Abstract

The repeated use of signalling pathways is a common phenomenon but little is known about how they become co-opted in different contexts. Here we examined this issue by analysing the activation of Drosophila Torso receptor in embryogenesis and in pupariation. While its putative ligand differs in each case, we show that Torso-like, but not other proteins required for Torso activation in embryogenesis, is also required for Torso activation in pupariation. In addition, we demonstrate that distinct enhancers control torso-like expression in both scenarios. We conclude that repeated Torso activation is linked to a duplication and differential expression of a ligand-encoding gene, the acquisition of distinct enhancers in the torso-like promoter and the recruitment of proteins independently required for embryogenesis. A combination of these mechanisms is likely to allow the repeated activation of a single receptor in different contexts.

The Torso (Tor) pathway is responsible for the specification of the most anterior and posterior regions of the Drosophila embryo. The Tor receptor itself is present all around the membrane of the early embryo but is activated only at its poles by a mechanism thought to involve the cleavage of its putative ligand, the Trunk (Trk) protein. Trk, which is expressed in the germ line, appears to be synthesised by the early embryo and secreted into the perivitelline space between the embryo membrane and the vitelline membrane, the latter a component of the eggshell that covers the developing embryo. There, in the perivitelline space, Trk is thought to be specifically cleaved at the poles by an unknown mechanism that is dependent on the torso-like (tsl) gene, which encodes a product anchored at the two poles of the vitelline membrane. Tsl is the only known component of the Tor pathway that is locally restricted and its expression domain is precisely what is responsible for the spatially restricted activation of the Tor receptor. However, Tsl is not synthesised in the early embryo, where the Tor protein is produced and accumulates at the membrane. Conversely, Tsl is synthesised by a subset of the somatic cells surrounding the oocyte that are responsible for eggshell production. This process is elaborate and a group of genes that are required for eggshell assembly are also responsible for anchoring Tsl on the vitelline membrane surrounding the embryo (e.g. fs(1)Nasrat (fs(1)N), fs(1)polehole (fs(1)ph) and closca (clos)) (for revisions on eggshell morphogenesis and on Tor signalling in embryonic pattern see1 and2, respectively).

