Abstract

One hundred and five generic types of Pleosporales are described and illustrated. A brief introduction and detailed history with short notes on morphology, molecular phylogeny as well as a general conclusion of each genus are provided. For those genera where the type or a representative specimen is unavailable, a brief note is given. Altogether 174 genera of Pleosporales are treated. Phaeotrichaceae as well as Kriegeriella, Zeuctomorpha and Muroia are excluded from Pleosporales. Based on the multigene phylogenetic analysis, the suborder Massarineae is emended to accommodate five families, viz. Lentitheciaceae, Massarinaceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae and Trematosphaeriaceae.

Keywords: Generic type, Massarineae, Molecular phylogeny, Morphology, Pleosporales, Taxonomy

Introduction

Historic overview of Pleosporales

Pleosporales is the largest order in the Dothideomycetes, comprising a quarter of all dothideomycetous species (Kirk et al. 2008). Species in this order occur in various habitats, and can be epiphytes, endophytes or parasites of living leaves or stems, hyperparasites on fungi or insects, lichenized, or are saprobes of dead plant stems, leaves or bark (Kruys et al. 2006; Ramesh 2003).

The Pleosporaceae was introduced by Nitschke (1869), and was assigned to Sphaeriales based on immersed ascomata and presence of pseudoparaphyses (Ellis and Everhart 1892; Lindau 1897; Wehmeyer 1975; Winter 1887). Taxa in this family were then assigned to Pseudosphaeriaceae (Theissen and Sydow 1918; Wehmeyer 1975). Pseudosphaeriales, represented by Pseudosphaeriaceae, was introduced by Theissen and Sydow (1918), and was distinguished from Dothideales by its uniloculate, perithecioid ascostromata. Subsequently, the uni- or pluri-loculate ascostromata was reported to be an invalid character to separate members of Dothideomycetes into different orders (Luttrell 1955). In addition, the familial type of Pseudosphaeriales together with its type genus, Pseudosphaeria, was transferred to Dothideales, thus Pseudosphaeriales became a synonym of Dothideales. The name “Pseudosphaeriales” has been applied in different senses, thus Pleosporales (as an invalid name due to the absence of a Latin diagnosis) was proposed by Luttrell (1955) to replace the confusing name, Pseudosphaeriales, which included seven families, i.e. Botryosphaeriaceae, Didymosphaeriaceae, Herpotrichiellaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Mesnieraceae, Pleosporaceae and Venturiaceae. Müller and von Arx (1962) however, reused Pseudosphaeriales with 12 families included, viz. Capnodiaceae, Chaetothyriaceae, Dimeriaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Mesnieraceae, Micropeltaceae, Microthyriaceae, Mycosphaerellaceae, Pleosporaceae, Sporormiaceae, Trichothyriaceae and Venturiaceae.

Familial circumscriptions of the Pleosporales were based on characters of ascomata, morphology of asci and their arrangement in locules, presence and type of hamathecium, shape of papilla or ostioles, morphology of ascospores and type of habitats (Luttrell 1973) (Table 1). Based on these characters, Luttrell (1973) included eight families, i.e. Botryosphaeriaceae, Dimeriaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Mesnieraceae, Mycoporaceae, Pleosporaceae, Sporormiaceae and Venturiaceae in Pleosporales. In their review of bitunicate ascomycetes, von Arx and Müller (1975) accepted only a single order, Dothideales, with two suborders, i.e. Dothideineae (including Atichiales, Dothiorales, Hysteriales and Myriangiales) and Pseudosphaeriineae (including Capnodiales, Chaetothyriales, Hemisphaeriales, Lophiostomatales, Microthyriales, Perisporiales, Pleosporales, Pseudosphaeriales and Trichothyriales). This proposal has however, rarely been followed. Three existing families, i.e. Lophiostomataceae, Pleosporaceae and Venturiaceae plus 11 other families were accepted in Pleosporales as arranged by Barr (1979a) (largely using Luttrell’s concepts, Table 1), and she assigned these families to six suborders. The morphology of pseudoparaphyses was given much prominence at the ordinal level in this classification (Barr 1983). In particular the Melanommatales was introduced to accommodate taxa with trabeculate pseudoparaphyses (Sporormia-type centrum development) (Barr 1983), distinguished from cellular pseudoparaphyses (Pleospora-type centrum development) possessed by members of Pleosporales sensu Barr. The order Melanommatales included Didymosphaeriaceae, Fenestellaceae, Massariaceae, Melanommataceae, Microthyriaceae, Mytilinidiaceae, Platystomaceae and Requienellaceae (Barr 1990a).

Table 1.

Major circumscription changes of Pleosporales from 1955 to 2011

| References | Circumscription of Pleosporales |

|---|---|

| Luttrell 1955 | Pleospora-type centrum development. |

| Müller and von Arx 1962 | Ascomata perithecoid, with rounded or slit-like ostiole; asci produced within a locule, arranged regularly in a single layer or irregularly scattered, surrounded with filiform pseudoparaphyses, cylindrical, ellipsoidal or sac-like. |

| Luttrell 1973 | Ascocarps perithecioid, immersed, erumpent to superficial on various substrates, asci ovoid to mostly clavate or cylindrical, interspersed with pseudoparaphyses (sometimes form an epithecium) in mostly medium- to large-sized locules. |

| Barr 1979a | Saprobic, parasitic, lichenized or hypersaprobic. Ascomata perithecioid, rarely cleistothecioid or hysterothecioid, peridium pseudoparenchymatous, pseudoparaphyses cellular, narrow or broad, deliquescing early at times, not forming an epithecium, asci oblong, clavate or cylindrical, interspersed with pseudoparaphyses, ascospores mostly asymmetric. |

| Barr 1987b | Saprobic, biotrophic or hemibiotrophic. Ascomata globose, subglobose or conical, asci bitunicate, oblong, clavate or cylindrical, cellular pseudoparaphyses, ascospores hyaline or pigmented, asymmetric or symmetric, with or without septa. |

| Kirk et al. 2001, 2008 | Ascomata perithecial or rarely cleistothecial, sometimes clypeate, mostly globose, thick-walled, immersed or erumpent, black, sometimes setose, peridium composed of pseudoparenchymatous cells, pseudoparaphyses trabeculate or cellular, asci cylindrical, fissitunicate, with a well-developed ocular chamber, rarely with a poorly defined ring (J-), ascospores hyaline to brown, septate, thin or thick-walled, sometimes muriform, usually with sheath, anamorphs hyphomycetous or coelomycetous. |

| Boehm et al. 2009a, b; Mugambi and Huhndorf 2009b; Schoch et al. 2009; Shearer et al. 2009; Suetrong et al. 2009; Tanaka et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009a | Hemibiotrophic, saprobic, hypersaprobic, or lichenized. Habitats in freshwater, marine or terrestrial environment. Ascomata perithecioid, rarely cleistothecioid, immersed, erumpent to superficial, globose to subglobose, or lenticular to irregular, with or without conspicuous papilla or ostioles. Ostioles with or without periphyses. Peridium usually composed of a few layers of cells with various shapes and structures. Hamathecium persistent, filamentous, very rarely decomposing. Asci bitunicate, fissitunicate, cylindrical, clavate to obclavate, with or without pedicel. Ascospores hyaline or pigmented, ellipsoidal, broadly to narrowly fusoid or filiform, mostly septate. |

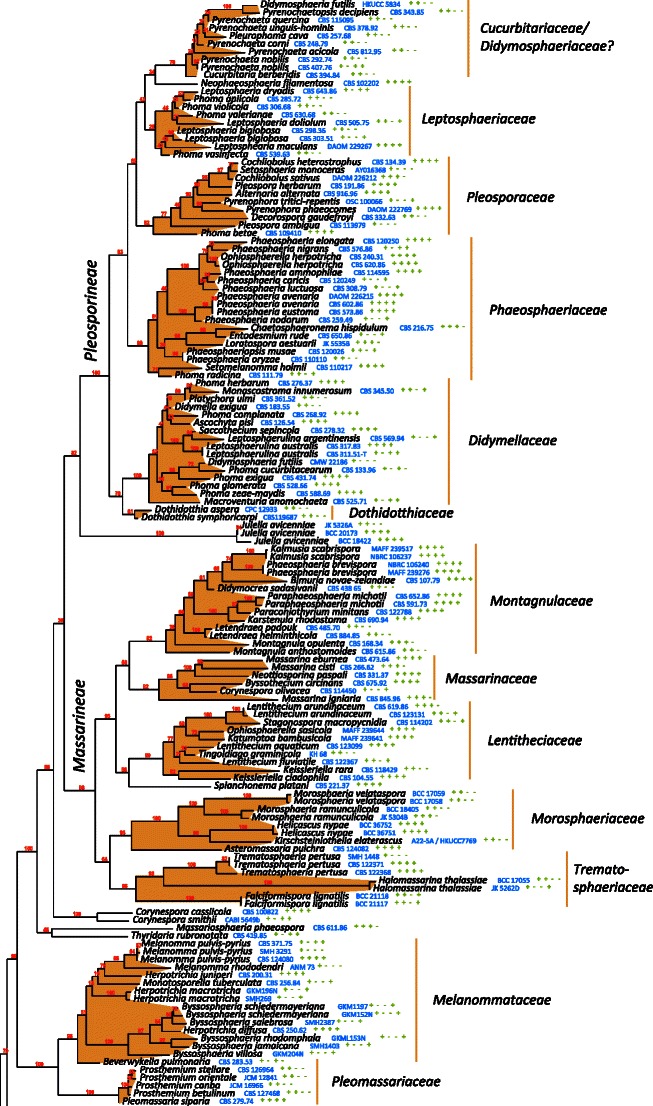

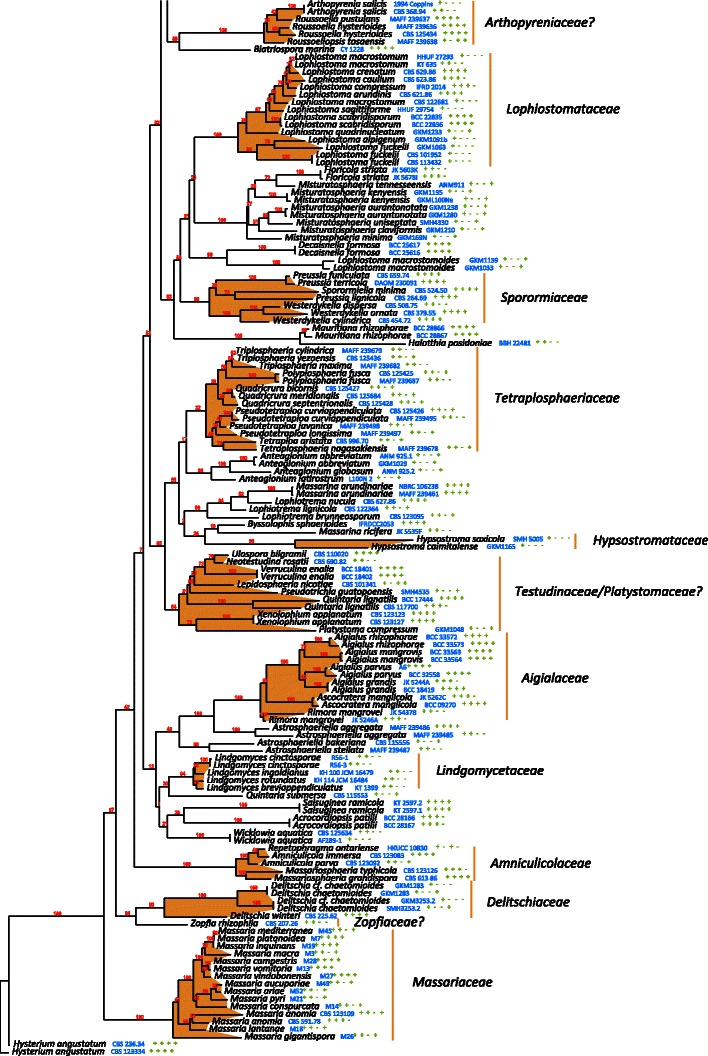

Pleosporales was formally established by Luttrell and Barr (in Barr 1987b), characterised by perithecioid ascomata, usually with a papillate apex, ostioles with or without periphyses, presence of cellular pseudoparaphyses, bitunicate asci, and ascospores of various shapes, pigmentation and septation (Table 1). Eighteen families were included, i.e. Arthopyreniaceae, Botryosphaeriaceae, Cucurbitariaceae, Dacampiaceae, Dimeriaceae, Hysteriaceae, Leptosphaeriaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Parodiellaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae, Phaeotrichaceae, Pleomassariaceae, Pleosporaceae, Polystomellaceae, Pyrenophoraceae, Micropeltidaceae, Tubeufiaceae and Venturiaceae. Recent phylogenetic analysis based on DNA sequence comparisons, however, indicated that separation of the orders (Pleosporales and Melanommatales) based on the Pleospora or Sporormia centrum type, is not a natural grouping, and Melanommatales has therefore been combined under Pleosporales (Liew et al. 2000; Lumbsch and Lindemuth 2001; Reynolds 1991). Six more families, i.e. Cucurbitariaceae, Diademaceae, Didymosphaeriaceae, Mytilinidiaceae, Testudinaceae and Zopfiaceae, were subsequently added to Pleosporales (Lumbsch and Huhndorf 2007). After intensive sampling and multigene phylogenetic studies, 20 families were accepted in Pleosporales, namely Aigialaceae, Amniculicolaceae, Delitschiaceae, Didymellaceae, Didymosphaeriaceae, Hypsostromataceae, Lentitheciaceae, Leptosphaeriaceae, Lindgomycetaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Massarinaceae, Melanommataceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae, Pleosporaceae, Pleomassariaceae, Sporormiaceae, Tetraplosphaeriaceae and Trematosphaeriaceae (Boehm et al. 2009a, b; Mugambi and Huhndorf 2009b; Schoch et al. 2009; Shearer et al. 2009; Suetrong et al. 2009; Tanaka et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009a) (Table 1). In addition, another five families, i.e. Arthopyreniaceae, Cucurbitariaceae, Diademaceae, Teichosporaceae and Zopfiaceae are tentatively included (Kruys et al. 2006; Plate 1). In the most recent issue of Myconet, 28 families were included in Pleosporales (Lumbsch and Huhndorf 2010).

Plate 1.

The best scoring likelihood tree of representative Pleosporales obtained with RAxML v. 7.2.7 for a concatenated set of nucleotides from LSU, SSU, RPB2 and TEF1. Family and suborder names are indicated where possible. The percentages of nodes present in 250 bootstrap pseudo replicates are shown above branches. Culture and voucher numbers are indicated after species names and the presence of the genes used in the analysis are indicated by pluses in this order: LSU, SSU, RPB2, TEF1

Species included in Pleosporales have different ecological or morphological characters. For instance, members of the Leptosphaeriaceae have saprobic or parasitic lifestyles and lightly pigmented, multi-septate ascospores. Members of the Lophiostomataceae are mostly saprobic with ascomata that usually possess a compressed apex. Members of Sporormiaceae are coprophilous, and are characterized by heavily pigmented, multi-septate ascospores with germ slits, and with or without non-periphysate ostioles. The lack of DNA sequence data for representatives of numerous families means that their inter-relationships are unclear and many genera or species are artificially placed based on morphological classification. The most recent study on Venturiaceae indicated that this group had a set of unique morphological and ecological characters, which is distinct and distantly related to other members of Pleosporales (Kruys et al. 2006; Zhang et al. unpublished). Molecular phylogenetic results indicated that members of Venturiaceae form a robust clade separate from the core members of Pleosporales, and the clade of Venturiaceae was uncertainly placed but outside of the two currently designated dothideomycetous subclasses, i.e. Pleosporomycetidae and Dothideomycetidae (Schoch et al. 2009). In addition, phylogenetic analysis of rDNA sequence data indicates that members of Zopfiaceae (as Testudinaceae) seem to lack affinity with Pleosporales (Kodsueb et al. 2006 b). Thus, 26 families are temporarily accepted in Pleosporales in this study, although some such as Zopfiaceae, still require extensive DNA sequence sampling (Table 4).

Table 4.

