Abstract

AIM

Asymptomatic subjects volunteering for research studies are generally stratified as healthy based on a questionnaire, medical interviewing, and physical examination. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of upper GI abnormalities in healthy asymptomatic volunteers using unsedated transnasal esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (T-EGD) with an ultrathin endoscope as an additional screening tool.

METHODS

This is a prospective study from one academic medical center with extensive experience in T-EGD. Consecutive 150 subjects volunteering for research studies were initially screened by using a gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) questionnaire, interviewing, and examination. Based on these, they were stratified as healthy asymptomatic volunteers or with GERD. Unsedated T-EGD was then performed by a faculty who was blinded to the results of the initial assessment.

RESULTS

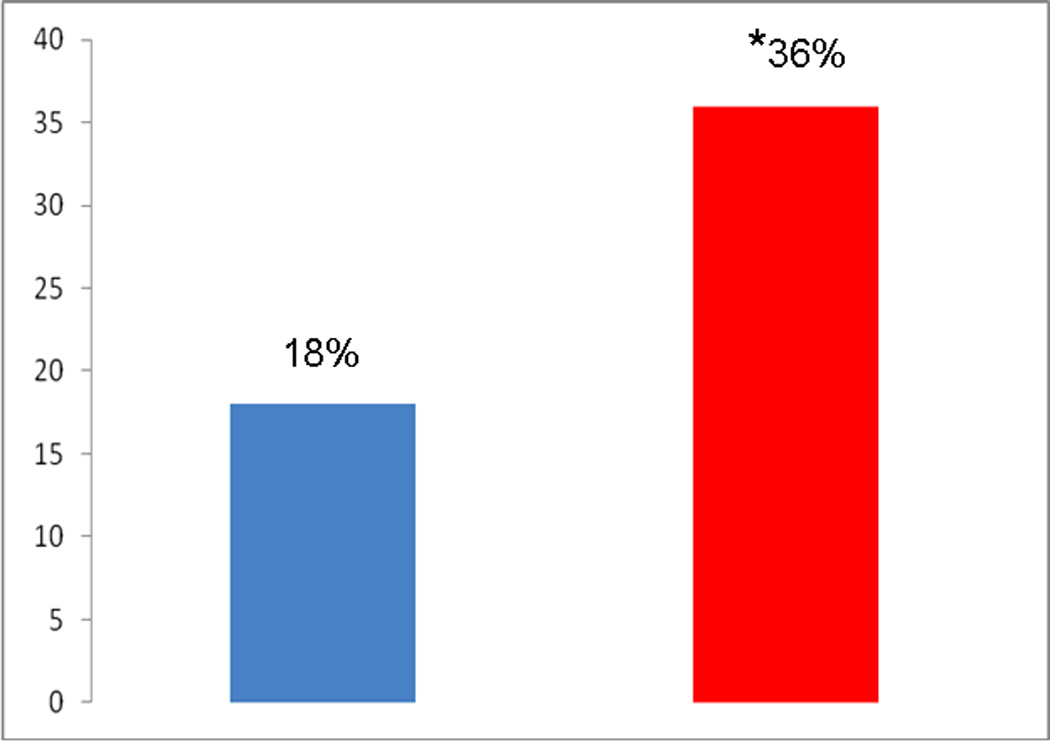

On initial assessment using GERD questionnaire, medical interviewing, and physical examination, of the total 150 consecutive research volunteers, 83 (33±16, 46 females, 37 males) subjects were healthy asymptomatic volunteers and 67 (36±15, 35 females, 32 males) had symptoms of GERD. On T-EGD, gastrointestinal pathology was found in 15 of 83 (18%) healthy asymptomatic volunteers as compared to 24 of 67 (36%) stratified as having GERD (p <0.01). The esophageal abnormalities found in healthy asymptomatic volunteers were esophagitis (13.3%), Barrett’s esophagus (2.4%), hiatus hernia (2.4%) and gastritis (2.4%).

CONCLUSION

A small but significant number of asymptomatic subjects have abnormal upper GI findings. Hence, transnasal unsedated endoscopy can be considered as a screening tool to stratify subjects as healthy especially when considering them for research studies.

