Abstract

Electronic health records (EHRs) have great potential to serve as a catalyst for more effective coordination between public health departments and primary care providers (PCP) in maintaining healthy communities.

As a system for documenting patient health data, EHRs can be harnessed to improve public health surveillance for communicable and chronic illnesses. EHRs facilitate clinical alerts informed by public health goals that guide primary care physicians in real time in their diagnosis and treatment of patients.

As health departments reassess their public health agendas, the use of EHRs to facilitate this agenda in primary care settings should be considered. PCPs and EHR vendors, in turn, will need to configure their EHR systems and practice workflows to align with public health priorities as these agendas include increased involvement of primary care providers in addressing public health concerns.

Electronic health records (EHRs) have great potential to serve as a catalyst for more effective coordination between public health departments and primary care providers in maintaining healthy communities. As prominent health risks to the community continue their shift from contagious diseases to chronic illnesses, public health departments are increasingly focused on conditions such as diabetes and obesity. At the same time, serious threats persist from traditional public health concerns, such as communicable disease outbreaks.

Primary care providers, and particularly community health centers (CHCs), that provide care for low-income populations are on the front lines in treating and containing both communicable diseases and chronic illnesses that are more prevalent in these communities. Traditional models of primary care are also evolving, with increased focus on community-based approaches in response to changing financial incentives and formal recognition programs, such as the Patient-Centered Medical Home certification offered by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Joint Commission.1,2 Use of these models is facilitated by the parallel increase in adoption of EHRs.

Federal incentive programs have been a proponent of EHR implementation and “meaningful use” of EHRs among primary care providers, with targeted funding to support their adoption among CHCs.3 The promotion of health information technology to improve the public’s health is 1 of 5 focus areas for meaningful use of EHRs. Finally, 1 of the 3-part aims of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMMS) is the improvement of population health—a goal that will only be met through improved coordination of primary care and public health.4,5

In 2003, the potential for addressing community health needs with the aid of EHR data exchange initiated a partnership between The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) and The Institute for Family Health. Together, these organizations have developed, tested, implemented, and monitored the use of an EHR in meeting public health and primary care goals. NYC DOHMH is one of the world’s largest public health agencies, operating programs in disease control, environmental health, epidemiology, health care access, health promotion and disease prevention, and mental hygiene. It also makes public health-enabled EHRs available to over 2500 primary care providers throughout New York City as part of its Primary Care Information Project (PCIP).

The Institute for Family Health is a nonprofit organization that provides care to more than 80 000 patients in 26 federally qualified health center sites in New York City and New York State’s Mid-Hudson Valley. The Institute’s goal in establishing an EHR system was not only to enhance the quality of patient care in its own practices, but also to improve the health of the communities it serves. Recognizing that the 2 organizations had parallel missions to maintain healthy communities, the Institute and NYC DOHMH partnered in EHR data exchange initiatives to meet the shared goals of improving the surveillance and management of both communicable disease and chronic disease. Projects addressing these goals are described below.

IMPROVE SURVEILLANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF COMMUNICABLE DISEASE

Syndromic surveillance, the practice of monitoring encounters for symptoms that may represent infectious diseases and other conditions of public health concern, can be facilitated by EHRs through automated data reporting to public health departments. The Institute for Family Health partnered with NYC DOHMH to become one of the first ambulatory settings to participate in syndromic surveillance.6 Routinely collected chief complaint information along with important demographic data from Institute patients are de-identified and transmitted to NYC DOHMH daily through a secure encrypted data transfer mechanism. Respiratory illness, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting are the key symptoms monitored, with analysis to determine when the incidence of these syndromes exceeds expected thresholds.