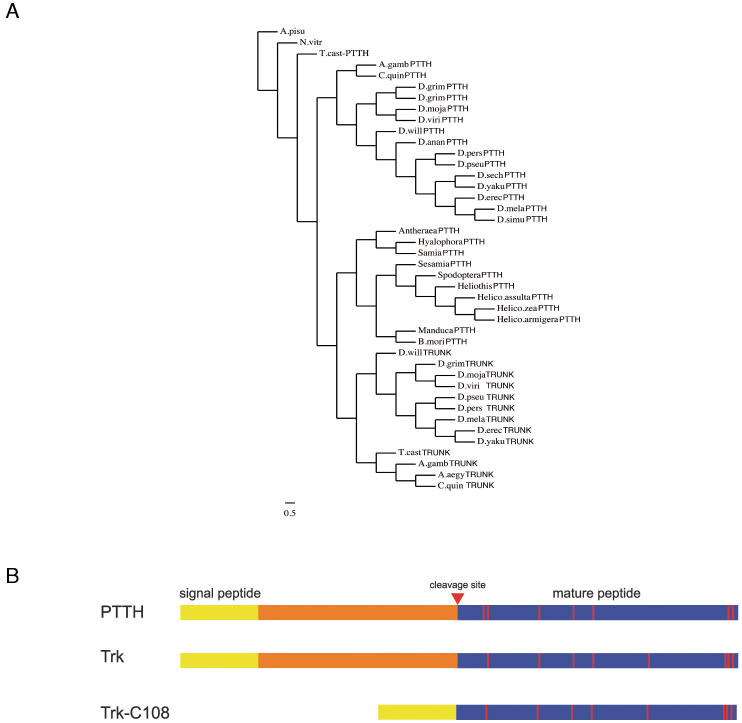

Recently the Tor signalling also has been found to be responsible for the production of the ecdysone peak that triggers the larva to pupa transition; as a result, pupariation is delayed in mutants for the Tor pathway3. For this function, the Tor receptor accumulates in the prothoracic gland3 and is activated by a distinct putative ligand, the Prothoracicotropic hormone (Ptth), which is delivered to the prothoracic gland by two pairs of neurons that innervate the gland4. Thus, the scenario is that of activation of a single receptor at two sites by two different ligands. These two putative ligands are similar at the sequence level -Trk and Ptth form a separate cluster among the cysteine-knot proteins and Ptth is the closest paralog of Trk- and ectopic ptth expression in the germ line partially rescues the lack of trk activity3 and Fig. 1A,B. Here we further analyse Tor activation in the prothoracic gland and compare it to Tor activation in the embryo in order to identify common and specific elements. We discuss the implications of our results for the dual activation of the signalling pathway.

Figure 1. Torso ligands are structurally and phylogenetically related.

(A) Phylogenetic tree for Ptth and Trk from different insect species generated with the SATCHMO software38 and the Drawgram viewer (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/one_task.cgi?task_type=drawgram). (B) Diagram of Drosophila Ptth, Trk, and TrkC108. Processing of Ptth and Trk is believed to release the mature C-terminal peptides (blue boxes). For details on TrkC108 see7. Red vertical lines indicate cysteines.

Results

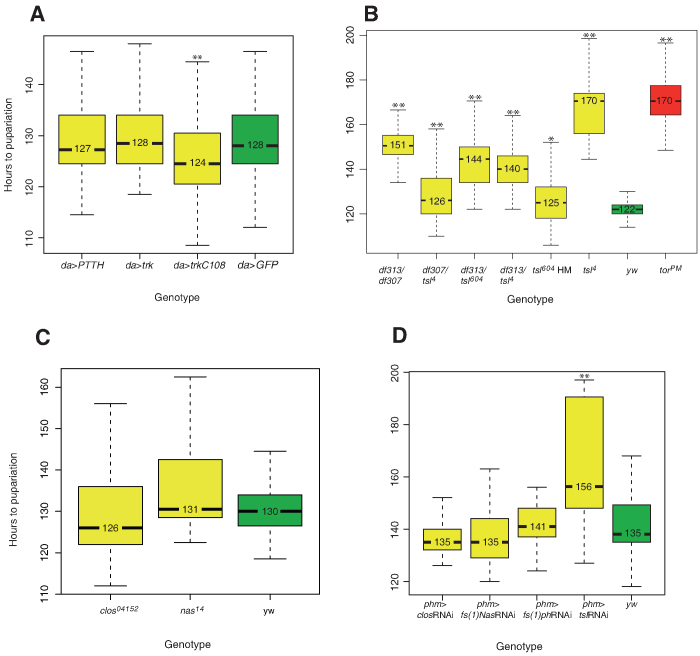

First, to assess whether Trk can also trigger Tor activation in the prothoracic gland if appropriately expressed, we took advantage of the GAL4/UAS system5 to induce general trk expression (see methods). For this purpose, we used the same driver as previously used to assess whether general expression of ptth advances the time of pupariation4. In this experiment we obtained similar results with trk and ptth, which in our hands did not produce a substantial effect (Fig. 2A). Of note, time of pupariation depends on many extrinsic conditions (temperature, food quality, etc.) as well as the genetic background. In order to be sure about the significance of the differences we have always referred our measurements to internal controls performed in parallel and in the same conditions as the actual experiment. Thus, while showing an internal consistence it is nevertheless difficult to compare the data from different set of experiments, which does not allow making a direct comparison between results obtained in different set of experiments in the same or different laboratories. The finding that general expression of trk did not produce a substantial effect on pupariation is in agreement with the observation that extra copies of trk do not increase Tor signalling in the embryo6 and other observations, suggesting that the processing and not the overall amount of the Trk protein is the limiting factor for Tor activation2,7. Consistently, we found that general expression of TrkC108 (Fig. 1B), a truncated version of the protein that acts as an active form of Trk in embryonic patterning7, has a mild but statistically significant effect in advancing the time of pupariation (Fig. 2A). This result is consistent with the observation that even expression of a constitutive form of the Tor receptor produces a rather minor advance in the time of pupariation3. Thus, the Tor receptor can be activated in both settings by either ligand, provided they are appropriately expressed and activated. While it has not been possible to generate a stable active form of Ptth3, these results together with the partial rescue of the trk mutants by germ-line expression of ptth3 suggest that a full-length Ptth is also likely to be cleaved.

