Abstract

In the event of a deliberate or accidental radiological emergency, the skin would likely receive substantial ionizing radiation (IR) poisoning which could negatively impact cellular proliferation, communication, and immune-regulation within the cutaneous microenvironment. Indeed, as we have previously shown, local IR exposure to the murine ear causes a reduction of two types of cutaneous dendritic cells (cDC), including interstitial DC (iDC) of the dermis and Langerhans cells (LC) of the epidermis, in a dose and time dependent manner. These APCs are critical regulators of skin homeostasis, immuno-surveillance, and the induction of T and B cell-mediated immunity as previously demonstrated using conditional cDC knockout mice. To mimic a radiological emergency, we developed a murine model of sub-lethal total body irradiation (TBI). Our data would suggest that TBI results in the reduction of cDC from the murine ear that was not due to a systemic response to IR as a loss was not observed in shielded ears. We further determined that this reduction was due, in part, to the up-regulation of the chemoattractant CCL21 on lymphatic vessels as well as CCR7 expressed on cDC. Migration as a potential mechanism was confirmed using CCR7−/− mice where cDC were not depleted following TBI. Finally, we demonstrated that the loss of cDC following TBI results in an impaired contact hypersensitivity (CHS) response to hapten by using a modified CHS protocol. Taken together, these data suggest that IR exposure may result in diminished immuno-surveillance in the skin, which could render the host more susceptible to pathogens.

Introduction

As evident by the recent nuclear disaster in Japan and threats of radiological warfare through the use of nuclear weapons or attack on nuclear power plants, it is imperative that effective medical countermeasures and emergency strategies be implemented to triage victims exposed to IR (1, 2). In these instances, the skin would likely receive substantial IR poisoning which, over the course of several days, could manifest into a form of cutaneous radiation syndrome (3) and lead to multi-organ failure (4). As skin is the largest organ of the human body and first line of defense against a hostile environment of biological, chemical, and physical traumas, further investigation into the mechanisms regulating IR-induced skin injury are needed so that we can properly mitigate the risk of cutaneous infection and subsequent damage to other organ systems.

Cutaneous dendritic cells (cDC), including interstitial DC (iDC) of the dermis and Langerhans cells (LC) of the epidermis, are members of a highly specialized, immuno-surveillant family known as antigen presenting cells that are critical for tissue homeostasis, the induction of immune tolerance, and the elicitation of protective immunity (5). Within the dermis, iDC can be distinguished from dermal macrophages by surface CD11c, CD205, and elevated MHC class II (MHC II) expression (6), whereas LC are the only DC present in the epidermis and therefore can be identified by CD207 alone (7). It is well established that in addition to steady state migration (8), cDC are mobilized and depleted from the skin in response to antigen acquisition as well as a variety of other pro-inflammatory stimuli (9, 10). Following signaling, cDC enter lymphatics and traffic to the draining lymph nodes to further initiate the appropriate adaptive immune response. Of critical importance for cDC migration and entry into draining lymphatics are the chemotactic ligand CCL21, made by lymphatic endothelial cells (11), and the corresponding receptor, CCR7, which is expressed on activated DC in the skin (12). Whereas mice deficient in CCL21 exhibit impaired cDC migration to draining lymph nodes (13), deletion of CCR7 completely abolishes cDC migration from the skin (12).

Similar to non-ionizing, ultra-violet radiation (UV) (14), we have previously shown that local IR exposure causes a dose and time dependent reduction of cDC from the mouse ear (15). Despite extensive studies investigating the UV-induced depletion of cDC and subsequent suppression of cell-mediated immunity within the skin, there are little data describing the immuno-modulatory effects of IR within the cutaneous microenvironment. Many of the existing references are largely descriptive and solely focus on the signs and symptoms following IR exposure without addressing the consequences on the immune system aside from complete blood count analyses. In addition, few studies have examined the cDC compartment and the immune response following sub-lethal total body irradiation (TBI) which would likely result after a radiological emergency (3). Although eloquent studies conducted by Merad et al. examining the long-term maintenance of cDC populations after complete bone marrow chimerism suggest that both LC (8) and, to a degree, iDC (6), were repopulated in situ by radio-resistant progenitor cells, little is known of the fate or functional relevance of cDC immediately after sub-lethal TBI.

Depending on mouse strain, the lethal dose at which 50 % of the animals die over the course of 30 days following TBI (LD50/30) is approximately 9 Gy whereas for humans the LD50/30 is believed to be between 3–4 Gy (16). Here, we describe a mouse model of sub-lethal, 6 Gy TBI that mimics skin exposure following a radiological emergency to examine the mechanism of the IR-induced partial depletion of cDC. Similar to local IR exposure of mouse ear, cDC were reduced following TBI and accumulated in the auricular draining lymph node (ADLN) over time. Our data would suggest that this TBI-induced migration is driven, in part by, CCL21 and CCR7 as mRNA expression for each was up-regulated after TBI. In addition, we detected a significant increase in CCL21 protein associated with LYVE-1 positive lymphatic endothelial cells following TBI relative to un-irradiated controls. Importantly, the requirement for CCR7 in this model was further supported by the retention of both iDC and LC populations within the dermis and epidermis of TBI exposed CCR7−/− mice, respectively. Finally, TBI results in an impaired cDC response to hapten challenge as measured by a modified contact hypersensitivity (CHS) assay. Taken together, IR exposure appears to induce the migration of cDC which may limit skin immuno-surveillance and render the host more susceptible to pathogen entry.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male and female C57BL6 albino hairless mice (hairless mice) were used for experiments described in figures 1–5 as well as figure 7 and were provided by Dr. Alice Pentland in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. This colony was bred and maintained by our laboratory. The experiment in figure 6 was carried out using female B6.129P2(C)-Ccr7tm1Rfor/J (CCR7−/−) mice which are also of the C57BL/6 strain background. These mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All animal use protocols were approved by the University of Rochester’s University Committee on Animal Resources (UCAR).

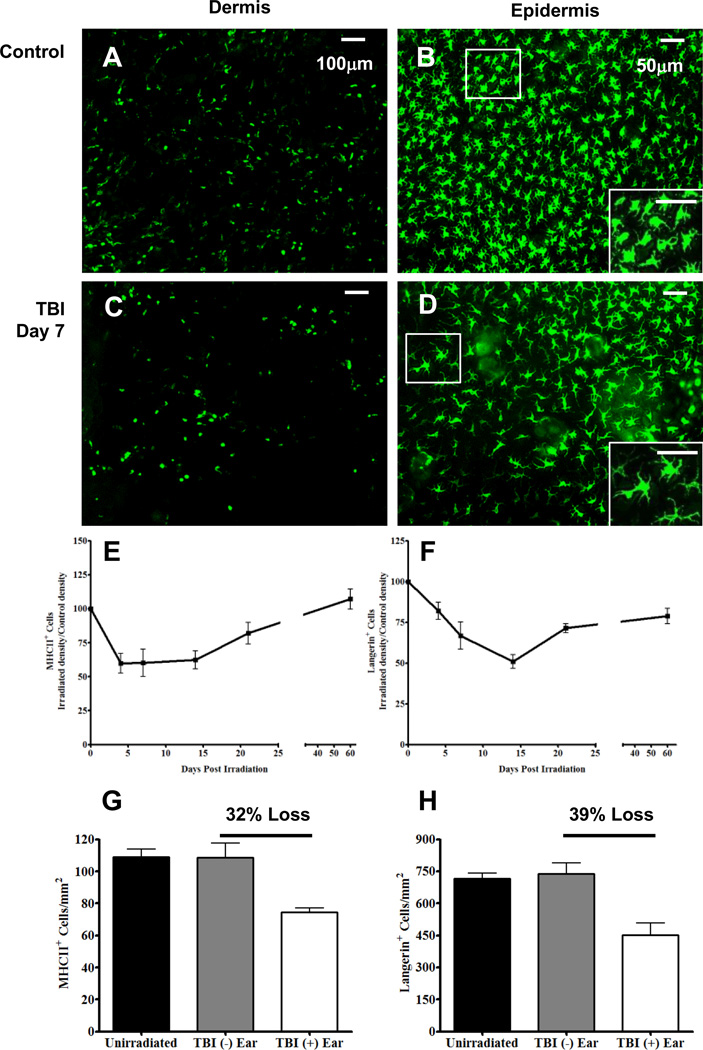

FIGURE 1. Exposure to TBI results in a partial depletion of iDC and LC in a time-dependent manner.