Keywords: Transnasal endoscopy, unsedated endoscopy, ultrathin endoscope, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barretts esophagus

INTRODUCTION

Subjects participating in upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract research studies are stratified as being healthy asymptomatic volunteers based on using standardized written health questionnaires, medical interviewing and physical examination. However, using conventional upper GI endoscopy (C-EGD), previous studies have shown abnormalities in the upper GI tract in a significant number of asymptomatic subjects [1,2]. Despite this observation, routine use of C-EGD as a screening tool to stratify research volunteers has not received wide-spread acceptance for many reasons. C-EGD involves administering moderate sedation which has associated cardio-pulmonary risks [3,4,5]. Because of sedation, the subjects have to take the day off and arrange for transportation to go home. Routine use of C-EGD for research screening is also expensive and a significant proportion of the direct and indirect costs (time off work) is related to moderate sedation. Besides these, there are logistic issues in scheduling research volunteers for endoscopy in GI laboratories that otherwise are busy with clinical work load.

In 1994, Shaker et al [6] evaluated a technique of performing upper GI endoscopy transnasally without moderate sedation (unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy, T-EGD). In this technique, the subject is in the sitting upright position and an ultrathin endoscope is passed transnasally after the nostril is numbed with local anesthetic agent. Subsequent studies have shown this technique to be comparable to C-EGD in terms of diagnostic accuracy and T-EGD was more acceptable, better tolerated and cheaper compared to C-EGD [7,8,9]. Besides a questionnaire, medical interviewing, and physical examination, we have incorporated T-EGD as a screening tool to stratify research volunteers.

The aim of this study was to prospectively evaluate the impact of T-EGD as a screening tool for identifying upper GI lesions in asymptomatic apparently healthy subjects and compare them to those with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin and all subjects gave informed and written consent.

One hundred and fifty consecutive subjects presenting for research studies on the upper GI tract were enrolled in the study. These studies primarily were focused on research on the laryngo-pharynx, esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers and on those with GERD. All subjects filled out 3 forms that included systemic review, clinical review and Mayo-GERD questionnaire [10]. They also underwent medical interviewing and a physical examination. Based on these, subjects were stratified as healthy asymptomatic volunteers or those with GERD or GERD-type symptoms. Patients and volunteers with other comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, or voice disorders were excluded. All subjects then underwent T-EGD using previously described techniques [6,7]