Families currently accepted in Pleosporales (syn. Melanommatales) with included genera

| Pleosporales subordo. Pleosporineae |

| ?Cucurbitariaceae |

| Cucurbitaria Gray |

| Curreya Sacc. |

| ?Rhytidiella Zalasky |

| Syncarpella Theiss. & Syd. |

| Didymellaceae |

| Didymella Sacc. ex D. Sacc. |

| Didymosphaerella Cooke |

| Leptosphaerulina McAlpine |

| Macroventuria Aa |

| ?Platychora Petr. |

| Didymosphaeriaceae |

| Appendispora K.D. Hyde |

| Didymosphaeria Fuckel |

| Phaeodothis Syd. & P. Syd. |

| Dothidotthiaceae |

| Dothidotthia Höhn. |

| Leptosphaeriaceae |

| Leptosphaeria Ces. & De Not. |

| Neophaeosphaeria Câmara, M.E. Palm & A.W. Ramaley |

| Phaeosphaeriaceae |

| Barria Z.Q. Yuan |

| Bricookea M.E. Barr |

| ?Chaetoplea (Sacc.) Clem. |

| ?Eudarluca Speg. |

| Entodesmium Reiss |

| Hadrospora Boise |

| Lautitia S. Schatz |

| Loratospora Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Metameris Theiss. & Syd. |

| Mixtura O.E. Erikss. & J.Z. Yue |

| Nodulosphaeria Rabenh. |

| Ophiobolus Reiss |

| Ophiosphaerella Speg. |

| Phaeosphaeria I. Miyake |

| Phaeosphaeriopsis Câmara, M.E. Palm & A.W. |

| Ramaley |

| Pleoseptum A.W. Ramaley & M.E. Barr |

| Setomelanomma M. Morelet |

| Wilmia Dianese, Inácio & Dornelo-Silva |

| Pleosporaceae |

| Cochliobolus Drechsler |

| Crivellia Shoemaker & Inderbitzin |

| Decorospora Inderbitzin, Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Extrawettsteinina M.E. Barr |

| Lewia M.E. Barr & E.G. Simmons |

| Macrospora Fuckel |

| Platysporoides (Wehm.) Shoemaker & C.E. Babc. |

| Pleospora Rabenh. ex Ces. & De Not. |

| Pseudoyuconia Lar. N. Vasiljeva |

| Pyrenophora Fr. |

| Setosphaeria K.J. Leonard & Suggs |

| Pleosporales subordo. Massarineae |

| Lentitheciaceae |

| Lentithecium K.D. Hyde, J. Fourn. & Yin. Zhang |

| Katumotoa Kaz. Tanaka & Y. Harada |

| Keissleriella Höhn. |

| ?Wettsteinina Höhn. |

| Massarinaceae |

| Byssothecium Fuckel |

| Massarina Sacc. |

| Saccharicola D. Hawksw. & O.E. Erikss. |

| Montagnulaceae |

| Bimuria D. Hawksw., Chea & Sheridan |

| ?Didymocrea Kowalsky |

| Kalmusia Niessl |

| Karstenula Speg. |

| Letendraea Sacc. |

| Montagnula Berl. |

| Paraphaeosphaeria O.E. Erikss. |

| Tremateia Kohlm., Volkm.-Kohlm. & O.E. Erikss. |

| Morosphaeriaceae |

| ?Asteromassaria Höhn |

| Helicascus Kohlm. |

| Morosphaeria Suetrong, Sakay., E.B.G. Jones & C.L. Schoch |

| Trematosphaeriaceae |

| Falciformispora K.D. Hyde |

| Halomassarina Suetrong, Sakay., E.B.G. Jones, Kohlm., Volkm.-Kohlm. & C.L. Schoch |

| Trematosphaeria Fuckel |

| Other families |

| Aigialaceae |

| Aigialus S. Schatz & Kohlm. |

| Ascocratera Kohlm. |

| Rimora Kohlm., Volkm.-Kohlm., Suetrong, Sakay. & E.B.G. Jones |

| Amniculicolaceae |

| Amniculicola Y. Zhang & K.D. Hyde |

| Murispora Yin. Zhang, C.L. Schoch, J. Fourn., Crous & K.D. Hyde |

| Massariosphaeria (E. Müll.) Crivelli |

| Neomassariosphaeria Yin. Zhang, J. Fourn. & K.D. Hyde |

| ?Arthopyreniaceae (Massariaceae) |

| Arthopyrenia A. Massal. |

| Dothivalsaria Petr. |

| ?Dubitatio Speg. |

| Massaria De Not. |

| Navicella Fabre |

| Roussoëlla Sacc. |

| ?Roussoellopsis I. Hino & Katum. |

| Delitschiaceae |

| Delitschia Auersw. |

| Ohleriella Earle |

| Semidelitschia Cain & Luck-Allen |

| ?Diademaceae |

| Clathrospora Rabenh. |

| Comoclathris Clem. |

| Diadema Shoemaker & C.E. Babc. |

| Diademosa Shoemaker & C.E. Babc. |

| Graphyllium Clem. |

| Hypsostromataceae |

| Hypsostroma Huhndorf |

| Lindgomycetaceae |

| Lindgomyces K. Hirayama, Kaz. Tanaka & Shearer 2010 |

| Lophiostomataceae |

| Lophiostoma Ces. & De Not. |

| Melanommataceae |

| ?Astrosphaeriella Syd. & P. Syd. (Syn. Javaria) |

| ?Anomalemma Sivan. |

| ?Asymmetricospora J. Fröhl. & K.D. Hyde |

| Bertiella (Sacc.) Sacc. & P. Syd. |

| Bicrouania Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Byssosphaeria Cooke |

| Calyptronectria Speg. |

| ?Caryosporella Kohlm. |

| Herpotrichia Fuckel |

| ?Mamillisphaeria K.D. Hyde, S.W. Wong & E.B.G. Jones |

| Melanomma Nitschke ex Fuckel |

| Ohleria Fuckel |

| Pseudotrichia Kirschst. |

| Pleomassariaceae |

| ?Lichenopyrenis Calatayud, Sanz & Aptroot |

| ?Splanchnonema Corda |

| ?Peridiothelia D. Hawksw. |

| Pleomassaria Speg. |

| Sporormiaceae |

| Chaetopreussia Locq.-Lin. |

| Eremodothis Arx |

| Pleophragmia Fuckel |

| Preussia Fuckel |

| Pycnidiophora Clum |

| Sporormia De Not. |

| Sporormiella Ellis & Everh. |

| Spororminula Arx & Aa |

| Westerdykella Stolk |

| ?Teichosporaceae |

| Chaetomastia (Sacc.) Berl |

| Immotthia M.E. Barr |

| Loculohypoxylon M.E. Barr |

| Sinodidymella J.Z. Yue & O.E. Erikss. |

| Teichospora Fuckel |

| Tetraplosphaeriaceae |

| Polyplosphaeria Kaz. Tanaka & K. Hirayama |

| Tetraplosphaeria Kaz. Tanaka & K. Hirayama |

| Triplosphaeria Kaz. Tanaka & K. Hirayama |

| ?Zopfiaceae (syn Testudinaceae) |

| Caryospora De Not. |

| Celtidia J.M. Janse |

| ?Coronopapilla Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Halotthia Kohlm. |

| Lepidosphaeria Parg.-Leduc |

| Mauritiana Poonyth, K.D. Hyde, Aptroot & Peerally |

| Pontoporeia Kohlm. |

| ?Rechingeriella Petr. |

| Richonia Boud. |

| Testudina Bizz. |

| Ulospora D. Hawksw., Malloch & Sivan. |

| Zopfia Rabenh. |

| Zopfiofoveola D. Hawksw. |

| Pleosporales genera incertae sedis |

| Acrocordiopsis Borse & K.D. Hyde |

| Aglaospora De Not. |

| Anteaglonium Mugambi & Huhndorf |

| Ascorhombispora L. Cai & K.D. Hyde |

| Atradidymella Davey & Currah |

| Biatriospora K.D. Hyde & Borse |

| Byssolophis Clem. |

| Carinispora K.D. Hyde |

| Cilioplea Munk |

| Decaisnella Fabre |

| Epiphegia Nitschke ex G.H. Otth |

| Julella Fabre |

| Lineolata Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Lophiella Sacc. |

| Lophionema Sacc. |

| Lophiotrema Sacc. |

| Neotestudina Segretain & Destombes |

| Ostropella (Sacc.) Höhn. |

| Paraliomyces Kohlm. |

| Passeriniella Berl. |

| ?Isthmosporella Shearer & Crane |

| Quintaria Kohlm. & Volkm.-Kohlm. |

| Saccothecium Fr. |

| Salsuginea K.D. Hyde |

| Shiraia P. Henn. |

| Xenolophium Syd. |

| Family excluded |

| Phaeotrichaceae |

| Echinoascotheca Matsush. |

| Phaeotrichum Cain & M.E. Barr |

| Trichodelitschia Munk |

| Genera excluded |

| Kriegeriella Höhn. |

| Muroia I. Hino & Katum. |

| Zeuctomorpha Sivan., P.M. Kirk & Govindu |

Morpho-characters used in taxonomy of Pleosporales

Sexual characters

According to the Linnean classification system, reproductive structures are the most important criteria in plant taxonomy, and this proposal is widely applied in fungal taxonomy (Gäumann 1952). In the classification of Dothideomycetes, reproductive characters such as the uni- or multilocular nature and shape of ascomata, presence and shape of ostioles/papillae, shape and apical structures of asci and shape, pigmentation and septation of ascospores play important roles at different ranks (Clements and Shear 1931; Luttrell 1951, 1955, 1973). Besides the common morphological characters possessed by Dothideomycetes (bitunicate and fissitunicate asci as well as the perithecioid-like ascostromata), most pleosporalean fungi also have pseudoparaphyses among their well-arranged asci (Zhang et al. 2009a). Currently, classification of Pleosporales at the family level focuses mostly on morphological characters of ascomata (such as size, shape of ostiole or papilla), presence or absence of periphyses, characters of centrum (such as asci, pseudoparaphyses and ascospores) as well as on lifestyle or habitat (Barr 1990a; Shearer et al. 2009; Suetrong et al. 2009; Tanaka et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009a), whilst relying extensively on DNA sequence comparisons.

Ascomata

Most species of Pleosporales have uniloculate ascomata. The presence (or absence) and forms of papilla and ostiole are the pitoval character of ascomata, which serve as important characteristics in generic or higher rank classification (Clements and Shear 1931). The vertically flattened papilla has recently been shown as an effective criterion for familial level classification, e.g. in the Amniculicolaceae and the Lophiostomataceae (Zhang et al. 2009a). Papillae and ostioles are present in most species of Pleosporales, except in the Diademaceae and Sporormiaceae. Members of Diademaceae have apothecial ascomata, and some genera of Sporormiaceae have cleistothecioid ascomata. Another coprophilous pleosporalean family, Delitschiaceae, can be distinguished from Sporormiaceae by the presence of periphysate ostioles.

Pseudoparaphyses

Presence of pseudoparaphyses is a characteristic of Pleosporales (Kirk et al. 2008; Liew et al. 2000). Although pseudoparaphyses may be deliquescing in some families when the ascomata mature (e.g. in Didymellaceae), they are persistent in most of other pleosporalean members. According to the thickness, with or without branching and density of septa, pseudoparaphyses were roughly divided into two types: trabeculate and cellular, and their taxonomic significance need to be re-evaluated (Liew et al. 2000).

Asci

The asci of Pleosporales are bitunicate, usually fissitunicate, mostly cylindrical, clavate or cylindro-clavate, and rarely somewhat obclavate or sphaerical (e.g. Macroventuria anomochaeta Aa and Westerdykella dispersa). There are ocular chambers in some genera (e.g. Amniculicola and Asteromassaria), or sometimes with a large apical ring (J-) (e.g. Massaria).

Ascospores

Ascospores of Pleosporales can be hyaline or colored to varying degrees. They may be amerosporous (e.g. species of Semidelitschia), phragmosporous (e.g. Phaeosphaeria and Massariosphaeria), dictyosporous (e.g. most species of Pleospora and Bimuria), or scolecosporous (e.g. type species of Cochliobolus, Entodesmium or Lophionema). Although ascospore morphology had been regarded as a key factor in differentiating genera under some families, e.g. Arthopyreniaceae (Watson 1929) and Testudinaceae (Hawksworth 1979), it has been proven variable even within a single species. For instance, two types of ascospores are produced by Mamillisphaeria dimorphospora, i.e. one type is large and hyaline, and the other is comparatively smaller and brown. Numerous studies have shown the unreliability of ascospore characters above genus level classification (e.g. Phillips et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009a).

Asexual states of Pleosporales

Anamorphs of pleosporalean families

Anamorphs of Pleosporales are mostly coelomycetous, but may also be hyphomycetous. Phoma or Phoma-like anamorphic stages and its relatives are most common anamorphs of Pleosporales (Aveskamp et al. 2010; de Gruyter et al. 2009, 2010; Hyde et al. 2011). Some of the reported teleomorph and anamorph connections (including some listed below) are, however, based on the association rather than single ascospore isolation followed by induction of the other stage in culture (Hyde et al. 2011).

Pleosporales suborder Pleosporineae

Pleosporineae is a phylogenetically well supported suborder of Pleosporales, which temporarily includes seven families, namely Cucurbitariaceae, Didymellaceae, Didymosphaeriaceae, Dothidotthiaceae, Leptosphaeriaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae and Pleosporaceae, and contains many important plant pathogens (de Gruyter et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2009a). De Gruyter et al. (2009, 2010) systematically analyzed the phylogeny of Phoma and its closely related genera, and indicated that their representative species cluster in different subclades of Pleosporineae.

Cucurbitariaceae

Based on the molecular phylogenetic analysis, some species of Coniothyrium, Pyrenochaeta, Phoma, Phialophorophoma and Pleurophoma belong to Cucurbitariaceae (de Gruyter et al. 2010; Hyde et al. 2011). Other reported anamorphs of Cucurbitaria are Camarosporium, Diplodia-like and Pleurostromella (Hyde et al. 2011; Sivanesan 1984). The generic type of Cucurbitaria (C. berberidis Fuckel) is linked to Pyrenochaeta berberidis (Farr et al. 1989). Curreya has a Coniothyrium-like anamorphic stage (von Arx and van der Aa 1983; Marincowitz et al. 2008). The generic type of Curreya is C. conorum (Fuckel) Sacc., which is reported to be linked with Coniothyrium glomerulatum Sacc. (von Arx and van der Aa 1983). The generic type of Rhytidiella (R. moriformis, Cucurbitariaceae) can cause rough-bark of Populus balsamifera, and has a Phaeoseptoria anamorphic stage (Zalasky 1968). Rhytidiella baranyayi Funk & Zalasky, another species of Rhytidiella associated with the cork-bark disease of aspen is linked with Pseudosporella-like anamorphs (Funk and Zalasky 1975; Sivanesan 1984).

Didymellaceae, Didymosphaeriaceae and Dothidotthiaceae

As has been mentioned before, Phoma sensu lato species have been proved to be highly polyphyletic, and they cluster in six distinct familial clades within the Pleosporales (Aveskamp et al. 2010). Most Phoma species, including the generic type (P. herbarum), clustered in Didymellaceae (Aveskamp et al. 2010). The clade of Didymellaceae also comprises other sections, such as Ampelomyces, Boeremia, Chaetasbolisia, Dactuliochaeta, Epicoccum, Peyronellaea, Phoma-like, Piggotia, Pithoascus, as well as the type species of Ascochyta and Microsphaeropsis (Aveskamp et al. 2010; de Gruyter et al. 2009; Kirk et al. 2008; Sivanesan 1984). Leptosphaerulina is another genus of Didymellaceae, which has hyphomycetous anamorphs with pigmented and muriform conidia, such as Pithomyces (Roux 1986).

The other reported anamorphs of Didymosphaeria are Fusicladiella-like, Dendrophoma, Phoma-like (Hyde et al. 2011). Hyphomycetous Thyrostroma links to Dothidotthiaceae (Phillips et al. 2008).

Some important plant pathogens are included within Didymellaceae, such as Phoma medicaginis Malbr. & Roum., which is a necrotrophic pathogen on Medicago truncatula (Ellwood et al. 2006). Phoma herbarum is another plant pathogen, which has potential as a biocontrol agent of weeds (Neumann and Boland 2002). Ascochyta rabiei is a devastating disease of chickpea in most of the chickpea producing countries (Saxena and Singh 1987).

Leptosphaeriaceae

The anamorphic stages of Leptosphaeriaceae can be Coniothyrium, Phoma, Plenodomus and Pyrenochaeta. All are coelomycetous anamorphs, and they may have phialidic or annellidic conidiogenous cells. Phoma heteromorphospora Aa & Kesteren, the type species of Phoma sect. Heterospora and Coniothyrium palmarum, the generic type of Coniothyrium, reside in Leptosphaeriaceae (de Gruyter et al. 2009).

Pleosporaceae

Various anamorphic types can occur in Pleosporaceae, which can be coelomycetous or hyphomycetous, and the ontogeny of conidiogenous cells can be phialidic, annellidic or sympodial blastic. Both Ascochyta caulina and Phoma betae belong to Pleosporaceae (de Gruyter et al. 2009).

Some species of Bipolaris and Curvularia are anamorphs of Cochliobolus. Many species of these two genera cause plant disease or even infect human beings (Khan et al. 2000). They are hyphomycetous anamorphs with sympodial proliferating conidiogenous cells, and pigmented phragmosporous poroconidia. The generic type of Lewia (L. scrophulariae) is linked with Alternaria conjuncta E.G. Simmons (Simmons 1986), and the generic type of Pleospora (P. herbarum) is linked with Stemphylium botryosum Sacc. (Sivanesan 1984). Both Alternaria and Stemphylium are hyphomycetous anamorphs characterized by pigmented, muriform conidia that develop at a very restricted site in the apex of distinctive conidiophores (Simmons 2007).

The generic type of Pleoseptum (P. yuccaesedum) is linked with Camarosporium yuccaesedum (Ramaley and Barr 1995), the generic type of Macrospora (M. scirpicola) with Nimbya scirpicola (Fuckel) E.G. Simmons (Simmons 1989), and the generic type of Setosphaeria (S. turcica) with Drechslera turcica (Pass.) Subram. & B.L. Jain (Sivanesan 1984). Pyrenophora has the anamorphic stages of Drechslera, and the anamorphic stage of Wettsteinina can be species of Stagonospora (Farr et al. 1989).

Most common anamorphs in Pleosporaceae are Alternaria, Bipolaris, Phoma-like and Stemphylium, and they can be saprobic or parasitic on various hosts. Phoma betae A.B. Frank is a notorious pathogen on sugar beet, which causes zonate leaf spot or Phomopsis of sugar beet. Alternaria porri (Ellis) Cif., Stemphylium solani G.F. Weber, S. botryosum and S. vesicarium (Wallr.) E.G. Simmons can cause leaf blight of garlic (Zheng et al. 2009). Phoma incompta Sacc. & Martelli is a pathogen on olive, and Stemphylium botryosum, the anamorph of Pleospora herbarum, causes leaf disease of olive trees (Malathrakis 1979).

Phaeosphaeriaceae

The type species of Phoma sect. Paraphoma (Phoma radicina (McAlpine) Boerema) as well as several pathogens on Gramineae, i.e. Stagonospora foliicola (Bres.) Bubák, S. neglecta var. colorata and Wojnowicia hirta Sacc. belong to Phaeosphaeriaceae (de Gruyter et al. 2009). Other anamorphs reported for Phaeosphaeriaceae are Amarenographium, Ampelomyces, Chaetosphaeronema, Coniothyrium, Hendersonia, Neosetophoma, ?Parahendersonia, Paraphoma, Phaeoseptoria, Rhabdospora, Scolecosporiella, Setophoma, Sphaerellopsis and Tiarospora.

These anamorphic fungi can be saprobic, but mostly pathogenic on herbaceous plants. For instance, Stagonospora foliicola and Coniothyrium concentricum (Desm.) Sacc. can cause leaf spots on herbaceous plants (Zeiders 1975), and Ampelomyces quisqualis Ces. is a hyperparasite of powdery mildews.

