Abstract

Purpose

The outcomes of patients with melanoma who have sentinel lymph node (SLN) metastases can be highly variable, which has precluded establishment of consensus regarding treatment of the group. The detection of high-risk patients from this clinical setting may be helpful for determination of both prognosis and management. We report the utility of multimarker reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in patients with melanoma diagnosed with SLN metastases in a phase III, international, multicenter clinical trial.

Patients and Methods

Blood specimens were collected from patients with melanoma (n = 331) who were clinically disease-free after complete lymphadenectomy (CLND) before entering onto a randomized adjuvant melanoma vaccine plus bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) versus BCG placebo trial from 30 melanoma centers (United States and international). Blood was assessed using a verified multimarker RT-qPCR assay (MART-1, MAGE-A3, and GalNAc-T) of melanoma-associated proteins. Cox regression analyses were used to evaluate the prognostic significance of CTC status for disease recurrence and melanoma-specific survival (MSS).

Results

Individual CTC biomarker detection ranged from 13.4% to 17.5%. There was no association of CTC status (zero to one positive biomarkers v two or more positive biomarkers) with known clinical or pathologic prognostic variables. However, two or more positive biomarkers was significantly associated with worse distant metastasis disease-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.13, P = .009) and reduced recurrence-free survival (HR = 1.70, P = .046) and MSS (HR = 1.88, P = .043) in a multivariable analysis.

Conclusion

CTC biomarker status is a prognostic factor for recurrence-free survival, distant metastasis disease-free survival, and MSS after CLND in patients with SLN metastasis. This multimarker RT-qPCR analysis may therefore be useful in discriminating patients who may benefit from aggressive adjuvant therapy or stratifying patients for adjuvant clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

The risk of relapse for patients with melanoma with palpable lymph node (LN) metastasis is high at 5 years1–3; thus systemic adjuvant therapy after surgery for these patients is a rational strategy to improve disease outcome. However, a consensus regarding the management for curatively resected melanoma with nonpalpable regional metastasis such as tumor-positive sentinel lymph node (SLN) has not been obtained. Rates of recurrence, distant metastasis, and death were considerably lower in patients with SLN micrometastasis than in patients with palpable LN regional metastasis.2,3 Nevertheless, up to 40% of patients with SLN metastasis experience melanoma recurrence or melanoma-specific death within 10 years of follow-up. Thus the ability to identify those SLN-positive patients at a high risk of recurrence would mitigate the clinical problem of timely treatment for those who would benefit from available adjuvant therapy or closer monitoring.

Currently the accurate diagnosis of SLN metastasis has been shown to be of significant value in predicting recurrence potential.4–6 However, no blood biomarkers have been shown to be prognostic for recurrence or overall survival (OS) in patients with melanoma with SLN metastasis and verified in a multicenter phase III clinical trial setting. We hypothesized that tumor cells circulating in patients after SLN biopsy plus complete lymphadenectomy (CLND) may be a prognostic factor signifying ongoing subclinical metastasis. Detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the blood of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) patients with stage III melanoma after CLND may be used to stratify patients with high risk of recurrence.

Molecular detection of CTCs has emerged as a promising prognostic and potential predictive biomarker in various malignancies.7–11 Our previous studies demonstrated the need for assessment of multiple CTC biomarkers because of the relatively limited sensitivity of single-biomarker assessment.12 We and other groups have demonstrated that the detection of CTC using multimarker reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is practical and is associated with clinical outcome in patients with melanoma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer.7–9,12–15 The specific RT-qPCR biomarkers used in this study to assess the patients with melanoma are MART-1, MAGE-A3, and GalNAc-T, which were previously described in our studies on phase II trials of patients with AJCC stage III and IV melanoma.13,14 The biomarkers are expressed by melanoma, related to melanoma progression, and do not overlap in function.

In this study, we present the multimarker RT-qPCR analysis of blood specimens from post-CLND clinically disease-free patients with melanoma enrolled onto a prospective phase III international multicenter trial of a postsurgery adjuvant immunotherapy with melanoma cell vaccine (CanVaxin; Cancer Vax, Carlsbad, CA).16,17 Blood specimens were collected on entering onto this phase III clinical trial from patients with stage III melanoma who were randomly assigned into bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) plus placebo versus BCG plus CanVaxin. We report the results of the cohort of patients with positive SLN metastasis.3,18 The study verifies the utility of the CTC biomarker assessment at the time point after CLND surgical treatment and before initiating adjuvant therapy. As such, CTC detection using multimarker RT-qPCR has the potential to help stratify patients for treatment and surveillance strategy. The study demonstrates that CTC can be a predictive blood biomarker for recurrence and overall survival in patients with early stage III melanoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Blood Specimens

