Abstract

Colorectal cancer is the second most common malignancy among men and women in the United States, and the 5-year survival rate remains poor despite recent advances in chemotherapy and targeted agents. The mainstay of therapy for advanced disease remains the cytotoxic chemotherapy including 5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin. The USFDA approval and introduction of targeted therapies, including cetuximab and panitumumab (monoclonal antibodies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)) and bevacizumab (monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular epithelial growth factor (VEGF)), has improved the median survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to around 24 months. Clearly, better and more efficacious drugs are needed, and target-specific agents remain the future of cancer treatment. On this front, rapid advances are being made, which are likely to change the future of the management of metastatic colorectal cancer. However, absence of specific biomarkers for the use of targeted agents, in the subset of population who will benefit from the treatment, remains a major drawback. In this paper, we review agents that are in phases 1 and 2 clinical development, specifically targeting the EGFR and its subsequent downstream pathways.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2011 around 141,210 Americans were diagnosed with CRC of which 49,380 succumbed from the disease [1]. Over the past several decades, the incidence and mortality of CRC have declined. The treatment for colorectal cancer has transitioned from single agent chemotherapy to combination cytotoxic therapies and target-specific agents. Fluoropyrimidines, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin are the main drugs for cytotoxic chemotherapy. The standard of treatment for metastatic CRC (mCRC) is FOLFOX (5 fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) or FOLFORI (5 fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan). Bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab are the target-specific agents approved by FDA for the treatment of colorectal cancer [2, 3]. The present combination of cytotoxic chemotherapies and the addition of target-specific agents have increased the overall survival of metastatic colon cancer to around 24 months [4–7].

2. EGFR Signaling Pathway

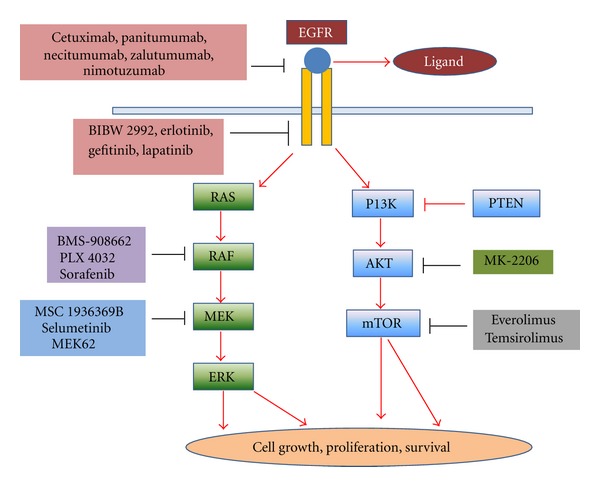

Human tumors are rich in growth factors and their receptors. Among the mostly widely studied is the EGF receptor family [8, 9]. The EGFR gets activated after a ligand binding, which in turn activates 2 pathways, the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and the PI3-AKT-mTOR pathway. Drugs which act on this receptor can be classified into 3 subcategories (Figure 1):

drugs that inhibit the extracellular domain,

drugs inhibiting RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway,

drugs inhibiting PI3-AKT-mTOR pathway.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing various drugs acting on EGFR and its subsequent pathways. MEK: MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) kinases/extracellular-signal-regulated kinases, ERK: extracellular-signal-related kinase; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog, mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin.

Cetuximab (an IgG1 monoclonal antibody) and panitumumab (fully human IgG2 monoclonal antibody) are the only monoclonal antibodies against EGFR that are approved for treatment of metastatic CRC. Only small subsets of patients show clinical benefit to cetuximab and panitumumab. Patients who have KRAS mutation are resistant to cetuximab [6]. Mutations of KRAS lead to activation of RAS-RAF-MEK pathway which renders an inhibition in the receptor further upstream fairly ineffective. Recently BRAF mutation and loss of PTEN were also attributed to resistance to cetuximab and panitumumab therapy [10–12]. KRAS mutations are seen in 40–50% of CRC, while BRAF mutations are seen in 10% of colorectal cancer. The best response to cetuximab and panitumumab appears to be in patients who have a combination of wild-type KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA and express the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) protein [12–14]. PTEN is a tumor suppressor protein that inhibits the PI3/AKT pathway, and loss of this protein will activate this pathway leading to tumor progression.

