Abstract

This study aimed to identify barriers and facilitators of mental health care for patients with trauma histories via qualitative methods with clinicians and administrators from primary care clinics for the underserved. Individual interviews were conducted, followed by a combined focus group with administrators from three jurisdictions; there were three focus groups with clinicians from each clinic system. Common themes were identified, and responses from groups were compared. Administrators and clinicians report extensive trauma histories among patients. Clinician barriers include lack of time, patient resistance, and inadequate referral options; administrators cite reimbursement issues, staff training, and lack of clarity about the term trauma. A key facilitator is doctor-patient relationship. There were differences in perceived barriers and facilitators at the institutional and clinical levels for mental health care for patients with trauma. Importantly, there is agreement about better access to and development of trauma-specific interventions. Findings will aid the development and implementation of trauma-focused interventions embedded in primary care.

Keywords: Trauma, primary care, barriers to care, mental health interventions, low-income minorities

Provision of primary health care to low-income minority populations can be complex and challenging. Addressing mental health problems adds to this difficulty, yet primary care settings are the preferred location for seeking mental health care for many minority and low-income patients (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). A number of integrated models of providing mental health care in coordination with primary care, particularly for depression, have been developed (Gilbody et al., 2003). Many represent collaborative care interventions that involve quality improvement efforts and active outreach to depressed patients by nurses or health promoters. In contrast, interventions that are specific to trauma-related mental health problems in primary care are less developed (Meredith et al., 2009), even though primary care clinicians recognize the need for trauma-specific interventions and are interested in finding ways to more effectively treat these problems (Green et al., 2011).

Trauma exposure is common among low-income uninsured primary care patients (McCauley et al., 1997; Medrano et al., 2004) and has been shown to have negative mental health effects, including anxiety, depression, and interpersonal problems (Green, 1994; Roth et al., 1997; Weaver and Clum, 1995), as well as negative physical health effects (Friedman and Schnurr, 1995; Green and Kimerling, 2004; Schnurr and Green, 2004) and disability (Seng et al., 2006). A study of low-income female patients in family planning and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children clinics found lifetime exposure to at least one traumatic event in more than 90% of the sample. Half had experienced domestic violence, and more than one third had been raped and/or experienced childhood abuse (Green et al., 2006; Miranda et al., 2003, 2006). Trauma exposure is associated with decreased routine or preventive health care (Farley et al., 2001; Rheingold et al., 2004; Robohm and Buttenheim, 1996). In addition, the negative health sequelae of trauma exposure are tied to substantial health care system costs (Walker et al., 1999, 2003).

Despite the high prevalence of trauma and its negative health and health system costs, patients and clinicians do not regularly address trauma and abuse issues during primary care encounters. A study of abused women found that 86% of them had seen their regular health care provider in the past year but only one in three had discussed abuse with them (McCauley et al., 1997). Given that primary care is often the only source of health care for many low-income patients, this important aspect of patients’ histories with substantial implications for mental health is regularly left unaddressed (Davis et al., 2008). Trauma, often interpersonal in nature, can lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as depression, anxiety disorders such as panic or generalized anxiety, and substance abuse disorders, among others.

Although there are reports of provider perspectives of barriers to mental health care among primary care patients in general, we are interested in trauma-related issues in particular (Cristofalo et al., 2009). The need for trauma-specific interventions is highlighted by a study by Davis et al. (2008), who found that, among urban African-American medical patients with PTSD, only 13.3% had previous trauma-focused treatment. The views and experiences of administrators and clinicians regarding trauma likely contribute to treatment policies and practice patterns within the primary care settings in which they work. The importance of administrator and clinician views is further supported by findings by Meredith et al. (2009) that factors such as level of integration of primary care and mental health services affects provider recognition and management of PTSD.

Study Aims

The primary aim of this study was to describe the barriers and facilitators of appropriate mental health care for trauma-related mental health problems among low-income primary care patients from the perspective of clinicians and administrators. We are interested in whether the “practice ecosystem” in these safety-net settings presents barriers to diagnosis, referral, and treatment of trauma-related problems, with implications for healthcare costs and clinical outcomes. The focus of this work is on trauma-related mental health problems, including PTSD. We used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework to achieve our study aims, with the goal of developing interventions that effectively address trauma-related mental health problems in partnership with community-based safety net primary care settings. CBPR projects often use qualitative methods to gain a better understanding of community views and the problems they intend to address. In that light, focus groups can provide a forum for group discussion and consensus building (Robins et al., 2008).