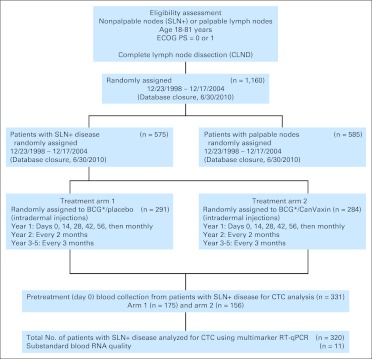

The Malignant Melanoma Active Immunotherapy Trial (MMAIT) AJCC stage III multicenter international randomized trial was conducted at US and non-US melanoma centers from 1998 to 2004 (Appendix Table A1, online only).16,17 The study was closed October 2005, and follow-up data were collected under a separate protocol until June 2010 (Fig 1). Patients 18 to 81 years of age with metastatic cutaneous melanoma who were clinically disease-free after CLND for histologically confirmed LN metastases and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 were eligible for enrollment. The clinical trial and companion CTC assay were approved by the institutional review board at John Wayne Cancer Institute (JWCI)/St. John's Health Center and all participating sites (Appendix). After providing informed consent, 1,160 patients with AJCC stage III melanoma were enrolled. The design of this trial was double-blind and placebo-controlled. After randomization, CanVaxin, an allogeneic whole-melanoma cell vaccine plus BCG (Tice strain; Organon Technika, Durham, NC) or placebo plus BCG was administrated by intradermal injection within 90 days after CLND. BCG was used as an immunologic adjuvant with the first two doses (days 0 and 14) of both CanVaxin and placebo groups. CanVaxin alone or placebo alone (without BCG) was administered on days 28, 42, and 56 and then monthly thereafter during year 1, every 2 months during year 2, and every 3 months during years 3 through 5. Patients' blood samples were obtained for RT-PCR testing at treatment baseline before administration of adjuvant therapy (pretreatment). Among 1,160 patients, 575 patients had SLN metastasis (49.6%), and 585 were patients with palpable regional metastasis (50.4%). Blood samples were collected from 331 of the 575 patients with SLN metastasis and assessed for CTC using multimarker RT-qPCR (Fig 1). Patient blood samples from international sites included in the CTC biomarker study were procured and processed by the international sites using standard operating procedures established in our molecular core laboratory with reagents supplied by JWCI. Approved sites for participating in the CTC biomarker study were trained and monitored in the standard operating procedures for specimen processing, storage, and shipment. The trial study quality assurance was monitored by JWCI clinical trial operations center. The overall clinical trial was monitored by a National Cancer Institute data safety monitoring committee.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. (*) Coadministered on days 0 and 14. BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CTC, circulating tumor cells; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance score; RT-qPCR, reverse-transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

Blood Procurement, RNA Isolation, and Reverse Transcription

Before the start of MMAIT, 9.5 mL of whole blood was drawn using two sodium citrate tubes. Patient specimens received at JWCI were computer coded and entered into a restricted clinical trial database. Blood specimens were immediately processed for the isolation of nucleated cells in blood from RBCs with Purescript RBC Lysis Solution (Gentra Systems, Minneapolois, MN). Total RNA was extracted from purified cells using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). RNA concentration was determined by a spectrophotometer reading at 260/280 nm and Quant-it RiboGreen RNA Quantification Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Blood specimens yielding RNA of insufficient quality and quantity were not included in the study.

One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA as previously described using 200 U of Molony murine leukemia virus reverse-transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), dNTPs, Oligo-d(T) primer (Gene Link, Hawthorne, NY), 20 U of Recombinant RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor, and buffer.

Multimarker qPCR Assay

Multimarker qPCR assay, as previously developed to have optimal sensitivity, specificity, and reliability,19,20 was performed to assess the mRNA expression level of melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1(MART-1), melanoma-antigen gene A3 family (MAGE-A3), and β-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyl transferase (GalNAc-T). MART-1 is a melanoma-related antigen highly expressed by metastatic melanomas (> 85%) and is immunogenic in patients.21,22 MAGE-A3 is a tumor-related gene expressed in melanomas (> 60%), particularly aggressive metastatic disease.23 MAGE-A3 has been shown to be immunogenic and has been targeted in vaccine therapy.24,25 GalNAc-T is a key enzyme factor for gangliosides GM2 and GD2 synthesis in melanomas.26 Previously, we have shown that GM2/GD2 are highly related to melanoma progression and metastasis.27–29 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)23,26,30 was used as a reference control for RNA quality and assay variability.19,20 Primers and hydrolysis probe sequences for each CTC biomarker are the same as previously described.20 qPCR on individual markers was performed in duplicate to determine mRNA expression levels of each gene using the iCycler iQ RealTime Thermocycler Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Los Angeles, CA).20 In brief, PCR amplification was performed with iTaq Fast supermix ROX (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 0.4 μmol/L of each primer, 0.3μmol/L of probe, and 5 μL of cDNA. Samples were amplified with a precycling hold at 95°C (10 minutes), followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (1 minute), annealing at 55°C (1 minute) for GAPDH (59°C for MART-1, 58°C for MAGE-A3, and 62°C for GalNAc-T), and extension at 72°C (1 minute). qPCR assay was performed in a blinded manner without knowledge of patient outcomes. The average threshold (Cq) value of the duplicates was used for analysis. Peripheral-blood lymphocytes from 22 healthy volunteers were tested to determine the cutoff Cq value for each biomarker13: 42 for MART-1, 39 for MAGE-A3, and 40 for GalNAc-T. When the Cq mean for a sample was lower than the cutoff value, the gene expression was considered to be positive. For each assay, biomarker-positive (melanoma cell lines), biomarker-negative (healthy donor lymphocytes), reagent controls, and no template controls were included. A standard curve was generated by using threshold cycles of multiple serial dilutions of specific gene cDNA plasmid templates (10 to 106 copies) to assess PCR efficiency. Any sample yielding Cq of more than 30 for GAPDH was excluded from analysis for poor RNA quality. Data development and analysis were carried out in accordance with the minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines.31

Biostatistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were tabulated and compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for numerical variables. Survival curves were constructed according to the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used for comparison of survival curves. Cox models were constructed to evaluate the prognostic significance of the biomarker status with clinical outcomes while adjusting for clinical factors. Age, sex, ulceration, thickness, number of positive nodes, treatment, and number of positive CTC biomarkers (zero to one positive CTC biomarker v two or more positive CTC biomarkers) were included in the model. All analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The reported P value were considered significant if less than .05. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) guidelines were followed in analysis.32

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Eleven patients were excluded for inadequate RNA quality, leaving 320 patients for multimarker RT-qPCR analysis: 263 patients from 26 US clinics and 57 patients from 4 non-US clinics. Of the 320 patients, all had CLND. Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathologic variables of the patients studied. The female-to-male ratio was 125 to 195, and the median age was 51.1 years (range, 18 to 81 years). Of 320 patients (those who were initially entered onto the study as AJCC stage I/II) with nonclinical detectable regional metastasis, 149 patients were randomly assigned for the BCG plus placebo group, and 171 patients were randomly assigned for the BCG plus CanVaxin group. Although there were more men in the BCG plus CanVaxin group than the BCG plus placebo group (P = .013, χ2 test), there were no significant differences in other established prognostic factors (age, primary site, ulceration, thickness, level of invasion, and number of positive LNs) between the two treatment arms. With median follow-up time of 51.7 months, 134 (42%) suffered disease recurrence, 97 (30%) had distant recurrence, 85 (27%) died, and 81 (25%) died as a result of melanoma.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Prognostic Factors | BCG/Placebo(n = 149) |

BCG/CanVaxin(n = 171) |

Total(n = 320) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 69 | 46.0 | 56 | 33.0 | 125 | 39.0 |

| Male | 80 | 54.0 | 115 | 67.0 | 195 | 61.0 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 50.7 | 51.8 | 51.2 | |||

