Abstract

Effective management of healing and remodelling after myocardial infarction is an important problem in modern cardiology practice. We have recently shown that the level of infarct anisotropy is a critical determinant of heart function following a large anterior infarction, which suggests that therapeutic gains may be realized by controlling infarct anisotropy. However, factors regulating infarct anisotropy are not well understood. Mechanical, structural and chemical guidance cues have all been shown to regulate alignment of fibroblasts and collagen in vitro, and prior studies have proposed that each of these cues could regulate anisotropy of infarct scar tissue, but understanding of fibroblast behaviour in the complex environment of a healing infarct is lacking. We developed an agent-based model of infarct healing that accounted for the combined influence of these cues on fibroblast alignment, collagen deposition and collagen remodelling. We pooled published experimental data from several sources in order to determine parameter values, then used the model to test the importance of each cue for predicting collagen alignment measurements from a set of recent cryoinfarction experiments. We found that although chemokine gradients and pre-existing matrix structures had important effects on collagen organization, a response of fibroblasts to mechanical cues was critical for correctly predicting collagen alignment in infarct scar. Many proposed therapies for myocardial infarction, such as injection of cells or polymers, alter the mechanics of the infarct region. Our modelling results suggest that such therapies could change the anisotropy of the healing infarct, which could have important functional consequences. This model is therefore a potentially important tool for predicting how such interventions change healing outcomes.

Key points

After myocardial infarction, fibroblasts infiltrate the necrotic myocardium, deposit collagen, and remodel collagen, forming scar tissue.

Mechanical, structural, and chemical guidance cues have all been shown to regulate alignment of fibroblasts and collagen in vitro.

We developed a computational model of infarct healing with parameters closely tied to published data, ran simulations with different combinations of guidance cues, and successfully predicted measured collagen structures in rat infarct scars.

We determined that a mechanical guidance cue was the most important determinant of collagen alignment in healing myocardial infarcts.

Since anisotropy of infarct scar tissue is an important determinant of cardiac function, our model represents a potentially powerful tool for testing the effects of post-infarction therapies on scar anisotropy and designing new therapies that modulate infarct healing by controlling the mechanical stimuli acting on the infarct region or the response of fibroblasts to those stimuli.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 600,000 Americans experience a new myocardial infarction and 300,000 Americans experience a recurrent infarction (Lloyd-Jones et al. 2010). Most patients survive the initial event, making management of post-infarction healing and remodelling a high priority (Lloyd-Jones et al. 2010). Current revascularization procedures and pharmacological therapies seek to limit infarct extension, infarct expansion and adverse remodelling of remote myocardium (Sutton & Sharpe, 2000). Additionally, researchers are investigating regenerative therapies that may one day be able to restore contractile function to the infarct region (Forrester et al. 2003). These treatments are all motivated, at least in part, by the understanding that mechanical dysfunction is a key driver of the progression toward heart failure.

Treatments intended to reduce mechanical dysfunction of the heart or regenerate myocardium may be improved by controlling the anisotropy of infarct tissue. Anisotropy is an important feature of normal myocardium (Costa et al. 2001), which led us to study its importance in healing infarcts. We have recently shown that the level of infarct anisotropy is a critical determinant of heart function following a large anterior infarction (Fomovsky et al. 2011). However, factors regulating infarct anisotropy are not well understood. Mechanical, structural and chemical environmental cues have all been shown to regulate alignment of fibroblasts and collagen in vitro (Dickinson et al. 1994; Lee et al. 2008; Melvin et al. 2011), but understanding of fibroblast behaviour in the complex environment of a healing infarct is lacking. A better understanding of how fibroblasts integrate these cues as they deposit and remodel extracellular matrix in a healing infarct is needed in order to develop interventions that modify infarct scar anisotropy for therapeutic benefit.

Fibroblasts are the cell type primarily responsible for creating the microstructure, that is the density, orientation, thickness and crosslinking of collagen fibre bundles, that explains the mechanical properties of infarct scar tissue (Sacks, 2003; Souders et al. 2009). Fibroblasts assemble collagen fibres, secrete proteolytic and crosslinking enzymes, and apply traction forces that physically deform collagen fibre networks (Thomopoulos et al. 2005; Kadler et al. 2008). Fibroblasts can deposit collagen fibres oriented along their long axis and rotate nearby collagen fibres toward co-alignment with their long axis (Petroll et al. 2003; Canty et al. 2004). Consequently, any cue for fibroblast alignment may cause collagen alignment. In vitro studies have shown that fibroblasts align in response to uniaxial stretch (Neidlinger-Wilke et al. 2001; Pang et al. 2011), micropatterned ridges or aligned fibres (Dickinson et al. 1994; Wang et al. 2003), and chemokine gradients (Knapp et al. 1999; Melvin et al. 2011). These environmental guidance cues have been shown to cause fibroblasts to deposit anisotropic extracellular matrices or remodel isotropic matrices into anisotropic matrices (Wang et al. 2003; Thomopoulos et al. 2005).

Several studies have reported differing anisotropic properties of infarcts (Whittaker et al. 1989; Gupta et al. 1994; Holmes et al. 1997; Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010). It is difficult to make inferences about the determinants of infarct scar anisotropy due to the many variables that change from study to study, such as animal model, infarct location, infarct size and infarct shape, but there is some evidence supporting a role for chemical, structural and mechanical cues. In a computational model of skin wound healing, McDougall et al. (2006) showed that wound geometry can regulate collagen alignment by determining the spatial pattern of chemokine gradients. Zimmerman et al. (2000) studied the development of collagen alignment in healing pig infarcts and concluded that the initial matrix alignment in native myocardium determines the alignment of collagen in replacement scar. Recently, we performed a cryoinfarction study that independently varied the location and shape of infarcts in rats and found that infarct scar collagen alignment was correlated with the deformation pattern of the infarct, which depended on infarct location but not shape (Fomovsky et al. 2012). On the anterior, mid-ventricular wall of the heart, infarcts stretched primarily in the circumferential direction and developed scar tissue with circumferentially aligned collagen fibres. On the apex of the heart, infarcts stretched in the circumferential and longitudinal directions and developed scar tissue with a random collagen fibre orientation. This suggested that mechanical deformations regulate collagen alignment in infarct scar.

In view of the experimental evidence suggesting a role for mechanical, structural and chemical cues in determining the structural properties of healing infarcts and our limited insight into how fibroblasts integrate and respond to combinations of these cues, we developed an agent-based model of infarct healing in order to test hypotheses about how environmental cues guide fibroblasts to align collagen in healing infarcts. Agent-based modelling is well-suited to addressing problems of this kind, which investigate how the behaviours of individual agents within a system give rise to emergent properties of the whole system (Simpson et al. 2007; Chavali et al. 2008; Groh & Wagner, 2011). The work presented in this paper was primarily inspired by the dermal wound healing model published by McDougall et al. (2006). Our strategy was to build an agent-based model that incorporated experimentally measured fibroblast behaviours, environmental conditions and parameter values in order to predict the structural properties of the collagen matrix formed during infarct healing. We then independently perturbed the mechanical, structural and chemical guidance cues in the model and determined the importance of each cue for predicting measured collagen fibre structures in healing infarcts. Understanding the role of each cue is important for predicting how therapies that intentionally or unintentionally modify one or some combination of these cues will affect infarct scar structure and cardiac function.

Methods

Model description

Model space and matrix structure

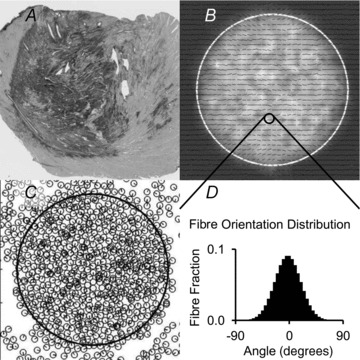

The agent-based model of infarct healing represented a midwall section of myocardium parallel to the epicardial surface as a two-dimensional rectangular space (Fig. 1A and B). This space was divided into 2.5 μm × 2.5 μm squares or patches. At each patch, a collagen fibre angle distribution and a non-collagen fibre angle distribution defined the local tissue structure (Fig. 1D). The non-collagen fibre angle distribution represented all components of myocardium that were neither collagen nor fibroblasts. (Since normal myocardium is highly aligned, we considered it important to capture the influence of the entire structure, not just the collagen fibres, on fibroblast alignment.) Fibre angles were divided into 5 deg bins ranging from −90 to +90 deg. The initial fibre angle distributions were prescribed to match the structure of normal myocardium. The area within a circle or ellipse centred in the space defined the infarct region. Remodelling of collagen fibre angle distributions via degradation, deposition and rotation was allowed throughout the model space. Remodelling of non-collagen fibre angle distributions was prohibited except for degradation within the infarct, which gradually eroded the influence of the non-collagen structure on fibroblast alignment.

