Abstract

Background

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) has been designed for use by trained laypersons. It therefore shows great promise for use in developing countries such as South Africa, where there is a lack of clinically trained and skilled professionals at the primary care level. Against this background, the aim of the current study was to investigate the sociocultural appropriateness of the DISC-IV for use with Sesotho families in South Africa.

Methods

Qualitative methodology of expert review and contextualized content analyses were used. Ten Sesotho-speaking clinicians were recruited through a snowball sampling technique to the review the DISC through expert review reports.

Results

Several themes emerged, including the structure of the DISC-IV, its computerized nature, Americanisms, problems in interpretation due to the adversity children live under, language problems, the effect of rural settings and education level, and cultural norms regarding psychiatric symptoms, gender, the experience of time, the expression of emotion, and family structure.

Conclusion

Recommendations for the sociocultural adaptation and translation of the DISC into Sesotho are made.

Keywords: DISC-IV, Cultural appropriateness, South Africa, Diagnostic interview schedule for children, Children

Introduction

The NIH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) [1] is one of the most widely used diagnostic instruments for children and adolescents. It covers the DSM-IV, DSM-III-R, and lCD-10, for over 30 diagnoses. Originally designed as a research tool, the popularity of the DISC in both research and clinical settings may be attributed to its comprehensive nature and the fact that it has very good psychometric properties. It is highly structured, with mostly closed questions and requires interviewers to adhere to its structure without deviations. This, and the fact that it is strictly respondent-based (not dependent upon clinical judgment) allows for its use by trained lay interviewers. It furthermore generates instant reports through computer-assisted administration, and can be self-administered. Taken together, the DISC is ideal for large-scale research studies because it is low in cost and easy to administer. Versions of the DISC have been used in Australia, Canada, China, England, Iceland, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Scotland, and Venezuela [2].

Beyond its established use in developed countries, the DISC shows potential for use especially in developing countries where there is a lack of clinically trained and skilled professionals at the primary care level. South Africa is such a developing country where there is an estimated rate of 4 psychologists per 100,000 population as compared with 26.4 psychologists per 100,000 in the USA [3]. Moreover, a recent study estimated an average of 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 in South Africa [4]. In a review of referrals from a community outreach service in South Africa [5], it was concluded that in the context of the paucity of specialist psychological and psychiatric services there is an urgent need for the development of psychometric assessment tools in South Africa. This necessity is further compounded by the worldwide shift towards a more community-based psychiatric service delivery approach [6], and newly articulated norms for mental health services in South Africa [4].

Such development would necessarily include a focus on the cultural relevance of the diagnostic tool in question. Although most major diagnostic categories have been shown to have cross-cultural validity [7], diagnostic tools and treatment will vary across countries, regions, cities, and even neighborhoods [8]. It has been known for some time that culture-free psychometric tools do not exist and that a more realistic aim is the adaptation of tools that are “culture-reduced” or “culture-common” [9]. Test adaptation refers to the process of making a measure more applicable to a specific cultural context while using the same language [10]. Thus, words, context, and examples are changed to be more relevant and applicable to a specific language, national and/or cultural group and therefore necessitates incorporating local views into measure development [11].

Despite the advantages the DISC holds for research and clinical use in South Africa, it has not yet been evaluated for its sociocultural appropriateness. Thus, its potential to be adapted in a culture-reduced or culture-common fashion is not known. The parent-report version of the DISC was translated into Xhosa and used in a township outside Cape Town [12, 13]. While these studies demonstrated the practical feasibility of the DISC, it did not address its cultural appropriateness. Moreover, South Africa has 11 official languages with associated cultural differences. For instance, Sotho and Xhosa are two relatively unrelated languages that are not mutually intelligible and that can be regarded as representing different linguistic frameworks of reference. Although both are so-called “Bantu” languages, Sotho belongs to the Niger-Congo family of languages, while Xhosa is part of the Nguni languages of Southeast Africa, whose relationship to the Niger-Congo group of Bantu languages is difficult to trace. Therefore, any psychiatric tool needs to be evaluated for its cultural appropriateness for each of the language/culture groups.