Figure 2. Analysis of pupariation time.

(A) Overexpression of ptth and full-length trk does not significantly advance pupariation as compared to GFP overexpression, while overexpression of a cleaved form of trk (trkC108) slightly but significantly advances pupariation (individuals examined: da>trk,110; da>trkc108,58; da>Ptth,72; da>GFP,86). (B) All tsl mutant combinations analysed show significant developmental delays when compared to a yw control (individuals examined df313/df307: 96; tsl313/tsl604: 121; df307/tsl4: 97; df313/tsl4: 71; tsl604: 90; tsl4: 35; torPM: 75; yw: 164). (C) Conversely, fs(1)N and clos mutants do not show any significant delay (individuals examined: fs(1)N14: 116; clos04152: 117; yw: 138). (D) Prothoracic gland knockdown of fs(1)N, clos and tsl produce the same outcome as that of their corresponding mutants; knock-down of fs(1)ph also behaves as those for fs(1)N and clos (individuals examined: phm>tslRNAi,22; phm>fs(1)phRNAi: 30; phm>fs(1)NRNAi: 41; phm>closRNAi: 32; yw: 56). Boxplots were used to represent data: black lines represent medians, colour boxes represent the interquartile range and small bars at the ends of dotted lines represent the upper and the lower values. * is used to indicate a p-value <0.05 and ** is used to indicate a p-value <0.01.

