Abstract

Studies of depressed psychiatric patients have shown that antidepressant efficacy can be increased by augmentation with omega-3 fatty acids (FAs). The purpose of this study was to determine whether omega-3 augmentation improves the response to sertraline in patients with major depression and documented coronary heart disease (CHD). One hundred twenty-two patients with major depression and CHD were given 50 mg/day of sertraline (Zoloft™) and randomized in double-blind fashion to 2g/day of omega-3 (Lovaza™) or to corn oil placebo capsules. Adherence to the medication regimen was 97% in both groups for both medications. The levels of omega-3 (percent DHA+EPA in red blood cells) were nearly identical between the groups at baseline; the level changed during the intervention phase in the omega-3 arm to the expected level, but it remained stable in the placebo arm. Neither weekly Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) scores (p = .38) nor pre-post BDI-II scores (p = .44) differed between the omega-3 and placebo groups. The rates of depression remission (BDI-II ≤ 8) and response (>50% reduction in BDI-II from baseline) were also nearly identical. In conclusion, this trial yielded no evidence that omega-3 augmentation increases the efficacy of sertraline for comorbid major depression in CHD. Whether higher doses of omega-3, longer treatment, or the use of omega-3 as a monotherapy can improve depression in patients with stable heart disease remains to be determined.

Depression is a well-established risk factor for cardiac morbidity and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).1–3 However, the underlying mechanisms for this increased risk are not well understood, and it is unknown whether treating depression will reduce this risk. Low dietary intake and low serum or red blood cell levels of omega-3 fatty acids (FAs) have been associated with depression in patients with4–6 and without CHD7–10, and with an increased risk for cardiac-related mortality11, 12, suggesting a possible link between depression and cardiac events. Two omega-3 FAs, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are concentrated at synapses in the human brain and are essential for neuronal functioning.11, 13, 14 There is evidence that eating foods or taking dietary supplements containing DHA and EPA may reduce the rate of sudden cardiac death in high risk patients15–18, and may improve depression or enhance the efficacy of antidepressants in depressed but otherwise medically well psychiatric patients.19

Small studies of otherwise medically well depressed psychiatric patients have found that augmentation of antidepressants with omega-3 FAs improves the efficacy of these drugs. Nemets and colleagues20 randomized 20 patients with a current major depressive episode who were already receiving an antidepressant, to receive either a placebo or two grams per day of EPA. Both groups remained on their previously-prescribed antidepressant throughout the trial. The mean reduction in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scores in the omega-3 group was 12.4 points, compared with 1.6 for the placebo group (p < 0.001).

Peet and Horrobin21 randomized 70 patients on conventional antidepressants to augmentation with a placebo or 1, 2, or 4 grams per day of the EPA form of omega-3. In an intention-to-treat analysis, patients receiving the lowest dose of EPA (1 g/d) improved significantly more on three measures of depression than did patients on placebo. Although both groups had moderately severe depression at baseline (mean HAM-D, 19.9 [EPA] vs. 20.3 [placebo]), the patients given EPA showed more improvement at 10 weeks on the HAM-D (−9.9) and the BDI (−12.5) than did those who were given a placebo (6.1 and 6.5, respectively; p< 0.001).

The purpose of this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was to determine whether omega-3 augmentation improves the efficacy of sertraline for comorbid major depression in documented CHD.

METHODS

Recruitment and Eligibility Screening

Patients were recruited from cardiology practices in the St. Louis area, and from cardiac diagnostic laboratories affiliated with Washington University School of Medicine or BJC Health Care, Inc. Patients were informed about the study by their physicians; by the study staff via a letter or personal contact; or by pamphlets and posters placed in cardiology offices, cardiac diagnostic laboratories, and other laboratories throughout the St. Louis area. A local TV newscast also mentioned the study in a feature on depression.

Patients who provided informed consent and who had CHD, as documented by significant coronary artery disease (50% or greater stenosis in at least one major coronary artery), a history of coronary bypass graft surgery or angioplasty, or hospitalization for an acute myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA) at least two months prior to eligibility screening, were administered the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire.22 Patients were excluded from participation if they: 1) had moderate to severe cognitive impairment, a major Axis I psychiatric disorder other than unipolar depression, psychotic features, a high risk of suicide, or current substance abuse other than tobacco use; 2) had an MI or acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the previous two months, a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30, advanced malignancy, severe valvular heart disease, or were physically unable to tolerate the study protocol; 3) were taking and planned to continue taking an antidepressant, an anticonvulsant, lithium, or over-the-counter omega-3 supplements; 4) had a known sensitivity to sertraline or omega-3; 5) were exempted by their cardiologist or primary care physician; or 6) refused to participate or to sign an informed consent form.

