Abstract

It is well known that ligand binding to the high-affinity GM-CSF receptor (GMR) activates JAK2. However, how and where this event occurs in a cellular environment remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that clathrin- but not lipid raft-mediated endocytosis is crucial for GMR signaling. Knockdown expression of clathrin heavy chain or intersectin 2 (ITSN2) attenuated GMR-mediated activation of JAK2, whereas inhibiting clathrin-coated pits or plagues to bud off the membrane by the dominant-negative mutant of dynamin enhanced such event. Moreover, unlike the wild-type receptor, an ITSN2-non-binding mutant of GMR defective in targeting to clathrin-coated pits or plagues [collectively referred to as clathrin-coated structures (CCSs) here] failed to activate JAK2 at such locations. Additional experiments demonstrate that ligand treatment not only enhanced JAK2/GMR association at CCSs, but also induced a conformational change of JAK2 which is required for JAK2 to be activated by CCS-localized CK2. Interestingly, ligand-independent activation of the oncogenic mutant of JAK2 (JAK2V617F) also requires the targeting of this mutant to CCSs. But JAK2V617F seems to be constitutively in an open conformation for CK2 activation. Together, this study reveals a novel functional role of CCSs in GMR signaling and the oncogenesis of JAK2V617F.

Keywords: GM-CSF receptor, Jak2, casein kinase 2, clathrin-coated pit, myeloproliferative disorders

Introduction

The granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor (hereafter referred to as GMR) is composed of a ligand-specific α subunit (hereafter referred to as GMRα) and a β subunit (hereafter referred to as GMRβ) that is shared with the interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-5 receptors.1-3 GM-CSF binds to GMRα with low affinity but to the GMRα/GMRβ complex with high affinity and triggers receptor activation.3 Moreover, GMR does not harbor any intrinsic kinase activity but associates with the tyrosine kinase JAK2, which is required for the transphosphorylation of GMRβ and the initiation of receptor signaling. Although the cytoplasmic domains of both GMRα and GMRβ are essential for receptor activation,4,5 the receptor-JAK2 association appears to be mainly mediated through GMRβ.6-8 A recent structural study suggests that the GMR ternary complex (one ligand plus one α and one β subunit) assembles into a dodecamer, or higher-order complex, which brings two GMRβ dimers into close proximity and provides for the functional dimerization and activation of GMR.9

The JAK2 protein has a protein tyrosine kinase domain and a pseudokinase domain, which via an intra-molecular interaction with the kinase domain, plays a negative role in regulating the JAK2 kinase activity.10,11 One essential event for JAK2 to be fully activated involves tyrosine phosphorylation within its activation loop (Y1007-Y1008), which likely would cause a conformational change and remove steric constraints imposed by the nonphosphorylated form.12 A Val-to-Phe point mutation at position 617 of JAK2 (JAK2V617F) was identified in the majority patients with neoplastic myeloproliferative disorders.13,14 Distinct hallmarks of tumor cells with the V617F mutation include cytokine-independent growth and hyper-responsiveness to many cytokines including Epo, GM-CSF, IL-3, SCF and IGF1.15-20 Notably, the V617F mutation is located within the pseudokinase domain of JAK2, suggesting that such mutation may interfere with the ability of the pseudokinase domain to negatively regulate JAK2 kinase activity.10 On the other hand, co-expression of homodimeric or one subunit of the heterodimeric cytokine receptors that contain the JAK-binding motif greatly promotes JAK2V617F-mediated autonomous cell growth.21-23 However, how cytokine receptor facilitates JAK2V617F activation in a ligand-independent manner remains unclear.

Intersectins (ITSNs) are evolutionarily conserved adaptor/scaffold proteins that have been shown to associate with numerous proteins implicated in cell signaling, cytoskeletal organization and endocytosis.24 A recent study further suggested that ITSNs play a role in nascent clathrin-coated pit (CCP) assembly.25 On the other hand, caseine kinase (CK2) is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase with a broad subcellular localization.26,27 CK2 is also enriched in clathrin-coated vesicles (CCV) and can phosphorylate many accessory proteins involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) pathway, including AP2, amphiphysin and clathrin light chain (CLC).28 Recently, Zheng et al. demonstrated that JAK2 activation by oncostatin M, IFNγ and growth hormone and auto-activation of JAK2V617F are both CK2-dependent.29 However, the fundamental difference of these two events is not clear.

It has been well documented that ligand-binding to the high-affinity GMR complex activates JAK2.6-8 However, how and where this event occurs in a cellular environment remains unclear. This study aims to explore this important issue.

Results

Surface GMRβ molecules form ligand-independent nano-scale clusters, some of which are colocalized with CCPs

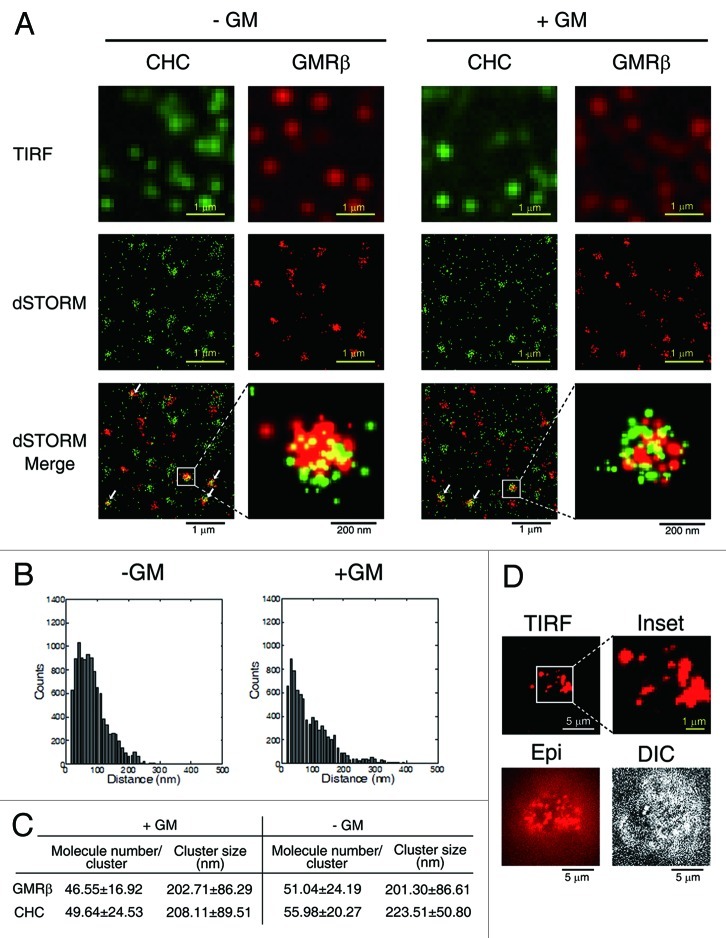

As an initial attempt to study how GMR activates JAK2, we employed the direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) using a total internal reflection configuration30,31 to visualize the GMR complex transiently expressed in HeLa cells (see Materials and Methods). This such system, which can determine the position of a single molecule with an accuracy of 20 nm in the X-Y axis, revealed that GMRβ in the context of either liganded (+GM-CSF) or un-liganded (-GM-CSF) GMR complexes all appeared as a cluster with a diameter of approximately 200 nm. Each cluster was estimated to contain approximately 40–50 GMRβ molecules (Fig. 1A‒C). Very similar results were obtained when GMRβ-paGFP (a GMRβ molecule C-terminally tagged with a photo-activatable GFP that can transduce GM-CSF signal) expressed in HeLa cells were analyzed by photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) (Fig. S1). Moreover, a similar nano-scale cluster of GMRβ was also observed in a human erythroleukemia cell line TF-1 expressing endogenous GMR (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, in terms of size and the number of molecules per cluster, such a distinct GMRβ-containing punta structure is very similar to that of CCPs visualized by staining with anti-clathrin heavy chain (CHC) antibody (Fig. 1A and C). Of note, the size of CCPs measured by the dSTORM system described here is consistent with that measured by the three-dimensional stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy.32 Further analysis revealed that some surface GMRβ clusters were co-localized with CHC (Fig. 1A, clusters indicated by arrows), suggesting that there is a functional interaction between GMRβ and the CME machinery.

Figure 1. Surface GMRβ molecules form ligand-independent nano-scale clusters, some of which are colocalized with CCPs. (A) TIRF and dSTORM images of HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP (not shown) and GMRβ (red, labeled by antibody, see Materials and Methods) in medium containing or not containing GM-CSF (± GM). Endogenous CHC was stained by specific antibody (green). (B) The size of a GMRβ cluster shown in (A) was calculated by the pair distance analysis (see Materials and Methods). Shown here are two representative histograms of distances of GMRβ pairs within a GMRβ cluster. (C) Estimated cluster size and number of GMRβ or CHC molecules in each cluster shown in (A). Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 100. (D) Images of endogenous surface GMRβ in TF1 cells taken by TIRF, Epifluorescence (Epi), or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

