Abstract

(E)-3-(Pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone O-(2-(3-18F-fluoropropoxy)ethyl) oxime ([18F]-PSS223) was evaluated in vitro and in vivo to establish its potential as a PET tracer for imaging metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5). [18F]-PSS223 was obtained in 20% decay corrected radiochemical yield whereas the non-radioactive PSS223 was accomplished in 70% chemical yield in a SN2 reaction of common intermediate mesylate 8 with potassium fluoride. The in vitro binding affinity of [18F]-PSS223 was measured directly in a Scatchard assay to give Kd = 3.34 ± 2.05 nM. [18F]-PSS223 was stable in PBS and rat plasma but was significantly metabolized by rat liver microsomal enzymes, but to a lesser extent by human liver microsomes. Within 60 min, 90% and 20% of [18F]-PSS223 was metabolized by rat and human microsome enzymes, respectively. In vitro autoradiography on horizontal rat brain slices showed heterogeneous distribution of [18F]-PSS223 with the highest accumulation in brain regions where mGluR5 is highly expressed (hippocampus, striatum and cortex). Autoradiography in vitro under blockade conditions with ABP688 confirmed the high specificity of [18F]-PSS223 for mGluR5. Under the same blocking conditions but using the mGluR1 antagonist, JNJ16259685, no blockade was observed demonstrating the selectivity of [18F]-PSS223 for mGluR5 over mGluR1. Despite favourable in vitro properties of [18F]-PSS223, a clear-cut visualization of mGluR5-rich brain regions in vivo in rats was not possible mainly due to a fast clearance from the brain and low metabolic stability of [18F]-PSS223.

Keywords: mGluR5, PET imaging, [18F]-PSS223, [11C]-ABP688, [18F]-FDEGPECO, autoradiography, microsome enzymes

Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a powerful non-invasive imaging technique which allows quantification of biochemical and pharmacodynamic processes in healthy and diseased states. In drug discovery and development, PET offers opportunities to investigate drug-target interactions in vivo and to monitor the effects of a drug candidate on the progression of a disease [1,2]. The design of PET probes which selectively target a particular receptor, enzyme or transporter is a major challenge in further advancement of PET technique. Besides analogues of endogenous substrates such as [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]-FDG) or [11C]- or [18F]-labelled amino acids [3,4], small synthetic organic molecules are emerging as promising scaffolds for the development of highly selective PET probes.

Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) is a seven transmembrane domain, G-protein coupled receptor, belonging to group I of the metabotropic glutamate receptors and it is mainly located postsynaptically [5-7]. mGluR5 is involved in long-term potentiation processes [8] and plays a role in several disorders of central nervous system (CNS) such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, Alzheimer and Parkinson’s disease [9-14]. It is considered an important future drug target and much attention has been given to the development of an optimal PET tracer for imaging of mGluR5 [15].

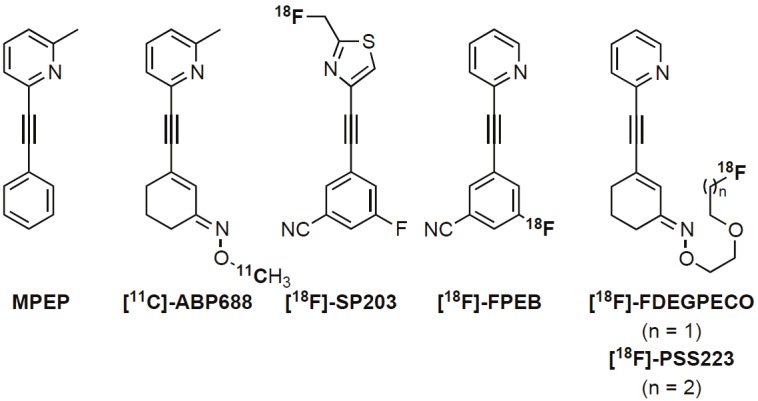

It was not until the development of synthetic mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-( phenylethynyl) pyridine (MPEP) [16,17], which unlike amino acid derived ligands acts via the non-competitive mechanism and not at the conserved glutamate binding site, that significant research efforts were made. This led to the development of (E)-3-((6-methylpyridin-2-yl)ethynyl) cyclohex-2-enone-O-11C-methyl oxime ([11C]-ABP688, Figure 1) by the Ametamey group [18,19] which is to date the most successful clinically applied mGluR5 PET tracer. Despite its excellent properties as a PET imaging agent in human subjects [19], [11C]-ABP688 does have one limitation and this is due to the short physical half-life (20 min) of carbon-11 which limits its application to facilities with an on-site cyclotron. This has provoked further research efforts towards the development of 18F-labelled PET tracers, which have a longer physical half-life (109.8 min). To date, the two most successful mGluR5 18F-labelled PET tracers are 3-fluoro-5-(2-(2-[18F](fluoromethyl)-thiazol-4-yl)-ethynyl) benzonitrile ([18F]-SP203) developed by the Pike group [20-22] and 3-[18F]fluoro-5-(2-pyridinylethynyl)benzonitrile ([18F]-FPEB) from the Hamill group [23-25] (Figure 1). However, the first undergoes significant defluorination in rodents and monkeys and to a lesser extent in humans and the latter is typically obtained in low radiochemical yields.

Figure 1.

Structures of MPEP and selected PET tracers for imaging of mGluR5

Our group aimed to develop a fluorine-18 analogue of [11C]-ABP688 with the same excellent imaging properties as [11C]-ABP688, but with added advantage of a longer physical half-life. Several derivatives were prepared [26,27] and evaluated which finally led to the development of (E)-3-(pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone O-(2-(2-18F-fluoroethoxy)ethyl) oxime ([18F]-FDEGPECO) [28,29], which maintained the same [11C]-ABP688 scaffold, but the oxime functionality was additionally adorned with a six-atom long lipophilic chain (as oppose to a methyl in [11C]-ABP688) [1,2,30,31]. The in vivo evaluation of [18F]-FDEGPECO allowed visualization of mGluR5 in the rat brain, albeit with a lower relative accumulation and shorter residence time in mGluR5-rich brain regions than observed for [11C]-ABP688, which prompted us to re-evaluate the structure of [18F]-FDEGPECO. The lipophilicity of [18F]-FDEGPECO is significantly lower than that of [11C]-ABP688 [18], and we chose to pursue an [18F]-FDEGPECO analogue (E)-3-(Pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone O-(2-(3-18F-fluoropropoxy)ethyl) oxime ([18F]-PSS223, Figure 1) in which the side chain functionality is extended by one methylene group with the aim to increase the lipophilicity towards that of [11C]-ABP688 [28,32].