Fluorescence whole-mount microscopy images from un-irradiated mouse ear dermis (A), and epidermis (B) labeled with anti-MHC II and anti-Langerin, respectively. Dermal and epidermal images from day 7 post TBI are shown in images C and D, respectively, and were labeled with the same aforementioned antibodies. Using these images, irradiated ear densities were calculated and divided by non-irradiated control ear densities and multiplied by 100 to obtain normalized points for the MHC II+ (E) and Langerin+ cells (F). G and H, Quantification of MHC II+ and Langerin+ cells in mouse ear dermis and epidermis, respectively, from un-irradiated mice (black bar) or mice receiving TBI (TBI + ear) (white bar) and the shielded contralateral ear (TBI − ear) (gray bar). Images and data in G and H are from day 7 post TBI. Percent depletion was calculated using the following equation: % Depletion = 100 – ([TBI (+) ear / TBI (−) Ear] × 100). n = 6 mice per time point +/− SEM and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. Scale bars are 100 and 50 µm for dermal and epidermal images, respectively.

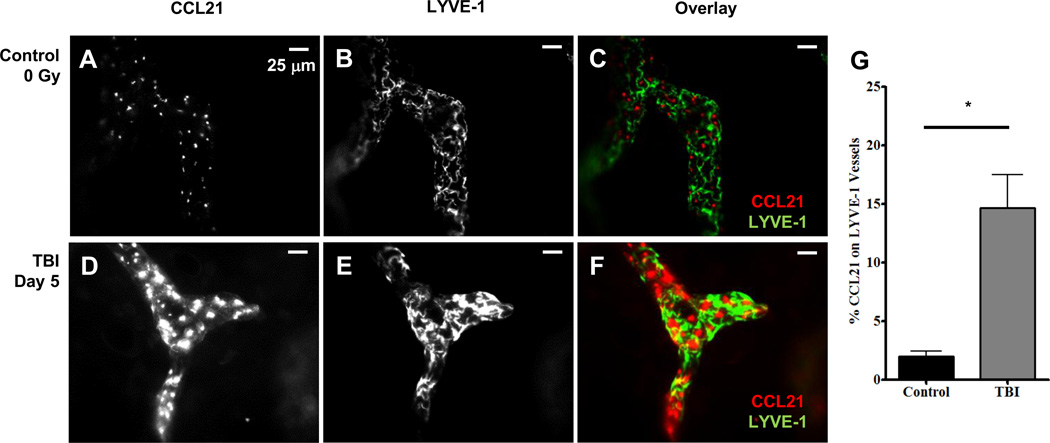

FIGURE 5. TBI causes an up-regulation of the CCL21 protein in LVYE-1 lymphatic vessels.

A–C, Fluorescence whole-mount images from an un-irradiated mouse ear dermis labeled with CCL21 (A) and LYVE-1 lymphatic vessels (B) and overlaid in C. D-F, Fluorescence whole-mount images from a day 5 post TBI mouse ear dermis labeled with CCL21 (D) and LYVE-1 (E) and overlaid in F. I, the percentage of CCL21 area on LYVE-1 lymphatic vessels is shown. n = 6 mice per group +/− SEM, and statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired t test with Welch correction. * = p < 0.01. Scale bar is 25 µm.

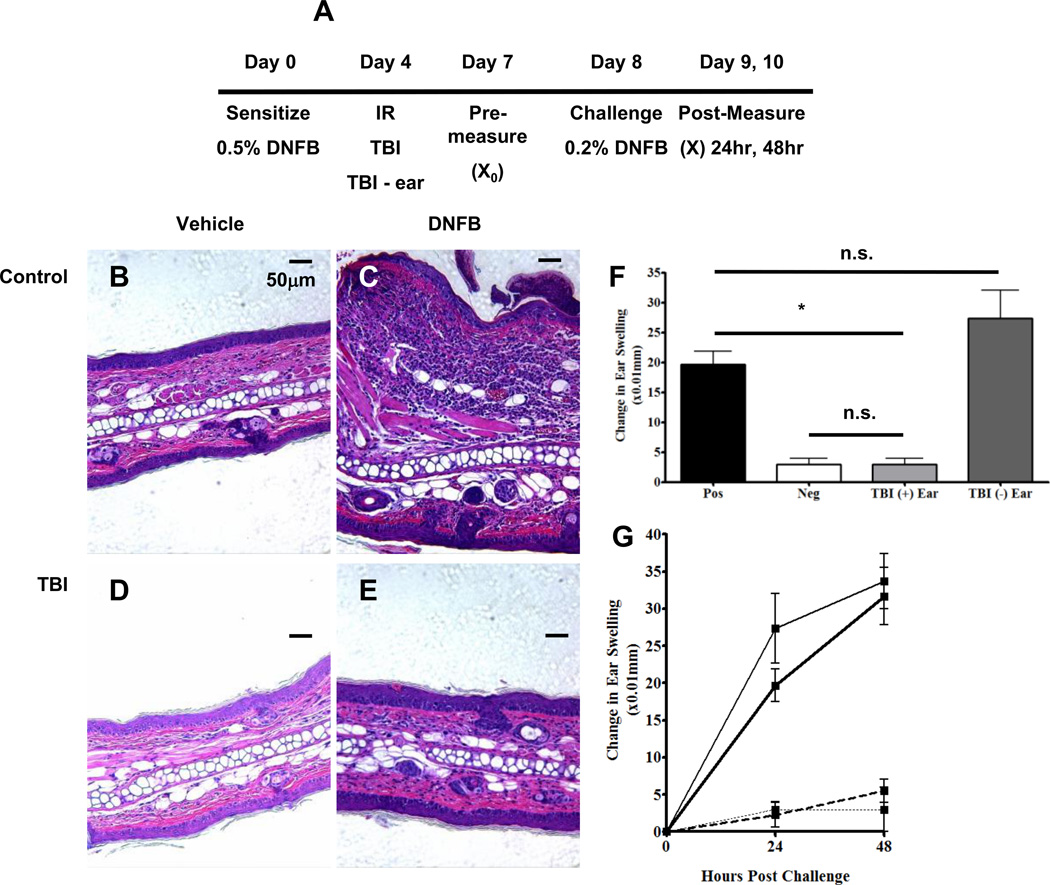

FIGURE 7. Partial depletion of cDC following TBI impairs the contact hypersensitivity response to hapten whereas mice exposed to − ear respond similar to positive controls.

A, Experimental scheme for the TBI-induced reduction of cDC in a CHS assay. Mice were sensitized, irradiated, and challenged as depicted above. B – E, Un-irradiated (B and C) and TBI mouse ear sections (D and E) 48 hours following vehicle (B and D) and DNFB (C and E) challenge. All ear sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. F, Ear swelling twenty-four hours following challenge (F) and over time (G) was measured in the following groups: positive control (black bar, heavy black line); negative control (white bar, dotted black line); TBI + ear (grey bar, hashed line) and TBI − ear (charcoal bar, thin black line). Change in Ear Thickness = (X − X0) where X0 is the pre-challenge measurement and X is the post challenge measurement. n = 4 mice per group and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. * = p < 0.01. Scale bar is 50 µm.