| SD | 13.8 | 15.1 | 14.5 | |||

| Median | 50.7 | 51.3 | 51.1 | |||

| Range | 18-81 | 20-80 | 18-81 | |||

| Primary site | ||||||

| Extremity | 74 | 49.7 | 77 | 45.0 | 151 | 47.2 |

| Head/neck | 11 | 7.4 | 23 | 13.5 | 34 | 10.6 |

| Trunk | 62 | 41.6 | 68 | 39.8 | 130 | 40.6 |

| Other/unknown | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.6 |

| Thickness, mm | ||||||

| Mean | 2.91 | 3.13 | 3.03 | |||

| SD | 2.08 | 2.77 | 2.47 | |||

| Median | 2.32 | 2.40 | 2.35 | |||

| Range | 0.30-12.0 | 0.30-20.0 | 0.30-20.0 | |||

| ≤ 1.0 | 16 | 10.7 | 26 | 15.2 | 42 | 13.1 |

| 1.01-2.00 | 46 | 30.9 | 47 | 27.5 | 93 | 29.1 |

| 2.01-4.00 | 52 | 34.9 | 59 | 34.5 | 111 | 34.7 |

| > 4.00 | 32 | 21.5 | 35 | 20.5 | 67 | 20.9 |

| Unknown | 3 | 2.0 | 4 | 2.3 | 7 | 2.2 |

| Level of invasion | ||||||

| II | 3 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.6 |

| III | 21 | 14.1 | 31 | 18.1 | 52 | 16.2 |

| IV | 112 | 75.2 | 111 | 64.9 | 223 | 69.7 |

| V | 3 | 2.0 | 13 | 7.6 | 16 | 5.0 |

| Unknown | 10 | 6.7 | 14 | 8.2 | 24 | 7.5 |

| Ulceration | ||||||

| Present | 49 | 32.9 | 52 | 30.4 | 101 | 31.6 |

| Absent | 63 | 42.3 | 84 | 49.1 | 147 | 45.9 |

| Unknown | ||||||

| Positive SLNs | 37 | 24.8 | 35 | 20.5 | 72 | 22.5 |

| 1 | 93 | 62.4 | 107 | 62.6 | 200 | 62.5 |

| 2-4 | 50 | 33.6 | 57 | 33.3 | 107 | 33.4 |

| ≥ 5 | 6 | 4.0 | 7 | 4.1 | 13 | 4.1 |

| No. of CTC biomarkers | ||||||

| 0 | 94 | 63.1 | 118 | 69.0 | 212 | 66.2 |

| 1 | 37 | 24.8 | 39 | 22.8 | 76 | 23.8 |

| 2 | 15 | 10.1 | 14 | 8.2 | 29 | 9.1 |

| 3 | 3 | 2.0 | 0 | 3 | 0.9 | |

NOTE. There were no statistical differences in American Joint Committee on Cancer stage III known prognostic factors except for sex (P = .013) between the two treatment groups.

Abbreviations: BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CTC, circulating tumor cells; SD, standard deviation; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

CTC Biomarker Status

Pretreatment blood specimens were assessed to determine whether CTC detection could have utility as a prediction biomarker assay for disease outcome in post-CLND disease-free patients with AJCC stage III melanoma with SLN metastasis. Detection frequency of each CTC biomarker was as follows: MART-1, 44 (13.8%); MAGE-A3, 43 (13.4%); and GalNAc-T, 56 (17.5%). No significant differences of individual CTC biomarker detection frequency or number of positive CTC biomarkers were observed between the two treatment arms.

The patients (n = 320) were classified into zero to one positive biomarker (n = 288; 90%) and two or more positive biomarkers (n = 32; 10%) groups. There were no significant differences between the zero to one positive biomarker versus two or more positive biomarkers groups with respect to prognostic factors (sex, age, primary site, thickness, ulceration, level of invasion, and number of positive LNs; Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of CTC Biomarker Status With Clinicopathologic Variables

| Prognostic Factor | 0-1 Positive Biomarkers(n = 288) |

≥ 2 Positive Biomarkers(n = 32) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 109 | 37.8 | 16 | 50.0 |

| Male | 179 | 62.2 | 16 | 50.0 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean | 50.7 | 55.8 | ||

| SD | 14.6 | 13.1 | ||

| Median | 50.9 | 56.1 | ||

| Range | 18-81 | 30-80 | ||

| Primary site | ||||

| Extremity | 137 | 47.6 | 14 | 43.8 |

| Head/neck | 29 | 10.1 | 5 | 15.6 |

| Trunk | 117 | 40.6 | 13 | 40.6 |

| Unknown | 5 | 1.7 | 0 | |

| Thickness, mm | ||||

| Mean | 3.05 | 2.90 | ||

| SD | 2.53 | 1.87 | ||

| Median | 2.30 | 2.40 | ||

| Range | 0.30-20.0 | 0.50-8.00 | ||

| ≤ 1.0 | 37 | 12.8 | 5 | 15.6 |

| 1.01-2.00 | 85 | 29.5 | 8 | 25.0 |

| 2.01-4.00 | 100 | 34.7 | 11 | 34.4 |

| > 4.00 | 59 | 20.5 | 8 | 25.0 |

| Unknown | 7 | 2.4 | 0 | |

| Level of invasion | ||||

| II | 5 | 1.7 | 0 | |

| III | 48 | 16.7 | 4 | 12.5 |

| IV | 201 | 69.8 | 22 | 68.7 |

| V | 13 | 4.5 | 3 | 9.4 |

| Unknown | 21 | 7.3 | 3 | 9.4 |

| Positive SLNs | ||||

| 1 | 182 | 63.2 | 18 | 56.3 |

| 2-4 | 94 | 32.6 | 13 | 40.6 |

| ≥ 5 | 12 | 4.2 | 1 | 3.1 |

| Ulceration | ||||

| Present | 91 | 31.6 | 10 | 31.3 |

| Absent | 130 | 45.1 | 17 | 53.1 |

| Unknown | 67 | 23.3 | 5 | 15.6 |

NOTE. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for all variables.

Abbreviations: CTC, circulating tumor cells; SD, standard deviation; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

Disease Outcome Analysis

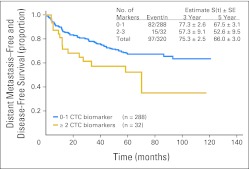

Pretreatment blood specimens were then assessed to determine if CTC detection could have clinical utility as a prediction biomarker for disease outcome in clinically disease-free patients with melanoma. The distant metastasis disease-free survival (DM-DFS) rates of all patients at 3 and 5 years were 75.3%, and 66.0%, respectively. No individual CTC biomarker (MART-1, MAGEA3, or GalNAc-T) was significantly associated with distant recurrence at pretreatment (data not shown). With median follow-up of 51.7 months, 15 (47%) of 32 patients with two or more positive CTC biomarkers in their pretreatment blood specimen experienced distant recurrence, whereas 82 (28%) of 288 patients with zero to one positive CTC biomarker experienced distant relapse. Patients whose blood had zero to one positive biomarker had significantly higher DM-DFS (3 years, 77.3%; 5 years, 67.5%) than those with two or more positive CTC biomarkers (3 years, 57.3%; 5 years, 52.6%; P = .025, log-rank test; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.86, P = .027, Wald test; Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Distant metastasis–free and disease-free survival curves for patients with circulating tumor cell (CTC) biomarker detection. P = .025 (log-rank test).