In this manuscript we report on the synthesis, radiolabelling, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of this novel compound ([18F]-PSS223). The PET images of ([18F]-PSS223 are also compared with those obtained with [11C]-ABP688 and [18F]-FDEGPECO.

Materials and methods

General

All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were conducted in flame-dried glass apparatus under an atmosphere of inert gas. All chemicals and anhydrous solvents were purchased from Aldrich or ABCR and used as received unless otherwise noted. [3H]-ABP688 (2.405 GBq/mmol, 37 MBq/mL solution in EtOH) was obtained from AstraZeneca. 3-Ethynylcyclohex-2-enone, (E)-3-ethynylcyclohex-2-enone oxime and (E)-3-(pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone oxime (5) were prepared as previously reported and the characterization data is in complete agreement with those previously reported [28,33]. To obtain (E)-3-((6-Methylpyridin-2-yl)ethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone O-[11C]-methyl oxime ([11C]-ABP688) radiolabelling was performed using module system as previously described [18,34].

Preparative chromatographic separations were performed on Aldrich Science silica gel 60 (35-75 μm) and reactions followed by TLC analysis using Sigma-Aldrich silica gel 60 plates (2-25 μm) with fluorescent indicator (254 nm) and visualized with UV or potassium permanganate.

Infrared spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT/IR 6200 (OmniLab) spectrometer using a chloroform solution of compound. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in Fourier transform mode at the field strength specified on Bruker Avance FT-NMR spectrometers. Spectra were obtained from the specified deuterated solvents in 5 mm diameter tubes. Chemical shift in ppm is quoted relative to residual solvent signals calibrated as follows: CDCl3 δH (CHCl3) = 7.26 ppm, δC = 77.2 ppm; (CD3)2SO δH (CD3SOCHD2) = 2.50 ppm, δC = 39.5 ppm. Multiplicities in the 1H NMR spectra are described as: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, quint. = quintet, m = multiplet, b = broad; coupling constants are reported in Hz. Numbers in parentheses following carbon atom chemical shifts refer to the number of attached hydrogen atoms as revealed by the DEPT spectral editing technique. Electrospray (ES) mass spectra (LRMS) were obtained with a Micromass Quattro micro API LC electrospray ionization and electrospray (ES) mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained with a Bruker FTMS 4.7 T BioAPEXII spectrometer. Electron-impact (EI) and chemical ionisation (CI) mass spectra (LRMS and HRMS) were obtained with a Waters Micromass AutoSpec Ultima MassLynx 4.0 spectrometer. Ion mass/charge (m/z) ratios are reported as values in atomic mass units.

Semi-preparative purification of radiolabelled material was performed on a Merck-Hitachi L6200A system equipped with Knauer variable wavelength detector and an Eberline radiation detector using a reverse phase column (C18 Phenomenex Gemini, 5 mm, 250x10 mm) and eluting with gradient: 0-5 min 5% aq. MeCN, 5-15 min 5-50% aq. MeCN, 15-30 min 50% aq. MeCN, 30-50 min, 50-90% aq. MeCN, 50-65 min, 65% MeCN at flow rate 5 mL/min. Analytical HPLC samples were analyzed by Agilent HPLC 1100 system equipped with UV multiwavelength detector and Raytest Gabi star radiation detector using reverse phase column (ACE 111-0546, C18, 3 mm, 50x4.6 mm) and eluting with 45% aq. MeCN at flow rate 1 mL/min. Samples for PBS, plasma and microsome stability were analyzed by Waters ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLCTM) system equipped with Berthold coincidence detector (FlowStar LB513) using UPLC column (Waters Acquity BEH C18, 1.7 mm, 50x2.1 mm) and eluting with gradient 0-70% aq. MeCN over 5 min at flow 0.7 mL/min or for microsome assay with 30% aq. MeCN over 5 min at flow 0.7 mL/min.

Bovine serum albumin was purchased from Acros Organics. Pooled human liver microsomes, pooled liver microsomes from male Spargue Dawley rats (20 mg protein per mL) and NADPH regenerating system (A: 31 mM NADP+, 66 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 66 mM MgCl2; B: 40 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) were obtained from BD Biosciences. Male Wistar rats were obtained from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). Animal care and all experimental procedures were approved by the Cantonal Veterinary Office in Zurich, Switzerland. The animals were allowed free access to food and water.

Radiosynthesis

(E)-3-(Pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone O-(2-(3-18F-fluoropropoxy)ethyl) oxime ([18F]-PSS223): No-carrier-added [18F]-fluoride was produced via nuclear 18O(p, n)18F reaction from enriched 18O-water using IBA cyclone 18/9 cyclotron and it was immediately trapped on a QMA cartridge (preconditioned with 0.5 M aq. K2CO3 (1x5 mL), then H2O (1x5 mL) and dried in air). The trapped [18F]-fluoride was eluted from the cartridge with 0.25% wt Kryptofix-222® solution (1 mL) in basic (0.05% wt K2CO3) aq MeCN (75% vv) into a tightly closed reaction vial. The solvents were evaporated in vacuo (130 mbar) with gentle stream of N2 gas at 110 °C over 5 min. To the resulting solid residue anhydrous MeCN (1 mL) was then added and the mixture was azeotropically dried in vacuo (130 mbar) with gentle stream of N2 at 110 °C. To the dried Kryptofix-222®/[18F–] complex a solution of (E)-3-(2-(((3-(pyridin-2-ylethynyl)cyclohex-2-en-1-ylidene)amino)oxy)ethoxy)propyl methanesulfonate (2.44 mg, 6.22 μmol) in anhydrous N,N`-dimethylformamide (0.3 mL) was added and the dark brown mixture was heated at 90 °C for 10 min. The crude mixture was diluted with 50% vv aq. MeCN (2 mL) and purified via semi-preparative HPLC. The desired product was collected (retention time: 31.9 min) and immediately diluted with H2O (10 mL). The aqueous solution was passed through a C18 cartridge (preconditioned with EtOH (1x5 mL), then H2O (1x5 mL) and dried in air) and the cartridge was washed with H2O (2x1 mL) and the product was eluted from the C18 cartridge with EtOH (1x0.3 mL) in a sterile vial containing 50% aq. PEG200 (5 mL) to afford the radiolabelled title compound in 20% decay corrected yield. Typically starting from ca. 30 GBq of activity, 5-6 GBq of product was obtained. The radiochemical purity was >97% and specific activity in the range of 100-320 GBq/mmol.

