Abstract

Biobanks can have a pivotal role in elucidating disease etiology, translation, and advancing public health. However, meeting these challenges hinges on a critical shift in the way science is conducted and requires biobank harmonization. There is growing recognition that a common strategy is imperative to develop biobanking globally and effectively. To help guide this strategy, we articulate key principles, goals, and priorities underpinning a roadmap for global biobanking to accelerate health science, patient care, and public health. The need to manage and share very large amounts of data has driven innovations on many fronts. Although technological solutions are allowing biobanks to reach new levels of integration, increasingly powerful data-collection tools, analytical techniques, and the results they generate raise new ethical and legal issues and challenges, necessitating a reconsideration of previous policies, practices, and ethical norms. These manifold advances and the investments that support them are also fueling opportunities for biobanks to ultimately become integral parts of health-care systems in many countries. International harmonization to increase interoperability and sustainability are two strategic priorities for biobanking. Tackling these issues requires an environment favorably inclined toward scientific funding and equipped to address socio-ethical challenges. Cooperation and collaboration must extend beyond systems to enable the exchange of data and samples to strategic alliances between many organizations, including governmental bodies, funding agencies, public and private science enterprises, and other stakeholders, including patients. A common vision is required and we articulate the essential basis of such a vision herein.

Health-care systems worldwide are severely strained by the exponential growth of aging populations and the rising incidence of common chronic diseases. We face these public health challenges in a scientific era characterized by the emergence of novel technologies and tools that can improve the diagnosis, prevention, treatment and management of disease, and accelerate advances in personalized medicine. Realizing the potential of these technologies relies heavily on access to comprehensive and well-organized collections of human biological samples and associated clinical and research data. These collections, referred to as biobanks, provide the essential raw materials that fuel the contemporary advance of biotechnology, scientific and medical research, and improvements in both public health1 and individual patient care. The purpose of this white paper is to articulate a vision for global biobanking that calls for enhanced sharing and pooling of data from our biobanks to accelerate health research and translation.

Biobanking is not a new concept or field. Biospecimens have been collected and stored in conjunction with clinical and epidemiological studies for several decades. The principal departures from long-standing epidemiological tradition and past biobanking efforts include the number and size of the initiatives now underway and the emphasis on obtaining biological material together with a rich array of phenotypic information. The phenotypes being collected may include diagnoses, risk factors, physical and metabolic parameters (such as blood pressure and insulin resistance), other clinically relevant data, as well as data on behavioral and social factors. The availability of whole-genome technologies has significantly expanded the number of questions that can be addressed from the analysis of these collections. There has also been a substantial change in the national and international context for biobanking. In particular, modern biobanks are now recognized as important infrastructural platforms for specimen and data sharing, and not just as tools for single studies. This means that biobanks have to be designed, constructed, funded and managed with flexibility, sustainability, and international interoperability. Moreover, because of the rapid developments in science and technology, future uses of specimens and data cannot be fully anticipated when a biobank is first established. This presents a number of major scientific, logistic, ethico-legal, and political challenges,2 and has important implications for the design, operation, and utilization of biobanks.

Optimizing our ability to harness the full potential of human biobanks for the betterment of global human health requires the support of exploratory approaches and research infrastructures that do not fit traditional models of hypothesis-driven research. The shift to highly parallel investigational approaches and tools is already underway. It requires coordination and cooperation between a diversity of stakeholders, including policy makers and funders. Under this new model, funding for research data, biological samples, and the infrastructures needed to maximize their scientific utility is viewed as an investment that will benefit the public. This is illustrated by the recent joint statement of purpose issued by seventeen major funders of health research, which endorses sharing data to improve public health.3 Although we outline an ambitious agenda, considerable momentum has already been generated as illustrated by the diverse types of international activities listed in Table 1. Importantly, the development of biobanking resources and infrastructures, as proposed herein, should not be viewed as competing against or replacing hypothesis-driven research, but rather as essential tools that facilitate and support such research.

Table 1. Examples of organizations, initiatives, and resources supporting the development of harmonized platforms for biobanks and biobank-based science.