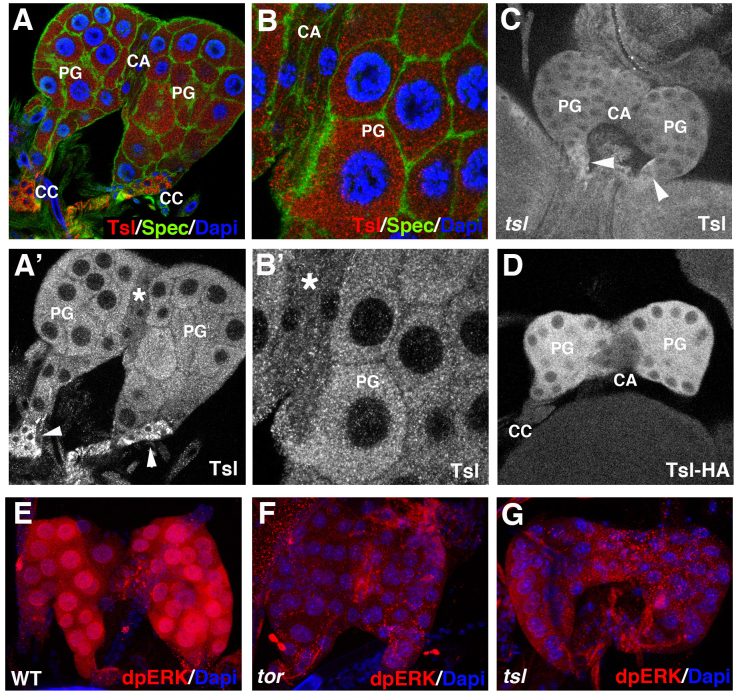

Since Tsl is required to shift Trk to an active form in the germ-line, we addressed whether Tsl could have a similar role in the prothoracic gland. First we analysed if Tsl accumulates in the prothoracic gland. Expression was detected by the use of an anti-Tsl antibody, which shows Tsl accumulation in the prothoracic gland (Fig. 3A,B). Specificity of the prothoracic gland signal is confirmed by its absence in the transheterozygote combination for two deficiencies uncovering the tsl gene (Fig. 3C). Curiously, antibody staining also showed staining in the corpora cardiaca, which appears to be non-specific as it is also observed in the above-mentioned null condition for tsl. (Fig. 3A',C). These results were confirmed by the use of a tsl-HA tag form expressed under the control of the tsl promoter8, which we found expressed in the prothoracic gland at least from the second larval instar (data not shown), but neither in the corpora cardiaca nor in the corpus allatum (Fig 3D). Finally, the anti-Tsl antibody also specifically detects Tsl accumulation in the ovarian cells known to express tsl (data not shown). Tsl accumulation in the prothoracic gland prompted us to analyse whether tsl mutants present a delay in pupariation. Since pupariation time can be greatly affected by the genetic background or even by second site mutations in the chromosomes bearing the particular tsl alleles, we analysed several tsl mutant combinations. In spite of some variation between tsl mutants, larvae presented a significant delay in pupariation (Fig. 2B). Finally, to study whether tsl function is specifically required in the prothoracic gland, we inactivated the function of this gene by an RNAi construct under the control of a phm-gal4 driver9. Under these conditions, pupariation was delayed in a similar way (Fig. 2D).

Figure 3. tsl expression and patterns of dpERK in the prothoracic gland.

(A,B) A ring gland from a 3rd instar larva stained with anti-Tsl (red) and anti-Spectrin (green) antibodies and DAPI (blue). (A',B') Same pictures showing only Tsl accumulation; antibody signal is detected at the prothoracic gland (PG) and in the corpora cardiaca (CC) (arrowheads) but not in the corpus allatum (CA) (asterisk). (C) Specificity of the signal at the PG is shown by its absence in 3rd instar larvae mutant for a tsl null combination (Df(3R)cakiX-313/CASKX-307); conversely, signal at the CC appears to be unspecific because it is also detected in the tsl null combination (arrowheads). (D) A ring gland from a 3rd instar larva bearing a tsl-HA construct stained with an anti-HA antibody; signal is detected in the PG but not in the CA nor in the CC. All images correspond to single stacks. (E–G) Anti-dpERK staining (red) at the PG from wild type (E), torXR (F) and tsl4 (G) 3rd instar larvae; dpERK is detected only in the wild type.