Determination of logD

For purposes of logD determination a further product elution from the C18 cartridge was carried out using EtOH (0.3 mL) and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo (100 mbar) at 90 °C for 5 min.

The determination of logD value was performed using the shake-flask method as previously reported [28,35]. [18F]-PSS223 (453 MBq) was partitioned between phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) saturated with 1-octanol (2 mL) and 1-octanol saturated with phosphate (pH 7.4) buffer (2 mL). The octanol (top) phase (0.5 mL) was washed with phosphate (pH 7.4) buffer saturated with 1-octanol (2x0.5 mL). The purity of the material (14 MBq) was confirmed by HPLC analysis. Finally washed octanol phase (0.1 mL) was diluted with phosphate (pH 7.4) buffer saturated with 1-octanol (0.1 mL) and the two phases were shaken and radioactivity in each phase was measured in a γ-counter.

Pharmacology

Competition Binding Assay

Brain membranes were prepared from Sprague Dawley rat brains as described previously [28]. Frozen membranes were thawed on ice and pelleted at 45000xg at 4 °C for 5 min. The membranes were washed twice with HEPES buffer (30 mM HEPES, 110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, pH 8 at 4°C) and resuspended in HEPES buffer at a protein concentration of 1.3 mg/mL. The binding assay was performed as previously described [28]. In brief, brain membranes (0.1 mg protein) were incubated in triplicates at ambient temperature with 2 nM [3H]ABP688 and PSS223 at concentrations between 10 pM and 100 μM in a total volume of 0.2 ml HEPES. PSS223 was diluted from a 1 mM ethanolic (50%) solution. The corresponding EtOH concentrations did not affect [3H]ABP688 binding (data not shown). Unspecific binding of [3H]ABP688 was estimated with 100 μM MMPEP. After 45 min, the samples were filtrated and the filters containing the membranes with bound [3H]ABP688 were measured in a β-counter (Beckman LS6500). Bound [3H]ABP688 (B, pmol per mg protein) was fitted with Excel solver to Equation 1 to estimate IC50.

where C is the total PSS223 concentration, Bmax is the maximal B, i.e., the plateau in the B/C plot at low log C and Bmin is the minimal B, i.e., the plateau at high log C. The inhibition constant Ki of PSS223 was estimated from IC50 and Kd of ABP688 (1.7±0.2 nM) [18] with the Cheng-Prusoff equation.

Saturation Binding Assay

Brain membranes were incubated with [18F]-PSS223 at concentrations between 0.25 and 100 nM as described above. Unspecific binding was determined with 100 μM MMPEP. After filtration, bound [18F]-PSS223 was quantified in a g-counter (PerkinElmer, Wizard) and Kd was estimated according to Equation 2,

where Bspec is the difference between B and the unspecific binding (at 100 μM MMPEP) and Cu is the unbound concentration, i.e. the difference between the total and the bound concentrations. Bmax,spec is the maximal Bspec at receptor saturation. Three independent experiments were performed with [18F]-PSS223 obtained from three independent radiolabelling productions.

In vitro autoradiography

Frozen horizontal brain slices (20 mm) from a male Wistar rat (492 g) adsorbed to SuperFrost Plus slides were thawed at ambient temperature and preincubated on ice for 10 min in HEPES buffer (see above) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Excess solution was carefully removed and slides were incubated with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 alone or together with 100 nM ABP688 or 100 nM JNJ16259685 in HEPES buffer for 45 min at ambient temperature. After incubation, the solutions were decanted and the slides washed on ice in HEPES buffer containing 0.1% BSA, and twice in HEPES buffer (3 minutes each) and finally dipped in H2O. Dried slides were exposed to a phosphor imager plate for 30 min and the plate was scanned in a BAS5000 reader (Fuji).

Stability in PBS and plasma

[18F]-PSS223 (7-8 MBq) was incubated in phosphate buffer (4 mM KH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) or rat plasma at 37 °C for up to 2 h. At different time points, samples were diluted and enzymatic reactions stopped with ice cold MeCN (140 mL). Plasma samples were centrifuged at 12000xg for 10 min. The samples were filtered and supernatants were analyzed by UPLC.

Microsome stability assay

[18F]-PSS223 (15 MBq) was preincubated for 5 min at 37 °C with 50 mL NADPH regenerating system A, 10 mL NADPH regenerating system B, 200 mL phosphate buffer (0.5 M, pH 7.4) and H2O in a total volume of 975 mL. Rat or human liver microsomes (25 mL) were added at a final protein concentration of 0.5 mg/mL at time 0. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C at 600 rpm and 100 mL aliquots were removed at the indicated time points and immediately quenched with the same volume of ice-cold MeCN. Proteins were precipitated at 12000xg (3 min) and the supernatants were filtered and analyzed by UPLC. NADPH regenerating system and microsomes were replaced by water, respectively in two control experiments.

PET scans

Rats were immobilized by anaesthesia with 2-3% isoflurane in oxygen/air on a GE Vista explore PET/CT scanner with the head in the field of view. Body temperature was controlled with a rectal probe connected to a 37 °C air blower and respiratory frequency was monitored with a 1025T Small Animal Monitoring and Gating System from SA Instruments (Sony Brook, NY, USA). At the start of data acquisition 15-30 MBq [18F]-PSS223 or [11C]-ABP688 was injected into a tail vein and data were collected in list mode for 90 and 60 min, respectively. After the PET scan, a CT was performed for anatomical orientation. PET data were reconstructed with 2D ordered subset expectation maximization (2D OSEM) and analyzed with PMOD 3.2 (PMOD, Zurich, Switzerland).

Results

Synthesis and radiolabelling

The syntheses of the cold reference compound PSS223 and the desired radiolabelled analogue were accomplished via key intermediate 8 which was envisioned to originate from oxime 5 via SN2 reaction with bromoether 4. Oxime 5 was prepared by a Sonogashira reaction [36] using commercially available 2-bromopyridine and (E)-3-ethynylcyclohex-2-enone oxime as previously reported [33] (Supporting data).