| Entity | Description and web link |

|---|---|

| Regional and international organizations | |

| ESBB | The European, Middle Eastern & African Society for Biopreservation & Biobanking, a regional chapter of ISBER, aims to advance the field of biobanking in support of research related to healthcare, education, and the environment. (http://www.esbb.org) |

| FIBO | The Forum for International Biobanking Organizations aims to improve biomedical research by enhancing interactions between organizations involved in human biobanking at a global level. (http://www.isber.org/Partnerships/fibo.cfm) |

| IARC | The International Agency for Research on Cancer coordinates and conducts research on the cause of human cancer and the mechanisms of carcinogenesis, and develops scientific strategies for cancer prevention and control. (http:www.iarc.fr) |

| ISBER | The International Society for Biological And Environmental Repositories is a forum promoting quality standards and ethical principles and innovation in biospecimen banking. (http://www.isber.org) |

| Marble Arch WG | The Marble Arch Working Group aims to harmonize approaches in regional and national biobanks and address critical issues in managing a modern human specimen biobank. (http://www.oncoreuk.org) |

| OECD | The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development is an international organization helping governments tackle the economic, social, and governance challenges of a globalized economy. (http://www.oecd.org) |

| P3G | The Public Population Project in Genomics is an international consortium with members in 40 countries. It aims to lead, catalyze, and coordinate international efforts and expertise, so as to optimize the use of studies, biobanks, research databases, and other similar health and social research infrastructures. (ttp://www.p3g.org) |

| Science and infrastructure initiatives | |

| BBMRI | The European Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure aims to create a pan-European research infrastructure for biobanking. (www.bbmri.eu) |

| The Biomarkers Consortium | The Biomarkers Consortium is a public–private biomedical research partnership that endeavors to develop, validate, and qualify biological markers (biomarkers) to speed the development of medicines and therapies for detection, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease and improve patient care. (http://www.biomarkersconsortium.org) |

| BioSHaRE-EU | The BioSHaRE-EU project aims to achieve solutions for researchers to use pooled data from different cohort and biobank studies. (http://www.bioshare.eu) |

| caBIG | The Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid aims to develop a collaborative information network that accelerates the discovery of new approaches for the detection, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer. (https://cabig.nci.nih.gov/) |

| caHUB | The Cancer Human Biobank aims to advance cancer research and treatment through development of a national center for biospecimen science and standards. (http://cahub.cancer.gov/) |

| CPT | The Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project aims to establish a platform to facilitate research into the interplay between genes, lifestyle and environment, and subsequent impact on risk of cancer and other chronic diseases in Canadian adults. (http://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca) |

| EATRIS | The European Advanced Translational Research Infrastructure in medicine aims at translating research findings into improved diagnosis, disease prevention, and treatment. (http://www.eatris.eu) |

| ECRIN | The European Clinical Research Infrastructure project aims to implement a research infrastructure accessible to all clinical researchers in the EU member and associated states.(http://www.ecrin.org) |

| Gen2Phen | The Human Genome Variation Genotype-to-Phenotype database aims to unify human and model organism genetic variation databases. (http:www.gen2phen.org) |

| GraPH-Int | The Genome-based Research and Population Health International Network is a global collaboration of individuals and organizations with an interest in public health genomics. (http://www.graphint.org) |

| ICGC | The International Cancer Genome Consortium aims to obtain a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes which are of clinical and societal importance across the globe. (http://www.icgc.org/) |

| The Human Epigenome Project | The Human Epigenome Project is a public/private collaboration that aims to identify and catalog Methylation Variable Positions (MVPs) in the human genome. (http://www.epigenome.org/index.php) |

| The Human Variome Project | The Human Variome Project is a global initiative to collect and curate all human genetic variation affecting human health. (http://www.humanvariomeproject.org/) |

| HuGENet | The Human Genome Epidemiology Network is a global collaboration of individuals and organizations committed to the assessment of the impact of human genome variation on population health. (http://www.hugenet.org.uk) |

| PHGEN II | PHGEN II builds on the experiences of PHGEN I (Public Health Genomics European Network), which was a networking exercise to develop a common understanding of Public Health Genomics between all stakeholders in Europe. (http://www.phgen.eu/typo3/index.php?id=103) |

| PHOEBE | The Promoting Harmonization for Epidemiological Biobanks project aims to establish a collaborative research network to identify and explore key issues related to the use of population-based biobanks and longitudinal cohort studies. (http://www.phoebe-eu.org) |

| UKDBN | The UK DNA Banking Network aims to support genetic epidemiology in the translation of the human genome sequence into health benefits. (http://www.dna-network.ac.uk) |

| OECI-Tubafrost | The European Human Tumor Frozen Tissue Bank collects information on human material ie frozen tumor tissue specimens, pathology blocks, blood samples in different forms, cell lines, and Tissue Micro Arrays. (ttp://www.tubafrost.org) |

| Resource tools and databases | |

| dbGap | The Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes is a public repository for individual-level phenotype, exposure, genotype and sequence data and the associations between them. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap>) |

| DataSHaPER | The Data Schema and Harmonization Platform for Epidemiological Research is a tool aiming to facilitate the harmonization of studies. (http://www.datashaper.org) |