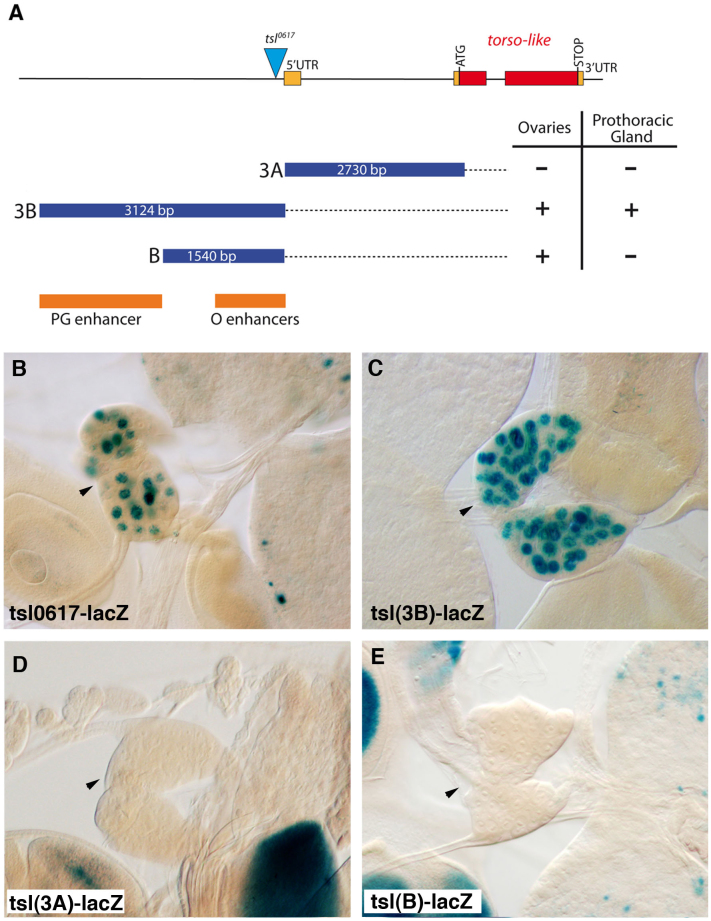

We next addressed whether Tsl activity in the prothoracic gland is indeed required for Tor activation. We monitored MAPK/ERK diphosphorylation as a readout of Tor activity. In the wild-type, dpERK strongly accumulated in the cells of the prothoracic gland (Fig. 3E) in a Tor-dependent manner, as dpERK was barely detected in the prothoracic gland of tor mutants (Fig. 3F). Similar results were obtained for the prothoracic gland in tsl mutant larvae (Fig. 3G). All together, these data indicate that tsl is specifically expressed in the prothoracic gland and that its activity is required for Tor activation. A previous analysis of the tsl promoter identified two enhancer regions responsible for its expression in distinct groups of somatic follicle cells in the ovary10. Using the same kind of reporter construct analysis, we revealed that a different region of the tsl promoter drives its expression in the prothoracic gland, thus indicating the presence of a separate prothoracic gland enhancer (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Distinct enhancers regulate tsl expression in the prothoracic gland and in the ovarian follicular epithelium.

(A) The tsl gene and fragments tested for enhancer activity10. Red and orange rectangles are translated and untranslated exons respectively. The triangle is the P element in tsl0617. Blue rectangles are the fragments in the in vivo enhancer assay. Dark orange rectangles show the identified enhancers, PG for the prothoracic gland and O for the ovaries (for expression in ovaries see10). (B) Expression of the P-enhancer trap tsl0617 is detected in the PG (arrowhead). (C–E) While tsl(3B) drives lacZ expression in the PG, tsl(3A) and tsl(B) do not (arrowheads).

Another set of genes is required for embryonic Tor activation, upstream of Trk. In particular, the products of the genes fs(1)N, fs(1)ph and clos are needed for the proper anchoring/stabilisation of the Tsl protein on the vitelline membrane, which has been held responsible for their involvement in Tor activation8,11,12. In addition, Stevens and collaborators11 have postulated a further requirement of the fs(1)N and fs(1)ph gene products in order for Tsl to exert its function, a not yet identified requirement not due simply to the amount of Tsl protein on the vitelline membrane. This proposal prompted us to analyse whether these genes are similarly required for Tor activation in the prothoracic gland. However, we did not detect any specific expression of Ha-tagged rescuing constructs for fs(1)N, fs(1)ph or clos in the prothoracic gland, any specific signal by in situ hybridization or any specific staining with a Clos antibody, the only one available for one of these three gene products (data not shown). Accordingly, we did not detect any consistent pupariation delay in either the fs(1)N or clos mutants (Fig. 2C) or upon expression of the fs(1)N, fs(1)ph or clos RNAi constructs under the control of the phmgal4 driver (Fig. 2D).

