Abstract

Objectives. We tested a series of self-help booklets designed to prevent postpartum smoking relapse.

Methods. We recruited 700 women in months 4 through 8 of pregnancy, who quit smoking for their pregnancy. We randomized the women to receive either (1) 10 Forever Free for Baby and Me (FFB) relapse prevention booklets, mailed until 8 months postpartum, or (2) 2 existing smoking cessation materials, as a usual care control (UCC). Assessments were completed at baseline and at 1, 8, and 12 months postpartum.

Results. We received baseline questionnaires from 504 women meeting inclusion criteria. We found a main effect for treatment at 8 months, with FFB yielding higher abstinence rates (69.6%) than UCC (58.5%). Treatment effect was moderated by annual household income and age. Among lower income women (< $30 000), treatment effects were found at 8 and 12 months postpartum, with respective abstinence rates of 72.2% and 72.1% for FFB and 53.6% and 50.5% for UCC. No effects were found for higher income women.

Conclusions. Self-help booklets appeared to be efficacious and offered a low-cost modality for providing relapse-prevention assistance to low-income pregnant and postpartum women.

Tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of premature morbidity and mortality, and smoking cessation is associated with immediate and long-term improvement in quality of life and a wide range of health outcomes.1 Pregnant women represent a unique subgroup for whom continued smoking is associated with multiple immediate adverse outcomes, including increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and perinatal mortality.2 Pregnant women who smoke exhibit a relatively high rate of spontaneous smoking cessation. Today, nearly 50% of female smokers report quitting during pregnancy,3 and the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy dropped from 18.4% in 1990 to 10.4% by 2007.4,5 Moreover, interventions designed to promote smoking cessation during pregnancy have demonstrated efficacy.6

Unfortunately, smoking relapse rates following childbirth remain very high. Estimates range from 50% to 80% over the first year,7–9 and have shown little decline in recent years.3 Postpartum relapse is detrimental not only to the mother, but to the infant (and any other member of the household) who is exposed to secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke is associated with a variety of health problems in children, including decreased lung growth, increased rates of respiratory tract infections, otitis media, childhood asthma, sudden infant death syndrome, behavioral problems, neurocognitive decrements, and increased rates of adolescent smoking.10 It has been estimated that secondhand smoke is responsible for nearly 6000 deaths annually among children younger than 5 years.11

Numerous interventions have attempted to reduce postpartum smoking relapse, ranging from brief interventions during maternity hospitalization to intensive face-to-face counseling. However, recent meta-analyses concluded that postpartum relapse prevention has been ineffective.12,13 Thus, development and validation of effective interventions for preventing smoking relapse among pregnant and postpartum women remains a public health priority.

The general problem of smoking relapse led to the development of relapse-prevention interventions designed to facilitate long-term tobacco abstinence and circumvent the progression from an initial slip or lapse to a complete return to regular smoking. These interventions have largely taken the form of cognitive-behavioral therapies delivered in conjunction with initial smoking cessation counseling.14 However, less than 10% of smokers attempting to quit enroll in counseling programs, with the majority attempting cessation with minimal assistance.15 This observation led to the development of a minimal “self-help” relapse-prevention intervention designed to communicate key elements of cognitive-behavioral counseling in a format and engaging modality that is more amenable to dissemination and implementation—a series of 8 booklets delivered by mail.

These relapse-prevention booklets, currently titled Forever Free, include didactic information about the nature of tobacco dependence, instruction in the use of cognitive and behavioral coping skills to deal with urges to smoke, awareness of and preparation for high-risk “triggers” to smoke, strategies for managing an initial slip or lapse, and specific information and advice about weight control, stress, and health benefits associated with quitting smoking. The booklets were tested in 2 randomized controlled trials, with findings that they significantly reduced smoking relapse among recent quitters through at least 2 years after booklet delivery.16,17 Moreover, the intervention was highly cost-effective, with estimates as low as $83 per quality-adjusted life-year saved.17,18 A recent meta-analysis concluded that written self-help materials were the only type of relapse-prevention intervention for unaided quitters with established efficacy.12 Another meta-analysis concluded that self-help was more effective than standard care at producing initial smoking cessation among pregnant women,19 but self-help had not yet been tested for preventing postpartum relapse.

