Abstract

Global health should encompass circumpolar health if it is to transcend the traditional approach of the “rich North” assisting the “poor South.” Although the eight Arctic states are among the world’s most highly developed countries, considerable health disparities exist among regions across the Arctic, as well as between northern and southern regions and between indigenous and nonindigenous populations within some of these states.

While sharing commonalities such as a sparse population, geographical remoteness, harsh physical environment, and underdeveloped human resources, circumpolar regions in the northern hemisphere have developed different health systems, strategies, and practices, some of which are relevant to middle and lower income countries.

As the Arctic gains prominence as a sentinel of global issues such as climate change, the health of circumpolar populations should be part of the global health discourse and policy development.

In recent years the term “global health” has largely replaced “international health” and attempts have been made to promote a standardized definition.1–3 Despite its intention to move beyond the mindset of international development assistance implicit in “international health,” global health is still very much preoccupied with how the “rich North” can contribute to improving the health of low- and middle-income countries in the “poor South.” Thus, most grants on global health offered by governmental and nongovernmental agencies are usually restricted to interventions in low- and middle-income countries.

In this Commentary we argue that an important perspective—the circumpolar one—has been missing in the global health discourse and that the circumpolar perspective has much to contribute and gain by being part of global health research, practice, and policy development. The usual “north–south” orientation in exchanges and dialogue is given a new twist in that the northern regions within the rich North can be considered part of the low-income “South” in some respects. Global health concerns do not stop at high latitudes.

DEFINING CIRCUMPOLAR

The lack of awareness of the circumpolar world is exemplified in a map accompanying an article on global trends in infant and child mortality published by a prestigious medical journal.4 The world’s largest island—Greenland—has completely disappeared, and is replaced by ocean! It is all the more ironic in that there is no lack of health indicator data from Greenland, where a high quality national statistical system exists and extensive health research has been undertaken for decades.5

The eight countries that are members of the Arctic Council (Canada, Denmark with its self-governing territories of Greenland and Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States) constitute some of the world’s most industrialized and developed nations. With the exception of Russia, these Arctic States occupy the highest ranks in most health indicators. For example, in 2010, Norway, the United States, Canada, and Sweden ranked within the top 10, and Finland, Iceland, and Denmark ranked within the top 20 on the Human Development Index, while Russia ranked sixty-fifth.6 Yet substantial health disparities exist across the northern regions in different countries, and between the northern and southern regions within countries. Global health maps often gloss over the large health gaps that exist in some northern regions such as Nunavut in Canada by assigning it the same color code as the rest of the country. Nation-based comparisons thus dilute and hide important regional challenges within countries.

What constitutes the circumpolar world? We have identified 27 regions (Figure 1) that constitute the northernmost administrative units of the Arctic states (Alaska; the three northern territories of Canada; the northern counties of Norway, Sweden, and Finland; and various northern republics, oblasts, and autonomous regions of the Russian Federation) and several island-states in the North Atlantic (Greenland, Iceland, and Faroe Islands). All these regions are either wholly or have part of their territories located above 60°N. Together they encompass 17 million square kilometers, slightly more than 10% of the planet’s total land area, with a total population of just under 10 million. Note that in this article we use the term “circumpolar” to refer to the northern hemisphere only, thus excluding from consideration the Antarctic with its small transient population.

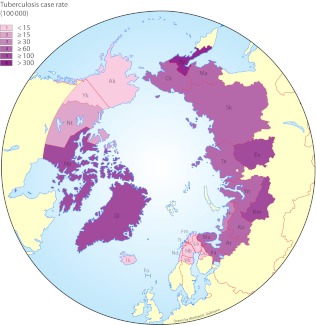

FIGURE 1—

Map of circumpolar regions showing mean annual incidence rate of new cases, 2000–2004 period.

Note. Ak = Alaska; Ar = Arkhangelsk; Ck = Chukotka; Ev = Evenkia; Fm = Finnmark; Fo = Faroe Islands; Gl = Greenland; Is = Iceland; Ka = Kareliya; Km = Khanty-Mansi; Ko = Komi; Ky = Koryak; La = Lappi; Ma = Magadan; Mu = Murmansk; Nb = Norbotten; Nd = Nordland; Ne = Nenets; Nt = Northwest Territories; Nu = Nunavut; Ou = Oulu; Sk = Sakha; Ta = Taymyr; Tr = Troms; Vb = Västerbotten; Yk = Yukon; Yn = Yamalo-Nenets

