Abstract

Oxidative stress is caused predominantly by accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and distinguishes inflamed tissue from healthy tissue. Hydrogen peroxide could potentially be useful as a stimulus for targeted drug delivery to diseased tissue. However, current polymeric systems are not sensitive to biologically relevant concentrations of H2O2 (50-100 μM). Here we report a new biocompatible polymeric capsule capable of undergoing backbone degradation and thus release upon exposure to such concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. Two polymeric structures were developed differing with respect to the linkage between the boronic ester group and the polymeric backbone: either direct (1) or via an ether linkage (2). Both polymers are stable in aqueous solution at normal pH, and exposure to peroxide induces the removal of the boronic ester protecting groups at physiological pH and temperature, revealing phenols along the backbone, which undergo quinone methide rearrangement to lead to polymer degradation. Considerably faster backbone degradation was observed for polymer 2 over polymer 1 by NMR and GPC. Nanoparticles were formulated from these novel materials to analyze their oxidation triggered release properties. While nanoparticles formulated from polymer 1 only released 50% of the reporter dye after exposure to 1 mM H2O2 for 26 h, nanoparticles formulated from polymer 2 did so within 10 h and were able to release their cargo selectively in biologically relevant concentrations of H2O2. Nanoparticles formulated from polymer 2 showed a two fold enhancement of release upon incubation with activated neutrophils while controls showed non specific response to ROS producing cells. These polymers represent a novel, biologically relevant and biocompatible approach to biodegradable H2O2-triggered release systems that can degrade into small molecules, release their cargo, and should be easily cleared by the body.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, Reactive oxygen species, bioresponsive materials, polymer degradation, hydrogen peroxide, nanoparticles, biocompatible delivery

Introduction

The contribution of oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) to the development of numerous diseases has resulted in a research focus to create ROS-specific detection systems1-7 and ROS-responsive micro-7 or nanocarriers.8-13 Oxidative stress is a condition in which the balance of oxidative and reducing species within cellular environments has been disturbed. Once out of balance, ROS such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxide radicals can damage cellular components.14 Although some ROS are key to cell signaling15 and defense mechanisms, these chemicals also contribute to various diseases.16-18

Methods of selective delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic reagents to sites undergoing oxidative stress would prove useful for the numerous diseases characterized by high concentrations of ROS. Polymer-based nano- and microparticles are especially useful because they can be tailored to degrade upon encountering certain stimuli,19 such as enzymatic removal of a protecting group,20-21 pH,22-24 light,25-26 and H2O2.3,5,10,27-28 Upon encapsulation, nanoparticles can provide improved pharmacokinetics, as the therapeutic drug is protected from the physiological environment and selected release allows for lower drug loading through effective site delivery.29 To our knowledge, there are few if any polymeric systems able to undergo degradation and cargo release on encountering biologically relevant (50-100 μM) H2O2 concentrations. One important study showed a polymeric carrier responsive to 1 mM H2O2 in a useful time frame using dextran reversibly modified with aryl boronic esters, this system utilized a carbonate ester linkage, and took advantage of a solubility switching mechanism to release its payload.8 Notably, this study also demonstrated the advantage of such boronic ester stabilized nanomaterials for promoting immune activation by antigen-presenting cells.

In this paper, we report a complementary polymeric system specifically sensitive to biologically relevant concentrations of H2O2, where aryl boronic ester protecting groups are introduced into each motif of our polymeric nanoparticle design.26 This results in an amplification of the H2O2 sensitivity, because each cleavage of the boronic ester leads to polymer backbone degradation. High molecular weight polymers can be formulated into particles and such degradation of the polymer backbone is likely responsible for this systems high sensitivity to H2O2. Furthermore, the degradation products are smaller molecular weight species that are predicted to be more easily cleared by the body than larger polymer molecules. Moreover, we can modulate the kinetics of degradation using two linkage strategies between the peroxide activated triggering group and the backbone. A recent study has shown that an ether linkage strategy provides both high hydrolytic stability and cleavage kinetics, though it has been only sparsely utilized.30 This chemistry has been used most notably for the synthesis of ROS sensitive prodrugs to inhibit matrix metalloproteinase, an enzyme which is secreted as a ROS sensitive zymogen, and implicated in the reperfusion injury associated with stroke.31

Here, we use these polymers to encapsulate small hydrophobic molecules and measure their release upon exposure to biologically relevant oxidative conditions. This new material represents an addition to the very small toolbox of systems with the potential to target drug delivery to oxidative conditions.

