Abstract

The intervertebral discs, located between adjacent vertebrae, are required for stability of the spine and distributing mechanical load throughout the vertebral column. All cell types located in thes middle regions of the discs, called nuclei pulposi, are derived from the embryonic notochord. Recently, it was shown that the hedgehog signaling pathway plays an essential role during formation of nuclei pulposi. However, during the time that nuclei pulposi are forming, Shh is expressed in both the notochord and the nearby floor plate. To determine the source of SHH protein sufficient for formation of nuclei pulposi we removed Shh from either the floor plate or the notochord using tamoxifen-inducible Cre alleles. Removal of Shh from the floor plate resulted in phenotypically normal intervertebral discs, indicating that Shh expression in this tissue is not required for disc patterning. In addition, embryos that lacked Shh in the floor plate had normal vertebral columns, demonstrating that Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient for pattering the entire vertebral column. Removal of Shh from the notochord resulted in the absence of Shh in the floor plate, loss of intervertebral discs and vertebral structures. These data indicate that Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient for patterning of the intervertebral discs and the vertebral column.

Keywords: Notochord, Shh, Floor plate, Nucleus pulposus/nuclei pulposi, Intervertebral discs

Introduction

The intervertebral discs are located between adjacent vertebrae and are required for normal movement and function of the vertebral column. In mammals, intervertebral discs are composed of three distinct tissues. The middle part of the disc is called the nucleus pulposus and is a hydrogel-like structure made primarily of proteoglycans. The nucleus pulposus is surrounded by the annulus fibrosis, which is composed of layers of collagen I fiber bundles arranged in alternating directions and a less organized layer of collagen II fibers (Humzah and Soames, 1988; Smith et al., 2011). The outer region of each disc is attached to adjacent vertebrae by the end plates(Humzah and Soames, 1988).

Damage to or degeneration of the intervertebral discs is believed to cause most cases of back pain. In the United States up to 85% of people are affected by back pain at some point in their lives, a prevalence that corresponds to back pain-related health care costing approximately 100 billion dollars annually (Andersson, 1999; Katz, 2006; Smith et al., 2011). Current treatments for back pain only treat the symptoms of the pain and not the underlying cause. While artificial disc replacement holds some promise for aiding patients with debilitating pain, this approach is highly invasive, subject to failure through wearing and does not work for all types of disc disease (Hanley et al., 2010; Mirza and Deyo, 2007).

Previous work has demonstrated that the embryonic mouse notochord, which is present from embryonic day (E) 7.5 until E12.5, forms all cell types in the nucleus pulposus(Choi et al., 2008; Choi and Harfe, 2011). The nucleus pulposus persists throughout adult life in both mice and in humans(Dahia et al., 2009; Humzah and Soames, 1988; Walmsley, 1953). During embryogenesis, the notochord serves as a signaling center and is required for formation of the floor plate(Fan and Tessier-Lavigne, 1994; Johnson et al., 1994). The floor plate first forms at E8.5 and plays an essential role in patterning all cell types in the neural tube(Roelink et al., 1995).

The secreted signaling molecule SHH is expressed and secreted from both the notochord and floor plate prior to formation of both nuclei pulposi and the vertebral column. Previous work from a number of laboratories has shown that Shh expression in the notochord is required to induce Shh expression in the floor plate(Fan and Tessier-Lavigne, 1994; Johnson et al., 1994). In Shh null embryos, the notochord initially forms but is quickly degraded(Chiang et al., 1996). As a result of loss of the notochord, Shh is not induced in the floor plate and cell types in the neural tube are not formed correctly.

Previously, we removed the hedgehog signaling pathway from both the notochord and floor plate(Choi and Harfe, 2011). In these embryos, nuclei pulposi did not form correctly and defects in the vertebral column were observed. Temporal removal of Shh from both the notochord and floor plate demonstrated that this gene was required for formation of the notochord sheath that surrounds the notochord and formation of the vertebral column(Choi and Harfe, 2011). These experiments were not able to determine if Shh was required in the notochord, floor plate, or both locations for formation of the intervertebral discs and vertebral column.

In the current report, we removed Shh from either the notochord or floor plate to determine the source of SHH required for patterning of the vertebral column and nuclei pulposi. This was accomplished using tamoxifen-inducible Cre alleles. Removal of Shh from the notochord abolished Shh expression in the floor plate and resulted in the loss of vertebral structures and nuclei pulposi. In contrast, removal of Shh from the floor plate resulted in a phenotypically normal vertebral column and intervertebral discs. These data indicate that surprisingly, Shh expression in the floor plate is not required for patterning of either the vertebral column or intervertebral discs.