Source. Young.7

The population of the circumpolar regions is noted for its ethnic diversity, especially in the presence of many indigenous peoples, some of whom cross international boundaries (such as the Inuit, Athapaskans, and Sami). Indigenous people are the overwhelming majority in some regions such as Nunavut and Greenland, where they account for more than 85% of the total population.7 However, across the Arctic as a whole they are a small minority, yet they carry a disproportionate burden of disease as a result of rapid social and economic transitions.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

The health status of the 27 regions fall into four distinct patterns, which are remarkably consistent regardless of the health indicator used, whether the annual incidence rate of tuberculosis (Figure 1), life expectancy at birth, or infant mortality rate. The Nordic countries (including Iceland and Faroe Islands) tend to have the best health indicators, and there is little difference between northern and southern regions within these countries, or between the indigenous Sami and the majority population.8 Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories are similar in that their nonindigenous populations have a health status that is comparable (or even better) than the national population; however, their indigenous populations, accounting for 18%, 25%, and 50% of the total population of these three regions, respectively, tend to fare substantially worse. Greenland and Nunavut, inhabited predominantly by Inuit on opposite sides of Davis Strait, are remarkably similar in having health status that are substantially worse than that of Denmark and Canada—life expectancy about 10 years shorter, and infant mortality about three times higher.9 Russia as a whole is experiencing a health crisis and its northern regions have some of the worst health indicators among the 27 Arctic regions. As an example of interregional health disparities, the infant mortality rate during the period 2005 through 2009 in the worst region (Koryakia in Russia, 28/1000 live births) is 14 times that of the best region (Iceland, 2/1000 livebirths).7

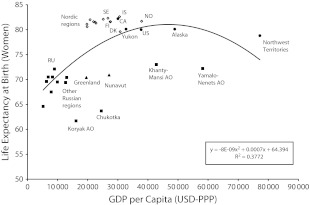

The social determinants of health are as important in circumpolar regions as elsewhere. The relationship between health status and measures of economic well-being such as per capita gross domestic product (GDP), however, is in the shape of an inverted U (Figure 2). In the Arctic, the observation that “more wealth = better health” is distorted by the fact that large scale natural resource development (oil, gas, diamond mining) in several regions has resulted in their very high GDP, while the overall health of the population lags behind that of other regions without such developments. Globally, parallel situations can be found in certain oil and mineral-rich countries in the Middle East and Africa compared with their less well-endowed neighbors. GDP also masks the fact that wealth generated within the Arctic tends to leave the regions, and that it is also not equitably distributed within the regions. Again, ample examples exist globally.

FIGURE 2—

Relationship between per capita gross domestic product and life expectancy at birth for females among circumpolar regions.

Note. AO = autonomous Okrug; CA = Canada; DK = Denmark; GDP = gross domestic product; FI = Finland; IS = Iceland; NO = Norway; PPP = purchasing power parity; RU = Russia; SE = Sweden; US = United States. Equation in figure refers to fitted quadratic regression equation.

Source. Life expectancy at birth and GDP per capita data from Young.7

Different health care systems have evolved in the 27 Arctic regions. While generally reflective of the larger national health systems (such as health care financing), these regional systems also attempt to adapt to the widely dispersed and sparse population, harsh physical environment, and underdeveloped human resources. These regional health care systems differ in their governance and organization, integration of primary care with public health, intersectoral coordination, reliance on nonphysician personnel in extended roles, special consideration for culturally appropriate care to indigenous people, human resources management and development, and the use of innovative information technologies. On a per capita basis and relative to national norms, health care is generally more expensive in Alaska, northern Canada, and northern Russia, whereas in the other regions, they are not significantly different from the rest of the country. Greenland is unique in having a per capita expenditure that is only 60% that of Denmark.10 Few internationally comparable health system indicators beyond per capita expenditures are consistently available across the circumpolar North.

LESSONS FOR OTHERS

Circumpolar countries and regions have much to learn from one another.11 Collectively they also have valuable lessons to offer other countries, especially low- and middle-income countries. Marginalized populations exist in many of these countries, with perhaps even wider health disparities. The geography of scattered, far-flung communities with health care challenges is certainly not unique to the Arctic. Temperate and tropical countries have islands, oases, outposts, etc., that can benefit from the solutions of circumpolar regions, especially in the use of telecommunication and transportation, and the training and deployment of locally recruited health workforce. Despite their being in some of world’s richest countries, circumpolar regions also lack capacity in advanced higher education and health research,12 and thus can benefit from innovations in these areas developed in resource-poor countries.