Result and Discussion

Design of H2O2-sensitive polymers

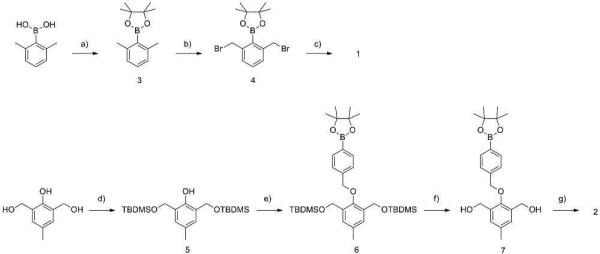

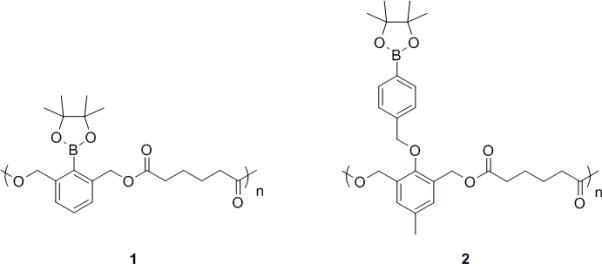

Polymer 1 and polymer 2 (shown in Figure 1) differ in the linkage type between the pendant boronic ester protecting groups and the polymer backbone. Polymer 1 has a direct linkage between the polymer backbone and the protecting group, while polymer 2 has a benzylic ether boronic ester pendant to the backbone.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of Polymer 1 and 2

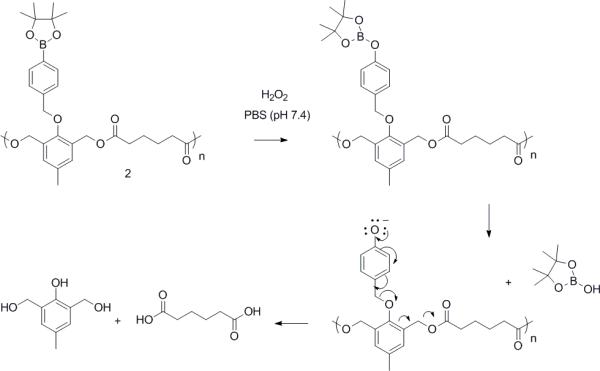

Mechanism of H2O2-induced polymer degradation

Upon exposure to H2O232-34 the aryl boronic ester group is oxidized, and subsequently hydrolyzed to unmask a phenol. This initiates a quinone methide rearrangement3,31,35-37 to degrade the polymer (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of polymeric particle 2 degradation upon exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