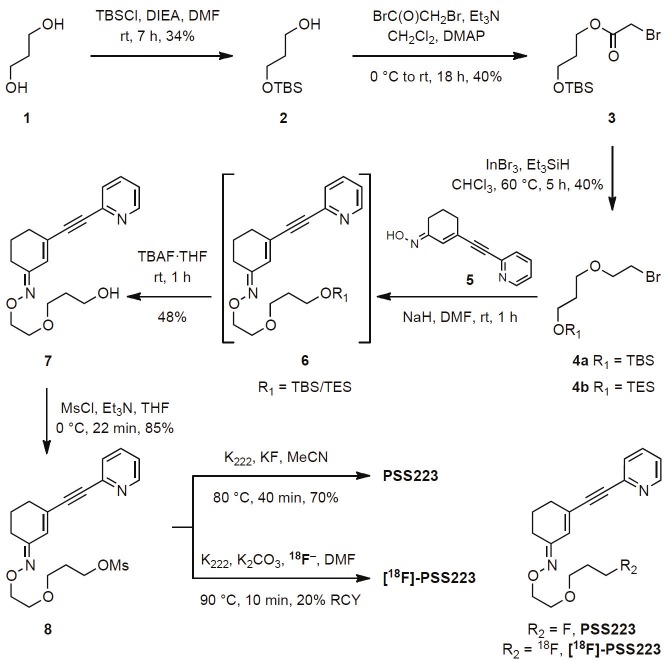

Monoprotection of commercially available propanediol with TBSCl, followed by esterification of the free hydroxyl group afforded ester 3 in 40% yield. Ester 3 was then reduced to the corresponding ether with triethylsilane [37] in a reaction catalyzed by indium(III)-bromide (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Syntheses of PSS223 and [18F]-PSS223 from key intermediate 8 via SN2 reaction.

Bromoethers 4a and 4b were reacted with oxime 5 to afford alcohol 7 after deprotection of silyl ethers with TBAF in 48% yield. Finally, mesylation of 7 afforded the desired precursor 8 which was used for the syntheses of PSS223 and [18F]-PSS223 (Figure 2). In the presence of Kryptofix-222®, nucleophilic substitution of mesylate 8 with potassium fluoride gave reference compound PSS223 in 70% yield. Under analogous conditions [18F]-PSS223 was obtained in 20% radiochemical decay corrected yield. The identity of [18F]-PSS223 was confirmed by HPLC analysis via co-injection with cold PSS223.

In vitro evaluation

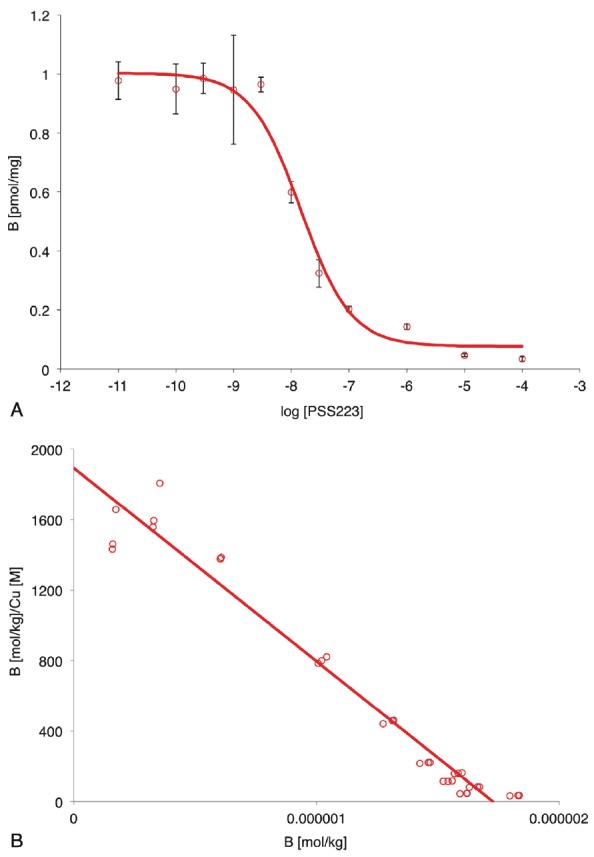

The experimentally determined logDpH7.4 of [18F]-PSS223 was 1.89±0.05. The binding affinity of PSS223 was first estimated from a single competition binding experiment with 2 nM [3H]-ABP688 (Figure 3A). The estimated IC50 value was 14 nM and the respective Ki value amounted to 6 nM. The maximal displacement of [3H]-ABP688 by PSS223 was similar as observed with 100 μM MMPEP, i.e., about 96% of total binding. Next, we determined Kd of [18F]-PSS223 in a saturation binding assay. Nonlinear curve fitting of three independent experiments revealed a Kd of 3.34±2.05 nM and Bmax ranging from 2 to 6 pmol/mg. Linearization in the Scatchard plot confirmed a single binding site (Figure 3B). Non-specific binding was estimated with an excess of MMPEP [38,39].

Figure 3.

A. Displacement of [3H]-ABP688 by PSS223. [3H]-ABP688 (total 2 nM) binding (B) as a function of the PSS223 concentration. Symbols represent mean±SD of one experiment performed in triplicate. Non-linear fitting (red line) resulted in IC50 14 nM and corresponding Ki 6 nM; B. Scatchard plot analysis of the specific binding of [18F]-PSS223 to rat brain membranes. Symbols, specific binding (total binding minus binding in the presence of 100 μM MMPEP) of one representative experiment; red line, linear regression.

