Abstract

Hypertension and type 2 diabetes (T2D) commonly coexist, and both conditions are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). We aimed to examine the association between genetic predisposition to high blood pressure and risk of CVD in individuals with T2D. The current study included 1,005 men and 1,299 women with T2D from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study and Nurses’ Health Study, of whom 732 developed CVD. A genetic predisposition score was calculated on the basis of 29 established blood pressure–associated variants. The genetic predisposition score showed consistent associations with risk of CVD in men and women. In the combined results, each additional blood pressure–increasing allele was associated with a 6% increased risk of CVD (odds ratio [OR] 1.06 [95% CI 1.03–1.10]). The OR was 1.62 (1.22–2.14) for risk of CVD comparing the extreme quartiles of the genetic predisposition score. The genetic association for CVD risk was significantly stronger in patients with T2D than that estimated in the general populations by a meta-analysis (OR per SD of genetic score 1.22 [95% CI 1.10–1.35] vs. 1.10 [1.08–1.12]; I2 = 71%). Our data indicate that genetic predisposition to high blood pressure is associated with an increased risk of CVD in individuals with T2D.

Patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) have a two- to fourfold higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) than nondiabetic people (1). Many conditions that coexist with T2D, such as high blood pressure, also contribute to CVD risk (2). It has been suggested that up to 75% of CVD in patients with diabetes may be attributable to high blood pressure (2–4). Blood pressure is a heritable trait influenced by multiple genetic factors (5). Recently, 29 independent genetic variants were indentified as associated with systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure by the International Consortium for Blood Pressure genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with a multistage design in ∼200,000 individuals of European descent (5). A genetic risk score based on these 29 genetic variants was also reported to be associated with hypertension and CVD risk in general populations (5). We and others have shown that diabetes-related metabolic derangements may modify genetic effects on CVD risk (6,7). However, whether the effects of blood pressure–associated variants on CVD risk differ in patients with T2D is unknown. In addition, many dietary and lifestyle risk factors for hypertension have been identified (8), such as BMI, physical activity, the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, alcohol intake, use of nonnarcotic analgesics, and supplemental folic acid intake. It is unknown whether these dietary and lifestyle risk factors influence the association between the high blood pressure–predisposing variants and CVD risk.

Therefore, we constructed a genetic predisposition score on the basis of 29 high blood pressure–predisposing variants and examined the association between the genetic predisposition score and risk of CVD among men and women with T2D from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and Nurses’ Health Study (NHS). We also compared our findings in patients with T2D with those in the general population, assessed by meta-analysis.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The HPFS is a prospective cohort study of 51,529 U.S. male health professionals who were 40–75 years of age at study inception in 1986 (9). Between 1993 and 1999, 18,159 men provided blood samples. The NHS is a prospective cohort study of 121,700 female registered nurses who were 30–55 years of age at study inception in 1976 (10). A total of 32,826 women provided blood samples between 1989 and 1990. In the current analysis for the NHS, 1980 was defined as the baseline year because diet was first assessed since that year. In both cohorts, information about medical history, lifestyle, and disease has been collected biennially by self-administered questionnaires.

For the current study, NHS and HPFS participants were T2D case subjects who had genotype data from the NHS and HPFS T2D GWAS (11). T2D case subjects were defined according to self-reported T2D confirmed by a validated supplementary questionnaire. For case subjects before 1998, we used the National Diabetes Data Group criteria to define T2D (12), which included one of the following: one or more classic symptoms (excessive thirst, polyuria, weight loss, hunger, pruritus, or coma) plus fasting plasma glucose level of ≥7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL), random plasma glucose level of ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL), or plasma glucose level 2 h after an oral glucose tolerance test of ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL); at least two elevated plasma glucose levels (as described previously) on different occasions in the absence of symptoms; or treatment with hypoglycemic medication (insulin or oral hypoglycemic agent). The validity of this method has been confirmed (13). We used the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria for diabetes diagnosis from 1998 onward (14). These criteria were the same as those proposed by the National Diabetes Data Group except for the elevated fasting plasma glucose criterion, for which the cut point was changed from 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) to 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL).