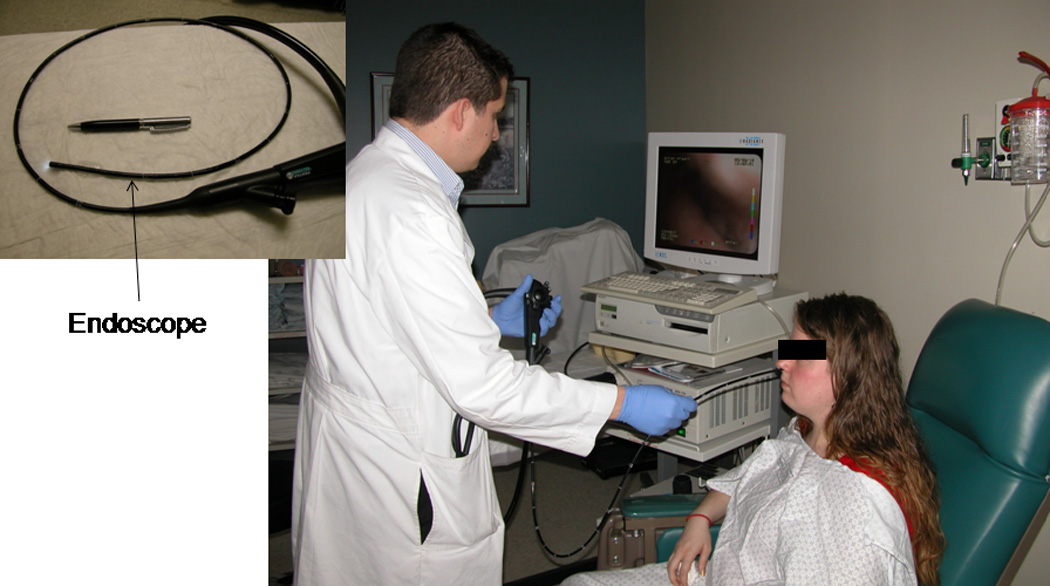

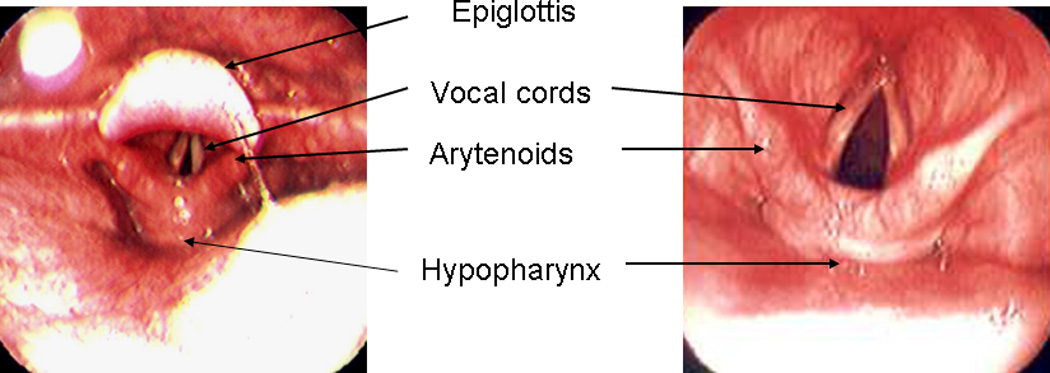

T-EGD was performed with the subjects in the sitting upright position (Figure 1). None of the subjects received sedation. Using a cotton-tipped applicator covered with 2% lidocaine gel (Akorn Inc., Lake Forest, IL) the more patent nostril was identified and was anesthetized up to the nasopharynx. The pharynx was anesthetized using 4% lidocaine spray (Roxane laboratories, Columbus, Ohio). An ultra-thin (EG-1580 k, PENTAX Medical Company, Montvale, NJ) endoscope with an outer diameter of 5.1mm was passed through the nostril and the pharynx, larynx, vocal cords and hypopharynx were carefully examined (Figure 2) . This endoscope has a working length of 1050 mm with a 210 degree up/down angulation and a 140° angle of view. Under direct vision, the endoscope was then passed through the upper esophageal sphincter into the esophagus. The distance from the nares to the Z-line and the diaphragm hiatus were noted. The stomach was then entered and examined in the forward and retroflexed views. The duodenum was then intubated and examined up to the second part. Where indicated, biopsies were also obtained (for example in suspected Barrett’s esophagus). Those found to have abnormal findings requiring treatment were asked to contact their primary doctor and a report was also sent out.

Figure 1.

Transnasal unsedated esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy using an ultrathin endoscope (5.1mm diameter) with the patient in the sitting upright position.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic views of the pharynx and larynx using the thin endoscope

The physician performing the T-EGD was blinded to the results of the Mayo-GERD questionnaire [10], medical interviewing and physical examination. The T-EGD was video recorded and then independently reviewed by another examiner who was blinded to the patient information and results of the initial T-EGD report.

Descriptive statistics such as mean age, gender ratio and prevalence of abnormal findings on T-EGD are presented for the healthy asymptomatic group as well as those with GERD symptoms. Continuous data is expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are compared using the Chi-square test and Fischer’s exact test where appropriate. A p-value = 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using Stats Direct statistical software (version 2.5.7, StatsDirect Ltd, UK).

RESULTS

A total of 150 consecutive volunteers were studied. Based on the questionnaires, medical interviewing and physical examination, 83 (age 33±16SD years, 46 females, 37 males) subjects were stratified as healthy asymptomatic volunteers and 67 (36±15, 35 females, 32 males) with GERD symptoms. All subjects completed the T-EGD and tolerated the procedure well. One patient had mild self-limited epistaxis that did not require any further medical treatment. There were no other complications.

