Abstract

We report the shotgun proteomic analysis of mammalian cell lysates that contain low nanogram amounts of protein. Proteins were denatured using methanol, digested using immobilized trypsin, and analyzed by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. The approach generated more peptides and higher sequence coverage for a mixture of three standard proteins than the use of free trypsin solution digestion of heat- or urea-denatured proteins. We prepared triplicate RAW 264.7 cell lysates that contained 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng, and 300 ng of protein. An average of 2 ± 1, 23 ± 2, 134 ± 11, and 218 ± 26 proteins were detected for each sample size, respectively. The numbers of both protein and peptide IDs scaled linearly with the amount of sample taken for analysis. Our approach also outperformed traditional methods (free trypsin digestion of heat- or urea-denatured proteins) for 6 ng to 300 ng RAW 264.7 cell protein analysis in terms of number of peptides and proteins identified. The use of accurate mass and time (AMT) tags resulted in the identification of an additional 16 proteins based on 20 peptides from the 6 ng cell lysate prepared with our approach. When AMT analysis was performed for the 6 ng cell lysate prepared with traditional methods, no reasonable peptide signal could be obtained. In all cases, roughly ~30% of the digested sample was taken for analysis, corresponding to the analysis of a 2 ng aliquot of homogenate from the 6 ng cell lysate.

Introduction

Shotgun proteomics routinely identifies more than 10,000 proteins from mammalian cell lysates [1]. Achieving this great depth of coverage requires relatively large amounts of sample, typically from hundreds of micrograms to several milligrams. There are cases where the amount of sample is quite limited, such as circulating tumor cells [2] and cells isolated using laser-capture microdissection, where only nanograms of sample are available. Proteomic analysis for these samples is quite difficult and highly efficient separation and sensitive detection is necessary. A high efficiency sample preparation method is also critically important.

For high efficient separation and sensitive detection system, Shen et al. [3, 4] coupled a highly efficient (peak capacities of ~103) 15 µm i.d. packed capillary column to Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer for characterizing proteins from nanogram range of complex proteomic samples. Ultrahigh sensitivity (<75 zmol for individual proteins) was obtained, and a 2.5 ng sample provided 14% coverage of all annotated open reading frames for the microorganism Deinococcus radiodurans with the system. Waanders et al. [5] developed a high sensitivity chromatographic system for measurement of nanogram complex samples with very high resolution. The system was based on splitting gradient effluents into a capture capillary and provided an inherent technical replicate. More than 2,400 proteins could be identified from kidney glomeruli isolated by laser capture microdissection in a single analysis. Quantitative comparison of the proteome of single islets, containing 2,000–4,000 cells, treated with high or low glucose levels, was also performed with the system, and most of the characteristic functions of beta cells were covered.

For high efficient sample preparation method, several research groups have recently reported preparation methods for samples generated from as few as 500 cells. For example, Li’s group developed a sample preparation method involving the surfactant NP-40 for cell lysis, followed by acetone precipitation of the proteins and trypsin digestion in NH4HCO3 buffer for shotgun proteomic analysis of 500 to 5,000 MCF-7 cells [6]. These cells are ~20-µm in diameter and ~500 pg of protein was extracted per cell. Li’s group identified 167 proteins from an MCF-7 cell homogenate prepared from 500 cells (250 ng); the number of proteins IDs decreased dramatically to ~50 proteins from 250 cells (125 ng). Figeys’ group developed a fully integrated sample processing and analysis platform for proteomic analysis of human embryonic stem cells [7]. They first loaded a cell lysate onto a capillary column with a strong cation exchange (SCX) monolith matrix to trap proteins, followed by on-column reduction, alkylation, and trypsin digestion. They then connected the SCX column to a reversed phase capillary column for automated two-dimensional LC-MS/MS protein identification and quantitation. They report the identification of 68 proteins from 500 cells with the system. These cells appear to be smaller than the MCF-7 cells used by Li’s group, and the protein content of the cell lysate was likely on the order of 100 ng. Mann’s group developed a filter-aided sample preparation method for proteome analysis [8]. They first lysed cells with a 4% SDS buffer solution, and captured and concentrated the proteins into microliter volumes in an ultrafiltration device. They then used the ultrafiltration device as a “proteomic reactor” for detergent removal, buffer exchange, chemical modification, and protein digestion. They then eluted the digest from the device through centrifugation and performed single run LC-MS/MS analysis to identify ~1,700 proteins from a lysate corresponding to 1,500 HeLa cells [9]. The protein content of 1,500 HeLa cells was between 0.3 to 0.75 µg (200 to 500 pg each cell).

In the three sample preparation methods mentioned above, free trypsin was used for protein digestion, which required at least several hours. Although sequencing-grade modified trypsin has been specially engineered to minimize auto-digestion [10], autodigestion products nevertheless can be identified. In order to reduce contamination by auto-digestion products, a limited amount of trypsin was usually used for free trypsin digestion, which affected the digestion efficiency, especially for nanogram level or lower amount of complex sample digestion. The three protocols mentioned above performed efficient preparation for high-nanogram amounts of cellular protein homogenate, but several steps can be further improved for proteome analysis of low nanogram protein samples.