Patients who were not excluded by any of the above criteria and who scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 were scheduled for a structured clinical interview. Patients without exclusions who were found to meet the DSM-IV criteria for a current major depressive episode, as determined by the Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (DISH)23, and who scored 16 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)24 were enrolled in the trial. The self-described race and ethnicity of enrollees were recorded. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University Medical Center, Saint Louis, MO. Enrollment began in December 2005 and ended in December 2008.

Study Design

This study was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial comparing the efficacy of 50 mg/day of sertraline (Zoloft™) plus either two g/day of an omega-3 supplement (Lovaza™) or a corn oil placebo capsule. Fifty mg/day is considered a therapeutic dose of sertraline. There is only a marginal increase in the response rate but a significant increase in side effects at higher doses.25, 26 In order to avoid a possible imbalance in sertraline dosage between the groups, all patients were maintained on 50 mg/day throughout the 10 weeks of the trial.

The daily dosage of omega 3 acid ethyl esters, 930 mg of EPA and 750 mg of DHA, was selected based on Peat and Horribon’s 21 finding that doses higher than 1 g/day of EPA resulted in more side effects and a decrement in the augmentation effect. The choice of an omega-3 supplement that contained both EPA and DHA was based on Frasure-Smith et al.’s finding of low blood levels of DHA but not of EPA in depressed cardiac patients.5

The trial utilized sertraline (Zoloft) supplied by Pfizer, Inc., and an omega-3 capsule (Lovaza) and an identical corn oil (placebo) capsule provided by Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Inc. Lovaza is approved by the FDA for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia, but not for depression. Therefore, FDA approval (IND 71,095) was obtained for the use of Lovaza in this trial. The study complied with all FDA requirements.

Pre-Randomization Phase

After eligibility screening, participants were given a 2.5–3.5 week supply of sertraline 25 mg and a placebo capsule resembling the omega-3 capsules, with instructions for how to take them. After two weeks, they returned for a second diagnostic interview. The remaining pills and capsules were counted, and the patients were asked about medication side effects. The patients who continued to meet the DSM-IV criteria for major depression, scored ≥ 16 on the BDI-II, reported no serious side effects, took both drugs on at least 12 of the 14 days, and were not otherwise excluded, were invited to participate in the remainder of the study. Patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria for this phase of the study were referred back to their primary care physicians for further evaluation and possible treatment of depression.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)27 was administered to assess the self-reported severity of anxiety symptoms. In addition, 5cc of blood was drawn and the patient was fitted with an ambulatory ECG monitor for a 24 hour recording.

Randomization

A SAS program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to generate a random allocation sequence with block sizes of 3 and 6. The participants were randomly assigned to ten weeks of sertraline (Zoloft™) 50 mg plus two capsules per day of an omega-3 preparation (Lovaza™), or sertraline 50 mg plus a placebo (two grams of corn oil in identical capsules). The group assignments were concealed in sealed envelopes, and opened at enrollment by a clinical trial pharmacist who was blinded to all baseline assessments.

Treatment and Follow-up Phases

Only the study pharmacist and the chairperson of the data and safety monitoring committee were unblinded to group assignment during the trial; all other study personnel remained blinded throughout the trial. Depression symptoms were monitored weekly. The protocol required expeditious referral to a psychiatrist or primary care physician if a participant’s depression worsened significantly.

The participants were evaluated by the study psychiatrist (EHR) or a psychiatric nurse at baseline and at four and ten weeks after randomization. The sessions lasted approximately 30 minutes and included a review of the patient’s symptoms, adherence to the treatment protocol, and medication side effects. Telephone contacts were routinely made between visits to offer encouragement; check on progress; identify any new depressive symptoms, especially suicidal ideation; and answer study-related questions. Medication side effects, adverse events, and medical status were recorded at each visit and each weekly telephone contact. After 10 weeks of treatment, the participants again provided a blood sample, and completed the same assessments of depression and psychosocial functioning as were administered at baseline. Participants were compensated $100.00 for completing the baseline and the post-treatment assessments.