CVD cases were defined as coronary heart disease (CHD) (fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) or stroke (fatal or nonfatal). Nonfatal myocardial infarction was confirmed by review of medical records using the criteria of the World Health Organization of symptoms plus either typical electrocardiographic changes or elevated levels of cardiac enzymes. Nonfatal stroke was confirmed by review of medical records using the criteria of the National Survey of Stroke (15). Fatal myocardial infarction and fatal stroke were confirmed by review of medical records or autopsy reports with the permission of the next of kin. Physicians blinded to risk factor status reviewed the medical records. Only diabetic patients who were diagnosed with CVD after the diagnosis of T2D through 2008 were included as cardiovascular complication case subjects. Control subjects were defined as those free of CVD after the diagnosis of T2D through 2008. Finally, a total of 1,005 men and 1,299 women with T2D of European ancestry were included: 380 men (351 CHD and 29 stroke) and 347 women (292 CHD and 55 stroke) with cardiovascular complications, and 1,572 (625 men and 947 women) non-CVD control subjects. The study was approved by the Human Research Committee at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Genotyping and imputation.

DNA was extracted from the buffy coat fraction of centrifuged blood using a commercially available kit (QIAmp Blood kit; Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). We selected 29 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure at a genome-wide significance level (Supplementary Table 1) (5). SNP genotyping and imputation have previously been described in detail (11). Briefly, samples were genotyped and analyzed using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human 6.0 array (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA) and the Birdseed calling algorithm. We used MACH (http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/MACH) to impute SNPs on chromosomes 1–22 with National Center for Biotechnology Information build 36 of Phase II HapMap CEU data (release 22) as the reference panel. Most of the SNPs included in the genetic predisposition score were directly genotyped (12 SNPs) or had a high imputation quality score (15 SNPs, MACH r2 ≥ 0.8), and 2 SNPs showed a moderate imputation quality score (rs13107325, r2 = 0.67 [HPFS] and 0.69 [NHS]; rs2521501, r2 = 0.60 [both NHS and HPFS]) (Supplementary Table 1).

Genetic predisposition score calculation.

Genetic predisposition score was calculated on the basis of the 29 SNPs by the previously reported weighted method (5,16). Each SNP was weighted by the average effect size (β-coefficient) for systolic and diastolic blood pressure obtained from the reported GWAS (5). The genetic predisposition score was calculated by multiplying each β-coefficient by the number of corresponding risk alleles and then summing the products. Because this produced a score out of 26.425 (twice the sum of the β-coefficients), the values were divided by 26.425 and multiplied by 58 (the total number of the risk alleles) to make the genetic predisposition score easier to interpret. Each point of the genetic predisposition score corresponded to each blood pressure–increasing allele.

Assessment of dietary and lifestyle factors.

Information about anthropometric data, smoking status, physical activity, menopausal status, and postmenopausal hormone therapy (women only); family history of myocardial infarction; and medical and disease history was derived from the baseline questionnaires (9,10). Participants were asked to report whether a clinician had made a diagnosis of hypertension during the preceding 2 years and were also asked whether they had undergone a physical examination or screening examination. Self-reported hypertension was shown to be highly reliable in the NHS and HPFS (17,18). In a subset of women who reported hypertension, medical record review confirmed a documented systolic and diastolic blood pressure >140 and 90 mmHg, respectively, in 100% and >160 and 95 mmHg in 77%; additionally, self-reported hypertension was predictive of subsequent cardiovascular events (17). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. For men, physical activity was expressed as METs per week by using the reported time spent on various activities, weighting each activity by its intensity level. For women, physical activity was expressed as hours per week because MET task hours were not measured at baseline in the NHS. The validity of the self-reported body weight and physical activity data has previously been described (19–21). Use of nonnarcotic analgesics (use of aspirin in the NHS and use of aspirin and acetaminophen in the HPFS) was reported on the baseline questionnaires. Alcohol intake and other detailed dietary information was collected from semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaires at baseline. The reproducibility and validity of the food-frequency questionnaires have previously been reported (22,23). Based on the diet prescribed in the DASH trial (24), a DASH score was constructed based on high intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains and low intake of sodium, sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats (25). The intake of supplemental folic acid in multivitamins or in isolated form was determined by the brand, type, and frequency of reported use.

Statistical analyses.