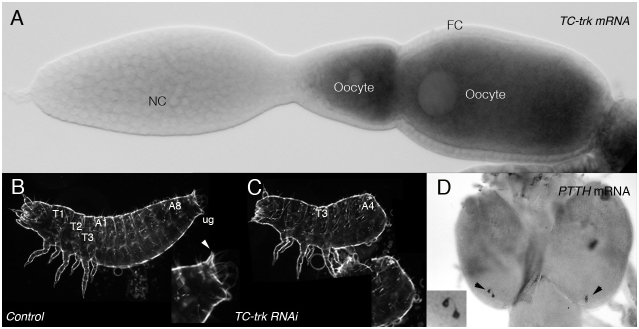

The structural similarity between Ptth and Trk suggest a possible shared origin probably due to a duplication of an ancestral gene. To address this question we sought those genes in different insects. Orthologues for both trk and ptth have been identified in Tribolium castaneum (Tc-trk and Tc-ptth) (13,14 and our own results). Conversely, we have found only one ortholog in Nasonia, a member of the Hymenopthera, which are thought to be the most basal group of the holometabolous insects and in the aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, a hemimetabolous insect. This finding indicates that the presumed duplication at the origin of the two putative ligands occurred at the base of the holometabolous insects (Fig. 1A). More interestingly, we have found that the Tribolium genes display the same differential regional expression pattern as their Drosophila homologues: Tc-trk is expressed in the oocyte and Tc-ppth in some neurons in the brain (Fig. 5A,D). Accordingly, injection of Tc-trk RNAi, but not Tc-ptth RNAi, in the abdomen of Tribolium females led to the production of larvae offspring with a terminal phenotype (Fig. 5C), similar to the ones reported for Tc-tor or Tc-tsl RNAi (our own data and15). However, we could not assess the contribution of either Tc-tor or Tc-ptth to pupariation as we were not able to establish an accurate system for timing Tribolium pupariation comparable to that established for Drosophila. We must highlight that the timing of pupariation in Drosophila is highly variable and susceptible to many environment inputs, which we were able to overcome using the techniques available for this species.

Figure 5. trk and ptth in Tribolium castaneum.

(A) Tc-trk mRNA is detected in the developing oocyte; no expression is found in nurse (NC) and follicular cells (FC). (B) Tribolium larva from control injection. (C) Tc-trk RNAi injections impair terminal patterning. (D) Tc-ptth mRNA is detected in two pairs of neurons in the larval brain.

Discussion

Here we provided evidences that Tsl participates in Tor activation both in the embryo and in the prothoracic gland. In the embryo, the TrkC108 cleaved form activates Tor in the absence of tsl function7, thereby suggesting that the latter is directly or indirectly involved in the processing of the Trk protein. Given the similarity between Trk and Ptth, the effect of Tsl in dpERK accumulation in the prothoracic gland and the effect of TrkC-108 and Tsl in advancing and delaying pupariation respectively, we propose that Tsl is similarly involved in Ptth processing in the prothoracic gland. It should be noted that in the prothoracic gland Tsl and Tor proteins are produced in the same cells while during embryogenesis Tor accumulates in the embryo upon synthesis while Tsl is synthesized and secreted from cells surrounding the oocyte. However, tor and tsl expression in distinct cell types is not an absolute requirement for Tor activation in embryogenesis as we have previously shown that tsl expression in the germline is also functional in Tor activation16. Thus, Tsl is detected in the cytoplasm of the cells where it is synthesised both in the ovary8,12 and in the prothoracic gland (Fig. 3), although the presence of a signal peptide in the protein suggests that it is secreted in both cases. Indeed, secreted Tsl is detected, upon specific processing, in the vitelline membrane, a particular type of extracellular matrix in the early embryo11; yet, we have not been able to detect Tsl at the extracellular matrix of the prothoracic gland cells.

As Tsl lacks any feature indicating that it has protease activity17,18, it has been suggested that this protein participates in the activation or nucleation of such an enzymatic complex2. In this scenario, similar proteins that could equally be activated/nucleated by Tsl could carry out the processing of Trk and Ptth. In this case, Tsl would be the common module in both events of Tor activation. Alternatively, the same players could be involved in both Trk and Ptth processing, in which case, the common module for Tor activation should be enlarged to also encompass the same processing complex. Final clarification of these two possibilities awaits the identification of the Trk (and Ptth) processing mechanism, which still remains elusive.