Figure 1. Overview of the agent-based model of infarct healing.

A, histological section of a cryoinfarct scar after 3 weeks of healing, showing picrosirius red stained collagen fibres (dark tissue). B, example of a model result simulating the cryoinfarction experiment. Greyscale indicates collagen density and dashes indicate collagen fibre orientation. C, example of fibroblast agents that have infiltrated the infarct region by migrating and proliferating. D, example of local fibre orientation histogram. Each dash depicted in B indicates the mean angle and mean vector length (strength of alignment) of the local fibre orientation distribution.

Inflammation

The concentration profile of a single, generic chemokine represented the milieu of cytokines and chemokines released by necrotic myocytes, inflammatory cells, and fibroblasts within the infarct. A two-dimensional, steady state, reaction–diffusion equation was solved using the partial differential equation solver in Matlab (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The infarct geometry was centred in a rectangular domain 10 times the size of the infarct in order to approximate diffusion into an infinite space. Concentration was set to zero at the domain boundary. Chemokine degradation was assumed to occur everywhere, while chemokine generation was restricted to the infarct region:

|

(1) |

where Dc is chemokine diffusion coefficient, Cc is chemokine concentration, kc,gen is chemokine generation rate coefficient, and kc,deg is chemokine degradation rate coefficient.

Chemokine concentration modulated the activation level of fibroblasts. In the agent-based model, the chemokine concentration at any location was found by linear interpolation of the discrete solution of the reaction–diffusion equation. Fibroblast migration speed, proliferation rate, collagen deposition rate, and collagen degradation rate varied linearly with chemokine concentration between minimum and maximum values representing quiescent and activated fibroblast behaviour:

| (2) |

where Pi is ith rate parameter (fibroblast migration speed, proliferation rate, collagen deposition rate, or collagen degradation rate),  is maximum rate (activated fibroblast),

is maximum rate (activated fibroblast),  is minimum rate (quiescent fibroblast), Cc,max is maximum chemokine concentration, Cc,min is minimum chemokine concentration and Cc is chemokine concentration.

is minimum rate (quiescent fibroblast), Cc,max is maximum chemokine concentration, Cc,min is minimum chemokine concentration and Cc is chemokine concentration.

Mechanics

Mechanical strain was modelled as a field variable. Strains in the remote myocardium were prescribed as −5% in both the circumferential and longitudinal directions, based on experimental measurements prior to infarction in open-chest rats (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010). Strains in the centre of the infarct were prescribed as either equibiaxial or uniaxial. For the equibiaxial case, strain was prescribed as 5% in both the circumferential and longitudinal directions in order to simulate the deformation pattern observed in cryoinfarcts located on the apex of the left ventricle in rats (Fomovsky et al. 2012). For the uniaxial case, strain was prescribed as 5% in the circumferential direction and 0% in the longitudinal direction in order to simulate the deformation pattern observed in cryoinfarcts located on the anterior, mid-ventricular wall (Fomovsky et al. 2012). Between the centre of the infarct and the remote myocardium, the strain profile was assumed to be mostly flat except for a relatively sharp transition at the infarct border, in agreement with systolic strains measured across the border zone of an acutely ischemic region in dog hearts (Gallagher et al. 1986; Mazhari et al. 2000). The strain field was modelled as a modified cumulative normal distribution centred at the infarct border with standard deviation σb equal to 8% of the characteristic diameter of the infarct, as motivated by the work of Gallagher et al. (1986):

|

(3) |

where (R, θ) are polar coordinates relative to the centre of the infarct, ɛi is ith strain component, ɛi,infarct is strain in the centre of the infarct, ɛi,remote is strain in the remote myocardium, Rb is radial position of infarct border, and σb is standard deviation describing the width of the strain transition at the infarct border.

Fibroblasts

Fibroblasts were represented as discs of 5 μm radius (Fig. 1C). Fibroblasts responded to local environmental signals according to rules based on experimental observations of fibroblast behaviour. Environmental signals were chemokine concentration, strain and fibre alignment. Behaviours were migration, mitosis, apoptosis, collagen fibre deposition, collagen fibre rotation and matrix degradation. Counters for each cell kept track of the time elapsed since the last cell division and the overall age of the cell. Fibroblasts could move anywhere within the model space, except they were not permitted to overlap. Fibroblast orientation was determined by the combined influence of the current cell orientation, local chemokine gradient, local strain anisotropy and local fibre alignment.

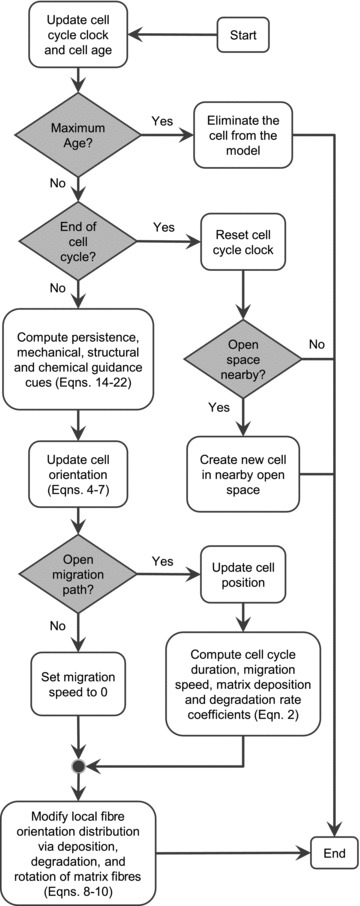

The model flowchart illustrates the fibroblast decision making process (Fig. 2). All model computations were performed using Matlab. The model was executed by stepping through time, and at each time point, stepping through all of the fibroblasts. At every time step, the order of stepping through the fibroblasts was randomized. Once a fibroblast reached its age limit, it was removed from the model. Once a fibroblast reached its cell cycle limit, a new fibroblast was created if there was space available adjacent to the original fibroblast. Once a fibroblast updated its direction, it migrated for a time step if there were no cells blocking its path. A fibroblast would then remodel the matrix located within its boundary by degrading matrix fibres, depositing collagen fibres, and rotating collagen fibres.

Figure 2. Fibroblast decision making flowchart.

At every time step, every fibroblast executes these operations and decisions.

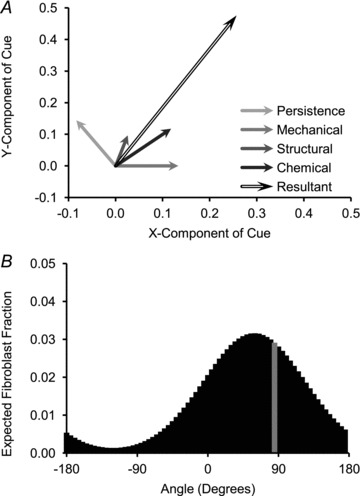

Fibroblast orientation was determined probabilistically, based on the strength of the local guidance cues: strain anisotropy (mechanical cue), fibre alignment (structural cue), chemokine gradient (chemical cue) and current fibroblast orientation (persistence cue). Each cue was represented as a vector  that could have magnitude ranging from 0 to some upper bound Mi equal to the maximum possible value in the model. These vectors were calculated by integrating each guidance cue over the surface of the cell, as explained in the Appendix. Each vector was normalized by Mi, weighted by a factor Wi, which prescribed the relative sensitivity of fibroblasts to each cue (eqn (4)), and then averaged to obtain a resultant vector

that could have magnitude ranging from 0 to some upper bound Mi equal to the maximum possible value in the model. These vectors were calculated by integrating each guidance cue over the surface of the cell, as explained in the Appendix. Each vector was normalized by Mi, weighted by a factor Wi, which prescribed the relative sensitivity of fibroblasts to each cue (eqn (4)), and then averaged to obtain a resultant vector  (eqn (5); Fig. 3A). Note, since strain and fibre direction are both axial cues (i.e. both 0 degrees and 180 degrees represent the direction of circumferential strain or a circumferentially oriented fibre), it was necessary to consider cases where the mechanical cue vector and structural cue vector were rotated 180 degrees, and then choose the resultant vector with the largest magnitude. The angle and magnitude of the resultant vector then defined the shape of a wrapped normal distribution, which for directional data is analogous to a Gaussian probability density function (eqns (6) and (7); Fig. 3B). Fibroblast orientation was determined by taking a random sample from a large array of angles representative of the wrapped normal distribution. This overall formulation ensured that each individual cue could cause a high degree of fibroblast alignment, that the strength of fibroblast alignment approaches a limit as cues are added in parallel, and that no combination of cues could cause perfect fibroblast alignment.

