Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a human pathogen and a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. New antibacterial agents that have not been compromised by bacterial resistance are needed to treat MRSA-related infections. We chose the S. aureus cell wall synthesis enzyme, alanine racemase (Alr) as the target for a high-throughput screening effort to obtain novel enzyme inhibitors, which inhibit bacterial growth. Among the ‘hits’ identified was a thiadiazolidinone with chemical properties attractive for lead development. This study evaluated the mode of action, antimicrobial activities, and mammalian cell cytotoxicity of the thiadiazolidinone family in order to assess its potential for development as a therapeutic agent against MRSA. The thiadiazolidones inhibited Alr activity with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) ranging from 0. 36 – 6. 4 μM, and they appear to inhibit the enzyme irreversibly. The series inhibited the growth of S. aureus, including MRSA strains, with minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 6. 25–100 μg/mL. The antimicrobial activity showed selectivity against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi, but not Gram-negative bacteria. The series inhibited human HeLa cell proliferation. Lead development centering on the thiadiazolidinone series would require additional medicinal chemistry efforts to enhance the antibacterial activity and minimize mammalian cell toxicity.

Keywords: D-alanine, alanine racemase, peptidoglycan, MRSA

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a human pathogen that causes a variety of infections ranging from minor skin sepsis to potentially fatal bacteremia [1]. Once successfully managed with methicillin, these infections became difficult to treat with the emergence of MRSA strains that are resistant to virtually all β-lactam antibiotics. Previously confined to healthcare settings, MRSA strains are now frequently found in the community, and curbing the spread of this pathogen has become a considerable challenge [2]. Compounding this problem is the propensity of MRSA strains to acquire multiple drug resistance. Reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, the current antibiotic of choice for S. aureus infections, is frequently encountered among clinical isolates [3]. Given the potentially limited MRSA treatment options coupled with widespread occurrence and evolving resistance patterns, there is an urgent need for the discovery of effective MRSA drugs that act on new bacterial targets.

Alanine racemase (Alr), a pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme, is an important target for developing new antibiotics as it is a key enzyme in bacterial cell wall synthesis [4]. It catalyzes the racemization of L-alanine to D-alanine, which is an essential precursor for the synthesis of the pentapeptide moiety that cross-links the glycan chains in peptidoglycan [5]. In S. aureus, D-alanine is also incorporated into teichoic acids, which are unique cell wall polysaccharides necessary for virulence [6, 7]. Since peptidoglycan and teichoic acids are unique to prokaryotes, the majority of the enzymes involved in their synthesis, including Alr, lack homologs in humans. As such, these enzymes are also attractive as targets for the discovery of highly selective antibiotics.

In the case of Alr, numerous enzyme inhibitors have been identified though none are selective. These include cycloserine, o-carbamyl-D-serine, β,β,β-trifluoroalanine, alanine phosphonate, 1-amino-cyclopropane phosphonate, and β-chloro- and β-fluoroalanine [8–14]. All of these inhibitors are structural analogs of alanine, which by virtue of their primary amines, interact with the enzyme-bound PLP and interfere with the catalytic process of the enzyme. Often, these inhibitors lack target-specificity with a tendency to inactivate other unrelated PLP-dependent enzymes leading to cellular toxicity [15]. Conceivably, Alr inhibitors that are not substrate analogs could overcome some of the PLP-related off-target effects.

In an attempt to obtain non-substrate-like Alr inhibitors with structural attributes desirable for drug development, we screened a diverse collection of small molecule libraries for Alr enzyme inhibitors. Among the hits were molecules that are structurally unrelated to alanine and lack the PLP-modifying primary amine. One such molecule was a thiadiazolidinone, which we termed L2-401, with chemical properties attractive for lead development. Here, we report: potential mechanisms by which L2-401 inhibits Alr activity; its antimicrobial activity against a panel of S. aureus strains, and a panel of unrelated bacteria and fungi; its effects on mammalian cell proliferation; as well as an assessment of its potential for development as an antibacterial agent.

2. Materials and Methods

2. 1. Test organisms

The 11 S. aureus strains used in this study are strains 328 (ATCC 33591), HFH-29568 (ATCC BAA-1680), HFH-30364 (ATCC BAA-1683), HFH-30522 (ATCC BAA-1684), HFH-30032 (ATCC BAA-1688), PCI 1158 (ATCC 14775), FDA 209 (ATCC 6538-1), PCI 124 (ATCC 13150), 102-04 (ATCC BAA-1765-1), S. aureus N315 (accession # BA000018) and USA300 (accession # CP000255). The bacterial and fungal test isolates used in the antimicrobial activity spectrum analysis (Table 3) were from Micromyx collection (Kalamazoo, MI) or reference strains from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial activity spectrum of L2-401, Ciprofloxacin, and Amphotericin B against bacterial, yeast, and fungal isolates

| MIC (μg/mL)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | L2-401 | Ciproa | AMPBb |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis 831 | 8 | >16 | >64 |

| Enterococcus faecalis 101 | 32 | 0. 5 | >64 |

| Enterococcus faecium 800 | 32 | >16 | >64 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae 1195 | 32 | 0. 5 | >64 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes 712 | >64 | 0. 25 | >64 |

| Escherichia coli 102 | >64 | 0. 004 | >64 |

| Escherichia coli 120c | >64 | 0. 008 | >64 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 1339 | >64 | 0. 25 | >64 |

| Proteus mirabilis 1360 | >64 | 0. 03 | >64 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1380 | >64 | 4 | >64 |

| Candida albicans 2000 | 2 | >64 | ≤ 0. 06 |

| Aspergillus niger 624 | 16 | >64 | 0. 25 |

Ciprofloxacin

Amphotericin B

acrAB efflux pump deletion

2. 2. Test media

The medium used for most bacterial isolates was Mueller Hinton II broth or Trypticase Soy broth (TSB). For testing of streptococci, the medium was supplemented with 3% laked horse blood (Cleveland Scientific Lot No. 93321). The medium employed for the Candida and Aspergillus isolates was RPMI-1640 (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT). The media were prepared as described in guidelines published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).