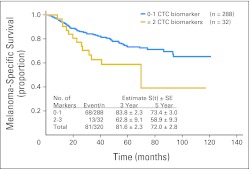

The melanoma-specific survival (MSS) rates of all patients at 3 and 5 years were 81.6%, and 72.0%, respectively. No single CTC biomarker was significantly associated with MSS. Thirteen (41%) of 32 patients with two or more positive biomarkers died as a result of disease, whereas 68 (24%) of 288 patients with zero to one positive biomarker died as a result of disease during follow-up. Patients with zero to one positive biomarker had significantly higher MSS (3 years, 83.8%; 5 years, 73.4%) than patients with two or more positive biomarkers (3 years, 62.8%; 5 years, 58.9%; P = .031, log-rank test; HR = 1.90, P = .034, Wald test; Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Melanoma-specific survival curves for patients with circulating tumor cell (CTC) biomarker detection. P = .031(log-rank test).

In multiple Cox regression analyses, age at randomization, primary tumor thickness, ulceration, the number of positive LNs, and two or more positive CTC biomarkers were significant prognostic factors for recurrence-free survival (RFS), MSS, and DM-DFS (Table 3). Treatment (CanVaxin v placebo) was not significantly correlated with RFS, MSS, or DM-DFS. Having two or more positive CTC biomarkers was a significant prognostic factor for RFS (HR = 1.70, 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.87, P = .046), MSS (HR = 1.88, 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.47, P = .043), and DM-DFS (HR = 2.13, 95% CI, 1.20 to 3.76, P = .009).

Table 3.

Cox Model Analysis

| Prognostic Factor | Distant Metastasis–Free Disease-Free Survival* |

Melanoma-Specific Survival† |

Recurrence-Free Survival‡ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| CTC biomarkers, 2-3 v 0-1 | 2.13 | 1.20 to 3.76 | .0093 | 1.88 | 1.02 to 3.47 | .0430 | 1.70 | 1.01 to 2.87 | .0462 |

| Sex, male v female | 1.42 | 0.90 to 2.25 | .1351 | 1.85 | 1.09 to 3.14 | .0222 | 1.30 | 0.88 to 1.92 | .1854 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.04 | .0004 | 1.04 | 1.02 to 1.06 | < .001 | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | < .001 |

| Breslow, mm | |||||||||

| ≤ 1.00 | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference | |||

| 1.01-2.00 | 2.44 | 0.98 to 6.10 | .0568 | 3.22 | 1.07 to 9.68 | .0376 | 2.28 | 1.07 to 4.86 | .0324 |

| 2.01-4.00 | 1.96 | 0.81 to 4.74 | .1329 | 3.13 | 1.09 to 8.98 | .0342 | 2.19 | 1.06 to 4.51 | .0343 |

| > 4.00 | 3.10 | 1.27 to 7.61 | .0133 | 4.68 | 1.60 to 13.7 | .0049 | 3.08 | 1.46 to 6.50 | .0031 |

| Ulcerations | |||||||||

| Not present | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference | |||||

| Present | 2.58 | 1.56 to 4.27 | .0002 | 2.05 | 1.21 to 3.49 | .0080 | 2.57 | 1.67 to 3.97 | < .001 |

| Unknown | 1.84 | 1.03 to 3.31 | .0404 | 1.24 | 0.64 to 2.41 | .5212 | 2.31 | 1.43 to 3.73 | .0006 |

| No. of positive LNs | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference | |||

| 2-4 | 1.91 | 1.22 to 2.97 | .0044 | 1.83 | 1.13 to 2.97 | .0143 | 1.93 | 1.32 to 2.81 | .0006 |

| ≥ 5 | 4.28 | 2.01 to 9.15 | .0002 | 4.54 | 2.02 to 10.2 | .0003 | 2.80 | 1.35 to 5.80 | .0056 |

| Treatment CanVaxin v placebo (BCG) | 1.37 | 0.90 to 2.09 | .1430 | 1.38 | 0.87 to 2.20 | .1685 | 1.42 | 0.99 to 2.02 | .0574 |

Abbreviations: BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CTC, circulating tumor cells; LNs, lymph nodes.

Only distant metastasis and death owing to melanoma were counted as events; all other recurrences/deaths owing to nonmelanoma causes were counted as censored.

Death owing to melanoma was counted as an event; death resulting from nonmelanoma causes was counted as censored.

Event: the first recurrence (any type).