(eqn (5); Fig. 3A). Note, since strain and fibre direction are both axial cues (i.e. both 0 degrees and 180 degrees represent the direction of circumferential strain or a circumferentially oriented fibre), it was necessary to consider cases where the mechanical cue vector and structural cue vector were rotated 180 degrees, and then choose the resultant vector with the largest magnitude. The angle and magnitude of the resultant vector then defined the shape of a wrapped normal distribution, which for directional data is analogous to a Gaussian probability density function (eqns (6) and (7); Fig. 3B). Fibroblast orientation was determined by taking a random sample from a large array of angles representative of the wrapped normal distribution. This overall formulation ensured that each individual cue could cause a high degree of fibroblast alignment, that the strength of fibroblast alignment approaches a limit as cues are added in parallel, and that no combination of cues could cause perfect fibroblast alignment.

Figure 3. Method of determining fibroblast orientation.

A, each guidance cue was represented as a vector. The vectors were normalized, weighted and averaged in order to compute a resultant vector representing the combined influence of all of the cues on the fibroblast orientation. B, the magnitude and orientation of the resultant vector defined the shape of a wrapped normal distribution. The new fibroblast orientation (indicated by the grey bar in the histogram) was chosen by taking a random sample from a set of angles representing this distribution.

| (4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

| (7) |

where  is un-weighted, un-normalized cue vector, Mi is normalization factor,

is un-weighted, un-normalized cue vector, Mi is normalization factor,  is weighted and normalized cue vector, Wi is weight factor,

is weighted and normalized cue vector, Wi is weight factor,  is resultant vector, α is persistence tuning factor which ensures that

is resultant vector, α is persistence tuning factor which ensures that  , ϕwn is wrapped normal probability density function, θ is angle,

, ϕwn is wrapped normal probability density function, θ is angle,  is mean angle of

is mean angle of  , and σ is circular standard deviation.

, and σ is circular standard deviation.

Fibroblasts remodelled extracellular matrix located within their boundary by degrading fibres, depositing fibres, and rotating fibres. Fibroblasts degraded collagen fibres at a rate determined by the local collagen concentration and local chemokine concentration (eqn (8)). Fibroblasts deposited collagen fibres aligned with the current cell orientation at a rate determined by the local chemokine concentration (eqn (8)). Fibroblasts rotated collagen fibres toward parallel (or anti-parallel if closer) alignment with the current cell orientation at a rate that decreased as fibres approached co-alignment with the cell (eqn (9); McDougall et al. 2006). Degradation of non-collagen fibres was the same as degradation of collagen fibres, except only permitted in the infarct region (eqn (10)). Deposition and rotation of non-collagen fibres were prohibited.

| (8) |

|

(9) |

| (10) |

where Ncf is number of collagen fibres located within the cell boundary, t is time,  is collagen fibre generation rate coefficient, Cc is chemokine concentration, β = 14000 fibers/μm2 is the estimated maximum number of collagen fibers per unit area, Rcell is the radius of an individual fibroblast, δ is delta function indicating collagen fibres are deposited only aligned with the cell orientation,

is collagen fibre generation rate coefficient, Cc is chemokine concentration, β = 14000 fibers/μm2 is the estimated maximum number of collagen fibers per unit area, Rcell is the radius of an individual fibroblast, δ is delta function indicating collagen fibres are deposited only aligned with the cell orientation,  is current cell orientation, kcf,deg is collagen fibre degradation rate coefficient, Nncf is number of non-collagen fibres located within the cell boundary,

is current cell orientation, kcf,deg is collagen fibre degradation rate coefficient, Nncf is number of non-collagen fibres located within the cell boundary,  is non-collagen fibre degradation rate coefficient, θcf is collagen fibre direction, and kcf,rot is collagen fibre rotation rate coefficient.

is non-collagen fibre degradation rate coefficient, θcf is collagen fibre direction, and kcf,rot is collagen fibre rotation rate coefficient.

Scaling

The model simulated healing of a reduced scale infarct in order to shorten simulation time and decrease memory consumption, both of which were approximately proportional to model area. There were two important aspects of this model to consider when scaling: the diameter of the cells compared to the characteristic width of the chemokine gradient, and the number of patches covered by a single cell. First, for a fixed cell radius of 5 μm, we specified that at least 10 cells should fit along the width of the chemokine gradient peak. Using the dimensionless chemokine concentration profile, we calculated a minimum geometric scaling factor of 0.04, defined as the ratio of the model infarct diameter to the experimental infarct diameter. Second, we specified that at least 10 patches should fit within the area of the cell and calculated a patch spacing of 2.5 μm. Since we scaled the model geometrically, the fibroblast migration speed, which was the only transport parameter (a parameter with dimensions that are some combination of length and time) governing infiltration of fibroblasts into the infarct, was multiplied by a scaling factor equal to 0.2, defined as the ratio of the smallest dimension of the model infarct to the smallest dimension of the corresponding experimental infarct.

Parameter specification

The model contained a total of 25 parameters (Tables 1–7). The majority of these described the model geometry, environment and initial conditions, and they were therefore constrained by the conditions of the experiments to be simulated. Of the remaining 12 parameters, which determined the behaviour of the model, two parameters were estimated from literature data (fibroblast migration speed and proliferation rate), and five parameters were estimated by simulating published experiments and fitting model results to the published data, as described in more detail below. For the remaining five uncertain parameters, of which only four were important for the model results (kcf,rot,  , Wm and Wc), conservative estimates were chosen. For example, weight factors for the mechanical and chemical guidance cues were set equal to the structural cue weight factor, which was estimated from experimental data.

, Wm and Wc), conservative estimates were chosen. For example, weight factors for the mechanical and chemical guidance cues were set equal to the structural cue weight factor, which was estimated from experimental data.

Table 1.

Descriptive parameters: infarct dimensions

| Geometric Scaling factora | λg | 0.040 | |||

| Areab | Ai | 25 λg2 | mm2 | (Fomovsky et al. 2012) | |

| Circle | Ellipse | ||||

| Major radiusb | Rmaj | 2830 λg | 4000 λg | μm | (Fomovsky et al. 2012) |

| Minor radiusb | Rmin | 2830 λg | 2000 λg | μm | (Fomovsky et al. 2012) |

Geometric scaling factor explained in Methods ‘Scaling’.

Dimensions calculated for circle and 2:1 ellipse based on average cryoinfarct area reported by Fomovsky et al. (2012).

Table 7.

Behavioural parameters: fibroblast dynamics

| Infiltration scaling factori | λi | 0.2 | |||

| Time stepj | Δt | 0.5 | h | (Dickinson et al. 1994) | |

| Persistence tuning factork | α | 0.175 | (Dickinson et al. 1994) | ||

| Persistence cue weight factork | Wp | 0.333 | (Dickinson et al. 1994) | ||

| Structural cue weight factork | Ws | 0.167 | (Dickinson et al. 1994) | ||

| Mechanical cue weight factorl | Wm | 0.167 | |||

| Chemical cue weight factorl | Wc | 0.167 | |||

| Time to apoptosisn | Ta | 240 | h | ||

| Quiescent | Activated | ||||

| Time to mitosism | Tm | 240 | 24 | h | (Virag & Murry, 2003) |

| Migration speed | Scell | 1 λi | 10 λi | μm h−1 | (Dickinson et al. 1994) |

Infiltration scaling factor explained in Methods ‘Scaling’.

Model time steps greater than 0.5h failed to reproduce the migration data reported by Dickinson et al. (1994).

Calculation of the persistence tuning factor, persistence weight factor, and structural weight factor explained in Methods ‘Parameter specification’.

Mechanical and chemical weight factors assumed to be the same as the structural weight factor.

Time to mitosis in the infarct (activated state) calculated using the maximum count of BrdU positive cells reported in Virag & Murry (2003) and assuming S-phase takes 4 h. Also, in culture, first passage cardiac fibroblasts typically double in 24 h (unpublished observation). Time to mitosis in normal myocardium (quiescent state) assumed to be an order of magnitude slower than in the infarct.

Time to apoptosis chosen to ensure steady turnover of cells in normal myocardium.

Table 2.

Descriptive parameters: fibroblast size and initial concentration (normal myocardium)

| Radiusc | Rcell | 5 | μm | (Camelliti et al. 2005) |

| Area fraction | Ff | 0.25 | (Vliegen et al. 1991) |

Radius of simplified, disk-shaped fibroblast calculated from fibroblast area estimated from images in Camelliti et al. (2005).