2. 3 Chemicals

Small molecule compounds were purchased from ChemDiv (San Diego, CA). D-alanine, L-alanine, L-alanine dehydrogenase (Bacillus subtilis), PLP, and β-NAD-sodium salt, cycloserine, sodium propionate, and O-acetyl-L serine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tricine and Tris were purchased from American Bioanalytical (Natick, MA).

2. 4. Cloning, expression and purification of recombinant S. aureus Alr

The alr gene of S. aureus MRSA 252 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_002952. 2) was used as the template for constructing a synthetic DNA expression construct, encoding the 383-amino acid Alr fused to an N-terminal-hexa histidine tag (GenScript USA Inc. , Piscataway, NJ). The construct, which had codons optimal for expression in E coli, was cloned into the Xba I /Bgl II sites of pET32a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and transformed into E. coli BL21-DE3 (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Sequence authenticity and protein expression were confirmed by DNA sequencing and pilot-scale protein expression, respectively. For larger-scale protein preparation, cells were grown at 28°C in 3 L of LB medium. When OD600 reached 0. 6, expression of alr was induced by the addition of 0. 1 mM IPTG and grown for 4 hours at 28°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with PBS, and lysed by sonication in column running buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, pH 7. 2). The enzyme cofactor, PLP was added to the cleared lysate to 0. 5 mM, which was then incubated at 4°C overnight with 5 mL Co2+-Sepharose metal affinity resin (TALON Superflow, Clontech, Mountain View CA). The resin was poured into a column and washed with 100 mL running buffer. Bound protein was eluted with 10 mL elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, pH 7. 2). Protein in the eluate was purified further by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex S200 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The S200 column buffer consisted of 25 mM Tris HCl pH 8. 0, 100 mM NaCl, and 100 μM of PLP. The eluate was monitored at 280 and 420 nm. The final yield was approximately 2 mg of purified protein per liter of culture.

2. 5. High-throughput screening (HTS) procedures

The HTS procedures have been previously described [16]. Briefly, the Esaki and Walsh Alr assay [17], in which the racemization of D- to L-alanine by Alr is coupled to the conversion of L-alanine to pyruvate and NADH by L-alanine dehydrogenase was adapted for HTS. The reaction was measured in a fluorescence plate reader that quantifies the fluorescence intensity associated with NADH. The enzyme assay was routinely performed at 25°C for 30 min. The standard reaction mixture contained 1 mM D-alanine, 1 mM NAD, 0. 13 U/mL L-alanine dehydrogenase, 10 mM Tricine pH 8. 5. The reaction was started by addition of purified Alr with various amounts of PLP, and NADH formation was followed by measuring fluorescence at 340 nm excitation/460 nm emission for 30 min.

For the HTS, statistical significance of a positive inhibitory signal was determined by calculating the Z’-factor for each plate as described by Zhang et al. [18], using the following formula: Z’ = 1– [3(SD signal + SD background)/(M signal – M background)], where signal is the NADH fluorescence in the negative control (Alr without substrate) and background is the NADH fluorescence in the positive control (Alr without inhibitor), SD is the standard deviation, and M is the mean. Z’-factor of >0. 5 is considered good for HTS.

HTS was performed at the National Screening Laboratory for Regional Centers of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (NSRB) at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). The libraries consisted of 229,000 small molecules, which included therapeutic compounds approved by FDA and compounds purchased from BioMol TimTec (Plymouth Meeting, PA), Prestwick (Ilkirch, France), ChemBridge (San Diego, CA), ENAMINE (Kiev, Ukraine), Maybridge (Cornwall, UK), ChemDiv (San Diego, CA), and MicroSource Diversity System’s NINDS custom collection (Gaylordsville, CT), as well as collections from the National Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School.

2. 6. Enzyme IC50 determination

For IC50 determination, five-fold dilution series of compounds (in DMSO) were prepared, and added to 30 μl of reaction cocktail in 384-well plates to yield final inhibitor concentrations of 5. 7 μg/ml, 1. 1 μg/ml, 229 ng/ml, 46 ng/ml, and 9 ng/ml. Each concentration was tested in triplicate. After a 30-minute incubation, 10 μl of D-alanine (10 mM solution) was added and fluorescence intensity was measured after a 20-minute incubation. Percent inhibition at each inhibitor concentration was calculated with respect to a positive control with no inhibitor. The results were fitted onto a sigmoidal dose-response curve using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc. , La Jolla, CA) to calculate the IC50 (compound concentration that causes 50% inhibition).

2. 7 Inhibitor reversibility assay

Reversibility of inhibition was performed by two different procedures. In the first method, L2-401 (1 μg/ml), cycloserine (10 μg/ml) and O-acetyl-L-serine (200 μg/ml), which irreversible and reversible inhibitors, respectively were pre-incubated with the enzyme (0. 11 μg/ml). Aliquots were removed after 30 minutes, 6 hours and 16 hours of incubation and Alr assays were performed to determine the enzyme IC50s as described above. In the second method, the enzyme-inhibitor mixture was placed in 96-well microdialysis plate with a molecular weight cutoff of 10000 (Pierce, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and dialyzed (10 mM Tricine, pH 8. 5) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In this experiment, sodium propionate (2 mg/ml) was used as the reversible inhibitor control. Aliquots were withdrawn after 4 and 16 hours and Alr activity was determined. Percent enzyme activity remaining was calculated with respect to a control without inhibitor.