3. Novel Drugs in Phase 2 Clinical Development

3.1. Inhibitors of EGFR/Drugs Acting on Extracellular Ligand Binding Domain

(1) BIBW 2992/Afatinib —

Afatinib is a highly selective inhibitor of EGFR and HER2 currently undergoing phase 1 trials for various solid tumors [15, 16]. It is a second-generation EGFR-TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and has shown promising results in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [17]. The LUX-lung clinical trial program was a phase 2b/3 randomized, double-blinded trial which showed promising results in NSCLC with a statistically significant increase in median PFS by 2 months. The main toxicities included diarrhea and skin rash which in most cases were managed by dose interruption or reduction [18]. There are currently phase 2 trials for BIBW2992 in metastatic (m) CRC. A phase 2 trial has been conducted by alternating BIBF 1120, a potent angiokinase inhibitor, and afatinib in 46 patients who already received several lines of chemotherapy. Seven patients remained progression-free after 16 weeks. Most of the patients tolerated the drugs with manageable toxicity [19]. Currently a phase 2 trial is ongoing (National Clinical Trial (NCT) 01152437), which compares the efficacy of cetuximab and afatinib. Patients with mCRC who had progressed on oxaliplatin or irinotecan and have not received any anti-EGFR therapy are eligible for the study. Patients with wild-type KRAS are randomized to cetuximab or afatinib, while those with mutant KRAS will receive afatinib.

(2) Necitumumab/IMC-11F8 —

Necitumumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody against EGFR [20]. Preclinical trials have shown that the efficacy of necitumumab can be compared to cetuximab [21]. Currently this drug is undergoing phase 3 trials for NSCLC. A phase 2 trial in CRC has been completed and has not been published. This study compared patients with mCRC either randomized to mFOLFOX-6 regimen or combination of necitumumab and mFOLFOX-6 (NCT 00835185). Preliminary data presented at 2008 annual American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting suggests that the combination is well tolerated with notable benefit in tumor activity [22, 23]. The median PFS (progression-free survival) or OS (overall survival) has not yet been reported.

(3) Erlotinib —

Erlotinib is an oral, reversible EGFR-TKI. Erlotinib has been approved for use in metastatic NSCLC in patients who have stable disease after 4–6 cycles of first-line chemotherapy, as a maintenance therapy [24]. Several trials have shown its efficacy as a first-line agent compared to standard chemotherapy in EGFR mutant patients with NSCLC [25]. Erlotinib has also been approved for its use in pancreatic cancer [26]. Erlotinib is being tested in a number of phase 2/3 trials in advanced CRC [27–30] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Phase 2 trials of erlotinib in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Status | Results | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erlotinib, capecitabine, and oxaliplatin | Completed | The arm with erlotinib showed higher response rate and PFS | NCT 00123851 |

| Erlotinib alternating with chemotherapy for second-line treatment | Unknown | Pending | NCT00642746 |

| Bevacizumab and erlotinib in combination with FOLFOX | Completed | High number of withdrawal due to toxicities limiting conclusion on efficacy | NCT00116506 |

| Capecitabine in combination with erlotinib | Terminated | 14 patients enrolled, severe toxicities median survival 76 weeks | NCT00459901 |

| Dual epidermal growth factor inhibition with erlotinib and panitumumab with and without chemotherapy | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00940316 |

| Erlotinib in treating patients with recurrent CRC | Completed | Pending | NCT00032110 |

| Dual inhibition of EGFR signaling using cetuximab and erlotinib | Active, not recruiting | Pending | NCT00784667 |

| Intermittent versus continuous Tarceva study | Completed | Pending | NCT01243047 |

| Erlotinib and combination chemotherapy in treating mCRC | Completed | Pending | NCT0049101 |

| Bevacizumab in combination with Xelox and Tarceva | Active, not recruiting | Pending | NCT01135498 |

| Erlotinib in treating patients with history of stage 1, 2, or 3 colorectal cancer or adenoma | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00754494 |

Table 2.

Phase 3 clinical trials of erlotinib in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Number of enrollment | Expected date of completion | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy and Avastin followed by maintenance treatment with Avastin ± Tarceva | 240 | December 2011 | NCT 00598156 |

| Combination chemotherapy and bevacizumab ± erlotinib in unresectable mCRC | 640 | Unknown | NCT00265824 |