Smoking has increasingly become a behavior of lower socioeconomic groups, with the highest prevalence found among those with the least education and income. For example, in 2009, the smoking prevalence among those below the poverty line was 31.1% compared with 19.4% for those above the poverty line.20 Additionally, lower income and financial strain are associated with poorer success rates among those attempting to quit smoking.21,22 Aside from the emotional burdens of financial stress, low-income smokers may be hampered in their quitting attempts because of the practical limitations (e.g., cost and transportation) of finding and attending smoking cessation programs or obtaining cessation medications, as well as by the multiple barriers that impede clinicians from providing smoking cessation services to disadvantaged populations.23 In short, having less money and fewer resources places a significant burden on the smoker who wants to quit.

The association between income and smoking behavior extends to pregnant and postpartum women. For example, women with annual incomes less than $15 000 were found to be half as likely to quit smoking during their pregnancy (33% vs 67%), and among those who did quit, low-income women were nearly twice as likely to relapse within 4 months of delivery (63% vs 38%) compared with those with incomes of more than $15 000.3 Therefore, a low-cost, easily disseminated intervention, such as self-help booklets, might be particularly feasible for overcoming income-related barriers in this population.

The primary aim of the present study was to test, via a randomized controlled trial, a self-help intervention for preventing smoking relapse among a vulnerable population of smokers at uniquely high risk of relapse—pregnant and postpartum women. We modified the Forever Free series of self-help relapse-prevention booklets for use with pregnant women based on previous research and a systematic formative evaluation.24 We tested the hypothesis that women who received the series of Forever Free for Baby and Me booklets (FFB) would demonstrate less relapse through the course of the intervention (8 months postpartum) and beyond (12 months postpartum), compared with women who received high-quality existing materials that were less comprehensive.

In addition, we examined whether intervention efficacy was moderated by the key demographic, smoking, and pregnancy variables listed in Table 1 to identify highly responsive subgroups for future targeting. We did not specify a priori hypotheses with respect to these potential moderating variables.

TABLE 1—

Demographic, Pregnancy, and Smoking Variables as Reported at Baseline, by Intervention Group: Self-Help Booklets for Preventing Postpartum Smoking Relapse, United States, 2004–2008

| Demographic Variablesa | Forever Free Booklets (n = 245), %, Median, or Mean (SD) | Usual Care (n = 259), %, Median, or Mean (SD) |

| Race/ethnicity, | ||

| White | 93.9 | 90.7 |

| Black | 3.7 | 5.0 |

| Other | 2.4 | 4.2 |

| Hispanic | 5.8 | 5.7 |

| Education | ||

| < HS diploma | 9.4 | 8.9 |

| HS diploma or GED | 36.3 | 34.0 |

| College or technical school | 54.3 | 57.1 |

| Living with husband or boyfriend | 82.9 | 78.5 |

| Employed | 41.2 | 41.7 |

| Household income, $ | 30 000–40 000 | 30 000–40 000 |

| Age, y | 26.2 (5.7) | 25.4 (5.4) |

| Pregnancy | ||

| No. of pregnancies | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.6) |

| Had previous miscarriage(s) | 27.3 | 25.1 |

| Quit smoking before end of 1st trimester | 85.2 | 88.8 |

| Smoking | ||

| Years of smoking | 8.7 (4.8) | 8.5 (4.8) |

| Cigarettes/d | 15.0 (6.3) | 15.4 (6.9) |

| Precessation FTND score | 3.6 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.2) |

| Plan to quit for good | 64.5 | 68.7 |

| Other smoker(s) in house | 53.1 | 54.1 |

Note. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; GED = general equivalency diploma; HS = high school.

There were no significant group differences.

METHODS

Pregnant women who quit smoking were randomly assigned to 2 intervention arms: FFB or usual care control (UCC). The FFB intervention continued through 8 months postpartum, with outcome assessments at 1, 8, and 12 months postpartum.

We purchased the telephone numbers of 41 377 purportedly pregnant women from direct marketing companies. Information provided by the companies indicated that the phone numbers were compiled from Lamaze classes, baby registries, mail order purchases, magazine subscriptions, and questionnaire data. We made up to 3 attempts for each number. Each pregnant woman was screened for inclusion criteria: at least 18 years old; able to speak and read English; currently in months 4 through 8 of pregnancy; previously smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year before pregnancy; quit smoking either in anticipation of, or during pregnancy; and had abstained for the past week. Of 7943 women reached by phone, 731 met criteria and were invited to enter the study, which involved receiving information about maintaining tobacco abstinence and completing several questionnaires by mail. Of the eligible women, 700 agreed to participate and provided verbal informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization.