Treatment Adherence

At each visit, patients were given a sufficient supply of sertraline (one per day) and omega-3 or placebo capsules (two per day) to last an additional 5–8 days after their next scheduled visit. They were instructed to return all unused medications at each visit. The remaining tablets and capsules were counted and subtracted from the number of tablets originally provided to determine the number of pills taken during that period. An adherence index was defined as the number of pills removed from the bottle divided by the number prescribed for that period, multiplied by 100. The participants were asked to confirm that all pills removed were actually taken as prescribed. In addition, a measure of total red blood cell membrane EPA+DHA, developed by one of the investigators (WSH), was used to assess EPA/DHA blood levels at the baseline and post-treatment assessments. Blood FFA composition was assessed by capillary gas chromatography after extraction and conversion to FA methyl esters as described elsewhere.28

Data and Safety Monitoring

The principal investigator and co-investigators (KEF, EHR, MWR) were informed of all adverse events, significant worsening of depression, and suicidal features if and when they were identified by a study nurse or the study psychiatrist. An independent cardiologist, the study investigators, and the study nurses met quarterly to review both the serious and routine adverse events that had been reported during the previous three months, and to determine whether they were study-related. The study pharmacist and the independent cardiologist were informed immediately of all serious adverse events, and informed quarterly for routine adverse events by group. At each quarterly meeting, they advised the investigators as to whether to continue the study, based on the latest adverse event data.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests of association and analysis of variance models were used to compare the groups’ baseline demographic, psychiatric, and medical characteristics, and to identify post-treatment differences in protocol completion, adverse events, and side effects. Model diagnostics, including residual, influence, and outlier analyses, were performed for each statistical model.

Efficacy analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Some of the outcome data were plausibly missing at random (MAR). Consequently, multiple imputation was used to create 5 datasets based on an imputation model that included demographic, socioeconomic, cardiac, and depression history and severity characteristics. Analysis models were initially fitted to each imputed dataset. Each parameter estimate was then combined over the 5 imputed datasets.

Mixed-effects analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were utilized, consistent with the ITT principle.29 The primary model (ANCOVA I) was fitted to the weekly BDI-II data in order to test the hypothesis that depression is less severe after treatment among patients who receive sertraline plus omega-3 than among those who take sertraline plus placebo, while accounting for the correlations within subjects and measurement occasions. The model consisted of both fixed effects (treatment group, time, treatment group x time interaction, and the baseline BDI-II score) and random effects (subject). A fixed-effects ANCOVA model (ANCOVA II) was also used to test the primary hypothesis on the BDI-II and HAM-D, as well as to test for treatment effects on anxiety, using BAI data. These models were used to regress the post-treatment score on the group variable and on the pre-treatment score. The inclusion of the pre-treatment score increases the precision of the treatment efficacy test.

Additional secondary analyses were performed to compare the groups on remission (BDI-II ≤ 8) and improvement (≥50% reduction from the baseline BDI-II score) at 10 weeks post-randomization. Odds ratios were obtained from logistic regression models to determine the strength of the association between group assignment and the probability of remission or improvement. Planned comparisons were conducted to test for gender and minority moderation of the primary outcome, by adding main effects for gender and minority status and their interactions with treatment group to the primary statistical model. To compare the course of depression between the groups, a profile plot was constructed from the ANCOVA I model estimates. Completer analyses were also conducted. All hypothesis tests were two-tailed with p<0.05 denoting statistical significance. No major violations of model assumptions and no influential observations were identified for any of the statistical models. SAS© version 9.1 was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