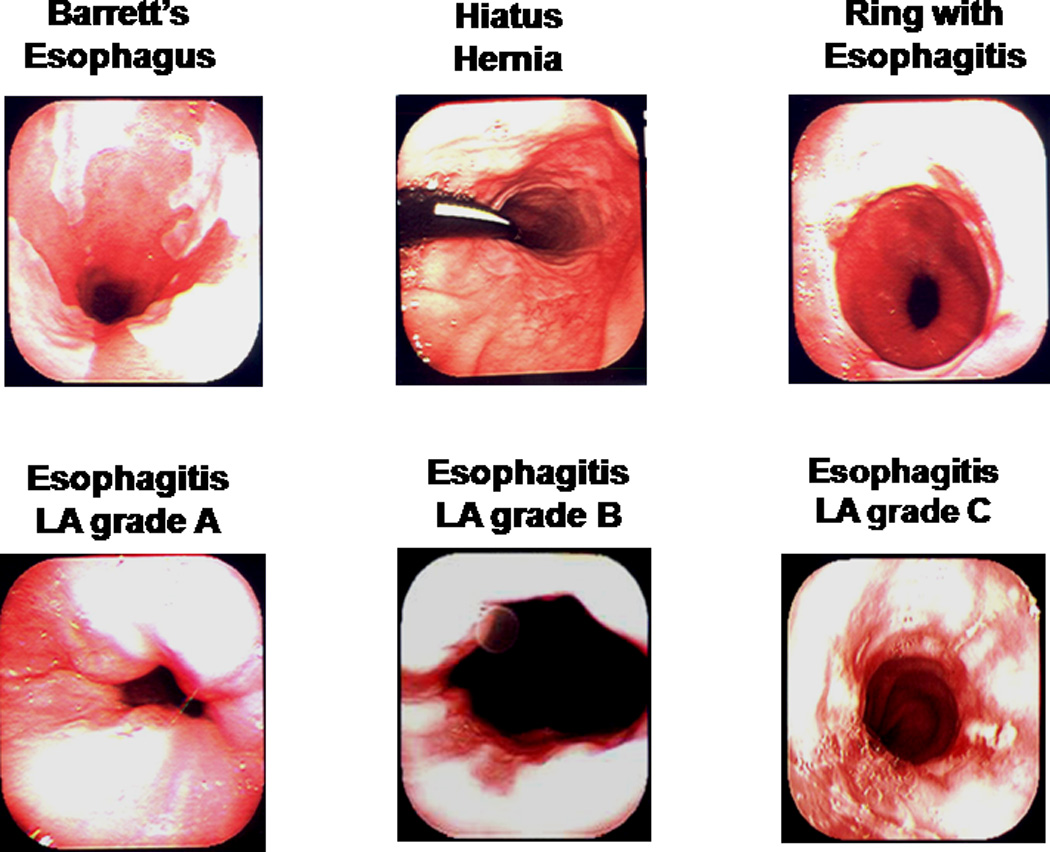

Despite having no symptoms and being apparently healthy, T-EGD identified a lesion in the UGI tract in up to 18% (15 of 83) of these individuals (Figure 3). These lesions included esophagitis (13.3%), Barrett’s esophagus (2.4%), hiatal hernia (2.4%) and gastritis (2.4%) (Table 1, Figure 4). A shown in the table, some of these subjects had more than one type of lesion. Compared to these findings, T-EGD identified a lesion in 36% (24 of 67, p <0.01) of volunteers with GERD symptoms (Figure 3). The lesions found in these subjects included esophagitis (25.4%), Barrett’s esophagus (3%), hiatal hernia (9%), gastritis (3%), inlet patch (4.5%) and esophageal ring (10.5%) (Table1). While esophagitis, hiatal hernia and esophageal ring were more common in those with GERD symptoms, the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and gastritis was similar between the two groups.

Figure 3.

Abnormal findings on T-EGD (%) in healthy research volunteers compared to those with GERD symptoms

*P<0.01

TABLE 1.

Abnormal T-EGD findings in Healthy and those with GERD

| Healthy (n=83) | GERD (n=67) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Normal | 68(82) | 43(64) |

| LA-grade A Esophagitis | 8 (9.6) | 13(19.4)* |

| LA-grade B Esophagitis | 2(2.4) | 3(4.5) |

| LA-grade C Esophagitis | 1(1.2) | 1(1.5) |

| Total Esophagitis | 11(13.3) | 17(25.4)* |

| Barrett’s | 2(2.4) | 3(4.5) |

| Hiatal Hernia | 2(2.4) | 6(9)* |

| Gastritis | 2(2.4) | 2(3) |

| Inlet patch | 0 | 3(4.5)* |

| Ring | 1 (1.2) | 7(10.5)* |

| Total | 15(18%) | 24(36%)* |

P<0.01

Figure 4.

