which is to estimate oxidative stress with oral iron. Plasma from blood samples of pregnant women (20–30 years age) in third trimester of singleton pregnancy (n = 139), consuming oral iron tablets was stored at −20 °C with intention of MDA estimation, as soon as possible. However logistic problems led this storage for prolonged and variable period (1–708 days). When values of MDA estimated using “Ohkawa” 79 method and readings were plotted against time to check the temporal effect, it showed a hyperbolic curve. Standard deviation (SD) was lowest when samples were tested within 3 weeks time. The samples analyzed within 3 weeks had mean ± SD value of 31.59 ± 26.11 μmol/L, while 123.7 ± 93.97 and 366.5 ± 189.8 μmol/L for samples stored for 1–3 and 4 months to 1 year respectively. Mean ± SD were 539.9 ± 196.8 in the samples store for more than a year. Rate of change in values was also lowest (0.0433 μmol/L/day) in the samples tested within first 3 weeks, which rose to 1.2 μmol/L/day during 3 month’s storage. This rate peaked at storage of 120 days (1.87 μmol/L/day) and fell to 0.502 μmol/L/day in the second year of storage. It is concluded that at −20 °C, only 3 weeks of storage time should be considered valid for fairly acceptable stability in MDA values.

Keywords: Malondialdehyde, Storage, Temporal, Oxidative stress

Background

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is one of the most frequently used indicators of lipid peroxidation [1, 2] in biomedical research despite known fluidity of marker due to high lability. During clinical trials this parameter is estimated mostly in stored blood/plasma samples [3]. It is expected and well known that variable period of storage (due to logistics in practical situations) may cause temporal effect on values, however vigorous literature search didn’t find it documented quantitatively ever before.

In a task force ongoing study of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) aiming to estimate oxidative stress with oral iron during pregnancy, this temporal effect in MDA values has been estimated quantitatively [4–6]. The plasma samples were stored at −20 °C with intention to analyze them using Ohkawa method- 1979 [7], as soon as possible. However due to breakdown of spectrophotometer and other logistic problems, the plasma samples from ongoing process of participants in follow-up were stored in the deep freezer at −20 °C temperature for longer than expected. A validity check became imperative after this mishap to see effect of such long storage. Very little information was available on this aspect and also on oxidative stress with oral iron during pregnancy in India [3, 4]. Therefore the quality checks were required for final analysis, in view of its policy implications of the research.

To see whether the varied storage time has been reported causing any change in the levels of MDA, literature was searched in online available sites for published journals—Pub med, Google Scholar; Printed Journals from National Medical Library (NML).

Few reports i.e. Lee [8], Langer et al [9] provided information on effect of storage time on the values of MDA but they used different methods, conditions and duration of storage. Information on time and rate of change was also not there. In practical situations varied gap happens between sample collection and estimation. It usually reported as non-significant [10]. Researcher often reported that “blood sample is withdrawn and after processing the plasma sample was stored until assayed”. This may have ample variation in storage time from time of collection to time of estimations. The similar situation happened with the samples stored for our ongoing study in pregnant women but for more longer and varied period.

Significant temporal effect found on stored samples makes it imperative to report because researchers often use stored sample for MDA estimation. They may become aware of this type of variability with time and temperature and hence finish their task within ideal conditions.

Demographic Profile of Study Participants

All the samples were from women (n = 139) of 20–30 years age, belonging to middle socioeconomic group as per Kupuswamy and coworkers criteria [11] and were normal primigravida without any ailment of acute or chronic aetiology (Normal BMI, blood sugar, hemogram, liver and kidney function tests). All were normaotensive, nondiabetic and ruled out for any illness by ultrasound as well as by clinical examination. Their mental stress status was recorded using standard method [12] and found in normal range.

Method

Primi pregnant women in the beginning of pregnancy were recruited under ICMR Task force study at two tertiary health centers during period of December 2008–2009, to check if there is any change in oxidative stress during oral iron as per national program.

Blood Sampling

Venous blood samples were collected after overnight fasting from median cubital vein of all study participants in heparinized tubes between 08:00 and 09:00 am. All individuals were placed in a reclining position for a minimum of 10 min before blood sampling by the same phlebotomist. Within 30 min of sampling the blood was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min to separate the plasma and immediately stored at −20 °C in capped labeled aliquots with wax tape around them for air tight packing until assayed. The heterogeneity was introduced due to logistics and equipment (spectrophotometer) breakdown hence duration of storage was calculated using subtraction of date of estimation from date of collection.

Method of MDA Estimation

Lipid peroxidation was measured spectrophotometrically as 2-thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS) in blood plasma using the widely cited method of Ohkawa et al. 0.1 mL of plasma samples were mixed with 0.2 mL of 8.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.5 mL of 20 % acetic acid and 1.5 mL of 0.8 % 2-thiobarbituric acid. The reaction mixture was finally made up to 4.0 mL with distilled water. After vortexing, samples were incubated for 1 h in 95 °C and after cooling with tap water; 1.0 mL of distilled water and 5.0 mL of mixture of butanol–pyridine 15:1 (v/v) was added. The mixture was shaken for 10 min. and then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. Butanol–pyridine layer was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm. TBARS values were expressed as MDA equivalents. 1,1, 3,3-tetramethoxypropane (TMP) was used as the standard. Data is shown as μmol/L plasma.