METHODS

Settings

As part of the work of the National Institute of Mental Health–funded Center for Trauma and the Community at George-town University Medical School, we partnered with three different safety net primary care clinic systems from three different geographic jurisdictions in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area because of variation in the delivery models used to provide primary care and the ethnic composition of the populations served. For example, in one jurisdiction, the health department supports a variety of public-private partnerships that provide health and mental health care for poor and uninsured, mainly immigrant Latinos. In another jurisdiction, a 501(c)(3) private nonprofit agency is the sole contractor for the health department and operates local and federally funded health centers whose largest ethnic group is African-American. The third jurisdiction spans a mix of urban and rural areas with a diverse ethnic mix and has relatively few primary care resources. The opportunity to work with three different systems of primary care could potentially help identify common barriers to care and thus inform the generalizability of our findings. Partnering with three jurisdictions could also help inform the question of whether a single intervention model could be implemented in different care systems or whether differences might require tailoring of interventions.

Study Design

The study used mixed methods, with an emphasis on the collection of qualitative data from focus groups (Robins et al., 2008). The study was organized around two informant levels: a) institutional level, in which one-on-one interviews and a focus group was held with administrators from all three jurisdictions and b) clinical level, in which separate focus groups were held with providers from the three jurisdictions. A unique feature of this study was collection of information from administrators before the administrator-only focus group, with administrator information used to guide the focus group discussion.

Institutional Level

Ten administrators (three to four from each jurisdiction), some of whom also serve as clinicians, were interviewed individually; afterward, a subset of six participants was invited to a focus group. The administrators included chief executive officers/executive directors, medical directors, and program directors from safety-net primary care clinics in the three jurisdictions. Each administrator was interviewed about the organization and composition of primary care services for the low-income and minority population, the organization’s relationship with government/health agencies, barriers and facilitators to primary care among low-income residents, mental health resources and formal connections or coordination of services, relevance of trauma to the care they provide, and their personal history of experiences in collaborating with researchers. Interviews were 1 to 1 and 1/2 hours long, were recorded, and were then transcribed or summarized.

Jurisdiction Summaries

Responses to administrator interviews were used to draft three jurisdiction reports that described the structure of care in their settings. The administrators were then asked to review and edit reports for accuracy and completeness. Their feedback was incorporated into three working reports that were distributed before the focus group. The purpose of this step was to provide interim findings to the administrators and to stimulate discussion in the group about similarities and differences in their systems of care.

Focus Group

Six administrators participated, of whom two were from each jurisdiction and half of whom had some direct patient care responsibilities. The purpose of the focus group was to more specifically discuss trauma among the populations served and possibilities for intervention. The focus group lasted for 90 minutes and was facilitated by two people from the research team; it was videotaped, transcribed, and summarized. The summary was later distributed to participants for review.

Clinical Level

After completion of the administrator focus group, clinicians from the same primary care systems were recruited to participate in focus groups, one for each of the three jurisdictions. The groups were held during times that clinicians normally have staff meetings; therefore, the participants were from different clinic sites within the primary care system. Each group was composed of a mix of clinician types (e.g., physician, nurse practitioner). Administrator focus group participants did not participate in the clinical level focus groups.

Clinician Surveys

Each care provider was surveyed before the focus group on demographic information; professional education; tenure in position; training and duties; examples of psychosocial, mental health, and trauma-related issues seen in their practice (open-ended); their comfort level with these issues (rating as not comfortable, slightly comfortable, comfortable, or very comfortable); and whether they had adequate time to address psychosocial, mental health, and trauma-related issues (three yes/no items).

Focus Groups

We conducted three focus groups, one for each jurisdiction. Each group consisted of five to nine participants and was facilitated by two researchers. The discussion guide for these groups was informed, in large part, by the administrator interviews and focus group previously completed. We structured the discussion to elicit participants’ definitions of trauma without imposing a specific definition to understand how trauma was conceptualized by participants. We therefore began the discussion by asking about provision of mental health care in the setting generally, including types of problems seen and the process for treating them, before asking about trauma-related mental health problems and before eliciting the participants’ own definitions of trauma. This also enabled the participants to express the extent to which they viewed trauma-related issues as distinct from, or overlapping with, other mental health issues.