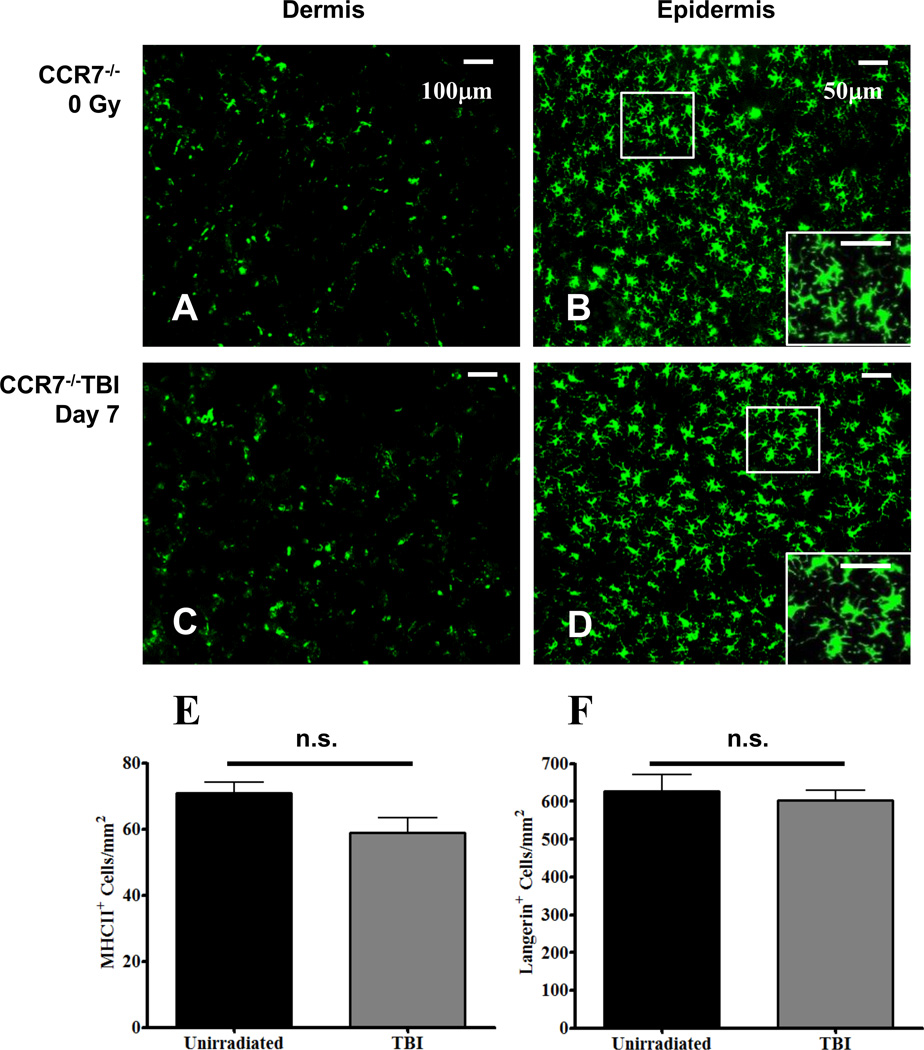

FIGURE 6. CCR7 is required for TBI-induced migration of cDC.

Fluorescence whole-mount microscopy images from un-irradiated CCR7−/− mouse ear dermis (A), and epidermis (B) labeled with anti-MHC II and anti-Langerin, respectively. Dermal and epidermal images from day 7 post TBI are shown in images C and D, respectively, and were labeled with the same aforementioned antibodies. Using these images, MHC II+ (E) and Langerin+ cellular densities (F) were quantified from un-irradiated (black bars) and irradiated (grey bars) CCR7−/− mice. n = 6 mice per group +/− SEM, and statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired t test with Welch correction.

Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies

Fc Block was purchased from BD Biosciences. Allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-mouse MHC II (I-A/I-E), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated internal anti-mouse Langerin (CD207), PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c, APC-Cy7-conjugated anti-mouse CD45, PE-conjugated anti-mouse Ly-6G, and FITC-conjugated CD31 were purchased from eBioscience.

Reagents

The tribromoethanol anesthesia stock solution was prepared by dissolving 5 g of 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in 5 ml of 2-methyl-2-butanol (Sigma) with gentle heating. The anesthesia was diluted 1:40 in PBS and mice were injected intraperitoneally with 300µl of this dilution. Tetramethylrhodamine-5-(and-6)-isothiocyanate (TRITC) was prepared and applied to mouse ears as previously described (17) (Life Technologies Corporation).

Irradiation Protocol

The 3200 Curie sealed 137Cesium source operated at roughly 1.90 Gy/min was used for all irradiated samples. Gamma radiation was administered at doses ranging from 1–25 Gy and both total body irradiation (TBI) and single beam collimators were used for these studies. Mice receiving a TBI dose of 6 Gy were placed into a Plexiglas box designed to prevent vertical movement away from the radiological source and the TBI collimator was used. For those mice receiving local radiation, the single beam collimator was used and once under anesthesia, mice were placed into specially made jigs allowing for radiation exposure to one ear while the rest of the mouse (including the contralateral ear), remained shielded and unexposed to the radiation. The TBI − studies were performed in a similar fashion, however for these experiments the TBI collimator was used and the entire body except for one ear, was exposed to radiation while the single ear remained shielded and unexposed.

Tissue Removal and Processing

Ear removal

Mice were sacrificed according to UCAR approved protocol. The ears were then removed, split into dorsal and ventral halves with the aid of forceps, and placed into dishes of HBSS (Sigma) for dermal layer labeling.

Epidermal sheet processing

Following ear splitting, halves were floated in 0.5M ammonium thiocyanate (Sigma) at 37°C for 20 minutes to separate epidermal from dermal layers. The epidermal layer was then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (J.T. Baker) at room temperature for 15 minutes to permeabilize cells for 1.5 hours of intracellular labeling with PE-conjugated internal anti-Langerin (eBioscience), a concentration of 4 µg/ml.

Whole Mount Analysis and Conventional Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence labeling

Whole mount histology was performed on split ear samples as previously described (15). Briefly, samples approximately 12 mm by 10 mm by 0.5 mm in size were placed in 6 ml polypropylene tubes (BD Biosciences). Ear tissues were incubated with Fc Block (BD Biosciences) at 10 µg/ml in 200 µl of phosphate-bovine-azide solution (PBA) (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide) (Sigma) for 45 minutes. Following Fc Block, dermal samples were labeled with anti-MHC II-allophycocyanin (eBioscience) at 3 µg/ml and gently rocked at 4°C for 1.5 hours. Samples were washed once by adding 3 ml of PBA with gentle rotation at 4°C for 30 minutes. To control for nonspecific binding, anti-rat Ig isotype controls were used, and labeling was nonexistent. For anti-CCL21 labeling a modified protocol was followed. In brief, mouse ears were excised, split, and fixed in 1 % PFA for two hours at 4°C with gentle rocking. Next, samples were labeled with anti-LYVE-1-AlexaFluor 488 (R&D Systems, Inc.) at 0.5 ng/ml and goat-anti-mouse CCL21 primary antibody (R&D Systems, Inc.) at 5 µg/ml for two hours at 4°C with gentle rocking. Finally, samples were labeled with CCL21 secondary antibody, a Cy3-conjugated donkey-anti-goat IgG, at 5 µg/ml for two hours at 4°C with gentle rocking. All samples were labeled and blocked in PBS-Triton X-100 (0.3 % v/v) supplemented with 5% (v/v) normal donkey serum.

Conventional Fluorescence Microscopy

Whole mount analysis was performed using an Olympus BX40 conventional fluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc.,) and images were acquired using a Retiga 1300 camera (QImaging). Labeled samples were placed on a glass slide with a cover slip and 20 µl PBA added to wet the slide. The split ear sample selected for imaging was the ventral/inner ear half, as it had fewer densely packed cartilage cells within the hypodermal layer. The epidermal side was placed facing toward the coverslip and microscope objective. Ear tissue was then viewed using three fluorescence filter cubes (Chroma Technology Corp); APC cube - excitation filter D595/40× and emission filter D660/40m; PE Hg light source cube - excitation filter D546/10× and emission filter D580/30m. Images were obtained at a 10× magnification of the entire ear only if they met the following criteria: no cartilage cells, stray hairs, or debris within the field of view, and a full field of view away from the edges to avoid the nonspecific antibody-edge-effect. Bright field images were acquired first followed by fluorescence images. Images obtained under fluorescence were created using the extended depth of field tool within the Image Pro Plus Software (Media Cybernetics Inc.) and consisted of 3 to 6 images at adjacent axial locations to create one final composite. A minimum of 10 images were taken spanning the entire ear for accurate statistical analysis. Images of the control samples were obtained in the same fashion. The epidermal layer was imaged at a 20× magnification with the extended depth of field tool using the same criteria as for the dermis.

Cell Density Calculations

The densities of positively labeled MHC II cells of the dermis were calculated using Image Pro and the “masking” application, by which a “mask” was generated using area and threshold filters. The area filter was created based on prior characterization of iDC diameter, which is approximately 10–22 µm. Using those diameters, an area filter ranging from 100 µm2 to 480 µm2 was used to select for positively labeled events. The threshold filter was generated by first measuring the resultant intensity ranges due to auto-fluorescence from the cutaneous ear microenvironment. Next, intensity ranges were measured from non-specific antibody labeling. Finally, those values were used as a baseline to distinguish positively labeled events from any background / nonspecifically labeled events. Densities were then calculated in cells/mm2. For epidermal analysis, a 50 µm2 to 625 µm2 area filter was used to quantify LC. To measure changes in LC morphology, such as cellular swelling and dendrite extension, the ‘feret diameter’ filter was applied to the same images used to calculate cell density (Image Pro Plus). Data acquired from the feret diameter filter measurements for each image were pooled to generate a frequency distribution across the specified bin size ranges for each mouse and then values from each mouse were pooled and expressed as frequency per bin size range +/− SEM.

Immunohistochemistry

Ear tissue was isolated and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 24 hours at room temperature. Samples were then put in 70% ethanol at 4°C before paraffin embedding. Paraffin embedded ear sections were cut 4 µm thick and de-paraffinized for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) using the ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore) as per manufacturer’s directions, and for hematoxylin & eosin staining.