Table 3.

Descriptive parameters: initial fibre structure (normal myocardium)

| Collagen fibre area fraction | Fcf | 0.03 | (Weber, 1989) | ||

| Non-collagen fibre area fraction | Fncf | 0.72 | (Vliegen et al. 1991) | ||

| Mean vector length | MVL | 0.75 | (unpublished observation) | ||

| Epicardium | Mid-depth | Endocardium | |||

| Mean angle | MA | –60 deg | 0 deg | 60 deg | (Omens et al. 1993) |

Table 4.

Descriptive parameters: strain field

| Border zone strain transition widthd | σb | 0.08 ✓(4RmajRmin) | (Gallagher et al. 1986) | ||

| Normal | Apical infarct | Anterior infarct | |||

| Circumferential strain | ɛc | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | (Fomovsky et al. 2012) |

| Longitudinal strain | ɛl | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0 | (Fomovsky et al. 2012) |

The width of the strain transition was about 8% of the width of the infarcts studied by Gallagher et al. (1986). We generalized the infarct width to be the average infarct diameter =✓(4RmajRmin).

Table 5.

Descriptive parameters: chemokine concentration field

| Diffusion coefficient | Dc | 100 λg2 | μm2 s−1 | (Safford et al. 1978) |

| Degradation rate coefficient | kc,deg | 0.001 | s−1 | (Bailón-Plaza & van der Meulen, 2001) |

| Generation rate coefficiente | kc,gen | 0.01 | nm s−1 |

The generation rate coefficient is an arbitrary value. It determines the magnitude but not the shape of the chemokine concentration profile. Its value is not important since calculations involving the chemokine concentration are normalized.

Table 6.

Behavioural parameters: fibre remodelling

| Quiescent | Activated | ||||

| Collagen degradation rate coefficientf | kcf,deg | 2.5E-4 | 2.5E-3 | h−1 | (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010) |

| Collagen generation rate coefficientf | kcf,gen | 7.5E-4 | 7.3E-2 | % area h−1 | (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010) |

| Collagen fibre rotation rate coefficientg | kcf,rot | 5 | 5 | deg h−1 | |

| Non-collagen degradation rate coefficienth | kncf,deg | 2.5E-3 | h−1 |

Calculation of the collagen degradation and generation rates in the infarct is explained in Methods ‘Parameter specification’. The degradation rate in normal myocardium (quiescent state) was assumed to be an order of magnitude slower than in the infarct (activated state). The collagen generation rate in normal myocardium was calculated to ensure a steady collagen area fraction of 0.03.

Collagen rotation rate coefficient approximated from observations of fibroblast-mediated remodelling of collagen gels.

Non-collagen degradation rate assumed to be the same as the collagen degradation rate.

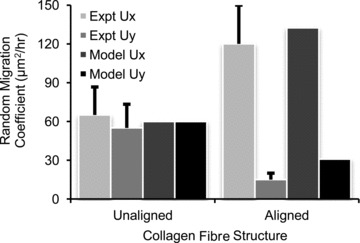

The persistence cue weight factor Wp, structural cue weight factor Ws, and persistence tuning constant α were estimated by matching simulated migration behaviour to published measurements. Dickinson et al. (1994) measured the migration tracks of fibroblasts in collagen gels with low and high degrees of collagen fibre alignment, calculated mean squared displacement curves for each condition, fit the data to the persistent random walk model of cell migration, and reported random migration coefficients for x- and y-directed motion. We used our agent-based model to simulate 10,000 migration tracks of fibroblasts in unaligned or aligned collagen matrices, performed the same analysis described by Dickinson et al. and adjusted Wp, Ws and α to fit the random migration coefficients derived from the simulations to the published values.

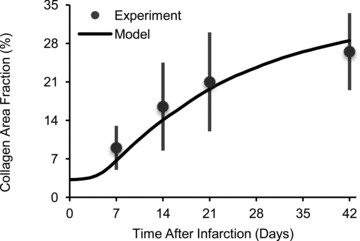

Collagen fibre degradation and deposition rate coefficients were estimated by fitting published measurements of collagen accumulation in healing infarcts. Fomovsky & Holmes (2010) measured collagen area fraction in rat ligation infarcts after 1, 2, 3 and 6 weeks of healing. We estimated collagen degradation and deposition rate coefficients by fitting the reported collagen accumulation time course to an ordinary differential equation accounting for zeroth order deposition and first order degradation of collagen (eqns (11)–(13)). We also included a time lag to account for the approximately 3 day delay before fibroblasts appear in large number at the site of the infarct. Finally, we verified that the fitted parameter values enabled the agent-based model to reproduce the experimental data.

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

where Fcf is collagen fibre area fraction, t is time, kcf,gen is collagen fibre generation rate coefficient, kcf,deg is collagen fibre degradation rate coefficient, Fcf,o is collagen fibre area fraction at time to, and Fcf,∞ is collagen fibre area fraction at steady state.

Simulations and analysis

Infarcts with different mechanical conditions (equibiaxial or uniaxial strain), and different shapes (circumferentially oriented ellipse, circle, longitudinally oriented ellipse) were modelled in order to cover the range of conditions investigated in the cryoinfarction study performed by our lab (Fomovsky et al. 2012). In order to test the effect of the mechanical guidance cue on the predicted collagen structure, a subset of simulations were run with the mechanosensing turned off by setting the weight factor for the mechanical cue equal to zero. In order to test the effect of the structural guidance cue on the predicted collagen structure, simulations were run with the fibres of the initial matrix structure oriented randomly, assigned a medium–high level of circumferential alignment equal to that of mid-thickness native myocardium, or perfectly aligned in the circumferential direction. In order to test the effect of rapid matrix degradation during the initial infarction, simulations were run with the initial matrix density set equal to or 1/10th the density of normal myocardium. Finally, in order to examine the balance between structural and mechanical cues at transmural locations other than mid-depth, 2D infarct layers were modelled with the mean fibre angle of the initial matrix structure varying from −60 to +60 deg relative to the circumferential axis, corresponding to the fibre angle variation observed through the thickness of normal myocardium.

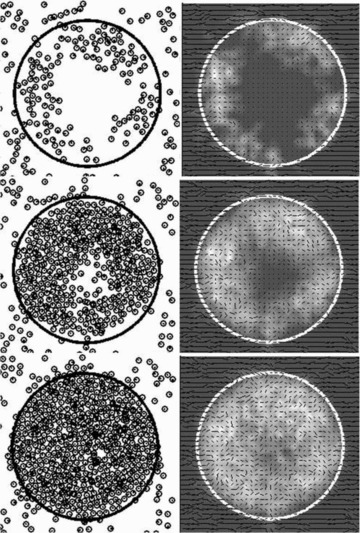

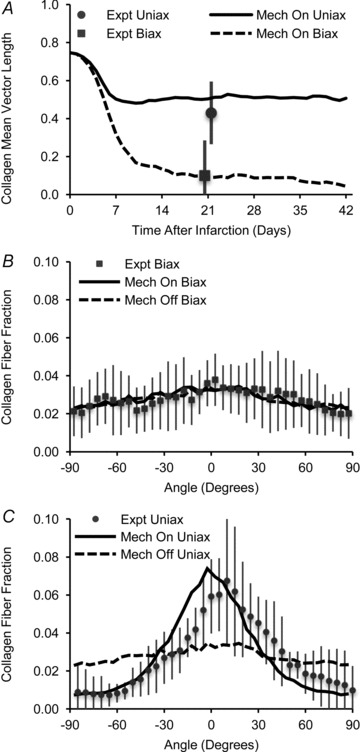

Models were run to simulate 6 weeks of healing (Fig. 4). Time courses of strength of collagen alignment, quantified as mean vector length, were compared among different model conditions. Predicted infarct collagen orientation histograms at the 3 week time point were compared to in vivo measurements taken 3 weeks after cryoinfarction in rats (Fomovsky et al. 2012). Predicted transmural profiles of mean collagen fibre angle and strength of collagen alignment were compared to in vivo measurements taken 3 weeks after ligation of an obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex coronary artery in pigs (Holmes, 1995, Holmes et al. 1997).

Figure 4. Time course of infarct healing.

Chemokine generated within the infarct stimulated fibroblast migration and proliferation (left), and upregulated collagen deposition (right). The illustrated time points are 4 (top), 7 (middle), and 10 (bottom) days after infarction.