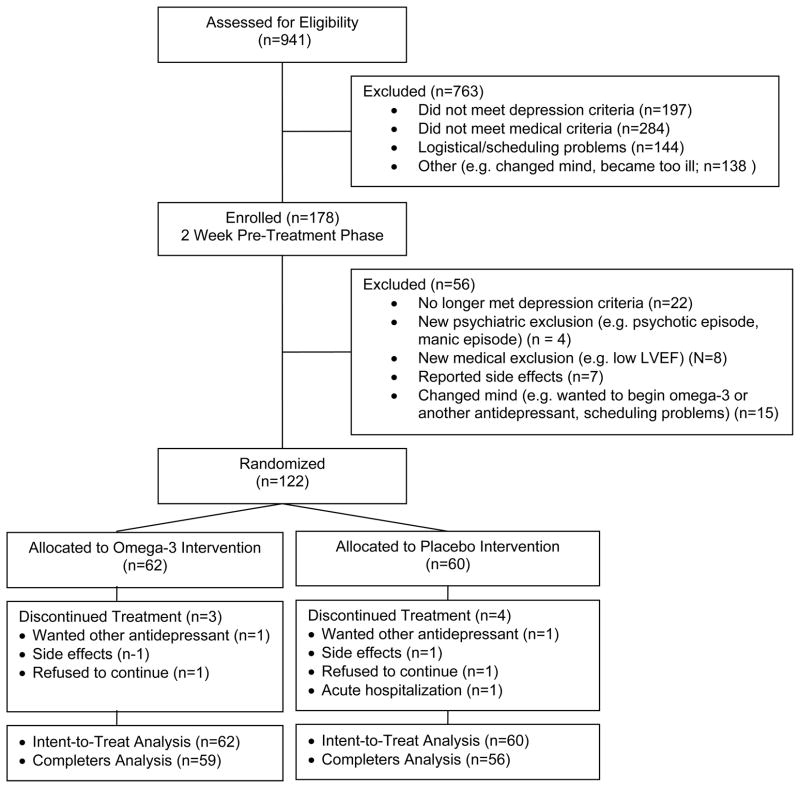

Nine hundred forty-one patients expressed interest in the study (Figure 1). A total of 178 patients met all of the study’s eligibility criteria, including the DSM-IV criteria for major depression, and were enrolled in the pre-randomization phase of the study. After two weeks on sertraline 25 mg/day plus two placebo capsules per day, 122 patients continued to meet all of the eligibility criteria and agreed to remain in the study. Sixty patients were randomly assigned to the placebo arm and 62 to the omega-3 arm. Four subjects in the placebo arm and three in the omega-3 arm dropped out of treatment before completing the 10-week treatment protocol and post-treatment assessment. Two withdrew in order to try a different antidepressant, two withdrew due to symptoms possibly related to sertaline (insomnia, dizziness), two refused to return for scheduled visits without explanation, and one experienced worsening of a preexisting medical condition that required a lengthy hospital stay. Fifty-nine (95%) of the patients assigned to the omega-3 arm and 56 (93%) of those assigned to the placebo arm completed all phases of the study, including the post-treatment assessment.

Figure 1.

Trial Flow Chart

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline medical, demographic, and depression history data are presented by group in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups except for a higher proportion (88.3%) of aspirin use in the placebo arm than in the omega-3 arm (72.6%; p = .03). The patients in the placebo group tended to have higher total cholesterol and fasting triglycerides, and were somewhat more likely to have diabetes, than those in the omega-3 arm. Baseline omega-3 index levels were in the normal range.30 Most of the participants entered the study with histories of depression and depression treatment. The mean duration of the current depressive episode was slightly longer than 14 months in each group.

Table 1.

Omega-3 Study Baseline Demographic and Medical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Group Assignment

|

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=60) | Omega3 (n=62) | ||

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 58.6 ± 8.5 | 58.1 ± 9.4 | .79 |

|

| |||

| Gender (Female) | 31.7% | 35.5% | .66 |

|

| |||

| Caucasian | 81.7% | 79.0% | .71 |

|

| |||

| Education > 12 years | 61.7% | 64.5% | .74 |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.6 ± 7.3 | 33.8 ± 7.3 | .39 |

|

| |||

| Cigarette Smoker | |||

| Ever | 75.0% | 77.4% | .75 |

| Current | 21.7% | 27.4% | .46 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 80.0% | 74.2% | .45 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 43.3% | 29.0% | .10 |

|

| |||

| History of MI/ACS | 55.0% | 64.5% | .28 |

|

| |||

| History of CABG | 36.7% | 32.3% | .61 |

|

| |||

| History of PTCA | 66.7% | 62.9% | .66 |

|

| |||

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society Angina class | .12 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 78.0% | 60.7% | |

| I | 0% | 3.3% | |

| II | 5.1% | 4.9% | |

| III | 1.7% | 9.8% | |

| IV | 15.3% | 21.3% | |

|

| |||

| Fish Consumption (average number of servings per week) | .60 ± .65 | .52 ± .73 | .50 |

|

| |||

| Baseline medications | |||

| Aspirin | 88.3% | 72.6% | .03 |

| Ace inhibitors | 46.7% | 51.6% | .58 |

| Beta blockers | 83.3% | 79.0% | .54 |

| Statins | 75.0% | 72.6% | .76 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 23.3% | 32.3% | .27 |

|

| |||

| Lipids | |||

| Omega-3 Index (DHA + EPA; % in RBC) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | .95 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 175.3 ± 39.8 | 161.1 ± 45.1 | .07 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 43.2 ± 13.0 | 43.3 ± 13.8 | .99 |

| Triglycerides, fasting (mg/dL) | 198.3 ± 135.2 | 161.6 ± 93.3 | .09 |

|

| |||

| Depression | |||

| History of depression | 74.1% | 63.3% | .21 |

| Duration of current depressive episode (months) | 14.1 ± 18.8 | 14.2 ± 15.5 | .98 |

| History of depression treatment | 65.0% | 59.7% | .54 |

Continuous variables are reported as means ± standard deviations; categorical variables are listed as percentage of subjects with the characteristic. Chi-square tests and analyses of variance were used to determine significance.