(4) Gefitinib —

Gefitinib is a reversible EGFR-TKI used in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with EGFR mutation, approved in Europe [31] and not in the United States. It is currently being tested for mCRC in phase 2 clinical trials. A number of trials are under progress and a couple of them have been published. A phase 2 trial combining capecitabine and gefitinib as second-line therapy in advanced CRC showed no added efficacy and resulted in severe skin toxicities [32]. A trial involving combination of raltitrexed and gefitinib in one arm and raltitrexed alone has been tested on 76 patients as a second-line chemotherapy in advanced mCRC. This combination was well tolerated, but there was no difference in PFS between the arms [33]. The combination of FOLFOX-4 and gefitinib (IFOX) has been tested on previously untreated patients with mCRC. This trial showed increased efficacy in patients treated with IFOX when compared to FOLFOX-4 alone in a similar setting. The median OS was 20.5 months. Grade 3-4 diarrhea was reported in 67% patients, and Grade 3-4 neutropenia was reported in 60% of the patients, which is higher than FOLFOX-4 alone. The limitations of this study were that it does not have a control arm to compare efficacy [34]. Conflicting results were published on the efficacy of the combination of gefitinib and FOLFOX as first-line chemotherapy [35]. A multicenter phase 2 trial did not show any added benefit with gefitinib as a first-line agent [36]. A phase 2 randomized multicenter trial compared FOLFIRI to a combination of FOLFIRI and gefitinib and showed no overall benefit but has shown significant increase in toxicities [37]. All the above-mentioned phase 2 trials with gefitinib as first line or maintenance therapy in mCRC showed increased toxicities of gefitinib. Various phase 2 trials are being conducted on gefitinib in mCRC, and results are available from few trials [38, 39] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Phase 2 clinical trials of Gefitinib in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Status | Results | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRESSA + Xeloda after failure of first-line chemotherapy | Completed | Pending | NCT 00242788 |

| Gefitinib and combination chemotherapy in advanced or recurrent CRC | Completed | Pending | NCT 00052585 |

| Oxaliplatin ± gefitinib in metastatic or locally recurrent CRC | Completed | Gefitinib and oxaliplatin combination is ineffective in advanced CRC | NCT 00026299 |

| Gefitinib in treating patients with mCRC as a single agent | Completed | Gefitinib as a single agent is ineffective in advanced CRC | NCT 00025350 |

| ZD 1839 in treating patients with advanced CRC that has not responded to chemotherapy | Completed | Pending | NCT 00030524 |

3.2. Novel Drugs in Phase 1 Clinical Development That Act on EGFR

(1) Zalutumumab —

This is a novel human IgG1 monoclonal antibody against EGFR. It is currently being tested in phase 2 trials for squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, and the results appear to be encouraging [40]. A phase 1 study on zalutumumab and irinotecan in mCRC after failed irinotecan and cetuximab, presented at 2009 annual ASCO meeting, showed stable disease warranting further studies [41].

(2) Lapatinib —

This is an oral drug and a dual inhibitor of EGFR-TKI and HER2. It is currently undergoing phase 4 trials in HER 2 positive advanced metastatic breast cancer. A phase 1 trial in advanced solid tumors that includes mCRC has been published. It shows efficacy towards certain types of solid tumors [42]. Its efficacy and toxicities in a phase 2 CRC-specific studies are yet to be tested.

(3) Nimotuzumab —

An IgG1 human monoclonal antibody with efficacy in head and neck cancer is undergoing phase 2 clinical trials in China. It is being tested in combination with irinotecan, as a second-line agent for mCRC having wild-type KRAS (NCT 00972465).

3.3. Drugs Inhibiting RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway

Various targeted therapies that inhibit the components of this pathway are in clinical trials. The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK which is involved in regulation of cell cycle is activated in many cancers due to mutations in BRAF or RAS genes [43, 44]. This is a system of protein kinases where a member of RAF (A-RAF, B-RAF, and C-RAF) kinase phosphorylates and activates the MEK kinases (MEK1 and 2) which phosphorylates to further activate ERK1 and 2, which in turn phosphorylate to activate a number of substrates that are key components in cell cycle regulation. This pathway is coordinated by the binding of active RAS (HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS) to RAF [45].

(1) BMS-908662 —

This drug is a RAF inhibitor and currently undergoing phase 1/2 trials in mCRC alone or in combination with cetuximab in patients with mutated KRAS or BRAF. The study is recently completed, and the results are pending (NCT 01086267).

(2) MSC 1936369B —

This is a MEK inhibitor that is tested in phase 2 CRC studies. This is being investigated as a second-line agent in combination with FOLFORI in patients whose tumors harbor a KRAS mutation (NCT01085331).