Interventions

Participants were assigned to the 2 intervention arms by a computer algorithm using simple randomization at the time of data entry of the telephone screening questionnaire.

Usual care control.

Participants received a copy of the National Cancer Institute Booklet, Clearing the Air,25 and the American Cancer Society pamphlet Living Smoke-free for You and Your Baby.26 The former is a 36-page, comprehensive guide toward quitting smoking, with 7 pages dedicated to relapse prevention. However, the content is not customized for pregnant or postpartum women. The latter is a trifold pamphlet that describes the benefits of quitting smoking during pregnancy and staying quit after the baby is born. Thus, women in the UCC condition received 2 high-quality publications.

Forever Free Booklets.

Participants received the series of FFBs. Based on our formative evaluation24 and the existing research literature, we modified the original FFBs in 2 ways: the examples, vignettes, and graphics were customized to pregnancy, and there was greater emphasis on social support and pregnancy-specific stressors. The pregnancy series was enhanced by the addition of 2 new booklets: A Time of Change was delivered shortly before a participant’s due date, and Partner Support was designed to be shared with the participant’s partner. The sequence and timing of the booklet distribution was based on our formative work and goal to provide timely content over the pregnancy and postpartum period. The first 4 booklets (Overview; Smoking Urges; Smoking and Health; A Time of Change) were mailed over equal intervals between the date of a participant’s enrollment in the study and her expected due date. The next 5 booklets (What If You Have a Cigarette?; Smoking, Stress and Mood; Lifestyle Balance; Smoking and Weight; Life Without Cigarettes) were mailed at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 months postpartum. Partner Support was mailed with the first booklet, including instructions to deliver it to the participant’s primary partner. Booklets were 7 × 10 inches and ranged from 9 to 21 pages in length, with a mean of 15 pages. They were written at the fifth to sixth grade reading level.

Assessments

To encourage compliance, the number and length of assessments were kept to a minimum. Brief assessment questionnaires were mailed to participants at baseline and the 3 follow-up points (1, 8, and 12 months postpartum). As an incentive, participants were paid $20 for completing the baseline questionnaire, and $25, $30, and $35 for completing the 3 follow-up questionnaires.

Baseline assessment.

This short questionnaire included demographic and smoking history items, including a retrospective version of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.27 In addition, we assessed several psychological variables for secondary analyses, including measures of depression and social support. We also collected contact information for 2 other individuals to aid us in locating the participant, if necessary.

Follow-up assessments.

Participants were sent follow-up assessments at 3 points: (1) 1 month after their anticipated delivery date, (2) 8 months postpartum, corresponding to the end of the intervention, and (3) 12 months postpartum. Assessments included use of tobacco and other smoking cessation aids since the previous contact, the psychological measures, and participants’ use and evaluation of the intervention materials they received, including a modified Client Satisfaction Questionnaire.28 The primary outcome variable was 7-day point-prevalence abstinence, which requires 1 week of reported complete tobacco abstinence at the time of follow-up. This variable allows for recovery from a temporary lapse, or even a new cessation attempt following a relapse. Because relapse-prevention interventions encourage such actions, it is a more appropriate outcome measure than alternatives, such as continuous abstinence.

Biochemical verification.

Because participants were recruited from throughout the United States, and assessments were conducted by mail, bioverification of smoking status was not feasible. Instead, we conducted face-to-face interviews and collected breath carbon monoxide (CO) and saliva (for cotinine analysis) on participants who lived within 100 miles of our laboratory, and who reported abstinence at any of the 3 follow-up points. The breath sample was collected with a portable CO monitor (Micro CO, Micro Direct, Inc., Lewiston, Maine), and the saliva sample was collected in a 2-milliliter tube for immediate cotinine analysis using the NicAlert dipstick (Nymox, Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey). Cutoffs of 8 parts per million for CO and 10 nanograms per milliliter for cotinine were used.29 Participants were paid $35 for the interview and biosamples. Of 22 participants tested, 21 (95%) provided biosamples that were consistent with their self-reported abstinence, lending confidence to the accuracy of self-report in this study.

Statistical Overview

Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) using an autoregressive working correlation structure assessed treatment effects on smoking status across the 3 follow-up points. Bivariate logistic regression was used to test treatment effects at each follow-up point. Potential moderators were tested individually. The demographic, pregnancy, or smoking variable (Table 1) was entered into a GEE model with treatment condition.

Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data, which ranged from 8.3% to 10.4%, using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method.30 The multiple imputation incorporated 46 variables: (1) smoking status at each follow-up, (2) the predictors for the models being tested (i.e., treatment and potential moderator), and (3) numerous auxiliary variables that were significantly related to smoking status (e.g., whether there was another smoker in the house, confidence about future abstinence, anxiety or depression). Ten imputed data sets were generated using PROC MI in SAS/STAT software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

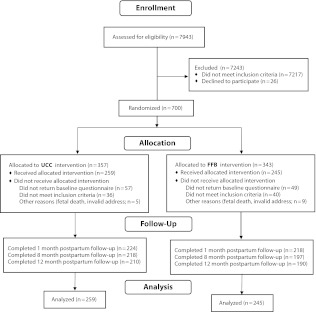

The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Recruitment occurred between April 2004 and April 2007. Of 700 women who consented and were randomized, 594 (85%) returned baseline questionnaires, and 504 (85%) remained eligible based primarily on inclusion criteria reassessed on the baseline questionnaire, constituting the final sample for the study. Follow-up assessments were conducted through August 2008. Return rates were 88%, 82%, and 79% for the 3 follow-ups, respectively, and they did not differ statistically between groups.

FIGURE 1—

CONSORT flow diagram: Self-Help Booklets for Preventing Postpartum Smoking Relapse, 2004–2008

Note. FFB = Forever Free for Baby and Me booklets; UCC = usual care control.

Key participant characteristics as reported at baseline are listed in Table 1. No significant treatment group differences emerged on any of these variables.

The GEE analysis revealed a marginally significant interaction (P = .096) between treatment and follow-up. The top section of Table 2 displays abstinent rates by treatment condition for all participants. Bivariate logistic regression at each follow-up revealed a significant group difference only at 8 months postpartum.

TABLE 2—

Bivariate Logistic Regression Models of Postpartum Smoking Status for All Participants and by Household Income and Age Groups: Self-Help Booklets for Preventing Postpartum Smoking Relapse, United States, 2004–2008

| Percent Abstinent |

||||

| Follow-Up Point | Forever Free Booklets | Usual Care | P | OR (95% CI) |

| All participants | ||||

| 1 mo postpartum | 74.8 | 75.3 | .891 | 0.99 (0.80, 1.22) |

| 8 mo postpartum | 69.6 | 58.5 | .02 | 1.27 (1.04, 1.56) |

| 12 mo postpartum | 66.2 | 58.6 | .104 | 1.18 (0.97, 1.43) |

| Household income ≤ $30 000 | ||||

| 1 mo postpartum | 72.3 | 71.1 | .885 | 1.02 (0.75, 1.40) |

| 8 mo postpartum | 72.2 | 53.6 | .012 | 1.48 (1.09, 2.00) |

| 12 mo postpartum | 72.1 | 50.5 | .003 | 1.58 (1.17, 2.14) |

| Household income > $30 000 | ||||

| 1 mo postpartum | 77.5 | 787.7 | .753 | 0.96 (1.16, 0.72) |

| 8 mo postpartum | 68.5 | 63.1 | .42 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.47) |

| 12 mo postpartum | 62.5 | 64.6 | .689 | 0.95 (0.75, 1.21) |

| Ages 18–24 y | ||||

| 1 mo postpartum | 73.2 | 72.2 | .874 | 1.02 (0.75, 1.40) |

| 8 mo postpartum | 75.4 | 56.2 | .005 | 1.55 (1.15, 2.09) |

| 12 mo postpartum | 68.9 | 50.4 | .007 | 1.47 (1.11, 1.95) |

| Ages 25–50 y | ||||

| 1 mo postpartum | 76.3 | 78.9 | .619 | 0.93 (0.69, 1.25) |

| 8 mo postpartum | 66.7 | 63.1 | .577 | 1.08 (0.82, 1.44) |

| 12 mo postpartum | 63.8 | 68.3 | .475 | 0.90 (0.68, 1.19) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Of the variables listed in Table 1, only annual household income and age were found to be moderators of the treatment effect. Income was analyzed following a median split with a cutpoint of $30 000. The GEE analysis revealed a 3-way interaction between treatment, follow-up, and income (P = .044). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, no treatment effects were found among higher income participants. However, the FFB treatment produced significantly and substantially greater abstinence rates at both 8 and 12 months among lower income women.

FIGURE 2—

Treatment effects as a function of annual household income (a) ≤ $30 000 and (b) > $30 000: Self-Help Booklets for Preventing Postpartum Smoking Relapse, 2004–2008.