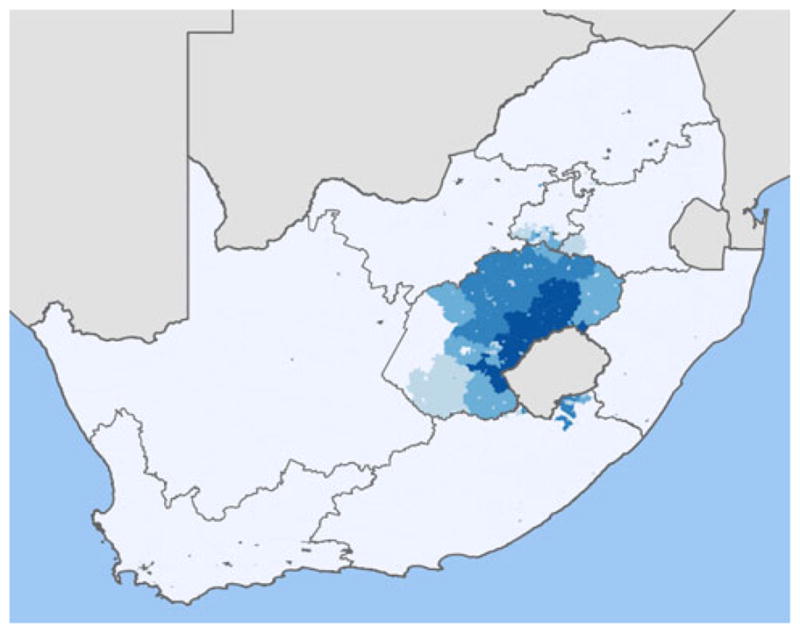

Against this background, the aim of the current study was to investigate the sociocultural appropriateness of the DISC to identify children with emotional-behavior disorders in the context of the Sesotho culture in South Africa. According to the 2001 South Africa Census, Sesotho is spoken by approximately four million people (8% of the population) and it is the language spoken mostly in the Free State Province, of which the city of Bloemfontein is the capital (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of distribution of Sesotho speakers in South Africa: darker shading indicates denser population of Sesotho speakers in the Free State Province (Statistics South Africa, 2007)

By developing diagnostic tools relevant to the local Sesotho culture we, like others in other developing countries and regions [11], hope to stimulate the assessment of mental health needs and associated risk and protective factors.

Methods

Methodological framework

Given that this is the first study to investigate the sociocultural appropriateness of the DISC, the methodology of expert review—see [14] for a discussion—combined with contextualized content analysis [15] was chosen. An expert review requires that a group of experts be convened to evaluate the features of a measure or tool. This may include question wording, instructions, structure, flow, and layout. Expert review offers a systematic and formal method of evaluation that does not require any fieldwork. It is ideally conducted in advance of fieldwork as it can reveal potential problems and associated solutions as well as recommendations for further stages of testing and development.

Participants and recruitment strategy

After ethics approval was obtained from all participating institutions, 10 Sesotho-speaking clinicians working in Bloemfontein, South Africa, were recruited to form an expert review panel. According to the Health Professions Council of South Africa there are currently 15 registered Black clinical psychologists in the Free State Province (compared to 50 White clinical psychologists). It is not clear how many of these are Sesotho speaking. As reported above, there are an average of 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 in South Africa, with 0.1 psychiatrists per 100,000 in the Free State Province [4], which has a population of 2,773,059 [16]. It is unclear how many of these are Black Sesotho-speaking psychiatrists. Given the alarmingly low numbers of trained Sesotho-speaking mental health professionals in the Free State Province, the method used for identifying the participants was that of snowball sampling [17]. This method is often used in studies of cultural validation and adaptation of research instruments under conditions of scarce resources, including the limited availability of mental health professionals [18]. First, the Department of Psychology of the University of the Free State was asked to identify former clinical psychology trainees and psychologists through departmental internship partners and the government psychiatric hospitals. Others were identified through the public psychiatric service and private clinical practice. Once a clinician was identified he/she was requested to suggest any possible colleague known to them according to the snowballing approach. The key concern was to identify as many as possible of the few Sesotho-speaking mental health professionals working in Bloemfontein; the sampling was stopped only when it was clear that the pool of eligible clinicians was exhausted.

Of the 10 clinicians, three were male. Five were licensed clinical psychologists (thereby constituting 33% of all licensed Black clinical psychologists in the Free State Province) and one was a student completing her clinical psychology internship. Four participants were licensed social workers working in mental health settings. On average, clinicians had 5 years of experience working in mental health.