Immobilized trypsin has been widely used for protein profiling [11–18], and is more efficient than free trypsin for digestion of very low concentration of proteins [11, 12], presumably due to higher enzyme-to-substrate ratio and reduced trypsin auto-digestion [13, 14]. For protein denaturation, organic solvents, such as methanol, can unfold the protein structure [19, 20], and are widely used to assist trypsin digestion of proteins [21–23]. In this work, we report a bottom-up protein analysis method that employs methanol-based protein denaturation and immobilized trypsin for analysis of low nanogram amounts of a RAW 264.7 cell lysate. Accurate mass and time (AMT) tag [24] was also used to increase the number of protein identifications. We demonstrate that ~20 proteins could be identified by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS from a 2 ng aliquot of a sample prepared from a 6 ng cell lysate. We also compared the performance of our approach and traditional methods (free trypsin digestion of heat- or urea-denatured proteins) for analysis of 6–300 ng RAW 264.7 cell lysate.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Bovine pancreas TPCK-treated trypsin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), bovine heart cytochrome c, equine myoglobin, ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3), dithiothreitol (DTT) and iodoacetamide (IAA) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetonitrile (ACN) and formic acid (FA) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Methanol was purchased from Honeywell Burdick & Jackson (Wicklow, IE, USA). Water was deionized by a Nano Pure system from Thermo Scientific (Marietta, OH, USA).

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) with L-glutamine and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Mammalian Cell-PE LB™ Buffer used for cell lysis was purchased from G-Biosciences (St. Louis, MO, USA). Complete, mini protease inhibitor cocktail (provided in EASYpacks) was purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Immobilized trypsin preparation

Immobilized trypsin was prepared as described previously [12]. Carboxyl functionalized magnetic beads were activated with N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide sodium salt and N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride, followed by trypsin immobilization through reaction between the amine groups of trypsin and the succinimide groups of the particles.