| DataSHIELD | The Data Aggregation Through Anonymous Summary-statistics from Harmonized Individual-levEL Databases provides a novel approach to data synthesis, based on parallel processing and distributed computing. (http://www.p3gobservatory.org) |

| ENCODE | The ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements project aims to identify all functional elements in the human genome sequence. (http://www.genome.gov) |

| ESPRESSO-forte Power Calculator | ESPRESSO (The Estimating Sample-size and Power in R by Exploring Simulated Study Outcomes) is a new ‘R'-based program for simulation-based power calculation that can be used to estimate realistic sample-size requirements for case–control and cohort studies in population genomics where analysis focuses on either direct genetic or environmental effects or interactions. (http://www.p3gobservatory.org) |

| HapMap | The International HapMap Project is a joint effort to identify and catalog genetic similarities and differences between human beings. (http://www.hapmap.org) |

| HUMGEN | The HUMGEN International Database is a resource concerning ethical, legal, and social issues in human genetics. (http://www.humgen.org/int/) |

| PhenX | The Consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures project aims to contribute to the integration of genetics and epidemiologic research. (http://www.phenx.org) |

| OBIBA | The Open Source Software for Biobanks is a collaborative international project whose mission is to build high-quality open source software for biobanks. (http://www.obiba.org) |

| OBO | The Open Biological and Biomedical Ontologies project aims to establish a set of principles for ontology development with the goal of creating a suite of orthogonal interoperable reference ontologies in the biomedical domain. (http://www.obofoundry.org/) |

| P3G Catalogs | The P3G catalogs provide access to information about large population-based biobanks. (http://www.p3gobservatory.org) |

| SPIDIA | The SPIDIA (Standardization and improvement of generic preanalytical tools and procedures for in vitro diagnostics) project aims to provide the scientific basis for European standards and norms for sample preanalytics. (http://www.spidia.eu) |

| STORE | The STORE (Sustaining access to tissues and data from radiobiological experiments) project aims to create a platform for the storage and dissemination of both data and biological materials from past, present, and future radiobiological research. (http://fp7store.de/pages/home.php?lang=EN) |

| TISS.EU | The Tiss.EU project aims to analyze the impact of current EU legislation and guidelines on biomedical research. (http://www.tisseu.uni-hannover.de/) |

The vision we articulate requires harmonization with the goal of interoperability. The science of biobanking, its management, and the political and social considerations that affect its sustainability are no less important. Below, we address harmonization, scientific considerations, ethical, legal and societal implications (ELSI), and sustainability in detail, as a basis for further discussion.

Harmonization

Harmonization of biobanking operational procedures and best practices is an essential element that enables biobanks to exchange and pool data and samples. This so-called interoperability is the foundation of successful global biobanking. Rather than demanding complete uniformity among biobanks, harmonization is a more flexible approach aimed at ensuring the effective interchange of valid information and samples.4, 5 One critical task of the harmonization process is to articulate those situations in which true standardization is required. Standardization implies that precisely the same protocols/standard operating procedures (SOPs) are used by all biobanks. For example, if data are to be passed between biobank databases then there needs to be agreement on standard ontologies and exchange formats. Likewise, comparison of high-throughput-technology-derived data requires that platforms and operational details be identical. Harmonization is context-specific and pertains to the compatibility of methodologies and approaches to facilitate synergistic work. It thereby relates to the critical areas of generating, sharing, pooling, and analyzing data and biological samples to allow combining resources and comparing results obtained from different biobanks. Harmonization encompasses enabling technologies and procedures for phenotype characterization, sample handling, in vitro assays, computational biology analytical tools and algorithms, data-coding and electronic-communication protocols that enable biobanks to network together within compatible ethico-legal frameworks.

In recognition of the necessity to synchronize efforts and build upon previous achievements, a host of consortia-based initiatives, project teams and agencies (Table 1) have been working to optimize the establishment, operation, and use of interoperative biobank resources globally as demonstrated by the Public Population Project in Genomics and Society.6 Toward this end, best practices for biobanking have been developed by several organizations and groups.7, 8, 9 The fundamental principles guiding these efforts include transparency, complementarity, and the sharing of relevant knowledge and tools to enable cutting-edge and translational science for the benefit of all. Harmonization initiatives have brought together individuals with diverse expertise. On the basis of consensus, they have developed standards,10, 11 tools, technologies, and resources, which are widely available to the biobanking community today. Indeed, the science of biobanking has emerged as a field in its own right, providing an ever-growing armamentarium of tools, information, compatible bioinformatics, and SOPs. However, progress in unraveling the complexities of disease etiology and developing successful treatments will require a far greater degree of knowledge and data integration than currently exists. Thus, how we structure and harmonize our biobanks today will have important impact on the future of biomedicine.