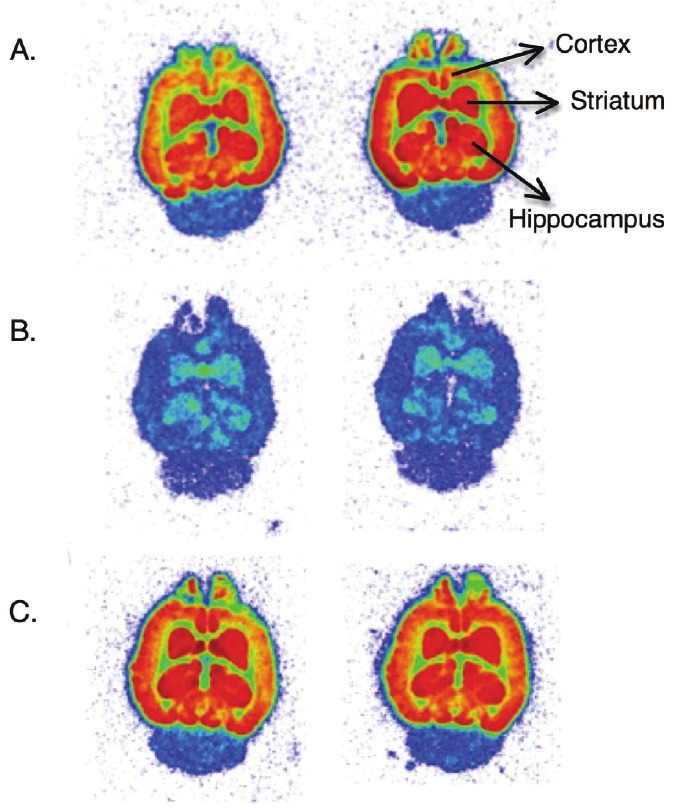

In vitro autoradiography with rat brain slices showed heterogeneous radioactivity distribution after incubation with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 (Figure 4A). Highest radioactivity was observed in striatum, hippocampus and cortex, regions known to express high levels of mGluR5 [40-42]. As expected from low mGluR5 expression in cerebellum [5], binding to this brain region was negligible. Figure 4B shows the displacement of [18F]-PSS223 with an excess of ABP688, confirming the specificity of [18F]-PSS223 for mGluR5. To demonstrate selectivity of [18F]-PSS223 for mGluR5 over mGluR1, the receptor with closest sequence similarity to mGluR5, brain slices were incubated with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 and an excess of the mGluR1 antagonist JNJ16259685 (Figure 4C). Binding competition was not observed in this case, confirming the selectivity of [18F]-PSS223 for mGluR5.

Figure 4.

In vitro autoradiography with rat brain slices. A. Incubation with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 showing heterogeneous distribution with highest expression in striatum, hippocampus and cortex; B. Brain slices incubated with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 and 100 nM ABP688; C. Brain slices incubated with 1 nM [18F]-PSS223 and 100 nM mGluR1 antagonist JNJ16259685. Blue, green, orange, red, dark red indicate radioactivity from low to high. Columns represent same experiment performed in duplicate.

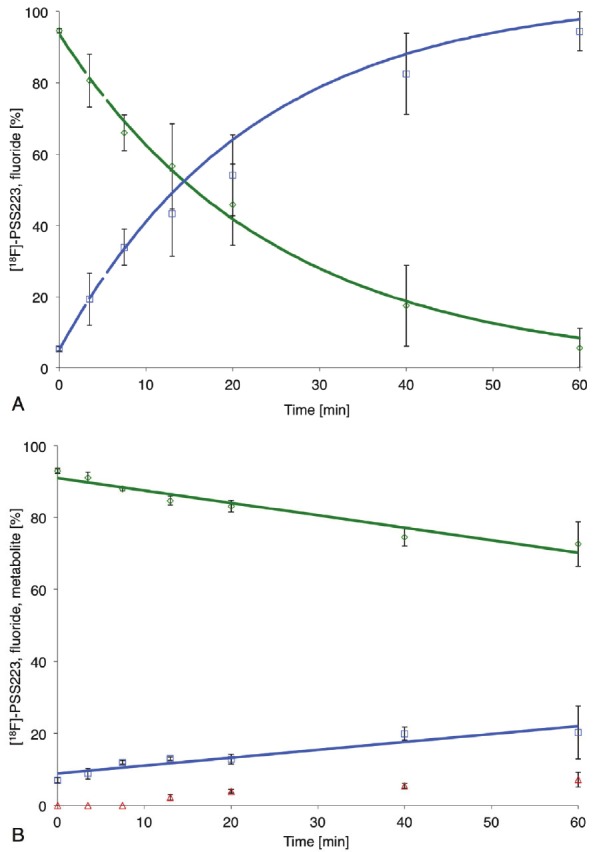

[18F]-PSS223 was stable over 120 minutes in phosphate buffer and rat plasma at 37 °C. However, incubation with rat liver microsomes and NADPH under aerobic conditions resulted in a significant decrease of [18F]-PSS223 and the appearance of a polar radiometabolite, co-eluting with co-injected [18F]-fluoride. After one hour, about 90% of [18F]-PSS223 was metabolized under the chosen experimental conditions (Figure 5A). Incubation of [18F]-PSS223 with human liver microsomes under otherwise analogous conditions resulted in 20% decrease of [18F]-PSS223 after one hour (Figure 5B) and the generation of two polar radiometabolites, the more polar one co-eluting with [18F]-fluoride. None of the polar compounds were detected in the absence of microsomes or NADPH.

Figure 5.

A. Metabolism of [18F]-PSS223 by rat liver microsomes. Green symbols, [18F]-PSS223; blue symbols, polar 18F-radiometabolite; lines, fitted exponential functions; B. Metabolism of [18F]-PSS223 by human liver microsomes. Green symbols, [18F]-PSS223; blue and red symbols, polar 18F-radiometabolites.

In vivo evaluation

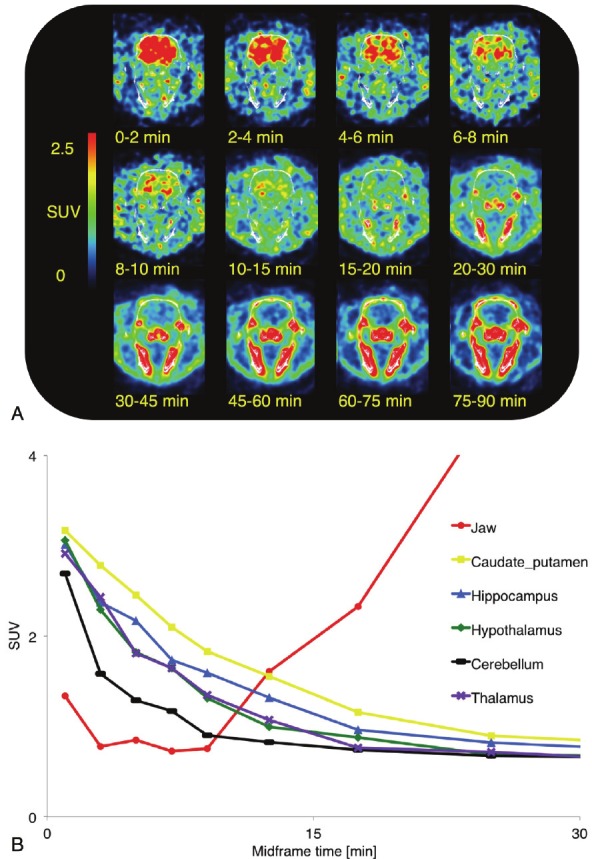

Dynamic PET scans were performed with two rats to determine whether [18F]-PSS223 could be used to image brain regions expressing mGluR5. Figure 6A shows a transversal plane across the head region over time. In the early time frames, brain perfusion resulted in high homogenous radioactivity in the brain. This was followed by a rapid washout from all brain regions and radioactivity accumulation in the skull and jaws. The time activity curves of mGluR5-rich brain regions and cerebellum show accumulation of [18F]-PSS223 in striatum, hippocampus and cortex (Figure 6B). However, the mean residence time was relatively short and radioactivity approached cerebellum levels already after about 20 minutes. High accumulation of 18F-radioactivity in bone is demonstrated by the time activity curve of the jaws.