(3) Selumetinib/AZD6244 —

This is an orally available drug and a selective inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2. The drug is currently undergoing phase 2 trials in colon cancer, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and biliary cancer [46]. A phase 2 randomized multicenter study comparing oral capecitabine and selumetinib as a second-line or third-line chemotherapy in advanced CRC demonstrated good tolerability and equal efficacy. The median PFS between both arms was not significantly different. The most common side effects reported in selumetinib are dermatitis, diarrhea, and asthenia [47]. This drug is currently being tested in many phase 2 trials in mCRC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Phase 2 clinical trials of selumetinib in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Status | Results | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| MK2206 and AZD6244 in patients with advanced colorectal cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT 01333475 |

| Phase 2 efficacy study of AZD6244 in colorectal cancer | Completed | Pending | NCT00514761 |

| Selumetinib + irinotecan as 2nd-line patients with KRAS and BRAF mutation | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01116271 |

(4) PLX 4032/Vemurafenib —

This drug is an oral selective inhibitor of oncogenic V600E mutant BRAF kinase. This mutation is found in up to 50% of patients with malignant melanoma but also found in a small subset of colorectal cancer patients. A phase 1 study is investigating this drug in mCRC (NCT00405587). Several studies have shown promising results in malignant melanoma leading to its approval by the USFDA for this indication [48]. A phase 1 trial evaluating the role of PLX 4032 in patients with advanced CRC with mutant BRAF was presented at 2010 annual ASCO meeting. The results were modest when compared to melanoma but clearly indicate that targeting mutant BRAF is a therapeutic option in colorectal cancer [49]. A preclinical study presented at 2012 annual Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, combining PLX4032 which is a BRAF inhibitor, and MEK inhibitor suggested synergistic effect of combined pharmacological blockade of the entire pathway [50].

(5) Sorafenib —

Sorafenib is an oral RAF and multitargeted TKI. Though initially discovered as potent RAF inhibitor, it is now know that it also inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). Its inhibiting action on RAF is in the order of RAF > wild-type BRAF > oncogenic B-RAF V600E [51]. Sorafenib is now FDA approved for its use in advanced renal cell carcinoma and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Its efficacy is now being tested in various solid tumors, and phase 2 trials are in progress for CRC. A phase 2 study was conducted in Saudi Arabia on 35 patients with mCRC who progressed on first-line chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to combination of cetuximab and sorafenib or cetuximab alone. Results show that the combination arm had higher partial response rate and an improved PFS especially in patients with wild-type KRAS status as compared to those with a mutation [52]. Several phase 2 trials of sorafenib in CRC are ongoing (Table 5).

Table 5.

Phase 2 clinical trials of sorafenib in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Status | Results | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib versus placebo + FOLFOX or FOLFORI in the second-line treatment of colorectal cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00889343 |

| Sorafenib + capecitabine in patients with pretreated advanced CRC | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01290926 |

| BAY 43-9006 plus cetuximab to treat colorectal cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00326495 |

| Sorafenib + FOLFORI in CRC after failure of oxaliplatin therapy | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00839111 |

| Sorafenib + capecitabine in previously treated CRC | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01471353 |

| Sorafenib + irinotecan in metastatic CRC and KRAS mutation | Completed | Pending | NCT00989469 |

| Sorafenib, cetuximab, and irinotecan in treating patients with mCRC | Ongoing, not recruiting | Pending | NCT00134069 |

| Sorafenib and bevacizumab versus single agent bevacizumab | Ongoing, not recruiting | Pending | NCT00826540 |

| External-Beam radiation therapy, capecitabine, and sorafenib in treating patients with locally advanced rectal cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00869570 |

(6) MEK 62/ARRY-438162 —

This is a potent selective inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2. This is currently in phases 1 and 2 trials for many advanced solid tumors with KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations (NCT01363232, NCT01337765, NCT01363232). A phase 1 multicenter study on the safety of MEK 62 on biliary cancer has been recently presented at 2012 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. The same study is being expanded to include patients with CRC with KRAS and BRAF mutations [53].

3.4. Drugs Inhibiting PI3 K-Akt-mTOR Pathway

This pathway is important for cell growth and survival. Abnormal activation of this pathway predisposes to development of many cancers, and genetic mutations in this pathway are common in many malignancies. Hence this pathway has gained importance in recent years as a target for drug development. Inhibitors of this pathway are in phases 1 and 2 clinical trials. PI3KCA mutations are seen in 25% of colorectal cancers [54]. Mutations in PTEN, AKT2, and PDK1 are also implicated in CRC [55]. PTEN inhibits this pathway, and loss of PTEN or mutation leads to increased cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis [56].

(1) MK-2206 —

This is an oral AKT inhibitor. A phase 2 trial of MK 2206 and AZD6244 in advanced CRC is recruiting patients. This trial aims at simultaneously blocking the PI3 K-AKT and RAS-MAPK pathways (NCT01333475). The first human phase 1 trial of MK 2206 in advanced solid tumors was recently published. The drug was well tolerated, showing AKT blockade. Toxicities reported were skin rash, nausea, purities, hyperglycemia, and diarrhea [57].