Low nanogram range standard proteins and RAW 264.7 cell lysate preparation

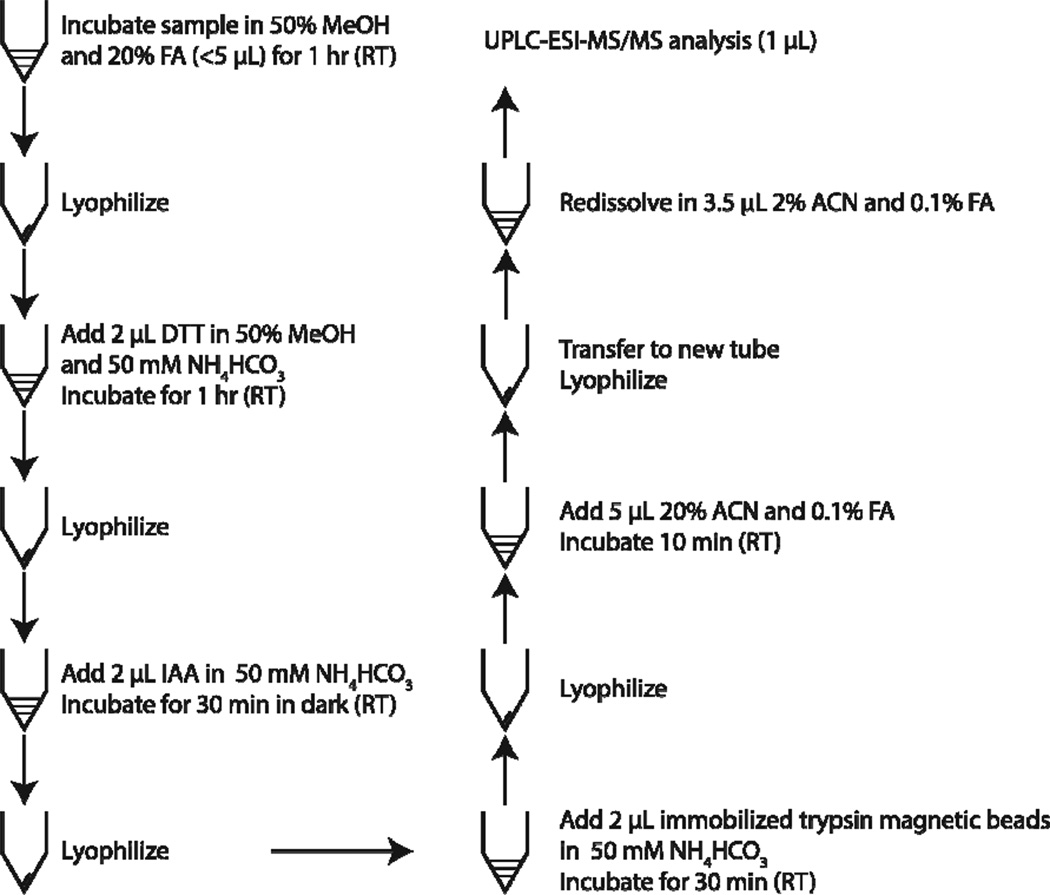

The sample preparation procedure is shown in Figure 1. For standard proteins, a three-standard-protein mixture (3.3 ng BSA, 3.3 ng cytochrome c, and 3.3 ng myoglobin) was dissolved in 5 µL of 50% methanol and 20% FA solution, and kept at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was next lyophilized. An aliquot of 2 µL of 1 mM DTT dissolved in 50% methanol and 50 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) was added and kept at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was then lyophilized again. An aliquot of 2 µL of 2.5 mM IAA dissolved in 50 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After lyophilization, 20 µg of immobilized trypsin beads suspended in 2 µL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5) was added for protein digestion at room temperature for 10 min. After digestion, the solution was lyophilized again. An aliquot of 5 µL of 20% ACN and 0.1% FA was added, followed by several rounds of aspiration and dispension. After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the digests were collected in a new Eppendorf tube and lyophilized, followed by redissolution in 5.5 µL 2% ACN and 0.1%FA solution for UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis in triplicate.

Figure 1.

Procedure for protein sample preparation with methanol denaturation and digestion using immobilized trypsin. All steps are performed in 200 µL Eppendorf microcentrifuge tubes.

For preparation of the RAW 264.7 cell lysate, cells were first washed 3 times with PBS to remove culture medium. The cells were then lysed with 1 mL mammalian Cell-PE LB™ buffer and complete protease inhibitor solution for 30 min on ice. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 18,000 g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected, followed by protein concentration measurement with bicinchoninic acid (BCA). A 300 µL cell lysate aliquot was precipitated with 1.2 mL cold acetone for 24 h at −20 °C. After centrifugation, the protein pellet was washed again with cold acetone. The protein pellet was dried at room temperature and then dissolved in 100 µL 50% methanol and 20%FA solution at a protein concentration of ~0.6 mg/mL. Three aliquots each containing 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng, and 300 ng of protein with volume less than 5 µL were put into 200 µL Eppendorf tubes. The 12 samples were treated with a procedure similar to the standard proteins preparation with the following changes. First, for 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng and 300 ng proteins, 2 µL of 1 mM, 5 mM, 20 mM and 50 mM DTT was used for reduction, and 2 µL of 2.5 mM, 12 mM, 50 mM, and 125 mM IAA was used for alkylation, respectively. Second, 40 µg immobilized trypsin beads were used for RAW 264.7 cell lysate digestion for 30 min. Third, the digests were dissolved in 3.5 µL 2% ACN and 0.1% FA solution for UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

Details about the traditional sample preparation methods (free trypsin digestion of heat- or urea-denatured proteins) for standard proteins and RAW 264.7 cell lysate preparation are illustrated in supporting material I.

UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis

A nanoACQUITY UltraPerformance LC® (UPLC®) system (Waters) was used for separation of the protein digests. Buffer A (0.1% FA in water) and buffer B (0.1% FA in ACN) were used as mobile phases for gradient separation. Protein digests were automatically loaded onto a commercial C18 reversed phase column (100 µm×100 mm, 1.7 µm particle, BEH130C18, column temperature 40 °) with 1% buffer B for 5 min at a flow rate of 1.2 µL/min, followed by gradient separation. For standard protein digests analysis, the gradient was 15 min from 1% B to 85% B, and maintained at 85% B for 5 min. For RAW 264.7 cell lysate digests analysis, the gradient was 5 min from 1% B to 10% B, 30 min to 40% B, 2 min to 85% B, and maintained for 8 min. The column was equilibrated for 14 min with 1% buffer B prior to the next sample analysis. The eluted peptides from the C18 column were pumped through a manually pulled capillary tip for electrospray, and analyzed by an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The electrospray voltage was 1.8 kV, and the ion transfer tube temperature was 300 °. The mass spectrometer was programmed in a data dependent mode. Full MS scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer over 395–1900 m/z range with resolution of 60,000. Ten most intense peaks (for standard protein digests analysis) and 20 most intense peaks (for cell lysate digests analysis) with charge state ≥ 2 were selected for sequencing and fragmented in the ion trap with normalized collision energy of 35%, activation q = 0.25, activation time of 10 ms, and one microscan. For all sequencing events, dynamic exclusion was enabled. For standard protein digest analysis, peaks selected for fragmentation more than once within 45 s were excluded from selection for 45 s. For cell lysate digests analysis, peaks selected for fragmentation more than once within 15 s were excluded from selection for 15 s. For each run, 1 µL digest was injected for analysis.