χ2 tests and t tests were used for comparison of proportions and means of baseline characteristics between CVD case and control subjects. We used logistic regression to estimate odd ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for CVD risk, adjusting for age and BMI. In multivariable analysis, we further adjusted for family history of myocardial infarction (yes or no), smoking (never, past, or current), menopausal status (pre- or postmenopausal [never, past, or current hormone use] [women only]), physical activity (quartiles), alcohol intake (0, 0.1–4.9, 5.0–9.9 10.0–14.9 or ≥ 15.0 g/day), DASH diet score (quartiles), nonnarcotic analgesics use (yes or no), and supplemental folic acid use (yes or no). Results in women and men were pooled by using inverse variance weights under a fixed model, as there was no heterogeneity. Linear relation analysis between the genetic predisposition score (as continuous variables) and risk of CVD was performed by using a restricted cubic spline regression model (26). In secondary analyses, we tested whether the association between the genetic predisposition score and risk of CVD was modified by self-reported hypertension status, BMI, physical activity, DASH diet score, alcohol intake, use of nonnarcotic analgesic, and use of supplemental folic acid using analyses stratified by these factors and by including the respective interaction terms in the models. Similar analyses were repeated for the association between the genetic predisposition score and CHD risk. In addition, we performed a meta-analysis to compare the result in patients with T2D with that in general populations (i.e., participant groups not restricted to patients with diabetes). All reported P values are nominal and two side. Statistical analyses were performed in STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) or SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of study participants.

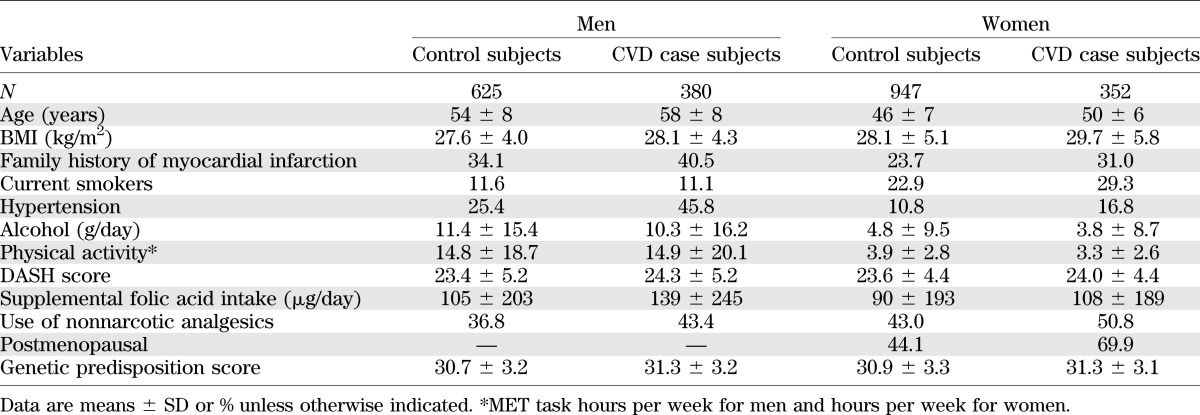

Table 1 shows the characteristics of study participants. Among diabetic men and women, CVD case subjects were older, had higher BMI, consumed less alcohol, and were more likely to have a family history of myocardial infarction, have self-reported hypertension, and use nonnarcotic analgesics than non-CVD control subjects.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics among 1,005 men and 1,299 women with T2D

The genetic predisposition score ranged from 18.1 to 40.8, and the mean ± SD was 31.0 ± 3.2 in both women and men. After adjustment for age and BMI, the genetic predisposition score was significantly associated with self-reported hypertension in both men and women. The ORs associated with each additional point of the score, which corresponds to one additional blood pressure–increasing allele, were 1.09 (95% CI 1.05–1.14) in men and 1.05 (1.01–1.09) in women.