Flow cytometric analysis

Auricular draining lymph nodes (ADLN) and spleen were isolated and digested with 2 mg/ml collagenase for 20 minutes at 37°C with rotation (Sigma). Following collagenase digestion, single cell suspensions were prepared by gently pressing the tissues over a 40 µm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences) and then washed, pelleted, and re-suspended with PBA. Samples were then pre-treated with Fc Block for 10 minutes at 4°C followed by gentle rocking at 4°C for 45 minutes with an antibody cocktail including anti-CD45, anti-MHC II, and anti-CD11c. Propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) was used for live-dead discrimination. Compensation, using single color anti-CD45 splenocytes, and sample acquisition was performed using the FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences). FlowJo analytical software (Tree Star) was used to analyze the data.

mRNA isolation and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse ears using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s protocol and quantified by a spectrophotometer. First strand cDNA was synthesized using equal amounts of input RNA, the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio Rad) and the PTC-100 Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research, Inc.). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on 5µl of cDNA using forward and reverse primers designed to span introns and SYBR Green (Bio Rad) master mix for a total volume of 25 µl. A list of the forward and reverse primers (5’-3’) is as follows: GAPDH; forward CATTGCTCTCAATGACAACT, reverse GGGTTTCTTACTCCTTGGAG; CCR7: forward GGTGGCTCTCCTTGTCATTT, reverse ACATCCTTCTTGAAGCACAC; CCL21: forward CTATAGGAAGCAAGAACCAAGT, reverse TTCCTCAGGGTTTGCACATA. Samples were run on the iCycler (Bio Rad) and data normalized using GAPDH as a reference value. Data is presented as fold increase over un-irradiated controls. Statistical analysis of RT-PCR gene expression data was performed using previously described methods (18) and one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test.

Contact hypersensitivity

Contact hypersensitivity was induced in mice as previously described (19). In brief, mice were sensitized on the back with 30 µl of 0.5% 2,4-dinitro-1-fluorobenzene (DNFB) in a mixture of acetone and olive oil (4:1). Four days later, mice were exposed to radiation and after another 4 days, challenged with 10 µl of 0.2% DNFB applied to both the dorsal and ventral sides of the ear. Ear thickness was measured 24 and 48 hours following challenge using a spring loaded caliper (Mitutoyo) and data are expressed as: change in ear thickness = ear thickness – baseline thickness.

Results

TBI results in the partial depletion of both iDC and LC in a time-dependent manner

Data from our previous studies investigating the response of both mouse iDC and LC (collectively cDC) to local, ionizing radiation (IR) exposure suggests that these cells were depleted from the skin in a dose and time dependent fashion (15). Therefore, to examine if cDC were depleted in a manner similar to local IR exposure, we total body-irradiated mice with a sub-lethal dose of 6 Gy and quantified both the iDC and LC densities over time using whole-mount fluorescence microscopy as described in the materials and methods. In contrast to dermal macrophages, which are F4/80+, CD11b+, CD11c−/+, and MHC IIlo, iDC were CD11c+ and MHC IIhi as we (15) and others (6) have previously shown. Dermal (Fig. 1A) and epidermal (Fig. 1B) ear tissues from un-irradiated, control mice show densely populated anti-MHC II labeled iDC and anti-Langerin labeled LC, respectively. However, seven days following TBI exposure, both iDC (Fig. 1C) and LC (Fig. 1D) were depleted resulting in areas of tissue lacking labeled cells. In addition, the LC exhibited unique morphological changes including cellular swelling and dendrite extension following TBI (Fig. 1D) and this increase in size was quantified by image analysis and determined to be significant relative to un-irradiated controls (Supplemental Figure 1A). Similar to local IR exposure, both iDC (Fig. 1E) and LC (Fig. 1F) were depleted over time following TBI. With respect to the iDC population, the loss of cells was rapid, reaching the lowest point four days after TBI exposure; whereas the LC population had slower reduction rates, gradually reaching the lowest point around day 14 post TBI. Interestingly, while the iDC population appeared to fully repopulate the dermis by day 60 post TBI, the LC compartment was only partially repopulated.

To further examine the TBI-induced partial depletion of cDC and explore whether this was a systemic response to IR, we modified our local IR protocol. For this experiment, mice were anesthetized and placed into specially constructed jigs so that the entire body was exposed to TBI while the right ear was pulled out of the jig and shielded from IR (termed TBI − ear). We hypothesized that if the TBI-induced partial depletion was a systemic response then there would be a loss of cDC in both the ear exposed to radiation (TBI + ear) and the contralateral ear that was shielded (TBI − ear). However, seven days following a TBI − ear exposure, both the iDC (Fig. 1G) and LC (Fig 1 H) density from the TBI − ear samples remained unchanged from that of the un-irradiated controls. Importantly, the ear exposed to radiation (TBI + ear) exhibited a partial depletion of cDC; approximately 30% for iDC and 40% for LC, which was comparable to that observed on day 7 post full TBI exposure. Taken together these data suggest that like local IR exposure, TBI causes a partial depletion of cDC which is not a systemic response and only occurs when tissue/cells are directly exposed to IR.

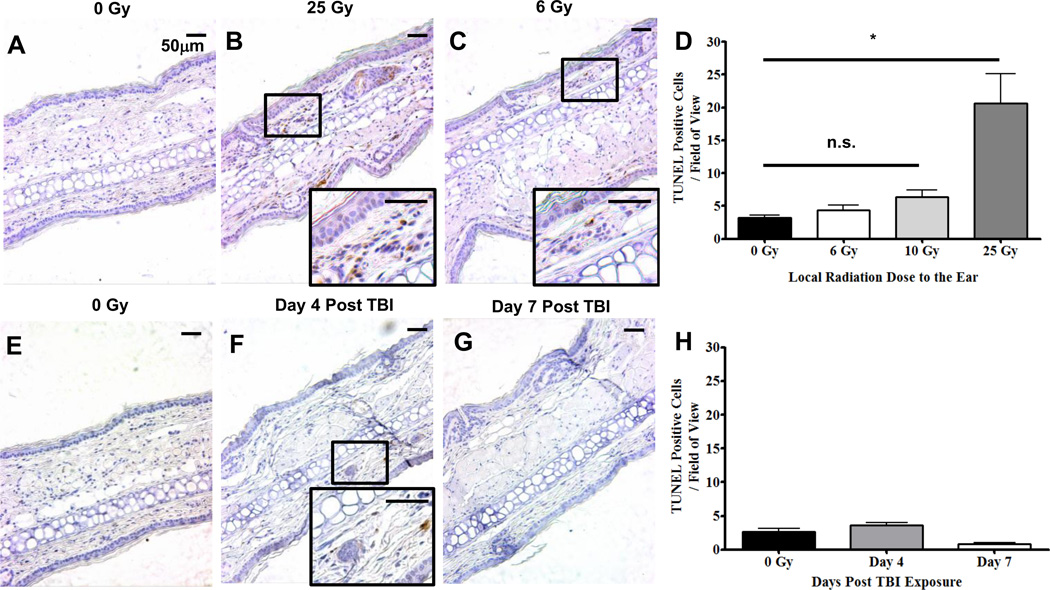

Partial depletion of cDC following TBI is not mediated by DNA fragmentation-induced apoptosis

To address the mechanism of the TBI-induced partial depletion of cDC, we first examined the possibility that it was a result of cell death. For these experiments, paraffin embedded ear sections from mice exposed/unexposed to IR were labeled with TUNEL to assess the degree of DNA fragmentation and cell death. As a positive control, mouse ears were locally exposed to 0 Gy (Fig. 2A) and 25 Gy (Fig. 2B) since our earlier studies confirmed this dose caused the most significant reduction of cDC from the ear. Six hours following the local, 25 Gy exposure, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of TUNEL positive cells relative to the un-irradiated contralateral control ear. TUNEL labeling was also examined six hours after a local dose of 6 Gy which was a comparable dose to TBI (Fig. 2C). Unlike the local 25 Gy exposure, 6 Gy did not cause a statistically significant increase in the number of TUNEL positive cells compared to the un-irradiated, contralateral control ear (Fig. 2D). Therefore, our data suggest that only high doses of IR (25 Gy) is capable of causing significant cell death in the ear at the six hour time point.

FIGURE 2. Partial depletion of cDC following TBI is not due to a DNA fragmentation-induced cell death.