Materials and methods

Mice

Animals were handled in accordance with the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The floxed conditional Shh allele (Shhf/f), ShhcreERT2, and Foxa2creERT2 (also called Foxa2 mcm) alleles have been described previously (Dassule et al., 2000; Harfe et al., 2004; Park et al., 2008). Mice containing the Shhf/ShhcreERT2 alleles were generated by crossing Shhf/f females to ShhcreERT2/+ males. Shhf/f;Foxa2creERT2 embryos were generated by crossing Shhf/f females with Shhf/+; Foxa2creERT2 males. Tamoxifen was orally gavaged at 3mg/ 40g bodyweight in E7.5 or E9.5 pregnant dams to generate Shhf/ShhcreERT2 or Shhf/f;Foxa2creERT2 embryos,. Tamoxifen-treated embryos of the genotype Shhf/ShhcreERT2, or Foxa2creERT2 were phenotypically wild type and were used as controls. R26R reporter mice used in this study have been described previously (Soriano, 1999).

Wholemount RNA in situ hybridization, skeleton preparation, and Xgal staining

Wholemount RNA in situ hybridization, skeleton preparation and Xgal staining was performed as previously described (Harfe et al., 2004; Murtaugh et al., 1999; Wilkinson and Nieto, 1993). The floxed region of Shh (Zhu et al., 2008) was cloned and used as a probe to determine the population of cells that had undergone recombination.

Histology

For histology, embryos were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde overnight and were decalcified in Cal-EX (Fisher) overnight. Embryos were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 10μm. For alcian blue picro-sirius red staining, sections were stained with alcian blue for 15min, with picro-sirius red for 45 min and then were washed in acidified water (0.025% acetic acid).

Results and Discussion

CRE-inducible recombination can be targeted to the floor plate or notochord using the tamoxifen-inducible ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 alleles

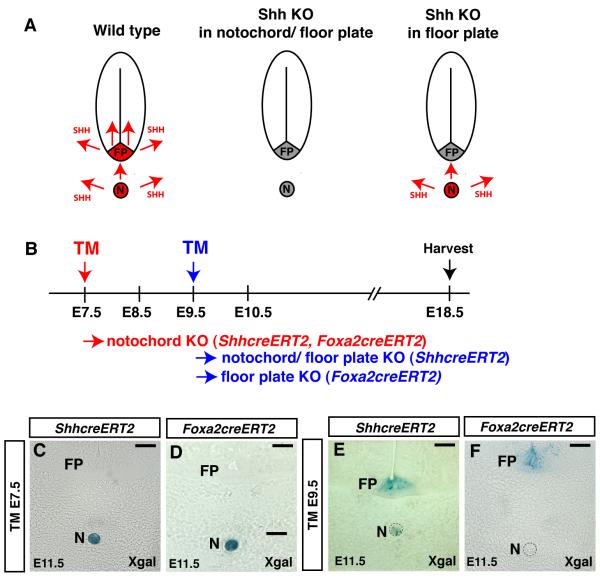

SHH protein is produced by both notochord and floor plate cells. Previously, we reported that removal of Shh (or hedgehog signaling) concurrently from both these location resulted in defects in the formation of nuclei pulposi(Choi and Harfe, 2011). These data were unable to determine the source of SHH protein required for proper formation of nuclei pulposi. To investigate the potential role SHH protein produced from the notochord or floor plate may have during intervertebral disc development, mice were generated in which Shh was removed individually from either of these locations (Fig. 1 A, B). This was accomplished using two tamoxifen-inducible Cre lines, ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2. The ShhcreERT2 allele drives expression of Cre recombinase in all cells that normally produce Shh(Choi et al., 2008; Harfe et al., 2004). In the notochord, expression is observed at E7.5 and in the floor plate at E8.5, as this structure begins to form. The Foxa2creERT2 allele drives Cre expression in the notochord at E7.5 however, unlike what is observed using the ShhcreERT2 allele, from E8.5 onward CRE expression is only observed in the floor plate(Park et al., 2008).

Figure 1. The tamoxifen-inducible alleles ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 can be used to remove gene expression in the notochord or floor plate.