(2) Everolimus —

This is an oral derivative of rapamycin and approved by the FDA for management of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma who have failed one prior line of therapy [58]. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor approved in many countries to prevent rejection of solid organ transplants. A nonrandomized phase 2 trial on fifty metastatic colorectal cancer patients who failed first-line chemotherapy and cetuximab or panitumumab was enrolled in the study. Patients received bevacizumab every 2 weeks and daily everolimus. The drug was well tolerated. The median OS was 8.1 months showing only modest clinical efficacy [59]. There are many phase 2 trials under investigations in advanced CRC (Table 6).

Table 6.

Phase 2 clinical trials of everolimus in colorectal cancer.

| Study | Status | Results | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panitumumab, irinotecan, and everolimus as 2nd-line in wild-type KRAS | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01139138 |

| Efficacy and safety of everolimus with advanced CRC who failed prior chemo- and targeted therapy | Completed | Pending | NCT00419159 |

| Irinotecan, everolimus, and cetuximab in metastatic CRC with KRAS mutation | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01387880 |

| RAD001, FOLFOX, and bevacizumab in treatment of colorectal cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT01047293 |

| Bevacizumab and everolimus in mCRC as a 2nd-line therapy | Completed | Pending | NCT00597506 |

| Phase 2 trial of RAD001 in refractory colorectal cancer | Completed | Pending | NCT00337545 |

| RAD001 and AV-951 in metastatic CRC | Ongoing, not recruiting | Pending | NCT01058655 |

| Safety study of rapamycin administered before and during radiotherapy to treat rectum cancer | Recruiting | Pending | NCT00409994 |

(3) Temsirolimus —

This is an intravenous mTOR inhibitor approved by the USFDA for advanced renal cell carcinoma [60]. It is currently undergoing phase 4 clinical trials in mantle cell lymphoma. This drug is currently in phases 1 and 2 trials for advanced CRC. This drug has been evaluated in patients with KRAS mutation whose cancer was irinotecan resistant, and the results are yet to be reported. (NCT00827684). Rare but serious side effects include interstitial lung disease, acute renal failure, and bowel perforation.

4. Discussion

Despite recent advances in our knowledge at the molecular level of colorectal cancer, the prognosis still remains poor. The 5-year survival rate in a tertiary oncology center in the United States is around 10% for advanced CRC [61]. Though the 5-year survival rate has not changed with the recent advances, the 2-year survival rate significantly improved for metastatic colorectal cancer, around 40 percent in recent years compared to 20 percent a decade ago [62]. Chemotherapy still remains the mainstay of treatment [63]. Combining traditional chemotherapy with targeted therapies has shown benefit in several studies [64–66]. With this idea in mind and with preclinical data of the efficacy of the combination of anti-EGFR and anti-VEGF therapy, clinical trials were launched. However, the activity observed in preclinical studies did not hold its ground once the clinical results were announced. In CAIRO2 (capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer) and PACCE (panitumumab advanced colorectal cancer evaluation study) trials, the addition of anti-EGFR antibody to a combination of chemotherapy and bevacizumab significantly reduced the PFS [67, 68]. Targeted drug therapy is a rapidly emerging field, but lack of specific biomarkers to channelize the treatment only to the subset of patients who get benefit from it still remains unsolved.

The resistance to cetuximab and panitumumab in patients with KRAS mutation is well known. It is now a standard of care to evaluate for KRAS mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer [13, 69–72]. While KRAS mutation is an excellent well-documented marker of exclusion, it is not, however, a reliable marker of inclusion. In spite of excluding the patients with a KRAS mutation in their cancer from receiving anti-EGFR therapy, the response rates in the patients with WT KRAS are of the order of 17%–60% [6, 13, 69, 70, 73–75]. More importantly, there appears to be a negative outcome when patients with a KRAS mutation are treated with the anti-EGFR drugs [76, 77]. This suggests that there are other potential markers of resistance [78]. This search for other biomarkers of resistance has mainly revolved around the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and the PI3 K-AKT-mTOR-PTEN pathway.

Some studies indicate that BRAF mutations (around 10% in CRC), which are further downstream of the KRAS gene, are markers of resistance to cetuximab or panitumumab. Further studies have now indicated that BRAF is a better prognostic rather than a predictive biomarker [10, 79–84]. Patients with this mutation have poorer prognosis and appear to respond less robustly to the anti-EGFR antibodies [10]. The routine testing of BRAF has still not found its place in clinical practice. As regards the PI3 K-PTEN pathway, multiple components of the pathway have been implicated in its aberration; leading to its overactivity including mutations in PIK3CA, PTEN, PIK3R1 (regulatory subunit of the PIK3CA gene), p85α [85], and AKT1. Furthermore, loss of PTEN expression in CRC has been shown to be mediated by promoter hypermethylation [86, 87].