Monomer and Polymer synthesis

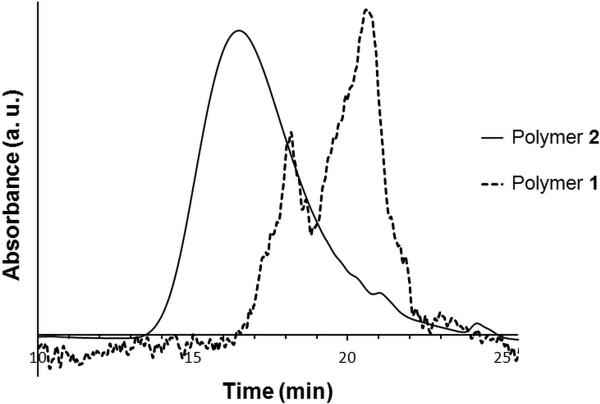

H2O2 sensitive nanoparticles were formulated from polymer 1 and 2. The synthesis of 1 (Scheme 2) began with the protection of 2,6-dimethylphenylboronic acid with pinacol which afforded good yields (84%) of boronic ester 3. Subsequent benzylic bromination with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and 2,2’-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile (AIBN) gave the desired monomer (55% yield). The monomer was then combined with adipic acid in the presence of a phase transfer catalyst,38 Bu4NOH, to give the H2O2 reactive polymer (PS standard: Mw=10623, PDI=1.9). The GPC (Figure 2, dashed line) for this polymer is not smooth and has a high PDI, consistent with a step growth polymerization. As this direct linkage polymer is synthetically challenging,30 we were only able to isolate short polymeric strands. However, we were able to successfully formulate particles and encapsulate Nile red within, thus the molecular weight was sufficient for controlled release. Other methods of polymerization were extensively investigated. Pyridine in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and dimethylformamide (DMF) failed to give high conversion to polymer. 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) in DMSO also successfully provided polymer 1 with a similar degree of polymerization. Alternative routes of polymerization were also explored, such as hydrolysis of benzyl bromide 4 followed by a subsequent reaction with adipoyl chloride. Unfortunately, the desired hydrolysis product of 4 could not be isolated.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of H2O2 degradable polymer 1 and 2. a) pinacol, C6H6 (84%), b) AIBN, NBS, CCl4 (55%), c) adipic acid, Bu4NOH, CHCl3 (96%), d) TBDMSCl, imidazole, DMF (95%), e) 4-Bromomethylphenyl boronic acid pinacol ester, K2CO3, DMF (79%), f) p-TsOH, MeOH (90%), g) adipoyl chloride, pyridine, DCM (82%).

Figure 2.

GPC traces of polymer 1 (Mw = 10.6 kDa, PDI = 1.9) and 2 ( Mw = 51.3 kDa, PDI = 1.4)

Much better synthetic accessibility was observed for polymer 2 (Scheme 2). Polymer 2 was synthesized with slight modifications according to a previously published procedure.26,37 First, selective protection of 2,6-bis(hydroxymethyll)-p-cresol with tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (TBDMSCl) afforded 5 in good yield (95%). The phenol of 5 was then combined with 4-(hydroxymethyl)phenylboronic acid pinacol ester to provide the protected boronic ester 6. Removal of the TBS protecting groups provided monomer 7, which is capable of copolymerization with adipoyl chloride. GPC data showed a higher degree of polymerization for 2 compared to 1 (Figure 2, solid line), which is not unexpected as the polymerization methods are different.

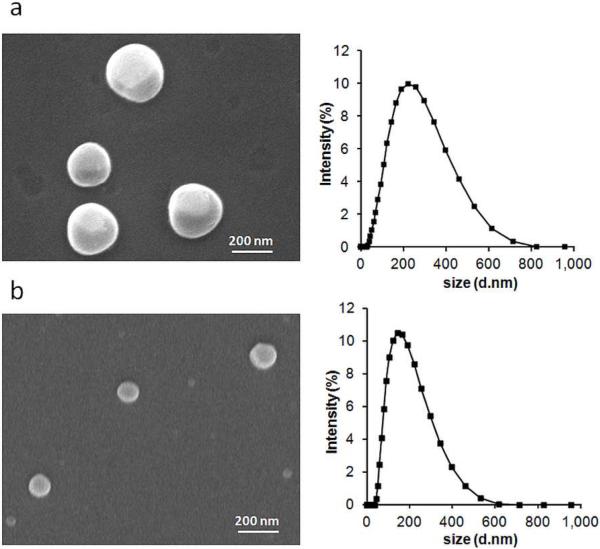

Nanoparticle Characterization

We formulated polymers 1 and 2 into nanoparticles via an oil/water emulsion technique. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis indicated the formation of nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 150 nm (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Characterization of polymeric particles by SEM and DLS a) 1 (d = 166 nm (std dev 5.7), PDI = 0.38 (std dev 0.07)) and b) 2 (d = 136 nm (std dev 5.4), PDI = 0.30 (std dev 0.01)).

Evaluation of controlled release

We also formulated polymers 1 and 2 into nanoparticles encapsulating a solvatochromic dye, Nile red, to monitor hydrogen peroxide-triggered release from these polymeric nanoparticles. The encapsulation efficiency was determined by fluorescence and HPLC (50 % and 44 %, respectively). The fluorescence of the dye is quenched in aqueous environments, enabling use as a model compound to indicate small molecule release from the hydrophobic nanoparticle interior. Prior to the evaluation of controlled release from our materials, the stability of Nile Red fluorescence in hydrogen peroxide was tested to ensure that the fluorescence quenching observed is not a result of Nile Red exposure to hydrogen peroxide. Nile Red fluorescence does not change significantly over the course of 72 h of incubation with the highest hydrogen peroxide concentration used in our study (1mM, Figure S1†).