(A) A schematic of Shh expression in the notochord and floor plate in wild type, in embryos in which Shh was removed from both the notochord and floor plate and in embryos in which Shh was only removed from the floor plate. (B) Strategy used to remove Shh expression from the notochord or floor plate using the tamoxifen (TM)-inducible ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles. (C-F) Temporal activation of CRE in ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 embryos that were treated with tamoxifen at E7.5 or E9.5. CRE activity was visualized using the CRE-inducible R26R reporter allele. (C, D) Treatment of E7.5 embryos containing either the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles with tamoxifen resulted in activation of the R26R allele in the notochord but not the floor plate. (E) Treatment of E9.5 embryos containing the ShhcreERT2 allele resulted in R26R activation in both the floor plate and notochord. (F) In contrast, treatment of E9.5 embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 allele with tamoxifen activated R26R reporter expression in the floor plate but not in the notochord. All images shown are from the forelimb level of embryos. Notochord (N); Floor plate (FP). Scale bar= 50μm.

To confirm that the ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 alleles can activate a CRE-inducible reporter in the floor plate or notochord depending on when tamoxifen was administered, mice containing these alleles were crossed to the CRE-inducible R26R lacZ reporter allele(Soriano, 1999). To control when CRE protein was active in a given tissue, a single dose of tamoxifen was administered to pregnant dams at E7.5 or E9.5. After administration of tamoxifen embryos were harvested at E11.5 and examined for LacZ expression using X-gal staining.

These data confirmed that a single tamoxifen treatment of E7.5 embryos containing either the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles resulted in activation of the CRE-inducible reporter allele only in the notochord and not in the floor plate (Fig. 1C and D). Tamoxifen exposure of E9.5 embryos carrying the ShhcreERT2 allele resulted in reporter activity in both the notochord and floor plate while embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 allele had reporter expression in the floor plate but not in the notochord (Fig. 1E and F). These data demonstrate that by controlling the time of tamoxifen exposure in embryos containing either the Foxa2creERT2 or ShhcreERT2 alleles, CRE-inducible recombination can selectively occur in either the notochord or floor plate.

Removal of Shh expression from either the notochord or floor plate

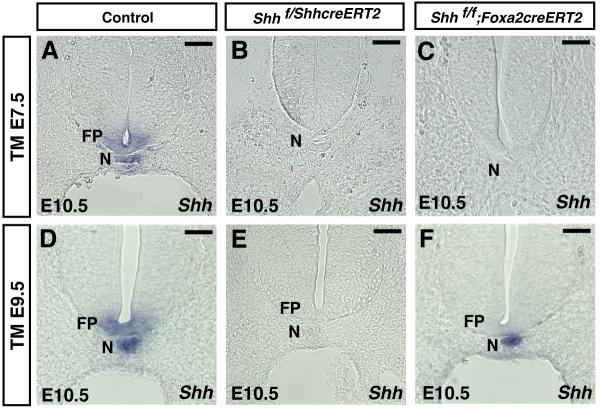

To determine the role of SHH in formation of nuclei pulposi a conditional floxed allele of Shh (Shhf/f) was crossed to the tamoxifen-inducible Cre allele(Dassule et al., 2000). To test whether Shh was efficiently removed from the notochord or floor plate in these crosses, RNA in situ hybridization was performed using a probe against the floxed region of Shh (Zhu et al., 2008).

Upon tamoxifen exposure at E7.5 in either ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 embryos, Shh was absent from both the notochord and floor plate (Fig. 2A-C). In this experiment, recombination of the Shh floxed allele only occurred in the notochord but expression was lost in both the notochord and floor plate. These data were consistent with previous reports that Shh expression is required for the formation of floor plate (Ang and Rossant, 1994; Chiang et al., 1996; Roelink et al., 1995). Administration of tamoxifen at E9.5 in embryos containing the ShhcreERT2 allele abolished Shh expression in both the notochord and floor plate (Fig. 2E). Tamoxifen treatment of embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 allele at E9.5 lacked Shh expression in the floor plate but retained expression in the notochord (Fig. 2F). Control embryos were treated with tamoxifen but did not contain a Cre allele. These data demonstrated that by controlling the developmental stage that embryos were exposed to tamoxifen in the ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 genetic backgrounds, Shh could be removed from either the notochord/floor plate or only the floor plate.