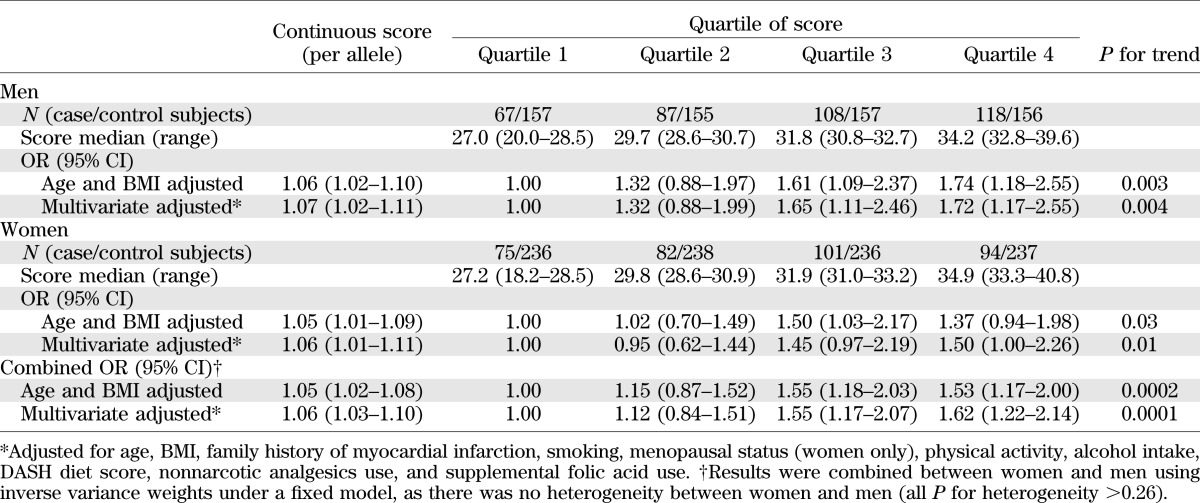

Genetic predisposition score and CVD risk.