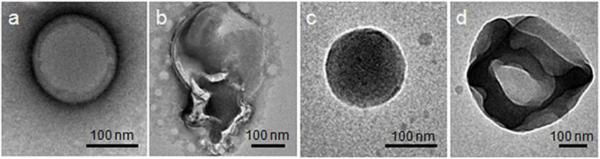

Exposure to 1 mM H2O2 (in PBS, pH = 7.4) decreased the fluorescence intensity of Nile red in both nanoparticle formulations (Figure 4). A red shift from around 625 to 640 nm, indicating that the environment of the dye had been altered, was also observed. For nanoparticles prepared using polymer 1, a 50% decrease in fluorescence is observed at 26 h. This result agrees with our TEM images (Figure 4b) of the degraded empty particles upon exposure to the same H2O2 concentration (1 mM), which indicate release of the dye. Because the nanoparticles fall apart (Figure 4), Nile Red is now exposed to a more polar medium, resulting in fluorescence quenching. In the absence of H2O2, Nile red maintains 80% of its fluorescence at 622 nm over 6 days. This slight decrease may result from quenching of Nile red adsorbed onto the surface of the particles.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence of Nile red upon release from nanoparticles in PBS (pH 7.4) of 1 and 2 in the absence or presence of various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, as a function of incubation time at 37° C.

Nanoparticles made from polymer 2, containing an ether linkage, degraded about an order of magnitude more rapidly in response to peroxide and were similarly stable in the absence of peroxide (Figure 4a). Exposure to 100 μM H2O2 induced a 50% decrease in Nile red fluorescence for these nanoparticles, while those from polymer 1 required 1 mM H2O2 to release to the same degree. Thus, polymer 2 is sensitive to biologically relevant concentration of H2O2 (50-100 μM)39 (Figure 4b). Exposure to 1mM H2O2 resulted in complete quench of the dye within a day. These release kinetics agree with the recent finding (in the context of H2O2 activated metalloprotein inhibitors) of faster conversion of the boronic ester to the phenol by prodrugs employing an ether linkage than those with a direct linkage.30

H2O2–induced nanoparticle degradation

After formation and purification, nanoparticle degradation was investigated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Direct visualization by TEM reveals how polymer degradation affects nanoparticle structure. Contrary to indirect methods using light scattering or transmission, direct visualization of the particles morphology by TEM can detail any significant changes in the morphology of the nanoparticles after treatment with H2O2. Representative particles are presented; additional TEM images of particles in the absence and presence of varied concentrations of H2O2 (250 mM, 100 mM, 100 μM, and 50 μM) are presented in Figures S2-S6. Almost all nanoparticles are spherical and intact in the absence of H2O2 (Figure 5a (1) and 5c (2)). Exposure to 1 mM hydrogen peroxide induces significant ripping or crumpling of the structures, as well as particle expansion, in most particles (Figure 5b (1) and 5d (2).

Figure 5.

TEM images of nanoparticles 1 (a-b) and 2 (c-d). a, c) after 72 h of incubation in PBS; b, d) after 72 h in PBS containing 1 mM H2O2.

Similar morphological changes were observed for nanoparticles 1 and 2 in the presence of 100 mM (3 min) or 250 mM (10 min) but the ratio between intact and degraded was much more balanced. Interestingly, for nanoparticles 2, this combination of intact and degraded particles was also observed at low concentrations of H2O2 (100 μM and 50 μM). This supports our conclusion that physiological concentration of peroxide induces polymer 2 degradation.

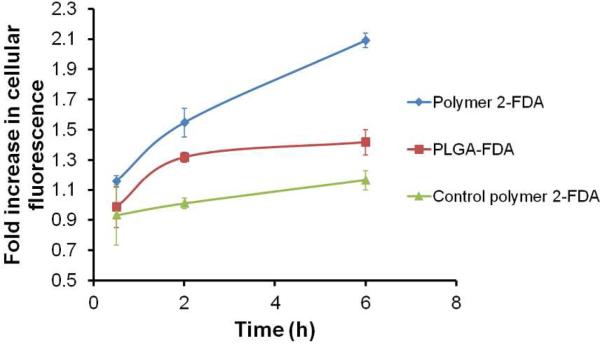

Particle payload release with and without activating ROS production in neutrophils