DISCUSSION

Currently, high-dose interferon alfa (IFN-α) and pegylated IFN-α-2b are the only approved adjuvant therapy for patients with stage III melanoma based on recent clinical trials, but no regimen has emerged as a globally accepted standard.33 Pegylated IFN-α-2b was recently approved based on the randomized phase III trial (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 18991), which has shown the treatment benefit of pegylated IFN-α-2b on RFS and DM-DFS. Of significance to our study, the benefit of IFN-α-2b was only seen in patients with microscopic nodal involvement (SLN metastasis), which is also the patient population analyzed in this study.34 It is likely that newly approved systemic treatments in stage III disease will come into assessment in the adjuvant setting. With the recent advancement in melanoma therapeutics, there will no doubt be new effective agents for stage III patients in the horizon. Indeed, the recently approved anti-CTLA-4 antibody is the subject of two ongoing randomized trials in the adjuvant setting.35–39 With these new therapeutic agents, effective stage III patient adjuvant therapies will likely emerge in the near future.40 Given that all of these therapies have potential toxic adverse effects and are accompanied by considerable cost, the important clinical problem still remains for early stage III patients: who should be treated? A blood test to detect the presence of persistent/subclinical metastatic disease and predict adverse clinical outcomes should be useful in discriminating those patients who will benefit from additional treatment.

We evaluated a possible association of pretreatment CTC detection by multimarker RT-qPCR with clinical outcome in post-CLND disease-free patients with melanoma with nonpalpable regional metastasis. In this study, we demonstrated that two or more CTC biomarkers were significantly associated with DM-DFS and MSS in this clinical setting. The results strengthen the evidence that the use of multiple biomarkers can help overcome challenges posed by melanoma cell heterogeneity and compensate for the sensitivity and specificity deficits of single CTC biomarker.12,41 Furthermore, we demonstrated that CTC detected after locoregional surgical treatment and before adjuvant therapy is effective in predicting RFS, DM-DFS, and MSS. It should be noted that CTCs were detected in some patients whose disease has not yet recurred at the time of this analysis. Not all CTCs will result in clinically evident metastasis9,42; also, CTCs may develop into dormant micrometastasis or may be subject to host immune responses that can potentially prevent CTCs from successfully establishing metastasis.22,24,27,43 The metastatic efficiency and the amount of time it takes for CTCs to develop into clinically evident disease can be influenced by many host and tumor factors.

Diagnostic tumor biomarkers to characterize early-stage tumor aggressiveness or metastatic potential would improve treatment decision making and help implement stratification strategies. CTC can be used postsurgery to further stratify patients for aggressive treatment. As we have previously demonstrated, CTC detection can also be a powerful tool in monitoring patients during neoadjuvant biochemotherapy.13 This is the first study to our knowledge to confirm the utility of blood CTC mRNA biomarkers in the setting of an international, prospective clinical trial.

In the current study, we selected three informative biomarkers (MART1, MAGE-A3, and GalNAc-T), which were previously used to detect both CTCs in blood and upstage hematoxylin and eosin/immunohistochemistry-negative SLNs in patients with melanoma.13,18,20 The detection of these melanoma-associated molecular biomarkers has been demonstrated in SLNs and significantly related to disease outcome in long-term follow-up.18,23 The utility of these molecular biomarkers in SLN upstaging and CTC detection supports the value of the selected biomarkers in prediction of disease outcome in patients with early-stage melanoma. We demonstrated that CTC biomarker status was a significant prognostic factor for MSS in patients with SLN metastasis and that multimarker RT-qPCR assay in this clinical setting remains a significant predictor of clinical outcome in a multiple regression model accounting for common clinical prognostic factors, with the exception of mitotic rate and SLN microscopic tumor burden, which were not considered as standard clinical prognostic factors at the time of the trial but may potentially influence the findings of this study. Given these significant results, CTC biomarker status may be useful in stratifying high-relapse-risk patients for adjuvant therapy.

Currently, highly sensitive assays have been developed and proven useful for the detection of CTCs in blood, such as the use of immunomagnetic bead separation for CTC enrichment by cytokeratin-specific antibody capture.44,45 We have reported a similar tumor cell enrichment technique in melanoma and verified the specific CTC biomarkers are present.(46) However, the multimarker RT-qPCR CTC assay is logistically more practical compared with antibody capture of cells, for which more elaborate laboratory procedures have to be implemented. With quality failure rate at only 3% (11 of 331), the multimarker RT-qPCR CTC assay demonstrated robustness in the clinical setting of this international multicenter study. The multimarker RT-qPCR CTC assay detects expression of multiple melanoma-related genes, suggesting that these CTCs are potentially functional. We have proven by bead capturing of CTCs that these genes are expressed by melanoma cells.(46) In the current clinical environment, in which overdiagnosis is a substantial concern in the field of oncology,(47) the correlation of CTC biomarkers with disease outcome in multiple phase II/III clinical trials in our different studies13,14 should provide a new treatment strategy based on a reliable and robust CTC biomarker assay.