Procedures

Clinician reviewers underwent a 1-day training course in the DISC by the first author (CS) who received training on the DISC at Columbia University from one of the original developers of the DISC. Training of clinicians included teaching on the philosophical underpinnings of the DISC, its development, its installation, and its administration. Each of the relevant modules was discussed and a demonstration of the use of the DISC was given.

Each of the reviewers received their own computerized copy of the DISC as well as the DISC manual and a document outlining the terms of reference for the expert review—see [19] for a description of a “clear terms of reference approach” to report generation. Their task was to review the DISC for use among Sesotho parents and their children in the Free State, especially looking at its sociocultural appropriateness. Modules of the DISC that pertain to emotional-behavior disorders in children were selected. The Anxiety Disorders module included generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and separation anxiety disorder (SAD). The Mood Disorders module included major depressive disorder (MDD). The Disruptive Behavior Disorders module included attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD). Reviewers were asked to produce a five-page report detailing the findings of their review. In assessing its appropriateness we followed the following guidelines from the APA Handbook of Psychiatric Measures [20] such as: (1) appropriate categorization of phenomena as either pathological or non-pathological depending upon the social/cultural context; (2) the content or clustering of pathological symptoms among Sotho-speaking children and adolescents; (3) the use of the specific words/ways to describe distress and symptoms of emotional-behavior disorders, namely, “idioms of distress”; and (4) the likely understanding of the constructs by lay Sesotho speakers. Clinicians were given 10 weeks to review the DISC and compile their reports. They were paid a per-hour rate equivalent to clinical practice income. Original, de-identified reports are available for scrutiny from the first author (CS).

Data analyses

Once the reviews were received they were combined into a single report using a modified contextualised content analysis approach [15]. The reports were analyzed using the broad thematic areas outlined in the terms of reference provided to the reviewers. Additional thematic areas were added based on the content of the reports, such as the impact of administering the DISC by computer on rapport-building. To ensure reliability, the two-first authors first analyzed the reports separately. Discrepancies in the comparison of the independent analyses were reviewed against the original reports to ensure accuracy and validity. These two analyses were then combined, and the final report was agreed upon by both authors. The Results section below contains the combined review of which much of the material is drawn directly from the reviewers. Contributions are generally not attributed to a particular reviewer. Given the similarity between the experts in terms of background and qualification, quotes are not attributed to any specific source.

Results

Overall comments on the DISC

Reviewers expressed appreciation for acknowledging the importance of investigating the cultural appropriateness of the DISC as this has been a significant limitation in many of the psychological instruments used in the South African context. Overall, reviewers concurred that the DISC has significant potential for use as a diagnostic tool in the Sesotho context as it could contribute significantly to the comprehensive understanding of the client as it tends to tap a lot of information in a very short period of time. Moreover, it was acknowledged that the DISC could be used in clinical settings as an initial screen, which would provide psychiatric information beyond the referral information and the mental exam. Furthermore, it was acknowledged that the DISC was well researched and based on the diagnostic system of the DSM-IV used worldwide.

However, significant limitations relating to culture and context were also acknowledged resulting in a strong recommendation that the DISC be translated into Sesotho. Such translation would not only address the language issues raised, but also the sociocultural themes that emerged.

The structure and organization of the DISC

A key theme was that the DISC was easy to administer because questions are clear, well structured and organized into relevant modules. The fact that the DISC is organized into modules was deemed positive in that clinicians could exercise choice as to which disorders to focus on. A further helpful feature was noted by one respondent as the comparable child and parent versions of the DISC. Questions were deemed developmentally sensitive.

While the DISC is considered a brief instrument given its comprehensive nature, there was a concern that the sheer number of questions may lead to boredom and monotony for respondents, as well as lengthy administration time. In addition, concerns were expressed about the level of repetition in the DISC, owing to the lifetime, past year, and past 4 weeks prevalence questions. The full DISC with all this repetition was felt to be too long to administer and beyond the tolerance limits of most parents or children.

All respondents commented on the limitations of the closed questioning and binary response options (yes/no) to all DISC questions. Although this reduces irrelevant and unnecessary responses to the questions, it does not allow for elaboration. Neither does it allow for the subjective experience of symptoms to be described or the more narrative style of description typical among Sotho language speakers. For instance, a Sesotho-speaking child can experience stomach pains or headaches without any medical reason, but the DISC does not give them the option to elaborate about what the cause of these may be when asking about physical symptoms. One solution to the all or nothing approach of a yes/no response set, was that at least four or five different alternatives such as “yes, no, sometimes, most of the times, always and never” should be provided. A related subtheme was that the structured nature of the test eliminated the spontaneity that is normally expected within the assessment session/setting.