A–D, Mice were either un-irradiated (A) or locally irradiated on the ear with 25 Gy (B), or 6 Gy (C) and six hours later, were sacrificed and ears prepared for TUNEL labeling. Inserts show TUNEL+ cells under higher magnification which were quantified and displayed as TUNEL Positive Cells / Field of View in D. E-H, Mice were either un-irradiated (E) or TBI and on Day 4 (F) and 7 (G) post TBI exposure, sacrificed for TUNEL labeling and quantification (H). All images were labeled using the TUNEL ApopTag Plus Peroxidase Kit and stained with haematoxylin. Data are representative of at least 10 fields of view from three mouse ear sections +/− SEM and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. * = p < 0.001. Scale bar is 50 µm.

We next wanted to assess the degree of cell death in ear skin caused by TBI. For these experiments, we investigated TUNEL labeling on days 4 and 7 post TBI as these were the most active time points of cDC loss (Fig. 1). However, relative to the un-irradiated mice (Fig. 2E), there was not a statistically significant increase in TUNEL labeling on day 4 (Fig. 2F) or 7 (Fig. 2G) post TBI (Fig. 2H). Together, these data suggest that IR-induced apoptosis is not the primary mechanism responsible for the observed cDC reduction following TBI exposure.

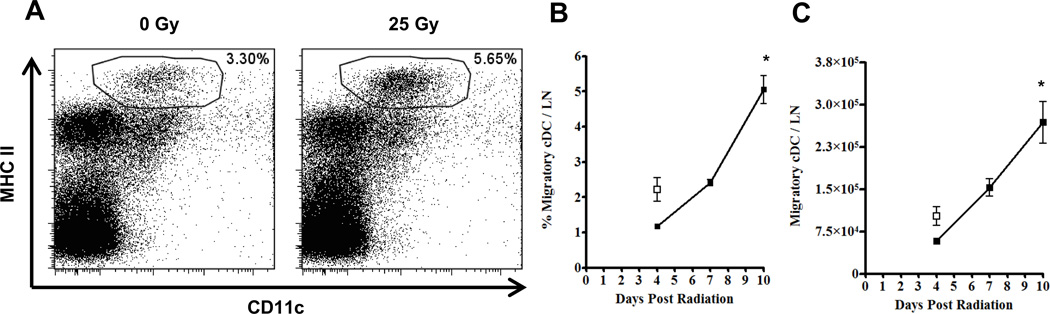

Migratory cDC from the ear can be detected in the draining lymph node following local radiation exposure

Our data suggest that apoptosis was not the primary mechanism responsible for the IR-induced cDC reduction; therefore we next hypothesized that perhaps the cells were actively migrating to the draining lymph nodes. Therefore, to address whether cDC actively migrate from the ear following IR exposure, we locally irradiated mouse ears with 25 Gy, leaving the contralateral ear un-irradiated for an internal control, and harvested the auricular draining lymph nodes (ADLN) for flow cytometric analysis. Migratory cDC, which are known to traffic to draining lymph nodes during steady state and inflammatory conditions, were identified as propidium iodide negative, CD45+, MHC IIhigh and CD11c+ as previously described (Fig. 3) (20). Local radiation of the ear, rather than TBI, was used in these experiments to directly compare the irradiated ear/ADLN to the un-irradiated contralateral control ear/ADLN. Ten days following a local dose of 25 Gy to the ear, there was a greater frequency of migratory cDC in the ADLN draining the irradiated ear relative to the un-irradiated, contralateral control (Fig. 3A). Migratory cDC in the ADLN increased in both frequency (Fig. 3B) and absolute number (Fig. 3C) over time following local IR exposure. This accumulation of migratory cDC correlated with both the TBI-induced (Fig. 1) and local IR-induced reduction of cDC from the skin as our previous studies would support. Taken together, and in accordance with the limited TUNEL labeling (Fig. 2), these data suggest that the IR-induced cDC reduction mechanism is likely due to an active migration of these cells from the ear to the ADLN.

FIGURE 3. Local exposure of mouse ears to ionizing radiation results in an increase of MHC IIhi, CD11c+ cells in the auricular draining lymph node.

A, Flow cytometric analysis of the ADLN from un-irradiated (0 Gy) and locally irradiated (25 Gy) ears of a single mouse on day 10 post IR exposure. Percentages in dot plots are those of the MHC IIhi, CD11c+ migratory cDC pre-gated on propidium iodine negative, CD45+ cells. The kinetics of both migratory cDC frequency and total cell count over time following radiation exposure are shown in B and C, respectively. White squares represent control data from the auricular lymph nodes of the un-irradiated ears. n = 6 mice per time point +/− SD, and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett's post hoc test. * = p < 0.01

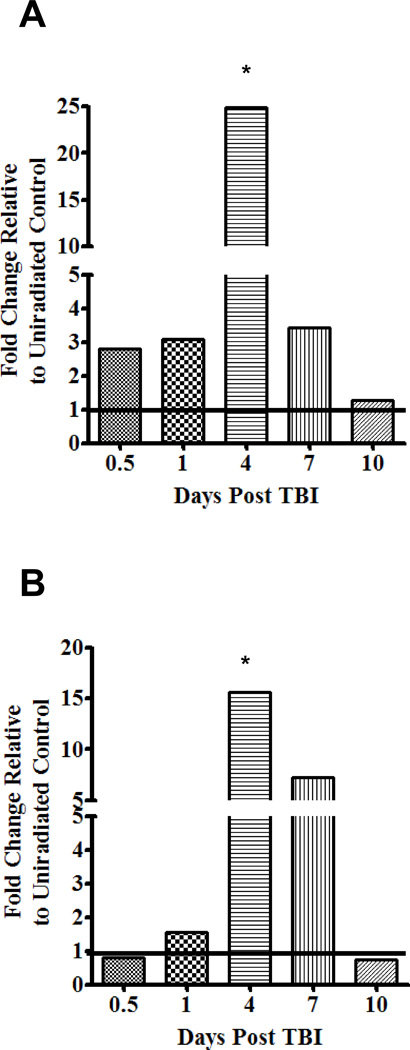

TBI causes an up-regulation of the migratory receptor CCR7 and the corresponding chemotactic ligand CCL21

To more closely examine the mechanism of the TBI-induced migration of cDC, we next focused on the migratory receptor, CCR7, and the cognate ligand, CCL21. Changes in mRNA expression of CCR7 and CCL21 as a result of TBI were examined by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4). As early as 12 hours following TBI exposure there is an up-regulation of CCR7 (Fig. 4A) above un-irradiated controls; by 24 hours CCL21 (Fig. 4B) was also up-regulated. However, by day 4 post TBI, the expression of CCR7 and CCL21 were both dramatically increased by nearly 25 and 15 fold over un-irradiated controls, respectively, and remained elevated to day 7 post TBI before returning to baseline on day 10. Importantly, these temporal genetic patterns correlate with both; 1) the mobilization of each cDC population from the skin (Fig. 1) and 2) the accumulation of cDC in the ADLN (Fig. 3B) as day 4 – 7 post TBI appear to be the most active periods of cDC migration.

FIGURE 4. TBI causes an up-regulation of the migratory receptor, CCR7, as well as the corresponding chemotactic ligand, CCL21.

Mice were exposed to TBI and a kinetic analysis was performed on the ear to examine the expression of CCR7 (A) and CCL21 (B) mRNA isolated from the cutaneous microenvironment and quantified using qRT-PCR. All values are relative to un-irradiated controls which are represented by a black line at 1. n = 3 mice per time point and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test. p value (p < 0.05) represents the increased significance of the day 4 time point relative to the other time points.

TBI causes an up-regulation of the CCL21 protein in LVYE-1 lymphatic vessels

We next examined whether TBI induced the up-regulation of CCL21 protein using whole-mount fluorescence microscopy. For these studies, we investigated day 5 post TBI since we had previously identified an increase in CCL21 mRNA on day 4 following TBI (Fig. 4B). In un-irradiated mice, punctate CCL21 labeling (Fig. 5A) was observed in LYVE-1 positive lymphatic vessels (Fig. 5B) from the mouse ear (overlaid in Fig. 5C). However, on day 5 following TBI exposure, the CCL21 labeling pattern changed and was much larger, brighter (Fig 5D), and covered a greater area of LYVE-1 lymphatic vessels (Fig. 5E) relative to un-irradiated control mice (overlaid in Fig. 5F). The changes in CCL21 labeling were then quantified and expressed as the percentage of LYVE-1 vessels that were CCL21 positive (Fig. 5G). Relative to the un-irradiated mice, there was a statistically significant 7.5 fold increase in CCL21 expression on lymphatic vessels from the day 5 post TBI mice. This increase in CCL21 protein on day 5 following TBI correlates with both the increase in CCL21 mRNA (Fig. 4B) and the rapid mobilization of cDC from the ear (Fig. 1). Taken together, these data suggest that CCL21 is up-regulated on lymphatic endothelial cells following TBI exposure indicative of a pro-migratory microenvironment for cDC.