2. 8. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESMS) and comparative MALDI-MS

ESMS was performed to detect direct interactions of the inhibitor with the enzyme. A mixture of 15 μl of sample (4 μM Alr with 1 mM inhibitor) was diluted with 15 μl 2% acetonitrile/ 0. 1% formic acid. Samples were then de-salted using C4 ZipTips, eluted into 15 μl 60% acetonitrile/ 0. 1% formic acid, and directly injected into a Qtof-micro MS instrument (Waters Corp. , Milford, MA). To identify potential modified residues, samples were prepared as described for the ESMS. Five microliter of the desalted material was denatured in 8 M urea/0. 4 M NH4HCO3 (Sigma Aldrich), alkylated with 14 mM iodoacetic anhydride (Sigma Aldrich), digested overnight with trypsin, 1:25 (Sigma Aldrich), and kept frozen until further use. The samples were analyzed by MALDI-MS on a MDS SCIEX 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

2. 9. S. aureus minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) studies

The MIC of the compound necessary to inhibit bacterial growth was determined by the broth microdilution method according to the CLSI standards [19]. Briefly, an overnight culture of S. aureus grown in TSB was diluted 1:50 and grown with shaking at 37°C until OD600 reached 0. 3. Inhibitors (5 mg/ml dissolved in 100% DMSO) were 2-fold serially diluted in growth medium, and added to the wells. The plates were incubated at 37°C, and growth was inspected 16–24 hours later. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of compound that did not yield visible turbidity.

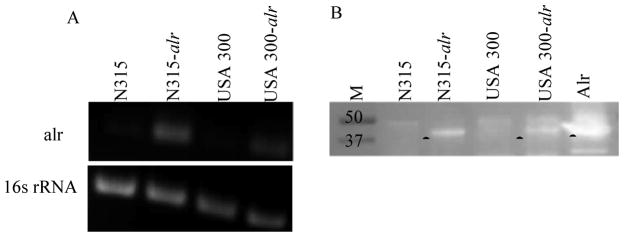

2. 10. Construction of two S. aureus strains overexpressing Alr

Overexpression of alr was performed by using a construct encompassing the completealr gene (1148 bp) as well as the upstream region (302 bp) including the putative ribosomal binding site and promoter usingthe alr primers alr-F (5’-ACTGAGCATTATGCGATGAGCCA -3’) and alr-R (5’-GCTTCGTTCGCTAGGGAGAG-3’) and by using DNA from S. aureus N315 (accession # BA000018) and S. aureusUSA300 (accession# CP000255) as template. The 1. 45 kb PCR fragment products were purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit, ligated into the ligase-independent cloning site of the PCR2. 1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and transformed into chemically competent TOP10 E. coli(Invitrogen). A staphylococcal origin of replication was introduced by cloning plasmid psK265S. aureus replicon [20]into the unique BamHIsite on PCR 2. 1 -TOPO (pMPRF-4). T he construct was moved into S. aureusRN4220 by electroporation [21]. Over expression of alr was obtained by phage 80α-mediatedtransduction of the pPSK-2 vector containing wild-type RN4220 alrinto S. aureusN315 and USA 300 [22]. These mutants were named N315-alrand USA300 -alr. Overexpression of alrin these strains were confirmed by semi - quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting. For RT-PCR, total RNA from exponentially growing cells was obtained using the Qiagen RNA PurificationKit (Qiagen Inc. , Valencia CA), and cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA); according to manufacturer’s instructions. A 200-bp fragment in thealr gene was amplified using primers alr1 (5’-TAGATAATCATAGAGAAAGTCC-3’) and alr2 (5’-CATCATGATAGATTCGCGGCA-3’). The internal control 16s rRNA was amplified using primers 16S1 (5’-GTGAATACGTTCCCGGGTCT-3’) and 16S2 (5’-GCACCTTCCGATACGGCTAC-3’). For western blot analyses, protein lysates from exponentially growing cells were preparedwith BPER (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and quantified by OD280. Approximately 10 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulosemembranes and probed with 1:20,000 rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against the S. aureusAlr. Membranes were developed with ECL Plus Blotting Detection System (Amersham/GE Healthcare).

2. 11. HeLa cell proliferation studies

The human HeLa cell line (CCL-2, ATCC, Manassas, VA) was grown overnight to confluence (37°C, 5% CO2) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The following day, 3000 cells were plated into each well of a 96-well plate and grown overnight. Compounds diluted in culture medium were added to the cells to yield final concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12. 5, and 6. 25 μg/ml. The cells were exposed to the compounds for 48 hours, after which compound-induced anti-proliferative effects on cells was determined using the WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to manufacturer’s protocols. Absorbance at 450 nm was used to calculate percent cytotoxicity (inhibition of cellular proliferation) with respect to a DMSO solvent control. The results were fitted onto a sigmoidal dose-response curve using Prism software to calculate the IC50 (concentration that inhibited cell proliferation by 50%).