Figure 6.

A. PET dynamic scan of the head of a male Wistar rat injected with [18F]-PSS223. Transverse planes through the head summarized for the indicated time windows. White, CT; B. Time activity curves of [18F]-PSS223 uptake in a male Wistar rat in different brain regions showing increasing uptake in jaw due to rapid defluorination.

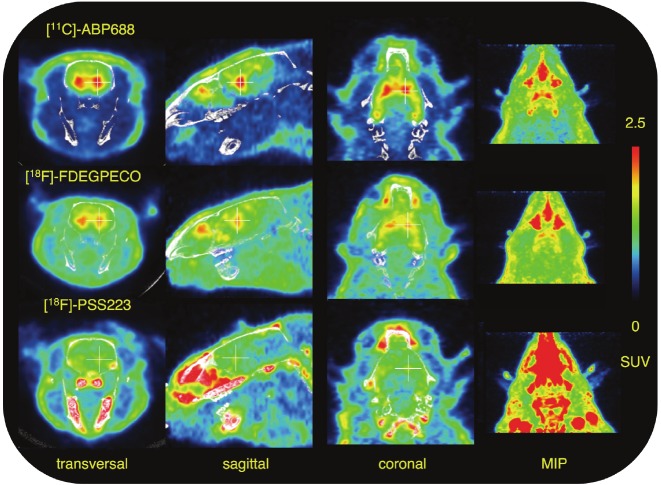

Figure 7 shows a comparison of PET scans with [11C]-ABP688, [18F]-FDEGPECO and [18F]-PSS223, all averaged from 2 to 45 min after tracer injection. [18F]-PSS223 data are from the same scan shown in Figures 6A and B. The [18F]-FDEGPECO image was reconstructed from the data shown in our recent publication [29,43]. Comparing the three tracers, [11C]-ABP688 showed the highest relative radioactivity accumulation in mGluR5-rich brain regions such as hippocampus and striatum. [18F]-FDEGPECO also allows visualization of mGluR5-rich regions in the brain, however, at a higher background radioactivity. Our newest derivative, [18F]-PSS223 shows only weak accumulation in mGluR5-rich brain regions and significant accumulation of radioactivity in the skull and jaws as a result of rapid defluorination.

Figure 7.

Rat brain PET images of [11C]-ABP688, [18F]-FDEGPECO and [18F]-PSS223. Planes (crosshairs) and maximal intensity projections (MIP) averaged from 2 to 45 min after tracer injection.

Discussion

Reference compound PSS223 was prepared in an overall satisfactory yield and all compounds en route were fully characterized (NMR, IR, MS). The synthesis of bromoether 4 proved to be more challenging than initially anticipated. After several unsuccessful attempts to obtain compound 4 via direct functionalization with dihaloethane, an alternative approach was employed and yielded the desired bromoether 4 in 5% overall yield from three steps. During the reduction of the ester functionality in 3, the TBS silyl ether was partially substituted by the TES group (originating from the reagent triethylsilane) to afford a mixture of TBS:TES silylethers in a ratio of 2:1 (4a:4b, Figure 2). For our purposes, it was not necessary to separate the silyl ethers 4a and 4b since they were removed to afford free hydroxyl group in the following step.

The radiosynthesis of [18F]-PSS223 was accomplished in a single step from mesylate precursor 8 reproducibly in a good radiochemical yield. Pure radiotracer was obtained after HPLC semipreparative purification in a total radiosynthesis time of 90 min (from the end of bombardment). Experimentally determined logD value of [18F]-PSS223 was 0.2 log units higher than that of [18F]-FDEGPECO (1.7±0.1) [28] and 0.5 log units lower than that of [11C]-ABP688 [18]. This was within the optimal lipophilicity range of high affinity ABP688 analogues, (i.e., ClogP value below 2.5 and logP between 0.9 and 2.5, range of values desired for fast blood-brain barrier passage) [32]. One may assume that for those ABP688 analogues logDpH7.4 corresponds to logP as both the pyridine and the oxime nitrogen atoms are non-protonated at pH 7.4.

[18F]-PSS223 exhibited similarly high affinity for the mGluR5 as [11C]-ABP688, i.e., 3.3 nM compared to 1.7 nM [18], suggesting that the long chain in [18F]-PSS223 did not significantly affect the binding affinity. The value of Bmax determined for [18F]-PSS223 (range: 2-6 pmol/mg) compared favourably to the Bmax values of [11C]-ABP688 (231±18 fmol/mg) [18] and [18F]-FDEGPECO (range: 0.5-4 pmol/mg) [28]. Specific binding of [18F]-PSS223 to mGluR5-rich brain regions in the in vitro autoradiography experiments prompted further in vitro and in vivo characterization of [18F]-PSS223.

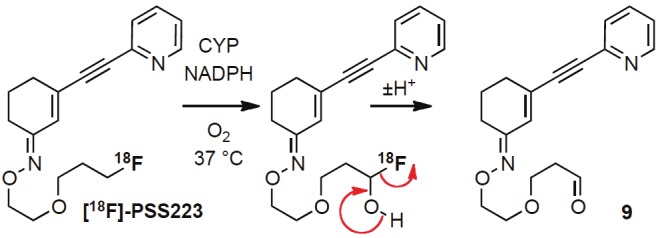

[18F]-PSS223 was stable in buffer and rat plasma; however, it was significantly metabolized by the rat liver microsomal enzymes and a polar radiometabolite co-eluting with [18F]-fluoride was observed by UPLC. In the experiments with human liver microsomes, two polar radiometabolites were detected albeit in the amounts significantly lower than those observed with rat microsomal enzymes. Based on the control experiments, it was concluded that the process was NADPH-dependent, implying the involvement of oxidoreductases. One likely mechanism involves defluorination preceded by the oxygenation of the carbon atom in the α-position to the fluorine atom [44]. The possible mechanism is depicted in Figure 8. A lower degree of metabolic activity of the human compared to that of rat liver microsomes would be in agreement with several other studies [45-48]. Considering the rapid metabolism in vitro and the possibility of defluorination in vivo, we performed two dynamic PET scans. PET analysis demonstrated rapid wash-out of radioactivity from the brain and high accumulation in the skull and jaws. Accumulation of [18F]-PSS223 in mGluR5-rich brain regions was significantly lower than observed for [18F]-FDEGPECO. [18F]-PSS223 was therefore, not further investigated in vivo. The observed radioactivity accumulation in bone supports the conclusion that the radiometabolite (or one of the radiometabolites) observed with liver microsomes was [18F]-fluoride. Based on the higher stability of [18F]-PSS223 in human liver microsomes, less extensive defluorination is expected in humans.