Not all biobanks have the same purpose or design. A typology of biobanks includes: (1) residual specimens collected during routine clinical care for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes, including collections of tumor samples with associated histopathologic, demographic, clinical, and outcome data; (2) specimens collected during clinical trials; (3) specimens collected as part of specific research projects; and (4) specimens collected as part of population-based biobanks, which often contain longitudinal components. These diverse types of biobanks have different roles in the generation and translation of knowledge into public health and clinical medicine, and technological plus conceptual evolution may make it impossible or undesirable to harmonize completely their practices, policies, and operations. Nonetheless, some baseline level of harmonization should be fostered for two main reasons. First, harmonization increases the quantity of usable data and numbers of biospecimens to achieve levels of statistical power necessary to detect effects underlying complex disease etiology.12, 13, 14, 15 Second, translational science will rely on fundamental biological data to (re)classify human disease on the basis of causality and to identify relevant drug targets and biomarkers.16 Effective planning of studies will use targeted investigations of specific groups classified on their individual, detailed biological – as well as socio-cultural – profiles. Such designs will enrich our analytical repertoire and may help overcome some of the historical boundaries between clinical and nonclinical research. Accordingly, our ability to correlate data and biospecimens from different biobanks will be pivotal to accelerating the pace of translational research. A meta-model to describe information about a biobank is already under construction as a first-step data sharing among biobanks that exhibit tremendous heterogeneities. This work is being conducted internationally to help harmonize the national biobanks participating in the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructures Initiative (BBMRI).17 Information about the participating biobanks is captured by a common set of attributes (minimum data set) designed to adopt different kinds of collections. The latest interoperability and semantic web technologies can be used for building resource description frameworks for data and services providing flexible frameworks that can be used in different data-sharing scenarios.

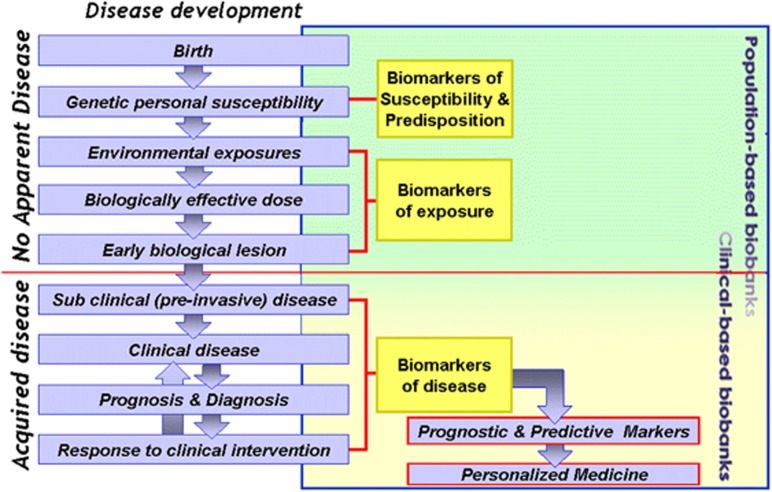

Figure 1 depicts three major types of biobanks and their niches in health-care research relative to population disease development. Modern research strategies should be able to draw on samples and data derived from these biobank categories to capture the full range of biological variance associated with phenotypes ranging from pre-disease states through response to treatment.

Figure 1.

Overview of the three major types of biobanks and their niches in health-care research relative to population disease development and their possible future cooperative role.

Scientific considerations

To ensure scientific excellence while optimally leveraging the potential of biobanks, the scientific frameworks within which biobanks operate will need to keep advancing in several critical areas, including: (1) networking of multidisciplinary professionals; (2) development of comprehensive inventories, including listing of extant biobanks, their holdings, and access procedures; (3) establishment of standardized data-collection protocols governed by appropriate quality management systems; (4) continued innovation that leads to improved technologies for preservation of biospecimens and pre-analytical processes, (5) progress in information infrastructure to facilitate data sharing and pooling, including new technical solutions for data management and analysis, as well as for the protection of participant privacy and data confidentiality; and (6) harmonization of quality management systems to ensure consistency of materials.

The science of biobanking itself is as important to develop and fund as the science that uses biobanks. Because the science of biobanking is very closely linked to the development of an enabling infrastructure, it requires scientists to work more closely with each other and with funders than has historically been the norm in biomedical science. In this, biobanking resembles more the situation typical for large-scale physics, which is characterized by close collaborative, pre-competitive relationships among workers in the field to construct, develop, and maintain the necessary research infrastructures while embracing healthy competition in the undertaking of both hypothesis-based and free research using these infrastructures. Developing this kind of culture and spirit will be essential for the success of large, cross-institutional biobanking efforts.