Conversely, fs(1)N, fs(1)ph and clos are required for Tor activation only in the early embryo indicating that Tsl does not need the function of these gene products to exert its function outside the embryo. Indeed, a relevant function of these three proteins is in vitelline membrane morphogenesis8,11,12,19,20. Therefore, it is likely that these proteins are recruited to anchor Tsl at the vitelline membrane and thus they participate in Tor activation exclusively in embryonic patterning. Of note, several observations have led to the proposal that anchorage of Tsl in the vitelline membrane serves to store it in a restricted domain until Tor activation in the early embryo21,22.

As for Tor, Toll signalling is a transduction pathway that was initially thought to act only in early embryonic patterning23 but does in fact participate in other signalling events24,25. However, in the case of Toll signalling, a single putative ligand, Spätzle (spz), acts both during embryonic patterning and in immunity (reviewed in26), while for Tor signalling different putative ligands are responsible for its activation in embryonic patterning and in the control of pupariation. Spz triggers Toll activation in many scenarios because the spz promoter drives its expression in several groups of cells27, possibly by distinct enhancers. In contrast, in the case of the Tor pathway a likely duplication might have generated two genes each with a distinct expression pattern and encoding the corresponding ligand for one of the two Tor activation events. The observation that Coleoptera but not Hymenopthera possess both trk and ptth orthologues suggest the putative duplication to have occurred at the origin of holometabolous insects. However and regarding tsl as the key element in ligand activation, multiple usage of the Tor pathway appears to have evolved by recruiting independent enhancers responsible for the distinct expression of the same gene.

In summary, Tor activation in oogenesis and in the prothoracic gland is linked to the following: a duplication and subsequent differential expression of trk and ptth; the acquisition of independent specific oogenesis and prothoracic gland enhancers in the tsl promoter; and the recruitment of proteins independently required for organ morphogenesis, in particular for eggshell assembly. The Drosophila EGFR resembles the case of Tor as another example of the repetitive use of the same receptor by different ligands in different contexts: Gurken in oogenesis and Spitz, Vein, and Keren during other stages of development (reviewed in28). Thus, we propose a combination of gene duplication, enhancer diversification and cofactor recruitment to be common mechanisms that allow the co-option of a single receptor-signalling pathway in distinct developmental and physiological functions.

Methods

Fly strains

The following strains were used: yw as a wild-type, UAS-trk29 UAS-trkC108 7, UAS-ptthHA4, phm-Gal49, daGal4 (Bloomington #8641), tsl0617 17, tsl(3B)-lacZ, tsl(3A)-lacZ, tsl(B)-lacZ16, tsl RNAi10, tsl417, tsl604 18, torXR, torPM 30, fs(1)N14 8, closc04152 12, and fs(1)N (#45489), clos (#39697) and fs(1)ph (#14413) RNAi from the VDRC31. Df(3R)cakiX-313 and CASKX-307 have been molecularly characterised32 and our previous work on the terminal system has shown the transheterozygote combination to behave as null allele for tsl. We used GFP balancers and mutant larvae selected accordingly.

Developmental timing analysis

Fertilised eggs were collected on peach juice agar plates. Collections were done at 2 h intervals during 2 days, generating at least 6-8 replicates per experiment. For each experiment, newly hatched first instar larvae were collected 24 hours after egg laying and transferred into vials with regular cornmeal food. Larvae were raised in groups of 25 to prevent overcrowding and the drying of fly food, at 25°C in a 12-h light/dark cycle. Pupariation was scored at continuous 2 h intervals, and the total time to pupariation for scored individuals was introduced on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Statistical analysis and data representation

In order to choose the most appropriate statistical tests to compare data samples we run the Shapiro-Wilk test33 on the single datasets. For all the tested datasets, the p-value was inferior to the alpha level of 0.05, indicating that data deviate significantly from a normally distributed population. Since normality of the data is one of the requirements of parametric statistics (i.e. Student's t-test), we decided to apply non-parametric statistics for pair wise comparisons. Mutant and control datasets were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test34, which is the non-parametric alternative to the t-test for independent samples. The R software package was used to perform all the tests and to generate the plots.