Circumpolar regions are overlooked by the World Health Organization, which has mostly been engaged in programs that are targeted at low- and middle-income countries. When it was announced that Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper would cochair the UN Commission on Women and Children’s Health, leaders of northern indigenous people such as the Inuit applauded its goals but stressed the equally pressing needs of northern indigenous women and children, who are excluded from this “global” initiative.13

GLOBAL LINKAGES

Circumpolar health practitioners, researchers, and policymakers have developed their own mechanisms for international collaboration such as the triennial congresses, national societies, and networks of researchers, with increased activities over the recent International Polar Year (2007–2008).14,15 The intergovernmental Arctic Council created in 1996, which also includes indigenous people’s organizations as “permanent participants,” has been primarily focused on political and environmental issues, and human health has been of peripheral interest and subsumed under sustainable development and environmental monitoring. The creation of the Arctic Human Health Expert Group in 2009 reflects the Council’s recognition of the need for health perspectives. In February 2011, the health ministers of Arctic States met in Greenland and jointly issued the Nuuk Declaration, outlining areas of common concerns and priorities for action.16 It remains to be seen how national and regional governments respond and translate this declaration into concrete health policies.

The Arctic has gained global prominence in recent years. It is now seen as a sentinel of the consequences of global climate change.17 It has also gained strategic importance because of its untapped natural resources and increased commercial and military potential. Inuit organizations have drawn international attention to the devastating impact of climate change on their way of life.18 Northern indigenous people have joined forces with “small island developing states” in programs such as Many Strong Voices to address adaptation to global climate change.19

In conclusion, we propose that for global health to be truly global, it needs to include the circumpolar perspective. Circumpolar health is global health.

Human Participant Protection

No human participants were used and institutional review board approval was not needed.

References

- 1.Banta JE. From international to global health. J Community Health. 2001;26:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TM, Cueto M, Fee E. The World Health Organization and the transition from “international” to “global” public health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:62–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MHet al. for the Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373:1993–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajaratnam JK, Marcus JR, Flaxman ADet al. Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970-2010: a systematic analysis of progress towards the Millennium Development Goal 4. Lancet. 2010;375:1988–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerregaard P, Stensgaard P. Greenland. : Young TK, Bjerregaard P, Health Transitions in Arctic Populations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2008:23–38 [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report 2010. New York: United Nations, 2010. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi. Accessed August 27, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young TK. Circumpolar health indicators: sources, data, and maps. Circumpolar Health Suppl. 2008; (3):10–128 Available at: http://circhob.circumpolarhealth.org. Accessed August 27, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassler S, Kvernmo S, Kozlov A. Sami. : Young TK, Bjerregaard P, Health Transitions in Arctic Populations, Chapter 9. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2008:148–170 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjerregaard P, Young TK, Dewailly E, Ebbesson SOE. Indigenous health in the Arctic: an overview of the circumpolar Inuit population. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young TK. Data brief from the Circumpolar Health Observatory: health expenditures. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2010;69:417–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young TK, Chatwood S. Health care in the North: what Canada can learn from its circumpolar neighbours. CMAJ. 2010;183:209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatwood S, Young TK. A new approach to health research in Canada’s North. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:25–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami President’s Statement, January 10, 2010. CMAJ studies on Inuit wellbeing underscore PM’s call for action on maternal and child health. Available at: http://www.itk.ca/media-centre/statements/cmaj-studies-inuit-wellbeing-underscore-pm’s-call-action-maternal-and-child-health. Accessed June 14, 2011

- 14.Chatwood S, Johnson R, Parkinson A. Circumpolar health collaborations: a description of players and call for further dialogue. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011; in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkinson A, Chatwood S. Human Health. : Krupnik I, Allison I, Bell Ret al. Understanding Earth’s Polar Challenges: International Polar Year 2007-2008. Summary by the IPY Joint Committee. Edmonton: ICSU-WMO, Canadian Circumpolar Institute; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arctic Council. Arctic health cooperation – a first step. 17 February 2011. Available at: http://arctic-council.org/article/2011/2/arctic_health_cooperation. Accessed June 14, 2011.

- 17.Arctic Climate Impact Assessment Impacts of a Warming Arctic. Overview Report. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petition to the Inter American Commission on Human Rights Seeking Relief from Violations Resulting from Global Warming Caused by Acts and Omissions of the United States Submitted by Sheila Watt-Cloutier, with the support of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, on behalf of all Inuit of the Arctic Regions of the United States and Canada. Available at: http://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/files/uploads/icc-files/FINALPetitionICC.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2011

- 19.Many Strong Voices Five-Year Action Plan. June 2008. Available at: http://www.manystrongvoices.org/files/2007%20Deliverables/Five-year%20Action%20Plan.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2011 [Google Scholar]