The CME machinery is important for GMR signaling

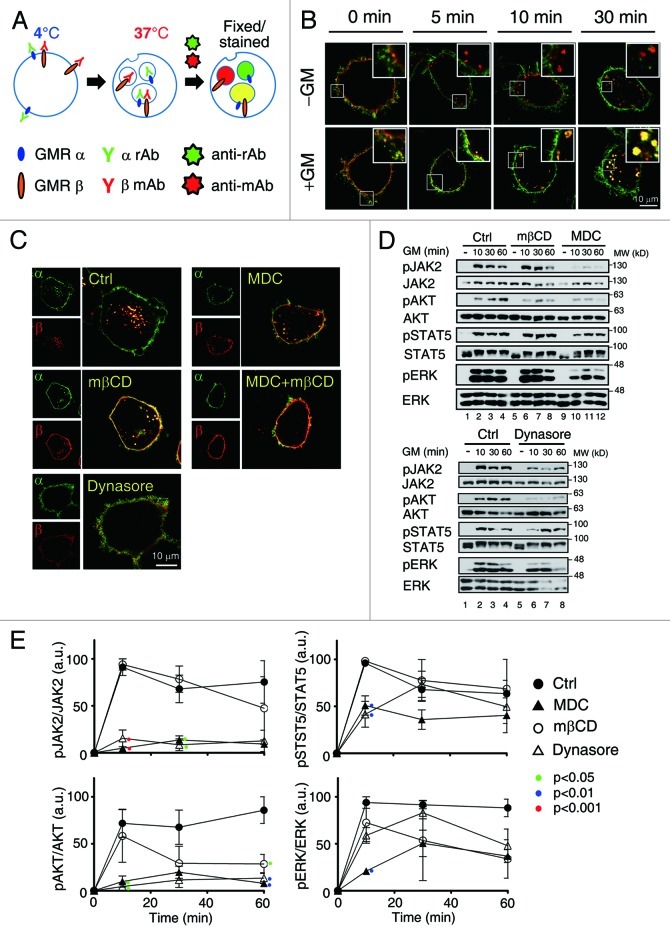

Co-localization of GMRβ with CCPs prompted us to investigate how surface GMRα and GMRβ are internalized in response to GM-CSF stimulation and what role endocytosis may play in GMR activation. To address this issue, we first performed the internalization assay using HeLa cells transiently co-expressing human (h) GMRα and GMRβ and antibodies specifically recognizing these two receptor subunits (see Materials and Methods). We noticed that GMRβ was constantly internalized from cell surface irrespective of the presence or absence of ligands, whereas GMRα could only be co-internalized with GMRβ under ligand-stimulated conditions (Fig. 2A and B). Similar results were obtained when the internalization assay was performed with fluorochrome-labeled Fab fragments of both GMRα and GMRβ antibodies (Fig.S2). Next, we examined whether pretreatment of cells with inhibitors of either clathrin- or lipid raft-mediated endocytic pathway (MDC and MβCD, respectively, see Fig. S3A) would block ligand-stimulated GMR complex endocytotsis. Figure 2C shows that the internalization of the GMR complex was partially suppressed with either inhibitor alone and was nearly completely blocked when cells were treated simultaneously with both MDC and MβCD. Moreover, dynasore, which inhibits both clathrin- and lipid raft/caveolae-mediated endocytosis (Fig. S3A), behaved like the combination of MDC and mβCD in the endocytosis assay shown in Figure 2C. Of note, similar inhibition results were observed for the internalization of un-liganded GMRβ (Fig. S3B), indicating that ligand-independent internalization of GMRβ is also mediated by both clathrin- and lipid raft-dependent pathways.

Figure 2. Inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis attenuates GMR signaling. (A) A schematic diagram for the GMR internalization assay. α rAb and β mAb stand for the rabbit and mouse antibodies recognizing GMRα and GMRβ, respectively; Anti-rAb and anti-mAb stand for Alexa flour® 488- and Alexa flour® 555-conjugated secondary antibodies recognizing α rAb and β mAb, respectively. (B) HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα (green) and GMRβ (red) were shifted to 37°C in medium containing or not containing GM-CSF (± GM) for 0–30 min and processed as outlined in (A), followed by image analysis using confocal microscope. (C) Liganded receptor endocytosis was allowed to proceed in HeLa cells transiently expressing GMRα and GMRβ in the presence of the indicated inhibitors. (D) Activation of JAK2, AKT, STAT5 and ERK in αβ-Ba/F3 cells pre-treated with MDC (300 μM) mβCD (5mM) or dynasore (80 μM) for 30 min prior to re-stimulation with hGM-CSF for the indicated time was analyzed by immunoblotting. Shown here is one representative result. (E) shows the average activation extent (phosphorylation) of each indicated protein (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments. Only the p values of those treatment groups that are statistically significantly different from the control group at the same time point are as indicated (one way ANOVA, Tukey’s post test).

We next investigated which endocytosis pathway might be more important for transducing receptor-activated signals. To this end, a Ba/F3 stable clone expressing human GMRα and GMRβ (αβ-Ba/F3 cells, see also Fig. 3B) were pre-treated with MDC, mβCD or dynasore prior to GM-CSF stimulation, and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting analysis. As shown in Figure 2D and E, mβCD in general did not significantly affect GM-CSF-induced activation of JAK2, AKT, STAT5 or ERK [revealed by immunoblotting using anti-pJAK2 (Y1007/1008), anti-pAKT(S473), anti-pSTAT5(Y694) and anti-pERK (T202/Y204) antibody, respectively], except at a later time it did markedly inhibit AKT activation. In contrast, at most time points examined, MDC and dynasore each strongly suppressed ligand-induced activation of JAK2 and AKT, while exerting no or less inhibitory effect on the activation of STAT5 and ERK. Together, these results strongly suggest that interaction between the GMR complex and the CME machinery is important for GMR signaling.

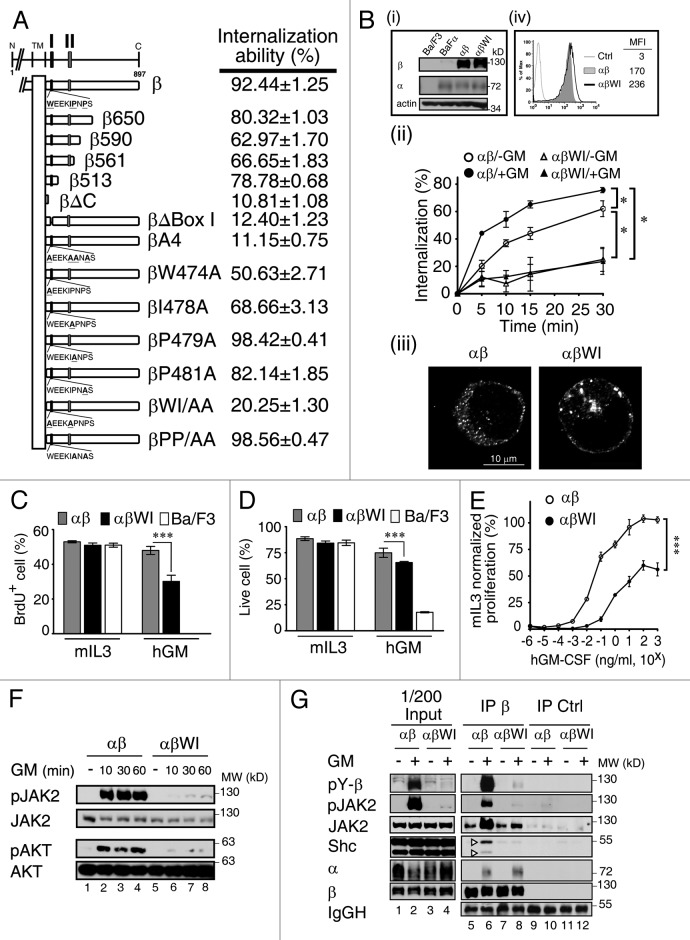

Figure 3. The WxxxI motif within the Box I region of GMRβ is critical for receptor endocytosis and GM-CSF signaling. (A) Schematic representation of wt and various mutants of GMRβ used in this study. The internalization ability of these molecules was determined using the HeLa cell system at the 30 min time point in medium containing GM-CSF. The results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 50). Box I (I; a.a. 474–482) and Box II (II; a.a. 534–544) regions are as indicated. (B) (i) Immunoblotting analysis of the total protein expression levels of GMRα, wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ in parental Ba/F3 cells, Ba/F3 cells stably overexpressing GMRα (BaFα), αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells. (ii) The internalization kinetics of wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ in αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells was analyzed in medium containing or not containing GM-CSF. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); *p < 0.05. (iii) Confocal analysis of the subcellular distribution of wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ in fixed αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells. (iv) Cell surface expression levels of wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ in αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (MFI, mean fluorescence intensity). (C and D) The proliferation and viability responses of parental Ba/F3, αβ- and αβWI-Ba/F3 cells cultured in medium containing 2 ng/ml of murine IL-3 (mIL-3) or human GM-CSF (hGM) for 24 h were determined by the BrdU incorporation assay (C) and Annexin V/PI staining (D), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); ***p < 0.001. (E) The proliferation response of αβ- and αβWI-Ba/F3 cells cultured in medium containing various concentrations of hGM-CSF was determined using the cell proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche). Data presented (mean ± SEM, n = 6; ***p < 0.001) are normalized to mIL-3-mediated proliferation. (F) Lysates from αβ- and αβWI- Ba/F3 cells that were left untreated (-) or stimulated with hGM-CSF for various time points were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific to each indicated molecule. (G) Cytokine-deprived αβ- and αβWI-Ba/F3 cells were re-stimulated with GM-CSF for 10 min and their cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with control or GMRβ-specific antibody. The immune complexes along with the input lysates (1/200) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibody as indicated. pY, phospho-tyrosine.

The WxxxI motif of GMRβ is critical for GMR endocytosis and signaling

We next examined how receptor endocytosis might affect GMR signaling. To address this issue, we first mapped the domain of GMRβ that was important for this process. Our initial mapping studies using HeLa cells transiently expressing various receptor mutants indicated that the Box I domain (residues 474 to 482) was critical for the internalization process, as deletion of this domain markedly attenuated the internalization ability of the receptor (12.4%; Fig. 3A; Fig. S4A). Of note, the Box I motif of GMRβ is highly conserved among many mammalian species with a consensus sequence of WxEKIPNPS. We were particularly interested in the role of the four hydrophobic amino acid residues within this region, namely W474, I478, P479 and P481. Further mutagenesis analysis showed that whereas double mutation of both P479 and P481 residues to alanine (βPP/AA) did not exert any significant effect, double mutation of both W474 and I478 residues to alanine (βWI/AA) resulted in a profound loss of the internalization ability of the liganded GMRβ subunit (~20%). The impact of the WI to AA mutation on GMR endocytosis was further investigated in a murine IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 pro-B cell line system. For this experiment, two Ba/F3 derivatives stably co-expressing human GMRα with either wt- (αβ-Ba/F3) or the WI/AA mutant of human GMRβ (αβWI-Ba/F3) to comparable levels were analyzed (Fig. 3B, panel i). As shown in panel ii of Figure 3B, wt-GMRβ internalized rapidly from cell surface, and approximately 60% were endocytosed within 30 min in the absence of GM-CSF, but were further enhanced to approximately 75% in the presence of this ligand. Under the same conditions, endocytosis of the WI/AA mutant in αβWI-Ba/F3 cells was drastically reduced, with only ~20% irrespective of the presence or absence of ligand. Consistent with this result, confocal and flow cytometric analyses both revealed that, during steady-state, a relatively larger fraction of the WI/AA mutant was localized to the plasma membrane compared with wt GMRβ (Fig. 3B, panels iii and iv).