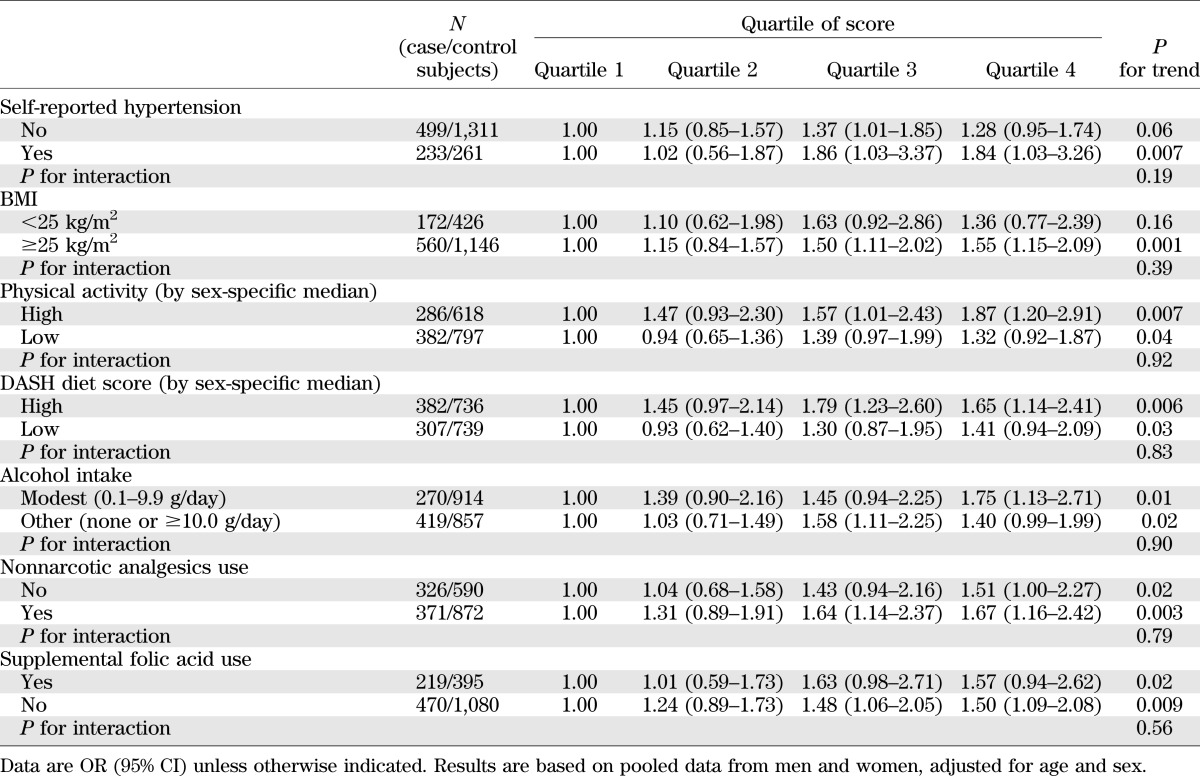

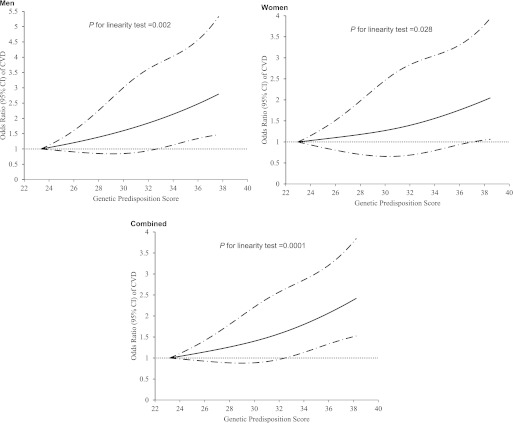

As shown in Table 2, the ORs for CVD risk were 1.06 (95% CI 1.02–1.10) and 1.05 (1.01–1.09) with each additional point of the genetic predisposition score in diabetic men and women, respectively, adjusted for age and BMI. Multivariable adjustment did not change the associations. With no sex differences in ORs (all P for heterogeneity >0.26), we combined the results from men and women by using meta-analysis under a fixed-effects model. Each additional point of the genetic predisposition score was associated with a 6% increased risk of developing CVD (OR 1.06 [95% CI 1.03–1.10]), adjusted for age, BMI, and other dietary and lifestyle risk factors. The ORs for CVD risk significantly increased across the quartiles of the genetic predisposition score (P for trend = 0.0001). Compared with those in the lowest quartile, participants in the highest quartile of the genetic predisposition score had an OR of 1.62 (95% CI 1.22–2.14), adjusted for age, BMI, and other dietary and lifestyle risk factors. The association was attenuated but remained significant after further adjustment for self-reported hypertension (P for trend = 0.002). We further examined the association between the genetic predisposition score and CVD risk stratified by baseline hypertension status (Table 3). Although the association was more pronounced in patients with hypertension than in those without hypertension, there was no significant interaction (P for interaction = 0.19). In addition, we also used a restricted cubic spline regression model to investigate the association continuously (Fig. 1). The genetic predisposition score showed a linear relationship with increasing risk of CVD (P for linearity = 0.002, 0.028, and 0.0001 in men, women, and men and women combined, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Association between the genetic predisposition score and CVD risk in patients with T2D

TABLE 3.

Stratified analysis of the genetic predisposition score and CVD risk

FIG. 1.

Linear relationship between blood pressure genetic predisposition score and risk of CVD. Data are OR (solid lines) and 95% CI (dashed lines), adjusted for age, BMI, family history of myocardial infarction, smoking, menopausal status (women only), physical activity, alcohol intake, DASH diet score, nonnarcotic analgesics use, and supplemental folic acid use.

Results were similar when the outcome was restricted to CHD. The ORs for CHD risk per blood pressure–increasing allele were 1.07 (95% CI 1.02–1.12) and 1.05 (1.00–1.10) in diabetic men and women, respectively, adjusted for age, BMI, and other dietary and lifestyle risk factors. In the combined results of men and women, the multivariable-adjusted OR was 1.55 (1.16–2.07) for CHD risk by comparing extreme quartiles of the genetic predisposition score (P for trend = 0.0002). Restricted cubic spline regression analysis also showed that there was a linear relationship between the genetic predisposition score and CHD risk (P for linearity = 0.0007).

Stratified analyses by dietary and lifestyle risk factors.

We next examined whether the association between the genetic predisposition to high blood pressure and CVD risk varied across subgroups of the population stratified by dietary and lifestyle risk factors for hypertension. In combined results from men and women, we observed consistent associations across subgroups of the population stratified by BMI, physical activity, DASH diet score, alcohol intake, nonnarcotic analgesics use, and supplemental folic acid use (Table 3). There was no significant interaction between the genetic predisposition score and these dietary and lifestyle risk factors (all P for interaction >0.39). Results were similar in both sexes when we performed analyses in men and women separately (data not shown).

Genetic effects in patients with diabetes compared with general populations.

We then compared our results in patients with T2D with data in general populations (i.e., participant groups that were not restricted to patients with diabetes) (Fig. 2). We used fixed-effects meta-analysis to combine the risk ratios for CVD (stroke or CHD) previously reported in such populations (5) and the risk ratios derived from a GWAS of CHD performed in nondiabetic participants of HPFS and NHS (Supplementary Data) (27). The risk ratios per SD of the genetic predisposition score were approximately 1.1 among these studies, with a combined risk ratio of 1.10 (95% CI 1.08–1.12) and no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). We recalculated the CVD risk per SD of the genetic predisposition score in our T2D patients and observed a stronger effect of the genetic predisposition score on CVD risk (OR 1.22 [95% CI 1.10–1.35]) compared with that in the general populations. The associations between the genetic predisposition score and CVD risk showed significant heterogeneity between the diabetic and the general populations (I2 = 71%, P for heterogeneity = 0.045).