Figure 8.

Likely mechanism of defluorination of [18F]-PSS223 involves cytochrome P450-catalyzed C-oxygenation. The aldehyde 9 is oxidized or reduced to the respective carboxylic acid or alcohol while [18F]-fluoride is accumulated in bone.

The difference in the in vivo behaviour between [18F]-PSS223 and [18F]-FDEGPECO could be attributed to the β-heteroatom effect [49,50], by which primary aliphatic 18F-atoms in a β-position to heteroatom (e.g., [18F]-FCH2CH2OR) are found to be metabolized at a slower rate. This rationale supports absence of defluorination for [18F]-FDEGPECO.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the radiosynthesis of [18F]-PSS223 was accomplished in good radiochemical yields and high specific radioactivity. The new radioligand binds mGluR5 in vitro with low nanomolar affinity and shows heterogeneous and specific accumulation in vitro in mGluR5-rich brain regions in autoradiographic studies. Although the PET studies with [18F]-PSS223 did not allow a clear-cut visualization of mGluR5 in vivo in the rat brain, due to low metabolic stability and rapid wash-out, [18F]-PSS223 could potentially find utility in higher animals considering that [18F]-PSS223 exhibited higher stability in human microsomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mrs. Claudia Keller and Mrs. Petra Wirth for performing the PET scans. Mr. Bruno Mancosu is acknowledged for technical assistance with 11C-module. Prof. P. A. Schubiger, Mrs. Cindy Fischer and Dr. Thomas Betzel are acknowledged for support and many fruitful discussions.

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all compounds, and HPLC chromatographs of [18F]-PSS223 are provided.