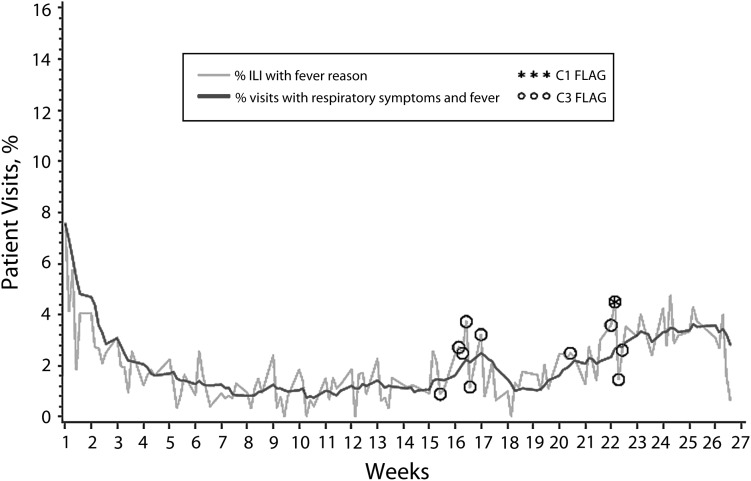

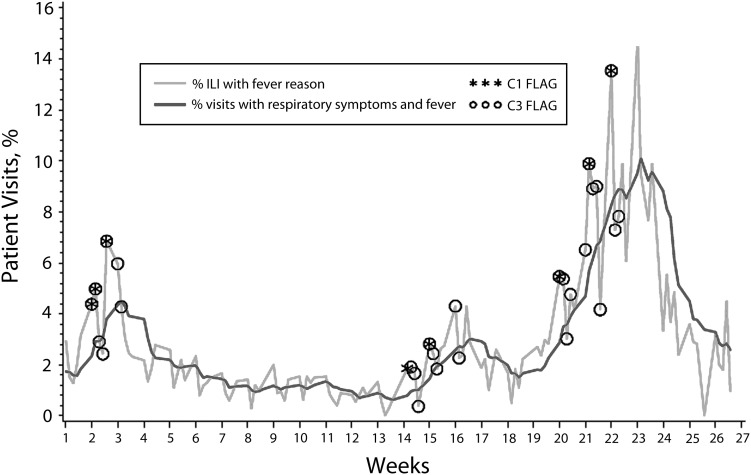

Figures 1 and 2 present the percentage of patient visits on a daily and rolling weekly basis in which influenza-like illness (ILI) was the documented reason for visit at all of the Institute’s care sites in New York City and the Mid-Hudson Valley (Upstate), respectively, during the H1N1 epidemic. These data illustrate that the peak in ILI visits at Upstate sites lagged the peak experienced in New York City sites by 5 months, which guided the Institute to redistribute immunization resources well after the New York City peak. The ability to conduct this type of disease monitoring in real time has the potential to inform primary care providers and public health departments of shifting needs during outbreaks. As increasing numbers of health care providers implement public health–enabled EHRs, public health departments have the potential to receive syndromic surveillance data that present a more comprehensive profile of the population.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of patient visits at New York City sites for influenza-like illness (ILI): Institute for Family Health, June 8–December 4, 2009.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of patient visits at New York State’s Mid-Hudson Valley sites for influenza-like illness (ILI): Institute for Family Health, June 8–December 4, 2009.

Like many public health departments, NYC DOHMH monitors the incidence of disease through registries and required reporting of notifiable conditions, such as tuberculosis, by health care providers. Despite legal mandates in most states, reporting rates for these conditions are not optimal.7,8 The Institute facilitated public health reporting by creating alerts within its EHR that remind providers at the point of care that a particular diagnosis is reportable and provide a link to the reporting form. Patient demographics are automatically populated in the form to minimize providers’ time and effort in submitting reports.

Institute data on immunization and lead screening, which must be submitted to the city’s public health registries, are automatically uploaded from the Institute’s EHR system to NYC DOHMH, eliminating the need for providers or staff to submit reports. Primary care providers can use registry data to look up immunization histories for patients in their practices, potentially reducing both gaps and duplication in immunization schedules.

Findings from epidemiological investigation by public health agencies can inform primary care practices. This information triggers message distribution through channels such as the Health Alert Network in which nearly all large public health entities participate, and that may be delivered to the point of care through EHRs.9,10 The Institute and NYC DOHMH have tested and implemented point-of-care public health alerts for a variety of conditions. For example, New York City has issued messages about West Nile Virus detection through its Health Alert Network, which Institute staff programmed as alerts for their primary care providers, prompting them to consider this condition for patients presenting with fever and headache. In another example, a NYC DOHMH alert about increased cases of Legionella in a Bronx neighborhood prompted the Institute to create an alert to local providers to consider this condition in patients with respiratory symptoms. An order set attached to the alert facilitated urine antigen testing that would otherwise have been unlikely. Such alerts can prompt primary care providers to take timely action to appropriately treat patients for emerging conditions.

Primary care providers can also be encouraged to take an active role in disease surveillance efforts. During a measles outbreak, Institute providers treating patients with rash and fever responded to programmed prompts and collected specimens requested by NYC DOHMH at the time patients presented to the clinic. At the onset of the H1N1 epidemic in 2009, clinical alerts requested that providers at Institute sites collect viral specimens for a pilot surveillance project to determine the viral etiologies to respiratory illness in the community.11 Because of the success of this alert, the Institute has continued to provide community level samples for detecting ILI.