The mean baseline BDI-2 and HAM-D scores (29.0 and 19.2 [placebo], 28.1 and 21.2 [omega-3], respectively) are consistent with moderate to severe depression (Table 2). The mean HAM-D score at baseline was significantly higher in the omega-3 group (21.2 ± 5.6) than in the placebo group (19.2 ± 5.1, p = .04).

Table 2.

Primary/Secondary and Adherence Outcome Comparisons at Baseline (B) and 10-Week Post FU (P)

| Measure | Group Assignment

|

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=60) | Omega3 (n=62) | ||

|

| |||

| Primary | |||

| BDI-II | |||

| Pre | 29.0 ± 9.2 | 28.1 ± 8.7 | .59 |

| Post | 15.0 ± 9.7 | 15.9 ± 10.2 | .64 |

| HAM-D-17 | |||

| Pre | 19.2 ± 5.1 | 21.2 ± 5.6 | .04 |

| Post | 9.1 ± 6.7 | 9.7 ± 6.5 | .61 |

| Secondary | |||

| BAI | |||

| Pre | 15.2 ± 9.9 | 16.1 ± 8.8 | .59 |

| Post | 11.0 ± 10.1 | 10.9 ± 9.2 | .96 |

| Mean treatment adherence (% days pill removed) | |||

| Omega-3/Placebo | 97.3 ± 3.1 | 97.4 ± 4.3 | .97 |

| Sertraline | 98.5 ± 2.6 | 98.6 ± 3.1 | .88 |

| Omega-Index (% EPA + DHA in RBC) | |||

| Pre (n=121) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | .95 |

| Post (n=114) | 4.6 ± 1.2 (n=55) | 7.6 ± 1.8 (n=59) | <.0001 |

Continuous outcomes are reported as mean ± SD.

Keywords: BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II; HAM-D-17 = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; EPA = eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA = docosahexaenoic acid; RBC = red blood cells

Adherence to Treatment Regimen

Adherence to the medication regimen was ≥97% in both groups for both medications (Table 2). Omega-3 levels blood levels (percent DHA+EPA in red blood cells) were measured at the post-treatment evaluation (n=114; seven participants failed to complete the study, and another refused to provide blood samples due to a severe needle phobia). The levels were nearly identical between the groups at baseline. The placebo group was unchanged from baseline, whereas the omega-3 group increased from 4.6% to 7.6% (p<0.001) as expected (Table 3).28

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Depression and Anxiety Outcomes

| Outcome | Statistical Model1 | Parameter2 | ITT Estimate (95% CI)3 | Test Statistic4 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Beck Depression Inventory II | ANCOVA I | Between-Group Difference in Post-Means | −1.39 (−4.48, 1.71) | t116 = −.89 | .38 |

| ANCOVA II | Between-Group Difference in Post-Means | −1.26 (−4.48, 1.97) | t116 = −.77 | .44 | |

|

| |||||

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | ANCOVA II | Between-Group Difference in Post-Means | .14 (−2.15, 2.44) | t115 = .12 | .90 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | Between-Group Difference in Post-Means | .59 (−2.31, 3.49) | t113 = .40 | .69 | |

|

| |||||

| Remission (BDI-II ≤ 8) | LOGISTIC | Intercept | .40 (.22, .71) | t106 = −3.16 | .002 |

| Treatment Group | .96 (.43, 2.15) | t113 = −.11 | .91 | ||

| Improvement (>50% reduction in BDI-II from baseline) | Intercept | .91 (.54, 1.55) | t101 = −.35 | .73 | |

| Treatment Group | 1.06 (.51, 2.19) | t112 = .15 | .88 | ||

An explanation of the statistical models is provided in the statistical analysis section.

Between-group differences (BGD) reflect placebo minus omega-3 group means. Estimates from both ANCOVA models are adjusted for the baseline score. For the remission and improvement outcomes, the placebo arm is the reference group.

Estimated odds ratios are used to describe remission and improvement outcomes.

Empirical degrees of freedom (EDFs) were computed from the multiple imputation inferential procedure.

Post–Treatment (10-week) Outcomes

Study participants were assessed again after 10 weeks and data were collected for both primary (BDI-II, HAM-D-17) and secondary (BAI) measures (Table 2). Both arms showed significant improvement from the baseline assessment on all measures, but there were no significant differences between the groups.