In conclusion, we have shown that the multimarker RT-qPCR assessment of CTCs is useful in prospectively collected post-CLND blood specimens in early-stage metastasis. Together, our finding of correlation between CTC biomarker status and clinical outcome corroborate our previous studies demonstrating the support of the utility of CTC assessment. The study identifies high-risk patients immediately after CLND follow-up. Future validation as a clinical tool in a multicenter clinical setting for Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) and US Food and Drug Administration approval is warranted. CTC assessment may be useful for detecting high-risk SLN-positive patients for aggressive adjuvant therapy.

Appendix

Table A1.

Malignant Melanoma Active Immunotherapy Trial Participating Sites (n = 30)

| Organization Name | Principal Investigator |

|---|---|

| Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori-Napoli, Napoli, Italy | Nicola Mozzillo, MD |

| Sydney Melanoma Unit, Sydney, Australia | John Thompson, MD |

| Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN | Mark Kelley, MD |

| John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica, CA | Donald Morton, MD |

| Indiana University Medical Center/Wagner & Associates, Indianapolis, IN | Jeff Wagner, MD |

| University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA | Lynn Schuchter, MD |

| The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH | Michael Walker, MD |

| Arizona Cancer Center, Scottsdale, AZ | Evan Hersh, MD |

| MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX | Jeffrey Lee, MD |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC | David Ollila, MD |

| University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, TX | James Huth, MD |

| University of California at San Francisco/Mt Zion Cancer Center, San Francisco, CA | Mohammed Kashani-Sabet, MD |

| Lakeland Regional Cancer Center, Lakeland, FL | Douglas Reintgen, MD |

| University of Louisville, Louisville, KY | Kelly McMasters, MD |

| St Louis University Health Sciences Center, St Louis, MO | John Richart, MD |

| St George's Hospital Medical School/Harley Street Clinic, London, United Kingdom | Angus Dalgleish, MD |

| Northwest Medical Specialties, Tacoma, WA | Frank Senecal, MD |

| University of Missouri, Columbia, MO | Clay Anderson, MD |

| Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY | William Kraybill, MD |

| Medical College of Virginia, Richmond, VA | Harry Bear, MD |

| Spectrum Health–Downtown Campus, Grand Rapids, MI | Marianne Lange, MD |

| The Christ Hospital, Cincinnati, OH | Philip Leming, MD |

| H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL | Ronald DeConti, MD |

| Cancer Care Center of Southern Indiana, Bloomington, IN | Karuna Koneru, MD |

| University of Florida–Shand's Hospital, Gainesville, FL | Scott Schell, MD, PhD, FACS |

| St Luke's Hospital Cancer Center, Bethlehem, PA | Lee Riley, MD |

| Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, CA | Robert Barone, MD |

| Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA | Marie-France Demierre, MD |

| Brown University Oncology Group–Roger Williams Hospital, Providence, RI | Harold Wanebo, MD |

| Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada | Michael Smylie, MD. |

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the Malignant Melanoma Active Immunotherapy Trial III Trial Group.

Supported by the Dr Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, the Leslie and Susan Gonda (Goldschmied) Foundation (Los Angeles, CA), the Ruth and Martin H. Weil Fund (Los Angeles, CA), and Grant No. P01 CA012582 from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00052130.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Dave S.B. Hoon, NANT Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sojun Hoshimoto, Donald L. Morton, Dave S.B. Hoon

Financial support: Dave S.B. Hoon

Administrative support: Christine Kuo

Provision of study materials or patients: Kelly Chong, Donald L. Morton

Collection and assembly of data: Sojun Hoshimoto, Tatsushi Shingai, Christine Kuo

Data analysis and interpretation: Sojun Hoshimoto, Donald L. Morton, Mark B. Faries, Kelly Chong, David Elashoff, He-Jing Wang, Robert M. Elashoff