IMPROVE SURVEILLANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC DISEASE

Public health departments will need new tools and partners to address the growing epidemic of chronic disease. The functionality of EHRs can be expanded to empower CHCs and other clinicians to provide better preventive and acute care through clinical decision supports.12,13 Still, primary care providers are challenged to incorporate dozens of care guidelines into practice. The finite resources available across the health care system make it critically important to have a public health agenda that prioritizes services that have the greatest impact on health.1,14,15

Recognizing this need, NYC DOHMH launched the Take Care New York (TCNY) initiative in 2004.16 TCNY set an ambitious agenda to prioritize actions to help New York City improve health in 10 key areas, each of which causes significant illness and death but is amenable to intervention. NYC DOHMH established population-level targets for each of these priority areas, which include 10 goals for all New Yorkers:

Have a regular doctor or other health care provider.

Be tobacco-free.

Keep your heart healthy.

Know your HIV status.

Get help for depression.

Live free of alcohol and drugs.

Get checked for cancer.

Get the immunizations that you need.

Make your home safe and healthy.

Have a healthy baby.

To integrate the TCNY agenda into its primary care efforts, the Institute collaborated with NYC DOHMH in developing a model clinical-decision support system at its practice sites that is organized around these goals. Health department and Institute staff reviewed each goal in the context of medical evidence and practice guidelines. A logic model was created for each goal that incorporated available EHR data and workflows, and also assessed feasibility and acceptability in practice. More than 40 alerts addressing TCNY goals are currently programmed into the Institute’s EHR. Mindful of issues such as “alert fatigue,”17 reminders were engineered to fit into clinical workflows and incorporated tools to facilitate adherence, such as drop-down order sets, documentation screens, links to patient education materials, and the option to suppress the alert if the recommendation was not indicated for the patient.

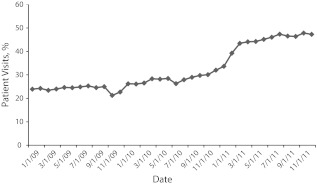

Health screening recommendations incorporated into many of the TCNY alerts often require care management and follow-up to improve health outcomes. As part of its health care quality program, the Institute has used EHR data to develop disease registries and reports that enable outreach workers and care managers to identify and contact patients who are overdue for a test, screening, or visit, or have a clinical measure that requires special attention. Another critical component of the TCNY partnership is a reporting system to monitor these measures at each practice site. A current report on all patients with documented HIV test results, corresponding to TCNY Goal 4, is presented in Figure 3. This example is illustrative of the need to couple automated alerts with a supportive health-care delivery system. Rates of HIV testing began improving markedly in 2011 as the Institute’s health centers began to incorporate on-site rapid testing, market related messages to patients, and redirect electronic alerts and order sets to nursing staff to encourage testing prior to the patient seeing the provider.

FIGURE 3—

Institute for Family Health office visits in which patients aged 18 years and older have documented HIV test result or self-reported HIV status: 2009–2011.

Alerts can also guide providers to public health resources to which they can refer patients. For example, the provider alert to address smoking, TCNY Goal 2, contains an embedded, prepopulated referral form for the Fax-to-Quit line operated by the New York State Department of Health. Other possibilities include referrals to free mammography and additional cancer screening programs operated by publicly funded or other programs. This functionality is particularly pertinent to CHCs that serve patients whose lack of insurance often creates barriers to health services. Public health programs should consider partnering with primary care providers to use EHRs to inform them of these types of community programs at the point of care.

EHR data can be used to identify primary care patients at risk for developing certain chronic diseases or the sequelae of existing chronic conditions. Research has demonstrated that the data typically stored in EHRs can be used to identify patients at high risk for certain diseases and that patient knowledge of increased risk of disease may motivate preventive behavior such as obtaining cancer screenings or vaccinations.18–20 The Institute has employed clinical data in the EHR to identify and reach out to patients at increased risk for disease, with initial projects focused on colon cancer screening and diabetes.

Another project uses patients’ demographic data to screen for Hepatitis B. Screening for Hepatitis B is not recommended for the general population; however, screening is indicated for immigrants from certain countries where prevalence is high.21,22 Using data on patients’ country of origin, which is part of an organizational initiative to collect patient data at the granular level, the Institute implemented an alert for Hepatitis B screening that prompts providers to order appropriate testing if the patient is from a country in which Hepatitis B is endemic but has not been tested or diagnosed with this condition. In the first 5 months after implementation, the alert “fired” 32 515 times and resulted in the ordering of 785 Hepatitis B surface antigen tests, with 10 previously unknown cases of Hepatitis B identified. Early identification of chronic infectious diseases in primary care practices can prevent adverse outcomes like cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Racial and ethnic disparities in health remain a persistent public health problem. Minimal progress in this area has been attributed, in part, to a lack of standardized demographic data in health care settings that can identify gaps and point toward best practices for eliminating disparities.23–26 Recent federal health care reform and health information technology legislation call for health care providers to collect data on patients’ race, ethnicity, and language as part of health system change, and lays the foundation for identifying and addressing health disparities throughout the health care system.3,27 EHRs can become powerful tools in these efforts when they enable health quality data to be monitored via patient demographics at the granular level.