CCR7 is required for the TBI-induced migration of cDC

To determine if CCR7 was required for the TBI-induced migration of cDC from the skin, we used CCR7−/− knockout mice. Since CCR7−/− cDC are unable to migrate from the skin (12), we hypothesized that these cells would remain in the ear skin and not be depleted following TBI. To test this, CCR7−/− mice were TBI and seven days later, sacrificed, and ears prepared for whole-mount microscopy as before. Compared to un-irradiated dermal (Fig. 6A) and epidermal (Fig. 6B) controls, the densities of iDC and LC on day seven post TBI exposure (Fig. 6C and 6D, respectively) were not significantly changed. Unlike TBI of wild type mice (Fig. 1), there were no areas within the dermis or epidermis that were devoid of cDC in the CCR7−/− mice following TBI. In addition, the cellular swelling and extension of dendrites that was observed in the LC population following TBI of wild type mice (Fig. 1D) were not observed in LC from TBI CCR7−/− mice (Fig. 6D) as these cells were not significantly changed in size relative to un-irradiated controls (Supplemental Figure 1B). Taken together, these data suggest that CCR7 is required for the migration of cDC following TBI exposure.

Mobilization of cDC from the skin following TBI impairs the CHS response to hapten

Finally, to determine if there was a functional impairment of cDC to process and present antigen, we employed a model of contact hypersensitivity (CHS). To determine the role of cDC after TBI exposure, mice were sensitized on the back at day 0, exposed to TBI or TBI − ear on day 4, and then challenged on the ear at day 8 (Fig. 7A). Relative to the DNFB sensitized, un-irradiated, vehicle challenged ears (Fig. 7B), extensive swelling and cellular infiltrate was seen 48 hours after DNFB challenge in the positive control ear (Fig. 7C). However, following TBI treatment, both the vehicle challenged ear (Fig. 7D) and the DNFB challenged ear (Fig. 7E) did not swell or display cellular infiltrates. These data would suggest that TBI and perhaps the subsequent reduction of cDC during the time of challenge greatly impairs the CHS response to hapten.

To further confirm the requirement for cDC during the challenge phase and rule out the possibility that TBI was eliminating the anti-hapten specific effector cell pool, we used the TBI − ear treatment. For these studies, mice were sensitized, exposed to the TBI − ear treatment, and then challenged with DNFB on both ears. We hypothesized that; 1) the un-irradiated ear would swell because cDC are not depleted following TBI − ear treatment, and 2) the ear exposed to radiation (TBI + ear) would have minimal swelling due to the loss of cDC. As expected, unexposed ears had comparable swelling to positive controls which persisted for two days (Fig. 7 G) whereas ears exposed to IR did not swell (Fig. 7F and 7G). Taken together, these data suggest that, due to the TBI-induced mobilization of cDC from the skin, the CHS response to hapten is greatly impaired despite that fact that anti-hapten specific effector cells are present to mount an inflammatory ear swelling response.

Discussion

We have previously shown that local IR exposure to the mouse ear results in the partial depletion of cDC (15). Here, we report a similar observation using a sub-lethal TBI dose of 6 Gy and identify the mechanism responsible for the IR-induced mobilization of cDC. Our TBI studies confirm that like local IR exposure, there is an initial mobilization of cDC (days 0–14) followed by a gradual repopulation over time (days 14–60) that we could monitor using whole-mount fluorescence microscopy. During the mobilization phase, the iDC appeared to be the first to respond to the TBI-induced trauma signals followed by the slower trafficking LC. The loss of both iDC and LC left noticeable vacancies within the dermis and epidermis, respectfully, that became larger and more prevalent over time. Interestingly, we observed unique morphological changes in the LC population following TBI, including cellular swelling and dendrite outgrowth which are a suggestive phenotype for migratory LC. In support of these findings, the same morphological characteristics have also been observed in several well established methods to trigger cDC migration such as tape stripping of the ear (17), injection of TNFα (21) or topical application of DNFB (22). Importantly, cDC were not depleted from the shielded ears of mice exposed to TBI (TBI − ear) nor were the aforementioned morphological changes in the LC population observed in those shielded ears suggesting a local mechanism for the TBI-induced partial depletion of cDC.

In our models of IR exposure, the lack of TUNEL labeling during both fast and late apoptosis would suggest that there is limited DNA fragmentation-induced cell death of both cDC and other cell types (23). Therefore, our data would support an alternative cDC reduction mechanism that is likely centered on the induction of migration which has been well characterized during steady-state and inflammatory conditions (9). However, to our knowledge, we are the first to describe an active migratory response of cDC following TBI. Our kinetics studies quantifying the accumulation of migratory cDC in the ADLN draining locally irradiated ears correlate with previous observations made by Kissenpfennig et al. (17). In these studies, TRITC was applied to the ears of EGFP-Langerin mice to track cDC migration to the ADLN and it was shown that iDC were the first to arrive in the ADLN followed by the LC (17). Using a similar protocol (17), we also identified the migratory cDC population within the ADLN (Supplemental Figure 2A) by painting the mouse ears with TRITC (Supplemental Figure 2B). On day 4 post painting, the only TRITC positive cells were those that were in the cDC migratory gate (Supplemental Figure 2C) whereas B, T and resident DC (collectively ‘remaining ADLN cells’) were TRITC negative (Supplemental Figure 2D). More importantly, when both mouse ears were painted with TRITC but only one ear was irradiated (6 Gy) while the contralateral ear remained un-irradiated, we observed an increase in the frequency (Supplemental Figure 2E) and total number of TRITC+ migratory cDC (Supplemental Figure 2F) in the ADLN from the irradiated ear relative to the ADLN from the un-irradiated control ears on day 4 post irradiation. Based on these findings and our model of TBI, we can draw parallels linking the reduction kinetics of cDC from the ear with the subsequent accumulation of cDC in the ADLN following IR exposure. iDC, with a density of approximately 110 cell / mm2 in the dermis (Fig. 1G) were rapidly depleted from the ear between days 1–4 following both local (15) and TBI exposure; however it was not until day 4 that we observed a reduction of LC that have a density of approximately 720 cells / mm2 in the epidermis (Fig. 1H). Interestingly, it was not until after day 4 following a local 25 Gy IR exposure that an increase in both frequency and absolute number of migratory cDC were observed. These increases are likely contributed by the influx of slower trafficking LC rather than iDC since these cells reached maximal reduction on day 4 post IR exposure. Importantly, we did not detect an increase in frequency or absolute number of migratory cDC in the ADLN from the un-irradiated contralateral control ear which confirms our conclusions that cDC are only depleted in skin sites exposed to IR. Not surprisingly, we also saw increases in migratory cDC frequency (Supplemental Figure 3A) and absolute number (Supplemental Figure 3B) over time following a local 6 Gy exposure that was similar to the local 25 Gy exposure used in Figure 3. This coincides with our previous studies examining a dose dependent migration of local IR exposure by which 25 Gy resulted in the greatest mobilization of cDC from the ear (15). It is possible that detection of migratory cDC following IR exposure may be dependent on the relatively short half-life of migratory cDC in the ADLN which is approximately 2–3 days (24). Although it has been suggested that migratory DC bearing certain foreign antigens can persist in draining lymph nodes for an extended duration (25) and that those antigen bearing DC may exhibit an extended half-life due to specific T cell interactions (26, 27), the antigenic profile for TBI-induced migratory cDC remains unclear.