Pleosporales suborder Massarineae

Massarineae species are mostly saprobic in terrestrial or aquatic environments. Five families are currently included within Massarineae, viz. Lentitheciaceae, Massarinaceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae and Trematosphaeriaceae. Anamorphs of the five families are summarized as follows.

Lentitheciaceae

Stagonospora macropycnidia Cunnell nests within the clade of Lentitheciaceae (Plate 1). A relatively broad genus concept of Stagonospora is currently accepted, which comprises parasitic or saprobic taxa. Keissleriella cladophila (Niessl) Corbaz is another species nesting within Lentitheciaceae (Zhang et al. 2009a), and is linked with Dendrophoma sp., which has branching conidiogenous cells, and 1-celled, hyaline conidia (Bose 1961; Sivanesan 1984).

Massarinaceae

A relatively narrow concept tends to be accepted for Massarinaceae, which seems only to comprise limited species such as Byssothecium circinans, Massarina eburnea, M. cisti S.K. Bose, M. igniaria (C. Booth) Aptroot (anamorph: Periconia igniaria E.W. Mason & M.B. Ellis) and Neottiosporina paspali (G.F. Atk.) B. Sutton & Alcorn (Zhang et al. 2009a; Plate 1). Similarly, a relatively narrow generic concept of Massarina was accepted, containing only M. eburnea and M. cisti (Zhang et al. 2009b), and both species have been linked with species of Ceratophoma (Sivanesan 1984).

Montagnulaceae

Montagnula has an Aschersonia anamorph, and Kalmusia and Paraphaeosphaeria have Coniothyrium-like, Cytoplea, Microsphaeropsis and Paraconiothyrium anamorphs. The generic type of Paraphaeosphaeria (P. michotii) is linked with Coniothyrium scirpi Trail (Webster 1955). The Coniothyrium complex is highly polyphyletic, and was subdivided into four groups by Sutton (1980), viz. Coniothyrium, Microsphaeropsis, Cyclothyrium and Cytoplea. Paraconiothyrium was introduced to accommodate Coniothyrium minitans W.A. Campb. and C. sporulosum (W. Gams & Domsch) Aa, which are closely related to Paraphaeosphaeria based on 18S rDNA sequences phylogeny (Verkley et al. 2004).

Morosphaeriaceae

Based on the multigene phylogenetic analysis in this study, Asteromassaria is tentatively included in Morosphaeriaceae. Asteromassaria macrospora is linked with Scolicosporium macrosporium (Berk.) B. Sutton, which is hyphomycetous. No anamorphic stages have been reported for other species of Morosphaeriaceae.

Trematosphaeriaceae

Three species from three different genera were included in Trematosphaeriaceae, i.e. Falciformispora lignatilis, Halomassarina thalassiae and Trematosphaeria pertusa (Suetrong et al. data unpublished; Plate 1). Of these, only Trematosphaeria pertusa, the generic type of Trematosphaeria, produces hyphopodia-like structures on agar (Zhang et al. 2008a).

Other families of Pleosporales

Amniculicolaceae

Three anamorphic species nested within the clade of Amniculicolaceae, i.e. Anguillospora longissima (Sacc. & P. Syd.) Ingold, Repetophragma ontariense (Matsush.) W.P. Wu and Spirosphaera cupreorufescens Voglmayr (Zhang et al. 2009a). Sivanesan (1984, p. 500) described the teleomorphic stage of Anguillospora longissima as Massarina sp. II, which fits the diagnostic characters of Amniculicola well. Thus this taxon may be another species of Amniculicola.

Hypsostromataceae

A Pleurophomopsis-like anamorph is reported in the subiculum of the generic type of Hypsostroma (H. saxicola Huhndorf) (Huhndorf 1992).

Lophiostomataceae

The concept of Lophiostomataceae was also narrowed, and presently contains only Lophiostoma (Zhang et al. 2009a). Leuchtmann (1985) studied cultures of some Lophiostoma species, and noticed that L. caulium (Fr.) Ces. & De Not., L. macrostomum, L. semiliberum (Desm.) Ces. & De Not., Lophiostoma sp. and Lophiotrema nucula produced Pleurophomopsis anamorphic stages, which are similar to those now in Melanomma (Chesters 1938), but Lophiostoma and Melanomma has no proven phylogenetic relationship (Zhang et al. 2009a, b; Plate 1). Species of Aposphaeria have also been reported in Massariosphaeria (Farr et al. 1989; Leuchtmann 1984), but the polyphyletic nature of Massariosphaeria is well documented (Wang et al. 2007).

Melanommataceae

The anamorphs of the Melanommataceae are mostly coelomycetous and rarely hyphomycetous with various ontogenic structures, such as annellidic or sympodial for hyphomycetes (Exosporiella and Pseudospiropes) and coelomycetes (Aposphaeria-like and Pyrenochaeta).

Herpotrichia is reported as having a Pyrenochaeta anamorphic stage with or without seta on the surface of pycnidia (Sivanesan 1984). Aposphaeria and Phoma-like have been reported in Melanomma species (Chesters 1938; Sivanesan 1984). Similarly, the anamorphs of Karstenula are reported as coelomycetous, i.e. Microdiplodia (Constantinescu 1993). The anamorphic stage of Anomalemma is Exosporiella (Sivanesan 1983), and that of Byssosphaeria is Pyrenochaeta (Barr 1984). Ohleria brasiliensis Starbäck has been linked with Monodictys putredinis (Wallr.) S. Hughes (Samuels 1980). Astrosphaeriella is a contentious genus as its familial status is not determined yet. Here we temporarily assigned it under Melanommataceae, which is linked with the anamorph genus Pleurophomopsis.

Pleomassariaceae

Shearia and Prosthemium are all anamorphs of Pleomassaria, and Prosthemium betulinum is linked with the generic type of Pleomassaria (P. siparia) (Barr 1982b; Sivanesan 1984; Sutton 1980; Tanaka et al. 2010). Splanchnonema is a genus of Pleomassariaceae, the teleomorphic morphology of which is difficult to distinguish from two other genera, i.e. Asteromassaria and Pleomassaria, and the reported anamorphs of Splanchnonema are Ceuthodiplospora, Myxocyclus and Stegonsporium, which are comparable with those of Asteromassaria and Pleomassaria.

Tetraplosphaeriaceae

Tetraplosphaeriaceae was introduced to accommodate the Massarina-like bambusicolous fungi that produce Tetraploa sensu stricto anamorphs (Tanaka et al. 2009). Tetraploa aristata Berk. & Broome, the generic type of Tetraploa is widely distributed, associated with various substrates and many occur in freshwater or has been isolated from air. The polyphyletic nature of T. aristata has been well documented (Tanaka et al. 2009). Anamorphic stages can serve as a diagnostic character for this family.

Diademaceae, Massariaceae, Sporormiaceae and Teichosporaceae

The Sporormiaceae is coprophilous having Phoma or Phoma-related anamorphic states (Cannon and Kirk 2007). Comoclathris (Diademaceae) is linked with Alternaria-like anamorphs (Simmons 1952). Myxocyclus links to Massaria (Massariaceae) (Hyde et al. 2011). The anamorphic stage of Chaetomastia (Teichosporaceae) is Aposphaeria- or Coniothyrium-like (Barr 1989c).

Generally speaking, the morphologically simple conidiophores are usually considered phylogenetically uninformative (Seifert and Samuels 2000). Phoma-like anamorphs commonly occur in Pleosporales, while their colorless and unicellular conidia are also not phylogenetically informative (Seifert and Samuels 2000).

All of the above mentioned anamorphic taxa of Pleosporales have phialidic, annellidic or sympodial conidiogenous cells, representing apical wall-building type (compared to ring wall-building and diffused wall-building) (Nag Raj 1993), which may indicate that the wall-building type probably has phylogenetic significance.

Molecular phylogeny of Pleosporales

Numerous genes have been applied in phylogenetic studies of Pleosporales, mostly including LSU, SSU, mtSSU and ITS as well as the protein genes, such as RPB1, RPB2, TEF1, β-tubulin (TUB1) and actin (ACT1). A single gene such as ITS or LSU, has been used to study phylogenetic relationships between Leptosphaeria and Phaeosphaeria (Câmara et al. 2002) or Pleosporaceae and Tubeufiaceae (Kodsueb et al. 2006a, b) (Table 2). The use of these phylogenetic markers, although making important contributions, has not been successful in resolving numerous relationships in single gene dendrograms. One exception is the use of SSU sequences to demonstrate the phylogenetic significance of pseudoparaphyses (Liew et al. 2000) whilst rejecting the phylogenetic utility of pseudoparaphyses morphology (cellular or trabeculate). Analyses with combined genes have had more success. For instance combined analyses with LSU and SSU sequence data could be used to define family level classification in a few cases (Dong et al. 1998; de Gruyter et al. 2009; Lumbsch and Lindemuth 2001; Pinnoi et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2009b) (Table 2). The addition of more than two genes has been used to determine relationships between orders. For instance, genes such as LSU, SSU and mtSSU have been used to analyze ordinal relationships in Loculoascomycetes (Lindemuth et al. 2001), and to analyze phylogenetic relationships of coprophilous families in Pleosporales (Kruys et al. 2006). Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii (T. Rohde) Petr. was shown to belong in Dothideales based on LSU, SSU and ITS sequence analysis (Winton et al. 2007), while Schoch et al. (2006) used four genes, i.e. LSU, SSU, RPB2 and TEF1 to evaluate the phylogenetic relationships among different orders of the Dothideomycetes. Five genes, viz. LSU, SSU, TEF1, RPB1 and RPB2, were used to study the phylogenetic relationships of different orders within Dothideomycetes (Schoch et al. 2009) and of different families within Pleosporales (Zhang et al. 2009a) (Table 2). It is clear that even more genes will be required to address the remaining issues and the promise of genome analyses is within reach (www.jgi.doe.gov/sequencing/why/dothideomycetes.html) for Dothideomycetes.

Table 2.

List of phylogenetic studies in Pleosporales

| Year | Author(s) | Loci used | Target fungi | General conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Dong et al. | LSU, SSU | Leptosphaeriaceae, Pleosporaceae and three other families | Leptosphaeriaceae is paraphyletic and Pleosporaceae is monophyletic. |

| 2000 | Liew et al. | SSU | Pleosporales and Melanommatales | Pleosporales and Melanommatales are not naturial groups. |

| 2001 | Lindemuth et al. | LSU, SSU, mtSSU | loculoascomycetes | Loculoascomycetes are not monophyletic. |

| 2001 | Lumbsch and Lindemuth | LSU, SSU | Dothideomycetes | Presence of pseudoparaphyses is a major character at order level classification |

| 2002 | Câmara et al. | ITS | Leptosphaeria and Phaeosphaeria | Accepted Leptosphaeria sensu stricto. |

| 2006 | Kodsueb et al. | LSU | Pleosporaceae | Wettsteinina should be excluded from the Pleosporaceae. |

| 2006 | Kodsueb et al. | LSU | Tubeufiaceae | Tubeufiaceae is more closely related to the Venturiaceae. |

| 2006 | Kruys et al. | LSU, SSU, mtSSU | coprophilous familes of Pleosporales | coprophilous familes of Pleosporales form phylogenetic monophyletic groups, respectively |

| 2006 | Schoch et al. | LSU, SSU, TEF1, RPB2 | Dothideomycetes | Proposed the subclasses Pleosporomycetidae |

| 2007 | Pinnoi et al. | LSU, SSU | Pleosporales | phylogenetic relationships of different families of Pleosporales, introduced a new fungus–– Berkleasmium crunisia |

| 2007 | Wang et al. | LSU, SSU, RPB2 | Massariosphaeria | Massariosphaeria is not monophyletic |

| 2007 | Winton et al. | LSU, SSU, ITS | Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii | Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii located in Dothideales. |

| 2008a | Zhang et al. | LSU, SSU | Melanomma and Trematosphaeria | Melanomma and Trematosphaeria belong to different families |

| 2009 | de Gruyter et al. | LSU, SSU; | Phoma and related genera | They are closely related with Didymellaceae, Leptosphaeriaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae and Pleosporaceae |

| 2009a | Zhang et al. | LSU, SSU, TEF1, RPB1, RPB2 | Pleosporales | Amniculicolaceae and Lentitheciaceae were introduced, and Pleosporineae recircumscribed. |

| 2009 | Mugambi and Huhndorf | LSU, TEF1 | Melanommataceae, Lophiostomataceae | Recircumscribed Melanommataceae and Lophiostomataceae, and reinstated Hypsostromataceae. |

| 2009 | Nelsen et al. | LSU and mtSSU | lichenized Dothideomycetes | Pyrenocarpous lichens with bitunicate asci are not monophyletic, but belong to at least two classes (Dothideomycetes and Erotiomycetes). |

| 2009 | Suetrong et al. | LSU, SSU, TEF1, RPB1 | marine Dothideomycetes | Two new families are introduced Aigialaceae and Morosphaeriaceae. |

| 2009 | Shearer et al. | LSU, SSU | freshwater Dothideomycetes | Freshwater Dothideomycetes are related to terrestrial taxa and have adapted to freshwater habitats numerous times. |

| 2009 | Tanaka et al. | LSU, SSU, TEF1, ITS, BT | bambusicolous Pleosporales | Introduced Tetraplosphaeriaceae with Tetraploa-like anamorphs. |

| 2009 | Kruys and Wedin | ITS-nLSU, mtSSU rDNA and β-tubulin | Sporormiaceae | Analyzed the inter-generic relationships as well as evaluated the morphological significance used in this family. |

| 2010 | Hirayama et al. | LSU, SSU | Massarina ingoldiana sensu lato | Massarina ingoldiana sensu lato is polyphyletic, and separated into two clades within Pleosporales. |

| 2010 | Aveskamp et al. | LSU, SSU, ITS and β-tubulin | Phoma and related genera within Didymellaceae | Rejected current Boeremaean subdivision. |

| 2010 | de Gruyter et al. | LSU, SSU | Phoma and related genera within Pleosporineae | Introduced Pyrenochaetopsis, Setophoma and Neosetophoma and reinstated Cucurbitariaceae within Pleosporineae |

The importance of generic type specimens

The type specimen (collection type) is a fundamental element in the current Code of Botanical Nomenclature at familial or lower ranks (Moore 1998). A type specimen fixes the name to an exact specimen at family, genera, species and variety/subspecies rank and is ultimately based on this single specimen, i.e. a family name is based on a genus, the genus name is based on a species, and the species name is based on a specimen (Kirk et al. 2008).

The generic type is of great importance in defining generic circumscriptions in fungal taxonomy. The generic types of Pleosporales have been studied previously by many mycologists. For instance, Müller and von Arx (1962) studied the generic types of “Pyrenomycetes”, and described and illustrated them in detail. Sivanesan (1984) described and illustrated the generic representatives of Loculoascomycetes for both their teleomorphs and anamorphs, and their links were emphasized. A large number of pleosporalean genera have been studied by Barr (1990a, b). Almost all of the previous work was conducted more than 20 years ago, when no molecular phylogenetic studies could be carried out and thus had been carried out in a systematic fashion.

Aim and outline of present study

The present study had two principal objectives:

To explore genera under Pleosporales based on the generic types and provide a detailed description and illustration for the type species of selected genera, discuss the study history of those genera, and explore their ordinal, familial, and generic relationships;

To investigate the phylogeny of Pleosporales, its inter-familial relationships, and the morphological circumscription of each family;

In order to clarify morphological characters, the generic types of the majority of teleomorphic pleosporalean genera (> 60%) were studied. Most of them are from the “core families” of Pleosporales, i.e. Delitschiaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Massariaceae, Massarinaceae, Melanommataceae, Montagnulaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae, Phaeotrichaceae, Pleomassariaceae, Pleosporaceae, Sporormiaceae and Teichosporaceae. Notes are given for those where type specimens could not be obtained during the timeframe of this study. A detailed description and illustration of each generic type is provided. Comments, notes and problems that need to be addressed are provided for each genus. Phylogenetic investigation based on five nuclear loci, viz. LSU, SSU, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF1 was carried out using available strains from numerous genera in Pleosporales. In total, 278 pleosporalean taxa are included in the phylogenetic analysis, which form 25 familial clades on the dendrogram (Plate 1). The suborder, Massarineae, is emended to accommodate Lentitheciaceae, Massarinaceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae and Trematosphaeriaceae.