We next examined whether the WI/AA mutation would affect the growth of αβWI-Ba/F3 cells in response to GM-CSF stimulation. When cultured in medium containing murine IL-3 (mIL-3), both αβ- and αβWI-Ba/F3 cells proliferated (measured by DNA synthesis, Fig. 3C) and survived (Fig. 3D) like parental Ba/F3 cells. However, when they were shifted to hGM-CSF-containing medium, these two cell lines behaved differently. Whereas αβ-Ba/F3cells grew well, like they were in mIL-3 containing medium, αβWI-Ba/F3 cells manifested a significant reduction both in DNA synthesis and cell survival compared with αβ-Ba/F3 cells (30% vs 48%, Fig. 3C; 65% vs 75%, Fig. 3D). Further analysis of their proliferation response in various doses of hGM-CSF (normalized to mIL-3-mediated proliferation) revealed that αβWI-Ba/F3 cells proliferated in hGM-CSF with an ED50 of 1 ng/ml, compared with 0.02 ng/ml observed for αβ-Ba/F3 cells. The maximum proliferation response of αβWI-Ba/F3 cells in hGM-CSF could only reach to ~60% of that of αβ-Ba/F3 cells (Fig. 3E). Next, we examined whether the WI/AA mutation would impair GMR-mediated signaling. The results showed that, compared with control αβ-Ba/F3 cells, following GM-CSF stimulation, a profound suppression of JAK2 and Akt phosphorylation (~80–90%) and a marginal to moderate reduction in the phosphorylation of both ERK and STAT5 were observed in αβWI- Ba/F3 cells (Fig. 3F, lanes 2–4 vs 6–8; Fig. S4B). Similar effects were also observed in HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα with wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ (Fig. S4C). Moreover, we observed that, although ligand stimulation induced similar amounts of GMRα binding to wt or mutant GMRβ, ligand-induced association of JAK2 and a scaffold protein Shc with GMRβ was only markedly enhanced in αβ- but not in αβWI-Ba/F3 cells (Fig. 3G, lane 6 vs lane 8), which correlated well with the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of both GMRβ and JAK2 in these two cell lines (compare lanes 6 and 8). Taken together, these results reveal that the WxxxI motif of GMRβ plays a critical role in GMR endocytosis and signaling.

Targeting of the GMR complex to the clathrin-coated structures at the plasma membrane via interaction with intersectin 2 is critical for receptor signaling

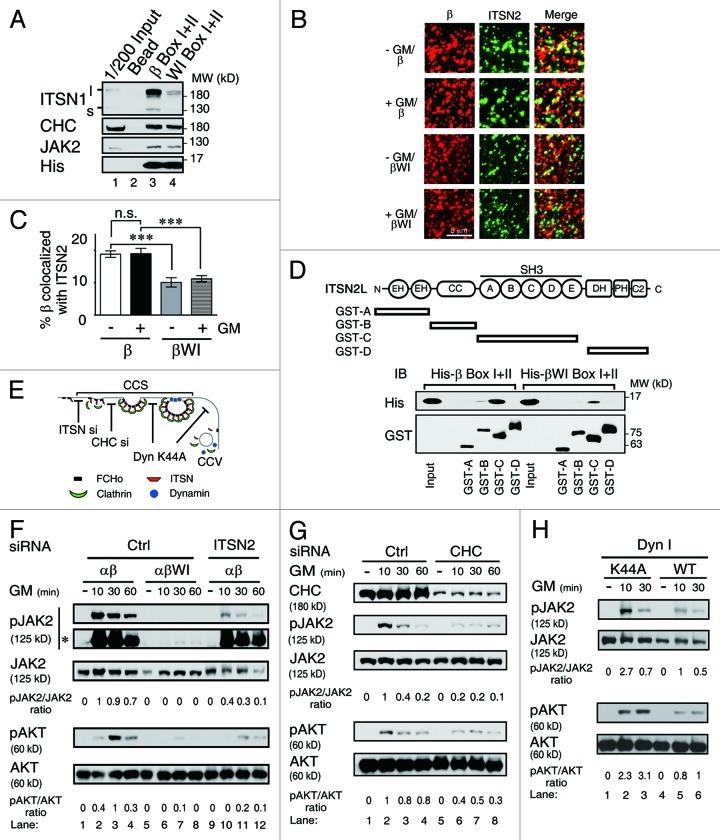

We next examined how the WI/AA mutation might impair the interaction between GMRβ and the CME machinery. To address this issue, we first compared components in the clathrin-containing complex that may differentially interact with wt- and the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ by a pull-down assay using mouse brain lysates that were enriched for the endocytic complex components.25 Immunoblotting analysis of pull-down lysates indicated that the Box I+II domain of the WI/AA mutant manifested a markedly reduced ability to pull-down intersectin1 (ITSN1, the predominant isoform of intersectins in brain), while retaining a similar ability as that of the wt protein to pull-down CHC (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 4). Of note, similar amounts of JAK2 could be pulled down by these two types of recombinant molecules.

Figure 4. GMRβ interaction with ITSN is required for ligand-dependent activation of JAK2 at CCSs. (A) His-tagged recombinant proteins containing the Box I and II region from wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ were incubated with mouse brain lysates. The interacting proteins pulled-down by the nickel beads along with 1/200 of the input lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using antibody specific to ITSN1, CHC, JAK2 or His-tag as indicated. (B) HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP (not shown), ITSN2-EGFP (green) and wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ were stained with mouse anti-GMRβ antibody and then with Alexa Flour® 633-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (red) before analyzed by TIRF microscopy. The percentage of co-localization of wt or mutant GMRβ (red) with ITSN2 (green) at cell surface shown in (B) was analyzed by MetaMorph software and presented as mean ± SEM (n = 10, ***p < 0.001) (C). (D) Recombinant GST-fusion proteins containing various subdomains of ITSN2 as indicated were used to pull-down His-tagged recombinant proteins containing the Box I and II regions of wt or the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ. Recombinant proteins pulled-down by the glutathione beads along with the input were analyzed by immunoblot using antibody specific to the His-tag or the GST-moiety. (E) A simplified scheme showing where ITSN2 siRNA, CHC siRNA, and the K44A mutant of dynamin may interfere with the clathrin-mediated endocytosis pathway. (F) Cell lysates from αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells treated with control siRNA (lanes 1–8) or ITSN2-specific siRNA (lanes 9–12), followed by GM-CSF deprivation and re-stimulation for 0–60 min were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibody specific to each indicated molecule. *, pJAK2 signals on a longer exposed film. (G) Same as in (F) except that αβ-Ba/F3 cells treated with control (lanes 1–4) or CHC-specific siRNA (lanes 5–8) were analyzed. (H) αβ-Ba/F3 cells transiently expressing wt or the K44A mutant of dynamin I were sorted out by flow cytometry and deprived of cytokine for 2 h prior to being stimulated with GM-CSF for 10 or 30 min. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies recognizing the indicated molecule.

Next, we performed the immuno-colocalization experiment to examine whether intersectin 2 (ITSN2), the predominant isoform of intersectins present in the hematopoietic cell system used in this study, would also manifest a similar property as ITSN1 mentioned above. To address this issue, HeLa cells were transiently co-transfected with vectors expressing GFP-ITSN2, GMRα-CFP and GMRβ. Those GMRβ molecules (wt or mutant) residing on the cell surface and co-localized with GFP-ITSN2 were visualized by TIRF microscopy and quantified by the MetaMorph software. As shown in Figure 4B and C, a significantly reduced fraction of the WI/AA mutant was found to be co-localized with ITSN2 on cell surface compared with the wt protein (~2-fold less). Further pull-down analysis using bacterially produced recombinant proteins indicated that GMRβ directly interacted with ITSN2, and such interaction was mainly mediated through a domain in GMRβ that contains the WxxxI motif and the SH3 domain of ITSN2 (Fig. 4D).

Intersectins are essential scaffold proteins in clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Fig. 4E). Reduced association between GMRβ and intersectins may result in reduced recruitment of the GMR complex to CCPs or the so-called clathrin-coated plaques,33 which subsequently results in reduced endocytosis. Since CCPs or clathrin-coated plaques can’t be distinguished in our experimental systems (see below), unless otherwise indicated, a more generalized term “clathrin-coated structures (CCSs)” will be used hereafter to refer to either one or both of these two structures. We next examined whether recruitment of the GMR complex to CCSs or CCVs was critical for receptor signaling, which was compromised in αβWI-Ba/F3 cells. To address this issue, we first tested whether knocking down the expression of ITSN2 or CHC in αβ-Ba/F3 cells would affect GMRβ internalization and GM-CSF signaling. Consistent with the WI/AA mutant phenotype, knockdown of ITSN2 (Fig. S5A) or CHC expression (Fig. 4G, lanes 5 to 8) resulted in a significant reduction of GMRβ endocytosis (Fig. S5B and C) and phosphorylation of JAK2 and Akt, compared with control cells (Fig. 4F and G). We next examined the effect of the dominant-negative mutant of dynamin (K44A), which was shown to block CCV formation but leave the structure and function of CCSs intact.34 The dominant-negative dynamin (K44A) indeed blocked GMRβ endocytosis (Fig. S5D and E). However, intriguingly, it did not interfere with receptor signaling. In fact, to the contrary, it enhanced the latter event as revealed by increased phosphorylation of both JAK2 and Akt upon GM-CSF stimulation, compared with cells expressing wt dynamin (Fig. 4H).