The Institute has documented patients’ race, ethnicity, and preferred language for health care in its EHR system since its implementation in 2002, with a recent expansion of demographic data collection based on recommendations from The Institute of Medicine.28 These data enable the Institute to monitor care processes and outcomes for patients in particular racial and ethnic groups. Progress reports on TCNY measures are run by patient race and ethnicity, as are disease registries and other clinical reports. Disparities identified in the HbA1c levels of Institute patients with diabetes spurred the development of an enhanced diabetes-care model that incorporates outreach and care management for patients with clinical indicators outside of the recommended range, who are more likely to be of minority race or ethnicity. Documenting granular health data is the first step in identifying gaps in care for which both front line providers and public health agencies can then marshal resources to identify individuals and groups experiencing barriers to high-quality primary care and to target public health education campaigns.

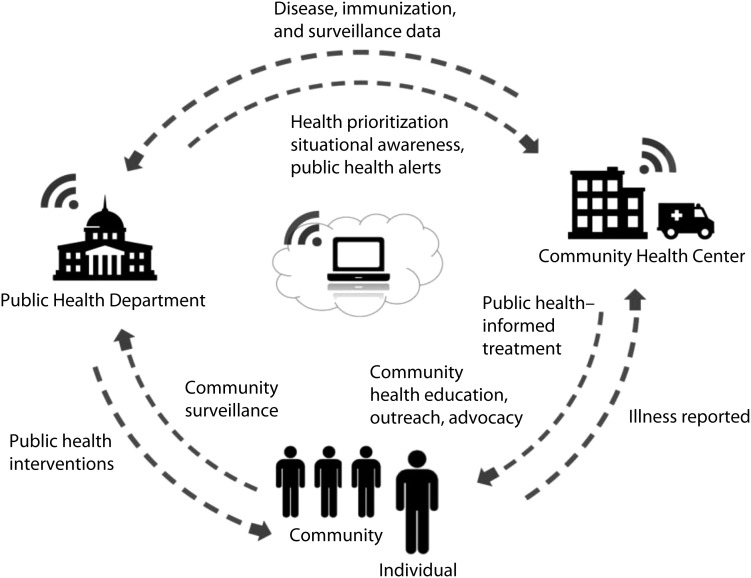

REVIEW

Multiple sources of health data can inform the priorities and actions of public health departments, primary care providers, individuals, and communities, when appropriately analyzed and coordinated. EHRs can form the hub of information exchange as primary care providers document illnesses that can be uploaded to public health departments to monitor disease and inform point-of-care decisions about treatment through provision of relevant public health information. Public health departments can use aggregated EHR data, along with other sources of data, to prioritize community interventions and public health messages, as well as recommendations for primary care screenings and treatment. Individuals and communities make daily decisions about their health and lifestyles that are reported to their primary care providers and to public health departments through community surveys and assessments. EHRs can help public health departments and primary care providers efficiently coordinate their priorities to ensure that patients and communities receive consistent, high-impact health messages. Data from one point on the hub can inform action on another point, forming a community health information ecosystem that fosters coordination of data and health promotion activities. Figure 4 diagrams the potential flow of information between stakeholders.

FIGURE 4—

Exchange of health data between public health, primary care, individuals, and communities.

Although the partners in the initiatives described herein were successful in integrating public health and primary care functionality, there are currently several challenges to expanding these collaborations more broadly. First, adoption of EHRs among primary care providers is growing yet limited. Roughly 25% of office-based physicians in the United States have a basic EHR system and another 10% have a fully functional EHR system.29 Furthermore, there are many EHR systems in existence today, and this variability can make it difficult for public health agencies to engage with multiple primary care partners and ensure that key communities are represented in health partnerships. Standards for the coding and transmission of public health data by EHRs are in development, but many such standards have yet to be developed and others have not been broadly adopted by the EHR vendor community and by public health departments. Limited resources constrain the ability of public health agencies and primary care providers to collaborate and innovate.