Results

Parameter fitting

The persistence and structural cue weight factors Wp and Ws, the persistence tuning factor α, and the collagen degradation and generation rate constants kcf,deg and kcf,gen were determined by fitting published experimental data. Dickinson et al. (1994) computed migration coefficients for fibroblasts migrating in unaligned or highly aligned collagen gels. The simulated migration behaviour was determined by the ratios α/Wp and Ws/Wp, such that Wp could be arbitrarily chosen. The values α/Wp= 0.53 and Ws/Wp= 0.5 provided the best match to the published migration coefficients (Fig. 5). We previously measured collagen area fraction 1, 2, 3 and 6 weeks following coronary ligation in the rat (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010). The values  and kcf,gen= 0.073% area h−1 provided the best match to the published collagen accumulation time course (Fig. 6).

and kcf,gen= 0.073% area h−1 provided the best match to the published collagen accumulation time course (Fig. 6).

Figure 5. Fit of model to published fibroblast migration behaviour in collagen gels.

Dickinson et al. (1994) measured random migration coefficients for x-directed (Expt Ux) and y-directed (Expt Uy) motion of fibroblasts in collagen gels with unaligned or aligned collagen fibres. We obtained estimates of the model parameters Wp, Ws, and α by fitting simulated migration behaviour (Model Ux, Model Uy) to the published data.

Figure 6. Fit of model to published infarct collagen accumulation time course.

Fomovsky & Holmes (2010) measured collagen area fraction at several time points after creating ligation infarcts in rats (Experiment). We obtained estimates of the model parameters kcf,gen and kcf,deg by fitting a reaction ODE to the published data. Using the fitted parameter values, the agent-based model was able to reproduce the data (Model).

Chemical guidance cue

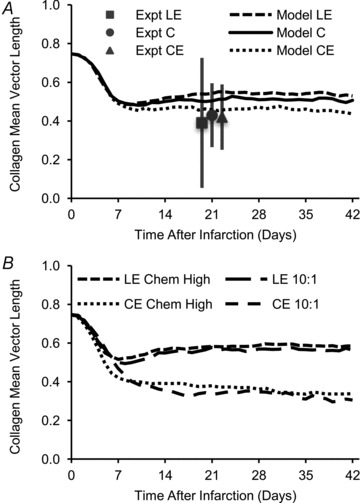

The chemical guidance cue had little effect on the predicted collagen alignment for the range of shapes examined in our cryoinfarct study, which was consistent with the experimental data. Model simulations were run with: longitudinally oriented elliptical infarcts, circular infarcts, or circumferentially oriented elliptical infarcts; circumferentially oriented initial matrix, as seen in normal myocardium at mid-thickness; and uniaxial strain in the circumferential direction, as measured in anterior, mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts. The different shapes created different spatial patterns of the chemokine gradient. However, the model predicted only small differences in collagen alignment that were well within the error of the experimental measurements from the mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts, consistent with the lack of an effect of infarct shape on collagen alignment in our cryoinfarct study (Fig. 7A). We then tested for conditions where the model would predict a measurable difference in the strength of collagen alignment between circumferentially and longitudinally oriented, elliptical infarcts. The infarcts would need an aspect ratio of at least 10:1 or the fibroblasts would need to be at least 4-fold more sensitive to the chemical cue in order for the orientation of the elliptical infarct to measurably affect the strength of collagen alignment (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Simulations of circular and elliptical infarcts (2:1 aspect ratio) experiencing uniaxial strain with initial matrix alignment as found in native myocardium.

A, the model predicted little difference in the strength of collagen alignment (quantified as the mean vector length of the average collagen fibre distribution) of a longitudinally oriented elliptical infarct (LE), circular infarct (C), and a circumferentially oriented elliptical infarct (CE). This was consistent with experimental data from our cryoinfarction study (Fomovsky et al. 2012). B, by increasing the aspect ratio of the elliptical infarcts to 10:1 or increasing the chemical cue weight factor Wc fourfold (Chem High), the model predicted a measurable effect of the orientation of the elliptical infarcts on the strength of collagen alignment.

Structural guidance cue

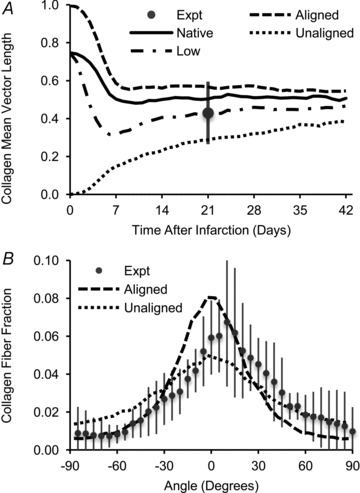

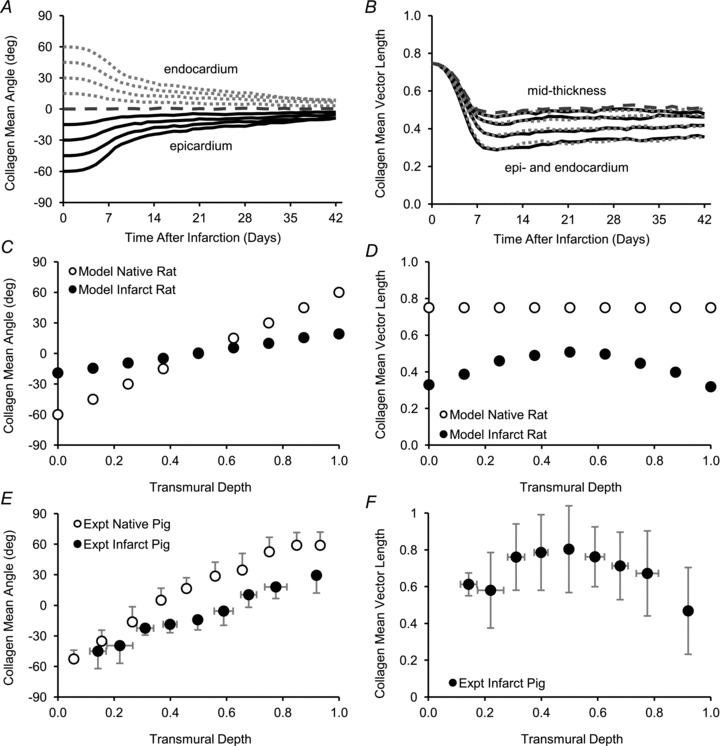

The initial matrix structure had little effect on the predicted collagen alignment after several weeks of healing, which was consistent with data from experimental models of infarction. First, model simulations were run with: circular infarcts; the initial matrix structure either perfectly aligned in the circumferential direction or unaligned; and uniaxial strain in the circumferential direction, as measured in circular, mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts. The initial matrix alignment had an effect on the alignment of deposited collagen at early times, but the predictions for the two different initial structures gradually converged over time (Fig. 8A). By 3 weeks, the predicted collagen fibre orientation histograms fell within a standard deviation of the experimental mean of the mid-ventricular cryoinfarct data, regardless of the strength of alignment of the initial matrix structure (Fig. 8B). Similarly, when the initial matrix density was decreased to 1/10th the density of normal myocardium, the model predicted lower alignment of collagen in the infarct at early times, but this difference became small after 3 weeks of healing (Fig. 8A). Finally, the model was used to simulate infarct healing at different transmural depths by prescribing different initial mean fibre angles ranging from −60 to +60 deg. Again, the predicted infarct collagen structures gradually converged over time (Fig. 9A and B). By 3 weeks, the predicted collagen fibre angle gradient through the thickness of the infarct was much smaller than the initial gradient (Fig. 9C), while the strength of collagen alignment was slightly higher at mid-thickness than at the epicardial and endocardial surfaces (Fig. 9D). These predictions were consistent with the transmural trends observed in pig infarcts (Fig. 9E and F), which also experienced transmurally uniform, uniaxial stretch in the circumferential direction.

Figure 8. Simulations of circular infarcts experiencing uniaxial strain with different initial matrix alignment or density.

A, the model predicted that infarcts with initial matrix structure that was either unaligned or perfectly aligned would have different collagen structures at early times, but gradually converge to the same degree of collagen alignment (Aligned vs Unaligned). Similarly, infarcts with initial matrix density that was either equal to or 1/10th the density of normal myocardium had different collagen alignment in the first week and then gradually converged thereafter (Native vs. Low). B, by 3 weeks, regardless of the strength of alignment of the initial matrix structure, the predicted collagen fibre orientation histograms fell within 1 standard deviation of the experimental mean for circular, mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts (Fomovsky et al. 2012).