Data analysis

Database searching of raw files was performed in Proteome Discoverer 1.3. SEQUEST was used for standard proteins database searching against ipi.bovin.v3.68.fasta (for BSA and cytochrome c) and equine.fasta (for myoglobin). MASCOT 2.2.4 was applied for RAW 264.7 cell lysate database searching against SwissProt database with taxonomy as mouse (16,252 sequences). Database searching against the corresponding decoy database was also performed to evaluate the false discovery rate (FDR) of peptide identification. The database searching parameters included up to two missed cleavages allowed for full tryptic digestion, precursor mass tolerance 50 ppm (for standard protein digests) and 10 ppm (for cell lysate digests), fragment mass tolerance 1.0 Da (for standard protein digests) and 0.5 Da (for cell lysate digests), cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification, oxidation of methionine as variable modification. For cell lysate digests, deamidated (NQ) was also set as variable modification for database searching. In order to analyze the trypsin auto-digestion from cell lysate data, MASCOT database searching against ipi.bovin.v3.68.fasta was also performed with fragment mass tolerance 1.0 Da, and other parameters were same as that used for RAW 264.7 cell protein analysis mentioned above.

For standard proteins and trypsin auto-digestion analysis, peptides identified with confidence value as high were considered as positive hits. Because of the small data set generated from 6 ng and 30 ng cell lysate sample, accurate evaluation of FDR is difficult. The accuracy of commonly used target-decoy search strategy is diminished greatly with very small data set [25]. In order to make the protein and peptide lists confident from 6 ng and 30 ng samples, we referred to reference [6], in which 95% confidence and manual evaluation were applied for filtration of peptide identifications. In our work, a stricter filtration, 97% confidence (mascot significance threshold 0.03) and manual evaluation were used to filter the results from 6 ng and 30 ng cell lysate samples. For the results from 120 ng and 300 ng cell lysate samples, we adjusted the mascot significance threshold (≤ 0.01, 99% confidence or higher) to make the FDR of peptide identification less than 1%. On Protein level, minimum number of peptide 1 for each protein, count only rank 1 peptides, and count peptide only in Top scored proteins were applied for all data filtration. In addition, protein grouping was enabled, and strict maximum parsimony principle was applied. The number of proteins reported in the manuscript was the protein group number. Finally, the protein groups identified from 6 ng and 30 ng cell lysate samples but not included in 300 ng cell lysate protein lists were removed manually unless confidence value of corresponding peptides was high. The contaminant proteins including keratins and serum albumin were removed from the protein lists.

Results and discussion

Immobilized trypsin and methanol based method

In this work, trace protein samples were denatured with methanol and digested using immobilized trypsin for shotgun based proteomic analysis of cell lysates, Figure 1. All the steps were performed in 200 µL Eppendorf tubes. Lyophilized proteins were dissolved in 50% (v/v) methanol and 20% (v/v) FA (< 5 µL). FA was used for efficient dissolution of proteins, and methanol for denaturation of proteins [19, 20]. After lyophilization, the proteins were reduced with DTT and alkylated with IAA. For reduction, 50% methanol was added to the solution to assist reduction of the disulfide bonds, and the reaction was performed at room temperature to keep the solution at the bottom of the tube. After reduction and alkylation, immobilized trypsin was used for protein digestion due to its superior performance for low protein concentration samples compared with free trypsin [11, 12].

For analysis of nanogram amounts of standard proteins, samples were digested with 20 µg of immobilized trypsin beads for 10 min at room temperature; 1.5 µg trypsin was used for digestion, corresponding to a concentration of 0.75 mg/mL. For analysis of nanogram amounts of cell lysate, samples were digested with 40 µg of immobilized trypsin beads for 30 min at room temperature; 3.0 µg of immobilized trypsin was used for digestion, corresponding to a concentration of 1.5 mg/mL. This high trypsin concentration produced an efficient digestion of the trace proteins, and the use of immobilized trypsin reduced auto-digestion. After digestion, 20% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% FA were used to dissolve the lyophilized peptides and reduce the hydrophobic interaction between peptides and immobilized trypsin beads to improve peptide recovery.

To check for trypsin auto-digestion, we performed MASCOT database searching against the bovine database for the cell lysate data from our approach and traditional methods, S-Figure 1 in supporting material I. The number of peptides, the spectral counts, and the peptide intensity of trypsin obtained with traditional methods dramatically increased when cell lysate amount was increased from 6 ng to 300 ng, and the corresponding amount of free trypsin used for protein digestion increased from 0.3 ng to 15 ng. For our approach, when cell lysate amount was increased from 6 ng to 300 ng, the number of peptides and spectral counts of trypsin were decreased from 4 ± 1 to1 ±1 and from 13 ± 7 to 1 ± 1, respectively. However, the peptide intensity of trypsin was reasonably stable through 6 ng to 300 ng cell lysate sample prepared with our approach. These results were not unexpected. For traditional methods, when the cell lysate amount increased, free trypsin amount used for digestion increased from 0.3 ng to 15 ng, leading to more trypsin peptides, higher spectral counts, and higher peptide intensity. However for our approach, a constant amount of immobilized trypsin (~3 µg) was used for 6 ng to 300 ng cell lysate preparation, so the peptide intensity of trypsin should be similar. For number of peptides and spectral count of trypsin, when the cell lysate amount increased from 6 ng to 300 ng, the concentration of cell lysate digests dramatically increased, and this affected the peptide identification of trypsin, leading to lower number of peptides and protein spectral count. Interestingly, the number of peptides, spectral count, and peptide intensity of trypsin obtained with our approach from 6 ng cell lysate sample were comparable with that obtained with traditional methods from 300 ng cell lysate sample, which indicated that comparable trypsin auto-digestion was obtained. It is worth mentioning that the trypsin concentration used in our approach is about 700 times higher than that used in traditional methods for 300 ng cell lysate preparation (~1.5 mg/mL vs. ~0.002 mg/mL), which indicated that the use of immobilized trypsin reduced auto-digestion. Because with our approach only about 4 peptides of trypsin could be identified and their peak width was only ~20-s, their interference for cell lysate analysis was negligible.