The clinicians were asked about their experiences with traumatized patients and the possibilities for mental health care provision within the realities of their programs. The group participants were told that their input would be used to help create interventions for provision of trauma-related mental health care in primary care settings for underserved populations, and they were encouraged to provide suggestions for training that would be helpful, as well as suggestions for how researchers should approach this population.

Group sessions were videotaped, and both facilitators reviewed the recordings. Focus group facilitators were researchers trained in qualitative data collection and analysis; a total of five facilitators conducted the groups, with two facilitators conducting two of the three groups. All facilitators were psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, or research psychologists.

Data Analysis

Group facilitators took written notes during the focus groups. These notes and the videotapes were used as the basis for a written summary of each group. One of the two facilitators first wrote a transcription summary based on a review of the videotape and notes, then the second facilitator independently reviewed the videotape and edited the summary. Both group facilitators composed the final summary document and resolved any discrepancies through reference to the videotaped recording.

The summaries of each focus group were separately reviewed by two members of the research team (J. Y. C., L. F.) who identified any statement that had to do with a barrier or facilitator of mental health care. The larger research team then discussed the results of the initial review and reached consensus on the comprehensiveness of the review and whether there were differences between focus groups (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). The findings were then organized by what type of respondent(s) provided the statement(s); administrators (three of six participants) who also performed clinical duties were categorized with the administrator group. Lastly, the research team examined the summary transcripts for trauma-specific themes and exemplary quotes for the themes that were identified.

RESULTS

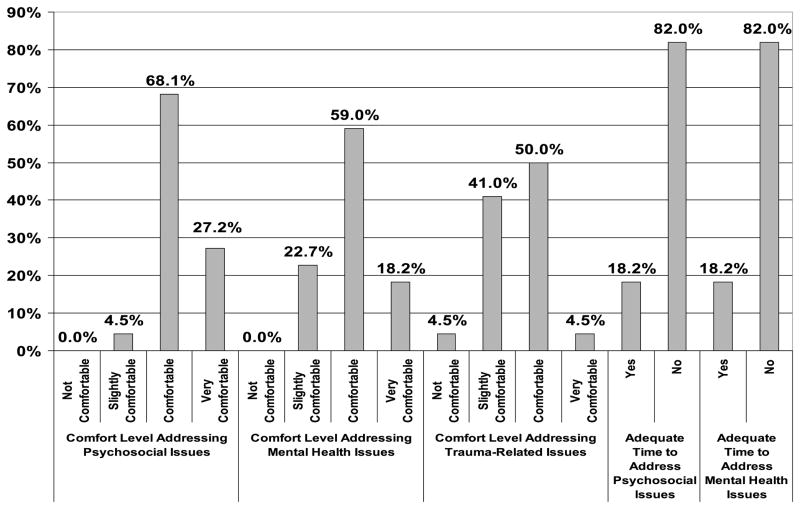

Clinicians included physicians and individuals in nursing sub-specialties (Table 1). Their mean age was 46 ± 10.75 years (range, >31 to 66 years); 50% had been in their current position for less than 2 years, and 32% had been in their current position for more than 5 years. Most (82%) of the clinicians indicated that they did not have adequate time to address either psychosocial or mental health issues with patients. Less than 5% indicated that they are “very comfortable” addressing trauma-related issues; in contrast, 27% and 18% rated themselves as “very comfortable” addressing psychosocial and general mental health issues, respectively (Fig. 1). In open-ended items, the trauma-related issues commonly observed included domestic violence (41%), physical/emotional abuse (27%), rape or sexual abuse (14%), and PTSD (9%).

TABLE 1.

Description of Clinicians

| Characteristic | All Participants (N = 22) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 46.09 (10.75) years |

| Range | 31–66 years |

| Sex | |

| Female | n = 20, 31% |

| Professional degreea | |

| MD/DO/PhD/DDS | n = 15, 69% |

| MPH | n = 2, 9% |

| MSN/FNP/CRNP | n = 7, 32% |

| MBA | n = 1, 5% |

| Job titlea | |

| Physician (staff, primary care, pediatrics) | n = 9, 41% |

| Medical director | n = 5, 23% |

| Executive/clinic director/ administrator | n = 4, 19% |

| Nurse: Midwife/case manager/ practitioner/administrator | n = 8, 38% |

| Time in current position | |

| <1 yr | n = 3, 14% |

| 1–2 yrs | n = 8, 36% |

| 3–4 yrs | n = 4, 18% |

| >5 yrs | n = 7, 32% |

| Work responsibilities | |

| Primary/patient care | n = 16, 73% |

| OB/GYN care | n = 2, 9% |

| Clinic administration/ management | n = 8, 36% |

| Case management | n = 2, 9% |

| Mental health training | |

| Undergraduate | n = 2, 9% |

| Graduate school/coursework | n = 7, 32% |

| Medical school/residency | n = 9, 41% |

| Continuing medical education | n = 4, 18% |

| Workshops/seminars/training | n = 2, 9% |

| Professional experience with mentally ill patients | n = 1, 5% |

Sums can be greater than 100% because of staff with multiple degrees, titles, work responsibilities, and training.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of clinician experiences with mental health issues.