Materials and methods

Molecular phylogeny

Four genes were used in this analysis, the large and small subunits of the nuclear ribosomal RNA genes (LSU, SSU) and two protein coding genes, namely the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) and translation elongation factor-1 alpha (TEF1). All sequences were downloaded from GenBank as listed in Table 3. Each of the individual ribosomal genes was aligned in SATé under default settings with at least 20 iterations. The protein coding genes were aligned in BioEdit (Hall 2004) and completed by manual adjustment. Introns were removed and all genes were concatenated in a single nucleotide alignment with 43% missing and gap characters out of a total set of 5081. The alignment had 100% representation for LSU, 75% for SSU, 48% for RPB2 and 65% for TEF1. The final data matrix had 280 taxa including outgroups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Taxa used in the phylogenetic analysis and their corresponding GenBank numbers. Culture and voucher abbreviations are indicated were available

| Species | Culture/voucher1 | LSU | SSU | RPB2 | TEF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrocordiopsis patilii | BCC 28166 | GU479772 | GU479736 | GU479811 | |

| Acrocordiopsis patilii | BCC 28167 | GU479773 | GU479737 | GU479812 | |

| Aigialus grandis | BCC 18419 | GU479774 | GU479738 | GU479813 | GU479838 |

| Aigialus grandis | JK 5244A | GU301793 | GU296131 | GU371762 | |

| Aigialus mangrovis | BCC 33563 | GU479776 | GU479741 | GU479815 | GU479840 |

| Aigialus mangrovis | BCC 33564 | GU479777 | GU479742 | GU479816 | GU479841 |

| Aigialus parvus | A6 | GU301795 | GU296133 | GU371771 | GU349064 |

| Aigialus parvus | BCC 32558 | GU479779 | GU479743 | GU479818 | GU479843 |

| Aigialus rhizophorae | BCC 33572 | GU479780 | GU479745 | GU479819 | GU479844 |

| Aigialus rhizophorae | BCC 33573 | GU479781 | GU479746 | GU479820 | GU479845 |

| Alternaria alternata | CBS 916.96 | DQ678082 | DQ678031 | DQ677980 | DQ677927 |

| Amniculicola immersa | CBS 123083 | FJ795498 | GU456295 | GU456358 | GU456273 |

| Amniculicola parva | CBS 123092 | FJ795497 | GU296134 | GU349065 | |

| Anteaglonium abbreviatum | ANM 925.1 | GQ221877 | GQ221924 | ||

| Anteaglonium abbreviatum | GKM 1029 | GQ221878 | GQ221915 | ||

| Anteaglonium globosum | ANM 925.2 | GQ221879 | GQ221925 | ||

| Anteaglonium latirostrum | L100N 2 | GQ221876 | GQ221938 | ||

| Arthopyrenia salicis | 1994 Coppins | AY607730 | |||

| Arthopyrenia salicis | CBS 368.94 | AY538339 | AY538333 | ||

| Ascochyta pisi | CBS 126.54 | DQ678070 | DQ678018 | DQ677967 | DQ677913 |

| Ascocratera manglicola | BCC 09270 | GU479782 | GU479747 | GU479821 | GU479846 |

| Ascocratera manglicola | JK 5262 C | GU301799 | GU296136 | GU371763 | |

| Asteromassaria pulchra | CBS 124082 | GU301800 | GU296137 | GU371772 | GU349066 |

| Astrosphaeriella aggregata | MAFF 239485 | AB524590 | AB524449 | ||

| Astrosphaeriella aggregata | MAFF 239486 | AB524591 | AB524450 | AB539105 | AB539092 |

| Astrosphaeriella bakeriana | CBS 115556 | GU301801 | GU349015 | ||

| Astrosphaeriella stellata | MAFF 239487 | AB524592 | AB524451 | ||

| Beverwykella pulmonaria | CBS 283.53 | GU301804 | GU371768 | ||

| Biatriospora marina | CY 1228 | GQ925848 | GQ925835 | GU479823 | GU479848 |

| Bimuria novae-zelandiae | CBS 107.79 | AY016356 | AY016338 | DQ470917 | DQ471087 |

| Byssolophis sphaerioides | IFRDCC2053 | GU301805 | GU296140 | GU456348 | GU456263 |

| Byssosphaeria jamaicana | SMH1403 | GU385152 | GU327746 | ||

| Byssosphaeria rhodomphala | GKM L153N | GU385157 | GU327747 | ||

| Byssosphaeria salebrosa | SMH2387 | GU385162 | GU327748 | ||

| Byssosphaeria schiedermayeriana | GKM1197 | GU385161 | GU327750 | ||

| Byssosphaeria schiedermayeriana | GKM152N | GU385168 | GU327749 | ||

| Byssosphaeria villosa | GKM204N | GU385151 | GU327751 | ||

| Byssothecium circinans | CBS 675.92 | AY016357 | AY016339 | DQ767646 | GU349061 |

| Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum | CBS 216.75 | EU754144 | EU754045 | GU371777 | |

| Cochliobolus heterostrophus | CBS 134.39 | AY544645 | AY544727 | DQ247790 | DQ497603 |

| Cochliobolus sativus | DAOM 226212 | DQ678045 | DQ677995 | DQ677939 | |

| Corynespora cassiicola | CBS 100822 | GU301808 | GU296144 | GU371742 | GU349052 |

| Corynespora olivacea | CBS 114450 | GU301809 | GU349014 | ||

| Corynespora smithii | CABI 5649b | GU323201 | GU371783 | GU349018 | |

| Cucurbitaria berberidis | CBS 394.84 | GQ387605 | GQ387544 | ||

| Decaisnella formosa | BCC 25616 | GQ925846 | GQ925833 | GU479825 | GU479851 |

| Decaisnella formosa | BCC 25617 | GQ925847 | GQ925834 | GU479824 | GU479850 |

| Decorospora gaudefroyi | CBS 332.63 | EF177849 | AF394542 | ||

| Delitschia cf. chaetomioides | GKM 1283 | GU385172 | |||

| Delitschia cf. chaetomioides | GKM 3253.2 | GU390656 | |||

| Delitschia chaetomioides | GKM1283 | GU385172 | GU327752 | ||

| Delitschia chaetomioides | SMH3253.2 | GU390656 | GU327753 | ||

| Delitschia winteri | CBS 225.62 | DQ678077 | DQ678026 | DQ677975 | DQ677922 |

| Didymella exigua | CBS 183.55 | EU754155 | EU754056 | ||

| Didymocrea sadasivanii | CBS 438 65 | DQ384103 | DQ384066 | ||

| Didymosphaeria futilis | CMW 22186 | EU552123 | |||

| Didymosphaeria futilis | HKUCC 5834 | GU205219 | GU205236 | ||

| Dothidotthia aspera | CPC 12933 | EU673276 | EU673228 | ||

| Dothidotthia symphoricarpi | CBS119687 | EU673273 | EU673224 | ||

| Entodesmium rude | CBS 650.86 | GU301812 | GU349012 | ||

| Falciformispora lignatilis | BCC 21117 | GU371826 | GU371834 | GU371819 | |

| Falciformispora lignatilis | BCC 21118 | GU371827 | GU371835 | GU371820 | |

| Floricola striata | JK 5603 K | GU479785 | GU479751 | ||

| Floricola striata | JK 5678I | GU301813 | GU296149 | GU371758 | |

| Halomassarina thalassiae | BCC 17055 | GQ925850 | GQ925843 | ||

| Halomassarina thalassiae | JK 5262D | GU301816 | GU349011 | ||

| Halotthia posidoniae | BBH 22481 | GU479786 | GU479752 | ||

| Helicascus nypae | BCC 36751 | GU479788 | GU479754 | GU479826 | GU479854 |

| Helicascus nypae | BCC 36752 | GU479789 | GU479755 | GU479827 | GU479855 |

| Herpotrichia diffusa | CBS 250.62 | DQ678071 | DQ678019 | DQ677968 | DQ677915 |

| Herpotrichia juniperi | CBS 200.31 | DQ678080 | DQ678029 | DQ677978 | DQ677925 |

| Herpotrichia macrotricha | GKM196N | GU385176 | GU327755 | ||

| Herpotrichia macrotricha | SMH269 | GU385177 | GU327756 | ||

| Hypsostroma caimitalense | GKM 1165 | GU385180 | |||

| Hypsostroma saxicola | SMH 5005 | GU385181 | |||

| Hysterium angustatum | CBS 123334 | FJ161207 | FJ161167 | FJ161129 | FJ161111 |

| Hysterium angustatum | CBS 236.34 | FJ161180 | GU397359 | FJ161117 | FJ161096 |

| Julella avicenniae | BCC 18422 | GU371823 | GU371831 | GU371787 | GU371816 |

| Julella avicenniae | BCC 20173 | GU371822 | GU371830 | GU371786 | GU371815 |

| Julella avicenniae | JK 5326A | GU479790 | GU479756 | ||

| Kalmusia scabrispora | MAFF 239517 | AB524593 | AB524452 | AB539093 | AB539106 |

| Kalmusia scabrispora | NBRC 106237 | AB524594 | AB524453 | AB539094 | AB539107 |

| Karstenula rhodostoma | CBS 690.94 | GU301821 | GU296154 | GU371788 | GU349067 |

| Katumotoa bambusicola | MAFF 239641 | AB524595 | AB524454 | AB539095 | AB539108 |

| Keissleriella cladophila | CBS 104.55 | GU301822 | GU296155 | GU371735 | GU349043 |

| Keissleriella rara | CBS 118429 | GU479791 | GU479757 | ||

| Kirschsteiniothelia elaterascus | A22-5A/HKUCC7769 | AY787934 | AF053727 | ||

| Lentithecium aquaticum | CBS 123099 | GU301823 | GU296156 | GU371789 | GU349068 |

| Lentithecium arundinaceum | CBS 123131 | GU456320 | GU456298 | GU456281 | |

| Lentithecium arundinaceum | CBS 619.86 | GU301824 | GU296157 | FJ795473 | |

| Lentithecium fluviatile | CBS 122367 | GU301825 | GU296158 | GU349074 | |

| Lepidosphaeria nicotiae | CBS 101341 | DQ678067 | DQ677963 | DQ677910 | |

| Leptosphaeria biglobosa | CBS 298.36 | GU237980 | GU238207 | ||

| Leptosphaeria biglobosa | CBS 303.51 | GU301826 | GU349010 | ||

| Leptosphaeria doliolum | CBS 505.75 | GU301827 | GU296159 | GU349069 | |

| Leptosphaeria dryadis | CBS 643.86 | GU301828 | GU371733 | GU349009 | |

| Leptosphaerulina argentinensis | CBS 569.94 | GU301829 | GU349008 | ||

| Leptosphaerulina australis | CBS 311.51-T | FJ795500 | GU456357 | GU456272 | |

| Leptosphaerulina australis | CBS 317.83 | GU301830 | GU296160 | GU371790 | GU349070 |

| Leptosphearia maculans | DAOM 229267 | DQ470946 | DQ470993 | DQ470894 | DQ471062 |

| Letendraea helminthicola | CBS 884.85 | AY016362 | AY016345 | ||

| Letendraea padouk | CBS 485.70 | AY849951 | GU296162 | ||

| Lindgomyces breviappendiculatus | KT 1399 | AB521749 | AB521734 | ||

| Lindgomyces cinctosporae | R56-1 | AB522431 | AB522430 | ||

| Lindgomyces cinctosporae | R56-3 | GU266245 | GU266238 | ||

| Lindgomyces ingoldianus | KH 100 JCM 16479 | AB521737 | AB521720 | ||

| Lindgomyces rotundatus | KH 114 JCM 16484 | AB521742 | AB521725 | ||

| Lophiostoma alpigenum | GKM 1091b | GU385193 | |||

| Lophiostoma arundinis | CBS 621.86 | DQ782384 | DQ782383 | DQ782386 | DQ782387 |

| Lophiostoma caulium | CBS 623.86 | GU301833 | GU296163 | GU371791 | |

| Lophiostoma compressum | IFRD 2014 | GU301834 | GU296164 | FJ795457 | |

| Lophiostoma crenatum | CBS 629.86 | DQ678069 | DQ678017 | DQ677965 | DQ677912 |

| Lophiostoma fuckelii | CBS 101952 | DQ399531 | |||

| Lophiostoma fuckelii | CBS 113432 | EU552139 | |||

| Lophiostoma fuckelii | GKM 1063 | GU385192 | |||

| Lophiostoma macrostomum | CBS 122681 | EU552141 | |||

| Lophiostoma macrostomum | HHUF 27293 | AB433274 | |||

| Lophiostoma macrostomum | KT 635 | AB433273 | AB521731 | ||

| Lophiostoma quadrinucleatum | GKM1233 | GU385184 | GU327760 | ||

| Lophiostoma sagittiforme | HHUF 29754 | AB369267 | |||

| Lophiotrema brunneosporum | CBS 123095 | GU301835 | GU296165 | GU349071 | |

| Lophiotrema lignicola | CBS 122364 | GU301836 | GU296166 | GU349072 | |

| Massarina arundinariae | MAFF 239461 | AB524596 | AB524455 | AB539096 | AB524817 |

| Massarina arundinariae | NBRC 106238 | AB524597 | AB524456 | AB539097 | AB524818 |

| Lophiotrema nucula | CBS 627.86 | GU301837 | GU296167 | GU371792 | GU349073 |

| Loratospora aestuarii | JK 5535B | GU301838 | GU296168 | GU371760 | |

| Macroventuria anomochaeta | CBS 525.71 | GU456315 | GU456346 | GU456262 | |

| Massaria anomia | CBS 123109 | GU301792 | GU296130 | GU349062 | |

| Massaria anomia | CBS 591.78 | GU301839 | GU296169 | GU371769 | |

| Massaria ariae | M52 | HQ599382 | HQ599456 | HQ599322 | |

| Massaria aucupariae | M49 | HQ599384 | HQ599455 | HQ599324 | |

| Massaria campestris | M28 | HQ599385 | HQ599449 | HQ599459 | HQ599325 |

| Massaria conspurcata | M14 | HQ599393 | HQ599441 | HQ599333 | |

| Massaria gigantispora | M26 | HQ599397 | HQ599447 | HQ599337 | |

| Massaria inquinans | M19 | HQ599402 | HQ599444 | HQ599460 | HQ599342 |

| Massaria lantanae | M18 | HQ599406 | HQ599443 | HQ599346 | |

| Massaria macra | M3 | HQ599408 | HQ599450 | HQ599348 | |

| Massaria mediterranea | M45 | HQ599417 | HQ599452 | HQ599357 | |

| Massaria platanoidea | M7 | HQ599420 | HQ599457 | HQ599462 | HQ599359 |

| Massaria pyri | M21 | HQ599424 | HQ599445 | HQ599363 | |

| Massaria vindobonensis | M27 | HQ599429 | HQ599448 | HQ599464 | HQ599368 |

| Massaria vomitoria | M13 | HQ599437 | HQ599440 | HQ599466 | HQ599375 |

| Massarina cisti | CBS 266.62 | FJ795447 | FJ795490 | FJ795464 | |

| Massarina eburnea | CBS 473.64 | GU301840 | GU296170 | GU371732 | GU349040 |

| Massarina igniaria | CBS 845.96 | GU301841 | GU296171 | GU371793 | |

| Massarina ricifera | JK 5535 F | GU479793 | GU479759 | ||

| Massariosphaeria phaeospora | CBS 611.86 | GU301843 | GU296173 | GU371794 | |

| Mauritiana rhizophorae | BCC 28866 | GU371824 | GU371832 | GU371796 | GU371817 |

| Mauritiana rhizophorae | BCC 28867 | GU371825 | GU371833 | GU371797 | GU371818 |

| Melanomma pulvis-pyrius | CBS 124080 | GU456323 | GU456302 | GU456350 | GU456265 |

| Melanomma pulvis-pyrius | CBS 371.75 | GU301845 | GU371798 | GU349019 | |

| Melanomma pulvis-pyrius | SMH 3291 | GU385197 | |||

| Melanomma rhododendri | ANM 73 | GU385198 | |||

| Misturatosphaeria aurantonotata | GKM1238 | GU385173 | GU327761 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria aurantonotata | GKM1280 | GU385174 | GU327762 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria claviformis | GKM1210 | GU385212 | GU327763 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria kenyensis | GKM1195 | GU385194 | GU327767 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria kenyensis | GKM L100Na | GU385189 | GU327766 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria minima | GKM169N | GU385165 | GU327768 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria tennesseensis | ANM911 | GU385207 | GU327769 | ||

| Misturatosphaeria uniseptata | SMH4330 | GU385167 | GU327770 | ||

| Monascostroma innumerosum | CBS 345.50 | GU301850 | GU296179 | GU349033 | |

| Monotosporella tuberculata | CBS 256.84 | GU301851 | GU349006 | ||

| Montagnula anthostomoides | CBS 615.86 | GU205223 | GU205246 | ||

| Montagnula opulenta | CBS 168.34 | DQ678086 | AF164370 | DQ677984 | |

| Morosphaeria ramunculicola | BCC 18405 | GQ925854 | GQ925839 | ||

| Morosphaeria ramunculicola | JK 5304B | GU479794 | GU479760 | GU479831 | |

| Morosphaeria velataspora | BCC 17059 | GQ925852 | GQ925841 | ||

| Morosphaeria velataspora | BCC 17058 | GQ925851 | GQ925840 | ||

| Massariosphaeria grandispora | CBS 613 86 | GU301842 | GU296172 | GU371725 | GU349036 |

| Massariosphaeria typhicola | CBS 123126 | GU301844 | GU296174 | GU371795 | |

| Neophaeosphaeria filamentosa | CBS 102202 | GQ387577 | GQ387516 | GU371773 | GU349084 |

| Neotestudina rosatii | CBS 690.82 | DQ384069 | |||

| Neottiosporina paspali | CBS 331.37 | EU754172 | EU754073 | GU371779 | GU349079 |

| Ophiosphaerella herpotricha | CBS 240.31 | DQ767656 | DQ767650 | DQ767645 | DQ767639 |

| Ophiosphaerella herpotricha | CBS 620.86 | DQ678062 | DQ678010 | DQ677958 | DQ677905 |

| Ophiosphaerella sasicola | MAFF 239644 | AB524599 | AB524458 | AB539098 | AB539111 |

| Paraconiothyrium minitans | CBS 122788 | EU754173 | EU754074 | GU371776 | GU349083 |

| Paraphaeosphaeria michotii | CBS 591.73 | GU456326 | GU456305 | GU456352 | GU456267 |

| Paraphaeosphaeria michotii | CBS 652.86 | GU456325 | GU456304 | GU456351 | GU456266 |

| Phaeosphaeria ammophilae | CBS 114595 | GU301859 | GU296185 | GU371724 | GU349035 |

| Phaeosphaeria avenaria | CBS 602.86 | AY544684 | AY544725 | DQ677941 | DQ677885 |

| Phaeosphaeria avenaria | DAOM 226215 | AY544684 | AY544725 | DQ677941 | DQ677885 |

| Phaeosphaeria brevispora | MAFF 239276 | AB524600 | AB524459 | AB539099 | AB539112 |

| Phaeosphaeria brevispora | NBRC 106240 | AB524601 | AB524460 | AB539100 | AB539113 |

| Phaeosphaeria caricis | CBS 120249 | GU301860 | GU349005 | ||

| Phaeosphaeria elongata | CBS 120250 | GU456327 | GU456306 | GU456345 | GU456261 |

| Phaeosphaeria eustoma | CBS 573.86 | DQ678063 | DQ678011 | DQ677959 | DQ677906 |