There are two main advantages of this method. First, sample cleanup is eliminated because neither urea nor detergent was used for dissolution and denaturation of proteins. Second, the use of immobilized trypsin at ~1 mg/mL concentration produced efficient trace protein digestion with negligible trypsin auto-digestion.

Analysis of nanogram amounts of standard proteins

We applied our protocol to analyze nanogram amounts of standard proteins, and compared this protocol with two traditional methods: urea or heat denaturation plus free trypsin digestion. A three-standard-protein mixture (BSA, cytochrome c and myoglobin) with 3.3 ng of each protein was used as the sample. After analysis with UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system in triplicate, on average 6, 2 and 1 peptides were identified with our protocol for BSA, cytochrome c and myoglobin, respectively, Table 1. Only 4 and 3 peptides were identified with traditional methods for BSA, and no peptides were identified for cytochrome c and myoglobin. These results suggest that this immobilized trypsin and methanol-based protocol generates more peptides, higher sequence coverage, and higher spectral counts for trace protein preparation compared with traditional methods.

Table 1.

Identification results of a three-protein mixture with three different sample preparation protocols followed by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis in triplicate*

| Identifications (Number of peptides/sequence coverage/protein spectral count) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.3 ng BSA | 3.3 ng cytochrome c | 3.3 ng myoglobin | |

| Methanol + immobilized trypsin | 6/12%/9 | 2/14%/2 | 1/8%/1 |

| heat + free trypsin | 4/10%/5 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| Urea + free trypsin | 3/7%/3 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

Number of peptides, sequence coverage and protein spectral count are the means from triplicate analysis.

The enhanced performance may be due to two reasons. First, in our protocol all operations were performed at room temperature and the sample was kept at the bottom of the Eppendorf tube, which reduces the adsorption of sample on the inner wall of the tube. In addition, no sample cleanup steps were performed, which also reduces sample loss. Second, immobilized trypsin was used for protein digestion in our protocol. Its trypsin concentration was about three orders of magnitude higher than traditional free trypsin digestion, which results in more efficient digestion for trace proteins [11, 12].

In order to better understand the results from our protocol and traditional methods, we investigated the intensity of four peptides (two peptides from BSA, one from cytochrome c and one from myoglobin) from the three-standard-protein-mixture data obtained with our protocol and traditional methods, S-Table 1 in supporting material I. This study was performed by manual extraction with Xcalibur software (mass tolerance 10 ppm). For the BSA peptide identified with all protocols, the intensity from our protocol is about 2 and 4 times higher than that from heat plus free trypsin and urea plus free trypsin protocol, respectively. For peptides only identified with our protocol, the intensity from our protocol is dramatically higher than that from traditional methods. These results indicate that our protocol can yield higher peptide recovery leading to higher peptide intensity and more identification that conventional approaches.

Application for analysis of low nanogram aliquots of RAW 264.7 cell lysate

To evaluate the methanol/immobilized trypsin protocol for trace analysis of a complex sample, a RAW 264.7 cell lysate with 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng, and 300 ng of protein were used as samples. In order to evaluate the reproducibility of the sample preparation process, each sample was prepared in triplicate. Traditional methods were also used for triplicate preparation of 6 ng to 300 ng cell lysate, and comparison between our protocol and traditional methods was performed.

For 6 ng RAW 264.7 cell lysate, 2 ± 1 proteins were identified with at least one unique peptide per protein from triplicate sample preparation with our protocol. The number of peptide and protein IDs increased linearly with the sample size, Table 2 (r = 0.981 for peptides and 0.972 for proteins). No proteins could be obtained from 6 and 30 ng RAW 264.7 cell lysate with traditional methods. The results indicated that our protocol outperformed traditional methods for low nanogram RAW 264.7 cell lysate analysis. The identified peptides and proteins from the three different protocols are listed in supporting material II.

Table 2.