Disclaimer of conflict of interest

none.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular imaging with PET. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Dewey SL. PET and drug research and development. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1154–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowden L. Fluoroamino acids and protein synthesis. Ciba Foundation Symposium, Carbon-Fluorine Compounds. 1972;2:141–159. doi: 10.1002/9780470719855.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weygand F, Oettmeier W. Fluorine-containing amino acids. Russian Chem Rev. 1970;39:290–300. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masu M, Tanabe Y, Tsuchida K, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. Sequence and expression of a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 1991;349:760–765. doi: 10.1038/349760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pin JP, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors - structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanabe Y, Masu M, Ishii T, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. A family of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90118-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu YM, Jia Z, Janus C, Henderson JT, Gerlai R, Wojtowicz JM, Roder JC. Mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 show impaired learning and reduced CA1 long-term potentiation (LTP) but normal CA3 LTP. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5196–5205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05196.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiamulera C, Epping-Jordan MP, Zocchi A, Marcon C, Cottiny CC, Tacconi S, Corsi M, Orzi F, Conquet FO. Reinforcing and locomotor stimulat effects of cocaine are absent in mGluR5 null mutant mice. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:873–874. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daggett LP, Sacaan AI, Akong M, Rao SP, Hess SD, Liaw C, Urrutia A, Jachec C, Ellis SB, Dreessen J, Knopfel T, Landwehrmeyer GB, Testa CM, Young AB, Varney M, Johnson EC, Velicelebi G. Molecular and functional characterization of recombinant human metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:871–886. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00085-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorri F, Hampson DR, Baskys A, Wojtowicz JM. Down-regulation of mGluR5 by antisense deoxynucleotides alters pharmacological responses to application of ACPD in the rat hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 1997;147:48–54. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohnuma T, Augood SJ, arai H, McKenna PJ, Emson PC. Expression of the human excitatory amino acid transporter 2 and metabotropic glutamate receptors 3 and 5 in the prefrontal cortex from normal individuals and patients with schizophrenia. Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouse ST, Marino MJ, Bradley SR, Awad H, Wittmann M, Conn PJ. Distribution and roles of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the basal ganglia motor circuit: implications for treatment of Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88:427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu L, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Radioligands for the PET imaging of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1558–1568. doi: 10.2174/156802610793176783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasparini F, Lingenhohl K, Stoehr N, Flor PJ, Heinrich M, Vranesic I, Biollaz M, Allgeier H, Heckendorn R, Urwyler S, Varney MA, Johnson EC, Hess SD, Rao SP, Sacaan AI, Santori EM, Velicelebi G, Kuhn R. 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), a potent, selective and systemically active mGluR5 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritzen A, Mathiesen JM, Thomsen C. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic prospects of metabotropic glutamate receptor allosteric modulators. Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2005;97:202–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ametamey SM, Kessler LJ, Honer M, Wyss MT, Buck A, Hintermann S, Auberson YP, Gasparini F, Schubiger PA. Radiosynthesis and preclinical evaluation of 11C-ABP688 as a probe for imaging the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ametamey SM, Treyer V, Streffer J, Wyss MT, Schmidt M, Blagoev M, Hintermann S, Auberson Y, Gasparini F, Fischer UC, Buck A. Human PET studies of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 with 11C-ABP688. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown AK, Kimura Y, Zoghbi SS, Simeon FG, Liow JS, Kreisl WC, Taku A, Fujita M, Pike VW, Innis RB. Metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptors are quantified in the human brain with a novel radioligand for PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:2042–2048. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shetty HU, Zoghbi SS, Simeon FG, Liow JS, Brown AK, Kannan P, Innis RB, Pike VW. Radiodefluorination of 3-fluoro-5-(2-(2-[18F] (fluoromethyl)-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl)benzonitrile ([18F] SP203), a radioligand for imaging brain metabotropic glutamate subtype-5 receptors with positron emission tomography, occurs by glutathionylation in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:727–735. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simeon FG, Brown AK, Zoghbi SS, Patterson VM, Innis RB, Pike VW. Synthesis and simple 18F-radiolabelling of 3-fluoro-5-(2-(2-fluoromethyl)thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl)benzonitrile as a high affinity radioligand for imaging monkey brain metabotropic glutamate subtype-5 receptors with positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3256–3266. doi: 10.1021/jm0701268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barret O, Tamagnan G, Batis J, Jennings D, Zubal G, Russell D, Marek K, Seibyl J. Quantitation of glutamate mGluR5 receptor with 18F-FPEB PET in humans. J Nucl Med Meet Abstr. 2010;51:215. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamill TG, Krause SRC, Bonnefous C, Govek S, Seiders TG, Cosford NPD, Roppe J, Kamenecka T, Patel S, Gibson RE, Sanabria S, Riffel K, Eng W, King C, Yang X, Green MD, O'Malley SS, Hargreaves R, Burns HD. Synthesis, characterization, and first successful monkey imaging studies of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) PET radiotracers. Synapse. 2005;56:205–216. doi: 10.1002/syn.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JQ, Tueckmantel W, Zhu A, Pellegrino D, Brownell AL. Synthesis and preliminary bilogical evaluation of 3-[18F] fluoro-5-(2-pyridinylethynyl)benzonitrile as a PET radiotracer for imaging metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Synapse. 2007;61:951–961. doi: 10.1002/syn.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumann CA, Mu L, Wertli N, Kramer SD, Honer M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Syntheses and pharmacological charazterization of novel thiazole derivatives as potential mGluR5 PET ligands. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:6044–6054. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honer M, Stoffel A, Kessler LJ, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Radiolabeling and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of [18F]-FE-DABP688 as a PET radioligand for the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumann CA, Mu L, Johannsen S, Honer M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Structure-activity relationships of fluorinated (E)-3-((6-methylpyridin-2-yl)ethynyl)cyclohex-2-enone-O-methyloxime (ABP688) derivatives and the discovery of a high affinity analogue as a potential candidate for imaging metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) with positron emission tomography (PET) J Med Chem. 2010;53:4009–4017. doi: 10.1021/jm901850k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanger-Baumann CA, Mu L, Honer M, Belli S, Alf MF, Schubiger PA, Kramer SD, Ametamey SM. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of [18F]-FDEGPECO as a PET tracer for imaging the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) Neuroimage. 2011;56:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs AH, Li H, Winkeler A, Hilker R, Knoess C, Ruger A, Galldiks N, Schaller B, Sobesky J, Kracht L, Monfared P, Klein M, Vollmar S, Bauer B, Wagner R, Graf R, Wienhard K, Herholz K, Heiss WD. PET-based molecular imaging in neuroscience. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1051–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reichel A. Addressing central nervous system (CNS) penetration in drug discovery: basics and implications of the evolving new concept. Chem Biodivers. 2009;6:2030–2049. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dischino DD, Welch MJ, Kilbourn MR, Raichle ME. Relationship between lipophilicity and brain extraction of C-11-labeled radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:1030–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucatelli C, Honer M, Salazar JF, Ross TL, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Synthesis, radiolabeling, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of [18F]-FPECMO as a positron emission tomography radioligand for imaging the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:613–622. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasparini F, Auberson Y, Kessler L, Ametamey SM. A preparation of pyridylacetylene derivatives, useful as radiotracers and imaging agents. WO 2005030723 A1 2005; [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson AA, Jin L, Garcia A, DaSilva JN, Houle S. An admonition when measuring the lipophilicity of radiotracers using counting techniques. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2001;54:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Convenient synthesis of acetylenes - catalytic substitutions of acetylenic hydrogen with bromoalkenes, iodoarenes and bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;50:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakai N, Moriya T, Fujii K, Konakahara T. Direct reduction of esters to ethers with an indium(III)bromide/triethylsilane catalytic system. Synthesis. 2008;21:3533–3536. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cosford NDP, Tehrani L, Roppe J, Schweiger E, Smith ND, Anderson J, Bristow L, Brodkin J, Jiang XH, McDonald I, Rao S, Washburn M, Varney MA. 3-[(2-Methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl] -pyridine: a potent and highly selective metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptor antagonist with anxiolytic activity. J Med Chem. 2003;46:204–206. doi: 10.1021/jm025570j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagano A, Ruegg D, Litschig S, Stoehr N, Stierlin C, Heinrich M, Floersheim P, Prezeau L, Carroll F, Pin JP, Cambria A, Vranesic I, Flor PJ, Gasparini F, Kuhn R. The non-competitive antagonists 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine and 7-hydroxyiminocyclopropan[b] chromen-1a-carboxylic acid ethyl ester interact with overlapping binding pockets in the transmembrane region of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Bio Chem. 2001;275:33750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shigemoto R, Mizuno N. Metabotropic glutamate receptors - immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization analysis. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2000;18:63–98. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shigemoto R, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Sugihara H, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wanger-Baumann CA. Development of novel fluorine-18 labelled PET tracers for imaging of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) PhD Thesis. 2010 DISS. ETH 18915. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Testa B, Kramer SD. The biochemistry of drug metabolism - An introduction: Part 2. Redox reactions and their enzymes. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:257–405. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berthou F, Guillois B, Riche C, Dreano Y, Jacqzaigrain E, Beaune PH. Interspecies variations in caffeine metabolism related to cytochrome P4501A enzymes. Xenobiotica. 1992;22:671–680. doi: 10.3109/00498259209053129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearce R, Greenway D, Parkinson A. Species differences and interindividual variation in liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2A enzymes: Effects on coumarin, dicumarol, and testosterone oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90115-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ratanasavanh D, Lamiable D, Biour M, Guedes Y, Gersverg M, Leutenegger E, Riche C. Metabolism and toxicity of coumarin on cultured human, rat, mouse and rabbit hepatocytes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1996;10:504–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kramer SD, Testa B. The biochemistry of drug metabolism - An introduction: Part 6. Inter-individual factors affecting drug mtabolism. Chem Biodivers. 2008;5:2465–2578. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.French AN, Napolitano E, Brocklin HFV, Brodack JW, Hanson RN, Welch MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA. The beta-heteroatom effect in metabolic defluorination: The interaction of resonance and inductive effects may be a fundamental determinant in the metabolic liability of fluorine-substituted compounds. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1991;30:431–433. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purohit A, Radeke H, Azure M, Hanson K, Benetti R, Su F, Yalamanshili P, Yu M, Hayes M, Guaraldi M, Kagan M, Robinson S, Casebier D. Synthesis and biological evaluation of pyridazinone analogues as potential cardiac positron emission tomography tracers. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2954–2970. doi: 10.1021/jm701443n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.