| Phaeosphaeria luctuosa | CBS 308.79 | GU301861 | GU349004 | ||

| Phaeosphaeria nigrans | CBS 576.86 | GU456331 | GU456356 | GU456271 | |

| Phaeosphaeria nodorum | CBS 259.49 | GU456332 | GU456285 | ||

| Phaeosphaeria oryzae | CBS 110110 | GQ387591 | GQ387530 | ||

| Phaeosphaeriopsis musae | CBS 120026 | GU301862 | GU296186 | GU349037 | |

| Phoma apiicola | CBS 285.72 | GU238040 | GU238211 | ||

| Phoma betae | CBS 109410 | EU754178 | EU754079 | GU371774 | GU349075 |

| Phoma complanata | CBS 268.92 | EU754180 | EU754081 | GU371778 | GU349078 |

| Phoma cucurbitacearum | CBS 133.96 | GU301863 | GU371767 | ||

| Phoma exigua | CBS 431.74 | EU754183 | EU754084 | GU371780 | GU349080 |

| Phoma glomerata | CBS 528.66 | EU754184 | EU754085 | GU371781 | GU349081 |

| Phoma herbarum | CBS 276.37 | DQ678066 | DQ678014 | DQ677962 | DQ677909 |

| Phoma radicina | CBS 111.79 | EU754191 | EU754092 | GU349076 | |

| Phoma valerianae | CBS 630.68 | GU238150 | GU238229 | ||

| Phoma vasinfecta | CBS 539.63 | GU238151 | GU238230 | ||

| Phoma violicola | CBS 306.68 | GU238156 | GU238231 | ||

| Phoma zeae-maydis | CBS 588.69 | EU754192 | EU754093 | GU371782 | GU349082 |

| Platychora ulmi | CBS 361.52 | EF114702 | EF114726 | ||

| Lophiostoma compressum | GKM1048 | GU385204 | GU327772 | ||

| Lophiostoma scabridisporum | BCC 22836 | GQ925845 | GQ925832 | GU479829 | GU479856 |

| Lophiostoma scabridisporum | BCC 22835 | GQ925844 | GQ925831 | GU479830 | GU479857 |

| Pleomassaria siparia | CBS 279.74 | DQ678078 | DQ678027 | DQ677976 | DQ677923 |

| Pleospora ambigua | CBS 113979 | AY787937 | |||

| Pleospora herbarum | CBS 191.86 | DQ247804 | DQ247812 | DQ247794 | DQ471090 |

| Polyplosphaeria fusca | CBS 125425 | AB524607 | AB524466 | AB524822 | |

| Polyplosphaeria fusca | MAFF 239687 | AB524606 | AB524465 | ||

| Preussia funiculata | CBS 659.74 | GU301864 | GU296187 | GU371799 | GU349032 |

| Preussia lignicola | CBS 264.69 | GU301872 | GU296197 | GU371765 | GU349027 |

| Preussia terricola | DAOM 230091 | AY544686 | AY544726 | DQ470895 | DQ471063 |

| Prosthemium betulinum | CBS 127468 | AB553754 | AB553644 | ||

| Prosthemium canba | JCM 16966 | AB553760 | AB553646 | ||

| Prosthemium orientale | JCM 12841 | AB553748 | AB553641 | ||

| Prosthemium stellare | CBS 126964 | AB553781 | AB553650 | ||

| Pseudotetraploa curviappendiculata | CBS 125426 | AB524610 | AB524469 | AB524825 | |

| Pseudotetraploa curviappendiculata | MAFF 239495 | AB524608 | AB524467 | ||

| Pseudotetraploa javanica | MAFF 239498 | AB524611 | AB524470 | AB524826 | |

| Pseudotetraploa longissima | MAFF 239497 | AB524612 | AB524471 | AB524827 | |

| Pseudotrichia guatopoensis | SMH4535 | GU385202 | GU327774 | ||

| Pyrenochaeta acicola | CBS 812.95 | GQ387602 | GQ387541 | ||

| Pleurophoma cava | CBS 257.68 | EU754199 | EU754100 | ||

| Pyrenochaeta corn | CBS 248.79 | GQ387608 | GQ387547 | ||

| Pyrenochaeta nobilis | CBS 292.74 | GQ387615 | GQ387554 | ||

| Pyrenochaeta nobilis | CBS 407.76 | DQ678096 | DQ677991 | DQ677936 | |

| Pyrenochaeta quercina | CBS 115095 | GQ387619 | GQ387558 | ||

| Pyrenochaeta unguis-hominis | CBS 378.92 | GQ387621 | GQ387560 | ||

| Pyrenochaetopsis decipiens | CBS 343.85 | GQ387624 | GQ387563 | ||

| Pyrenophora phaeocomes | DAOM 222769 | DQ499596 | DQ499595 | DQ497614 | DQ497607 |

| Pyrenophora tritici-repentis | OSC 100066 | AY544672 | DQ677882 | ||

| Quadricrura bicornis | CBS 125427 | AB524613 | AB524472 | AB524828 | |

| Quadricrura meridionalis | CBS 125684 | AB524614 | AB524473 | AB524829 | |

| Quadricrura septentrionalis | CBS 125428 | AB524617 | AB524476 | AB524832 | |

| Quintaria lignatilis | BCC 17444 | GU479797 | GU479764 | GU479832 | GU479859 |

| Quintaria lignatilis | CBS 117700 | GU301865 | GU296188 | GU371761 | |

| Quintaria submersa | CBS 115553 | GU301866 | GU349003 | ||

| Repetophragma ontariense | HKUCC 10830 | DQ408575 | DQ435077 | ||

| Rimora mangrovei | JK 5246A | GU301868 | GU296193 | GU371759 | |

| Rimora mangrovei | JK 5437B | GU479798 | GU479765 | ||

| Roussoella hysterioides | CBS 125434 | AB524622 | AB524481 | AB539102 | AB539115 |

| Roussoella hysterioides | MAFF 239636 | AB524621 | AB524480 | AB539101 | AB539114 |

| Roussoella pustulans | MAFF 239637 | AB524623 | AB524482 | AB539103 | AB539116 |

| Roussoellopsis tosaensis | MAFF 239638 | AB524625 | AB539104 | AB539117 | |

| Saccothecium sepincola | CBS 278.32 | GU301870 | GU296195 | GU371745 | GU349029 |

| Salsuginea ramicola | KT 2597.1 | GU479800 | GU479767 | GU479833 | GU479861 |

| Salsuginea ramicola | KT 2597.2 | GU479801 | GU479768 | GU479834 | GU479862 |

| Setomelanomma holmii | CBS 110217 | GU301871 | GU296196 | GU371800 | GU349028 |

| Setosphaeria monoceras | AY016368 | AY016368 | |||

| Massaria platani | CBS 221.37 | DQ678065 | DQ678013 | DQ677961 | DQ677908 |

| Sporormiella minima | CBS 524.50 | DQ678056 | DQ678003 | DQ677950 | DQ677897 |

| Stagonospora macropycnidia | CBS 114202 | GU301873 | GU296198 | GU349026 | |

| Tetraploa aristata | CBS 996.70 | AB524627 | AB524486 | AB524836 | |

| Tetraplosphaeria nagasakiensis | MAFF 239678 | AB524630 | AB524489 | AB524837 | |

| Lophiostoma macrostomoides | GKM1033 | GU385190 | GU327776 | ||

| Lophiostoma macrostomoides | GKM1159 | GU385185 | GU327778 | ||

| Thyridaria rubronotata | CBS 419.85 | GU301875 | GU371728 | GU349002 | |

| Tingoldiago graminicola | KH 68 | AB521743 | AB521726 | ||

| Trematosphaeria pertusa | CBS 122368 | FJ201990 | FJ201991 | FJ795476 | GU456276 |

| Trematosphaeria pertusa | CBS 122371 | GU301876 | GU348999 | GU371801 | GU349085 |

| Trematosphaeria pertusa | SMH 1448 | GU385213 | |||

| Triplosphaeria cylindrica | MAFF 239679 | AB524634 | AB524493 | ||

| Triplosphaeria maxima | MAFF 239682 | AB524637 | AB524496 | ||

| Triplosphaeria yezoensis | CBS 125436 | AB524638 | AB524497 | AB524844 | |

| Ulospora bilgramii | CBS 110020 | DQ678076 | DQ678025 | DQ677974 | DQ677921 |

| Verruculina enalia | BCC 18401 | GU479802 | GU479770 | GU479835 | GU479863 |

| Verruculina enalia | BCC 18402 | GU479803 | GU479771 | GU479836 | GU479864 |

| Westerdykella cylindrica | CBS 454.72 | AY004343 | AY016355 | DQ470925 | DQ497610 |

| Westerdykella dispersa | CBS 508.75 | DQ468050 | U42488 | ||

| Westerdykella ornata | CBS 379.55 | GU301880 | GU296208 | GU371803 | GU349021 |

| Wicklowia aquatica | AF289-1 | GU045446 | |||

| Wicklowia aquatica | CBS 125634 | GU045445 | GU266232 | ||

| Xenolophium applanatum | CBS 123123 | GU456329 | GU456312 | GU456354 | GU456269 |

| Xenolophium applanatum | CBS 123127 | GU456330 | GU456313 | GU456355 | GU456270 |

| Zopfia rhizophila | CBS 207.26 | DQ384104 | L76622 |

1 BCC Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms; CABI International Mycological Institute, CABI-Bioscience, Egham, Bakeham Lane, U.K.; CBS Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; DAOM Plant Research Institute, Department of Agriculture (Mycology), Ottawa, Canada; DUKE Duke University Herbarium, Durham, North Carolina, U.S.A.; HHUF Herbarium of Hirosaki University, Japan; IFRDCC Culture Collection, International Fungal Research & Development Centre, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Kunming, China; MAFF Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan; NBRC NITE Biological Resource Centre, Japan; OSC Oregon State University Herbarium, U.S.A.; UAMH University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; UME Herbarium of the University of Umeå, Umeå, Sweden; Culture and specimen abbreviations: ANM A.N. Miller; CPC; P.W. Crous; EB E.W.A. Boehm; EG E.B.G. Jones; GKM G.K. Mugambi; JK J. Kohlmeyer; KT K. Tanaka; SMH S.M. Huhndorf

Previous results indicated no clear conflict amongst the majority of the data used (Schoch et al. 2009). A phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated alignment was performed on CIPRES webportal (Miller et al. 2009) using RAxML v. 7.2.7 (Stamatakis 2006; Stamatakis et al. 2008) applying unique model parameters for each gene and codon (8 partitions). A general time reversible model (GTR) was applied with a discrete gamma distribution and four rate classes. Fifty thorough maximum likelihood (ML) tree searches were done in RAxML v. 7.2.7 under the same model, each one starting from a separate randomized tree and the best scoring tree selected with a final likelihood value of −95238.628839. Two isolates of Hysterium angustatum (Hysteriales, Pleosporomycetidae) were used as outgroups based on earlier work (Boehm et al. 2009a). Bootstrap pseudo-replicates were run with the GTRCAT model approximation, allowing the program to halt bootstraps automatically under the majority rule criterion (Pattengale et al. 2010). The resulting 250 replicates were plotted on to the best scoring tree obtained previously. The phylogram with bootstrap values on the branches is presented in Plate 1 by using graphical options available in TreeDyn v. 198.3 (Chevenet et al. 2006).

Morphology

Type specimens as well as some other specimens were loaned from the following herbaria: BAFC, BISH, BPI, BR, BRIP, CBS, E, ETH, FFE, FH, G, H, Herb. J. Kohlmeyer, HHUF, IFRD, ILLS, IMI, K(M), L, LPS, M, MA, NY, PAD, PC, PH, RO, S, TNS, TRTC, UB, UBC, UPS and ZT. Attempts were made to trace and borrow all the type specimens from herbaria worldwide, but only some of them could be obtained. Some of the type specimens are in such bad condition that little information could be obtained. In order to obtain the location of specimens, original publications were searched.

Ascostroma and ascomata were examined under an Olympus SZ H10 dissecting microscope. Section of the fruiting structures was carried out by cryotome or by hand-cutting. Measurements and descriptions of sections of the ascomata, hamathecium, asci and ascospores were carried out by immersing ascomata in water or in 10% lactic acid. Microphotography was taken with material mounted in water, cotton blue, Melzer’s reagent or 10–100% lactic acid.

Terminologies are as in Ulloa and Hanlin (2000). In addition, ascomata size is defined as: small-sized: < 300 μm diam., medium-sized: from 300 μm to 600 μm diam., large-sized: > 600 μm diam.

Question mark (“?”) before family (or genus) name means its familial (or generic) status within Pleosporales (or some particular family) is uncertain. Other question marks after habitats, latin names or other substantives mean the correctness of their usages need verification.

Results

Molecular phylogeny

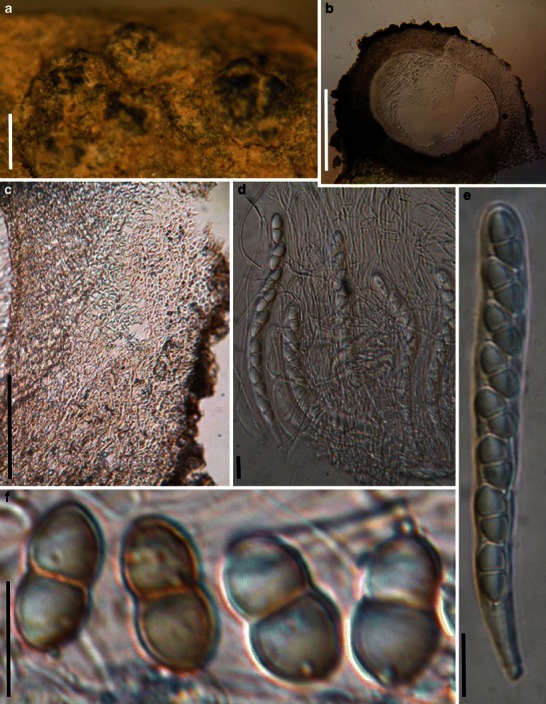

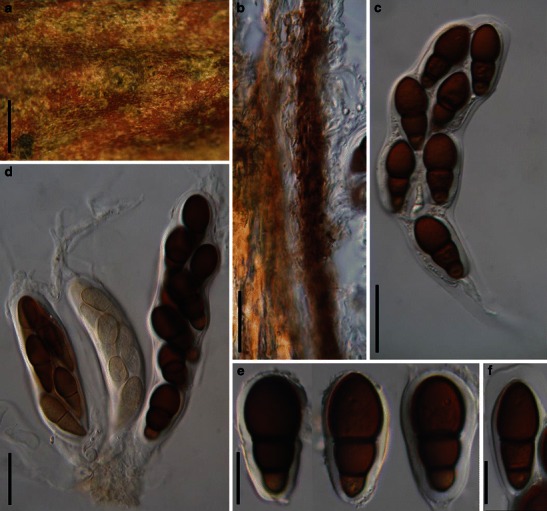

In total, 278 pleosporalean taxa are included in the phylogenetic analysis. These form 25 familial clades in the dendrogram, i.e. Aigialaceae, Amniculicolaceae, Arthopyreniaceae, Cucurbitariaceae/Didymosphaeriaceae, Delitschiaceae, Didymellaceae, Dothidotthiaceae, Hypsostromataceae, Lentitheciaceae, Leptosphaeriaceae, Lindgomycetaceae, Lophiostomataceae, Massariaceae, Massarinaceae, Melanommataceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae, Phaeosphaeriaceae, Pleomassariaceae, Pleosporaceae, Sporormiaceae, Testudinaceae/Platystomaceae, Tetraplosphaeriaceae, Trematosphaeriaceae and Zopfiaceae (Plate 1). Of these, Lentitheciaceae, Massarinaceae, Montagnulaceae, Morosphaeriaceae and Trematosphaeriaceae form a robust clade in the present study and in previous studies (Schoch et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009a, b). We thus emended the suborder, Massarineae, to accommodate them.

Pleosporales suborder Massarineae Barr, Mycologia 71: 948. (1979a). emend.

Habitat freshwater, marine or terrestrial environment, saprobic. Ascomata solitary, scattered or gregarious, globose, subglobose, conical to lenticular, immersed, erumpent to superficial, papillate, ostiolate. Hamathecium of dense or rarely few, filliform pseudoparaphyses. Asci bitunicate, fissitunicate, cylindrical, clavate or broadly clavate, pedicellate. Ascospores hyaline, pale brown or brown, 1 to 3 or more transverse septa, rarely muriform, narrowly fusoid, fusoid, broadly fusoid, symmetrical or asymmetrical, with or without sheath.

Accepted genera of Pleosporales

Acrocordiopsis Borse & K.D. Hyde, Mycotaxon 34: 535 (1989). (Pleosporales, genera incertae sedis)

Generic description

Habitat marine, saprobic. Ascomata seated in blackish stroma, scattered or gregarious, superficial, conical to semiglobose, ostiolate, carbonaceous. Hamathecium of dense, long trabeculate pseudoparaphyses. Asci 8-spored, cylindrical with pedicels and conspicuous ocular chambers. Ascospores hyaline, 1-septate, obovoid to broadly fusoid.

Anamorphs reported for genus: none.

Literature: Alias et al. 1999; Barr 1987a; Borse and Hyde 1989.