The interaction of treatment, follow-up, and age (median split at 24) was marginally significant (P = .098). As shown in Table 2, the results for younger and older participants closely paralleled those of lower and higher income participants. This was not surprising, given that age covaried with income (P < .001), with 66% of the lower income women being younger than 25 years.

Given the observed interactions between treatment and income, participants’ satisfaction (responders only) was analyzed via 2-factor (treatment, income) analyses of variance. The FFB participants reported greater satisfaction with the materials at all follow-ups (P < .001). Additionally, lower income participants reported greater satisfaction at 12 months than did higher income participants (P = .004). The degree to which participants’ perceived the information presented in the materials to be new to them was assessed at 1 and 8 months. At both follow-ups, there were main effects for treatment (P ≤ .04) and income (P < .001), with FFB and lower income participants reporting greater novelty of the information.

To calculate the expected cost per user of the FFB intervention in 2011, we included current printing and delivery cost of the booklets themselves ($8.00); labor costs associated with enrolling and tracking users, and mailing the booklets, weighted by the hourly wage rate of correspondence clerks in the United States ($16.72); postage ($14.80); and other supplies and overhead ($14.08). These estimated expenses summed to a total of $53.60 per user. Based on the differential abstinence rate of 21.6% points, compared with UCC, we calculated that the cost of producing each additional abstinence at 12 months postpartum for low-income women to be $248.

DISCUSSION

Postpartum smoking relapse has been a persistent problem in public health. This randomized controlled trial compared the mailing of 10 self-help booklets designed for pregnant and postpartum women against “usual care,” consisting of existing materials. For the sample as a whole, we found that the FFBs produced a differential abstinence of 11% compared with UCC at 8 months postpartum, but statistical significance was not maintained through 12 months. However, the intervention effects were moderated by household income, such that among low-income women (household income < $30 000), the FFB condition produced differential abstinence of 19% at 8 months and 22% at 12 months. By contrast, no significant intervention effects were found among higher income women. Similarly, younger women benefited from the FFB intervention.

The full-sample treatment effect at 8 months of a minimal, self-help intervention compared well against the best outcomes in the literature, which were found with much more intensive interventions.12,13,31 It was noteworthy, however, that significant differences did not persist beyond 8 months postpartum, when the final booklet was mailed. Other, more intensive relapse-prevention interventions also showed medium-term efficacy that failed to be maintained through the first postpartum year.32,33 Nevertheless, our findings suggested the possibility that extending the duration of the intervention might extend its efficacy.

This comparison might have underestimated the full advantage of FFB over purely standard care. We generously labeled our control condition “usual care” because, beyond whatever assistance they had already received from their own health care providers, participants also received high quality, preexisting, self-help materials. The actual comparison was between 2 minimal interventions delivered by mail—one more targeted and comprehensive than the other.

The major finding from this study was the large effect of the FFB intervention among women from low-income households, increasing the odds of maintaining abstinence by approximately 50%. Similar effects were found for women younger than 25 years, but we focused on income rather than age because of the more direct public health implications. We did not have a priori predictions regarding potential moderating variables, so replication of these post hoc findings will be necessary. Previous research showed that women of low socioeconomic status are more likely to smoke during pregnancy and, if they do quit, to relapse after delivery.3 This pattern was observed in this study among women in the UCC arm. However, receiving the FFB intervention essentially negated the disadvantage of low income with respect to postpartum relapse. Among these low-income women, the abstinence rate remained stable through 12 months postpartum.

Why were the FFBs so much more effective among low-income women? First, it should be noted that the materials were developed to be accessible to a diverse population, with respect to its content, reading level, and graphic design. Second, the intervention was delivered entirely by mail, a modality that could overcome many of the barriers associated with the provision of preventive health care, including cost and transportation limitations. Therefore, these booklets might represent a substantial improvement over the usual care received by lower income women in terms of smoking cessation and relapse prevention during and after pregnancy. By contrast, higher income women might already be educated about these issues and received assistance and support from professionals and family members. This conjecture was supported by the finding that lower income women rated the materials more favorably and as containing more novel information compared with higher income women, and that the FFBs were rated higher in these categories than the usual care booklets.

Limitations

Three primary limitations of this study should be noted. The first, as mentioned previously, was that a strong treatment effect was found only in the subgroup of women from low-income households—a post hoc finding that requires replication.

The second limitation involved generalizibility. Although we used a prospectively recruited sample, it was not population-based. Therefore, it was not necessarily representative of the full population of pregnant ex-smokers. Most notably, the sample obtained from direct marketers underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities.