Some abnormal endoscopic findings in apparently healthy research volunteers

DISCUSSION

Routinely, subjects enrolled for research studies on the upper GI tract are stratified as being healthy based on symptom questionnaires, medical interviewing and physical examination. However, using conventional upper GI endoscopy (C-EGD), prior studies have shown presence of upper GI tract abnormalities, including serious conditions in asymptomatic “healthy” subjects. In a prospective study by Akdamar et al [1], on healthy, asymptomatic, volunteers who were screened using C-EGD prior to entering clinical trials, point prevalence for erosive esophagitis was 8.5% [1]. In another study on 54 asymptomatic healthy volunteers undergoing clinical pharmacological studies, using C-EGD, Ecclissato et al [2] found abnormalities in upper GI tract in a significant proportion of subjects. These primarily included peptic lesions and erosive esophagitis. Had C-EGD not been used as a screening tool, these apparently “healthy” control asymptomatic subjects could have significantly affected the outcome of these clinical studies. These findings may have implications also on other studies using healthy asymptomatic subjects as control volunteers without endoscopic screening.

Despite the above findings, C-EGD is not routinely used as a screening tool to stratify volunteers presenting for research studies on the upper GI tract. Oxygen desaturation and cardio pulmonary risks are a major concern with moderate sedation routinely used for C-EGD [3,4,5]. Over 50% of deaths that are associated with upper GI endoscopy are due to cardiopulmonary complications [4]. In a study evaluating the cardiac risks of 146 patients undergoing elective UGI endoscopy serious electrocardiographic changes were noted in 21 patients [5]. In addition to medical risks, use of C-EGD as a screening tool also carries a significant economic and social burden because of the associated direct and indirect costs (pre- and post-procedural monitoring, medication charges, time off from work, need for separate transportation) [8]. Scheduling research volunteers for screening in GI laboratories with heavy patient work load may raise logistic issues.

To overcome the above issues, in the present study, we successfully used unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (T-EGD) using an ultrathin endoscope as a screening tool to stratify our research volunteers. This procedure can be done in an office setting and does not require sedation. In 1994, Shaker evaluated this technique in 20 volunteers and found it to be safe and feasible [6]. In a comparative study where each subject underwent both C-EGD and T-EGD, Dean et al [7], showed T-EGD to have similar diagnostic accuracy rates and was more tolerable and acceptable to the subjects. Other comparative studies between the T-EGD and C-EGD techniques showed similar results [8,9]. Comparing T-EGD with C-EGD, Craig et al [9] showed that T-EGD required a shorter procedure time (15 vs 20 min), shorter time to recover (7 vs 37 min), 65% reduction in consumable costs, and 92% reduction in pharmaceutical costs. Since then this technique has been studied and validated in multiple research studies [11,12,13,14,15,16].

As a screening tool, T-EGD was found to be similar to C-EGD in the evaluation of Helicobacter pylori diagnosis and eradication [11]. In another study T-EGD was successfully used in screening cirrhotic patients for esophageal varices [12]. T-EGD has also been used for screening for Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia [13] and for placing feeding tubes [14,15,16]

In view of above advantages of T-EGD, we have incorporated T-EGD as a screening tool for all our research volunteers presenting for research studies on the upper GI tract and in this study we prospectively evaluated the impact of this approach. Similar to studies using C-EGD but without its disadvantages, this study using T-EGD has shown that even those who have been stratified as “healthy” based on medical questionnaires, interviewing and medical examination have a small but significant percentage of upper GI lesions (15 of 83; 18%). Esophagitis was the most predominant abnormality in this asymptomatic group and without T-EGD these subjects would have otherwise been included as “healthy” controls for research on GERD. This could have confounded the outcomes of these studies.

Esophageal abnormalities may also be found in up to 30% of patients with LPR [17]. Interestingly, having excluded subjects with symptoms suggestive of LPR, in our study 36% of those with GERD or GERD-like symptoms also had abnormal esophageal findings on T-EGD. Hence similar to LPR, even in those with GERD or GERD-like symptoms, only 1/3 will show macroscopic esophageal abnormalities on endoscopic evaluation.

Since several research studies have used volunteers who are healthy and asymptomatic as controls or for physiological studies, the intention of our study was to determine if these volunteers are indeed “healthy” or have abnormal findings on transnasal endoscopy. Our intentions were not to validate the Mayo GERD questionnaire [10]. Correlation of GERD symptoms as measured by the Mayo questionnaire with 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring has been studied before [18]. Even if the correlation is weak, volunteers with GERD-like symptoms still cannot be classified as being asymptomatic subjects for research studies. Moreover, negative endoscopic findings in these patients cannot entirely exclude gastroesophageal reflux since they may have nonerosive reflux disease (NERD). Hence we separated this group from those with no symptoms.