To further investigate the migration of cDC, we explored the expression of CCR7 and CCL21 in the mouse ear following TBI as each of these proteins is required for efficient cDC chemotaxis to ADLN (12). Relative to un-irradiated controls, we observed an increase in both CCR7 and CCL21 mRNA in the ears of mice treated with TBI that was highest on day 4 and then returned to baseline 10 days post exposure. It is possible that this temporal expression pattern of CCR7 may correlate with the maturation and mobilization of each cDC subset. In this scenario, the early expression of CCR7 observed twelve hours following TBI may be due to the iDC population as these cells were the first to leave the skin which is supported by current literature (17). However, on day 4 post TBI, we observed a 25-fold increase in CCR7 expression which was likely due to receptor up-regulation on the more numerous LC population preparing to exit the epidermis as these cells require additional time to detach from neighboring keratinocytes and navigate through the cutaneous microenvironment. Importantly, as cDC (namely LC) left the skin after day 4 post TBI, the expression of CCR7 decreased until it returned to un-irradiated levels at which point migration was no longer observed. These data, and the requirement for CCR7 during the TBI-induced migration of cDC, are further supported by our studies using CCR7−/− mice as iDC and LC from these animals were not depleted from the dermis and epidermis, respectively, following IR exposure nor was an accumulation of cDC detected in the ADLN (data not shown) (12). Although it has been suggested that CCR7 is not required for the initial exit of LC from the epidermis, these studies were conducted using the application of hapten (12) and an ear tissue explant model which is significantly different from the IR-exposure model presented here. Therefore, it appears that in our model of TBI, CCR7 is required for efficient LC exit from the epidermis suggesting that IR might regulate cDC migration, and possibly maturation, in a unique way. It will be interesting to further characterize the maturation status of cDC by exploring surface phenotype and cytokine production following TBI as these traits distinguish semi-mature from fully mature DC (28). Although both semi- and fully-mature cDC express CCR7 and share similar co-stimulatory proteins, they differ in the ability to induce tolerance and immunity, respectively, in the lymph node and in situ (28). The extracellular stimuli and signaling pathways that initiate this spontaneous TBI-induced migration of cDC as well as the expression of CCR7 and maturation status of cDC, however, remain unresolved (29, 30).

CCL21 mRNA also reached maximal expression on day 4 post TBI and had a similar temporal pattern as the CCR7 profile. Recently, Jackson et al. demonstrated that CCL21 was stored within intracellular compartments (‘stores’) of human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells and expression could be increased following TNFα treatment (11). In addition Shakhar et al. also identified small, punctate CCL21 labeling in steady-state mouse lymphatic vessels within the ear (31). It is possible that immediately following TBI, CCL21 protein is actively released from these ‘stores’ into the cutaneous microenvironment which further induces iDC maturation and facilitates mobilization. The subsequent emptying of these ‘stores’ might then trigger the production of CCL21 mRNA which was seen as early as day 1 and was most significantly increased on day 4 post TBI relative to un-irradiated controls. Indeed, as our intracellular staining would suggest, it would appear that on day 5 post TBI, fluorescent labeling for CCL21 protein within LYVE-1+ vessels was brighter and covered a larger area relative to un-irradiated controls. These data are in agreement with previous findings suggesting that immobilized CCL21 on mouse lymphatic vessels has an equally important role as soluble CCL21 and is essential for cDC docking and entry into draining lymphatics (31). Unexpectedly, we also observed an up-regulation of LYVE-1 on some portions of lymphatic vessels from mice exposed to TBI. We are currently investigating these findings as little is known of the IR-induced effects on lymphatic endothelial cells. Recently it was shown by using LYVE-1−/− mice, that LYVE-1 was dispensable for cDC migration (32) while others have suggested that cDC enter lymphatic vessels at sites of discontinuous LVYE-1 expression (33). Importantly, although the up-regulation of CCL21 was observed on all TBI lymphatics, LYVE-1 up-regulation was heterogeneous on these vessels.

Interestingly, the mRNA expression of both CCR7 and CCL21 was dramatically up-regulated on day 4 post TBI relative to un-irradiated controls and the additional time points examined. Although it is possible that TBI might act as a classic pro-inflammatory stimulus by inducing granulocyte extravasation into irradiated tissues and subsequent up-regulation of CCR7 and CCL21 mRNA, this seems unlikely because: 1) white blood cell counts (Supplemental Figure 4A), including Ly-6G+ granulocytes (Supplemental Figure 4B), from TBI exposed mice were significantly reduced in peripheral blood samples collected between days 1 to 21 post IR exposure and 2) we did not observe an increase in Ly-6G+ granulocytes (Supplemental Figure 4C) within the ear tissue from locally irradiated (Supplemental Figure 4D) or TBI exposed mice (Supplemental Figure 4E) as these cells remained co-localized with the CD31+ vasculature. We are currently examining the early role of inflammatory cytokines including TNFα and IL-1β since these are also produced by non-immune cells, as well as the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, which has been shown to augment CCL21 production (34). However, it is also possible that these findings could be explained by the activation of NF-κB via an inflammatory cytokine-independent mechanism. Previous studies in the field have demonstrated that IR alone can activate NF-κB via direct double strand DNA damage or indirect DNA damage by the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (35). In this pathway, IR-induced DNA damage up-regulates ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and following it’s translocation to the cytoplasm, activates the inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) which liberates NF-κB from the inhibitor κBα (IκBα) complex. Therefore, it is possible in our model of TBI that as DNA damage and/or ROS accumulate over time, NF-κB is activated which causes the release and production of CCL21 protein and mRNA, respectively, from lymphatic endothelial cells as well as induces the up-regulation of CCR7 mRNA in cDC.

The partial depletion of cDC after local and TBI could have a significant impact on the successful maintenance of immune surveillance within the cutaneous microenvironment for individuals exposed to IR. Regarding cDC function, contact hypersensitivity (CHS) to epicutaneously applied hapten has been one of the gold standards to examine the role of cDC in the elicitation of an adaptive immune response (36). Initial experiments using conditional and inducible mouse models to selectively deplete LC and iDC before sensitization suggested that iDC were essential for the T cell-mediated ear swelling response while LC were thought to have a toleragenic role by limiting ear swelling (37). However, this functional dichotomy between iDC and LC has been recently challenged suggesting that these cells share roles during CHS. In addition, the magnitude of ear swelling was largely determined by the amount of hapten and the number of cDC that activate the anti-hapten effector T cells (38, 39). Therefore, rather than examining the role of cDC before sensitization (37) we asked if there was a functional impairment of cDC during the challenge phase following TBI. In our model of CHS, the impetus was to examine the functional response of cDC after IR exposure as this would aid in the development of future treatment protocols for patients undergoing radiation therapy or victims of accidental/deliberate radiological disasters. Contrary to other CHS models (37), both the iDC and LC populations remained intact during the sensitization phase of our CHS experiments, which enabled us to examine the functional relevance of cDC during the challenge phase. Our data would suggest that there may be a correlation between the TBI-induced mobilization of cDC upon challenge and subsequent impairment of CHS to epicutaneously applied hapten. Although we observed a reduction in circulating T cell numbers in the blood and ADLN following TBI (data not shown), our TBI − ear studies would suggest that there are a sufficient number of T cells to elicit an ear swelling response as long as cDC are present in the skin upon challenge. As an additional control to demonstrate reduced ear swelling on irradiated skin, we locally exposed one ear with a dose of 6 Gy while the contralateral ear remained un-exposed. Following DNFB challenge to both ears, we observed reduced swelling on the irradiated ear and normal swelling on the un-irradiated ear (data not shown). Taken together, these data confirm the requirement for un-irradiated cDC and/or an un-irradiated cutaneous microenvironment during the challenge phase of CHS to elicit a normal swelling response and may further suggest that the number of cDC upon challenge could dictate the swelling response (38–40).

We are currently investigating the cytokine milieu within the cutaneous microenvironment following TBI as the balance between type 1 and type 2 cytokines may further advance our understanding of the TBI-induced migration of cDC as well as the induction of both CCR7 and CCL21. Depending on how this TBI-induced cytokine microenvironment is skewed, it could greatly impact the conditioning of cDC within the skin and dictate how these cells interact with T cells in draining lymph nodes (10). Recently, it has been suggested that atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic inflammatory skin disease, is, in part, initiated and driven by cDC (41) and patients who suffer from AD often exhibit a type 2 cytokine profile within the skin. However, despite an increased understanding in the immunopathology, AD still remains an idiopathic disease that manifests in individuals with a predetermined genetic background or in those exposed to a variety of environmental stimuli (42). Interestingly, patients undergoing radiotherapy often develop radiation-induced dermatitis (radio-dermatitis) and express many of the same clinical signs and symptoms as those observed with AD. It is possible that the IR-induced migration of cDC coupled with a newly generated cytokine microenvironment might elicit an adaptive response that manifests into radio-dermatitis. However further investigation into the function and phenotype of these IR-induced migratory cDC is required before we can make these conclusions.