Meeting these needs will require stable funding and new mechanisms to support the coordination of infrastructure programs internationally.18 Other elements essential to the successful nurturing of a vibrant research community include frequent interchanges that will seed and foster relationships among scientists in the field, non-risk-averse early funding for small exploratory research projects, and the maintenance of registries of relevant professionals. Several of the major initiatives listed in Table 1 are already helping to meet these needs. However, they currently lack the kind of stable funding required not only for the activities listed above, but – importantly – also for the development of networking among biobanking professionals that can lead to the development of multidisciplinary research projects.

Training of the next generation of biobanking professionals is a critical aspect that requires focused attention and investment, as is the establishment of communication and publishing conduits for sharing resources and results. Specific attention will also need to be paid to career development and advancement aspects of biobanking scientists in an effort to correct the current perception of the profession as mere infrastructure providers. Likewise, the field itself still needs to build reputation and recognition as a scientific discipline as opposed to an ‘ancillary service'.

Ethical, societal, and policy considerations

No less important than harmonization of specimens and data is the promotion and implementation of shared ethical principles and procedures as they relate to biobanking. Although the last decade has seen the emergence of principles reflecting shared ethical principles that foster international scientific collaborations,19 the concepts of altruism, of solidarity,20, 21 or of databases as global ‘public goods'22, 23 to promote data sharing,24 are still evolving.25 Building trust, so that individuals will continue to donate to biobanks for the benefit of all, is essential to ensure the advance of biomedical research. Society must recognize its role in this process and take steps to protect research participants against the possible misuse of their information. This will require building governance mechanisms that operate at a meta-level to enable accountable and responsible research. Furthermore, we must develop approaches to foster trust related to specific contexts with which biobanks will interface, including, for example, industry and health care.

The authors strongly advocate that the necessary procedural mechanisms for privacy protection and the use of IT software and biostatistical solutions to facilitate secure use26 and transfer of data across borders27 be adopted and implemented more broadly by the global biobanking community as a matter of high priority. In addition, it will be important to build the mutual trust that is required for the delegation of ethics review across jurisdictions, where such delegation is feasible and appropriate.28 The use of researcher authentication techniques may provide additional protections and can be expected to develop gradually. For example, the Open Researcher and Contributor ID initiative enables institutionally verifiable and reliable disambiguation of one author from another.29 The mandatory deposition of certain data into the public domain and publication policies of journals enforcing transparency on these issues constitute important steps in these directions.30

In order to build a global infrastructure involving high-quality specimens and data collections to support a broad array of scientific projects, a highly supportive political environment is also critical. Strengthening relationships with governments, ministries, industry, and the general public will be crucial to create and maintain such an environment. Developing a global biobanking infrastructure is expensive and relies on the willingness of individual participants to act as ‘global citizens' – or as ‘citizen scientists'31 – by providing their specimens and data for the greater good of science and progress in individual and public health. Consideration should be given to working closely with agencies that communicate effectively the importance of science to educate the media and the general public. It is the responsibility of stakeholders to react sensitively and responsively to public and political perceptions and to maintain transparent, accountable information on their activities.7 In particular, general information on projects of researchers who have used the biobanks should be publically available.32

An important element of infrastructural development involves substantial investment in ensuring ethical, effective, and equitable access to banked data and samples. This often involves overlapping, but sometimes competing interests of biobank scientists and managers, secondary users of the biobank, study participants, funders, ethico-legal experts, and the public at large. Such a multiplicity of stakeholders means that some issues can only be resolved at the highest level, with agreement on policy at an international level after significant stakeholder input. Solutions include recognizing that data/samples funded from public funds are a shared resource for the promotion of scientific research for the public good, with adequate funding/cooperation and recognition of the contributions, which make these resources available, and with the provision of sanctions for those that misuse biobanks and/or specimens and data.24 To this end, the biobanking community and funders must work together with policy makers on regional, national, and international levels to provide legal and ethical frameworks or, at minimum, reciprocal ‘safe harbor' recognition to encourage the use and sharing of data, samples, and knowledge. This will require international consensus guidance and collaboration to ensure equitable approaches to the governance of privacy and access and the development of training programmes for members of ethics review boards and other data regulatory bodies. Current challenges are often related to the application of existing regulations and policies that were developed for patient safety and protection in interventional clinical trials involving new, potentially harmful drugs, devices, or psychological interventions; we argue that these norms are ill-suited for application to observational studies such as longitudinal population studies, with minimal risks (related primarily to data protection). Obviously, there must be sufficient investment in the infrastructure, personnel, and processes that enable data management, archiving and release under a pragmatic, simplified, streamlined ethics review.