Figure 9. Simulations of circular infarcts experiencing uniaxial strain with mean fibre orientations of the initial matrix varying from −60 deg at the epicardial surface (0% depth) to +60 deg at the endocardial surface (100% depth) to simulate a series of transmural layers in a healing infarct.

A, the model predicted that mean collagen fibre angles gradually converged on the circumferential direction. C, the model (with collagen turnover rates derived from rat ligation data) therefore predicted a flatter transmural fibre angle profile in 3-week-old infarcts than in healthy myocardium (Model Infarct Rat vs. Model Native Rat). E, a similar trend was present in transmural fibre angle profiles measured before and 3 weeks after infarction in pigs (Expt Native Pig vs. Expt Infarct Pig) (Holmes, 1995; Holmes et al. 1997). B, the model suggested that mean vector length would converge more slowly than mean fibre angle. D, after 3 weeks of simulated healing, the model predicted strongest alignment (highest mean vector length) at mid-depth, where the direction of stretch and the initial matrix orientation were identical, and weakest alignment at the surfaces, where initial matrix orientation differed most from the direction of stretch (Model Infarct Rat). F, a similar transmural trend in mean vector length was reported in pig infarcts 3 weeks after ligation (Expt Infarct Pig).

Mechanical guidance cue

A mechanical guidance cue was required to support long-term alignment of collagen in infarct scar, which was consistent with the experimental cryoinfarction data. Models were run with: circular infarcts; circumferentially oriented initial matrix; and either uniaxial strain in the circumferential direction or equibiaxial strain. For each mechanical condition, model simulations were run with mechanosensing turned on or off. With mechanosensing on, if the pattern of stretch was equibiaxial, the initially aligned matrix was replaced by randomly oriented collagen, whereas if the pattern of stretch in the infarct was uniaxial, scar formed with aligned collagen fibres (Fig. 10A). The predicted collagen fibre orientation histograms after 3 weeks of healing were consistent with those observed for apical cryoinfarcts that experienced biaxial stretch (Fig. 10B) and mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts that experienced uniaxial stretch (Fig. 10C). In contrast, when mechanosensing was turned off, although the model results for the case of equibiaxial stretch were unchanged (Fig. 10B), the model failed to reproduce the collagen fibre alignment seen in the uniaxially stretched cryoinfarcts (Fig. 10C).

Figure 10. Simulations of circular infarcts with uniaxial or equibiaxial strains and with initial matrix alignment as found in native myocardium.

A, the model predicted that long term alignment of collagen in a healing infarct required a uniaxial mechanical cue, which was consistent with experimental data from our cryoinfarction study (Expt Uniax vs. Expt Biax). B and C, at 3 weeks, with mechanosensing turned on (Mech On), the model predicted collagen fibre orientation histograms similar to those measured in cryoinfarcts experiencing biaxial or uniaxial strain. With mechanosensing turned off (Mech Off), the aligned collagen structure for the case of uniaxial strain could not be predicted.

Discussion

Prior studies have proposed that mechanical, structural, or chemical cues could regulate the anisotropy of infarct scar tissue. We developed an agent-based model that accounted for the combined influence of these cues on fibroblast alignment, collagen deposition and collagen remodelling. We pooled published experimental data from several sources in order to determine parameter values in the model (Tables 1–7), and then tested model predictions against collagen alignment measurements from a set of recent cryoinfarction experiments that independently varied infarct shape and pattern of stretch in a consistent animal model (Fomovsky et al. 2012). The model predicted collagen structures in very good agreement with the experimental measurements across all cryoinfarct groups. We then independently perturbed the mechanical, structural, and chemical cues in the model in order to determine how strongly each cue influenced the predicted collagen structure. Although chemokine gradients and pre-existing matrix structures influenced spatial and temporal patterns of collagen organization in certain situations, a mechanical cue was critical to reproducing the collagen alignment observed experimentally in healing infarcts.

Chemical guidance cue

McDougall et al. (2006) proposed that the pattern of collagen alignment in dermal wounds could be explained by alignment of fibroblasts in the direction of the chemical gradient established by chemokines generated within the wound. According to this hypothesis, differently shaped infarcts should have different chemokine gradient patterns and different patterns of collagen alignment. We used our model to simulate healing of a longitudinally oriented elliptical infarct, circular infarct and circumferentially oriented infarct, and found a negligible effect of infarct shape on the average collagen alignment (Fig. 7A). Although this finding was in contrast with the model results of McDougall et al., it was consistent with our cryoinfarction data. The model provides some insight as to why this is the case. The predicted chemokine concentration profile was mostly flat throughout the bulk of the infarct and decreased sharply at the infarct border. Consequently, the influence of the chemical cue on collagen fibre alignment was limited to the region near the infarct border where the steep concentration gradient greatly increased the strength of the chemical guidance cue. Only in model infarcts with very high aspect ratios (>10:1) did this border effect measurably influence the average collagen fibre alignment (Fig. 7B). Although we restricted this study only to elliptical infarcts, the results imply that chemokine gradients might explain some regional variation in the collagen structure of ligation infarcts, which tend to be more irregularly shaped than the cryoinfarcts of interest in this work.

Structural guidance cue

Zimmerman et al. (2000) proposed that the orientation of collagen fibres in healing infarcts could be explained by the orientation of the matrix surrounding native myocardium, some of which survives and acts as a template for alignment of fibroblasts and collagen during scar formation. We used our model to simulate healing of an infarct with an initial matrix structure that was either perfectly aligned or unaligned (random), and found that the influence of the initial matrix structure on the predicted collagen alignment faded over the time course of healing (Fig. 8). We also used our model to simulate healing of an infarct with mechanosensing turned off, and found that an initially aligned matrix structure alone was unable to support long-term collagen alignment (Fig. 10C). These results were consistent with our cryoinfarction experiments, which found that alignment of collagen fibres in infarct scar was only seen in infarcts that experienced uniaxial stretch. The model provides some insight as to why the initially aligned matrix structure failed to support long term collagen alignment in healing infarcts. In the model, the choice of fibroblast orientation had an element of randomness, which ensured that fibroblasts would not always orient perfectly in the direction of the initially aligned matrix fibres. Since fibroblasts deposited collagen fibres along and rotated collagen fibres toward their current orientation, the strength of alignment of the matrix was therefore reduced by the imperfectly aligned cells. Subsequently, fibroblasts would have an even lesser tendency to align with the initial structural cue. In other words, since fibroblasts can change the matrix structure, then it cannot be a stable guidance cue. Interestingly, we recently reported that collagen fibre distributions in scars that experienced biaxial stretch were random by 1 week after coronary ligation in the rat (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010), suggesting that our current model actually overestimates the true influence of pre-existing matrix on collagen fibre orientation in the developing scar. This could reflect the fact that some of the pre-existing matrix is degraded rapidly in the first hours following infarction (Takahashi et al. 1990). Consistent with this possibility, when we simulated infarcts with a lower initial matrix density, the model predicted a faster decrease in the strength of collagen alignment in the first few days after infarction (Fig. 8A). Alternatively, the weighting of structural cues could be too high in our current model. However, this seems less likely given the close agreement of experimental data with the predicted transmural trends of infarct collagen alignment, which depended on the magnitude of the structural cue weight factor (Fig. 9C–F).

Mechanical guidance cue

In our cryoinfarction study (Fomovsky et al. 2012), we found that the location of the infarct determined its pattern of deformation, and this deformation pattern was correlated with collagen fibre alignment. When we simulated healing of an infarct with mechanosensing turned on, we found that the mechanical environment (uniaxial or equibiaxial stretch) determined whether the healing infarct ultimately formed an aligned or disorganized structure (Fig. 10A). This result was consistent with the experimental cryoinfarct findings. Cryoinfarcts that experienced uniaxial stretch developed scars with collagen fibres aligned in the direction of stretch, while cryoinfarcts that experienced biaxial stretch developed scars with poorly aligned collagen fibres. When mechanosensing was turned off, the collagen alignment observed in the mid-ventricular cryoinfarcts could not be reproduced (Fig. 10C). The model provides some insight as to why the mechanical cue was the most important determinant of infarct collagen alignment. First, unlike the chemical cue, which has its influence spatially restricted to the infarct border where the chemokine gradient is highest, the mechanical cue has influence throughout the bulk of the infarct. Second, unlike the structural cue, which is unstable in the absence of any supporting cues, the mechanical cue is maintained by the external loads acting on the infarct. Indeed, infarct strains were shown to be fairly consistent for 6 weeks after coronary ligation in rats (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010).