Figure 2. Removal of Shh from the notochord/floor plate or only from the floor plate using the ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 alleles.

Section RNA in situ hybridizations using a probe specific for the floxed region of Shh in control and tamoxifen-treated mutant embryos. Control and mutant embryos were harvested at E10.5 after a single dose of tamoxifen was administered at E7.5 (A-C) or E9.5 (D-F). Shh transcripts were not detected in the notochord or floor plate of mutant embryos containing either the ShhcreERT2 (B) or Foxa2creERT2 (C) alleles after exposure to tamoxifen at E7.5. In these embryos CRE was only active in the notochord. Shh expression in the notochord is required for formation of the floor plate, which is why no Shh transcripts were detected in the floor plate in addition to the notochord of mutant embryos (see text for details). Treatment of E9.5 embryos containing the ShhcreERT2 allele resulted in the removal of Shh from both the notochord and floor plate (E). Treatment of E9.5 embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 allele resulted in the removal of Shh from the floor plate but not notochord (F). Tamoxifen treatment of embryos at E9.5 containing the ShhcreERT2 allele resulted in CRE recombination in both the floor plate and notochord while embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 only underwent recombination in the floor plate (see also Fig. 1). All images shown are from the hindlimb level of embryos. Scale bar = 50μm.

Shh expression in the notochord but not the floor plate is required for formation of intervertebral discs

Shh and the hedgehog signaling pathway have been shown to play essential roles in the patterning of the vertebral column and intervertebral discs(Chiang et al., 1996; Choi and Harfe, 2011). Shh null embryos form a notochord but this structure quickly degenerates resulting in loss of the floor plate, nuclei pulposi and patterning defects in the neural tube and axial skeleton (Chiang et al., 1996). Since Shh is expressed both in the notochord and floor plate, the role Shh played in these tissues during the development of the vertebral column and intervertebral discs was unknown. To determine the role(s) that Shh expression in either the notochord or floor plate plays during vertebral column patterning, Shh was individually removed from these tissues using the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles.

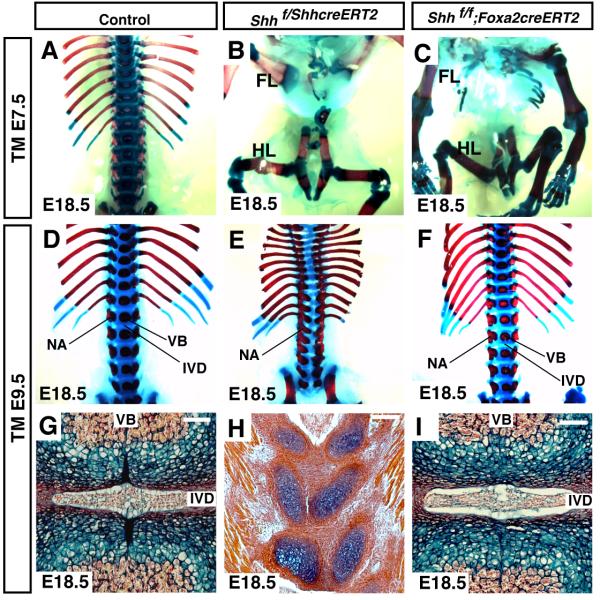

Removal of Shh from the notochord (E7.5 tamoxifen treatment) using either the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles resulted in severe axial skeleton malformation (Fig. 3A-C). In these experiments, removal of Shh from the notochord resulted in the loss of Shh expression in the floor plate (see Fig. 2) and the phenotypes produced were consistent with those of previous studies in which Shh was absent in both the notochord and floor plate (Chiang et al., 1996; Choi and Harfe, 2011). The ShhcreERT2 and Foxa2creERT2 alleles drive Cre expression in other, only partially overlapping tissues outside the notochord. The identical phenotypes produced in the vertebral column upon removal of Shh at E7.5 using these two alleles suggests that removal of Shh in locations outside the notochord/floor plate does not play a major role in skeletal or intervertebral disc patterning. In all experiments, control embryos were also treated with tamoxifen. The lack of a phenotype in these embryos indicates that tamoxifen exposure in embryos that have wild type Shh alleles does not cause a visible phenotype.

Figure 3. Shh expression in the notochord, but not the floor plate, is required for formation of intervertebral discs.