Sustainability

Long-term sustainability is a major challenge for biobanking. A number of considerations are critical to keeping biobanks and the research they support active and dynamic. The need for long-term investments into biological resources is clearly evident when longitudinal data are needed. Prospective collections of data and samples from asymptomatic individuals will allow future identification of premorbid and subclinical periods of disease development and will identify prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers and drug targets.13, 33, 34 Treatment follow-up studies require sampling and data collection over many years before substantive analysis can be performed. As molecular approaches to health and translational medicine are still in nascent stages, the value of already collected data will continue to grow as new knowledge and methodologies are applied to biobanks. Thus, preservation of today's biobanks is critical for realising the science and medicine of tomorrow.

Most conventional grant mechanisms with limited periods of funding are not sufficient for such sustainability.18 Alternative approaches to providing long-term support, such as the NIH contract model that has supported the Framingham Study, a distinguished successful biobanking initiative (nota bene, since long before the term ‘biobanking' was coined), must be developed and expanded. It may well be that the answer will lie in the use of a combination of approaches that includes long-term commitments from public and governmental sources27 (eg, the Estonian Human Genes Act (§27)) for functions related to the collection, maintainance, and storage of samples and information,35 as well as support from private industry.36

Embedding biobanks in health-care systems would help ensure reliable long-term funding and establish biobanks as a key component of the public health infrastructure. Both the long-term scientific benefits to be accrued from biobanking, and the personal health-care-related benefits that individuals may gain from having objective health-related information stored in biobanks, suggest that at least some types of biobanks may become nested within the health-care system.37 Indeed this trend is already evident in many nations as reflected by the ever-growing number of national hubs associated with the BBMRI.38, 39 If we want to ensure that the environment is right to support such nesting, it is critical that biobank operators, biobanking scientists, and science funders work hand in hand with policy makers and health-care strategists at all levels to ensure that the development of governance systems and regulatory frameworks, mechanisms for quality management, and systems for data storage, transfer, and integration are all harmonized and aligned to meet current and future needs. If done properly, such a systematic integration may be the essential foundation for future contributions that biobanks can make to human health. Thus, the design of approaches for data sharing across the spectrum of biobanks should dovetail with national health information systems to ensure that these systems are capable of interfacing (in an appropriately controlled manner) with the IT systems that hold the bulk of the detailed information in biobanks.

Obviously, funding is conditional on the level of ongoing benefit produced. Thus it is critical that biobanks are evaluated on an ongoing basis using well-defined metrics.40 This implies the urgent need to develop more formalized systems to objectively assess the value of biobanks or biobank networks over time. No such monitoring system exists yet, though some ideas for measuring a ‘Bio-Resource Impact Factor' (BRIF) are being designed and piloted.41 It will be necessary to record simultaneously the impact of biobanks as infrastructures supporting research and the scientific and operational contributions made by the ‘biobank researchers' (principal investigators, managers, bioinformaticians so on). This will be assisted by the development of systems that track the history of biobank collections and their applications using digital IDs for biobanks and researchers, and by a growing emphasis on publishing infrastructure data, as well as discoveries made as a result of accessing them. This, in turn, requires continued improvements in the underlying controlled vocabularies, databases, search systems, and guidelines addressing the ethical, legal, and social issues related to biobanks. Best practices for evaluating biobanks should be established42 and routinely updated. Likewise, criteria should be established to terminate biobanks, which fail to meet the established requirements and metrics.7 In addition to quantitative metrics for assessing the utility of biobanks, it is essential to also consider the less tangible, qualitative impact biobanks may have in fostering scientific advances43, 44 The development and use of such metrics also serve another purpose that may affect sustainability needs: such metrics help to incentivize and justify the field by providing objective criteria for unambiguously qualifying scientific contributions by engaged investigators.