Activated neutrophils generate high ROS. We measured extracellular hydrogen peroxide produced by neutrophils (differentiated mouse promyelocytes or dMPRO cells) with and without PMA (phorbol 12 myristate 13 acetate) stimulation. After 6h of PMA treatment, 1.6 × 106 dMPRO cells produced 6.5 μM H2O2, while untreated cells produced 4.5 μM H2O2. These extracellular levels of H2O2 were much lower than the levels we previously looked at for polymer 2, however the concentration of H2O2 inside neutrophil granules maybe much higher 40. For the release assay we chose fluorescein diacetate (FDA), a non-fluorescent molecule which is cleaved to fluorescein (Ex490/Em520) by cellular esterases. FDA encapsulated in nanoparticles fabricated from polymer 2, from PLGA and from a control polymer similar in structure to polymer 2 (with a protecting group that does not cleave in the presence of ROS26) were added to PMA treated and untreated dMPRO cells and fluorescence was measured at different time points (0.5, 2 and 6 h). Release of FDA was calculated as the ratio of fluorescence from PMA treated to untreated cells (Figure 6). Overall a two fold increase in release of FDA from nanoparticles of polymer 2 was observed in stimulated dMPRO cells while PLGA showed no further release after the initial burst release observed in the first 2h period. Nanoparticles from control polymer 2 showed a non-specific response.

Figure 6.

Fold increase in cellular fluorescence after PMA stimulation after 0.5, 2 and 6h.

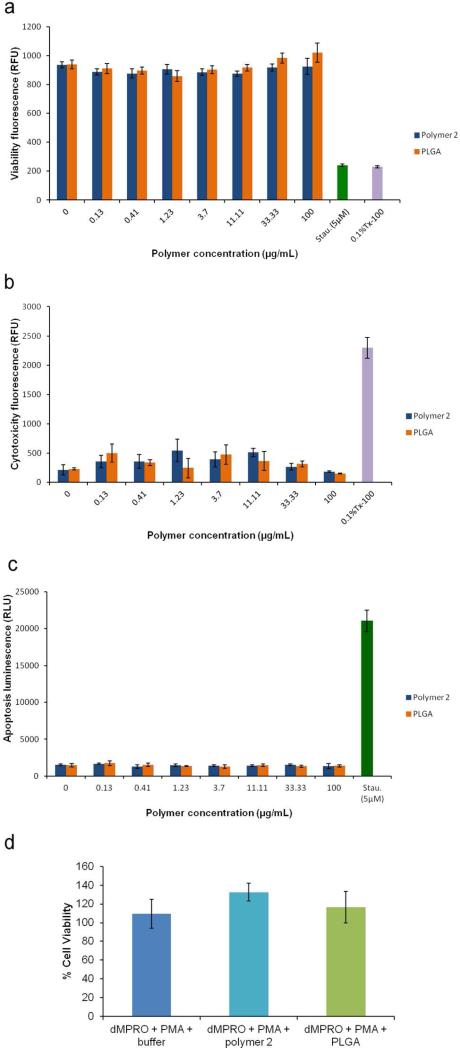

Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles from polymer 2

As nanoparticles from polymer 2 could provide ROS controlled cargo release upon exposure to biologically relevant oxidative conditions, we tested their cytotoxicity by Apotoxglo assay, which measures live and dead cell protease activity to assess viability and cytotoxicity, respectively. In addition, this assay also measures caspase 3/7 activity as a readout for apoptosis (Figure 7). We compared the effect of these nanoparticles on Raw264.7 macrophages with that of the nontoxic FDA-approved polymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles. Staurosporine and 0.1% Triton-X 100 were used as positive controls for induction of apoptosis and cell death, respectively. No significant differences were observed between PLGA and polymer 2 nanoparticles up to a concentration of 100 μg/mL (p > 0.05). Upon incubation for three different time intervals (5h, 24h and 48h), neither polymer 2 nor PLGA induced any significant toxicity (cell death or apoptosis) compared to untreated cells (Figure 7 a-c and Figure S7). On the other hand, apoptosis and loss of cell viability was observed in cells treated with staurospoine and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Figure 7 a-c). To test if polymer 2 nanoparticles affect viability of activated neutrophils (which would mimic pathological conditions in vivo), we incubated polymer 2 and PLGA nanoparticles for 4h with activated neutrophils (phorbol 12 myristate 13 acetate-stimulated dMPRO cells). Cell viability post-incubation was measured by trypan blue staining; no loss in cell viability was seen in either case (Figure 7 d).

Figure 7.

a-c. Cytotoxicity analysis (a: viability, b: cytotoxicity, c: apoptosis), of the H2O2 degradable nanoparticles from polymer 2 and PLGA nanoparticles incubated for 5hrs at different concentrations with Raw264.7 cells using Apotoxglo assay. d. Percent cell viability of phorbol 12 myristate 13 acetate (PMA)-stimulated differentiated promyelocytes (dMPRO) after incubation in buffer, polymer 2 nanoparticles and PLGA for 4h.