FIG. 2.

CVD risk per SD of the genetic predisposition score in patients with T2D and general populations. Risk ratios (RRs) per SD of the genetic predisposition score are given as hazard ratio in the NEURO-CHARGE study and ORs in other studies. The cardiovascular outcomes were stroke in the NEURO-CHARGE and SCG; CHD in the HPFS-NHS_CHD, CARDIoGRAM, C4D ProCARDIS, and C4D HPS; and CHD and stroke in patients with T2D from the HPFS and NHS. The RRs in the general populations (participant groups not restricted to patients with diabetes) were derived from a previous study (5), except for in the case of HPFS-NHS_CHD.

DISCUSSION

In two independent studies of men and women with T2D, we examined the association between a genetic predisposition score, composed of 29 independent high blood pressure–predisposing variants, and risk of CVD. Our highly consistent results in men and women indicate that the genetic predisposition to high blood pressure may significantly increase risk of cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients, independent of dietary and lifestyle risk factors for hypertension.

Because each individual SNP may have a moderate genetic effect and only explain a small proportion of the variation of blood pressure, we examined the collective contribution of the multiple genetic variants by computing a genetic predisposition score, which emphasized the overall genetic susceptibility to high blood pressure. As greater genetic variance was explained by multiple variants, the genetic predisposition might be estimated more accurately by using this approach. In diabetic patients, each additional blood pressure–increasing allele in the genetic predisposition score was associated with a 6% increased risk of CVD. By accumulation, individuals in the highest quartile of the score had a 60% greater risk of developing CVD than those in the lowest quartile. Therefore, this approach provides a broader characterization of the individual’s genetic risk profile, which may be useful for identifying a substantial proportion of people with a high genetic risk of CVD.

High blood pressure is one of the most important risk factors for CVD risk in patients with T2D (2–4). That the observed genetic associations should be unaffected by confounding from environmental factors and free of reverse causation (28) suggests that there is a casual relationship between the genetic predisposition to high blood pressure and increased risk of CVD. This is in line with the fact that hypertension plays a casual role in the development of CVD, which has been supported by several controlled clinical trials indicating that control of blood pressure significantly reduces the cardiovascular complications in patients with T2D (29–35), although it remains debatable whether tight control of blood pressure offers additional benefits in the reduction of cardiovascular risk compared with usual control of blood pressure (35–37).

One of our novel findings is that the association between the high blood pressure genetic predisposition score and risk of CVD was significantly stronger in patients with T2D than that previously reported in various general populations (5). In the general population, each additional SD of the genetic predisposition score may increase CVD risk by ∼10%, while the increment of CVD risk per SD of the genetic predisposition score was 22% in patients with T2D. This finding is consistent with some previous data from clinical trials in which blood pressure–lowering reduced the rate of CVD events more in patients with T2D than in those without diabetes (31,33). Given a comparable amount in reduction of systolic blood pressure, the risk reduction in CVD mortality was 76% in diabetic patients versus 13% in those without diabetes (33). Moreover, the effect of the genetic predisposition score of high blood pressure on CVD risk was even stronger than our previously observed effect of the T2D genetic predisposition score (∼3% increased CVD risk per diabetes risk allele) in the same diabetic populations. Consistently, in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study, blood pressure control was found to be more effective than glycemic control at reducing cardiovascular events in patients with T2D (29). Our current genetic association study lends support to this notion and also suggests that diabetic patients with a higher hypertension genetic predisposition score may need more blood pressure management to reduce CVD risk, although the optimal blood pressure goal for diabetic patients remains unknown (35–37).