Barriers and Facilitators of Mental Health Care

The barriers and facilitators of mental health care in general that emerged from the four focus groups are summarized in Table 2 with selected examples described below. Few differences were found in the review of jurisdiction-specific clinician focus groups, other than language barriers in the system that treats many Spanish-speaking patients; thus, clinician themes were not further divided by jurisdiction. In general, the barriers described by informants mirror those found by other researchers who study access to mental health care (Cristofalo et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2008; Meredith et al., 2009). Prominent is the issue of “competing demands” because limited time is often cited by providers when managing mental health problems in primary care and because mental health problems are seen as too complex to manage (Klinkman, 1997). Providers describe barriers such as stigma about seeking care in mental health settings, over-reliance on psychotropic medication intervention rather than on psychotherapy, and patients who “bounce back” to primary care after being referred without resolution of problems. Administrators highlight financing barriers to providing mental health care, and clinicians are not sure how to code for their time if they provide mental health treatment. Clinics often end up narrowing the scope of mental health problems they treat or the number of visits offered.

TABLE 2.

Barriers and Facilitators of Mental Health Care

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional/administrator |

|

|

| Clinical/clinician |

|

|

Administrators (three of six participants) who also performed clinical duties were categorized with the administrator group.

MH indicates mental health.

In contrast, a trusting relationship with the primary care provider is seen as a facilitator, a resource for exploring mental health problems. In addition, the “medical home” model of care supports on-site mental health care provision and therefore better access to care. Other facilitators mentioned included low staff turnover, which is consistent with the two previous points, recognition of how mental health problems affect functioning, and provider comfort with mental health issues.

Trauma-Specific Barriers

Certain themes were identified in the focus groups that had particular relevance to trauma. Because our interest is in developing trauma-specific intervention for primary care patients, we have highlighted these issues.

-

The term trauma is more commonly associated with physical rather than emotional injury. This connotation can make trauma discussions confusing, especially when emotional trauma accompanies physical trauma.

Trauma, I think, has a very unique meaning. I think people in general don’t necessarily associate it with a mental health issue. They think of it as something that’s like being blown up or something like that. -

Trauma is normalized and not considered to be a mental health problem. Patients with trauma histories may not perceive the consequences of the trauma as a reason to seek help.

We all agree on the violence, but does the community though? Again, things that we see as violence or trauma, they may not see it that way and they certainly may not be willing to tell you about it.Many people, these people that have posttraumatic stress disorder don’t view themselves as being mentally ill. People who are blatantly schizophrenic recognize that they have some illness that is truly causing them great problems. People with posttraumatic stress had a bad thing happen to them. And many of us grew up in a socioeconomic climate of - get over it. Get on with it. -

Trauma is commonly encountered in primary care and negatively affects clinical outcomes. Both administrators and clinicians agreed that there is high trauma exposure among their patients. Clinicians observe an association between somatic symptoms and trauma, especially childhood sexual abuse, among high users of health care.

I’m struck frequently by the people that we see who are in the lower socioeconomic strata who don’t seem to be able to get out of it. And then as you get to know them after 1 or 2 years what comes out is the posttraumatic stress thing that the patient is not aware of that has never been addressed, that was something dreadful that happened, that is not at all uncommon. -

Primary care providers express discomfort about discussing trauma with their patients. In contrast with discussing depression, clinicians avoid the topic of trauma because the specifics of patients’ trauma histories can be overwhelming.

One of the things that is a reality for doctors is a lot of the times, they don’t even want to ask certain questions because you’re opening “Pandora’s box.” That you don’t have the resources with which to even go there. …that they’ve had the trauma of having to cross borders,… I don’t even want to ask them frankly, “How did it go? What problems are you confronting?” because I don’t want to know that Pandora’s box.Even those of us that think we’re on top of our patients, we see that in the last year or so, we see increasing numbers of victims of torture. …The first training session we had, …they explained various techniques of torture. Well, for some of our staff, … they were just not prepared. And they may have been seeing victims of torture and they didn’t know what to ask or what to see.