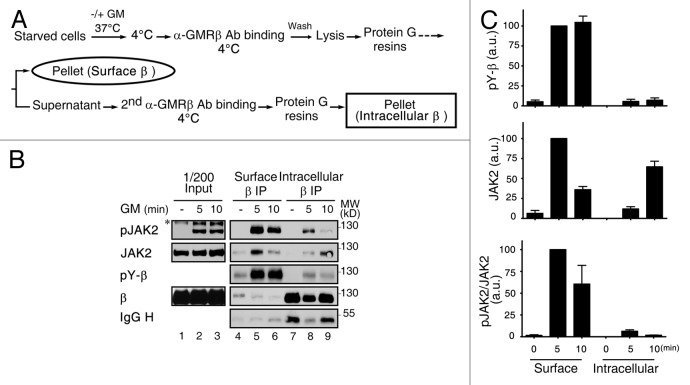

To further confirm that the majority, if not all, of receptor-activated signaling events initiate when the liganded receptor still resides on the plasma membrane, we performed the sequential immunoprecipitation experiment as outlined in Figure 5A. In this experiment, the GMRβ complexes residing on cell surface or being internalized into the intracellular location were separated by two sequential immunoprecipitation steps using GMRβ-specific antibody. These two groups of immune complexes were then analyzed by immunoblotting to compare the binding affinity (i.e., extent of protein association) and the degree of activation (i.e., tyrosine phosphorylation levels) of JAK2 that was associated with the receptor. As shown in Figure 5B, GM-CSF induced a marked increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of GMRβ, and the majority of such events occurred at the cell surface instead of at an intracellular location (compare lanes 5–6 to 8–9; see Fig. 5C for quantification). A similar trend was also observed for JAK2; i.e., in response to cytokine stimulation, majority of the JAK2/GMRβ association and JAK2 activation (tyrosine-phosphorylation) was found to take place at cell surface (Fig. 5B and C). Taken together, these results together with those shown in Figure 4 suggest that liganded GMR complex begins to activate its downstream signaling event when it is localized to CCSs at plasma membrane before it is fully internalized.

Figure 5. Activation of GMRβ/JAK2 initiates at the plasma membrane. (A) A schematic diagram showing sequential immunoprecipitation of GMRβ residing on cell surface or an intracellular location. (B) HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα and GMRβ were left untreated (-) or stimulated with GM-CSF for 5 or 10 min and then underwent sequential immunoprecipitation of GMRβ as outlined in (A). Immune complexes along with 1/200 input lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies as indicated. (C) The extent of tyrosine-phosphorylation of GMRβ (pY-β) or of JAK2 that was associated with GMRβ (JAK2) or activated (pJAK2/JAK2) shown in panel B (lanes 4–9) plus very similar results from two other independent experiments was quantified and plotted as that described in the Materials and Methods.

Targeting of GMR to CCSs is also essential for the autonomous activation of oncogenic JAK2V617F

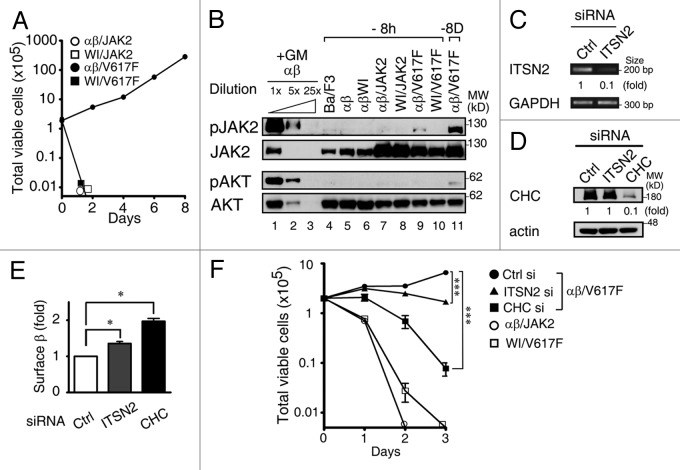

Autonomous activation of JAK2V617F requires the co-expression of either homodimeric or heterodimeric cytokine receptors, including GMRβ.21,22,35 Given that localization of the GMR complex to CCSs is an essential step for GM-CSF-induced activation of JAK2, we examined the possibility that the WI/AA mutation of GMRβ may affect the ability of the receptor to support the auto-activation feature of JAK2V617F. To address this issue, αβ- and αβWI-Ba/F3 cells stably overexpressing wt or the V617F mutant of JAK2 were established and designated as αβ/JAK2, WI/JAK2, αβ/V617F and WI/V617F cells, respectively. As shown in Figure 6A, upon removal of GM-CSF, only αβ/V617F cells were able to proliferate with a doubling time of approximately 24 h, while WI/V617F and two other control stable lines (αβ/JAK2 and WI/JAK2) lost viability quickly and failed to proliferate. Consistent with the proliferation results, immunoblot analysis revealed that, upon deprivation of GM-CSF, only αβ/V617F cells but not WI/V617F or other control cell lines examined in Figure 6B manifested a detectable activation of JAK2 (lane 9 vs lanes 4–8 and 10). Of note, although activation of AKT was hardly detectable in αβ/V617F cells that had been deprived of GM-CSF for 8 h (lane 9), activation of this protein could be clearly observed in a separate experiment, where αβ/V617F cells had been cultured in cytokine-free medium for 8 d (Fig. 6B, lane 11). Given that the WI/AA mutation impaired GMRβ to be recruited to CCSs (Fig. 4) and that JAK2V617F was not activated in cytokine-deprived WI/V617F cells, we reasoned that cytokine-independent activation of JAK2V617F would be dependent on its co-recruitment with the GMR complex to CCSs. To test this possibility, the expression of ITSN2 or clathrin was knocked down in αβ/V617F cells by specific siRNA (Fig. 6C and D), and the growth of these cells along with two other reference cells (αβ/JAK2 and WI/V617F) in cytokine-free medium was analyzed. As shown in Figure 6E, both siRNA treatments increased the numbers of GMRβ to be retained on the cell surface. Importantly, proliferation of αβ/V617F cells was significantly suppressed after 3 d treatment with either ITSN2 or CHC siRNA (Fig. 6F, day 3), consistent with the notion that co-recruitment of JAK2V617F with the GMR complex to CCSs plays a role in the autonomous activation of JAK2V617F in cytokine-free medium.

Figure 6. Autoactivation of JAK2V617F is dependent on the recruitment of GMRβ to CCSs. (A) Growth curves of αβ/JAK2, WI/JAK2, αβ/V617F and WI/V617F cells in medium containing no survival cytokines. Cells to be analyzed were initially cultured in medium containing mIL-3 and then shifted to cytokine-free medium. At various times after cytokine removal, the viability of these cells was determined by trypan-blue staining. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of cell lysates prepared from each indicated cell line after removal of cytokines for 8 h (lanes 4–10) or 8 d (lane 11). Cell lysates from αβ- Ba/F3 cells stimulated with GM-CSF for 10 min (lanes 1–3) were included as positive controls for the immunoblotting analysis. (C-E) The ITSN2 mRNA, CHC protein levels or cell surface levels of GMRβ in control, ITSN2 and CHC knockdown αβ/V617F cells were determined by RT-PCR (C), immunoblotting (D) or flow cytometry (E), respectively. (F) Control, ITSN2- or CHC-knockdown αβ/V617F cells along with two other reference cells (αβ/JAK2 and WI/V617F) were seeded in cytokine-free medium. At 0–3 d after seeding, total viable cell number of these cells was determined by trypan blue staining. Data shown in (A, E and F) are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05.