3. Results

3. 1. Screening, triage, and discovery of the novel alanine racemase inhibitor L2-401

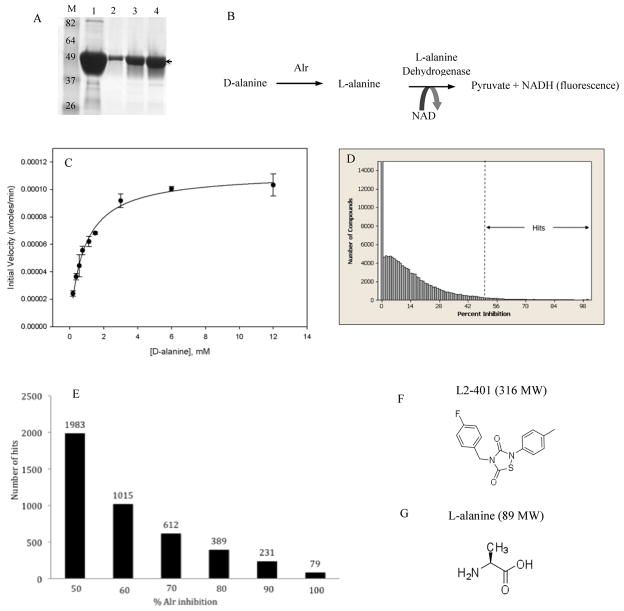

S. aureus Alr inhibitors were identified via a high-throughput screen (HTS) using purified recombinant Alr enzyme. For this purpose, a codon-optimized S. aureusalr gene was cloned and transformed into E. coli to facilitate high-level expression and to simplify the purification of enzymatically active protein (Figure 1A). Racemase activity of the purified protein was confirmed in a NADH-based fluorescent coupled enzyme assay (Figure 1B). In this assay, the reverse conversion of D to L-alanine by Alr is coupled to the deamination of the product to pyruvate by the NAD-dependent L-alanine dehydrogenase with the concomitant release of NADH. By this method, the purified recombinant S. aureus Alr was shown to be catalytically active with Km for D-alanine of 0. 82 ± 0. 06 mM and Vmax of 1. 12 x10−5 ± 2. 4 x 10−6 units (Figures 1C). The racemase assay was modified for HTS as previously described [16], and was used to screen 31 different libraries totaling 229,000 chemical compounds at a single concentration of 8 μg/ml. The overall Z’ factor for the screen, a statistical measure of the effective separation of the high and low controls ranging from 0 to 1, was >0. 6, indicating the assay was highly suitable for screening [18]. The HTS outcome is summarized in Figure 1D, which shows the distribution of the total compounds with respect to percent Alr inhibition. A hit cut-off set at >50% Alr inhibition, yielded approximately 4,300 potential hits for a hit-rate of 1. 9% (Figure 1E). These hits were then triaged on the basis of structure-based calculated properties, giving priority to those with low molecular weights, high inhibition potency, lower numbers of rotatable bonds, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, lower polar surface area, and lack of highly reactive groups [23]. This prioritization effort led to the selection of fewer than 2,000 compounds that retained Alr inhibitory activity upon retest. One of the hits that inhibited Alr by greater than 90% was L2-401 whose chemical structure is shown in Figure 1F. A member of the relatively little-studied class of heterocycles known as thiadiazolidinones, L2-401 showed no structural similarity to L-alanine (Figure 1G), and therefore, was selected for further investigation.

Figure 1. Identification of a novel S. aureus Alr inhibitor (L2-401) by HTS.

(A) Purification of recombinant S. aureus Alr. SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coommassie Blue showing materials from cobalt affinity column (lane 1) and size-exclusion chromatography (lanes 2–4). Arrow indicates the ~43,200 MW band corresponding to the monomeric Alr. M, is molecular weight markers. (B) Coupled alanine racemase assay used to determine enzyme activity. (C) Enzyme activity plot of purified Alr. (D) Summary of HTS outcome. Histogram shows the distribution of library compounds with respect to Alr inhibition and the overall proportion of ‘hits’ at the 50% inhibition cut-off. (E) Ranking of hits into five categories based on percent Alr inhibition with the total number in each category shown above the bar. Chemical structures of L2-401 (F) and L-alanine (G).