Removal of Shh from the notochord at E7.5 using either the ShhcreERT2 allele (B) or the Foxa2creERT2 allele (C) resulted in the absence of a vertebral column at E18.5 (A-C). Removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate at E9.5 using the ShhcreERT2 allele resulted in severe malformation of the vertebral column and a complete absence of a vertebral column caudal to lumbar vertebrae (D and E). Histological analysis of frontal sections of thoracic vertebral columns confirmed that the vertebral column was abnormal and that nuclei pulposi of the intervertebral discs were absent (H). Mice in which Shh was removed from the notochord and floor plate formed split vertebrae (E and H). In the mutant mice, vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs were not present and neural arches were elongated into the vertebral body. Removal of Shh from only the floor plate at E9.5 did not result in the production of visible phenotypic abnormalities in the vertebral column or intervertebral discs (F and I). Forelimb (FL); Hindlimb (HL); vertebral body (VB); neural arch (NA);, intervertebral disc (IVD). Scale bar = 100μm.

To determine if Shh expression in the floor plate played a role in the formation of the intervertebral discs, we removed Shh at E9.5 using either the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles. Embryos in which Shh was removed from the E9.5 notochord and floor plate showed severe malformation in both the axial skeleton (Fig. 3E) and intervertebral discs (Fig. 3H). In contrast, normal vertebral columns and intervertebral discs were obtained when Shh was removed only from the floor plate (Fig. 3F and I). In these embryos, Shh was still expressed in the notochord (Fig. 2). These results demonstrate that Shh expression in the floor plate is not required for the formation or patterning of the vertebral column or intervertebral disc in animals that have Shh expression in the notochord. These data suggest that Shh produced by the notochord is sufficient for the formation of both the vertebral column and nuclei pulposi.

Shh expression in the notochord, but not the floor plate, is sufficient for normal Pax1 expression

Differentiation of sclerotome requires SHH but the in vivo source of SHH necessary for the formation of this tissue remains controversial (Fan and Tessier-Lavigne, 1994; Johnson et al., 1994). Ectopic expression of Shh or implantation of tissues expressing Shh, for example the floor plate or the notochord, can induce expression of the sclerotome marker Pax1. Experiments in which Shh was removed from the entire embryo demonstrated that Shh was not essential for initiation of Pax1 expression but was required for the maintenance of Pax1 expression (Chiang et al., 1996). None of these experiments were able to determine if Shh was required in the floor plate, notochord or both these structures for patterning of the sclerotome.

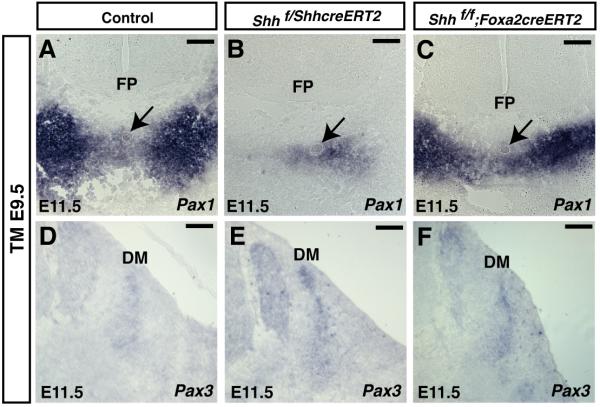

To determine if Shh expressed in the floor plate or notochord was sufficient for differentiation of paraxial mesoderm, Shh was removed from the notochord or floor plate using the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles. RNA in situ hybridization was then performed to determine expression levels of Pax1 and Pax3. Embryos in which Shh was removed from the E9.5 notochord and floor plate using the ShhcreERT2 allele displayed a decrease in expression of Pax1 in the ventral sclerotome (Fig. 4A and C) but no increase in cell death (Supplemental Figure 1). Removal of Shh from both the floor plate and notochord played no role in patterning of the dermomyotome (Fig. 4 D-F and (Choi and Harfe, 2011)). Embryos in which Shh was maintained in the E9.5 notochord but removed from the floor plate had normal levels of Pax1 expression in the ventral sclerotome (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient to maintain Pax1 expression in the ventral sclerotome.

Figure 4. Pax1 and Pax3 expression in mice lacking Shh in the notochord and/or floor plate.