CCSs serve as platforms for CK2 to activate GMR-associated wt or oncogenic JAK2

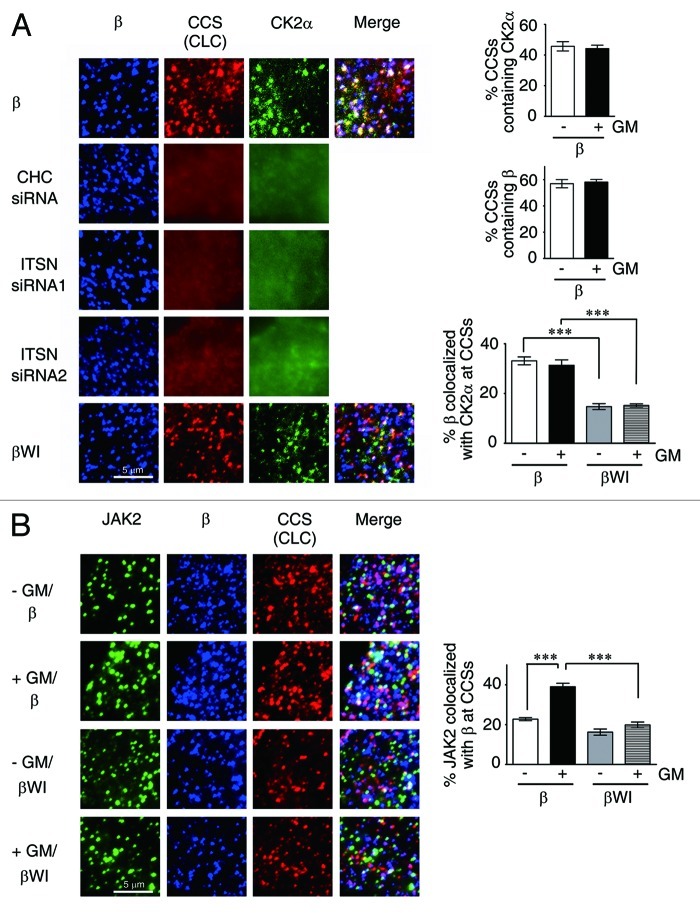

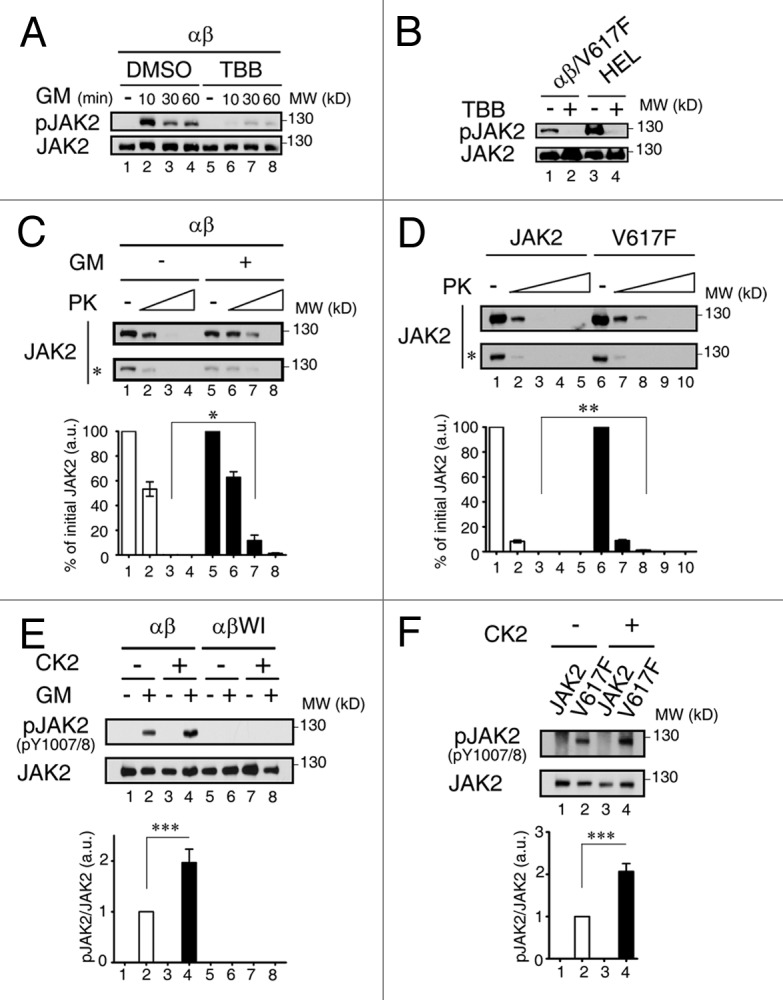

CK2 (Casein kinase 2) is one major protein kinase located in clathrin-coated vesicles36 and has been recently shown to play an important role in oncostatin M-induced activation of JAK2.29 We next examined the possibility that CK2 is also localized to CCSs’ where it can activate GMR complex-bound JAK2. To examine this possibility, we first analyzed HeLa cells co-expressing GMRα-CFP and GMRβ (wt or mutant) together with CK2α-GFP and CLC-RFP (marked for CCSs) by TIRF microscopy. The results shown in Figure 7A revealed that, with or without ligand stimulation, ~45% CCSs contained CK2α-GFP. Ligand treatment also did not significantly alter the fraction of CCSs containing GMRβ (both ~58%). Further analysis showed that, irrespective of the presence or absence of ligand, ~32% of wt GMRβ was colocalized with CK2α-GFP at CCSs, whereas only ~15% of the WI/AA mutant was colocalized with CK2α-GFP at this location. Notably, the distinct puncta structure of CK2α-GFP, but not GMRβ, was disrupted in cells treated with siRNA specific to essential components of CCSs, such as ITSN2 or CHC. Next, we examined whether JAK2 could also be co-recruited with GMRβ to CCSs, since JAK2 was pre-associated with unliganded GMRβ, and such association was greatly enhanced upon ligand stimulation (Fig. 3G). TIRF microscopy analysis revealed that ~23% of JAK2 was co-localized with GMRβ at CCSs, and such association was increased to ~39% upon ligand stimulation (Fig. 7B). In contrast, irrespective of the presence or absence of ligand, only ~18% of JAK2 was co-localized with the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ at CCSs (Fig. 7B). Further analysis showed that colocalization of JAK2 with GMRβ (wt or mutant) and CK2α-GFP at plasma membrane (Fig. 8A) followed a similar pattern as that observed for JAK2/GMRβ association at CCSs (Fig. 7B), and that only JAK2 co-localized with wt but not the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ at CCSs was significantly activated (phosphorylated) upon ligand stimulation (Fig. 8B). We next examined whether GM-CSF-induced activation of JAK2 is dependent on the CK2 activity. The results shown in Figure 9A indicate that this is indeed the case, since pre-treatment of αβ-Ba/F3 cells with the CK2 inhibitor, TBB, significantly attenuated GM-CSF-induced phosphorylation of JAK2 at tyrosine residues 1007 and 1008. Of note, ligand-independent activation of JAK2V617F in αβ/V617F cells or in a JAK2V617F-expressing human erythroid leukemia cell line, HEL, was also inhibited by treatment of cells with TBB (Fig. 9B). Together, these results indicate that ligand-dependent activation of wt JAK2 and ligand-independent activation of JAK2V617F both require CCS-localized CK2.

Figure 7. The WI/AA mutation reduces the colocalization of GMRβ/CK2 or of JAK2/GMRβ at CCSs. (A) TIRF images of HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP (not shown), CK2α-GFP (green), CLC-RFP (red) and wt (β, top panel) or the WI/AA mutant (βWI, bottom panel) of GMRβ (blue) in ligand free-medium. Those images in ligand-containing medium were very similar (not shown). The middle three panels are identical to the top panel, except that the transfection was done in CHC- or ITSN2-knockdown cells. The percentage of CCSs containing CK2α or GMRβ and the percentage of surface GMRβ colocalized with CK2α at CCSs (white color in the “merge” panel) are as illustrated. (B) TIRF images of HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP (not shown), CLC-RFP (red) and GMRβ or βWI (blue) either in medium with or without GM-CSF. Endogenous JAK2 was stained and shown in green. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 10). ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 8. Only JAK2 associated with wt but not the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ at CCSs are activated upon ligand stimulation. (A) TIRF images of HeLa cells co-expressing GMRα-CFP (not shown), CK2α-GFP (green) and GMRβ or βWI (blue). Endogenous JAK2 was stained and shown in red. (B) Same as that shown in Figure 7B, except that activated JAK2 (pJAK2) was stained by anti-pJAK2 (Y1008). Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 10). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 9. Ligand-induced conformational change is required for wt but not oncogenic JAK2 to be activated by CK2. (A) Cell lysates from αβ-Ba/F3 cells treated with DMSO (lanes 1–4) or 60μM of TBB (lanes 5–8) prior to GM-CSF deprivation and re-stimulation (0–60 min) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific to active-form or total JAK2 proteins. (B) αβ/V617F and HEL cells treated with DMSO (lanes 1and 3) or 60μM of TBB (lanes 2 and 4) were deprived of cytokine for 6 h, and cell lysates were analyzed as described in (A). (C) Wt-JAK2 prepared from αβ-Ba/F3 cells with or without ligand stimulation were treated with increasing doses of proteinase K and then analyzed by immunoblotting using JAK2 antibody. (D) Same as in (C) except that wt or mutant JAK2 prepared from γ2A stable clones were analyzed. (E) Wt JAK2 immunoprecipitated from starved or GM-CSF stimulated αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells were incubated with or without recombinant CK2, before they were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in (A). (F) Wt or mutant JAK2 immunoprecipitated from γ2A stable clones were analyzed as described in (E). Bottom panels of (C‒F) show the quantification results (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

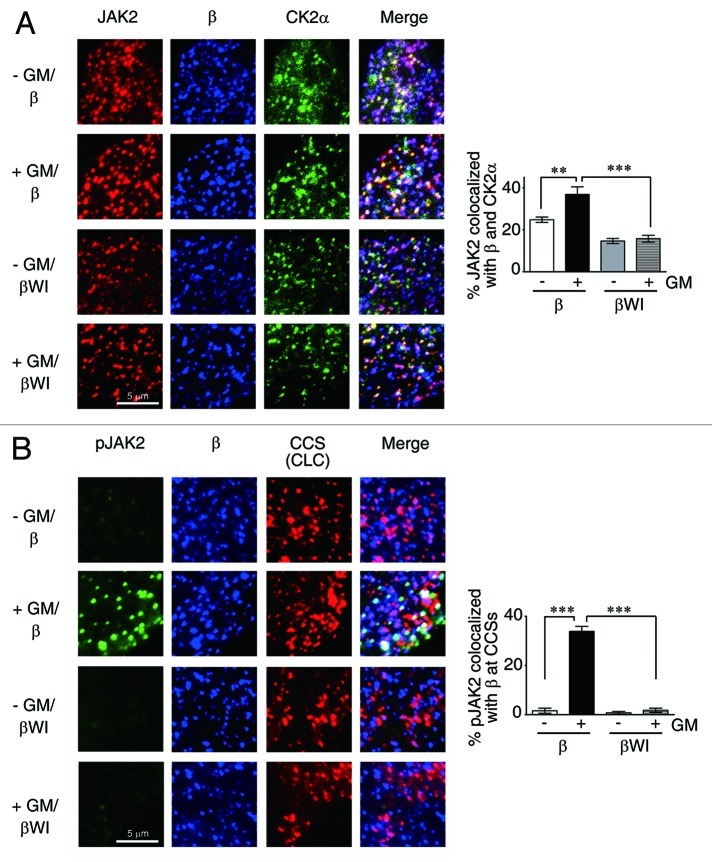

Ligand-induced conformational change is required for wt but not oncogenic JAK2 to be activated by CK2