Protein and peptide IDs for different size samples from three different sample preparation protocols

| Protein content of lysate |

Protein IDs/Peptide IDs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol + immobilized trypsin |

heat + free trypsin | Urea + free trypsin | |

| 6 ng | 2 ± 1/2 ± 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 ng | 23 ± 2/29 ± 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 120 ng | 134 ± 11/213 ± 19 | 7±2/8±2 | 0 |

| 300 ng | 218 ± 26/376 ± 59 | 50 ±8/69±15 | 8±1/9±2 |

The reproducibility of sample preparation with our protocol was investigated. Relative standard deviations of the number of peptides and proteins identifications from triplicate preparation were around 10% (except 6 ng cell lysate), which demonstrates good reproducibility for nanogram range cell lysate preparation.

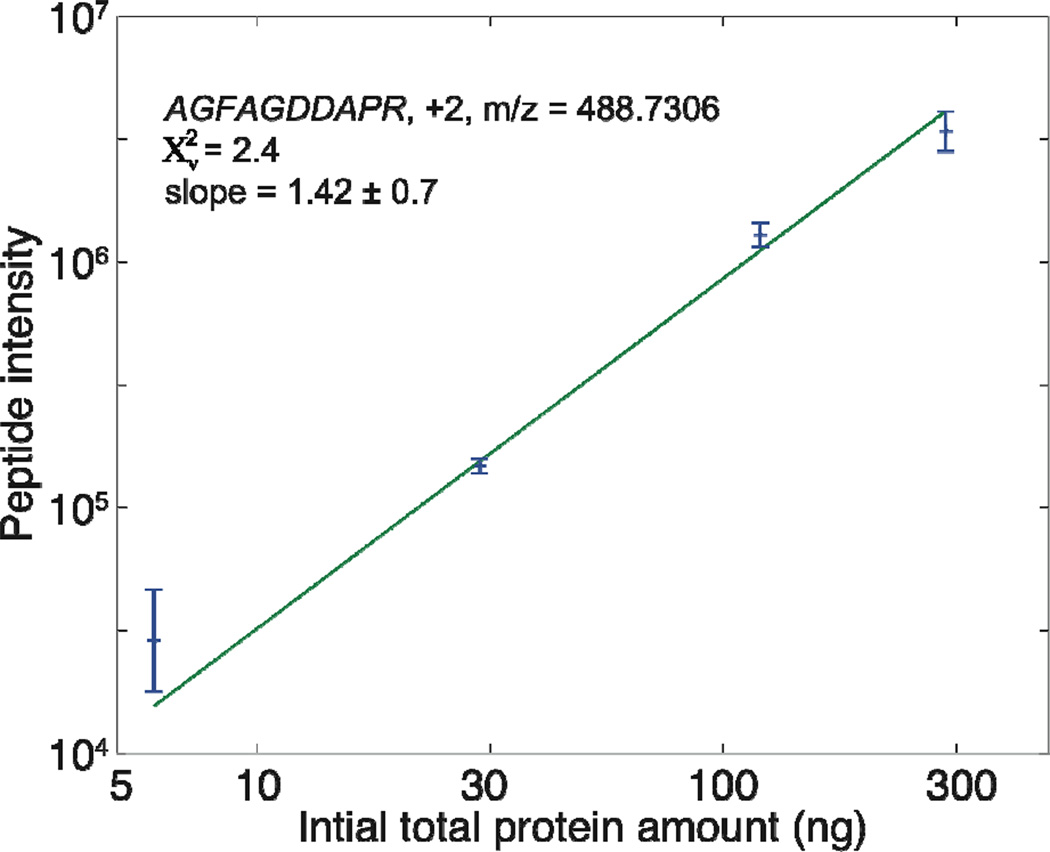

In addition, peptide intensity was also used to evaluate our protocol. One actin peptide, AGFAGDDAPR (charge +2, m/z 488.7306), was chosen for analysis. Outstanding linearity between initial sample amount from 6 ng to 300 ng and peptide intensity was obtained (R2 =0.999), Figure 2. The RSD of the peptide intensity from triplicate sample preparations of 30 ng to 300 ng RAW 264.7 cell lysate was less than 20%. Reproducibility degraded to 48% for 6 ng cell lysate. Our protocol appears to be useful for trace protein quantitation.

Figure 2.

Log-log plot of peak intensity vs. initial sample amount for the peptide AGFAGDDAPR, after analysis by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Error bars are calculated based on propagation of errors based on the standard deviation of the mean. Line is the result of a weighted least squares fit to a line.

The quality of identification is critically important. However, because of the small dataset generated from 6 ng and 30 ng samples, it is difficult to use the traditional FDR approach to evaluate the quality of identification. Here, we used the Mascot significance threshold 0.03 (97% confidence) and manual evaluation to filter the identifications for 6 ng and 30 ng samples. Filtrations on protein level were also performed for 6 ng and 30 ng samples, including minimum number of peptide 1 for each protein, count only rank 1 peptides and count peptide only in top scored proteins. Protein grouping was also enabled, and strict maximum parsimony principle was applied. We acquired the MS1 spectrum using the Orbitrap mass analyzer so that the mass error for the parent ions was controlled to less than 10 ppm. We also controlled the mass error of the fragment ions less than 0.5 Da for database searching. These settings are helpful for confident tandem spectra identifications. The annotated tandem spectra for identified peptides from 6 ng and 30 ng samples with our protocol are presented in supporting material III.