Plasma MDA Ohkawa et al. [7] estimation used following reagents obtained from Sigma Pvt Ltd.,: 8.1 % SDS (0.81 g in 10 mL DW), 20 % acetic acid (pH = 3.5), 0.8 % TBA (0.8 g TBA in 100 mL DW), 15:1 butanol: pyridine (v/v).

Protocol

Results

Values of MDA and trends of mean ± SD values were observed (Table 1) by categorizing into seven groups with 100 days gap in each group. The hyperbolic curve was observed when these values were spread in excel graph sheet (Fig. 1). Parabola of the curve denotes linear rise in initial 100 days of storage and flattening of the curve thereafter, which is depicted by slowing rate of change with time (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

MDA levels with block of 100 days gap from time of collection to time of estimation, n = 139

| Duration of storage (days) | Mean ± SD value of MDA (μmol/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | <100 | 22.72 ± 47.44 |

| 2 | >100–200 | 124.47 ± 97.13 |

| 3 | >200–300 | 238 ± 25 |

| 4 | >300–400 | 250 ± 113.3 |

| 5 | >400–500 | 297 ± 193.9 |

| 6 | >500–600 | 260 ± 10.8 |

| 7 | >600–700 | 276 ± 122 |

Fig. 1.

Temporal effect on MDA levels

The fluctuations (SD) of MDA values were between narrow ranges during first 28 days, while it was increasing with increasing time of storage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

High fluctuation in MDA level starts after 28 days and continues thereafter

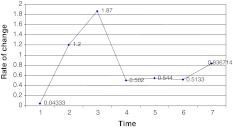

To calculate the rate of changes, weekly blocks were made as shown in Fig. 3. Basis for calculation of rate of change and readings are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Rate of change of MDA values with increasing storage time

Table 2.

Calculation of rate of change in MDA values

| Duration or gap between time of collection and estimation (days) | Mean | Median | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–7 | 28.6 | 22.02 | 13.08 | 51.09 |

| 8–30 | 33.8 | 25.1 | 6.04 | 127.05 |

| 41–91 | 123.7 | 81.04 | 22.1 | 293.1 |

| 100–200 | 327.09 | 333.03 | 71.05 | 624.07 |

| 200–300 | 377.3 | 339.03 | 28.02 | 846.1 |

| 300–400 | 431.7 | 364.1 | 76.1 | 813 |

| 401–708 | 585.7 | 641.1 | 310 | 754 |

It is observed that, till 28 days MDA changes with rate of 0.0433 μmol/L/day but afterward the rate of change is markedly increased to 1.2 μmol/L/day till 90 days and 1.87 μmol/L/day in next 120 days. After 200 days of storage the rate of change slowed down to 0.502 μmol/L/day and remained so for approximately through the 2nd year’s time till 708 days of maximum storage time (Fig. 3).

Discussion

MDA, the organic compound [CH2(CHO)2] was used as marker for oxidative stress [2, 3] in plasma and its concentrations were measured in plasma stored at 4 °C in the presence of various preservative reagents [13]. A rapid rate of formation of MDA (15.0 ± 14.0 nmol/dL/week) was observed in control plasma preserved with diisopropylfluorophosphate and NaN3. Addition of the antioxidant, glutathione or EDTA slowed the rate of change 4.8 ± 3.0 and 4.0 ± 3.0 nmol/dL/week respectively. The combined use of EDTA and glutathione reduced this rate to 1.6 ± 1.6 nmol/dL/week. The use of both glutathione and EDTA provided a fourfold improvement over EDTA alone in protection of the plasma from lipid peroxidation.

In the process of understanding of temperature effect in 1972 the 2 factor hypothesis of Mazur et al. [13] summarised the major forms of damage that result from low temperature. The cold temperature favours the water solute hydrogen bindings [14]. Langer et al. [9] used MDA as an indicator of lipid peroxidation to examine whether oxygen radicals could be an origin of freeze-induced weakness of HES—cryopreserved samples at temperature −196 and stored at −80 °C. Estimation was done at 1, 2, 3 and 6 months of storage period. MDA content increased from 1.5 to 8 μmol/L after 6 months at temperature −80 °C. The MDA levels increased that much (~4 times) with storage time of 3 months at the temperature −20 °C as observed with the ICMR task force study.