Type species

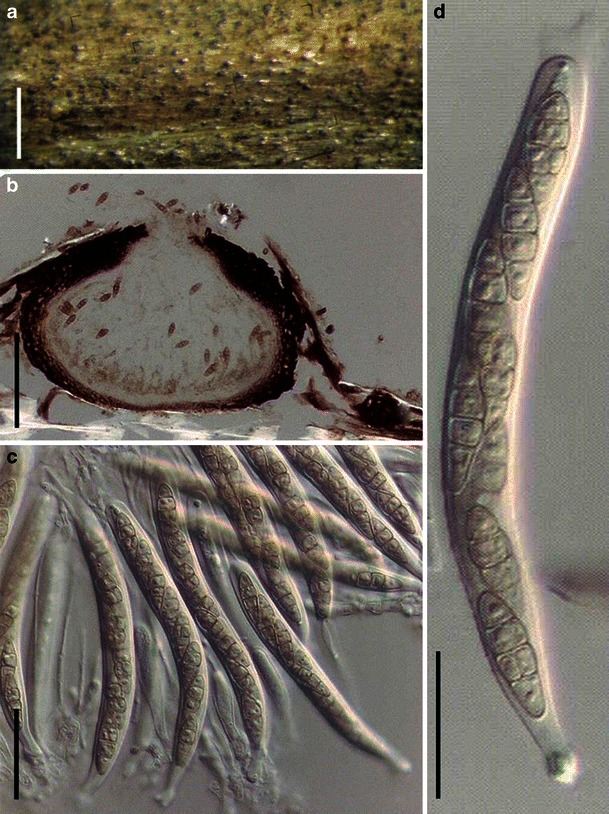

Acrocordiopsis patilii Borse & K.D. Hyde, Mycotaxon 34: 536 (1989). (Fig. 1)