Polymer degradation

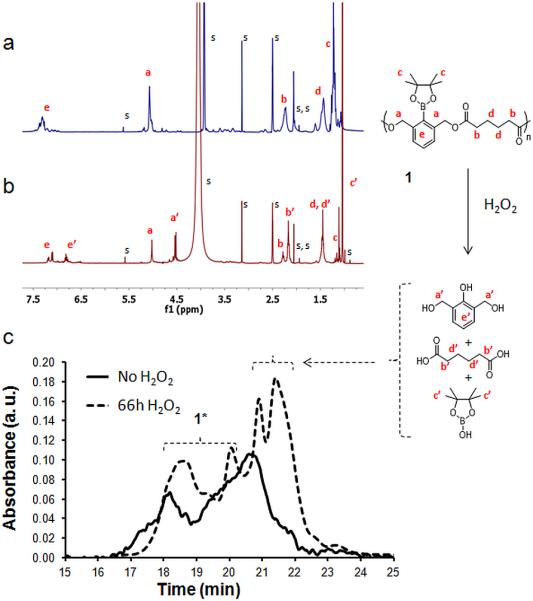

After validating that degradation of polymer 2 at biologically relevant oxidative levels initiates payload release, we characterized degradation by GPC and NMR. High concentrations of H2O2 were used to fully degrade the polymers and confirm that the polymers degrade into predicted products (Scheme 1).

The degradation of polymer 1 was examined in 250 mM H2O2 in a 20% PBS/DMF (v/v) solution by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and NMR (Figure 8). GPC following 66 h exposure to peroxide revealed small molecule peaks corresponding to products of degradation of polyester 1, adipic acid and 2,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)phenol (cresol) (Scheme 1) that constitute 35% of the peak area (Figure 8c). The chemical composition of the small molecule products was confirmed by NMR (Figure 8b). As the rate of polymer degradation depends on H2O2 concentration, high concentrations of H2O2 (500 mM) were used. NMR peak shifts corresponding to the formation of cresol and the liberation of adipic acid were observed; the ester bonds of the polymer degrade to carboxylic acids and alcohols. The benzyl proton peaks shift from 5.03 to 4.54 ppm, indicating a change from the ester to the benzyl alcohol. Furthermore, protons alpha to the ester carbonyl shifted from 2.28 to 2.16 ppm, corresponding to protons of adipic acid.

Figure 8.

a, b) 1H NMR spectra of polymer 1 in DMSO-d6, deuterium PBS a) without H2O2 b) incubated with 500 mM H2O2 after 46 h at 37° C. Solvent peaks (s) include DMSO-d6, D2O and traces of water, ethyl acetate, methanol and dichloromethane. c) GPC chromatograms of the polymer prior to the addition of H2O2 (solid line) and after degradation in 20% PBS/DMF solutions containing 250 mM H2O2 incubated at 37° C (dotted line). 1* protected and deprotected polymer.

NMR shows clear evidence that the target degradation products are formed. However, chemical shifts from the remaining polymer, both protected and deprotected, are still observed by NMR (at 46 h) and by GPC (at 66 h), indicating that degradation into small molecules or oligomers is not complete in the time frame investigated. Polymer 1 thus has slow and incomplete degradation. However, this result is not unexpected, as conversion of the boronic ester to the phenol using a direct linkage strategy is slow. However, when formulated into nanoparticles, TEM and Nile Red release experiments showed that the observed polymer degradation could translate into sufficient particle degradation to result in release of an encapsulated payload.