A number of studies indicate that loss of PTEN is associated with poorer outcomes in metastatic CRC and a less robust response when therapy is indicated with the anti-EGFR drugs. Our group was one of the first to demonstrate in vitro that mutations in the PIK3CA gene and loss of PTEN expression predicted for resistance to cetuximab in a panel of CRC cell lines [88]. Since then, several clinical studies have been reported, with conflicting results; with some reports suggesting a predictive role of this pathway and others refuting this finding [11, 89–96]. Notably, a recent report suggested that mutations in exon 20 of PIK3CA specifically predicted for resistance to cetuximab [93]. When initially approved, the use of cetuximab was restricted to patients whose tumors “over expressed EGFR” as documented by IHC staining; however, subsequently this restriction was removed when clinical evidence did not support this approach. Baseline EGFR in determining response to cetuximab remains controversial with studies differing in their results [96, 97].

As further data regarding the role of the PI3 K pathway evolves, there is the potential to markedly improving the clinical benefit rate and excluding almost 60–70% of patients from the use of anti-EGFR therapy. While we continue to refine the use of drugs already available, there is clearly a need for newer drug approaches that may be useful in this deadly cancer. The drugs mentioned in this paper offer a beacon of hope on the horizon that approaches targeting the EGFR and its downstream pathways are abundant. The key question is going to be whether the further development of these drugs should be biomarker driven or should it be tested in all comers. There are risks and benefits to both of these approaches. The need for further biomarkers in both clinical practice and the process of drug development is urgent to enable clinicians to predict responses to different targeted therapies. Many targeted drugs are in phase 2 and 3 trials, the results are being waited to incorporate them in the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a K-12 Award from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (1K12CA132783-01A1 to S. Goel) and an Advanced Clinical Research Award (ACRA) in colon cancer, by the ASCO (now Conquer) Cancer Foundation to S. Goel.

References

- 1. Colorectal Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society, 2011–2013.