3. 2. L2-401 is likely an irreversible inhibitor of Alr

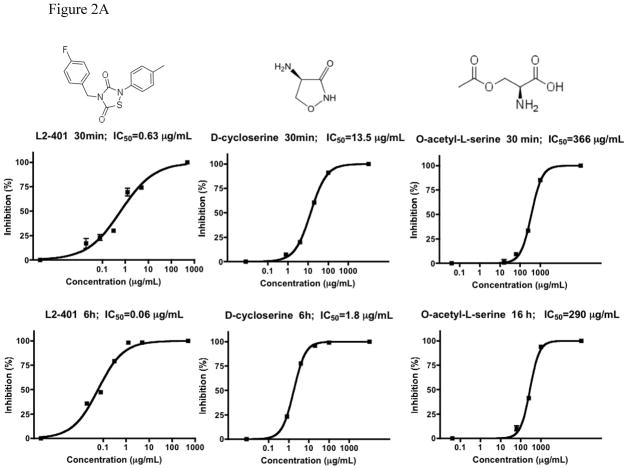

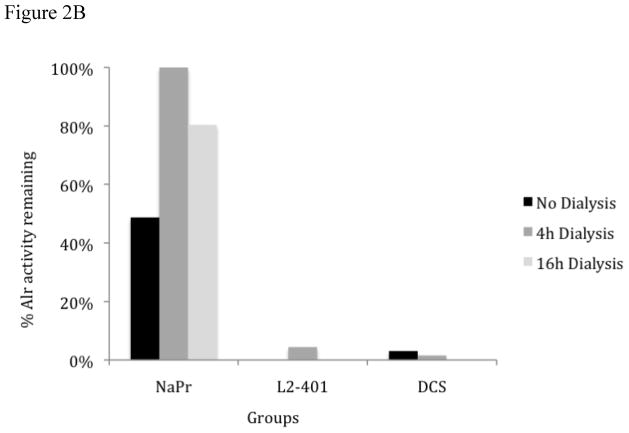

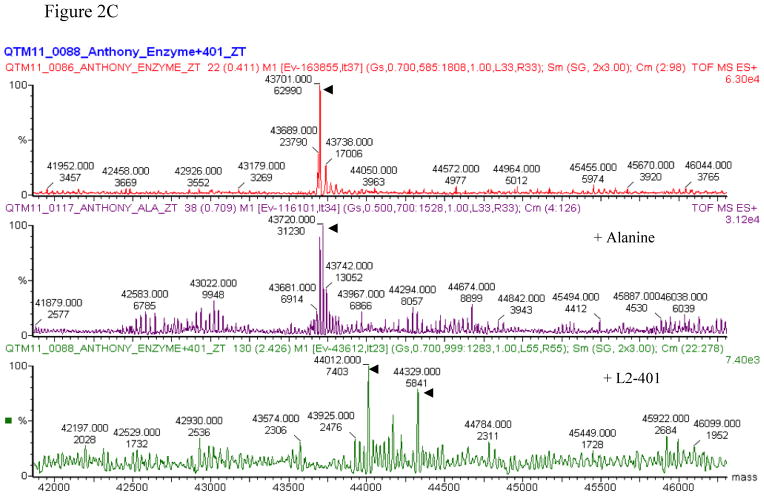

We first investigated the mechanism by which L2-401 inhibited Alr activity by assessing reversibility of the inhibition. Irreversible inhibitors often exhibit increased potency, as reflected by a decrease in the IC50 values, upon pre-incubation with the enzyme as compared to reversible inhibitors [24]. Therefore, we determined the time-dependence nature of L2-401 activity by measuring the IC50 values 30 minutes and 6 hours following pre-incubation with the enzyme. We then compared these values with those of known irreversible inhibitor, D-cycloserine and the reversible inhibitor, O-acetyl-L-serine. The results are summarized in Figure 2A. The IC50 plots for L2-401 look similar to those of D-cycloserine, in that a significant reduction in the IC50 values occurs with longer pre-incubation time. In contrast, even after 16 hours of pre-incubation, no significant reduction in IC50 values is observed for O-acetyl-L- serine. These results suggest that L2-401 likely inactivates the enzyme in an irreversible manner. To corroborate this finding, we proceeded to assess reversibility of inhibition using a commonly used method that involves pre-incubation and dilution, where the enzyme is pre-incubated with the inhibitor to form enzyme-inhibitor complex then dialyzed to reduce the inhibitor concentration below its IC50 [25]. Recovery of enzyme activity is indicative of reversible inhibition while non-recovery is suggestive of irreversible inhibition. L2-401 along with the reversible inhibitor sodium propionate [26] and cyloserine were pre-incubated with Alr for 30 minutes, upon which the mixtures were placed in a dialysis chamber and dialyzed for 16 hours. Aliquots were removed at intervals and assayed for enzymatic activity. Figure 2B shows the percent enzyme activity remaining in the undialyzed and dialyzed samples for all three inhibitors. While dialysis results in the recovery of Alr activity in the sodium propionate-treated sample, no increase in activity is seen in either the cycloserine or L2-401-treated samples, suggesting that the latter is an irreversible inhibitor.

Figure 2. L2-401-mediated inactivation of Alr.

(A) Enzyme IC50 plots at 30 and ≥6 hours post-incubation with L2-401, the irreversible inhibitor, D-cycloserine, and the reversible inhibitor, O-acetyl-L-serine. (B) Alr activity before and after dialysis of samples treated with sodium propionate (NaPr), L2-401, and D-cycloserine (DCS). (C) ESMS analysis of Alr, Alr-L-alanine, and Alr-L2-401 complex. Arrowheads indicate the peaks corresponding to monomeric Alr.

To determine the manner by which L2-401 effects the inhibition, we used mass spectrometry to detect physical changes it induces in the enzyme. L2-401 was pre-incubated with Alr, and the inhibitor-enzyme admixture was subjected to ESMS. As shown in Figure 2C, L2-401 induces an upward shift in the enzyme monomer peak. The shift corresponds to an increase in the mass of the enzyme monomer by 311 and 628 MW, suggesting that one and two molecules of the inhibitor (MW of 316), respectively, bound the enzyme. To identify the site of modification, the modified Alr was subjected to proteolytic digestion by trypsin and peptide mapping by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Peptide mapping produced more than 90% sequence coverage lacking only thirteen amino acids at the C-terminus. The MS spectra for samples with and without L2-401 were overlaid and carefully examined for peaks unique to the inhibitor-containing samples. We observed that the spectra were virtually superimposable, with no potential adduct peaks identified in the L2-401-treated sample (data not shown), revealing no stable covalent modification by the compound. Particular care was taken to investigate all cysteine-containing peptides since thiadiazolidinones are thought to potentially covalently bind to cysteine residues [27]. No compound-induced modification was observed at any of the six cysteine residues recovered in the peptide mapping. These results suggest that L2-401 likely binds the Alr enzyme irreversibly in a non-covalent manner.

3. 3 L2-401 shows selective in vitro antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity of L2-401 was examined using ten strains of S. aureus, including five MRSA strains. The MICs, measured as the minimum concentration of the inhibitor that yielded no visible growth, are summarized in Table 1. L2-401 had modest activity against S. aureus with MICs of 12. 5–25 μg/ml that were uniform against all nine strains, and similar to those of cycloserine (12. 5 μg/ml). Next, we wanted to determine if L2-401 inhibited growth by directly blocking the cellular function of Alr. The cellular effect of a particular inhibitor can often be mitigated or lessened by increasing the amount of the target. Therefore, we constructed two S. aureus mutant strains harboring multiple copies of the alr gene. The levels of alr transcript and protein in these strains were verified by RT-PCR and western blotting analysis, respectively. After confirming that the mutant strains indeed had higher levels of alr transcript and protein (Figures 3A and 3B), we measured the MICs of L2-401 in these strains. The results, which are summarized in Table 2, show no elevation of MICs in the two mutant strains, suggesting that L2-401 does not block S. aureus growth by inhibition of cellular Alr alone and that additional cellular targets might exist. A similar situation is observed for cycloserine, a known Alr inhibitor, confirming that this antibiotic has more than one bacterial cellular target as has been reported by others [28].