Broader comparison to experimental data

Our primary source of comparison data in this paper was a set of rat cryoinfarction experiments performed in our laboratory. Although the cryoinjury model of infarction has many advantages, such as enabling control of infarct shape and location, tissue damage caused by freezing is not identical to damage caused by ischaemia, and there may be important differences in the subsequent scar formation process. We therefore performed additional comparisons to published data on collagen fibre structure in healing myocardial infarcts induced by coronary ligation. Broadly, the published data agree well with our model predictions. For example, infarcts resulting from ligation of an obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex coronary artery in pigs stretched circumferentially and developed circumferentially aligned collagen fibres (Holmes et al. 1997), while infarcts resulting from left coronary artery ligation in rats stretched biaxially and developed randomly aligned collagen fibres (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010). When reviewing published data on infarct collagen fibre structure, we recognized that as in our prior studies in pigs (Holmes et al. 1997), multiple investigators have reported less transmural variation of the collagen fibre orientation in healing infarcts than typically observed in normal myocardium (Whittaker et al. 1989; Omens et al. 1997). We therefore simulated infarct healing at different transmural depths and compared the predicted transmural profiles of mean fibre angle and mean vector length to our experimental data obtained from 3 week old ligation infarcts in pigs (Fig. 9), in which the initial muscle fibre angle varies from –60 to +60 deg but the infarct experiences uniaxial stretch of similar magnitude at all transmural depths. Despite the fact that many of the model parameter values were derived from experimental studies of rats, the model reproduced the trends seen in the pig data strikingly well and provided an explanation for the observed structures. At mid-depth, where the mean angle of the initial matrix structure and the direction of greatest stretch coincided, the healing infarcts developed highly aligned collagen oriented in the circumferential direction. At the endocardium and epicardium, where the initial matrix structure and mechanical environment provided conflicting cues, the effect of the initial matrix structure gradually faded, so that by 3 weeks the mean collagen fibre angles in these layers were closer to circumferential but the strength of alignment was still lower than at mid-depth. The findings of these ligation infarction studies are consistent with the model predictions and the cryoinfarction study, and support the generality of the conclusions drawn from the model.

Model innovations

The agent-based model presented in this work is a significant advance in the use of computational modelling to understand infarct healing. Previous models of infarct healing have used systems of ordinary differential equations to predict the dynamics of fibroblast, macrophage, chemokine and collagen accumulation in the infarct (Wang et al. 2010; Jin et al. 2011). More general wound healing models have used agent-based or continuum methods to predict the spatial and temporal evolution of cell populations, chemokines and extracellular matrix components (Mi et al. 2007; Javierre et al. 2009). Several of these models were developed to predict structural remodelling of the extracellular matrix, which motivated our modelling approach (McDougall et al. 2006; Ohsumi et al. 2008; Groh & Wagner, 2011). However, our model is the first to include the combined influence of mechanical, structural, and chemical guidance cues on fibroblast behaviour to predict collagen fibre alignment in scar tissue formed after myocardial infarction. Furthermore, we carefully tied behaviours and parameter values in our model to experimental observations, which allowed the model predictions to be quantitatively compared to in vivo measurements.

Model limitations

Several limitations of the model highlight features of infarct healing that are currently poorly understood and merit further study. First, our model represents a 2D slice through the circumferential–longitudinal plane of the myocardium. Consequently, in the model, fibroblasts can only enter the infarct by migrating in this plane, whereas in vivo, cells might also infiltrate the infarct from the epicardial and endocardial borders, originate from circulating cells that enter the infarct through the vasculature, or even survive the initial infarction. Our model predicts a time course of cell infiltration that is similar to in vivo observations (1–2 weeks for cells to reach the core of the necrotic region) (Fig. 4), which generally supports our approach, but additional studies on the detailed pattern of fibroblast migration into the infarct are needed. Furthermore, the 2D model simplifies the 3D nature of strain and fibre angle distributions seen in normal myocardium. While we investigated the effect of the transmural gradient of initial fibre angle (Fig. 9), transmural gradients in strain were not considered since they have been shown to become small within minutes after infarction (Villarreal et al. 1991) and remain small through at least 3 weeks of healing (Holmes et al. 1994). Consequently, we treated the infarct as a stack of 2D layers, each with a different initial matrix structure, but all with the same mechanical environment.

Second, our model represents infarct strains as static field variables. In reality, the balance between increased stresses due to LV dilatation and infarct thinning, and increased stiffness due to collagen deposition will determine how infarct strains evolve over time. Our model assumption was based on the fact that we saw little change in strain magnitudes over time in our previous study of healing rat infarcts (Fomovsky & Holmes, 2010).

Third, our model represents the chemokine concentration as a static field variable. In reality, many chemokines are released at the site of an infarct in a complex spatial and temporal pattern. Since it is not fully understood how all of these factors regulate fibroblast behaviour, we chose to model a single generic chemokine, giving it the effect of ‘activating’ fibroblast proliferation, migration and collagen remodelling. Although representing the exact spatiotemporal profile of chemokine release is likely to be important for making predictions about infarct healing at early time points, we do not expect it to be important after fibroblasts have uniformly populated the infarct.

Fourth, our model represents the matrix deforming traction forces that fibroblasts generate as rotation of collagen fibres toward co-alignment with the cell. The rotation rate coefficient, which is an important determinant of the predicted time course of collagen alignment, is an unconstrained parameter in the model. We conservatively chose a value of only a few degrees per hour, and found good agreement of the model with experimental data after 3 weeks of healing, but data at additional time points will be needed in order to better establish a value for the rotation rate coefficient.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that although chemokine gradients and pre-existing matrix structures have important effects on collagen organization, a mechanical cue is critical for the development of collagen alignment in infarct scar. It is important to understand the effects of these cues if interventions are to be designed that seek to preserve cardiac function after infarction by controlling the anisotropy of infarct scar. Furthermore, many proposed therapies for myocardial infarction, such as injection of cells or polymers (Christman et al. 2004), implantation of materials for structural support (Kelley et al. 1999), and peri-infarct pacing (Chung et al. 2010), alter the mechanics of the infarct region. Our modelling results suggest that such therapies could unintentionally change the anisotropy of the healing infarct, which could have important functional consequences. This model represents a potentially powerful tool for predicting how such interventions change healing outcomes. This work is also relevant for tissue engineering and for repair of any tissue where anisotropy is an important determinant of tissue function, such as tendons and ligaments.

Appendix. Calculation of guidance cue vectors

In order to compute the vector for the chemical cue, the chemokine concentration at the cell boundary was multiplied by the unit outward normal vector, and this scaled vector was averaged over the cell boundary. The result was a vector pointing in the direction of greatest chemokine concentration at the cell boundary with magnitude determined by the steepness of the local chemokine gradient:

|

(14) |

where  is chemical guidance cue vector, Cc is chemokine concentration,

is chemical guidance cue vector, Cc is chemokine concentration,  is unit outward normal vector from cell surface, and Rcell is cell radius.

is unit outward normal vector from cell surface, and Rcell is cell radius.

In order to compute the vector for the mechanical cue, the normal strain at the cell boundary was multiplied by the unit outward normal vector with doubled angle, and this scaled vector was averaged over the cell boundary. The 2θ transform was performed because tension on the cell is an axial cue, rather than a directional cue, so anti-parallel strains should sum instead of cancelling. The result was transformed from 2θ space back to θ space by halving the angle of the computed vector. The result was a vector pointing in the direction of greatest tensile strain across the cell with magnitude determined by the degree of anisotropy of the local strain field:

| (15) |

|

(16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

where ɛn is strain normal to cell surface,  is unit outward normal vector from cell surface,

is unit outward normal vector from cell surface,  is strain tensor,

is strain tensor,  is mechanical guidance cue vector in 2θ space,

is mechanical guidance cue vector in 2θ space,  is cell radius, θm is mechanical guidance cue direction in θ space, and

is cell radius, θm is mechanical guidance cue direction in θ space, and  is mechanical guidance cue vector in θ space.

is mechanical guidance cue vector in θ space.

In order to compute the vector for the structural cue, the mean vector length and mean angle of the total population of collagen and non-collagen fibres located within the cell boundary were calculated. Again, the 2θ transform was performed because fibre direction is an axial cue, rather than a directional cue. The result was a vector pointing in the mean direction of the local matrix fibres with magnitude determined by the degree of co-alignment of the fibres:

|

(19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

where  is structural guidance cue vector in 2θ space, Nf is number of fibres located within the cell boundary,

is structural guidance cue vector in 2θ space, Nf is number of fibres located within the cell boundary,  is unit vector, θs is structural guidance cue direction in θ space, and

is unit vector, θs is structural guidance cue direction in θ space, and  is structural guidance cue vector in θ space.

is structural guidance cue vector in θ space.