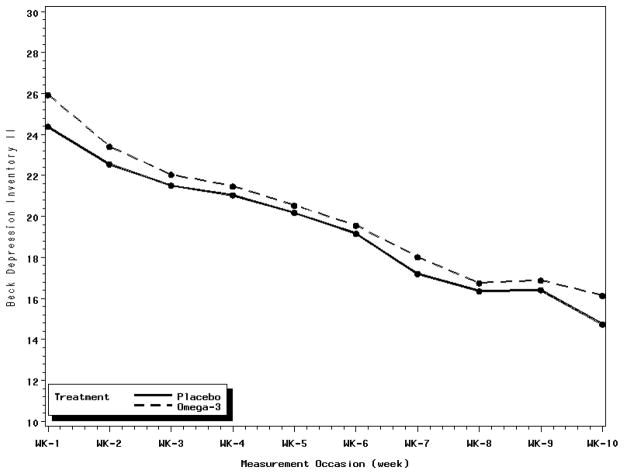

As shown in Table 3, neither the weekly BDI-II scores nor the pre-post BDI-II change scores differed between the omega-3 (mean pre-post change = 12.2) and placebo (mean pre-post change = 14.0) groups. A profile plot (Figure 2) based on the ANCOVA I model estimates displays the weekly course of depression by treatment group. Depressive symptoms improved over time in both groups at essentially the same rate. Neither the HAM-D nor the BAI differed between the groups (Table 3). Neither remission (28.3% omega-3 vs. 27.4% placebo) nor treatment response (47.7% omega-3 vs. 49% placebo) differed significantly between the groups (Table 3). There was no evidence of moderation by gender or minority status for any of the primary or secondary outcomes.

Figure 2.

Profile plot of the weekly course of depression by treatment group. Weekly depression estimates are adjusted for the baseline depression score.

All of the analyses reported above were repeated for the subgroup of study completers (n=115). These results (not shown) differed only marginally from those of the ITT analyses.

Side Effects and Symptoms

Overall, 22% of the placebo arm participants and 19% of those in the omega-3 arm reported symptoms that have been associated in previous studies with high doses of omega-3, including gastrointestinal complaints, diarrhea, bloating, or prolonged bleeding (p=0.72). There were no differences between the groups in the frequency of any of these symptoms. Prolonged bleeding was reported by one patient who was assigned to the placebo group. There was only one between-group difference ≥ 5% for any reported symptom: Stomach upset was reported by 10% of the placebo and 3% of omega-3 participants. Thus, most patients in the omega-3 group tolerated 2 grams per day of omega-3 very well.

There were no differences between the groups in the frequency of symptoms associated with other systems, including neurological and cardiovascular, nor in side effects commonly reported by patients taking sertraline. Overall, 73% of the placebo group and 63% of the omega-3 group reported at least one new symptom during the 10 weeks of study (p=0.24).

Safety

Fourteen adverse events resulted in either a visit to an emergency department or hospitalization. Both groups had four cardiac and four non-cardiac hospitalizations. One patient in the placebo arm experienced an acute MI, two omega-3 patients and one placebo patient underwent coronary angioplasty, one omega-3 patient was hospitalized for syncope, one placebo patient for implantation of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD), and one placebo patient had cardiac ablation for atrial flutter. Both groups also had four non-cardiac hospitalizations, all for conditions that were not life threatening such as influenza, edema, or removal of benign cyst. Both groups had three emergency department visits that did not lead to hospitalization. The reasons for these visits among the omega-3 patients were worsening heart failure, injury from a fall, and kidney stones. The visits for the placebo patients were for severe influenza, a possible allergic reaction to a nonstudy medication, and a minor accident. After careful review, none of these events were classified as study-related by the data and safety monitoring committee.

DISCUSSION

The results of the trial did not support the hypothesis that co-administration of 2 g/day of omega-3 FA improves the efficacy of 50 mg/day of sertraline in patients with major depression and heart disease. These results are inconsistent with previous studies of depressed psychiatric patients that found omega-3 supplements to substantially improve the efficacy of standard antidepressants. However, there are other studies of depressed psychiatric patients that have also failed to find a beneficial effect for omega-3 taken alone or in combination with antidepressants.31 Lin and Su completed a meta-analysis of ten studies of omega-3 treatment for patients with either unipolar or bipolar depression.19 They found a significant antidepressant effect for omega-3, but noted that there was considerable heterogeneity among the studies. No reliable moderators of the antidepressant effect of omega-3 have emerged from this literature.