TABLE 1.

In vitro antibacterial activities of L2-401 and D-cycloserine (DCS) against methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains as revealed by the MIC required to inhibit bacterial growth

| MIC (μg/mL)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Strain | L2-401 | DCS |

| Staphylococcus aureus 328a | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus HFH-29568a | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus HFH-30364a | 12. 5 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus HFH-30522a | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus HFH-30032a | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus PCI 1158b | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus FDA 209b | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus PCI 124b | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus 102-04b | 25 | 12. 5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus 2012b | 32 | NDc |

Methicillin-resistant

Methicillin-susceptible

Not determined

Figure 3. S. aureus strains overexpressing Alr.

(A) Confirmation of overexpression by RNA transcript analysis by RT-PCR using primers alr1 and alr2 encompassing a 200 bp region in the alr gene. RT-PCR products from 16S rRNA were used as loading and RNA quality control. (B) Total protein analysis by western blotting using Alr-specific antisera. (●) bands corresponding to Alr, (M) molecular weight markers. Purified Alr was used a positive control.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of wild type and Alr overexpressing S. aureus strains to L2-401 and D-cycloserine (DCS)

| MIC (μg/mL)

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N315 | N315-alr | USA 300 | USA300-alr | |

| L2-401 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| DCS | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

In light of these findings, we proceeded to determine whether the antimicrobial activity of L2-401 is selective, as this information would reveal whether the effects of L2-401 could arise through general cellular toxicity. Therefore, we assessed the antimicrobial activity of L2-401 against a panel of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and fungi. Table 3 shows the MICs of L2-401 along with those of ciprofloxacin and amphotericin B, the two reference anti-bacterial and anti-fungal agents, respectively. L2-401 inhibited Gram-positive bacteria in the range of 8 to >64 μg/mL, Candida albicans at 2 μg/mL and Aspergillus niger at 16 μg/mL, but it was completely inactive against all the Gram-negative bacteria tested (MIC ≫64 μg/mL). These results indicate that L2-401 selectively inhibits Gram-positive bacteria and fungi, but not Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that the observed antimicrobial activity of L2-401 may not be due to non-specific cellular toxicity. Lack of activity against E. coli 120, a strain carrying deletion in the acrAB efflux pump, suggests that L2-401 might poorly penetrate the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria.

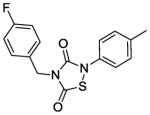

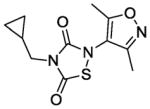

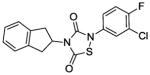

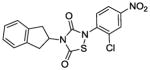

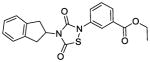

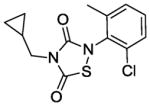

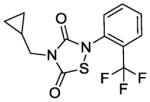

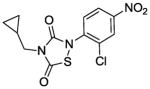

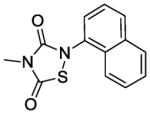

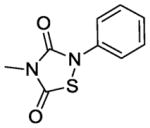

3. 4. Preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) of L2-401 family

Next, we investigated whether the observed Alr and growth-inhibitory activities of L2-401 are shared by other members of the thiadiazolinedione family. This information could validate our findings and further reveal the SAR of this family. Therefore, we obtained nine closely related L2-401 analogs, each with an intact thiadiazolinedione core, but containing various substitutions of the N-linked groups (Table 4). For each analog, we determined IC50 against recombinant S. aureus Alr, MIC against S. aureus, and IC50 in HeLa cell proliferation assay as a measure of mammalian cell toxicity. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Alr inhibition and cellular activities of L2-401 and analogs

| Compound | Structure | Alr IC50 (μM) | SA MIC (μg/mL) | HeLa IC50 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 401 |

|

2. 3 | 25 | 45 |

| 401-1 |

|

2. 9 | 100 | 22 |

| 401-2 |

|

1. 9 | 50 | 11. 9 |

| 401-3 |

|

0. 36 | 6. 25 | 2. 9 |

| 401-4 |

|

6. 4 | 25 | 23 |

| 401-5 |

|

1. 5 | 100 | 15 |

| 401-6 |

|

0. 79 | >100 | 10 |

| 401-7 |

|

0. 49 | 100 | 13 |

| 401-8 |

|

1. 5 | 100 | 26 |

| 401-9 |

|

2. 4 | 100 | 2 |

The IC50 of the nine analogs ranged from 0. 36 – 6. 4 μM with the majority being better than or comparable to the IC50 of L2-401 (2. 3 μM). Structural examination revealed that the nature of substitutions on the left side of the molecules shown in Table 4 did not markedly impact Alr inhibition, as illustrated by the relatively low IC50 values of L2-401-1 and L2-401-5 to -9, which carry smaller alkyl groups (methyl or cyclopropylmethyl) in place of the para-fluorobenzyl group in 401. This is further emphasized by very similar IC50 values (<1 μM) of L2-401-7 and 401-3, which carry dramatically different side groups, in this case, cyclopropylmethyl and 2-indanyl, respectively. On the other hand, substitutions on the right side of the N-bearing group cause a significant impact on Alr inhibition (see for example 401-3 versus 401-4). A preference for electron-poor aromatics is observed at this position, as shown by lower IC50 values of the nitro- and trifluoromethyl-substituted analogs 401-3, 401-6, and 401-7.