Abnormal endoscopic findings in volunteers with GERD or GERD-type symptoms (using any questionnaire) can be expected and hence, this was not the primary focus of our study. Rather, emphasis was given to the presence or absence of abnormal esophageal endoscopic findings in subjects with no GERD or GERD-type symptoms (in our case, using the Mayo GERD questionnaire).

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted to assess the upper gastrointestinal tract in apparently healthy asymptomatic volunteers using an ultrathin endoscope and the unsedated transnasal approach of upper GI endoscopy in an office setting. Due to its comparable diagnostic yield and avoidance of sedation related medical as well as economic risks, we believe that T-EGD should become a routine screening tool in the stratification of research subjects prior to participation in studies on upper GI tract. Furthermore, it would allow for reduced sample sizes for research studies given that it would provide more power to detect differences among groups being studied.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This work is supported in part by NIH grants: 1P01DK068051-01A1 and 5RO1DK025731.

Abbreviations

- T-EGD

Unsedated transnasal esophagogastoduodenoscopy

- C-EGD

Conventional esophagogastoduodenoscopy

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GI

Gastrointestinal

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the Digestive Disease Week 2009 and at the annual meeting of Dysphagia Research Society, 2010.

Disclosure:

None of the authors of this manuscript have any potential conflicts (financial, professional, or personal) that are relevant to the manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Robert M. Siwiec: Study design, administered questionnaire, physical examination, performed transnasal endoscopy, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Kulwinder S Dua: Study design, administered questionnaire, physical examination, performed transnasal endoscopy, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Sri Naveen Surapaneni: Study design, administered questionnaire, physical examination, performed transnasal endoscopy, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Mohammed Hafeezullah: Volunteer recruitment, data collection, and data analysis.

Benson Massey: Performed transnasal endoscopy

Reza Shaker: Study design, performed transnasal endoscopy, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akdamar K, Ertan A, Agrawal NM, McMahon FG, Ryan J. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in normal asymptomatic volunteers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:78–80. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(86)71760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ecclissato C, Carvalho AF, Ferraz JG, de Nucci G, De Souza CA, Pedrazzoli J., Jr Prevalence of peptic lesions in asymptomatic, healthy volunteers. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:403–406. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(01)80011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma VK, Nguyen CC, Crowell MD, et al. A national study of cardiopulmonary unplanned events after GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connor KW, Jones S. Oxygen desaturation is common and clinically underappreciated during elective endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S2–S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman DA, Wuerker CK, Katon RM. Cardiopulmonary risk of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Role of endoscope diameter and systemic sedation. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:468–472. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaker R. Unsedated trans-nasal pharyngoesophagogastroduodenoscopy (T-EGD): technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:346–348. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean R, Dua K, Massey B, Berger W, Hogan WJ, Shaker R. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:422–424. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bampton PA, Reid DP, Johnson RD, Fitch RJ, Dent J. A comparison of transnasal and transoral oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig A, Hanlon J, Dent J, Schoeman M. A comparison of transnasal and transoral endoscopy with small-diameter endoscopes in unsedated patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:292–296. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(6):539–547. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saeian K, Townsend WF, Rochling FA, Bardan E, Dua K, Phadnis S, Dunn BE, Darnell K, Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal EGD: an alternative approach to conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy for documenting Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saeian K, Staff D, Knox J, Binion D, Townsend W, Dua K, Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy: a new technique for accurately detecting and grading esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2246–2249. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, Townsend WF, Almagro UA, Komorowski RA, Choi H, Shaker R. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects Barrett's metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:472–478. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dranoff JA, Angood PJ, Topazian M. Transnasal endoscopy for enteral feeding tube placement in critically ill patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2902–2904. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Keefe SJ, Foody W, Gill S. Transnasal endoscopic placement of feeding tubes in the intensive care unit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:349–354. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027005349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulling D, Bauerfeind P, Fried M. Transnasal versus transoral endoscopy for the placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:506–510. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardar R, Varis A, Bayrakci B, Akyildiz S, Kirazli T, Bor S. Relationship between history, laryngoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy for diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux in patients with typical GERD. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(1):187–191. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1748-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan K, Liu G, Miller L, Ma C, Xu W, Schlachta CM, Darling G. Lack of correlation between a self-administered subjective GERD questionnaire and pathologic GERD diagnosed by 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(3):427–436. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]