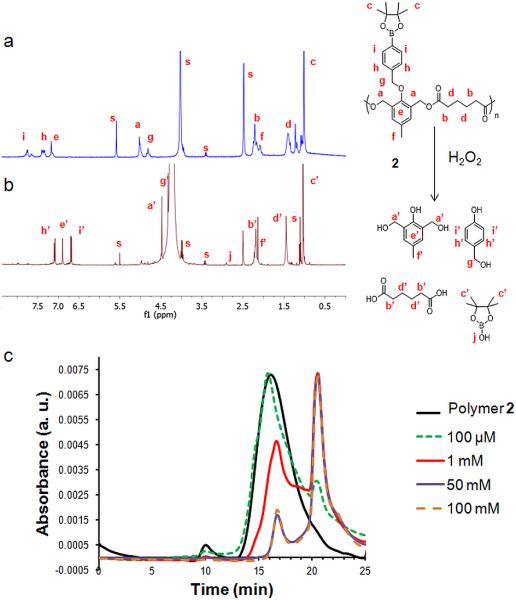

Degradation of polymer 2 was quantified as for 1, first by 1H NMR , in the absence of H2O2 or with 50 mM H2O2. As shown in Figure 9a-b, complete degradation occurred within 3 days, as broad peaks corresponding to the polymer have been replaced by the sharp peaks of the degradation products. Contrary to what it has been found for 1, H2O2 driven, almost complete and fast degradation was found for 2, and this with at least one order of magnitude less H2O2 concentration.

Figure 9.

a, b) 1H NMR spectra of polymer 2 in DMSO-d6, deuterium PBS a) without H2O2 b) incubated with 50 mM H2O2 after 3 days at 37° C. s refers to solvent peaks (DMSO-d6, D2O and traces of water, ethanol and dichloromethane). c) GPC chromatograms of polymer 2 prior to the addition of H2O2 (black line) and after degradation in 20% PBS/DMF solutions containing 100 μM, 1 mM, 50 mM and 100 mM H2O2 incubated at 37 °C for one day

GPC analysis (Figure 9c) showed that polymer 2 depolymerized upon only 24 h of H2O2 at 50 mM exposure. In agreement with the previous NMR result, the polymer degraded completely after 3 days at this concentration. Interestingly, GPC reveals degradation started even with a biologically relevant H2O2 concentration (100 μM, green line). Importantly, neither 1 nor 2 are hydrolyzed in the absence of H2O2 (tested over 6 days).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have synthesized a bioresponsive polyester bearing boronic ester triggering groups that degrades upon exposure to low concentrations of H2O2. The degradation is induced by transformation of a boronic ester to a phenol, which undergoes a quinione methide rearrangement to break down the polyester backbone. Nanoparticles formulated from the polymer degrade and release contents upon exposure to 50 μM H2O2. Advantages of our system are good synthetic accessibility and hydrolytic stability, fast H2O2 triggered cleavage kinetics, good biocompatibility, and the formation of only small degradation molecules that should be easily cleared by the body.41