- 2.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(12):2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tol J, Punt CJA. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. Clinical Therapeutics. 2010;32(3):437–453. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(6):563–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lièvre A, Bachet J-B, Boige V, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(3):374–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabbinavar FF, Hambleton J, Mass RD, Hurwitz HI, Bergsland E, Sarkar S. Combined analysis of efficacy: the addition of bevacizumab to fluorouracil/leucovorin improves survival for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(16):3706–3712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. The EGF receptor family as targets for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19(56):6550–6565. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams R, Maughan T. Predicting response to epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2007;7(4):503–518. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(35):5705–5712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frattini M, Saletti P, Romagnani E, et al. PTEN loss of expression predicts cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;97(8):1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sood A, McClain D, Maitra R, et al. PTEN gene expression and mutations in the PIK3CA gene as predictors of clinical benefit to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapy in patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(10):1626–1634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li FH, Shen L, Li ZH, et al. Impact of KRAS mutation and PTEN expression on cetuximab-treated colorectal cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(46):5881–5888. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i46.5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap TA, Vidal L, Adam J, et al. Phase I trial of the irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor BIBW 2992 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(25):3965–3972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minkovsky N, Berezov A. BIBW-2992, a dual receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of solid tumors. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 2008;9(12):1336–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsh V. Afatinib (BIBW 2992) development in non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncology. 2011;7(7):817–825. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metro G, Crinò L. The LUX-Lung clinical trial program of afatinib for non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2011;11(5):673–682. doi: 10.1586/era.11.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouche O, Maindrault-Goebel F, Ducreux M, et al. Phase II trial of weekly alternating sequential BIBF 1120 and afatinib for advanced colorectal cancer. Anticancer Research. 2011;31(6):2271–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuenen B, Witteveen PO, Ruijter R, et al. A phase I pharmacologic study of necitumumab (IMC-11F8), a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against EGFR in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(6):1915–1923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dienstmann R, Tabernero J. Necitumumab, a fully human IgG1 mAb directed against the EGFR for the potential treatment of cancer. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 2010;11(12):1434–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dienstmann R, Felip E. Necitumumab in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: translation from preclinical to clinical development. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2011;11(9):1223–1231. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.595709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabernero J, Sastre Valera J, Delaunoit T. A phase 2 study of IMC-11F8, a monoclonal antibody directed against the EGFR, in combination with mFOLFOX-6 chemotherapy in the first- line treatment of advanced or metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(supplement) abstract no. 4066. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11(6):521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(8):735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(15):1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyerhardt JA, Zhu AX, Enzinger PC, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and erlotinib in previously treated patients with metastastic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(12):1892–1897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyerhardt JA, Stuart K, Fuchs CS, et al. Phase II study of FOLFOX, bevacizumab and erlotinib as first-line therapy for patients with metastastic colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18(7):1185–1189. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozuch P, Malamud S, Wasserman C, Homel P, Mirzoyev T, Grossbard M. Phase II trial of erlotinib and capecitabine for patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2009;8(1):38–42. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2009.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bijnsdorp IV, Kruyt FAE, Fukushima M, Smid K, Gokoel S, Peters GJ. Molecular mechanism underlying the synergistic interaction between trifluorothymidine and the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Cancer Science. 2010;101(2):440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trarbach T, Reinacher-Schick A, Hegewisch-Becker S, et al. Gefitinib in combination with capecitabine as second-line therapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer (aCRC): a phase I/II study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Onkologie. 2010;33(3):89–93. doi: 10.1159/000277635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viéitez JM, Valladares M, Peláez I, et al. A randomized phase II study of raltitrexed and gefitinib versus raltitrexed alone as second line chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer. (1839IL/0143) Investigational New Drugs. 2010;29(5):1038–1044. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher GA, Kuo T, Ramsey M, et al. A phase II study of gefitinib, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in previously untreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(21):7074–7079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geulibter AJ, Gamucci T, Pollera CF, et al. A phase II trial of gefitinib in combination with capecitabine and oxaliplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2007;23(9):2117–2123. doi: 10.1185/030079907X226113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cascinu S, Berardi R, Salvagni S, et al. A combination of gefitinib and FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer patients. A GISCAD multicentre phase II study including a biological analysis of EGFR overexpression, amplification and NF-kB activation. British Journal of Cancer. 2008;98(1):71–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santoro A, Comandone A, Rimassa L, et al. A phase II randomized multicenter trial of gefitinib plus FOLFIRI and FOLFIRI alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(11):1888–1893. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kindler HL, Friberg G, Skoog L, Wade-Oliver K, Vokes EE. Phase I/II trial of gefitinib and oxaliplatin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;28(4):340–344. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000159558.19631.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothenberg ML, LaFleur B, Levy DE, et al. Randomized phase II trial of the clinical and biological effects of two dose levels of gefitinib in patients with recurrent colorectal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(36):9265–9274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bastholt L, Specht L, Jensen K, et al. Phase I/II clinical and pharmacokinetic study evaluating a fully human monoclonal antibody against EGFr (HuMax-EGFr) in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2007;85(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mano M. Phase I trial of zalutumumab and irinotecan in metastatic colorectal cancer patients who have failed irinotecan- and cetuximab-based therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(supplement) abstract no. e15028. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dennie TW, Fleming RA, Bowen CJ, et al. A phase I study of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and lapatinib in metastatic or advanced solid tumors. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(1):57–62. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2011.n.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolch W, Kotwaliwale A, Vass K, Janosch P. The role of Raf kinases in malignant transformation. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2002;4(8):1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy. Cancer Letters. 2009;283(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little AS, Balmanno K, Sale MJ, Smith PD, Cook SJ. Tumour cell responses to MEK1/2 inhibitors: acquired resistance and pathway remodelling. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2012;40(1):73–78. doi: 10.1042/BST20110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel SP, Kim KB. Selumetinib (AZD6244; ARRY-142886) in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2012;21(4):531–539. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.665871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennouna J, Lang I, Valladares-Ayerbes M, et al. A Phase II, open-label, randomised study to assess the efficacy and safety of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus capecitabine monotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. Investigational New Drugs. 2010;29(5):1021–1028. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(8):707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopetz S, Desak J, Chan E, et al. PLX4032 in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with mutant BRAF tumors. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(15, abstract no. 3534) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higgins B, Kolinsky KD, Yangetal H. Efficacy of vemurafenib, a selective BRAFV600E inhibitor, in combination with a MEK inhibiotor in BRAFV600E collorectal cancer models. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(supplement 4) Abstract no. 488. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Research. 2004;64(19):7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galal KM, Khaled Z, Mourad AMM. Role of cetuximab and sorafenib in treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Indian Journal of Cancer. 2011;48(1):47–54. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.75825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finn RS, Javle MM, Tan BR, et al. A phase I study of MEK inhibitor MEK162 (ARRY-438162) in patients with biliary tract cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(supplement 4) Abstract no. 220. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304(5670, article 554) doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(12):988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stambolic V, Suzuki A, De la Pompa JL, et al. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yap TA, Yan L, Patnaik A, et al. First-in-man clinical trial of the oral pan-AKT inhibitor MK-206 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(35):4688–4695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. The Lancet. 2008;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altomare I, Bendell JC, Bullock KE, et al. A phase II trial of bevacizumab plus everolimus for patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16(8):1131–1137. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kwitkowski VE, Prowell TM, Ibrahim A, et al. FDA approval summary: temsirolimus as treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncologist. 2010;15(4):428–435. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrarotto R, Pathak P, Maru D, et al. Durable complete responses in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy alone. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(3):178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Platell C, Ng S, O’Bichere A, Tebbutt N. Changing management and survival in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2011;54(2):214–219. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182023bb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lucas AS, O'Neil BH, Goldberg RM. A decade of advances in cytotoxic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(5):663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, et al. EPIC: phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(14):2311–2319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(12):1539–1544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tol J, Koopman M, Rodenburg CJ, et al. A randomised phase III study on capecitabine, oxaliplatin and bevacizumab with or without cetuximab in first-line advanced colorectal cancer, the CAIRO2 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG). An interim analysis of toxicity. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(4):734–738. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hecht JR, Mitchell E, Chidiac T, et al. A randomized phase IIIB trial of chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and panitumumab compared with chemotherapy and bevacizumab alone for metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(5):672–680. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lièvre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Research. 2006;66(8):3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Roock W, Piessevaux H, De Schutter J, et al. KRAS wild-type state predicts survival and is associated to early radiological response in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(3):508–515. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Fiore F, Blanchard F, Charbonnier F, et al. Clinical relevance of KRAS mutation detection in metastatic colorectal cancer treated by Cetuximab plus chemotherapy. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;96(8):1166–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lièvre A, Laurent-Puig P. Genetics: predictive value of KRAS mutations in chemoresistant CRC. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2009;6(6):306–307. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freeman DJ, Juan T, Reiner M, et al. Association of K-ras mutational status and clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving panitumumab alone. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7(3):184–190. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Research. 2007;67(6):2643–2648. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(17):1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT, et al. KRAS status and efficacy of first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with FOLFOX with or without cetuximab: the OPUS experience. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(supplement) abstract no. 4000. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Punt CJ, Tol J, Rodenburg CJ, et al. Randomized phase III study of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab with or without cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer (ACC), the CAIRO2 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(supplement) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm607. abstract no. LBA4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linardou H, Dahabreh IJ, Kanaloupiti D, et al. Assessment of somatic k-RAS mutations as a mechanism associated with resistance to EGFR-targeted agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and metastatic colorectal cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9(10):962–972. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Cremolini C, et al. KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(4):715–721. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tol J, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJA. BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(1):98–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(35):5931–5937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Cutsem E, Lang I, Folprecht G, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFIRI: final data from the CRYSTAL study on the association of KRAS and BRAF biomarker status with treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(supplement 15, article 15s) abstract no. 3570. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tejpar S, Bertagnolli M, Bosman F, et al. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in resected colon cancer: current status and future perspectives for integrating genomics into biomarker discovery. Oncologist. 2010;15(4):390–404. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, et al. American society of clinical oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(12):2091–2096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Philp AJ, Campbell IG, Leet C, et al. The phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase p85α gene is an oncogene in human ovarian and colon tumors. Cancer Research. 2001;61(20):7426–7429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guanti G, Resta N, Simone C, et al. Involvement of PTEN mutations in the genetic pathways of colorectal cancerogenesis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000;9(2):283–287. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goel A, Arnold CN, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN by promoter hypermethylation in microsatellite instability-high sporadic colorectal cancers. Cancer Research. 2004;64(9):3014–3021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-2401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jhawer M, Goel S, Wilson AJ, et al. PIK3CA mutation/PTEN expression status predicts response of colon cancer cells to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab. Cancer Research. 2008;68(6):1953–1961. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prenen H, De Schutter J, Jacobs B, et al. PIK3CA mutations are not a major determinant of resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(9):3184–3188. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Perrone F, Lampis A, Orsenigo M, et al. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(1):84–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Loupakis F, Pollina L, Stasi I, et al. PTEN expression and KRAS mutations on primary tumors and metastases in the prediction of benefit from cetuximab plus irinotecan for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(16):2622–2629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Research. 2009;69(5):1851–1857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11(8):753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mao C, Liao RY, Chen Q. Loss of PTEN expression predicts resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;102(5, article 940) doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Molinari F, Martin V, Saletti P, et al. Differing deregulation of EGFR and downstream proteins in primary colorectal cancer and related metastatic sites may be clinically relevant. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;100(7):1087–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Laurent-Puig P, Cayre A, Manceau G, et al. Analysis of PTEN, BRAF, and EGFR status in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(35):5924–5930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Molinari F, Frattini M. KRAS mutational test for metastatic colorectal cancer patients: not just a technical problem. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2012;12(2):123–126. doi: 10.1586/erm.11.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]