Conclusion

Biobanking has the potential to be the most powerful single platform for health innovation and knowledge generation, provided that it is adequately resourced and networked. Maximizing the use, productivity, and value of biobanks worldwide will depend on a transition of the way in which biobanking is perceived and conducted. Harmonization across biobanks is crucial in order to make investigations more robust, more targeted, and more economical. Building on fundamental principles that emphasize synergy of effort, openness, and resource sharing for the benefit of all, international biobanking efforts have already begun to lay the groundwork for such harmonization. To realize fully the major public health benefits from the current patchwork of biobanking efforts, a coordinated strategy is required that engages the diverse stakeholders and proceeds through consensus building. We have articulated a vision and outlined a number of strategies for building the scientific, social, and political framework for continued progress. The key considerations underpinning the successful implementation of a road map to develop biobanking globally for health are summarized in Table 2. Drawing from the experience of an impressive number of harmonization initiatives in the field, we propose working to establish an international biobanking infrastructure and community. The collective output of these efforts includes guidance for the design and management of biobanks, for the development of SOPs for sample handling within a Quality Management System, cataloging and comparing data, and for coordinating development of compatible bioinformatics and ethico-legal frameworks. In addition to fostering biobank interoperability, with regard to the collection and exchange of data and samples, it is critical to form strategic alliances between governmental bodies, funding agencies, public and private science enterprises, and other stakeholders. The foundations of modern biobanking science have been laid. The challenges we describe must be met, if we are to realize, mobilize, and sustain the promise of major individual and public health benefits through the application of biobanking to biomedical research.

Table 2. Summary of key considerations underpinning a roadmap in global biobanking for health.

| 1. | Foster biobank interoperability through the development and maintenance of enabling technologies, procedures, networks, and compatible ethico-legal frameworks. |

| 2. | Ensure optimal strategic development, access, and utilization of biobank infrastructures across all stakeholders. |

| 3. | Promote legal systems that enable international biobanking and the safely regulated sharing of specimens and data. |

| 4. | Support the recognition of the scientific contributions of biobankers. |

| 5. | Encourage the development of formal systems for the evaluation of the impact of biobanks. |

| 6. | Enhance understanding of biobanking by the media, the general public, policymakers, and health-care strategists. |

| 7. | Build trust and respect for both open communication and a shared commitment to advance science for the improvement of human health. |

| 8. | Develop sustainability through stable funding and the embedding of biobanks in health-care systems. |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through funds from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), ENGAGE Consortium, grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007-201413 to JRH and IBL; BioSHaRE-EU, grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2010-261433 to JRH, PB, AJB, and IBL; through funds from Biobank Norway – a national infrastructure for biobanks and biobank-related activity in Norway – funded by the Norwegian Research Council (NFR 197443/F50) to JRH and IBL. We thank the contribution of the Public Population Project in Genomics (P3G) and biobanking-related work from FP7 Grant Agreement number: 212111 (BBMRI) to KZ, and MY, and the Austrian Genome Programme GEN-AU to KZ. BMK acknowledges the Canada Research Chair in Law and Medicine; Genome Canada/Genome Quebec GJBvO gratefully acknowledges support by a grant from the Ministry of Education, through the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO for the establishment of BBMRI-NL, a consolidated Netherlands Biobanking infrastructure. JEL gratefully acknowledges support by The Swedish Research Council Grant agreement 829-2009-6285 for the BBMRI.SE project. AM was supported by EU RDF Centre of Excellence in Genomics; The Estonian Biobank at EGC University of Tartu is funded by Ministry of Social Affairs and Ministry of Education and Research and EU FP7 project OPENGENE. Other sources of support for this work are the Wellcome Trust 096599/2/11/Z to JK, The Medical Research Council (UDBN, COPDmap), IMI (U-biopred) and Technology Strategy Board (STRATUM, ACROPOLIS) to MY, and The Medical Research Council (COPDmap) EU FP7 and (GEN2PHEN (Grant # 200754) to AJB.

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Paris: OECD; 2001. Biological Resource Centres: Underpinning the Future of Life Sciences and Biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Kent A. Policy barriers in coherent population-based research. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:8. [Google Scholar]

- The Wellcome Trust . UK: Wellcome Trust; 2011. Sharing research data to improve public health: full joint statement by funders of health research. [Google Scholar]

- Fortier I, Doiron D, Burton P, Raina P. Invited commentary: consolidating data harmonization—how to obtain quality and applicability. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:261–264. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier I, Doiron D, Little J, et al. Is rigorous retrospective harmonization possible? Application of the DataSHaPER approach across 53 large studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1314–1328. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Fortier I, Legault D, Burton P. The Public Population Project in Genomics (P3G): a proof of concept. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:664–665. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris; 2009. OECD Guidelines on Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases. [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories (ISBER) 2012 Best Practices for Repositories. Collection, Storage, Retrieval, and Distribution of Biological Materials for Research. Biopreserv Biobank. 2012;10:79–161. doi: 10.1089/bio.2012.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute National Cancer Institute (NCI) Best Practices for Biospecimen Resources 2011(online) http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices/ 2011-NCIBestPractices.pdf .