The computerized nature of the DISC

Criticism of the computerized nature of the DISC centered around its affect on rapport-building. There was a strong shared concern that eye contact may be affected, which clinicians felt was important to communication and the development of a therapeutic relationship. Movements from shifting the computer-mouse as the interviewer navigates from one question to the next may distract the interviewee, again affecting rapport. The computer may also cause anxiety given the lack of experience with computers for most Sesotho-speaking families. In addition, while entering answers into the computer, important behavioral observations may be missed. This would improve as the interviewers became more familiar with the technology.

In contrast to the disadvantages outlined above, some advantages associated with the computerized nature of the DISC were acknowledged. The computer-based method was seen as user-friendly, allowing for termination of the interview according to the needs of the interviewer and the respondent. It was felt that this flexibility may, in turn, improve concentration and cultivate interest during the interview. The ability to take computerized notes during the interview was deemed helpful; all adding to the conclusion that this method was electronic, fast, easy to use, avoiding of human error, and convenient for both the interviewer and the interviewee. The possibility of an immediate report that could be printed out was seen as very appealing. A strength pointed out was the fact that continuity between items is maintained by the computerized program registering answers to previous questions and building those into follow-up questions in each module.

Americanisms

A strong theme that emerged is the number of American-specific constructs in the DISC that will have to be adapted for the South African context: The American grade system (e.g. “kindergarten” should be “pre-school”); American seasons (e.g. “fall” should be “autumn”); time line of the education system (school starts in January in South Africa), “terms” rather than “semesters”, and “homework” rather than “assignment”. In addition, in the PTSD module terms such as ‘tornado’ or ‘hurricane’ were not appropriate for use with village or squatter camp children; instead terms like floods, “veld (bush) fires”, “shack fires” or car accidents were recommended. Any reference to “dollar” should be replaced by the South African currency “rand”.

Problems in interpretation due to adversity

A core theme was that the DISC is currently insensitive to the adverse circumstances that Sesotho children grow up in. This centered on two particular issues, namely poverty at an individual and community level; and the loss of parents due to AIDS, violence, desertion or other causes. Some examples or specific items included the following.

The targets of the timeline used to help parents remember important events (e.g. vacations) were deemed irrelevant to many children’s lives, e.g. few children have the opportunity to take vacation. References to an apartment or house were deemed inappropriate for a child from the squatter camps or villages of South Africa, where the terms “shack” or “hut” are more appropriate. In the ADHD module phrases like “on a chair in a restaurant” were thought to be inappropriate as many children might have not been in restaurant before. So were references to ‘credit card’, given that most children and communities were disadvantaged.

Given the high rate of parental death, guardians interviewed may have lived with the child for less than 6 months and may be the third or fourth set of guardians for the child, and will neither know the child well, nor be able to make use of the timeline that is provided to diagnose problems. A similar problem may arise around age of onset question. It was suggested that a question regarding the length of time that the guardian has lived with the child be built into the Demographic module. The use of the extended family to provide care for the child may build in some connective memory, but as the number of children in need of care rises, so does the capacity of this memory and of the extended family to provide care.

In the Conduct Disorder (CD) module the question regarding skipping school requires qualification as some children who skip school are forced by circumstances to do so (e.g. taking care of ill parents or not having money to attend). Also, in the CD module it was recommended that the question regarding damage to property be rephrased as most children do not have adequate playgrounds and thus often play in the street next to houses where the chances of them breaking or damaging windows is higher.

Cultural norms and psychiatric symptoms from a Sesotho perspective

Clinicians reviewing the DISC identified one of its outstanding features as its adherence to the DSM-IV diagnostic system, thus aiding in diagnostic efficiency. The DISC was praised for not only determining if exhibited behavior is the patient’s usual behavior or not, but also in determining severity of deterioration. The inclusion of somatic complaints was also praised as most Black people tend to express their emotions through somatic complaints. In addition, there was general agreement that questions were asked in a way that would not be seen as offensive in the Sesotho culture. Most importantly, the modules selected for the expert review covered disorders and symptoms that were exhibited amongst Sesotho children. As one reviewer explained:

The Sesotho children do experience these disorders, and they are sometimes missed because of the fact that they may be considered having a cultural connotation, and hence taken as normal if the child has difficulties with some of these.