Accurate mass and time tag analysis

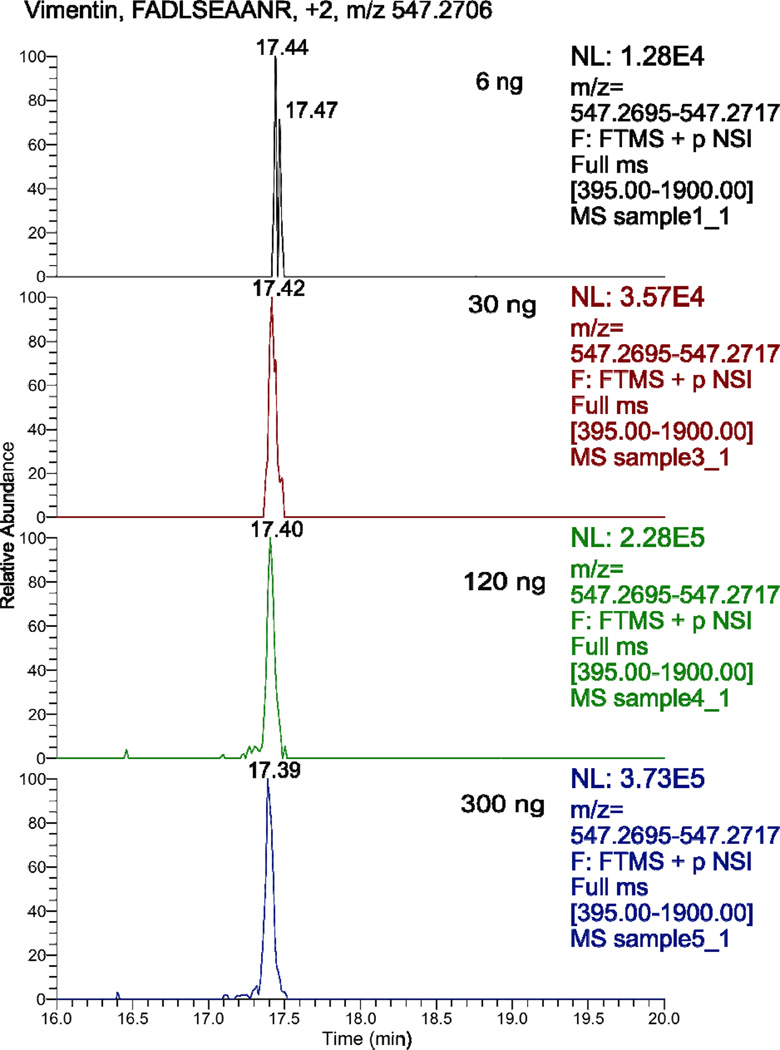

Accurate mass and time (AMT) tag of peptides is useful for improving the dynamic range of identifications [24]. Here, we used AMT tag to increase the number of identified proteins for the 6 ng cell lysate samples from our protocol. In this procedure, we chose 20 unique peptides corresponding to 16 relatively high abundant proteins, S-Table 2 in supporting material I. These peptides were confidently identified from 120 ng or 300 ng cell lysate samples prepared with our protocol with Exp Value less than 0.001, and most of them were also identified in the 30 ng cell lysate sample. In addition, these peptides generated a consistent signal and retention time for triplicate preparations of 300 ng cell lysate with our protocol, supporting material IV.

We extracted these peptides manually with Xcalibur software with mass tolerance as 2 ppm from .raw files of 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng and 300 ng cell lysates prepared with our protocol, supporting material V. Figure 3 presents an example of the data. All 20 peptides were of reasonable signal and consistent retention time (less than 10 s difference compared with the 300 ng cell lysate data) in the .raw files. We also evaluated the relationship between the sample amount and intensity of those 20 peptides, S-Figure 2 in supporting material I. Our results showed that when the sample amount increased from 6 ng to 300 ng, the intensity of all peptides reasonably increased and most of them increased linearly. The highly consistent retention time and mass in addition to the linear relationship between sample amount and peptide intensity of these peptides in the .raw files demonstrate that the 20 peptides corresponding to 16 proteins can be confidently detected even with only 6 ng initial protein amount. Therefore, a total of about 20 proteins and more than 20 peptides can be identified through combination of tandem MS and AMT tag analysis from 6 ng initial cell lysate prepared with our protocol. We also applied the AMT tag method for the data of 6 ng cell lysate samples prepared with traditional methods; no useful signal was obtained.

Figure 3.

Extracted spectra of the peptide FADLSEAANR, from raw files of 6 ng, 30 ng, 120 ng and 300 ng cell lysates with Xcalibur software with mass tolerance as 2 ppm.