In terms of cellular activity, the MICs of the analogs against S. aureus ranged from 6. 25 - >100 μg/ml. Only L2-401-3 showed a lower MIC relative to the parent with the majority showing weak or no activity at all. Unlike the structural requirements for Alr inhibition, substitutions on the left-hand side of the molecule appear to have a greater impact on antimicrobial activity. For instance, when the benzyl group in L2-401 is replaced with a methyl group as in the case of L2-401-9, the cellular activity is lost. Analog L2-401-8 with a truncated left-hand side but derivatized with the larger and more lipophilic naphthyl group on the right-hand side also displayed little cell activity (MIC of 100 μg/mL). Another series of analogs in which the para-fluorobenzyl group of L2-401 is replaced with a cyclopropylmethyl group (L2-401-1, and 401-5 to 401-7), also fails to have any significant antimicrobial activity (MICs of ≥100 μg/mL).

Taken together, these results show that the structural moieties that govern Alr and growth inhibition reside on different parts of the molecule. As such, the SAR did not reveal any correlation between the two activities.

Evaluation of inhibition of HeLa cell proliferation showed that with the exception of L2-401, all of the analogs had HeLa cell IC50 values well below the MIC values. These results suggest that the L2-401 series generally inhibit HeLa cell proliferation, and could prove to be toxic to mammalian cells. It should be noted that cytotoxicity did not directly correlate with MICs (e. g. , compound 401-9 was quite cytotoxic with low IC50 but only had weak antibacterial activity with high MIC).

4. Discussion

Given its importance in the construction of cell wall peptidoglycan and teichoic acid, the biosynthesis of D-alanine is an attractive antibiotic target in S. aureus. We have performed a HTS with the S. aureus D-alanine biosynthetic enzyme Alr, and have identified L2-401 as a novel class of Alr inhibitor. As a thiadiazolidinone, L2-401 is not an alanine analog, and therefore, likely interacts with Alr in a manner distinct from that of known inhibitors. Our studies revealed that L2-401 directly binds Alr and irreversibly inhibits it in a time-dependent manner. Additional findings revealed that L2-401 shows selectivity for alanine racemases from different bacterial species. For instance, the inhibitor is highly active against the Alrs from S. aureus and M. tuberculosis, but not against the homolog from B. anthracis (Ciustea and Anthony, unpublished data). The molecular mechanism by which L2-401 inhibits S. aureus Alr is yet to be worked out completely. Nevertheless, its structural features, including the lack of primary amines and the size, suggest that it is unlikely to interact with the enzyme-bound PLP cofactor or to occupy the substrate-binding site due to spatial constraints. Therefore, L2-401 is likely an allosteric inhibitor of Alr. It has been suggested that in general thiadiazolidinones covalently inactivate enzymes by nucleophilic attack of cysteine residues [27]. However, the mass spectrometry results, which revealed no covalent modification of the cysteine residues by L2-401, suggested a non-covalent interaction between the inhibitor and the enzyme. Efforts to co-crystallize L2-401 with the enzyme are currently underway to determine the exact mechanism of action of the inhibitor.

L2-401 demonstrated antimicrobial activity against S. aureus. All nine strains, including MRSA strains, were uniformly susceptible to this compound. Growth inhibition, however, does not appear to arise solely from inhibition of cellular Alr as the effect could not be mitigated by overexpression of the enzyme. Analysis of antimicrobial activity spectrum of L2-401 revealed that this inhibitor was not active against Gram-negative bacteria, but was active against Gram-positive and two fungal species. Although Alr homologs exist in the latter two species, whether the observed MICs are a direct consequence of inhibition of this enzyme is not known [29–31]. Nevertheless, our overall findings are consistent with the general antibacterial and antiviral properties of thiadiazolinediones that have been reported by others, though the mechanism still remains unknown [32, 33].

Preliminary SAR of L2-401 family did not reveal a correlation between inhibition of Alr and reduced microbial growth. Indeed, the two activities likely reside on the opposite sides of the thiadiazolinedione core. Although other possibilities such as cell wall permeability could account for the discordance, it is highly likely that the antimicrobial activity of L2-401 arises from its action on other cellular targets. In support of this notion are previously reported activities of thiadiazolinediones on other non PLP-dependent bacterial enzymes. For instance, thiadiazolinediones have been reported to inhibit the de novo pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as well as ATPase Cagα, a component of the contact-dependent secretion system in Helicobacter pylori [27, 34].

The L2-401 series also inhibited HeLa cell proliferation. Thiadiazolinediones have been reported to have activity against several mammalian cell kinases, such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3β), implicated in certain neurological diseases, diabetes and leukemia [35]. Whether the inhibitory effect of L2-401 on HeLa cell proliferation occurs through inhibition of GSK-3β at present is not known. Nevertheless, this property is undesirable for drug development, and in order for L2-401 to progress to an antibacterial compound of clinical utility significant reduction in inhibition of mammalian cell proliferation is needed.