Finally, smoking status was determined by self-report with bioverification for only a small subsample because the study was conducted by mail, with women recruited from throughout the United States. Studies that compared self-report to biochemical analyses found inconsistent biochemical results from 2% to 30% of self-reported abstainers.34–36 We found inconsistent biochemical results in approximately 5% of our tested subsample. Therefore, our reported abstinence rates might be somewhat inflated. Indeed, the overall UCC relapse rate of 41% was lower than that typically reported.7–9 However, whereas biochemical verification tends to reduce overall abstinence rates, it does not alter observed treatment differences.29,37

Conclusions

Results of this study indicated that a minimal, inexpensive, self-help intervention that was previously shown to reduce smoking relapse in a general population of smokers could be adapted for pregnant women—a particularly challenging subpopulation of smokers. The FFBs produced substantial effects among lower income and younger women through 12 months postpartum. These findings further demonstrated that written self-help materials, which can be easily disseminated, could be at least as effective for preventing smoking relapse as much more intensive and costly face-to-face or telephone-based interventions, and might have a potential role in reducing socioeconomic health disparities. Future effectiveness research is needed to confirm the booklets’ impact among low-income women, particularly when disseminated in a more naturalistic manner, such as via public health clinics.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Cancer Institute (grant R01 CA94256).

The authors wish to thank the following researchers for their contributions to the study: Terrance Albright, PhD, Nannette Roach, PhD, Thomas Chirikos, PhD, Gang Han, PhD, Erika Litvin, PhD, Kirsten Phillips, PhD, Laura Cardona, Haley Courville, Sharon DeJoy, Ellen Koltz, Jennifer Pedraza, and Kristen Sismilich.

Copies of the Forever Free for Baby and Me booklets (in English and Spanish) can be found on the National Cancer Institute Web site http://www.smokefree.gov. Rights to the booklets are owned by Moffitt Cancer Center and any revenue generated by them may be shared with the authors.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was granted by the University of South Florida.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1990. DHHS Publication No (CDC) 90–8416.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-12):1–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000-2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(4):1–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking during pregnancy–United States, 1990-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(39):911–915 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau Women’s Health USA 2010. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colman G, Grossman M, Joyce T. The effect of cigarette excise taxes on smoking before, during and after pregnancy. J Health Econ. 2003;22(6):1053–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(5):541–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4, suppl):1007–1015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aligne CA, Stoddard JJ. Tobacco and children. An economic evaluation of the medical effects of parental smoking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(7):648–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agboola S, McNeill A, Coleman T, Leonardi Bee J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1362–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajek P, Stead LF, West R, Jarvis M, Lancaster T. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD003999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, Litvin EB. Relapse and relapse prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:257–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandon TH, Collins BN, Juliano LM, Lazev AB. Preventing relapse among former smokers: a comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandon TH, Meade CD, Herzog TA, Chirikos TN, Webb MS, Cantor AB. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: dismantling the effects of amount of content versus contact. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):797–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chirikos TN, Herzog TA, Meade CD, Webb MS, Brandon TH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a complementary health intervention: the case of smoking relapse prevention. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naughton F, Prevost AT, Sutton S. Self-help smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(4):566–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >or=18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135–1140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Costello TJet al. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):702–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumenthal DS. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation services reported by clinicians in underserved communities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn G, Ellison BB, Meade Cet al. Adapting smoking relapse-prevention materials for pregnant and postpartum women: formative research. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(3):235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute Clearing the Air: Quit Smoking Today. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2003. NIH Publication No. 03–1647 [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Cancer Society Living Smoke-free for You and Your Baby. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MSet al. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among diverse low-income women: a randomized clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(4):326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nurs Res. 2000;49(1):44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Dahinten S, Hall W. Twelve-month follow-up of a smoking relapse prevention intervention for postpartum women. Addict Behav. 2000;25(1):81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd NR, Windsor RA, Perkins LL, Lowe JB. Quality of measurement of smoking status by self-report and saliva cotinine among pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 1998;2(2):77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJet al. Biochemical verification of smoking status in pregnant and recently postpartum women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(1):58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klebanoff MA, Levine RJ, Morris CDet al. Accuracy of self-reported cigarette smoking among pregnant women in the 1990s. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(2):140–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasgow RE, Mullooly JP, Vogt TMet al. Biochemical validation of smoking status: pros, cons, and data from four low-intensity intervention trials. Addict Behav. 1993;18(5):511–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]