CONCLUSIONS

Public health departments and primary care providers must integrate their efforts in the development of electronic health records if the United States is going to successfully move from a health care system that is based on volume of services to that which is focused on maintaining healthy communities. Primary care providers, as “deputized public health officers,” have the ability to act as the eyes of the health department in the community. They are made more efficient and effective in this role when supported by public health–enabled electronic health records.

Primary care providers, particularly CHCs, rely on public health departments to provide the expert guidance and situational awareness that facilitates effective health care delivery. EHRs provide a mechanism for health departments to deliver such guidance in real time, as providers make care decisions. As public health departments develop new guidelines and priorities for improving population health, it will be important to consider how they can be facilitated by EHRs in primary care settings. Primary care providers and EHR vendors, in turn, will need to configure their EHR systems to align with public health priorities. In this time of rapid health information technology advancement and health care realignment, it is critical that public health departments and primary care providers jointly plan how to harness the power of EHRs and achieve the benefits of integration.

Acknowledgments

The projects described in this article were supported by several federal agencies, including The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant P01 HK000029), the Health Resources and Services Administration (grant H2LCS18144), and The Department of Homeland Security (grant 2009-OH-091-ES0001).

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of many colleagues at The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and The Institute for Family Health who have been integral to the successful collaboration of the 2 organizations, as well colleagues at the Columbia University Department of Biomedical Informatics who have provided and continue to provide expert guidance.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was received for projects described in the manuscript that involved human research subjects.

References

- 1.The National Committee for Quality Assurance. Patient-Centered Medical Home. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/631/Default.aspx. Accessed July 29, 2011.

- 2.The Joint Commission. Primary Care Medical Home. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/accreditation/pchi.aspx. Accessed July 29, 2011.

- 3.Medicare and Medicaid programs; electronic health record incentive program: final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75(144):44313–44588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare and Medicaid programs; opportunities for alignment under Medicaid and Medicare: proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76(94):28196–28207 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fielding JE, Teutsch SM. Integrating clinical care and community health: delivering health. JAMA. 2009;302(3):317–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hripcsak G, Soulakis ND, Li Let al. Syndromic surveillance using ambulatory electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(3):354–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle TJ, Glynn K, Groseclose SL. Completeness of notifiable infectious disease reporting in the United States: An analytical literature review. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:866–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konowitz PM, Petrossian GA, Rose DN. The underreporting of disease and physicians’ knowledge of reporting requirements. Public Health Rep. 1984;99:31–35 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lurio J, Morrison FP, Pichardo Met al. Using electronic health record alerts to provide public health situational awareness to clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(2):217–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrett NY, Mishra N, Nichols Bet al. Characterization of public health alerts and their suitability for alerting in electronic health record systems. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(1):77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokarz R, Kapoor V, Wu Wet al. Longitudinal molecular microbial analysis of influenza- like illness in New York City, may 2009 through may 2010. Virol J. 2011;8:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dexheimer J, Talbot T, Sanders Det al. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:311–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald Het al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293:1223–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farley TA, Dalal MA, Mostashari F, Frieden TR. Deaths preventable in the U.S. by improvements in the use of clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):600–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teutch SM, Fielding JE. Closing the gap in clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):684–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frieden TR. Take Care New York: a focused health policy. J Urban Health. 2004;81(3):314–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):138–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall T. Identification of patients for clinical risk assessment by prediction of cardiovascular risk using default risk factor values. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaul KD, Branstetter AD, Schrpeder DM, Glasgow RE. What is the relationship between breast cancer risk and mammography screening? A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology. 1996;15(6):423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewer NT, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Chapman GB, McCaul KD. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EEet al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lok ASF, McMahon BJ. AASLD Practice Guideline Update. Chronic Hepatitis B: Update. Alexandria, VA: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell L. Measuring the Gaps: Collecting Data to Drive Improvements in Health Care Disparities. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bierman AS, Nicole L, Collins KSet al. Addressing racial and ethnic barriers to effective health care: the need for better data. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wynia M, Hasnain-Wynia R, Hotze Tet al. Collecting and Using Race, Ethnicity and Language Data in Ambulatory Settings: A White Paper With Recommendations From the Commission to End Health Care Disparities. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 124 Stat. 119(2010). Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/content-detail.html. Accessed July 29, 2011.

- 28.Institute of Medicine Race, Ethnicity and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsiao C-J, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B. Electronic Medical Record/Electronic Health Record Systems of Office-based Physicians: United States, 2009 and Preliminary 2010 State Estimates. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Health E-stat. December 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/emr_ehr_09/emr_ehr_09.htm. Accessed January 2, 2012 [Google Scholar]