The participants in this study received 50 mg per day of sertraline for the ten-week duration of the trial. It is possible that omega-3 augmentation would have been more effective at higher doses of the antidepressant. However, previous studies found little additional improvement in response rates with higher doses of sertraline (100–200 mg per day), whereas they did find a significant increase in side effects.25, 26 Furthermore, increasing the dose of sertraline for participants who did not respond to 50 mg could have resulted in an imbalance in dosage between the groups. This would have likely occurred if the hypothesized omega-3 effect had been observed. Nevertheless, whether omega-3 is more effective in combination with higher doses of sertraline is unknown.

The choice of the omega 3 dosage was based on a study by Peet and Horribon21 who found that higher doses of EPA omega-3 (> 1 gram/day) resulted in more reported side effects without any additional improvement in depression. Nevertheless, it is possible that higher doses of omega-3 would have had a beneficial effect in the present study. Two capsules of Lovaza contain just below one gram of EPA (930 mg). Both the pill counts and RBC levels of EPA and DHA indicated a very high adherence rate, suggesting that nearly all patients took at least this amount daily. In order to ingest one gram or more of EPA per day, three or more pills of any formulation available at the time the study began would have been required. Increasing the number of pills per day or the total amount of EPA received could have decreased adherence to the treatment regimen and worsened the depression outcomes by increasing both the complexity of the medication regimen and drug-related side effects. The meta-analysis by Lin and Su found larger effect sizes for studies that used higher doses of EPA, but the differences were not statistically significant and not every study using a higher dose of EPA found it to be effective.e.g.32 Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether higher doses of omega-3 can improve depression in patients with CHD.

It is also possible that DHA may be more important than EPA for treating depression in patients with CHD. An earlier study5, later confirmed4, 6, found that blood levels of DHA but not EPA were lower in depressed cardiac patients. Although patients in the present trial received a daily dose of 750 mg of DHA, that may not be enough to produce an effect on depression in cardiac patients.

The trial was limited to 10 weeks, which may not have been long enough to observe an effect for omega-3. However, there is no indication that a longer treatment period would have resulted in an outcome favoring the omega-3 group. Although both groups showed improvement, the between-group difference in weekly BDI-II scores remained nearly identical throughout the trial (Figure 2). Furthermore, earlier positive studies found effects within ten weeks.e.g.20

We proposed to enroll 175 patients and expected to randomize 150 after the two week run-in phase during which patients received 25 mg of sertraline and placebo capsules. We actually enrolled 178 patients with a major depression episode who met all of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, 58 instead of the expected 28 patients were excluded or dropped out before randomization. In most cases, this was due to improvement in depression which placed the patient below the eligibility threshold (n=22); a decision by the patient to avoid possible randomization to a placebo and to seek omega-3 and antidepressants elsewhere (n=15); or new or previously unidentified medical or psychiatric exclusions (n=12). Although the enrolled sample was smaller than planned, it is unlikely that a different outcome would have been observed if the proposed 150 or even 200 patients had been randomized. The mean BDI-II between-group difference was negligible.

Although some trials of omega-3 for depression have been strongly positive, others, including the present study, have failed to demonstrate a benefit of omega-3, either alone or combined with conventional antidepressants. These contradictory findings mirror those of studies that have examined the efficacy of omega-3 supplements in reducing cardiac morbidity and mortality.33, 34 Some studies have found that omega-3 supplements greatly reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death.15–17 Others have failed to find a benefit, and still others have reported that omega-3 supplements increase the risk of cardiac death.35 These confusing results have led to speculation about the clinical characteristics of cardiac patient subsets who may either benefit or be harmed by increased intake of omega-3.34, 36, 37 Similar attempts should be made to identify the characteristics of the depressed patients who benefit from omega-3 depression monotherapy or augmentation of standard antidepressants. Confirmatory prospective clinical trials should then be undertaken in these subgroups. To this end, secondary and exploratory analyses are currently being conducted to determine whether any subgroups benefited from omega-3 in this study.

In conclusion, this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found no evidence that omega-3 augmentation of sertraline is superior to sertraline plus placebo capsules for depression in patients with major depression and established CHD. Whether higher doses of EPA and/or DHA, higher doses of sertraline, a longer duration of treatment, or the use of omega-3 as a monotherapy, can improve depression in patients with stable heart disease remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by Grant No. RO1 HL076808-01A1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The investigators express their gratitude to Dr. Ronald Krone for his service on the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee and to Stephanie Porto RPh, Julie Nobbe, PharmD, Patricia Herzing RN, Cathi Klinger RN, and Carol Sparks, LPN, Tiffany Bonds, and Kim Metze for their contributions to the conduct of the trial. The investigators would also like to thank Drs. Nancy Frasure-Smith and Francois Lespérance for providing valuable advice in the planning of the study. Finally, the investigators thank Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Inc for supplying Lovaza (omega-3) and placebo capsules, and Pfizer, Inc., for supplying Zoloft.