Next, we explored why CK2-mediated activation of wt JAK2 is ligand-dependent. One possible scenario is that, to become accessible to CCS-localized CK2, wt JAK2 needs to undergo a ligand-dependent conformational change at CCSs. To examine this possibility, we performed a limited proteinase K digestion analysis to compare the proteinase K sensitivity of wt JAK2 immunoprecipitated from cells with or without ligand stimulation. As shown in Figure 9C, JAK2 from ligand-stimulated αβ-Ba/F3 cells consistently manifested a lower sensitivity to proteinase K compared with JAK2 from ligand-starved αβ-Ba/F3 cells, suggesting that JAK2 from these two sources indeed manifests distinct conformations. Intriguingly, JAK2V617F immunoprecipitated from γ2A cells stably expressing the V617F mutant (γ2A/JAK2V617F) also consistently manifested lower sensitivity to proteinase K than wt JAK2 immunoprecipitated from γ2A cells stably expressing the wt protein (γ2A/JAK2) (Fig. 9D), suggesting that JAK2V617F in the γ2A/JAK2V617F cells may adopt a conformation mimicking that of the wt protein in ligand stimulated αβ-Ba/F3 cells. Next, we examined whether ligand treatment would indeed switch CCS-localized JAK2 into a conformation that is more accessible to CK2 for activation. We thus performed an in vitro JAK2 activation assay using recombinant CK2 and JAK2 immunoprecipitated from αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells with or without prior ligand treatment. As shown in Figure 9E, none of the JAK2 immunoprecipitated from ligand-deprived αβ-Ba/F3 or from cells (αβWI-Ba/F3) whose JAK2 failed to be recruited to CCSs could be detected on the immunoblot by an active form specific antibody [anti-pJAK2 (Y1007/1008)] (lanes 1, 5 and 6). Further CK2 treatment still could not activate JAK2 from these three groups (lanes 3, 7 and 8). In contrast, a small fraction of JAK2 immunoprecipitated from ligand-stimulated αβ-Ba/F3 cells was already activated (lane 2) (likely due to the effect of endogenous CK2). Subsequent CK2 treatment further increased the active-form population (compare lanes 2 and 4), suggesting that ligand treatment indeed “transforms” CCS-localized JAK2 into a CK2-accessible conformation. We next performed a similar assay using wt or mutant JAK2 prepared from γ2A /JAK2 or γ2A/JAK2V617F cells. Consistent with the result shown in Figure 9D, JAK2V617F but not the wt protein manifested a feature that was very similar to JAK2 immunoprecipitated from ligand-stimulated αβ-Ba/F3 cells; i.e., a low fraction of JAK2V617F was already in an active configuration (Fig. 9F, lane 2) and subsequent CK2 treatment further increased the percentage of such population (Fig. 9F, lane 4 vs lane 2).

Discussion

Receptors and ligands can be internalized from the cell surface by clathrin-dependent or lipid raft-dependent pathways.37 Lipid rafts and/or caveolae have been shown to serve as platforms at plasma membrane for dynamic assembly of a variety of signaling complexes, including toll-like receptors, neurotransmitter receptors and immunological receptors (reviewed in refs. 38‒40). However, whether CCSs can also serve as signaling activation platforms remain elusive, albeit earlier studies demonstrated that clathrin is required for some cytokine receptors, such as the IFNα- receptor in mammals or the IL-6R-like receptor Dome in flies to activate the JAK/STAT signals.41,42 In this study, we provide several lines of evidence to support that CCS is one signaling platform for GMR to activate JAK2. It has been reported that, unlike the dynamin K44A mutant, which only blocks the membrane constriction step during CCV formation, dynasore blocks an additional step which results into the accumulation of the U-shaped, half-formed pits.43 The opposing results from experiments using these two dynamin inhibitors (Figs. 2D and 4H) further suggest that GMR-mediated JAK2 activation likely occurs at the stage when CCPs or clathrin-coated plagues are fully formed but before they are ready to bud off the membrane. A number of studies showed that receptor clustering, ligand/receptor binding and recruitment of different adaptors by receptor could modulate the CCP initiation and maturation.44-46 Since disruption of the CCS assembly by CHC and ITSN2 knockdown did not affect GMRβ clustering (Fig. 7A), it would be interesting to determine whether GMRβ clustering would also affect CCS initiation and/or maturation.

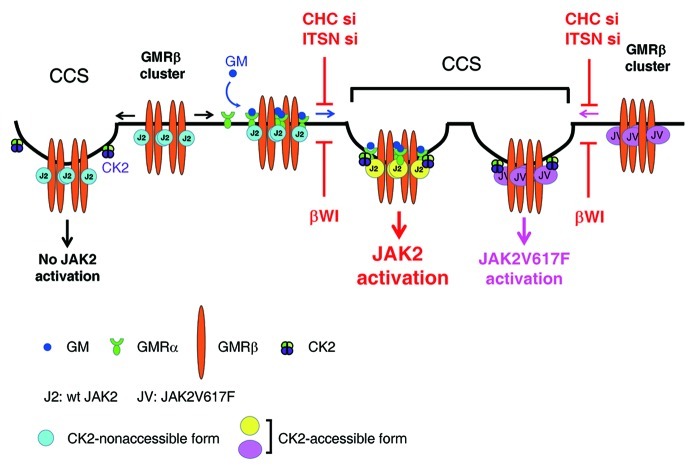

In this study, we also demonstrate that ligand stimulation, localization of GMR to CCSs and the CK2 activity are all required for JAK2 to be fully activated. Considering the fact that majority of CCSs (~45%) are equipped with CK2, and that a large fraction of JAK2 (~20%) are already pre-associated with GMRβ at CCSs prior to ligand stimulation, we propose a model to illustrate how JAK2 may be activated upon ligand binding to the GMR complex. In this model (Fig. 10), in the absence of ligand, JAK2 that is pre-associated with GMRβ at CCSs can’t respond to CK2 activation, likely due to its “locked” conformation that is not accessible to CK2. In contrast, in the presence of ligand, upon liganded-GMRα binding to CCS-localized GMRβ, those JAK2 that are pre-associated with GMRβ at CCSs are switched to an “open” conformation that can respond to CK2 activation. On the other hand, except that ligand stimulation is dispensable, both GMR localization to CCSs and the CK2 activity are also required for the activation of JAK2V617F in GMRβ-expressing cells. It is possible that, in the absence of ligand, the V617F mutation has rendered GMRβ-bound mutant JAK2 to adopt an “open” conformation mimicking that of wt JAK2 situated in the context of a liganded GMR complex and can thus respond to CK2 activation autonomously. It’s not clear how CK2 can trigger JAK2 activation. One possibility is that CK2, via its Ser/Thr or even Tyr kinase activity,47 phosphoryates JAK2 at one or multiple sites that are essential for the activation of the tyrosine kinase activity of JAK2. Such possibility is supported by one recent finding showing that CK2 forms a complex with JAK2 in vivo and can directly phosphorylate JAK2 in vitro, albeit the phosphorylation sites remain unclear.29 On the other hand, we also noticed that JAK2V617F in γ2A/V617F cells that did not contain GMRβ was already in a conformation that could respond to CK2 activation (Fig. 9F). One likely explanation is that in this cell system JAK2V617F can be co-recruited to CCSs via other cytokine receptor(s), such as the interferon-γ receptor.48 More experiments are required to address these issues.

Figure 10. Model for CK2-dependent, receptor-mediated activation of wt and the V617F mutant of JAK2 at CCSs. (see text for details).

We noticed that only ~35% of activated JAK2 was co-localized with GMRβ at CCSs upon ligand stimulation. Several possibilities may account for this result. First, all JAK2 are initially activated at a non-CCS location, but are subsequently partially relocated to CCS. Second, GMR-mediated JAK2 activation occurs at both CCSs and other cellular locations. Third, JAK2 can only be activated by the GMR complex at CCSs. However, JAK2 activated at such location is only transiently associated with CCSs and is quickly translocated to other cellular locations (the hit and run model). The first possibility would predict that neither MDC49 nor dynasore43 would exert any inhibitory effect on GMR-mediated JAK2 activation, but the experimental results (Fig. 2D and E) did not support such prediction. The second possibility is also less likely, as the observed inhibitory effect of MDC or dynasore was much more than that as predicted. The third possibility (the hit and run model) is likely the case and remains to be tested.

Another novel finding here is that, irrespective of the presence or absence of ligand, surface GMRβ exits as a cluster with a size similar to that of CCPs. Given that a large fraction of surface GMRβ (~20–30%) are co-localized with CCP components and such association is critical for receptor signaling, it is tempting to speculate that this pucta-like structure may serve as a platform to gather all required components, e.g., ligand-bound GMRα and CK2, to activate GMRβ-associated JAK2. Due to the technical restraint of the super resolution system used in this study, we were unable to precisely position the receptor molecules, which precluded us from distinguishing various forms of GMRβ, such as those in the so-called homodimer, hexamer or dodecamer structures.9 Such technical restraint may also explain why the cluster size and shape of GMRβ is quite similar irrespective of the presence or absence of ligand.

In this study, we noticed that ~10% of the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ (~50% of the wt level) could still be localized to CCSs. As yet, such mutant had lost nearly all ability to activate JAK2 in response to ligand stimulation (Figs. 3F and 9E), albeit its basal binding affinity to JAK2 was not changed. This result suggests that, other than inhibiting GMRβ-ITSN2 interaction and receptor endocytosis, the WI/AA mutation may also affect the accessibility of JAK2 to CCS-localized CK2 upon ligand stimulation. More experiments would be required to address this possibility. On the other hand, earlier studies demonstrated that mutation of the tryptophan residue in the Box 1 region of the erythropoietin receptor, i.e., the W258A mutation50 or in the gp130 subunit of the IL-6 receptor, i.e., the W652A mutation,51 impaired cytokine-induced JAK activation without affecting the binding affinity of JAK to their unliganded receptors. Although the underlying mechanism for the latter two cases is not clear, it is possible that such defects may share some features similar to that identified here for the WI/AA mutant of GMRβ.