Despite these positive features, an important and key theme was the omission of culturally based questions for Sesotho-speaking families such as their belief system and how that may affect or contribute to their diagnosis. These include witchcraft, ancestral worship or ceremonies. The omission of culturally based questions could call into question the validity of some disorders. Although schizophrenia was not a module selected for this review, several clinicians mentioned that symptoms (especially hallucinations and delusions) in Sesotho-speaking people may not always be seen as indicative of a psychological disorder, but could be identified as traditional gifts and a calling to become a traditional healer known as a “sangoma”. Symptoms mentioned above are most likely to be interpreted as an indication of ancestors’ way of communicating that attention should be given to traditional rituals and cultural ways by going to the school of prophets or traditional healers. Another example, which is more directly related to the DISC modules reviewed in this study, includes the cultural explanation of illness as being an inherited disorder or that it may be the result of incorrectly completed rituals:

this is typical behavior of children in this family or which the child took from the person he/she is named after. They would even go to the extent of blaming the clan traditions (“meetlo”) that were not done/or done wrongly, e.g. when a child is born there are traditional rituals they perform. Also they blame witchcraft; they would rather believe the sangoma/traditional doctor who will confirm their suspicion that the child is bewitched/possessed by evil spirit (thokolosi).

In addition, a question in the CD module relating to being mean or cruel to animals was identified as potentially creating false positives because for most of the Sesotho-speaking individuals actions such as killing such cited animals (pets, or include small animals such as rats, snakes, birds) could be seen as normative, and thus justifiable as part of the Sesotho culture. For instance, it will be quite acceptable for a boy of 10–11 years old to trap and kill certain birds, and this can even be encouraged in some instances. Similarly, asking about bad dreams was problematic in that

dreams are culturally believed and followed by some Sesotho speaking people. Thus it might be viewed in the light of a revelation of something bad that is going to happen. Thus the question might not be classified as a psychiatric problem.

Another cultural theme that emerged through the content analysis was the distance in parent–child relationships, especially regarding conduct problems such as lying, stealing or bullying. It was suggested by one respondent that parents or guardians not be asked about behaviors at school as they would not know or be aware of what happens at school. The involvement of teachers to answer questions of conduct problems and behavior at school is recommended. Alternatively, questions must be rephrased to ask parents whether they have had any complaints from school regarding behaviors.

Similarly, questions related to sexual behavior in adolescents were raised as a potential issue in administering the DISC:

Parents never want to admit that their children are at a stage in their life where they are sexually involved. So asking them about their children’s sexual involvement might make them uncomfortable or literally upset them, especially when the therapist is younger, the parents perceive him/her as disrespectful for asking them about sex-related matters.

Concern was also expressed about the DISC’s questioning regarding children or adolescents’ employment (e.g. delivering the Sunday paper). This was deemed confusing as “a child in this country is not expected to have found any form of employment”.

Several respondents mentioned the notion that psychiatric symptomatology expresses itself somatically in Sesotho populations. Although, as stated earlier, the DISC recognizes somatic symptomatology, it was felt that this could be taken further as depression and anxiety could be represented by headaches and stomach complaints in Sesotho culture.

Finally, the expert review did not require consideration of substance abuse problems, but reviewers felt that this was a growing and serious problem amongst Sesotho-speaking children (sniffing petrol and glue; alcohol; cigarette smoking) and should be included in any assessment of emotional-behavior problems in children.

Cultural norms regarding family structures and systems

Issues regarding family structure were raised. Since Sesotho-speaking children are often raised in child-headed families or live away from their parents who are deceased or working in another city, other children may be a significant source of attachment. This is omitted in the evaluation of GAD and SAD and it was recommended that it be included. In addition, given the importance of other children, it was recommended that a question be included in the depression module to assess for reduced social engagement in children as a marker of depression. Similarly, the interviewee needs to be asked about peers in the ODD module.

Related to the above, questions referring to “parents” were felt to be presented in a more “Westernized fashion” to the exclusion of extended family members. It was pointed out that not many African individuals live within a nuclear structure family. It was recommended that the DISC acknowledges the relevance and importance of extended family members such as grandparents, uncles and aunts to increase the cultural relevance of the test. This needs to be reviewed on a case-by-case basis due to significant variations in family structure. Two additional questions about care giving roles and sibling systems may provide adequate answers. Both of these are core to the notion of extended family systems and reference points.