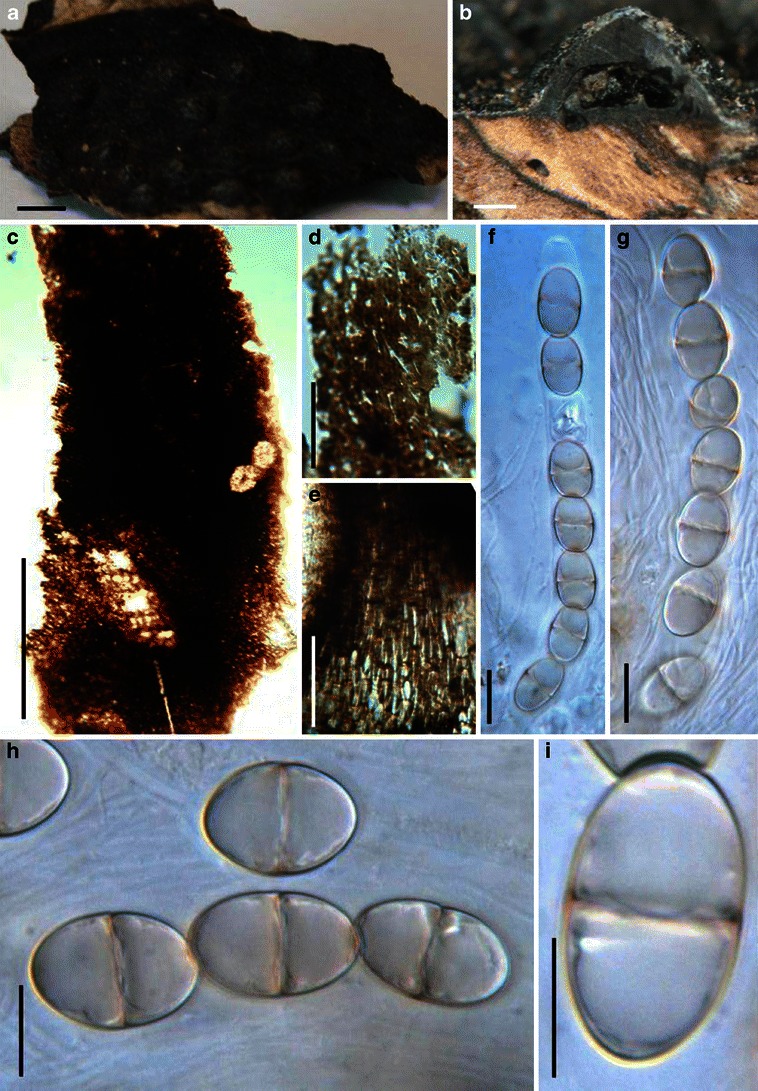

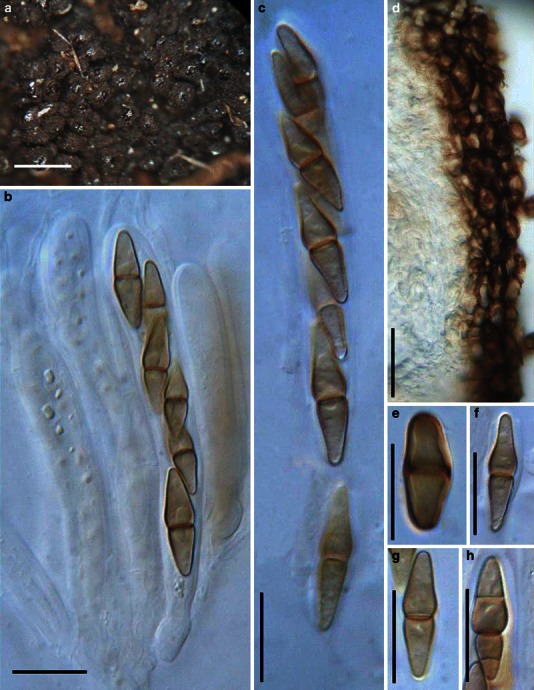

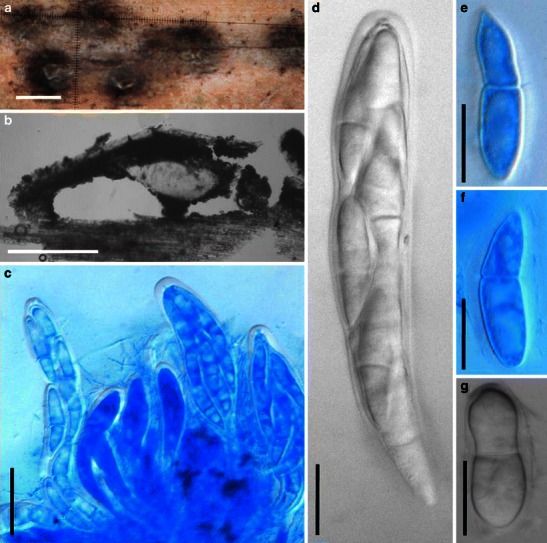

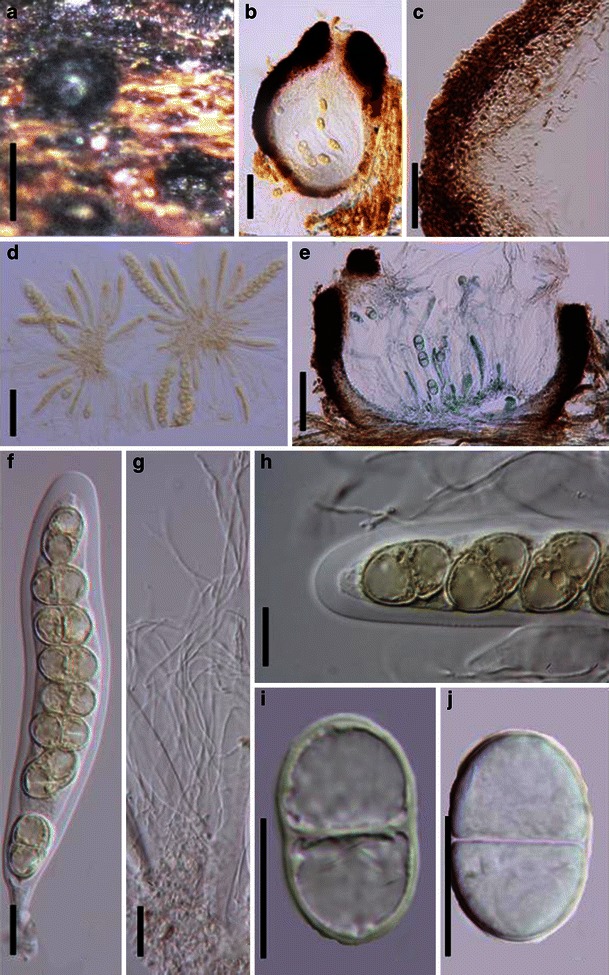

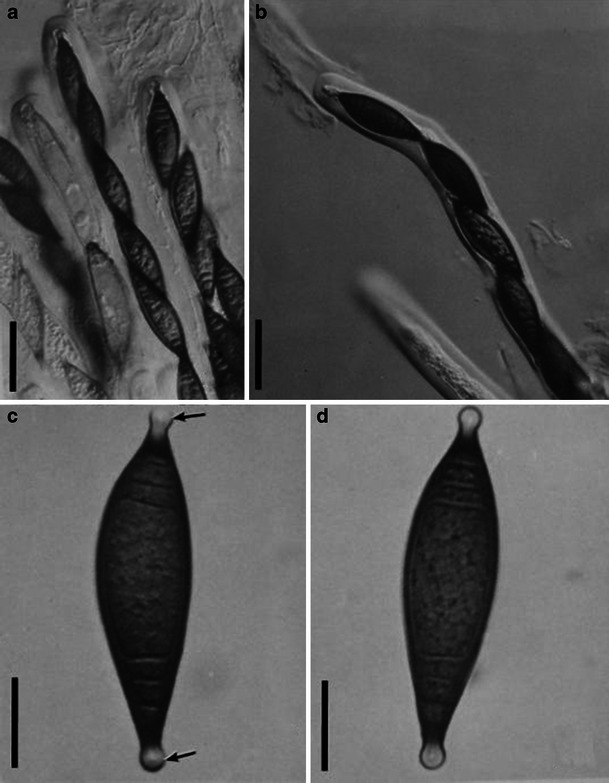

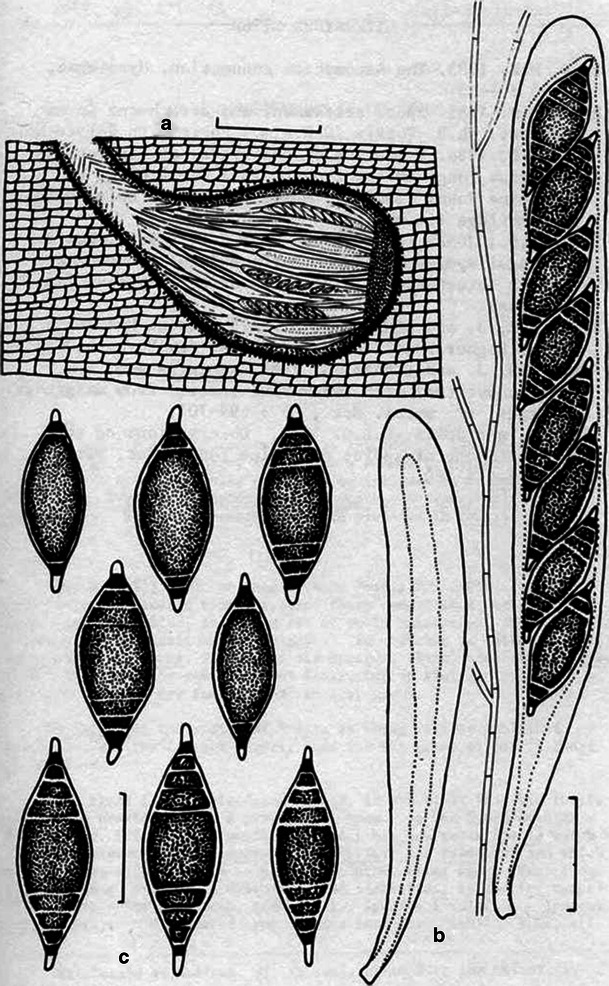

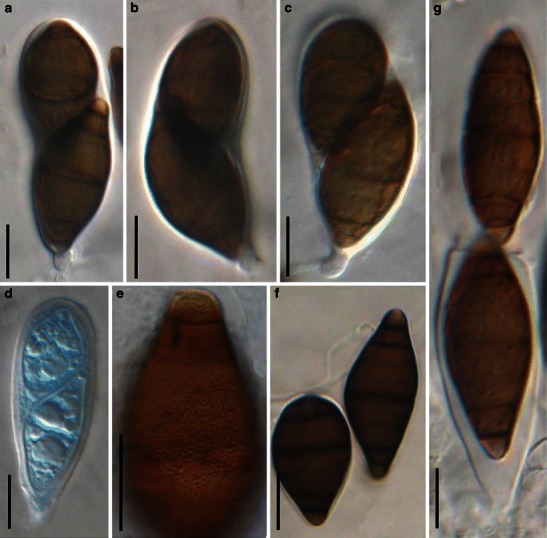

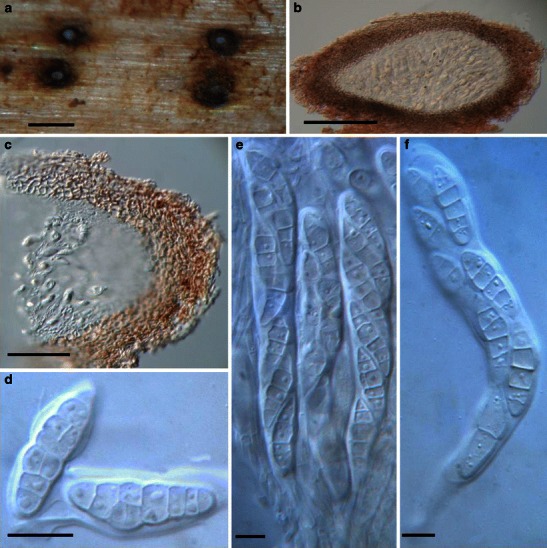

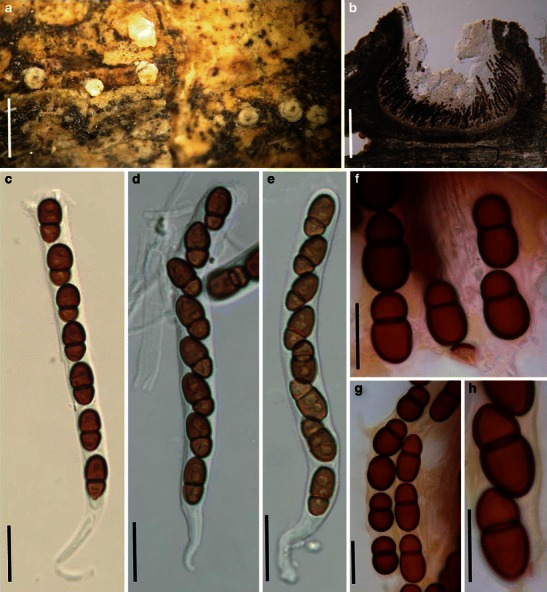

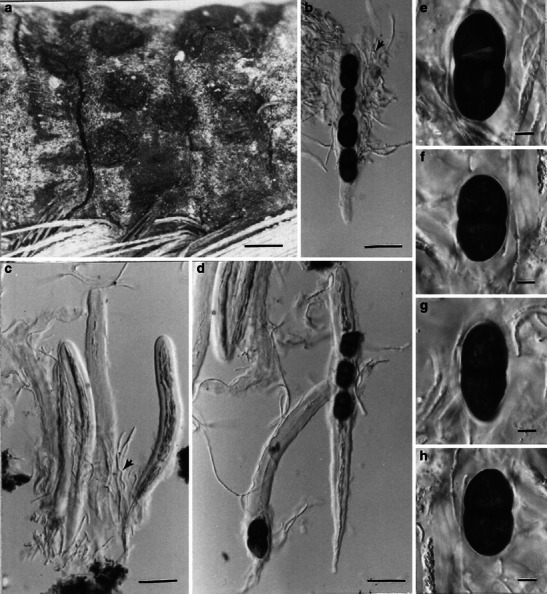

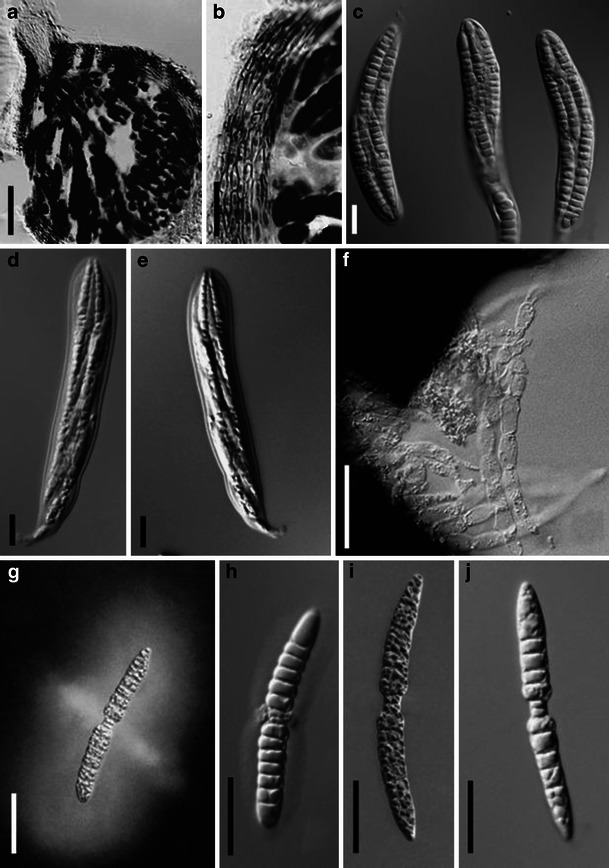

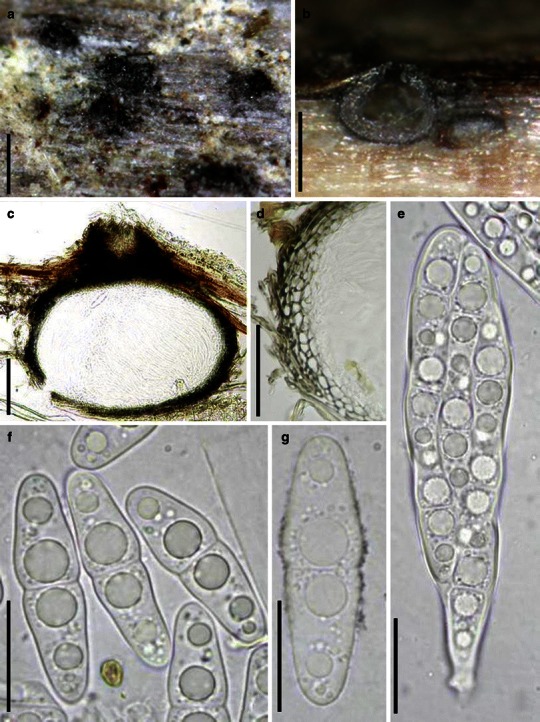

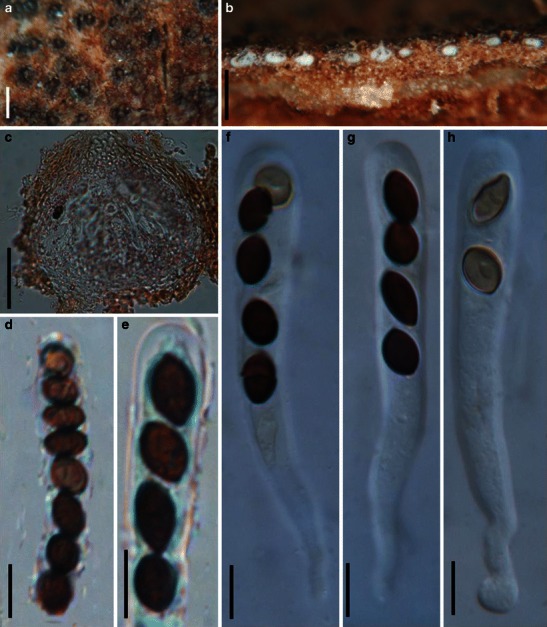

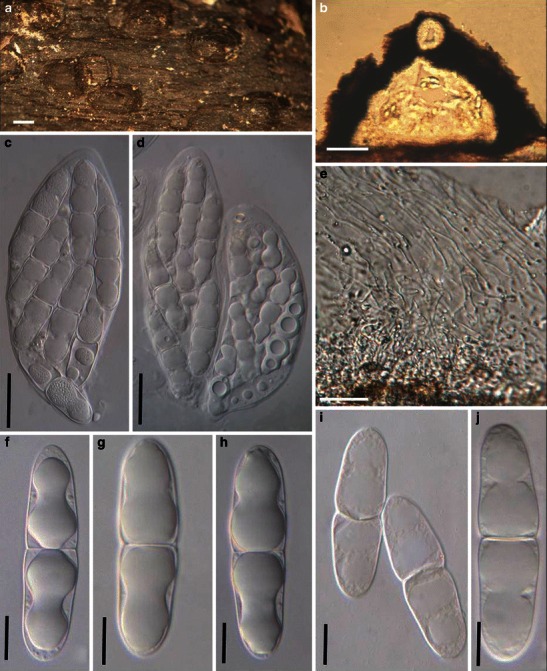

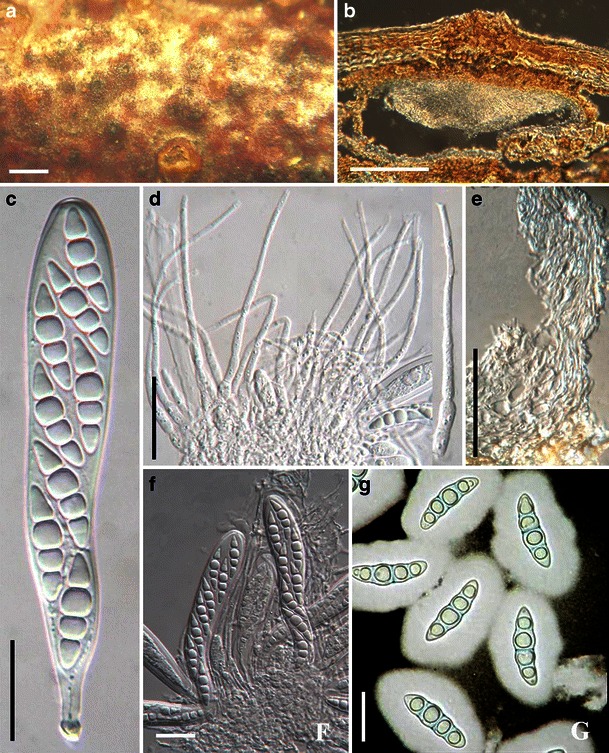

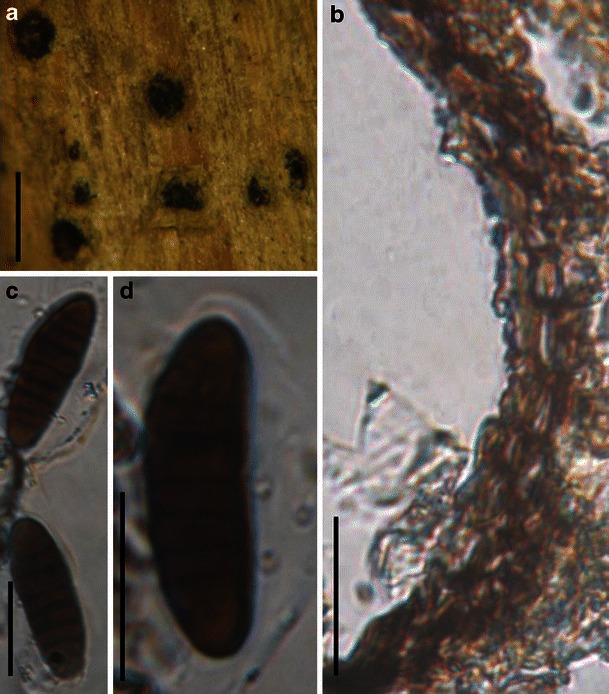

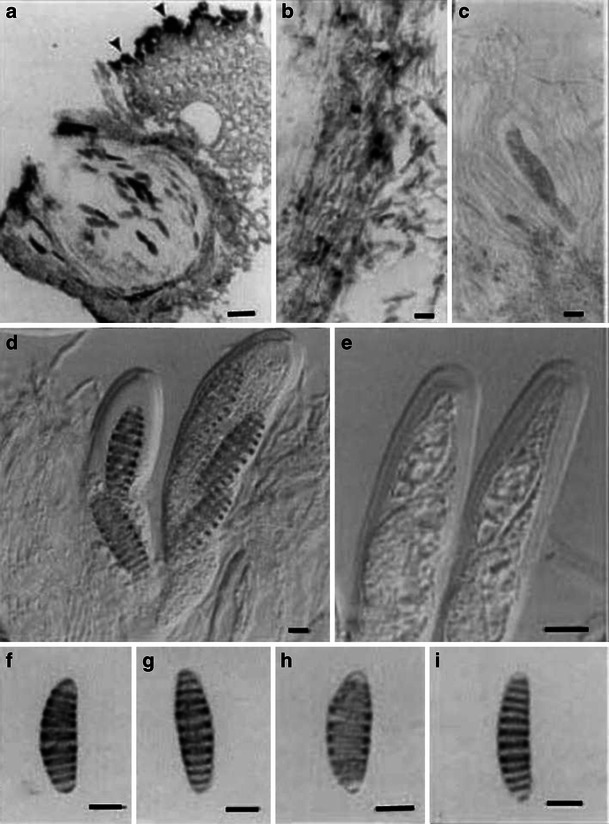

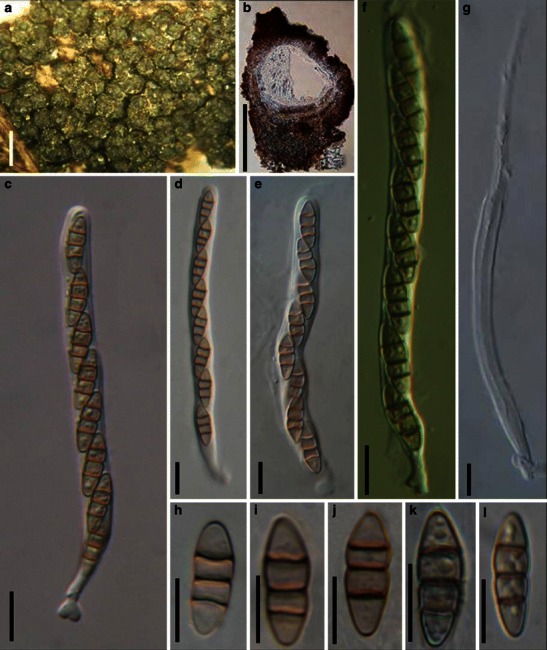

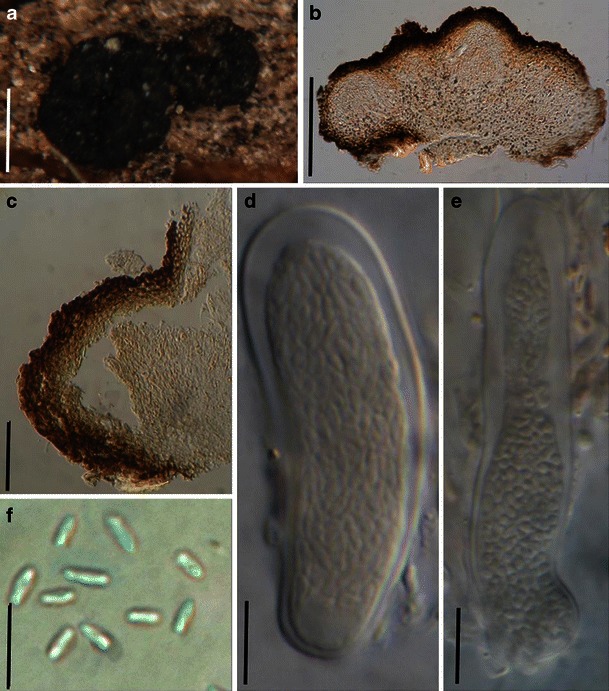

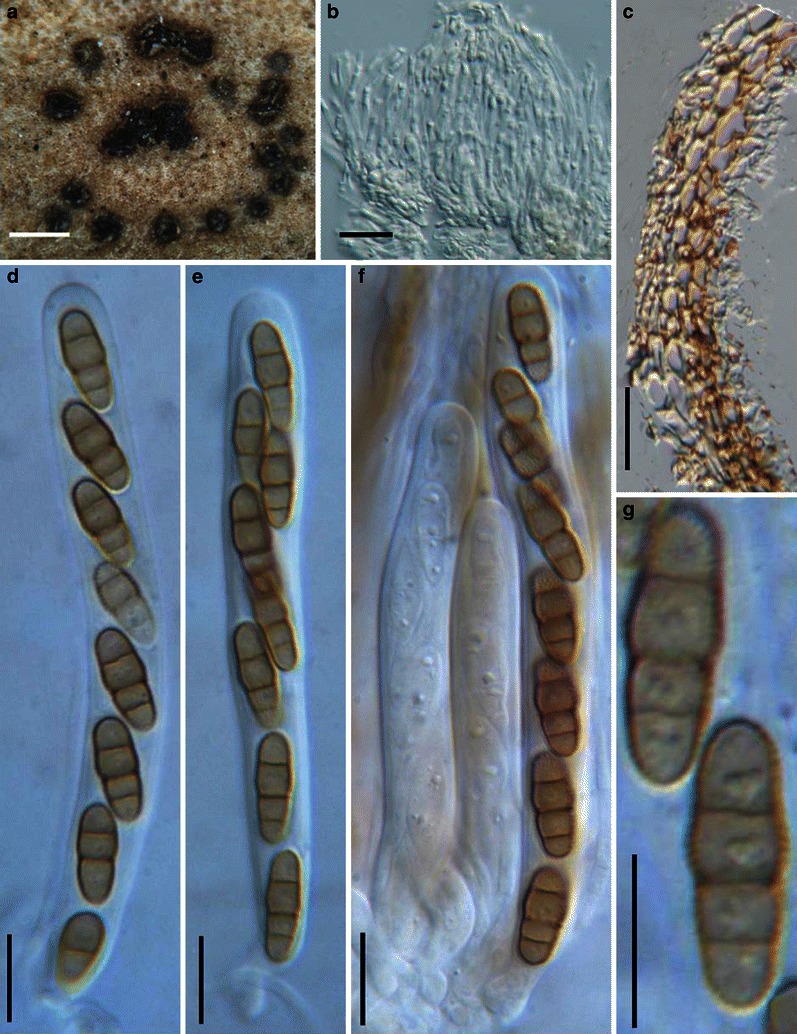

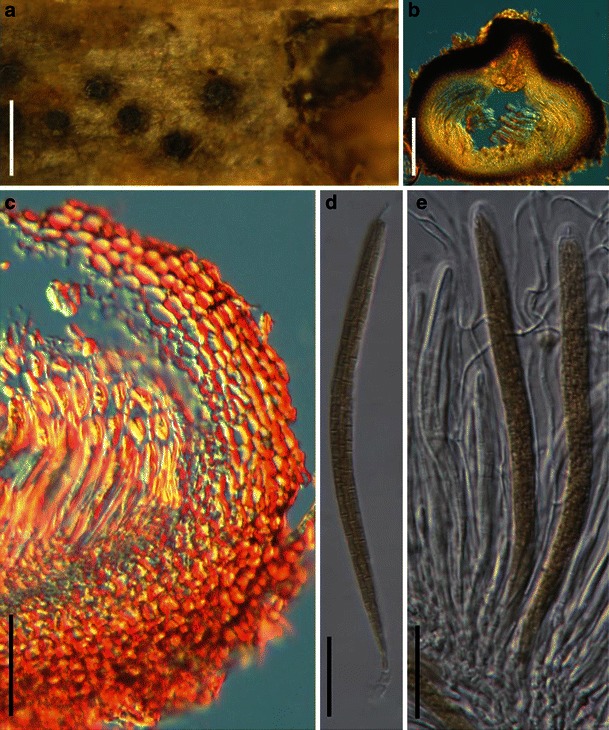

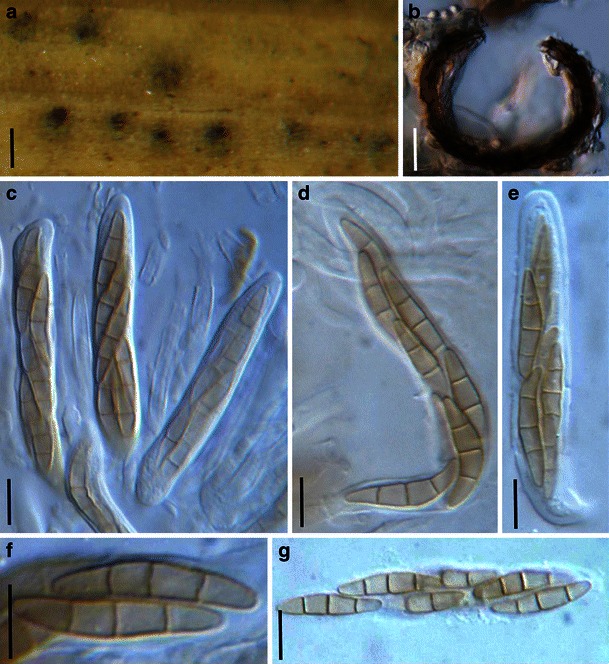

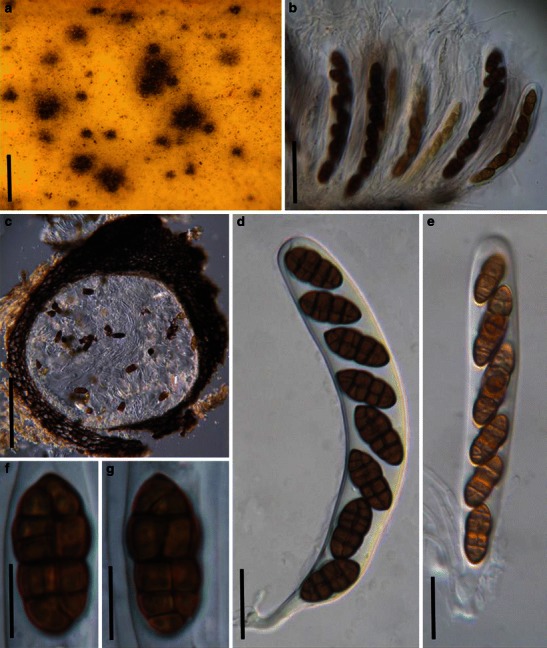

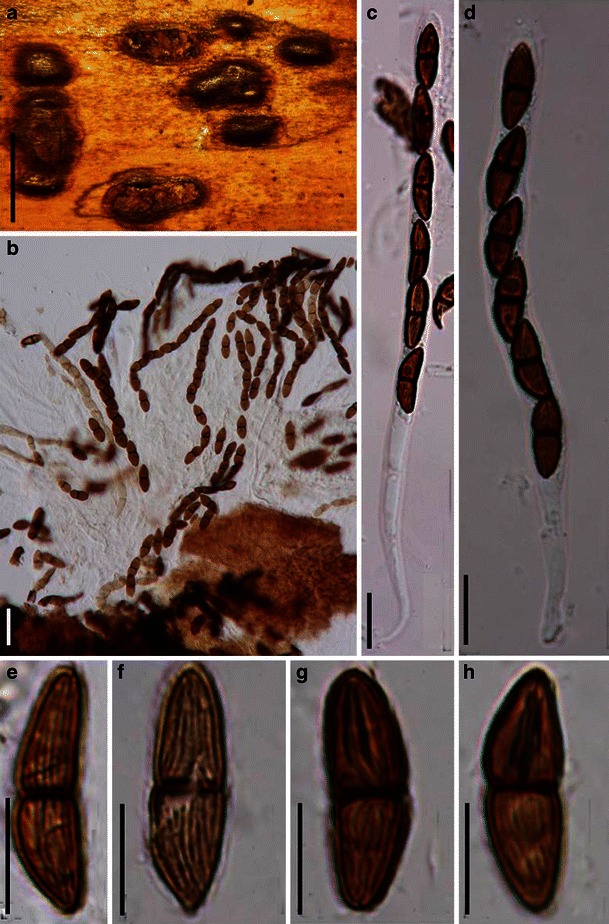

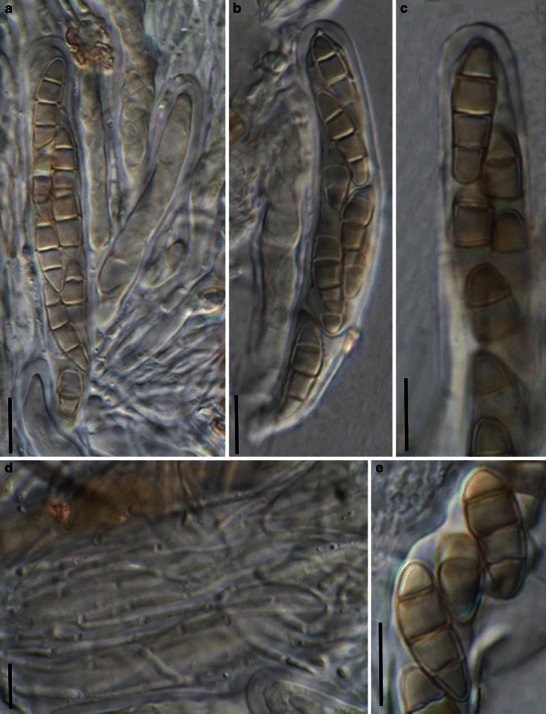

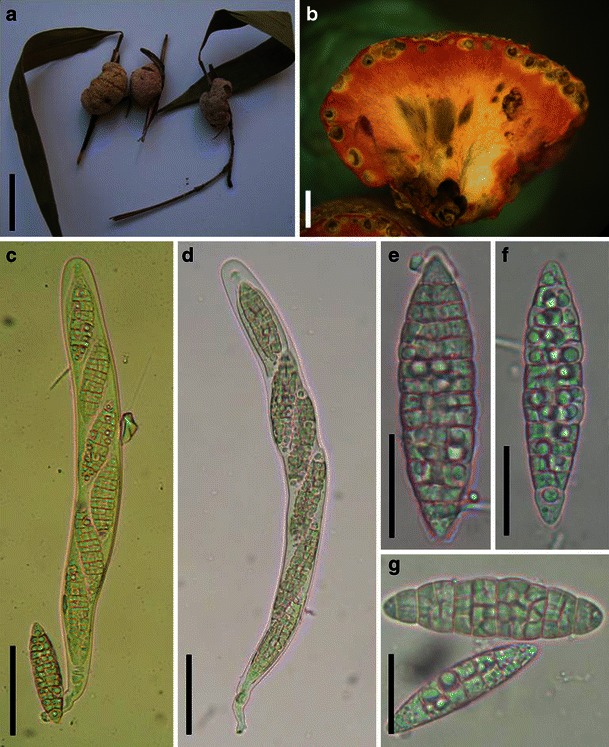

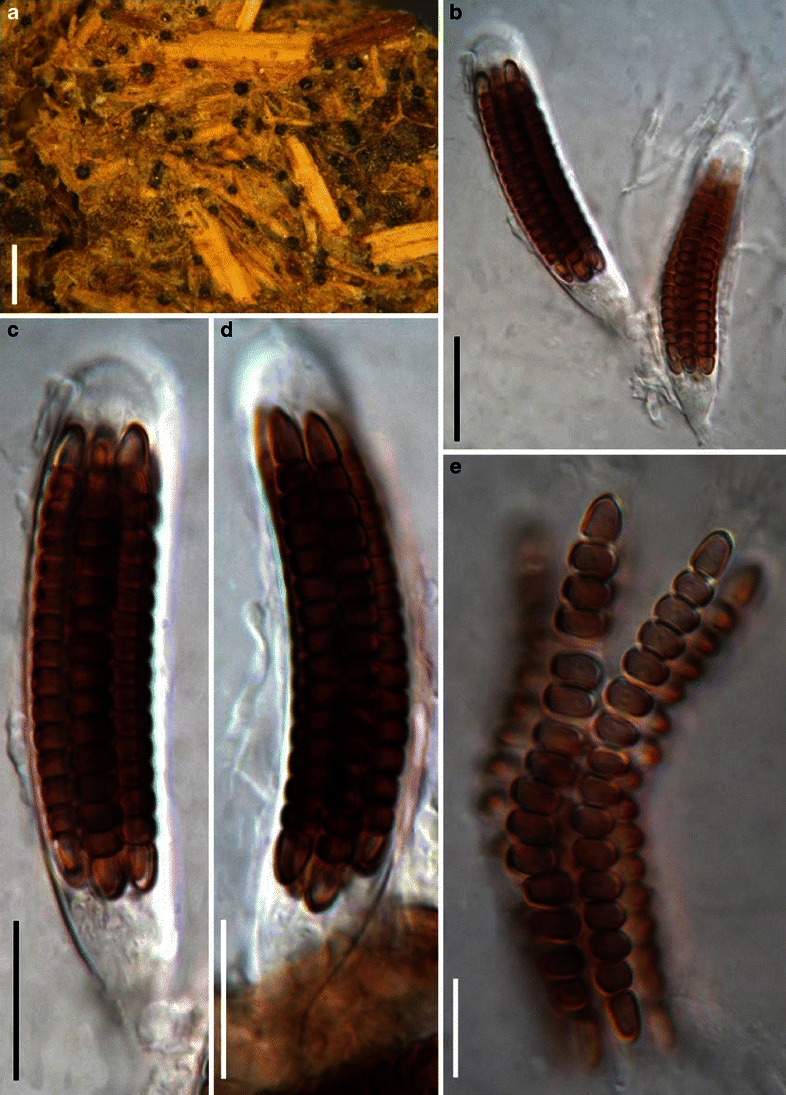

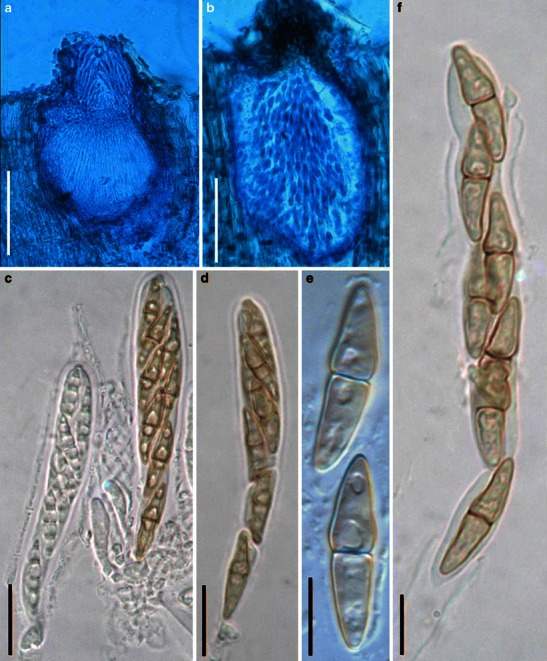

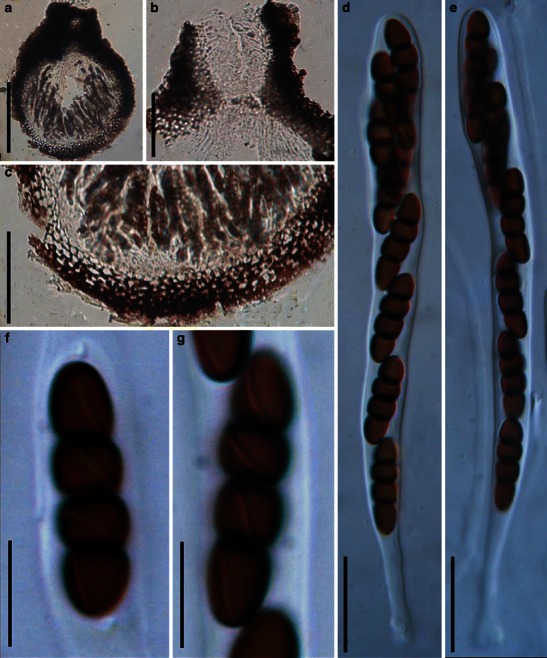

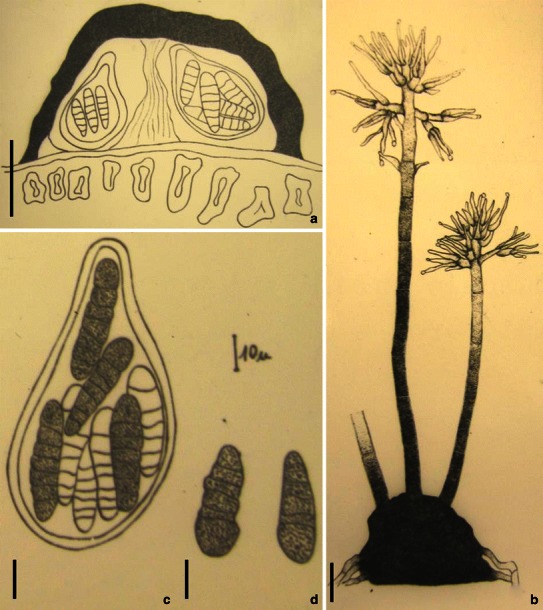

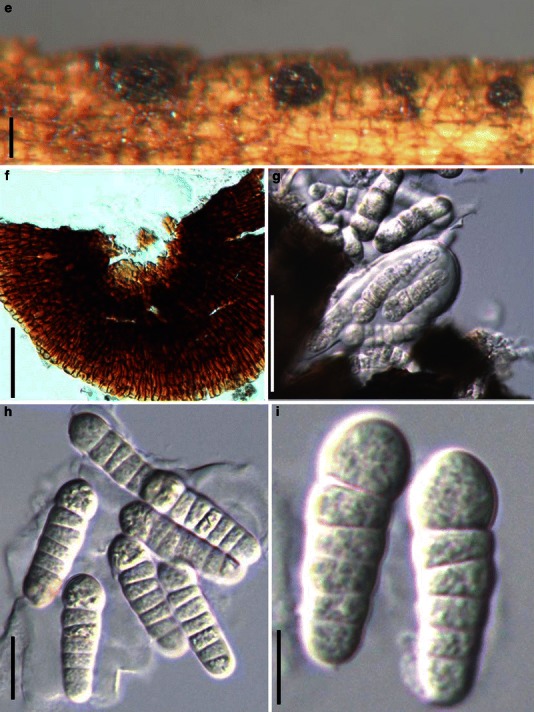

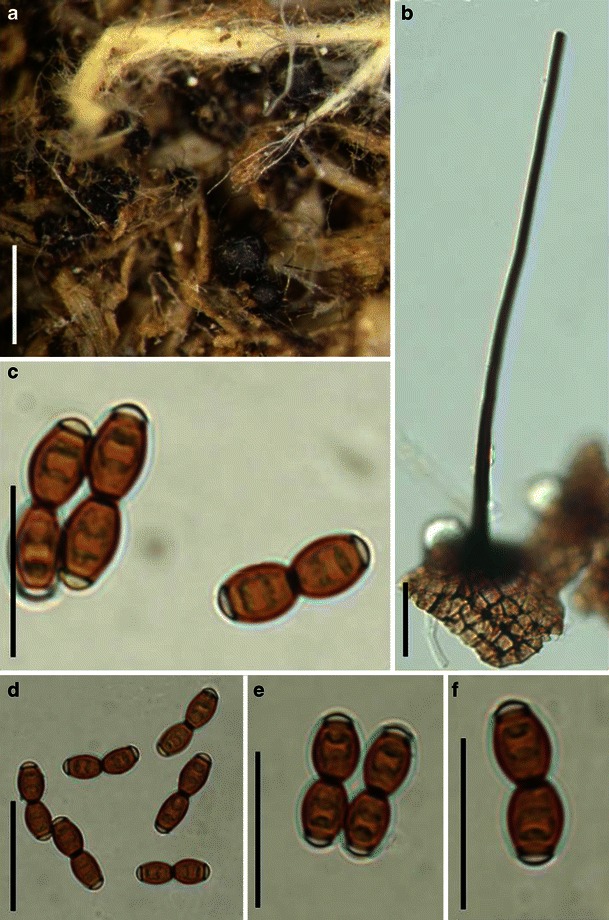

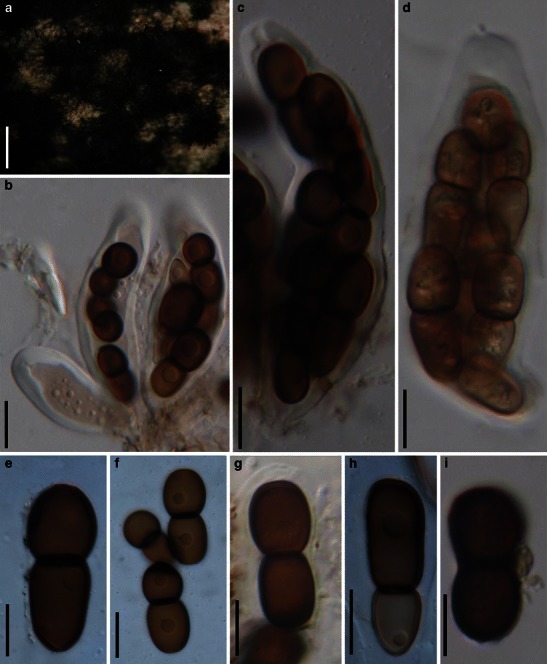

Fig. 1.

Acrocordiopsis patilii (from IMI 297769, holotype). a Ascomata on the host surface. b Section of an ascoma. c Section of lateral peridium. d Section of the apical peridium. e Section of the basal peridium. Note the paler cells of textura prismatica. f Cylindrical ascus. g Cylindrical ascus in pseudoparaphyses. h, i One-septate ascospores. Scale bars: a = 3 mm, b = 0.5 mm, c = 200 μm, d, e =50 μm, f, g = 20 μm

Ascomata 1–2 mm high × 1.8–3 mm diam., scattered or gregarious, superficial, conical or semiglobose, with a flattened base not easily removed from the substrate, ostiolate, black, very brittle and carbonaceous and extremely difficult to cut (Fig. 1a and b). Peridium 250–310 μm thick, to 600 μm thick near the apex, thinner at the base, comprising three types of cells; outer cells pseudoparenchymatous, small heavily pigmented thick-walled cells of textura epidermoidea, cells 0.6–1 × 6–10 μm diam., cell wall 5–9 μm thick; cells near the substrate less pigmented, composed of cells of textura prismatica, cell walls 1–3(−5) μm thick; inner cells less pigmented, comprised of hyaline to pale brown thin-walled cells, merging with pseudoparaphyses (Fig. 1c, d and e). Hamathecium of dense, long trabeculate pseudoparaphyses, ca. 1 μm broad, embedded in mucilage, hyaline, anastomosing and sparsely septate. Asci 140–220 × 13–17 μm (

Anamorph: none reported.