The central role of Alr in peptidoglycan synthesis has been well established. Development of antibacterials targeting this enzyme, however, has been hampered by the lack of suitable non-substrate-like inhibitors. The identification of the thiadiazolinedione L2-401 by HTS highlights the feasibility of this method to yield such molecules. Although in the case of L2-401, its use as an antibiotic agent in vivo may be limited by chemical liabilities (such as structural instability in blood, potential chemical reactivity with other proteins, and the possibility of non-mechanism-based toxicity), it can nevertheless, serve as a model compound to study the mechanism by which a non-substrate-like inhibitor can block Alr activity, and pave the way for the rational design of more drugable inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ted Voss, Kathy Stone and Jean Kanyo of Yale University for help with MS analysis, and Dr. Ewa Folta-Stogniew and Sweta Sharma for enzyme kinetic analysis. High-throughput screening resources were provided by the NSRB facility (NIAID U54 AI057159) at Harvard Medical School. The authors thank the NSRB staff for their expert advice and technical assistance. This project was supported by a grant (5U01AI082081) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crum NF, Lee RU, Thornton SA, Stine OC, Wallace MR, Barrozo C, Keefer-Norris A, Judd S, Russell KL. Fifteen-year study of the changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Med. 2006;119:943–951. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finks J, Wells E, Dyke TL, Husain N, Plizga L, Heddurshetti R, Wilkins M, Rudrik J, Hageman J, Patel J, Miller C. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Michigan, USA, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:943–945. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.081312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh CT. Enzymes in the D-alanine branch of bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan assembly. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2393–2396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Heijenoort J. Biosynthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan unit. In: Ghuysen J, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial Cell Wall. Amsterdam: Elsevier Medical Press; 1994. pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenni R, Berger-Bachi B. Teichoic acid content in different lineages of Staphylococcus aureus NCTC8325. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s002030050630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidenmaier C, Peschel A. Teichoic acids and related cell-wall glycopolymers in Gram-positive physiology and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhaus F. D-cycloserine and O-carbamyl-D-serine. Heidelbaerg: Springer-Verlag; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhaus FC, Hammes WP. Inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis by analogues and alanine. Pharmacol Ther. 1981;14:265–319. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(81)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MG, Strych U, Krause K, Benedik M, Kohn H. N(2)-substituted D,L-cycloserine derivatives: synthesis and evaluation as alanine racemase inhibitors. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2003;56:160–168. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MG, Strych U, Krause K, Benedik M, Kohn H. Evaluation of Amino-substituted Heterocyclic Derivatives as Alanine Racemase Inhibitors. Medicinal Chemistry Research. 2003;12:130–138. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copie V, Faraci WS, Walsh CT, Griffin RG. Inhibition of alanine racemase by alanine phosphonate: detection of an imine linkage to pyridoxal 5'-phosphate in the enzyme-inhibitor complex by solid-state 15N nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4966–4970. doi: 10.1021/bi00414a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erion MD, Walsh CT. 1-Aminocyclopropanephosphonate: time-dependent inactivation of 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylate deaminase and Bacillus stearothermophilus alanine racemase by slow dissociation behavior. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3417–3425. doi: 10.1021/bi00386a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badet B, Roise D, Walsh CT. Inactivation of the dadB Salmonella typhimurium alanine racemase by D and L isomers of beta-substituted alanines: kinetics, stoichiometry, active site peptide sequencing, and reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5188–5194. doi: 10.1021/bi00317a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toney MD. Reaction specificity in pyridoxal phosphate enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthony KG, Strych U, Yeung KR, Shoen CS, Perez O, Krause KL, Cynamon MH, Aristoff PA, Koski RA. New Classes of Alanine Racemase Inhibitors Identified by High-Throughput Screening Show Antimicrobial Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esaki N, Walsh CT. Biosynthetic alanine racemase of Salmonella typhimurium: purification and characterization of the enzyme encoded by the alr gene. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3261–3267. doi: 10.1021/bi00359a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Approved standards M7-A5: methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 5. Wayne, PA: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plata KB, Rosato RR, Rosato AE. Fate of mutation rate depends on agr locus expression during oxacillin-mediated heterogeneous-homogeneous selection in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3176–3186. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01119-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schenk S, Laddaga RA. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;73:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90596-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novick R. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology. 1967;33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crichlow GV, Lubetsky JB, Leng L, Bucala R, Lolis EJ. Structural and kinetic analyses of macrophage migration inhibitory factor active site interactions. Biochemistry. 2009;48:132–139. doi: 10.1021/bi8014423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian G, Paschetto KA, Gharahdaghi F, Gordon E, Wilkins DE, Luo X, Scott CW. Mechanism of inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase by sulfonamide-containing benzothiazoles: long residence time derived from increased kinetic barrier and not exclusively from thermodynamic potency. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6867–6878. doi: 10.1021/bi200552p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morollo AA, Petsko GA, Ringe D. Structure of a Michaelis complex analogue: propionate binds in the substrate carboxylate site of alanine racemase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3293–3301. doi: 10.1021/bi9822729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcinkeviciene J, Rogers MJ, Kopcho L, Jiang W, Wang K, Murphy DJ, Lippy J, Link S, Chung TD, Hobbs F, et al. Selective inhibition of bacterial dihydroorotate dehydrogenases by thiadiazolidinediones. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halouska S, Chacon O, Fenton RJ, Zinniel DK, Barletta RG, Powers R. Use of NMR metabolomics to analyze the targets of D-cycloserine in mycobacteria: role of D-alanine racemase. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4608–4614. doi: 10.1021/pr0704332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng YQ, Walton JD. A eukaryotic alanine racemase gene involved in cyclic peptide biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4906–4911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann K, Schneider-Scherzer E, Kleinkauf H, Zocher R. Purification and characterization of eucaryotic alanine racemase acting as key enzyme in cyclosporin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12710–12714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uo T, Yoshimura T, Tanaka N, Takegawa K, Esaki N. Functional characterization of alanine racemase from Schizosaccharomyces pombe: a eucaryotic counterpart to bacterial alanine racemase. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2226–2233. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.7.2226-2233.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganapathi RR, Robins RK. 1,2,4-Thiadiazolidine-3.5-dione. USA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heuer L, Wachtler P, Kugler M. Thiazole antiviral agents. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilleringmann M, Pansegrau W, Doyle M, Kaufman S, MacKichan ML, Gianfaldoni C, Ruggiero P, Covacci A. Inhibitors of Helicobacter pylori ATPase Cagalpha block CagA transport and cag virulence. Microbiology. 2006;152:2919–2930. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez A, Alonso M, Castro A, Dorronsoro I, Gelpi JL, Luque FJ, Perez C, Moreno FJ. SAR and 3D-QSAR studies on thiadiazolidinone derivatives: exploration of structural requirements for glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7103–7112. doi: 10.1021/jm040895g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]