Polymer 2 nanoparticles could be used to deliver small molecules or ROS-quenching enzymes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase to treat chronic inflammatory diseases. These diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and rheumatoid arthritis, are associated with increased neutrophil recruitment 42-45. Degranulation of neutrophils and macrophages produces ROS, which contributes to tissue damage. Thus, using these nanoparticles to deliver drugs that inhibit neutrophil recruitment to sites of chronic inflammation could limit such damage46. Anti-neutrophil recruitment drugs include reparixin and SB 225002 (N-(2-hydroxy-4-nitrophenyl)-N’-(2-bromophenyl)urea), which act on the neutrophil chemokine receptor (CXCR2) and inhibit neutrophil migration47-48. Cytotoxicity analysis of polymer 2 nanoparticles indicates that these are well-tolerated by both macrophages and stimulated neutrophils. In rheumatoid arthritis, polymer 2 nanoparticles could be injected directly into the joint cavity, while for COPD, nanoparticle administration would likely involve a nebulizer. Ongoing investigations are dedicated to investigating the potential of these polymeric systems to deliver therapeutic and diagnostic agents specifically to tissues undergoing oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH New Innovator Award (DP 2OD006499) and KACST for funding. We also thank Viet Anh Nguyen Huu for his help with experiments using nanoparticles encapsulating FDA.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by the NIH Director's New Innovator Award 1DP2OD006499-01 and a King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology center grant to the Center of Excellence in Nanomedicine at UC San Diego.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental procedures for the synthesis of the polymer, characterization data (1H NMR, 13C NMR, ESI-MS), procedures for nanoparticles formulations, Nile Red and Paclitaxel release studies, effect of H2O2 on the fluorescence of Nile Red, additional SEM and TEM images, polymer degradation (GPC, 1H NMR), Cytotoxicity analysis of polymer 2 nanoparticles, calibration curves used for the Nile red encapsulation efficiency determination. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li CH, Hu JM, Liu T, Liu SY. Macromolecules. 2011;44:429. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van de Bittner GC, Dubikovskaya EA, Bertozzi CR, Chang CJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:21316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012864107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sella E, Lubelski A, Klafter J, Shabat D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3945. doi: 10.1021/ja910839n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srikun D, Miller EW, Dornaille DW, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4596. doi: 10.1021/ja711480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee D, Khaja S, Velasquez Castano JC, Dasari M, Sun C, Petros J, Taylor WR, Murthy N. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:765. doi: 10.1038/nmat1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang MCY, Pralle A, Isacoff EY, Chang CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15392. doi: 10.1021/ja0441716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu SS, Koblin RL, Zachman AL, Perrien DS, Hofmeister LH, Giorgio TD, Sung HJ. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:4357. doi: 10.1021/bm201328k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broaders KE, Grandhe S, Frechet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:756. doi: 10.1021/ja110468v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson DS, Dalmasso G, Wang LX, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, Murthy N. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:923. doi: 10.1038/nmat2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehor A, Hubbell JA, Tirelli N. Langmuir. 2005;21:411. doi: 10.1021/la0478043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napoli A, Valentini M, Tirelli N, Muller M, Hubbell JA. Nat. Mater. 2004;3:183. doi: 10.1038/nmat1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khutoryanskiy VV, Tirelli N. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;80:1703. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen BL, Johnson JD, Walker JP. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5263. doi: 10.1021/nn201477y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geronikaki AA, Gavalas AM. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening. 2006;9:425. doi: 10.2174/138620706777698481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkel T. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:247. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cachofeiro V, Goicochea M, de Vinuesa SG, Oubina P, Lahera V, Luno J. Kidney Int. 2008:S4. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drechsel DA, Patel M. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;44:1873. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liou GY, Storz P. Free Radical Res. 2010;44:479. doi: 10.3109/10715761003667554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esser Kahn AP, Odom SA, Sottos NR, White SR, Moore JS. Macromolecules. 2011;44:5539. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo W, Phillips ST. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9234. doi: 10.1021/ja104420k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewit MA, Gillies ER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18327. doi: 10.1021/ja905343x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murthy N, Xu MC, Schuck S, Kunisawa J, Shastri N, Frechet JMJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930644100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murthy N, Thng YX, Schuck S, Xu MC, Frechet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12398. doi: 10.1021/ja026925r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sankaranarayanan J, Mahmoud EA, Kim G, Morachis JM, Almutairi A. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5930. doi: 10.1021/nn100968e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin AP, Mynar JL, Ma YZ, Fleming GR, Frechet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9952. doi: 10.1021/ja0523035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fomina N, McFearin C, Sermsakdi M, Edigin O, Almutairi A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9540. doi: 10.1021/ja102595j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avital Shmilovici M, Shabat D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:3643. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heffernan MJ, Murthy N. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1340. doi: 10.1021/bc050176w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:615. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jourden JLM, Daniel KB, Cohen SM. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2011;47:7968. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12526e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jourden JLM, Cohen SM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:6795. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuivila HG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954;76:870. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuivila HG, Armour AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:5659. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown HC. Tetrahedron. 1961;12:117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haba K, Popkov M, Shamis M, Lerner RA, Barbas CF, Shabat D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:716. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HY, Jiang X, Lee DW. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2065. doi: 10.1021/ol900433g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sella E, Shabat D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9934. doi: 10.1021/ja903032t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodge P, ODell R, Lee MS, Ebdon JR. Polymer. 1996;37:1267. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halliwell B, Clement MV, Long LH. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winterbourn CC, Garcia RC, Segal AW. Biochem. J. 1985;228:583. doi: 10.1042/bj2280583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norman J. Anaesthesist. 1985;34:311. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noguera A, Batle S, Miralles C, Iglesias J, Busquets X, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Thorax. 2001;56:432. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quint JK, Wedzicha JA. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;119:1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wright HL, Moots RJ, Bucknall RC, Edwards SW. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1618. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou RC, Kim ND, Sadik CD, Seung E, Lan Y, Byrne MH, Haribabu B, Iwakura Y, Luster AD. Immunity. 2010;33:266. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gernez Y, Tirouvanziam R, Chanez P. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;35:467. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00186109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White JR, Lee JM, Young PR, Hertzberg RP, Jurewicz AJ, Chaikin MA, Widdowson K, Foley JJ, Martin LD, Griswold DE, Sarau HM. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarbock A, Allegretti M, Ley K. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;155:357. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.