Suggestions for Improvement

Each group was asked to provide examples of specific ways in which trauma-related mental health care could be improved. Among the suggestions were an updated mental health services list and/or a website of available resources; establishing a “feedback loop” with referral sites—follow-up on patient attendance, adherence, treatments, and outcomes; improving education for clinicians on reporting laws and their role in specific crisis situations; providing education on affordable medications, rather than on the use of expensive newer agents; education to address the needs of the different cultural groups seen; and strategies to avoid bias.

DISCUSSION

Administrator interviews, provider surveys, and four focus groups yielded useful information about the barriers and facilitators of mental health interventions for trauma-related problems in safety net primary care programs. Our study provides more detailed qualitative information about clinical context and provider experiences that complements the work of other investigators. Stigma about mental health treatment and inadequate mental health resources are frequent barriers for referring patients to specialty mental health providers in general (Nadeem et al., 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Our study confirms that this holds true for trauma-related mental health problems as well.

In the context of a struggling clinic ecosystem, opening the “Pandora’s box” of trauma-related problems is not likely to happen. Although this topic was only touched on briefly by respondents, it is possible that providers are reluctant to inquire about trauma because of reporting requirements associated with instances of domestic violence or physical or sexual abuse. There were differences in perceived barriers and facilitators at the institutional and clinical levels that likely relate to the different roles assumed by administrators and clinicians. The lack of differences in barriers and facilitators between jurisdictions may have to do with the common and potent effects of poverty and limited resources for all patients served.

Most informants in the study have had direct experience caring for a low-income, uninsured predominantly minority patient population, which informed their discussion of trauma-related problems. However, our survey data reveal that 50% of clinicians have been working in their health care setting for less than 2 years. High staff turnover is often the case among community-based clinics that serve the poor where provider burnout due to inadequate supports is common. Maintaining a trusting patient-provider relationship is difficult when staff turnover and patient instability are combined.

Because mental health problems are seen as a reality of primary care, all jurisdictions expressed the wish for more integrated mental and primary care services, including more on-site mental health services, although they acknowledge the funding and reimbursement obstacles that limit this option. However, integration alone is not enough, and linkages to specialty services, especially those that are trauma specific, will still be needed. The referral process between the mental and primary care systems of care could be improved through better quality and up-to-date information about available mental health services. However, the “feedback loop” between these systems/providers is not well established. Our findings are in line with those of Meredith et al. (2009), in which systems-level barriers negatively impact the ability and will of administrators and clinicians to manage trauma-related mental health problems.

A systems-level facilitator of integrated care is the “medical home” concept that builds on established trust at the community level. Providing better tools for detection and modifying the system of care to more readily incorporate mental health treatment are examples of interventions suggested. Collaborative care approaches for treatment of depression could be expanded or modified to include trauma-specific interventions but will need testing regarding effectiveness. Scaffolding mental health treatment onto ongoing trusting relationships between patients and primary care providers is an important care facilitator.

Relative discomfort addressing trauma issues was evident from the clinician focus groups, consistent with provider self-ratings of the level of comfort and previous research (Green et al., 2011; Meredith et al., 2009). Although providers rated themselves as generally comfortable with mental health and psychosocial issues in surveys, they reported more discomfort in the focus group discussions. Reluctance to discuss trauma issues, in particular, has been found even among mental health providers who treat patients in public mental health clinics (Frueh et al., 2006). However, primary care clinicians have less training and fewer resources to devote to managing trauma-related problems such as PTSD. Additional education and training could help overcome this barrier. Clinicians should consider patient preferences for care, especially in light of findings that low-income and minority groups may prefer counseling interventions for emotional problems to medications (Eisenman et al., 2008; Nadeem et al., 2008).

Limitations

We enrolled a relatively small sample of respondents (total of 32 participants), although we sampled across three different jurisdictions to enhance generalizability. Furthermore, our participants were a convenience sample of willing administrators and clinicians. The study focused on trauma, and, although respondents compared trauma-related problems with common problems such as depression and anxiety seen in primary care, specific psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia and substance abuse were not discussed. We did not specifically ask them to define what constitutes a trauma-related psychiatric disorder. Another limitation of our methods is that we did not specifically examine the extent to which the participants’ views of barriers and facilitators of trauma care overlapped or diverged from patients’ views.