The major strengths of our study include the consistent findings in two independent studies of diabetic patients, high-quality data of multiple genetic variants, and minimal population stratification (11). Several limitations need to be acknowledged. Blood pressure levels were not measured in our study samples; thus, we did not test the association between the genetic predisposition score and blood pressure, but we confirmed the association with hypertension in patients with T2D. The associations of these genetic variants with hypertension and blood pressure have been well established in the previous GWAS (5). Although our genetic predisposition score captured the combined information from the established genetic variants for blood pressure thus far, it may account for only a small amount of variation of blood pressure (5). Because of the relative small number of stroke case subjects, we did not perform the association analysis for stroke risk separately. However, we observed similar genetic effect on risk of CVD (stroke and CHD) and CHD. The previously reported results for risk of stroke and coronary artery disease were also similar in the general populations (5). In addition, our study only includes diabetic patients of European ancestry, and it remains to be examined whether the results are generalizable to other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, we found that the genetic predisposition to high blood pressure was significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications among men and women with T2D, independent of dietary and lifestyle risk factors. The observed genetic association in diabetic patients was stronger than that in the general populations. These results improve our understanding of the genetic predisposition to high blood pressure and risk of CVD and also support the causal role of high blood pressure in the development of CVD. Treatment of high blood pressure is important and needs to be a therapeutic priority in patients with T2D, particularly in those with a high genetic risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants HL071981, HL073168, CA87969, CA49449, HL34594, HL088521, U01HG004399, DK080140, DK58845, and DK46200 from the National Institutes of Health. L.Q. is a recipient of the American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (0730094N).

The genotyping of the HPFS and NHS CHD GWAS was supported by an unrestricted grant from Merck Research Laboratories (North Wales and Pennsylvania). No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Q.Q. designed the study, researched data, and wrote the manuscript. J.P.F., M.K.J., A.F., G.C.C., E.B.R., and F.B.H. contributed to discussion and edited and reviewed the manuscript. L.Q. designed the study, reviewed data, contributed to discussion, and edited and reviewed the manuscript. L.Q. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank all the participants of the NHS and the HPFS for their continued cooperation.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db12-0225/-/DC1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almdal T, Scharling H, Jensen JS, Vestergaard H. The independent effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on ischemic heart disease, stroke, and death: a population-based study of 13,000 men and women with 20 years of follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1422–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sowers JR, Epstein M, Frohlich ED. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: an update. Hypertension 2001;37:1053–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long AN, Dagogo-Jack S. Comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011;13:244–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell NR, Leiter LA, Larochelle P, et al. Hypertension in diabetes: a call to action. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:299–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, et al. International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies. CARDIoGRAM consortium. CKDGen Consortium. KidneyGen Consortium. EchoGen consortium. CHARGE-HF consortium Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature 2011;478:103–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi Q, Workalemahu T, Zhang C, Hu FB, Qi L. Genetic variants, plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among two prospective cohorts of type 2 diabetes. Eur Heart J 2012;33:325–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doria A, Wojcik J, Xu R, et al. Interaction between poor glycemic control and 9p21 locus on risk of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2008;300:2389–2397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA 2009;302:401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet 1991;338:464–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health 1997;6:49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi L, Cornelis MC, Kraft P, et al. Meta-Analysis of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium (MAGIC) Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium Genetic variants at 2q24 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:2706–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 1979;28:1039–1057 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of maturity-onset diabetes mellitus and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1141–1147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1183–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker AE, Robins M, Weinfeld FD. The National Survey of Stroke. Clinical findings. Stroke 1981;12(Suppl. 1):I13–I44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornelis MC, Qi L, Zhang C, et al. Joint effects of common genetic variants on the risk for type 2 diabetes in U.S. men and women of European ancestry. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:541–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123:894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, et al. A prospective study of nutritional factors and hypertension among US men. Circulation 1992;86:1475–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, et al. Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117:651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1990;1:466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–1126; discussion 1127–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:51–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. DASH Collaborative Research Group A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 1989;8:551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen MK, Pers TH, Dworzynski P, Girman CJ, Brunak S, Rimm EB. Protein interaction-based genome-wide analysis of incident coronary heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2011;4:549–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter DJ, Altshuler D, Rader DJ. From Darwin’s finches to canaries in the coal mine—mining the genome for new biology. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2760–2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998;317:703–713 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ 1998;317:713–720 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. HOT Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Niskanen L, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition compared with conventional therapy on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, et al. Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med 1999;340:677–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G, The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000;342:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA 2010;304:61–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. ACCORD Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1575–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reboldi G, Gentile G, Manfreda VM, Angeli F, Verdecchia P. Tight blood pressure control in diabetes: evidence-based review of treatment targets in patients with diabetes. Curr Cardiol Rep 2012;14:89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]