In conclusion, this study reveals a novel functional role of CCSs in GM-CSF signaling and the oncogenesis of JAK2V617F. Identification of discrete steps of JAK2 activation may unravel novel targets for treating diseases involving abnormal JAK2 activation.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid DNA

All GMRβ deletion mutants were constructed by a PCR-based method to create a Pml I site in the 5' end and a stop codon (Not I linker) in its 3' end. After double digestion with Pml I and Not I, the digested PCR product was used to replace the Pml I/ Not I insert of pCDNA3-GMRβ. pGMRα-CFP, and pGMRβ-paGFP are pCDNA3 vector-based expression vectors expressing the GMRα-CFP, and GMRβ-photo-activatable GFP fusion proteins, respectively. pGMRβ-paGFP was constructed by PCR amplifying the coding region for the photo-activatable GFP from the pcDNA3.1/Zeo-paGFP vector (kindly provided by Dr. Chin-Yin Tai, Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica) and inserting the PCR fragment in-frame into the C terminus of the GMRβ cDNA cloned in pCDNA3-GMRβ. Bacterial expression vectors expressing His-tagged wt-β Box I+II and βWI Box I+II or GST-tagged sub-domains of ITSN2 (GST-A to GST-D) were all constructed by cloning respective cDNA fragment into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pGEX-2T vector. MSCV-mJAK2-IRES-GFP and MSCV-mJAK2 V617F-IRES-GFP plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Ross Levine (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Institute). HA-tagged hITSN2L and hITSN2s plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Susana de la Luna (Center for Genomic Regulation, University Pompeu Fabra). pEGFP-CK2α was kindly provided by Dr. Julio C. Tapia (Cell Transformation Laboratory, Program of Cellular and Molecular Biology, ICBM, Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile). The hITSN2L-EGFP expression vector was derived from the hITSN2L-mCherry expression vector, which was constructed by ligating the full-length hITSN2L cDNA into BglII/BamHI digested Cherry-LacRep (Addgene). The constructs expressing CLC-RFP, GFP-wt Dynamin I and GFP-K44A Dynamin I fusion proteins were also purchased from Addgene.

Cell lines

HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biological Industaries). HEL cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 55 µM β-mercaptoethanol. Ba/F3 cells were cultured in the same medium as HEL cells but with additional supplement of 10% WEHI-3B conditioned medium as a source of IL-3. αβ- or αβWI-Ba/F3 cells were maintained in the same medium as that used for parental Ba/F3 cells, except that the culture medium was supplemented with G418 (200 μg/ml) and hygromycin B (200 µg/ml). γ2A/JAK2 and γ2A/JAK2V617F stable clones were established by transfecting γ2A cells with MSCV-JAK2-IRES-GFP or MSCV-JAK2V617F-IRES-GFP vectors, followed by sorting out GFP-positive cells by flow cytometry. These cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-GMRα (C-18; H-120), anti-GMRβ (S-16;1C1), anti-pJAK2 (Y1007/1008, SC-21870-R) and anti-STAT5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-JAK2, anti-pJAK2 (Y1008, #8082), anti-pSTAT5 (Tyr694), anti-pAKT (Ser473), anti-AKT, anti-pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and anti-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology); anti-pY (Millipore); anti-clathrin heavy chain mouse mAb (Calbiochem); anti-Shc (BD Transduction Laboratories™); anti-HA (Roche); anti-His and anti-GST (Yao-Hong technology, Inc.); anti-mouse ITSN1 (BD Transduction Laboratories™); Cy5- (A10524) or Alexa Flour® 633-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies F(ab’)2 (A21053) and Alexa Flour® 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies F(ab’)2 (A11070) (Invitrogen).

Other reagents

Other reagents used in this study include: specific Stealth RNAi™ siRNA against clathrin heavy chain [human, 5'GAGUGCUUUGGAGCUUGUCUGUUUA3' (HSS174637); mouse, siRNA1, 5'CCAAGUAUGGUUAUAUUCACCUCUA3' (MSS228221)], siRNA2, 5'AUUAGCUGACAGCAUGGCUCUGAGG3' (MSS228223) and intersectin-2 [human, siRNA1, 5'GACGUUGAUGGUGAUGGACAGCUAA3' (HSS121345), siRNA2, 5'UUCAAGGGCUAACUGCUGUGUGUUG3' (HSS181730); mouse, siRNA1, 5'GGCAGUUCCUCAGCCUUCAAGAUUA3' (MSS277044)], siRNA2, 5'GCCAUUGCCUCCAGUUGCACCUAUA3' (MSS208962) (Invitrogen) (Unless otherwise specified, all siRNA treatment experiments mentioned in the text for clathrin heavy chain or intersection-2 were using the combination of siRNA1 and siRNA2); monodansylcadaverine (MDC), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), dynasore and 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBB), and Proteinase K (all from Sigma). Recombinant CK2 supplemented with kinase buffer was purchased from New England BioLabs Inc. Recombinant His-tagged wt-β Box I+II and βWI Box I+II proteins and GST-tagged proteins containing various ITSN2 sub-domains (GST-A- to GST-D) were all produced in bacteria strain JM109.

Imaging

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) images shown in Figures 1D, 4A, 7 and 8 were taken with a Laser TIRF 3 microscope (Carl Zeiss) using an α Plan-Apochromat 100×/1.57 Oil-HI DIC Corr objective at a 150 nm penetration depth in MEM Alpha medium (Gibco) at 37°C and acquired by the AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss). Super-resolution images shown in Figure 1A were acquired using direct STORM (dSTORM) scheme essentially as previously described31 with some modifications. Briefly, the total internal reflection fluorescence image stacks were measured via an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX71, Olympus) equipped with a dual-view system (DV2, Photometrics) and an electron multiplying charge-coupled device (EM CCD, iXon DU-897E, Andor) to measure two-color fluorescence images simultaneously. The excitation light source were a solid state laser (Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Tech) with a wavelength of 473 nm and a helium-neon laser (Melles Griot) with a wavelength of 632.8 nm. The excitation and emission filter was a multi-band pass filter (FF01–390/482/563/640, Semrock). The cut-off of a quad-edge dichroic mirror was at 405, 488, 561 and 635 nm (Di01-R405/488/561/635, Semrock). The emission filters of the dual-view system were band-pass filters at 525/45 nm and 692/40 nm (FF01–525/45–25, FF01–692/40–25, Semrock). The imaging field was magnified using an oil objective (Olympus) with a magnification of 100 and an optical lens with a magnification of 1.6. The effective pixel size was around 109.2 nm. Before conducting the super-resolution imaging, a buffer containing 100 mM of β-mercaptoethylamine (MEA) was added to the sample. The samples were first illuminated with laser at full power until most of the dyes were converted to the dark state and the blinking of dye molecules could be observed. The fluorescence images were then recorded with an integration time of 50 ms and an EM gain of 250. Typically 20,000 frames of images were recorded for each experiment. The fluorescence image stacks were used to determine the location of individual dye using the localization algorithm of dSTORM. The super-resolution images were reconstructed by plotting the center position of each individual molecules and the width was determined by the accuracy of localization.

To estimate the receptor number in the super resolution images, the localized events with separation distance less than 10 nm were considered as the signal coming from the same protein as previously described.31 Based on the (x, y) coordinate of each observable protein, the pair distance between every two proteins was calculated and the histogram of these pair distances with distance less than 500 nm was plotted. The size of cluster was calculated by measuring the pair distance at which the pair distance distribution fell below 10% of its integrated value. Two color dSTORM was used to measure the size of GMRβ and CHC clusters simultaneously. Based on single molecule localization, it is possible to quantify protein number within a unique subcellular structure revealed by super-resolution (SR) imaging. To achieve this goal, we must avoid repeatedly counting the same protein due to the stochastic blinking behavior of the fluorophores. Since the size of antibody and the localization accuracy is around 10 nm, we treated any localization event with pair-correlation distance less than 10 nm to be the signals from the same protein.31 It has been demonstrated that, by analyzing the pair-correlation function of the SR images, individual protein and cluster of proteins can be distinguished.52 Here, we employed a similar algorism as that reported by Sengupta et al. to analyze the SR images of GMRβ and CHC clusters and calculate the number of proteins within each cluster. Taking account of the labeling efficiency and accidental overlapping of two proteins, the estimated receptor numbers reported here served as the lower bound of the receptor numbers. By analyzing hundreds of CCPs, the uncertainty in the receptor numbers in each coated pit can be minimized.

Sample preparation for TIRF and dSTORM imaging

HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP, GMRβ along with other fluorescent proteins (CLC-RFP, ITSN2-EGFP or CK2α-GFP) as indicated in each figure were pre-cooled at 4°C for 30 min and then stained with anti-GMRβ mouse monoclonal antibody. After 30 min staining at 4°C, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and further stained with Cy5- or Alexa Flour® 633-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. For visualizing endogenous JAK2 (or pJAK2) together with GMRα-CFP, GMRβ and CLC-RFP (or CK2α-GFP) (Figs. 7 and 8), HeLa cells transiently co-expressing these molecules were processed essentially as described above except that, after the fixation step, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% triton-X100 before they were further stained with JAK2 (or pJAK2) and appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. When visualized under the TIRF microscope, cells with CFP signals (expressing GMRα-CFP) were selected for analysis of the distribution of other proteins of interest. For the imaging system shown in Figure 1A, HeLa cells transiently co-expressing GMRα-CFP and GMRβ were first stained with mouse anti-GMRβ antibody, and then fixed, permeabilized and stained with rabbit anti-CHC antibody. After that, these primary antibody-stained cells were probed with Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse and Alexa Flour® 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. To acquire dSTORM images of these cells, GMRα-CFP-expressing cells were first identified using the Leica TIRF microscope (Leica AM TIRF MC, Leica), and then based on their XY coordinates on the slide, they were further analyzed by the inverted fluorescence microscope (IX71, Olympus).

Analysis and quantification of the receptor internalization assay

Unless otherwise specified, all receptor internalization assays were performed as described below. Cells to be analyzed were pre-cooled at 4°C for 30 min and then stained with anti-GMRα and anti-GMRβ antibodies for additional 30 min at 4°C. To initiate receptor endocytosis, antibody-labeled cells were transferred to 37°C. At various time points after receptor endocytosis had started, cells were immediately shifted back to 4°C, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS and further labeled with Alexa flour® 488-conjugated anti-rabbit and Alexa flour® 555-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies to detect the GMR α and β subunits, respectively. The extent of receptor internalization was analyzed by confocal microscopy using LSM 510 META, LSM 710 or LSM780 laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss) and quantified by using the MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). The percentage of GMRβ (wt or mutant) that had undergone endocytosis was calculated as follows: (intensity of antibody-labeled molecules within an intracellular location/ intensity of all labeled receptors) × 100%. Alternatively, the receptor internalization ability in suspension cells was measured using flow cytometry. For the latter experiment, cells were processed essentially the same as that described above except that after shifting back to 4°C to stop receptor endocytosis; the remaining amounts of antibody-labeled GMRβ that still resided at the cell surface were analyzed by flow cytometry. The fluorescent intensity of antibody-labeled GMRβ on cells that had never been shifted to 37°C for the internalization assay was taken as total amounts of GMRβ at the cell surface.