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Moschos SJ, Edington HD, Land SR, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of regional stage IIIB melanoma with high-dose interferon alfa-2b induces objective tumor regression in association with modulation of tumor infiltrating host cellular immune responses. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3164–3171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors among 2,313 patients with stage III melanoma: Comparison of nodal micrometastases versus macrometastases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2452–2459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, Hoon DS, Cochran AJ, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: Therapeutic utility and implications of nodal microanatomy and molecular staging for improving the accuracy of detection of nodal micrometastases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086543.45557.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gershenwald JE, Ross MI. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1738–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1002967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White RL, Jr, Ayers GD, Stell VH, et al. Factors predictive of the status of sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma patients from a large multicenter database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3593–35600. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1826-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyanagi K, Bilchik AJ, Saha S, et al. Prognostic relevance of occult nodal micrometastases and circulating tumor cells in colorectal cancer in a prospective multicenter trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7391–7396. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT, et al. Circulating tumor cells: A novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1420–1430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH, Brandt B. Detection, clinical relevance and specific biological properties of disseminating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrc2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danila DC, Fleisher M, Scher HI. Circulating tumor cells as biomarkers in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3903–3912. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scher HI, Jia X, de Bono JS, et al. Circulating tumour cells as prognostic markers in progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: A reanalysis of IMMC38 trial data. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:233–239. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70340-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoon DS, Bostick P, Kuo C, et al. Molecular markers in blood as surrogate prognostic indicators of melanoma recurrence. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2253–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koyanagi K, O'Day SJ, Gonzalez R, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating melanoma cells during neoadjuvant biochemotherapy for stage III melanoma: Outcome prediction in a multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8057–8064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyanagi K, O'Day SJ, Boasberg P, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor cells predicts outcome of induction biochemotherapy plus maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2402–2408. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa T, Martinez SR, Goto Y, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in early-stage breast cancer metastasis to axillary lymph nodes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4105–4110. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton D, Mozzillo N, Thompson JF, et al. An international, randomized, phase III trial of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) plus allogeneic melanoma vaccine (MCV) or placebo after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional or distant sites. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl 18):474s. abstr 8508. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morton D, Stern S, Elashoff R. Surgical resection for melanoma metastatic to distant sites. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(suppl 1):S21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholl MB, Elashoff D, Takeuchi H, et al. Molecular upstaging based on paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes: Ten-year follow-up confirms prognostic utility in melanoma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;253:116–122. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fca894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshimoto S, Faries MB, Morton DL, et al. Assessment of prognostic circulating tumor cells in a phase III trial of adjuvant immunotherapy after complete resection of stage IV melanoma. Ann Surg. 2012;255:357–362. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182380f56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyanagi K, Kuo C, Nakagawa T, et al. Multimarker quantitative real-time PCR detection of circulating melanoma cells in peripheral blood: Relation to disease stage in melanoma patients. Clin Chem. 2005;51:981–988. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.045096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakami Y, Robbins PF, Wang RF, et al. The use of melanosomal proteins in the immunotherapy of melanoma. J Immunother. 1998;21:237–246. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein O, Ebert LM, Nicholaou T, et al. Melan-A-specific cytotoxic T cells are associated with tumor regression and autoimmunity following treatment with anti-CTLA-4. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2507–2513. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeuchi H, Morton DL, Kuo C, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular upstaging of paraffin-embedded sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2671–2680. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peled N, Oton AB, Hirsch FR, et al. MAGE A3 antigen-specific cancer immunotherapeutic. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:19–25. doi: 10.2217/1750743X.1.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontana R, Bregni M, Cipponi A, et al. Peripheral blood lymphocytes genetically modified to express the self/tumor antigen MAGE-A3 induce antitumor immune responses in cancer patients. Blood. 2009;113:1651–1660. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo CT, Bostick PJ, Irie RF, et al. Assessment of messenger RNA of beta 1–>4-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase as a molecular marker for metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:411–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi T, Johnson TD, Nishinaka Y, et al. IgM anti-ganglioside antibodies induced by melanoma cell vaccine correlate with survival of melanoma patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:205–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuchida T, Saxton RE, Irie RF. Gangliosides of human melanoma: GM2 and tumorigenicity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:55–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/78.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuchida T, Saxton RE, Morton DL, et al. Gangliosides of human melanoma. Cancer. 1989;63:1166–1174. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890315)63:6<1166::aid-cncr2820630621>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyashiro I, Kuo C, Huynh K, et al. Molecular strategy for detecting metastatic cancers with use of multiple tumor-specific MAGE-A genes. Clin Chem. 2001;47:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9067–9072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkwood JM, Manola J, Ibrahim J, et al. A pooled analysis of eastern cooperative oncology group and intergroup trials of adjuvant high-dose interferon for melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1670–1677. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus observation alone in resected stage III melanoma: Final results of EORTC 18991, a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:117–126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cameron F, Whiteside G, Perry C. Ipilimumab: First global approval. Drugs. 2011;71:1093–1104. doi: 10.2165/11594010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239–1246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eggermont AM, Gore M. Randomized adjuvant therapy trials in melanoma: Surgical and systemic. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:509–515. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mocellin S, Hoon D, Ambrosi A, et al. The prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in patients with melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4605–4613. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murali R, Desilva C, Thompson JF, et al. Factors predicting recurrence and survival in sentinel lymph node-positive melanoma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1155–1164. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318214beba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goss PE, Chambers AF. Does tumour dormancy offer a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:871–877. doi: 10.1038/nrc2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:781–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Müller V, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: A validation study of the CellSearch system. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:920–928. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitago M, Koyanagi K, Nakamura T, et al. mRNA expression and BRAF mutation in circulating melanoma cells isolated from peripheral blood with high molecular weight melanoma-associated antigen-specific monoclonal antibody beads. Clin Chem. 2009;55:757–764. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welch HG, Black WC, et al. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]