Cultural norms regarding experience of time and memory

Although there was a recognition of the value of using a timeline to make diagnoses, there was a strongly felt need to take into account cultural differences in the understanding of time. As summarized by one respondent:

Most of the Sesotho speaking populations are not good with keeping track of their memories/life experiences as compared to other populations who from a very young age start to diarize their life experiences. This makes it difficult for Sesotho speaking people to recall clearly when asked about those past experiences. Also, most do not even celebrate any important dates like birthdays, anniversaries or they tend to forget them either. Most of the parents in the Sesotho populations do not even recall theirs’ or their children’s birthdays.

In the same vein another clinician noted that Sesotho-speaking people may have difficulty to count 4 weeks back from the current time. Four weeks may mean few weeks ago or just a week ago, especially if they are not educated.

Experience of time affects views on memory. For instance, a respondent pointed out a problem with asking about events like nightmares as a person can have nightmares but might not remember when they happened. Similarly, recall of other events are elicited in the DISC, but respondents noted that many of these events will not be remembered clearly, so being forced to answer yes/no in recalling these events within a time period places a limitation on the interviewee. The respondent suggested that a response option of “maybe” be included as this would allow interviewees to acknowledge that certain events may have occurred in the time period, but could not be precisely recalled. Generally, respondents felt that an over-reliance on a time frame to diagnose problems may lead to deception or simply an acknowledgement of failure to recall.

Other problems around quantification of symptoms to enable diagnosis were also raised, especially amongst less educated respondents. For instance, one of the conduct disorder questions requires parents to recall whether a child lied “more than ten times”. It was felt that a more general approach (e.g. “lied most of the time”) would be a better way of approaching the question.

Cultural norms regarding issues of gender

All respondents commented on cultural norms regarding the expression of emotion as it related to gender. In general, Sesotho-speaking populations were described as conservative and reluctant to seek psychological services. They were described as emotionally inexpressive, with difficulties in identifying and expressing feelings during interviews. With regard to men in particular, questions such as “Has he ever been very upset by seeing a dead body or seeing pictures of someone he knew well who is deceased?” may be more difficult to interpret as many men feel obliged to suppress their emotions:

Society expects the men/boys to be brave/to take up every challenge and never to cry or they are regarded as cowards/not man enough. To protect their male ego, most of the males tend to deny their fears, e.g. if a boy would be uncomfortable to be separated with his mother/father, it would be perceived abnormal and when the girl same age does the same, it would be normal and understandable. It is ok for a girl to be emotional and cry, but if a boy reacts the same way, something has to be wrong with him/to an extent that he can be labeled as a ‘sissy boy’. These kinds of labels make the males most negative towards therapy or to not be truthful to the therapist about their feeling/emotions or the suicidal ideations.

Questions in the anxiety module relating to somatic symptoms like headaches and stomach aches needed to consider the role of menstruation in girls, which could cause the same symptoms. This issue was also raised regarding the feelings of sadness and unhappiness, which occur around menstruation.

Several respondents warned that questions on sexuality are very sensitive and not openly discussed in the Sesotho culture or family and thus any questions related to sexuality should be handled with care. If such questions are included they may be better done by matching the gender of the interviewer with the interviewee.

Language problems

A range of language problems were listed by the respondents. Overall, respondents agreed that unless the DISC is translated into Sesotho, it can only be administered to those that are fluent in English. While clinicians acknowledged that most words and phrases could be successfully translated into Sesotho, those that are difficult to translate into Sesotho include: getting mugged, grouchy, jumpy, butt, fidgety, sudden attack, throw up, keyed up, bad accident, difficulty at keeping one’s mind on what one was doing, sleeping disturbances, disorganized, mad, bat (as weapon), tense, anxious, upset, uncomfortable, relax, aches and pains, sad, unhappy, depressed, irritable, bad mood, hyperactive, overactive, restless, jiggling, blurt, temper, and suffocating.

In addition, questions that may pose special challenges are ones where neighboring expressions for feelings are used in the same question, e.g. “Did being sad or depressed seem to make her feel bad or seem to make her feel upset?” It was pointed out that in Sesotho there are not enough words to differentiate these feelings. Feeling bad, upset and sad, have the same meaning in Sesotho (“Ho hlonama”). One potential solution posed here was to use metaphor or descriptions so the person could understand the term, but this would take up a lot more space and time.