References

- 1.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:802–13. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 2008;121:S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Melle JP, de JP, Spijkerman TA, et al. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:814–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin AA, Menon RA, Reid KJ, Harris WS, Spertus JA. Acute coronary syndrome patients with depression have low blood cell membrane omega-3 fatty acid levels. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:856–62. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318188a01e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Julien P. Major depression is associated with lower omega-3 fatty acid levels in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:891–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker GB, Heruc GA, Hilton TM, et al. Low levels of docosahexaenoic acid identified in acute coronary syndrome patients with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbeln JR. Fish consumption and major depression. Lancet. 1998;351:1213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Belury MA, Porter K, Beversdorf DQ, Lemeshow S, Glaser R. Depressive symptoms, omega-6:omega-3 fatty acids, and inflammation in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:217–24. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180313a45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severus WE, Littman AB, Stoll AL. Omega-3 fatty acids, homocysteine, and the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in major depressive disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:280–93. doi: 10.1080/10673220127910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sontrop J, Campbell MK. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and depression: a review of the evidence and a methodological critique. Prev Med. 2006;42:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–57. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Psota TL, Gebauer SK, Kris-Etherton P. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:3i–18i. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haag M. Essential fatty acids and the brain. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:195–203. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horrobin DF, Bennett CN. Depression and bipolar disorder: relationships to impaired fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism and to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, immunological abnormalities, cancer, ageing and osteoporosis. Possible candidate genes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1999;60:217–34. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albert CM, Campos H, Stampfer MJ, et al. Blood levels of long-chain n-3 fatty acids and the risk of sudden death. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1113–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2:757–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leon H, Shibata MC, Sivakumaran S, Dorgan M, Chatterley T, Tsuyuki RT. Effect of fish oil on arrhythmias and mortality: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2931.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin PY, Su KP. A meta-analytic review of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1056–61. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemets B, Stahl Z, Belmaker RH. Addition of omega-3 fatty acid to maintenance medication treatment for recurrent unipolar depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:477–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peet M, Horrobin DF. A dose-ranging study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with ongoing depression despite apparently adequate treatment with standard drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:913–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, et al. The Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (DISH): rationale, development, characteristics, and clinical validity. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:897–905. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000028826.64279.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67:588–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabre LF, Abuzzahab FS, Amin M, et al. Sertraline safety and efficacy in major depression: a double-blind fixed-dose comparison with placebo. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:592–602. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweizer E, Rynn M, Mandos LA, Demartinis N, Garcia-Espana F, Rickels K. The antidepressant effect of sertraline is not enhanced by dose titration: results from an outpatient clinical trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:137–43. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris WS, von Schacky C. The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Prev Med. 2004;39:212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallinckrodt CH, Sanger TM, Dube S, et al. Assessing and interpreting treatment effects in longitudinal clinical trials with missing data. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:754–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Block RC, Harris WS, Reid KJ, Sands SA, Spertus JA. EPA and DHA in blood cell membranes from acute coronary syndrome patients and controls. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:821–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appleton KM, Hayward RC, Gunnell D, et al. Effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood: systematic review of published trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1308–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silvers KM, Woolley CC, Hamilton FC, Watts PM, Watson RA. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of fish oil in the treatment of depression. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;72:211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooper L, Thompson RL, Harrison RA, et al. Risks and benefits of omega 3 fats for mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:752–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38755.366331.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.London B, Albert C, Anderson ME, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiac arrhythmias: prior studies and recommendations for future research: a report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office Of Dietary Supplements Omega-3 Fatty Acids and their Role in Cardiac Arrhythmogenesis Workshop. Circulation. 2007;116:e320–e335. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burr ML, Ashfield-Watt PA, Dunstan FD, et al. Lack of benefit of dietary advice to men with angina: results of a controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:193–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert CM. Omega-3 fatty acids and ventricular arrhythmias: nothing is simple. Am Heart J. 2008;155:967–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Den Ruijter HM, Berecki G, Opthof T, Verkerk AO, Zock PL, Coronel R. Pro- and antiarrhythmic properties of a diet rich in fish oil. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]