Material examined: INDIA, Indian Ocean, Malvan (Maharashtra), on intertidal wood of Avicennia alba Bl., 30 Oct. 1981 (IMI 297769, holotype).

Notes

Morphology Acrocordiopsis was formally established by Borse and Hyde (1989) as a monotypic genus represented by A. patilii based on its “conical or semiglobose superficial carbonaceous ascomata, trabeculate pseudoparaphyses, cylindrical, bitunicate, 8-spored asci, and hyaline, 1-septate, obovoid or ellipsoid ascospores”. Acrocordiopsis patilii was first collected from mangrove wood (Indian Ocean) as a marine fungus, and a second marine Acrocordiopsis species was reported subsequently from Philippines (Alias et al. 1999). Acrocordiopsis is assigned to Melanommataceae (Melanommatales sensu Barr 1983) based on its ostiolate ascomata and trabeculate pseudoparaphyses (Borse and Hyde 1989). Morphologically, Acrocordiopsis is similar to Astrosphaeriella sensu stricto based on the conical ascomata and the brittle, carbonaceous peridium composed of thick-walled black cells with rows of palisade-like parallel cells at the rim area. Ascospores of Astrosphaeriella are, however, elongate-fusoid, usually brown or reddish brown and surrounded by a gelatinous sheath when young; as such they are readily distinguishable from those of Acrocordiopsis. A new family (Acrocordiaceae) was introduced by Barr (1987a) to accommodate Acrocordiopsis. This proposal, however, has been rarely followed and Jones et al. (2009) assigned Acrocordiopsis to Melanommataceae.

Phylogenetic study

Acrocordiopsis patilii nested within an unresolved clade within Pleosporales (Suetrong et al. 2009). Thus its familial placement is unresolved, but use of the Acrocordiaceae could be reconsidered with more data.

Concluding remarks

Acrocordiopsis, Astrosphaeriella sensu stricto, Mamillisphaeria, Caryospora and Caryosporella are morphologically similar as all have very thick-walled carbonaceous ascomata, narrow pseudoparaphyses in a gelatinous matrix (trabeculae) and bitunicate, fissitunicate asci. Despite their similarities, the shape of asci and ascospores differs (e.g. Mamillisphaeria has sac-like asci and two types of ascospores, brown or hyaline, Astrosphaeriella has cylindro-clavate asci and narrowly fusoid ascospores, both Acrocordiopsis and Caryosporella has cylindrical asci, but ascospores of Caryosporella are reddish brown). Therefore, the current familial placement of Acrocordiopsis cannot be determined. All generic types of Astrosphaeriella sensu stricto, Mamillisphaeria and Caryospora should be recollected and isolated for phylogenetic study.

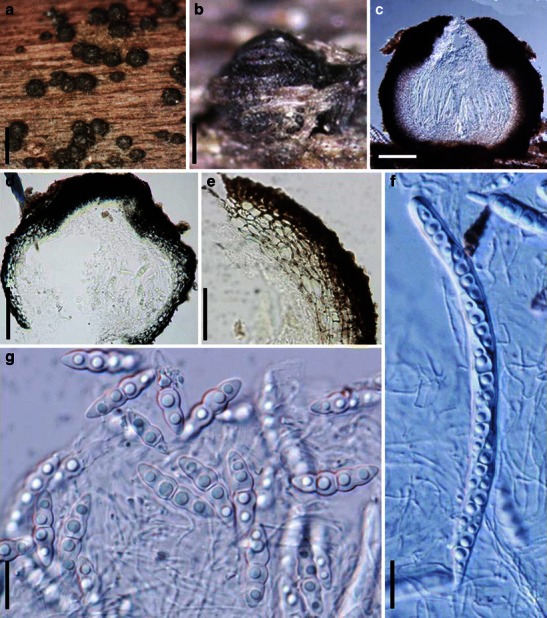

Aigialus Kohlm. & S. Schatz, Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 85: 699 (1985). (Aigialaceae)

Generic description