(A-C) Section RNA in situ hybridization of Pax1 in E11.5 embryos at rostral level. Pax1 expression was decreased by removal of Shh in the notochord and floor plate (B) but was not altered by removal of Shh in the floor plate (C). (D-E) Section RNA in situ hybridization of Pax3 in E11.5 embryos. No difference in Pax1 expression was observed in embryos that lacked Shh in the notochord (F) or notochord and floor plate (E) compared to controls (D). All images shown are from the forelimb level of embryos. Arrows denote the notochord. FP = floor plate, DM = dermomyotome. Scale bar = 100μm.

Role of the notochord during development

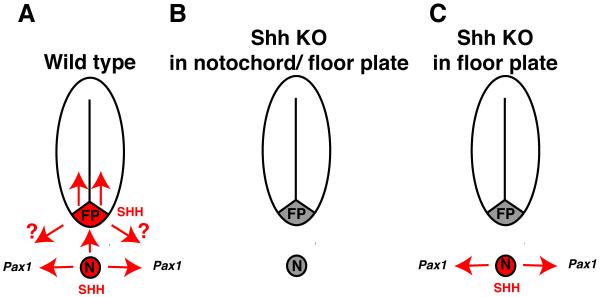

The role the notochord plays in embryonic patterning during early development has been extensively investigated. In this report we demonstrate that the patterning of two later developing tissues, the nuclei pulposi and sclerotome, require Shh expression in the notochord (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Function of Shh in the vertebrate notochord.

(A) In wild type embryos, Shh expressed in the notochord maintains expression of Pax1 in the sclerotome, induces Shh expression in the floor plate and is required for patterning of the vertebral column and intervertebral discs. Shh expressed in the floor plate is required for patterning the neural tube. It is unknown if SHH secreted by the floor plate can pattern tissues outside the neural tube (“?” in figure). (B) Removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate results in a large decrease in Pax1 expression and defects in vertebral column and intervertebral disc formation. (C) Removal of Shh from the floor plate results in wild type levels of Pax1 expression and normal formation of the vertebral column and intervertebral discs. FP = floor plate, N = notochord.

In this report, we used two Cre driver lines to remove Shh expression from either the floor plate or notochord. Both of these Cre alleles, ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2, express CRE and as a result will remove Shh from the notochord and floor plate in addition to a few cells outside these tissues(Harfe et al., 2004; Park et al., 2008). The production of identical phenotypes in the vertebral column when E7.5 embryos carrying either the ShhcreERT2 or Foxa2creERT2 alleles were exposed to tamoxifen suggests that Cre expression outside the notochord did not affect the observed phenotype. These data are supported by the observation that in E9.5 Shhf/f tamoxifen-treated embryos containing the Foxa2creERT2 allele, no defects in the vertebral column or intervertebral discs were observed.

Ideally, a Cre-driver line that is only active in the notochord could be used to remove Shh expression from this tissue. Recently, a Noto-Cre allele was reported(McCann et al., 2011). While this allele should only be active in notochord precursor cells, this allele appears to drive expression in a number of tissues outside the notochord. In addition, it is not clear if the Noto:Cre line can induce recombination in all cells of the notochord.

A recent report suggested that the floor plate compensates for notochord function beginning at E10.5(Ando et al., 2011). In these experiments, loss of the notochord at E10.5 did not affect vertebral patterning or Pax1 expression in the sclerotome. Lack of a notochord at E10.5 should result in the absence of nuclei pulposi, however, the intervertebral discs were not analyzed in mice that lacked a visible notochord(Ando et al., 2011).

In the current report, we were unable to remove Shh expression only from the notochord since embryos lacking notochord Shh did not form a floor plate (see Fig. 2). Previously, we showed that removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate prior to E11.5 resulted in defects in patterning of the vertebral column(Choi and Harfe, 2011). After E11.5, Shh was not required for patterning of the vertebral column or intervertebral discs(Choi and Harfe, 2011). The data in this report indicates that Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient for patterning the intervertebral discs prior to E11.5.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate does not result in abnormal cell death in the sclerotome. Cell death was analyzed using a lysotracker assay. No ectopic cell death was observed in E11.5 embryos upon removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate (B) compared to control littermates (A). Embryos were sectioned at the forelimb level. FP = floor plate. Scale bar, 100μm.

Highlights.

Shh was removed from either the mouse floor plate or the notochord.

Shh expression in the notochord is sufficient to pattern the ventral sclerotome.

Shh expression is not required in the floor plate for sclerotome patterning.