In vitro JAK2 activation assay using recombinant CK2

JAK2 or JAK2V617F proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates of γ2A/ JAK2, γ2A/JAK2V617F, cytokine-deprived or hGM-CSF (0.5 ng/ml) stimulated αβ-Ba/F3 or αβWI-Ba/F3 cell lines with anti-JAK2 antibody. The immune complexes were subsequently incubated with or without recombinant CK2 at room temperature for 1 h, followed by immunoblotting analysis using antibody specific to phospho-JAK2 (Y1007/Y1008) and total JAK2.

Quantification of the activation extent of signaling molecules

The activation (phosphorylation) extent of JAK2, AKT, STAT5 and ERK in cells under various treatments was presented as a relative ratio of the intensity of the phosphorylation form vs that of total protein of a given molecule. The highest ratio of a given molecule at a particular time point following GM-CSF re-stimulation in each independent experiment was set as 100.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with either Student’s t tests (for comparison between two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Tukey’s post tests, for comparison among multiple experimental groups) using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sandra L. Schmid for critical reading of this manuscript; Drs. Ross Levine, Susana de la Luna, Julio C. Tapia and George Stark for providing JAK2V617F-IRES-GFP, hITSN2, GFP-CK2α plasmids and γ2A cell line, respectively. We also want to thank Tzu-Wen Tai, Cheng-Yen Huang and Hua-Man Hsu for their technical supports. This study was supported in part by an intramural fund from Academia Sinica and by a grant (NSC98–2320-B-001–006-MY3) from the National Science Council of Taiwan to J.J.Y.Y.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CCPs

clathrin-coated pits

- CCSs

clathrin-coated structures

- CCVs

clathrin-coated vesicles

- CHC

clathrin heavy chain

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- CLC

clathrin light chain

- CME

clathrin-mediated endocytosis

- GMRα and GMRβ

the α and β subunits of the GM-CSF receptor, respectively

- ITSN

intersectin

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Editorial Note

This paper was accepted based in part on peer-reviews obtained from another journal.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21920

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21920

References

- 1.Gearing DP, King JA, Gough NM, Nicola NA. Expression cloning of a receptor for human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. EMBO J. 1989;8:3667–76. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guthridge MA, Stomski FC, Thomas D, Woodcock JM, Bagley CJ, Berndt MC, et al. Mechanism of activation of the GM-CSF, IL-3, and IL-5 family of receptors. Stem Cells. 1998;16:301–13. doi: 10.1002/stem.160301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashida K, Kitamura T, Gorman DM, Arai K, Yokota T, Miyajima A. Molecular cloning of a second subunit of the receptor for human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF): reconstitution of a high-affinity GM-CSF receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9655–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muto A, Watanabe S, Miyajima A, Yokota T, Arai K. High affinity chimeric human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor carrying the cytoplasmic domain of the beta subunit but not the alpha subunit transduces growth promoting signals in Ba/F3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;208:368–75. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakamaki K, Miyajima I, Kitamura T, Miyajima A. Critical cytoplasmic domains of the common beta subunit of the human GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 receptors for growth signal transduction and tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1992;11:3541–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brizzi MF, Zini MG, Aronica MG, Blechman JM, Yarden Y, Pegoraro L. Convergence of signaling by interleukin-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and mast cell growth factor on JAK2 tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31680–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lilly MB, Zemskova M, Frankel AE, Salo J, Kraft AS. Distinct domains of the human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor alpha subunit mediate activation of Jak/Stat signaling and differentiation. Blood. 2001;97:1662–70. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.6.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quelle FW, Sato N, Witthuhn BA, Inhorn RC, Eder M, Miyajima A, et al. JAK2 associates with the beta c chain of the receptor for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and its activation requires the membrane-proximal region. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4335–41. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen G, Hercus TR, McClure BJ, Stomski FC, Dottore M, Powell J, et al. The structure of the GM-CSF receptor complex reveals a distinct mode of cytokine receptor activation. Cell. 2008;134:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindauer K, Loerting T, Liedl KR, Kroemer RT. Prediction of the structure of human Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) comprising the two carboxy-terminal domains reveals a mechanism for autoregulation. Protein Eng. 2001;14:27–37. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo H, Rose P, Barber D, Hanratty WP, Lee S, Roberts TM, et al. Mutation in the Jak kinase JH2 domain hyperactivates Drosophila and mammalian Jak-Stat pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1562–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng J, Witthuhn BA, Matsuda T, Kohlhuber F, Kerr IM, Ihle JN. Activation of Jak2 catalytic activity requires phosphorylation of Y1007 in the kinase activation loop. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2497–501. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders is not just another kinase. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1053–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.8.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell PJ, Green AR. The myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2452–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, et al. Cancer Genome Project Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365:1054–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1779–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao R, Xing S, Li Z, Fu X, Li Q, Krantz SB, et al. Identification of an acquired JAK2 mutation in polycythemia vera. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22788–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500138200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones AV, Kreil S, Zoi K, Waghorn K, Curtis C, Zhang L, et al. Widespread occurrence of the JAK2 V617F mutation in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2005;106:2162–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pradhan A, Lambert QT, Reuther GW. Transformation of hematopoietic cells and activation of JAK2-V617F by IL-27R, a component of a heterodimeric type I cytokine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18502–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702388104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pradhan A, Lambert QT, Griner LN, Reuther GW. Activation of JAK2-V617F by components of heterodimeric cytokine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16651–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuther GW. JAK2 activation in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a potential role for heterodimeric receptors. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:714–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsyba L, Nikolaienko O, Dergai O, Dergai M, Novokhatska O, Skrypkina I, et al. Intersectin multidomain adaptor proteins: regulation of functional diversity. Gene. 2011;473:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henne WM, Boucrot E, Meinecke M, Evergren E, Vallis Y, Mittal R, et al. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 2010;328:1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett RM, Colnaghi R, Wheatley SP. Threonine 48 in the BIR domain of survivin is critical to its mitotic and anti-apoptotic activities and can be phosphorylated by CK2 in vitro. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:538–48. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham KC, Litchfield DW. The regulatory beta subunit of protein kinase CK2 mediates formation of tetrameric CK2 complexes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5003–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korolchuk VI, Banting G. CK2 and GAK/auxilin2 are major protein kinases in clathrin-coated vesicles. Traffic. 2002;3:428–39. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y, Qin H, Frank SJ, Deng L, Litchfield DW, Tefferi A, et al. A CK2-dependent mechanism for activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Blood. 2011;118:156–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Linde S, Löschberger A, Klein T, Heidbreder M, Wolter S, Heilemann M, et al. Direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy with standard fluorescent probes. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:991–1009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chien FC, Kuo CW, Yang ZH, Chueh DY, Chen PL. Exploring the formation of focal adhesions on patterned surfaces using super-resolution imaging. Small. 2011;7:2906–13. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones SA, Shim SH, He J, Zhuang X. Fast, three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of live cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirchhausen T. Imaging endocytic clathrin structures in living cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damke H, Baba T, Warnock DE, Schmid SL. Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic coated vesicle formation. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:915–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu X, Levine R, Tong W, Wernig G, Pikman Y, Zarnegar S, et al. Expression of a homodimeric type I cytokine receptor is required for JAK2V617F-mediated transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18962–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korolchuk VI, Cozier G, Banting G. Regulation of CK2 activity by phosphatidylinositol phosphates. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40796–801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schütze S, Tchikov V, Schneider-Brachert W. Regulation of TNFR1 and CD95 signalling by receptor compartmentalization. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:655–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fantini J, Barrantes FJ. Sphingolipid/cholesterol regulation of neurotransmitter receptor conformation and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2345–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fessler MB, Parks JS. Intracellular lipid flux and membrane microdomains as organizing principles in inflammatory cell signaling. J Immunol. 2011;187:1529–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jury EC, Flores-Borja F, Kabouridis PS. Lipid rafts in T cell signalling and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devergne O, Ghiglione C, Noselli S. The endocytic control of JAK/STAT signalling in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3457–64. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchetti M, Monier MN, Fradagrada A, Mitchell K, Baychelier F, Eid P, et al. Stat-mediated signaling induced by type I and type II interferons (IFNs) is differentially controlled through lipid microdomain association and clathrin-dependent endocytosis of IFN receptors. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2896–909. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–50. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu AP, Aguet F, Danuser G, Schmid SL. Local clustering of transferrin receptors promotes clathrin-coated pit initiation. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1381–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mettlen M, Loerke D, Yarar D, Danuser G, Schmid SL. Cargo- and adaptor-specific mechanisms regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:919–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M. Cargo regulates clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Cell. 2006;127:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vilk G, Weber JE, Turowec JP, Duncan JS, Wu C, Derksen DR, et al. Protein kinase CK2 catalyzes tyrosine phosphorylation in mammalian cells. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1942–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadir R, Lambert A, Lortat-Jacob H, Morel G. Caveolae and clathrin-coated vesicles: two possible internalization pathways for IFN-gamma and IFN-gamma receptor. Cytokine. 2001;14:19–26. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phonphok Y, Rosenthal KS. Stabilization of clathrin coated vesicles by amantadine, tromantadine and other hydrophobic amines. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:188–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80390-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Constantinescu SN, Huang LJ, Nam H, Lodish HF. The erythropoietin receptor cytosolic juxtamembrane domain contains an essential, precisely oriented, hydrophobic motif. Mol Cell. 2001;7:377–85. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00185-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haan C, Heinrich PC, Behrmann I. Structural requirements of the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp130 for its interaction with Janus kinase 1: the receptor is crucial for kinase activation. Biochem J. 2002;361:105–11. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sengupta P, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Skoko D, Renz M, Veatch SL, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Probing protein heterogeneity in the plasma membrane using PALM and pair correlation analysis. Nat Methods. 2011;8:969–75. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.