Conclusion

The smallest sample used in this paper, 6 ng, corresponds to the protein content of only ~60 RAW 264.7 cells, assuming 0.1 ng protein per cell [26]. Only ~30% of the digest was used for UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis, so that sample analysis from ~20 cells would be possible by loading the entire digest.

Roughly an order of magnitude improvement is required for single cell bottom-up protein identification and quantitation using mass spectrometry, which will require addressing two issues. First, sample manipulations must be improved. This group has developed a suite of tools for the characterization, selection, injection, and lysis of single cells in a fused silica capillary, followed by on-column labeling, one- or two-dimensional capillary electrophoresis separation, and ultrasensitive laser-induced fluorescence detection [27–29]. We have also demonstrated the on-column digestion of proteins followed by capillary electrophoresis and electrospray ionization MS/MS analysis [17, 30]. Combination of these technologies should be straightforward.

Second, the instrument sensitivity must be improved. Narrower columns should provide enhanced mass sensitivity. Li, Figeys, and Mann employed 50-µm or 75-µm ID separation columns. We recently reported the use of capillary zone electrophoresis-ESI-MS/MS for the analysis of a 700 pg aliquot of a RAW 264.7 cell lysate digest; six proteins were identified [31]. The use of multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) should also provide enhanced sensitivity. For example, we recently described the use of MRM for analysis of a standard peptide in a fairly complex matrix; high zeptomole detection limits with nearly four order of magnitude dynamic range were achieved using a 50-µm ID capillary [32].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. William Boggess in the Notre Dame Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility for his help with this project. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM096767).

References

- 1.Geiger T, Wehner A, Schaab C, Cox J, Mann M. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Ryan P, Balis UJ, Tompkins RG, Haber DA, Toner M. Nature. 2007;450:1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen Y, Tolić N, Masselon C, Paša-Tolić L, Camp DG, II, Hixson KK, Zhao R, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:144–154. doi: 10.1021/ac030096q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen Y, Tolić N, Masselon C, Paša-Tolić L, Camp DG, II, Lipton MS, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004;378:1037–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waanders LF, Chwalek K, Monetti M, Kumar C, Lammert E, Mann M. PNAS. 2009;106:18902–18907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908351106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang N, Xu M, Wang P, Li L. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:2262–2271. doi: 10.1021/ac9023022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian R, Wang S, Elisma F, Li L, Zhou H, Wang L, Figeys D. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiśniewski JR, Ostasiewicz P, Mann M. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:3040–3049. doi: 10.1021/pr200019m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice RH, Means GE, Brown WD. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1977;492:316–321. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J, Liang Z, Qiao X, Deng Q, Tao D, Zhang L, Zhang Y. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:2949–2956. doi: 10.1021/ac702343a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L, Li Y, Yang P, Zhu G, Dovichi NJ. J. Chromatogr. A. 2012;1220:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Zhang L, Liang Z, Shan Y, Zhang Y. Trends Anal. Chem. 2011;30:691–702. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan J, Sun L, Liang Z, Zhang J, Wang H, Zhang L, Zhang W, Zhang Y. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1106:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Xu X, Yan B, Deng C, Yu W, Yang P, Zhang X. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:2367–2375. doi: 10.1021/pr060558r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L, Ma J, Qiao X, Liang Y, Zhu G, Shan Y, Liang Z, Zhang L, Zhang Y. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:2574–2579. doi: 10.1021/ac902835p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Wojcik R, Dovichi NJ. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:2007–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye M, Hu S, Schoenherr RM, Dovichi NJ. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:1319–1326. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonso DOV, Daggett V. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:501–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griebenow K, Klibanov AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11695–11700. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell WK, Park ZY, Russell DH. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:2682–2685. doi: 10.1021/ac001332p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slysz GW, Schriemer DC. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strader MB, Tabb DL, Hervey WJ, Pan C, Hurst GB. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:125–134. doi: 10.1021/ac051348l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RD, Anderson GA, Lipton MS, Pasa-Tolic L, Shen Y, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Udseth HR. Proteomics. 2002;2:513–523. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200205)2:5<513::AID-PROT513>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Nat. methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen D, Dickerson JA, Whitmore CD, Turner EH, Palcic MM, Hindsgaul O, Dovichi NJ. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. (Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, Krylov S, Arriaga EA, Polakowski R, Dovichi NJ. Anal Chem. 2000;72:318–322. doi: 10.1021/ac990694y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu S, Le Z, Krylov S, Dovichi NJ. Anal Chem. 2003;75:3495–3501. doi: 10.1021/ac034153r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dovichi NJ, Hu S. Chemical cytometry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Bio. 2003;7:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoenherr RM, Ye M, Vannatta M, Dovichi NJ. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2230–2238. doi: 10.1021/ac061638h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun LL, Zhu G, Li Y, Wojcik R, Yang P, Dovichi NJ. Proteomic [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Wojcik R, Dovichi NJ, Champion MM. Anal Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1021/ac300926h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.