In order to compute the vector for the persistence cue, the unit vector pointing along the cell orientation was multiplied by the cell speed:

| (22) |

where  is persistence cue vector,

is persistence cue vector,  is current cell migration speed,

is current cell migration speed,  is unit vector, and

is unit vector, and  is current cell orientation.

is current cell orientation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gregory Fomovsky, Ph.D. for helpful discussions and for providing the experimental cryoinfarct data used for comparisons in this paper. Funding was provided by an American Heart Association Pre-doctoral Fellowship (A.D.R.) and National Institutes of Health NHLBI RO1 HL-075639 (J.W.H.).

Author contributions

The work was performed in the Cardiac Biomechanics Group laboratory at the University of Virginia. The authors collaborated on all aspects of the study.

References

- Bailón-Plaza A, van der Meulen MCH. A mathematical framework to study the effects of growth factor influences on fracture healing. J Theor Biol. 2001;212:191–209. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty EG, Lu Y, Meadows RS, Shaw MK, Holmes DF, Kadler KE. Coalignment of plasma membrane channels and protrusions (fibripositors) specifies the parallelism of tendon. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:553–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavali AK, Gianchandani EP, Tung KS, Lawrence MB, Peirce SM, Papin JA. Characterizing emergent properties of immunological systems with multi-cellular rule-based computational modeling. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman KL, Fok HH, Sievers RE, Fang Q, Lee RJ. Fibrin glue alone and skeletal myoblasts in a fibrin scaffold preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:403–409. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Dan D, Solomon S, Bank A, Pastore J, Iyer A, Berger R, Franklin J, Jones G, Machado C, Stolen C. Effect of peri-infarct pacing early after myocardial infarction: results of the prevention of myocardial enlargement and dilatation post myocardial infarction study. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:650–658. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.945881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa KD, Holmes JW, McCulloch AD. Modelling cardiac mechanical properties in three dimensions. Philos Trans Roy Soc A Math Phys Eng. 2001;359:1233–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RB, Guido S, Tranquillo RT. Biased cell migration of fibroblasts exhibiting contact guidance in oriented collagen gels. Ann Biomed Eng. 1994;22:342–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02368241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomovsky GM, Holmes JW. Evolution of scar structure, mechanics, and ventricular function after myocardial infarction in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H221–H228. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00495.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomovsky GM, Macadangdang JR, Ailawadi G, Holmes JW. Model-based design of mechanical therapies for myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Trans Res. 2011;4:82–91. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9241-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomovsky GM, Rouillard AD, Holmes JW. Regional mechanics determine collagen fiber structure in healing myocardial infarcts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester JS, Price MJ, Makkar RR. Stem cell repair of infarcted myocardium: an overview for clinicians. Circulation. 2003;108:1139–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085305.82019.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KP, Gerren RA, Stirling MC, Choy M, Dysko RC, McManimon SP, Dunham WR. The distribution of functional impairment across the lateral border of acutely ischemic myocardium. Circ Res. 1986;58:570–583. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh A, Wagner M. Biased three-dimensional cell migration and collagen matrix modification. Math Biosci. 2011;231:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KB, Ratcliffe MB, Fallert MA, Edmunds LH, Bogen DK. Changes in passive mechanical stiffness of myocardial tissue with aneurysm formation. Circulation. 1994;89:2315–2326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JW. Remodeling, Deformation, and Tissue Structure in Healing Myocardial Infarcts. San Diego: University of California; 1995. (thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JW, Nuñez JA, Covell JW. Functional implications of myocardial scar structure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;272:H2123–H2130. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JW, Yamashita H, Waldman LK, Covell JW. Scar remodeling and transmural deformation after infarction in the pig. Circulation. 1994;90:411–420. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javierre E, Moreo P, Doblaré M, García-Aznar JM. Numerical modeling of a mechano-chemical theory for wound contraction analysis. Int J Solids Struct. 2009;46:3597–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Han H, Berger J, Dai Q, Lindsey ML. Combining experimental and mathematical modeling to reveal mechanisms of macrophage-dependent left ventricular remodeling. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG. Collagen fibrillogenesis: fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ST, Malekan R, Gorman JH, Jackson BM, Gorman RC, Suzuki Y, Plappert T, Bogen DK, Sutton MG, Edmunds LH. Restraining infarct expansion preserves left ventricular geometry and function after acute anteroapical infarction. Circulation. 1999;99:135–142. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DM, Helou EF, Tranquillo RT. A fibrin or collagen gel assay for tissue cell chemotaxis: assessment of fibroblast chemotaxis to GRGDSP. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:543–553. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Holmes JW, Costa KD. Remodeling of engineered tissue anisotropy in response to altered loading conditions. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:1322–1334. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhari R, Omens JH, Covell JW, McCulloch AD. Structural basis of regional dysfunction in acutely ischemic myocardium. Cardiovas Res. 2000;47:284–293. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall S, Dallon J, Sherratt J, Maini P. Fibroblast migration and collagen deposition during dermal wound healing: mathematical modelling and clinical implications. Philos Trans Roy Soc A Math Phys Eng. 2006;364:1385–1405. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2006.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin AT, Welf ES, Wang Y, Irvine DJ, Haugh JM. In chemotaxing fibroblasts, both high-fidelity and weakly biased cell movements track the localization of PI3K signaling. Biophys J. 2011;100:1893–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Q, Rivière B, Clermont G, Steed DL, Vodovotz Y. Agent-based model of inflammation and wound healing: insights into diabetic foot ulcer pathology and the role of transforming growth factor-β1. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:671–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidlinger-Wilke C, Grood ES, Wang JH-C, Brand RA, Claes L. Cell alignment is induced by cyclic changes in cell length: studies of cells grown in cyclically stretched substrates. J Orth Res. 2001;19:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi TK, Flaherty JE, Evans MC, Barocas VH. Three-dimensional simulation of anisotropic cell-driven collagen gel compaction. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2008;7:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s10237-007-0075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omens JH, MacKenna DA, McCulloch AD. Measurement of strain and analysis of stress in resting rat left ventricular myocardium. J Biomech. 1993;26:665–676. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90030-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omens JH, Miller TR, Covell JW. Relationship between passive tissue strain and collagen uncoiling during healing of infarcted myocardium. Cardiovas Res. 1997;33:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Wang X, Lee D, Greisler HP. Dynamic quantitative visualization of single cell alignment and migration and matrix remodeling in 3-D collagen hydrogels under mechanical force. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3776–3783. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroll WM, Ma L, Jester JV. Direct correlation of collagen matrix deformation with focal adhesion dynamics in living corneal fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1481–1491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MS. Incorporation of experimentally-derived fiber orientation into a structural constitutive model for planar collagenous tissues. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:280–287. doi: 10.1115/1.1544508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford RE, Bassingthwaighte EA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Diffusion of water in cat ventricular myocardium. J Gen Physiol. 1978;72:513–538. doi: 10.1085/jgp.72.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M, Merrifield A, Landman KA, Hughes BD. Simulating invasion with cellular automata: connecting cell-scale and population-scale properties. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2007;76:1–11. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.021918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souders CA, Bowers SLK, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res. 2009;105:1164–1176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MG, Sharpe N. Left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: pathophysiology and therapy. Circulation. 2000;101:2981–2988. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Barry AC, Factor SM. Collagen degradation in ischaemic rat hearts. Biochem J. 1990;265:233–241. doi: 10.1042/bj2650233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomopoulos S, Fomovsky GM, Holmes JW. The development of structural and mechanical anisotropy in fibroblast populated collagen gels. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:742–750. doi: 10.1115/1.1992525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal FJ, Lew WYW, Waldman LK, Covell JW. Transmural myocardial deformation in the ischemic canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1991;68:368–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virag JI, Murry CE. Myofibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation during murine myocardial infarct repair. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2433–2440. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63598-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliegen HW, van der Laarse A, Cornelisse CJ, Eulderink F. Myocardial changes in pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy: a study on tissue composition, polyploidization and multinucleation. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:488–494. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH-C, Jia F, Gilbert TW, Woo SL-Y. Cell orientation determines the alignment of cell-produced collagenous matrix. J Biomech. 2003;36:97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Han H-C, Yang JY, Lindsey ML, Jin Y. A conceptual cellular interaction model of left ventricular remodelling post-MI: dynamic network with exit-entry competition strategy. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT. Cardiac interstitium in health and disease: the fibrillar collagen network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:1637–1652. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker P, Boughner DR, Kloner RA. Analysis of healing after myocardial infarction using polarized light microscopy. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:879–893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]