Shh in the notochord is sufficient for patterning of the intervertebral discs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kendra McKee for technical assistance and lab support, Latanya Riley of the UF Animal Care Services for mouse husbandry and Kate Hill-Harfe for reading over the manuscript. B.D.H. was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (AG029353) and National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR055568).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, Semba K, Suda H, Sei A, Mizuta H, Araki M, Abe K, Imai K, Nakagata N, Araki K, Yamamura K. The floor plate is sufficient for development of the sclerotome and spine without the notochord. Mech Dev. 2011;128:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang SL, Rossant J. HNF-3 beta is essential for node and notochord formation in mouse development. Cell. 1994;78:561–574. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, Westphal H, Beachy PA. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KS, Cohn MJ, Harfe BD. Identification of nucleus pulposus precursor cells and notochordal remnants in the mouse: implications for disk degeneration and chordoma formation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3953–3958. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KS, Harfe BD. Hedgehog signaling is required for formation of the notochord sheath and patterning of nuclei pulposi within the intervertebral discs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9484–9489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007566108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia CL, Mahoney EJ, Durrani AA, Wylie C. Postnatal growth, differentiation, and aging of the mouse intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:447–455. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181990c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassule HR, Lewis P, Bei M, Maas R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development. 2000;127:4775–4785. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E, Ribes V, Balaskas N, Yang LL, Pierani A, Kicheva A, Novitch BG, Briscoe J, Sasai N. Dynamic assignment and maintenance of positional identity in the ventral neural tube by the morphogen sonic hedgehog. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J, Morton S, Kawakami A, Roelink H, Jessell TM. Two critical periods of Sonic Hedgehog signaling required for the specification of motor neuron identity. Cell. 1996;87:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CM, Tessier-Lavigne M. Patterning of mammalian somites by surface ectoderm and notochord: evidence for sclerotome induction by a hedgehog homolog. Cell. 1994;79:1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley EN, Jr., Herkowitz HN, Kirkpatrick JS, Wang JC, Chen MN, Kang JD. Debating the value of spine surgery. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. 2010;92:1293–1304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01439. American volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, Scherz PJ, Nissim S, Tian H, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell. 2004;118:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humzah MD, Soames RW. Human intervertebral disc: structure and function. The Anatomical record. 1988;220:337–356. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes M, Porter JA, Chiang C, Chang D, Tessier-Lavigne M, Beachy PA, Rosenthal A. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons by Sonic hedgehog. Neuron. 1995;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Laufer E, Riddle RD, Tabin C. Ectopic expression of Sonic hedgehog alters dorsal-ventral patterning of somites. Cell. 1994;79:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21–24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01273. American volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann MR, Tamplin OJ, Rossant J, Seguin CA. Tracing notochord-derived cells using a Noto-cre mouse: implications for intervertebral disc development. Dis Model Mech. 2011 doi: 10.1242/dmm.008128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza SK, Deyo RA. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:816–823. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000259225.37454.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh LC, Chyung JH, Lassar AB. Sonic hedgehog promotes somitic chondrogenesis by altering the cellular response to BMP signaling. Genes & development. 1999;13:225–237. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Sun X, Nichol P, Saijoh Y, Martin JF, Moon AM. System for tamoxifen-inducible expression of cre-recombinase from the Foxa2 locus in mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:447–453. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelink H, Porter JA, Chiang C, Tanabe Y, Chang DT, Beachy PA, Jessell TM. Floor plate and motor neuron induction by different concentrations of the amino-terminal cleavage product of sonic hedgehog autoproteolysis. Cell. 1995;81:445–455. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Nerurkar NL, Choi KS, Harfe BD, Elliott DM. Degeneration and regeneration of the intervertebral disc: lessons from development. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:31–41. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley R. The development and growth of the intervertebral disc. Edinburgh Med J. 1953;60:341–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods in enzymology. 1993;225:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Nakamura E, Nguyen MT, Bao X, Akiyama H, Mackem S. Uncoupling Sonic hedgehog control of pattern and expansion of the developing limb bud. Dev Cell. 2008;14:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate does not result in abnormal cell death in the sclerotome. Cell death was analyzed using a lysotracker assay. No ectopic cell death was observed in E11.5 embryos upon removal of Shh from the notochord and floor plate (B) compared to control littermates (A). Embryos were sectioned at the forelimb level. FP = floor plate. Scale bar, 100μm.