One key concern raised was the different language basis between English and Sesotho. Part of this would require simplifying the language of the questions and the constructs within them:

In order to get accurate and satisfactory results, pertaining to emotional-behavior problems, from Sesotho speaking candidates, one must realize that the Sesotho and the English vocabularies are completely different, therefore the wording is interpreted differently. Questions must be made easy, understandable and less educational.

Levels of sophistication of population, by education and urbanization

All respondents raised the educational level and the environment where people live (rural vs. urban) as a major issue in the administration of the DISC, especially with regard to the computerized nature of the DISC. Respondents pointed out that most of the Sesotho-speaking populations are still illiterate especially in rural areas. At one extreme one respondent said:

Most of the illiterate and rural people would not understand that the computers are programmed by men. They would think that the computer diagnose them and not the therapist using it. This would make some of them to doubt the results of the computerized DISC.

Clinicians agreed that Sesotho people may prefer a simpler and familiar method of interview such as one-on-one talk where eye contact can be maintained throughout the interview. Most importantly, the self-report or voice DISC was not recommended for use.

Even if a paper version is used, several issues were highlighted by respondents if the DISC is used in rural settings. First, interviewers should be given the liberty to explain the questions in simpler terms to ensure more accurate responses. Against this background, the clinicians emphasized adequate training in the administration of the DISC, as interviewers will have to be able to accurately describe concepts to interviewees. This would put limitations on lay interviewers administering the instrument.

Discussion and conclusion

With the abolition of apartheid in South Africa, and the acknowledgement that the mental health of the majority of South Africans was ignored for many years, research into the cultural appropriateness of measures in South Africa is of prime importance. The current study is the first to evaluate the DISC for its sociocultural appropriateness for use in South Africa and in Sesotho-speaking populations. Some of the most important reasons for adapting diagnostic tools include the enhancement of fairness in assessment, the reduction in costs (it is cheaper and quicker to adapt an already existing tool), facilitation of comparative studies between different language and cultural groups and the comparison of newly developed measures to existing norms, interpretations and other available information [10]. In addition, the development of psychiatric tools is crucial for the early identification and intervention of children with emotional-behavior disorders in South Africa, especially against the background of growing numbers of parental deaths associated with HIV/AIDS, which places these children at high risk for the development of emotional-behavior problems [21] (D. Skinner, C. Sharp, S. Jooste, J. Kleintjies, A comparison of orphans and non-orphans on key criteria of vulnerability in two municipalities in South Africa, in preparation).

Notwithstanding the necessary limitations associated with qualitative methodology, the current study has confirmed the potential of the DISC for use in large-scale psychiatric epidemiology research studies in South Africa, as well as in clinical settings. It offers a comprehensive standardized way to systematically assess children and is quick and easy to administer. In addition to confirming the use of the DISC in Sesotho populations, it is also of note that Sesotho clinicians by and large supported the DSM-IV diagnostic classification system. Clinicians were explicitly asked to comment on the categorization of phenomena as either pathological or non-pathological in the Sesotho context as well as the content or clustering of pathological symptoms among Sotho-speaking children and adolescents. As discussed above, clinicians thought that the DSM categorization of symptoms were relevant and appropriate, and even pointed out that a disregard for a DSM approach to diagnosis may lead to under-diagnosis of problems in children.

The clinicians’ acceptance of the DSM classification system may be explained by the fact that clinicians at South African universities (especially clinical psychologists) are trained in a scientist-practitioner and medical model. Judgments about the standard of care are therefore informed by scientific research and a Western model of mental illness. It is therefore possible that through their training, Sesotho clinicians are biased towards accepting the worldview and methods of the DISC. Discordance between clinicians’ views and lay expectations is common in Western [22] and non-Western [23] countries. To bridge this gap, an integration of traditional healing practices into the health care system has also been proposed in the South African context [24].

While clinicians generally supported the DSM classification system on which the DISC has been based, several problems with associated recommendations for further cultural adaptation, emerged through this study. First, it is clear that the DISC requires both cultural adaptation and translation into Sesotho to address Americanisms, problems in interpretation due to the adversity children live under, language problems, the effect of rural settings and education level, and cultural norms regarding psychiatric symptoms, gender, the experience of time, the expression of emotion, and family structure. A back-translation design [25] will not only solve many of the language problems identified by clinician reviewers, but will also address the many sociocultural issues raised by reformulating questions in a culturally sensitive way. It was clear that a translation would also necessitate simplifying questions.