CONCLUSIONS

The qualitative data gathered in this study suggest that trauma-related problems are both similar to and different from other mental disorders encountered in primary care, like depression. The participants seemed to be less comfortable with trauma. This work points to strategies to facilitate appropriate treatment for trauma-related mental health problems encountered in primary care. Modifiable elements, such as making the best use of short clinic visits, improving clinician skills and confidence about addressing trauma and PTSD, improving integration and/or linkages between mental and primary care services (Pomerantz et al., 2008), and advocating for better reimbursement for primary care provision of mental health treatments, are good candidates for trauma-focused intervention development.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (P20 MH 068450) to Bonnie L. Green.

Footnotes

The views expressed are those of the Dr. Chung and do not reflect the official position or views of the US Federal Government, National Institutes of Health, or the National Institute of Mental Health.

The views expressed in this article are those of Dr. Frank and do not necessarily reflect the official position or views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cristofalo M, Boutain D, Schraufnagel TJ, Bumgardner K, Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne PP. Unmet need for mental health and addictions care in urban community health clinics: Frontline provider accounts. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:505–511. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RG, Ressler KJ, Schwartz AC, Stephens KJ, Bradley RG. Treatment barriers for low-income, urban African Americans with undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:218–222. doi: 10.1002/jts.20313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman DP, Meredith LS, Rhodes H, Green BL, Kaltman S, Cassells A, Tobin JN. PTSD in Latino patients: Illness beliefs, treatment preferences, and implications for care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1386–1392. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0677-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley M, Minkoff J, Barken H. Breast cancer screening and trauma history. Women Health. 2001;34:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Schnurr PP. The relationship between trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and physical health. In: Friedman MJ, Charney DS, Deutch AY, editors. Neurobiological and clinical consequences of stress: From normal adaptation to post-traumatic stress disorder. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1995. pp. 507–524. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Grubaugh AL, Sauvageot JA, Wells C. Clinicians’ perspectives on cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1027–1031. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: A systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL. Psychosocial research in traumatic stress: an update. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7:341–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02102782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Kaltman S, Frank L, Glennie M, Subramanian A, Fritts-Wilson M, Neptune D, Chung J. Primary care providers’ experiences with trauma patients: A qualitative study. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Kimerling R. Trauma, PTSD, and health status. In: Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Krause ED, Revicki D, Frank L, Miranda J. Impact of PTSD comorbidity on one-year outcomes in a depression trial. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:815–835. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkman MS. Competing demands in psychosocial care. A model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, Ryden J, Derogatis LR, Bass EB. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: Unhealed wounds. JAMA. 1997;277:1362–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrano MA, Brzyski RG, Bernstein DP, Ross JS, Hyatt-Santos JM. Childhood abuse and neglect histories in low-income women: Prevalence in a menopausal population. Menopause. 2004;11:208–213. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000087984.28957.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Green BL, Basurto-Davila R, Cassells A, Tobin J. System factors affect the recognition and management of posttraumatic stress disorder by primary care clinicians. Med Care. 2009;47:686–694. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190db5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, Belin T. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Belin T, Revicki D. One-year outcomes of a randomized clinical trial treating depression in low-income minority women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:99–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz A, Cole BH, Watts BV, Weeks WB. Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: Combining integrated care and advanced access. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold AA, Acierno R, Resnick HS. Trauma, PTSD, and health risk behaviors. In: Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Robins CS, Ware NC, dos Reis S, Willging CE, Chung JY, Lewis-Fernandez R. Dialogues on mixed-methods and mental health services research: Anticipating challenges, building solutions. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:727–731. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.7.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robohm JS, Buttenheim M. The gynecological care experience of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a preliminary investigation. Women Health. 1996;24:59–75. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth SH, Newman E, Pelcovitz D, Van der Kolk BA, Mandel FS. Complex PTSD in victims exposed to sexual and physical abuse: Results from the DSM-IV field trial for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10:539–555. doi: 10.1023/a:1024837617768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Green BL. Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Clark MK, McCarthy AM, Ronis DL. PTSD and physical comorbidity among women receiving Medicaid: Results from service-use data. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:45–56. doi: 10.1002/jts.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AC, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D, Russo J. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. Am J Med. 1999;107:332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Katon W, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Newman E, Wagner AW. Health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:369–374. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T, Clum G. Psychological distress associated with interpersonal violence: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:115–140. [Google Scholar]