It is reported by Langer et al. [9] that membrane fragility is increased after 1 month of storage. We also observed that at same temperature of −20°C and approximately same time (21 days) of storage, there was increased rate of change in MDA values. Our rate of change after 28 days of storage is leaner until 3 month’s storage time (1.2–1.89 units rise/day). After 3 month’s storage the rising rate slowed down to 0.502 units per day till the end of the observation of 708 days. This rising of MDA level and rate of change can be explained by the thesis work of Deepanwita [15]. In his thesis he has mentioned that cold temperature favours the water–solute hydrogen bindings. While the hydrophobic interactions become weaker; the interaction between the amino acids side chain and the polypeptide backbone become disrupted, the protein reach a maximum exposure of polar groups of protein, the protein becomes more unfolded. Deepanwita finds effect of thawing temperature on the values of TABRS and reports highest values at 60° C. His haemoglobin oxidation assay also shows effect of freeze and thawing temperature on outcome values. He has shown abrupt rise in lipid peroxidation in the sample stored at 4 °C in first 12 h and afterwards linear rise till 336 h of observations.

It was concluded by Langer et al. [9] that increased superoxide formation is mediated by freeze induced oxidation at Hb bond Fe. Lee and others [8, 16] studied the antioxidant activity in the plasma for determination of stability with relation to time and temperature of storage. The serum found split in separate portions immediately after blood centrifugation. The samples were kept at −4 °C for 40 h, at room temperature (21–22 °C) for 40 h and at −20 °C for 40 h to 1 month until assayed. They determined the optimum incubation time but found no difference between antioxidant activities in samples of serum kept under all above conditions. But our observations report what happened when storage time is extended beyond 1 month’s time.

Lee [8] showed changing MDA values up till 40 weeks in 7 samples of plasma obtained from blood bank. However they studied the effect on packed samples after opening the samples to air. They found linear increase with time in the initial 10 weeks. They explored effect of time on MDA in plasma which was stored for >1 year but estimated temporal effect only after the samples were thawed. Our estimations are before thawing the samples.

Though the findings observed in our study are due to accidental delay in estimation after storing and for that corrective measures have already been applied in the next phase of recruitments, however it has generated information, not previously published. This has also generated awareness that rate of change of MDA in stored sample should be taken into account while doing estimation and validity check on temporal effect should be undertaken in clinical trials. A large well controlled trial with all established methods to watch the effect of sample storing time at various temperatures can be conducted further to fulfil the gap of information for benefit of the researchers.

Footnotes

The authors listed are for the ICMR Task Force Study.

References

- 1.Caronea D, Loverro G. Lipid peroxidation products and antioxidant enzymes in red blood cells during normal and diabetic pregnancy. Eur J Obster Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993;51:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Requena JR, Fu MX, Ahmed MU, Jenkins AJ, Lyons TJ, Thorpe SR. Lipoxidation products as biomarkers of oxidative damage to proteins during lipid peroxidation reactions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:48–53. doi: 10.1093/ndt/11.supp5.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbonneau MA, Peuchant EC, Clerc M. Free and bound malondialdehyde measured as thiobarbituric acid adduct by HPLC in serum and plasma. Clin Chem. 1991;37:1423–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachili B, Hininger I, Faure H. Increased lipid peroxidation in pregnant women after iron and vitamin C supplementation. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2001;83:103–110. doi: 10.1385/BTER:83:2:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casanueva E, Viteri FE. Iron and oxidative stress in pregnancy. J Nutr. 2003;133:1700S–1708S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1700S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Chandhiok N, Dhillon BS, Kumar P. Role of oxidative stress while controlling iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women—Indian scenario. Indian J of Biochem. 2009;24:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s12291-009-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DM. Malondialdehyde formation in stored plasma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;95:1663–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(80)80090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer R, Herold T, Henrich HA. Lipid peroxidation and hemolysis in HES cryopreserved erythrocytes (abstract) Beitr Infusionsther Transfusionsmed. 1996;33:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu MT, Lua A, Toke A, Uysa M. Imbalance between lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in preeclampsia. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:37–40. doi: 10.1159/000009994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar N, Shekhar C, Kumar P, Kundu AS. Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale—updating for 2007. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:1131–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck TA, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Sychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazur P, Leibo SP, Chu EHY. A two-factor hypothesis of freezing injury: evidence from Chinese hamster tissue-culture cells. Exp Cell Res. 1972;71:345–355. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franks F, Hatley R, Friedman HM. The thermodynamics of protein stability: cold destabilization as a general phenomenon. Biophys Chem. 1988;31:307–315. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(88)80037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deepanwita D. Red blood cell stabilization: effect of hydroxyethyl starch on RBC viability, functionality and oxidative State during different freeze thaw conditions [MAppSci thesis]. India, Rourkela: National Institute of Technology; 2009, 60–61.

- 16.Wade CR, Ru AM. Plasma thiobarbituric acid reactivity reaction conditions and the role of iron, antioxidant and lipidperoxyradicals on the quantification of plasma lipid peroxidation. Life Sci. 1988;43:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lykkesfeldtl J, Viscovich M, Poulsen HE. Plasma malondialdehyde is induced by smoking: a study with balanced antioxidant profiles. Brit J Nutr. 2004;92:203–206. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]