Second, the full DISC is seen as too lengthy for administration in this population. While it is a limitation of the current study that clinicians were not explicitly asked to comment on the usefulness of the DISC for research settings, we recommend here, like Robertson et al. [7], that relevant modules be chosen for research (and even clinical) administration instead of the full DISC. Selection should include the substance abuse module of the DISC. In addition, the computerized version of the DISC should not be used in rural areas, but should be replaced by a paper version.

Third, it is important that cultural explanations for psychiatric problems are respected. This may be achieved partly by offering the opportunity during the interview for narrative descriptions beyond the binary yes/no answering format. This may, however, challenge the basic implementation of the tool as a structured interview. On some questions some additional level of sensitivity may be required, such as on questions of sexual contact and emotional expression for boys.

In conclusion, this paper has illustrated how crucial it is to assess a Western psychiatric tool for its cultural appropriateness before using it. At the same time, we aimed at providing an initial impetus for the elaboration of Westernized child psychiatric instruments in Black children in South Africa. The urgent need for reliable and valid psychiatric tools in countries like South Africa needs to be balanced with the need for culturally sensitive and appropriate measures. Given the qualitative nature of this study, an important next step would be a quantitative study of external validity with clinician diagnosis as criterion measure. Despite the uniqueness of each African language spoken in South Africa and other sub-Saharan countries, many of the issues raised here with regard to a Sesotho version of the DISC are likely to have relevance to translation of the DISC into other related languages, or indeed to the social, economic, familial, and cultural conditions occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a National Institute of Health Centers for AIDS research developmental grant awarded to Carla Sharp while at Baylor College of Medicine.

Contributor Information

Carla Sharp, Email: csharp2@uh.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77024, USA.

Donald Skinner, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Motsaathebe Serekoane, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Michael W. Ross, University of Texas, Houston, USA

References

- 1.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. In: Hersen M, Thomas JC, Goldstein G, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. Wiley; New York: 2003. pp. 256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Atlas: mapping mental health resources in the world. WHO; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lund C, Flisher AJ. Norms for mental health services in South Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(7):587–594. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0057-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson I. Primary level psychological services in South Africa: can a new psychological professional fill the gap? Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(1):33–40. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botha UA, Koen L, Niehaus DJ. Perceptions of a South African schizophrenia population with regards to community attitudes towards their illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(8):619–623. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(1):57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasan AD, Neufeld K, Jayaram G. Practice patterns and treatment choices among psychiatrists in New Delhi, India: a qualitative and quantitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(2):109–119. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0408-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foxcroft C, Roodt G, Abrahams F. The practice of psychological assessment. In: Foxcroft C, Roodt G, editors. Introduction to psychological assessment in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanjee A. Cross-cultural test adaptation and translation. In: Foxcroft C, Roodt G, editors. An introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mels C, Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Rosseel Y. Community-based cross-cultural adaptation of mental health measures in emergency settings: validating the IES-R and HSCL-37A in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ensink K, Robertson BA, Zissis C, Leger P, De Jager W. Conduct disorder among children in an informal settlement. Evaluation of an intervention programme. S Afr Med J. 1997;87(11):1533–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson BA, Ensink K, Parry CDH, Chalton D. Performance of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) in an informal settlement area in South Africa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(9):1156–1164. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. SAGE publications; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner D. Qualitative methodology: an introduction. In: Ehrlich R, Joubert G, editors. A manual for South Africa. 2. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics South Africa. 2007 Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/

- 17.Lohr H. Sampling: design and analysis. Duxbury Press; Pacific Grove: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mels C, Derluyn I, Broekaert E. Social support in unaccompanied asylum-seeking boys: a case study. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(6):757–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simbayi LC, Skinner D, Letlape L, Zuma K. Workplace policies in public education: a review focusing on HIV/AIDS. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubio-Stipec M, Canino I, Hsiao-Rei Hicks M, Tsuang MT. Cultural factors influencing the selection, use, and interpretation of psychiatric measures. In: Rush J, First MB, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(8):755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dejman M, Forouzan A, Assari S, Farahani MA, MalekAfzali H, Rostami AF, et al. Clinicians’ view of experience of assessing and following up depression among women in IR Iran. World Cult Psychiatry Res Rev. 2009;4(2):74–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swartz L. Culture and mental health: a Southern African view. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brislin R. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WL, Berry JW, editors. Field methods in cross-cultural research. SAGE; Newbury Park: 1986. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]