- Guerin JS, Murray DW, McGrath MM, Yuille MA, McPartlin JM, Doran PP. Molecular Medicine Ireland Guidelines for Standardized Biobanking. Biopreservation and Biobanking. 2010;8:3–63. doi: 10.1089/bio.2010.8101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuille M, Illig T, Hveem K, et al. Laboratory Management of Samples in Biobanks: European Consensus Expert Group Report. Biopreservation and Biobanking. 2010;8:65–69. doi: 10.1089/bio.2010.8102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua G, Bosman F, Dassesse T, et al. The role of the pathologist in tissue banking: European Consensus Expert Group Report. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:449–454. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0887-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton PR, Hansell AL, Fortier I, et al. Size matters: just how big is BIG?: Quantifying realistic sample size requirements for human genome epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:263–273. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9362–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CC, Su Z, Donnelly P, Marchini J. Designing genome-wide association studies: sample size, power, imputation, and the choice of genotyping chip. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.bbmri.eu/index.php/ publications-a-reports Annex 16: Final Report from WP5. (accessed 17 May 2011).

- Schofield PN, Eppig J, Huala E, et al. Research funding. Sustaining the data and bioresource commons. Science. 2010;330:592–593. doi: 10.1126/science.1191506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Chadwick R. Human genetic research: emerging trends in ethics. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nrg1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick R, Berg K. Solidarity and equity: new ethical frameworks for genetic databases. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:318–321. doi: 10.1038/35066094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prainsack B, Buy A. Swindon, UK: ESP Colour Ltd.; 2011. Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Biobanks. [Google Scholar]

- Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) Ethics Committee Statement on human genomic databases, December 2002. J Int Bioethique. 2003;14:207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuille M, Dixon K, Platt A, et al. The UK DNA banking network: a ‘fair access' biobank. Cell Tissue Bank. 2010;11:241–251. doi: 10.1007/s10561-009-9150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Harris JR, Tasse AM, et al. Towards a data sharing Code of Conduct for international genomic research. Genome Med. 2011;3:46. doi: 10.1186/gm262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye J, Heeney C, Hawkins N, de VJ, Boddington P. Data sharing in genomics—re-shaping scientific practice. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nrg2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, Wallace SE, Masca N, et al. DataSHIELD: resolving a conflict in contemporary bioscience—performing a pooled analysis of individual-level data without sharing the data. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1372–1382. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers BM, Harris JR, Burton PR, et al. From genomic databases to translation: a call to action. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:515–516. doi: 10.1136/jme.2011.043042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A.International Biobanking Regulations: The Promise and the Pitfalls 2011. Cancer World (online) http://www.cancerworld.org/pdf/ 3827_pagina_22-29_cuttingedge.pdf .

- Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID 2011 http://about.orcid.org/ .

- Birney E, Hudson TJ, Green ED, et al. Prepublication data sharing. Nature. 2009;461:168–170. doi: 10.1038/461168a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP, Adami HO. Nested randomized trials in large cohorts and biobanks: studying the health effects of lifestyle factors. Epidemiology. 2008;19:75–82. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815be01c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coriell Institute for Medical Research: Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Coriell Cell repositories 2011.

- Poste G. Bring on the biomarkers. Nature. 2011;469:156–157. doi: 10.1038/469156a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegman PH, Morente MM, Betsou F, de BP, Geary P. Biobanking for better healthcare. Mol Oncol. 2008;2:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estonian Human Genes Research Act2000 , http://biochem118.stanford.edu/Papers/Genome%20Papers/ Estonian%20Genome%20Res%20Act.pdf .

- Lindpaintner K. Biomarkers: call on industry to share. Nature. 2011;470:175. doi: 10.1038/470175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh MJ, Demir I, Harris JR, Burton PR. Realizing the promise of population biobanks: a new model for translation. Hum Genet. 2011;130:333–345. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuille M, van Ommen GJ, Brechot C, et al. Biobanking for Europe. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:14–24. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbm050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI) Final Report2011 , http://www.bbmri.eu/index.php?option=com_content&view= article&id=99&Itemid=78 .

- Cambon-Thomsen A. Assessing the impact of biobanks. Nat Genet. 2003;34:25–26. doi: 10.1038/ng0503-25b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambon-Thomsen A, Thorisson GA, Mabile L, et al. The role of a Bioresource Research Impact Factor as an incentive to share human bioresources. Nat Genet. 2011;43:503–504. doi: 10.1038/ng.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaught JB, Caboux E, Hainaut P. International efforts to develop biospecimen best practices. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:912–915. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier I, Burton PR, Robson PJ, et al. Quality, quantity and harmony: the DataSHaPER approach to integrating data across bioclinical studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MD, Dickherber A, Compton CC. Before you analyze a human specimen, think quality, variability, and bias. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8–13. doi: 10.1021/ac1018974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]