In summary, we have identified a CCR7-dependent mechanism that is responsible for the TBI-induced migration of cDC. The up-regulation of CCL21 following TBI would also suggest that migration is directing these cells towards the lymphatics and ultimately the ADLN. As a result of the cDC mobilization from the skin, we believe the host is more susceptible to pathogen entry as the impaired CHS response would suggest. Indeed, iDC are required for efficient cross presentation of HSV-1 antigens to naïve CD8 T cells (43) and the surveillance of both iDC and LC are needed to dictate distinct humoral responses to epicutaneously applied antigens (44). Importantly, in our model of sub-lethal TBI, cDC are not completely depleted from the skin as a fraction of both iDC and LC persist following IR exposure. Therefore, it is possible that the maturation status of cDC and/or newly generated cytokine milieu following TBI may dictate altered skin homeostasis and immune surveillance over time after IR exposure. We are currently investigating how a reduction of cDC impacts immune regulation in the skin following TBI as these studies will aid in the development of mitigating agents that may alleviate radio-dermatitis and onset of cutaneous radiation syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the University of Rochester CMCR for many helpful discussions, Abigail L. Sedlacek (University of Rochester, Department of Microbiology and Immunology) for help with the contact hypersensitivity experiments, and Barbara Stroyer (University of Rochester, Department of Radiation Oncology) for assistance with the immuno-histochemistry. In addition we would like to thank Dr. Bruce Fenton, Director of the CMCR Imaging Core (University of Rochester, Department of Radiation Oncology) for his expertise with immunofluorescence image analyses and CMCR biostatistician Dr. Tanzy Love (University of Rochester, Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology) for her guidance on the statistical analyses.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- cDC

cutaneous dendritic cell

- iDC

interstitial dendritic cell

- LC

Langerhans cell

- IR

ionizing radiation

- TBI

total body irradiation

- TBI + ear and TBI − ear

total body irradiation of mice and ears exposed to radiation and the shielded contralateral ear respectively

- Gy

Gray

- ADLN

auricular draining lymph node

- CHS

contact hypersensitivity

- DNFB

2, 4-dinitro-1-fluorobenzene.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the University of Rochester Center for Medical Countermeasures against Radiation (CMCR), an NIH/NIAID Center of Excellence number U19-AI091036.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Norman Coleman C, Lurie N. Emergency medical preparedness for radiological/nuclear incidents in the United States. J Radiol Prot. 2012;32:N27–N32. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/32/1/N27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstock DM, Case C, Jr, Bader JL, Chao NJ, Coleman CN, Hatchett RJ, Weisdorf DJ, Confer DL. Radiologic and nuclear events: contingency planning for hematologists/oncologists. Blood. 2008;111:5440–5445. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peter RU. Cutaneous radiation syndrome in multi-organ failure. BJR Suppl. 2005;27:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorr H, Meineke V. Acute radiation syndrome caused by accidental radiation exposure - therapeutic principles. BMC Med. 2011;9:126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helft J, Ginhoux F, Bogunovic M, Merad M. Origin and functional heterogeneity of non-lymphoid tissue dendritic cells in mice. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:55–75. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Wagers A, Loubeau M, Isola LM, Lubrano L, Najfeld V, Phelps RG, Grosskreutz C, Scigliano E, Frenette PS, Merad M. Identification of a radio-resistant and cycling dermal dendritic cell population in mice and men. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2627–2638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Moore K, Kleijmeer M, Liu Y, Duvert-Frances V, Vincent C, Schmitt D, Davoust J, Caux C, Lebecque S, Saeland S. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, Wagers A, Peters W, Charo I, Weissman IL, Cyster JG, Engleman EG. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez D, Vollmann EH, von Andrian UH. Mechanisms and consequences of dendritic cell migration. Immunity. 2008;29:325–342. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffre O, Nolte MA, Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson LA, Jackson DG. Inflammation-induced secretion of CCL21 in lymphatic endothelium is a key regulator of integrin-mediated dendritic cell transmigration. Int Immunol. 2010;22:839–849. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano H, Gunn MD. Gene duplications at the chemokine locus on mouse chromosome 4: multiple strain-specific haplotypes and the deletion of secondary lymphoid-organ chemokine and EBI-1 ligand chemokine genes in the plt mutation. J Immunol. 2001;166:361–369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norval M, McLoone P, Lesiak A, Narbutt J. The effect of chronic ultraviolet radiation on the human immune system. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings RJ, Mitra S, Foster TH, Lord EM. Migration of skin dendritic cells in response to ionizing radiation exposure. Radiat Res. 2009;171:687–697. doi: 10.1667/RR1600.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen JG, Emerson DM, Landy JJ, Head LR, Basinger CE. The causes of death from total body irradiation; an analysis of the present status after fifteen years of study. Ann Surg. 1957;146:322–341. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195709000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kissenpfennig A, Henri S, Dubois B, Laplace-Builhe C, Perrin P, Romani N, Tripp CH, Douillard P, Leserman L, Kaiserlian D, Saeland S, Davoust J, Malissen B. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity. 2005;22:643–654. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobr A, Olvera-Gomez I, Igyarto BZ, Haley KM, Hogquist KA, Kaplan DH. Acute ablation of Langerhans cells enhances skin immune responses. J Immunol. 2010;185:4724–4728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginhoux F, Collin MP, Bogunovic M, Abel M, Leboeuf M, Helft J, Ochando J, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Grisotto M, Snoeck H, Randolph G, Merad M. Blood-derived dermal langerin+ dendritic cells survey the skin in the steady state. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3133–3146. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishibu A, Ward BR, Jester JV, Ploegh HL, Boes M, Takashima A. Behavioral responses of epidermal Langerhans cells in situ to local pathological stimuli. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:787–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishibu A, Ward BR, Boes M, Takashima A. Roles for IL-1 and TNFalpha in dynamic behavioral responses of Langerhans cells to topical hapten application. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;45:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonathan EC, Bernhard EJ, McKenna WG. How does radiation kill cells? Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamath AT, Henri S, Battye F, Tough DF, Shortman K. Developmental kinetics and lifespan of dendritic cells in mouse lymphoid organs. Blood. 2002;100:1734–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg S, Oran A, Wajchman J, Sasaki S, Maris CH, Kapp JA, Jacob J. Genetic tagging shows increased frequency and longevity of antigen-presenting, skin-derived dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:907–912. doi: 10.1038/ni962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henrickson SE, Mempel TR, Mazo IB, Liu B, Artyomov MN, Zheng H, Peixoto A, Flynn MP, Senman B, Junt T, Wong HC, Chakraborty AK, von Andrian UH. T cell sensing of antigen dose governs interactive behavior with dendritic cells and sets a threshold for T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:282–291. doi: 10.1038/ni1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josien R, Li HL, Ingulli E, Sarma S, Wong BR, Vologodskaia M, Steinman RM, Choi Y. TRANCE, a tumor necrosis factor family member, enhances the longevity and adjuvant properties of dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:495–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Angeli V. Factors and signals that govern the migration of dendritic cells via lymphatics: recent advances. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:273–287. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez-Sanchez N, Riol-Blanco L, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. The multiple personalities of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:5153–5159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tal O, Lim HY, Gurevich I, Milo I, Shipony Z, Ng LG, Angeli V, Shakhar G. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2141–2153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gale NW, Prevo R, Espinosa J, Ferguson DJ, Dominguez MG, Yancopoulos GD, Thurston G, Jackson DG. Normal lymphatic development and function in mice deficient for the lymphatic hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:595–604. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01503-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakao S, Zandi S, Faez S, Kohno R, Hafezi-Moghadam A. Discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in corneal limbal lymphatics: dual function as microvalves and immunological hot spots. FASEB J. 2012;26:808–817. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-183897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, Li ZW, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed KM, Li JJ. NF-kappa B-mediated adaptive resistance to ionizing radiation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grabbe S, Schwarz T. Immunoregulatory mechanisms involved in elicitation of allergic contact hypersensitivity. Immunol Today. 1998;19:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan DH, Kissenpfennig A, Clausen BE. Insights into Langerhans cell function from Langerhans cell ablation models. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2369–2376. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clausen BE, Kel JM. Langerhans cells: critical regulators of skin immunity? Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:351–360. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochweller K, Wabnitz GH, Samstag Y, Suffner J, Hammerling GJ, Garbi N. Dendritic cells control T cell tonic signaling required for responsiveness to foreign antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5931–5936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911877107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toews GB, Bergstresser PR, Streilein JW. Epidermal Langerhans cell density determines whether contact hypersensitivity or unresponsiveness follows skin painting with DNFB. J Immunol. 1980;124:445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bieber T, Novak N, Herrmann N, Koch S. Role of dendritic cells in atopic dermatitis: an update. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;41:254–258. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Novak N. New insights into the mechanism and management of allergic diseases: atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedoui S, Whitney PG, Waithman J, Eidsmo L, Wakim L, Caminschi I, Allan RS, Wojtasiak M, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Brooks AG, Heath WR. Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:488–495. doi: 10.1038/ni.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagao K, Ginhoux F, Leitner WW, Motegi S, Bennett CL, Clausen BE, Merad M, Udey MC. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells and langerin-expressing dermal dendritic cells are unrelated and exhibit distinct functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.