Immunostaining and in situ hybridization

Larval tissues were dissected in ice-cold PBS and fixed in 4% PBS-formaldehyde for 20 min (8% PBS-formaldehyde for detection with anti dpERK antibody). Incubations were o/n at 4°C with primary antibodies and for 2 h at r.t. with secondary antibodies. Samples were mounted in Fluoromount (Southern Biotech) or Vectashield with DAPI (Vectorlabs). We used anti-Spectrin (D.S.H.B. Iowa), anti-Tsl (see below), anti-dpERK (Cell signalling), anti-HA (3F10, Roche) and fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Tribolium whole mount in situ were performed according to35.

Generation of anti-Tsl polyclonal antibody

A fragment corresponding to aminoacids 20–353 was PCR amplified and cloned into pProEX-HTa. Transfected BL21 cells were grown in ZYP-505236 at 37°C o/n, the culture centrifuged and resuspended in a 8M urea buffer, the protein extract sonicated and purified with a Ni column (Sigma), the purified protein loaded in a 10% acrylamide gel and the corresponding band used to immunise rats. Immunopurification was performed in a Ni column and elution with 4M MgCl2. Eluted antibody was dialysed with PBS 1X and used at 1:50.

Tribolium RNAi injections

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was produced as described37. A clone containing the whole trk cDNA (700 nt.) was used as a template for in vitro transcription. Parental RNAi was performed as described37 and trunk dsRNA at a concentration of 0.5 µg/µl was injected into pupae. A total of 23 larvae out of 26 hatched (88.4%) displayed axis extension defects. A ptth cDNA (558nt.) was used as a template to generate dsRNA. No phenotype was observed upon ptth dsRNA injection (78/78). H2O was injected as control and no defective abdominal outgrowth phenotype was observed in the offspring (40/40). Cuticles of first-instar larvae were embedded in Hoyers mounting medium mixed with lactic acid (1:1) and analysed with differential interference contrast (DIC).

Author Contributions

MG, MF, XFM and JC designed the experiments. MG and MF performed the main experiments. MG, CM and XFM did the Tribolium experiments. JC wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed it.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Martín for the generation of the anti-Tsl antibody, M. O'Connor and L. Stevens for providing reagents, colleagues in the lab for discussions and M. Averof, A. Casali, J. de las Heras, D. Martín, M. Llimargas and E. Sánchez-Herrero for comments on the manuscript. We thank Y. Tomoyasu for teaching CM on Tribolium injections. This work has been supported by the “Generalitat de Catalunya”, the Spanish “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación” and Consolider-Ingenio 2010.

References

- Cavaliere V., Bernardi F., Romani P., Duchi S. & Gargiulo G. Building up the Drosophila eggshell: first of all the eggshell genes must be transcribed. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 237, 2061–2072 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M. & Casanova J. In and out of Torso RTK signalling. The EMBO journal 22, 1947–1952 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz K. F., Yamanaka N., Gilbert L. I. & O'Connor M. B. The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science 326, 1403–1405 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer Z. et al. Prothoracicotropic hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in Drosophila. Developmental cell 13, 857–871 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H. & Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M., Sprenger F. & Casanova J. Variation in the number of activated torso receptors correlates with differential gene expression. Development 122, 2313–2317 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali A. & Casanova J. The spatial control of Torso RTK activation: a C-terminal fragment of the Trunk protein acts as a signal for Torso receptor in the Drosophila embryo. Development 128, 1709–1715 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez G., Gonzalez-Reyes A. & Casanova J. Cell surface proteins Nasrat and Polehole stabilize the Torso-like extracellular determinant in Drosophila oogenesis. Genes & development 16, 913–918 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono H. et al. Spook and Spookier code for stage-specific components of the ecdysone biosynthetic pathway in Diptera. Developmental biology 298, 555–570 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M., Ventura G. & Casanova J. Two distinct but convergent groups of cells trigger Torso receptor tyrosine kinase activation by independently expressing torso-like. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 11660–11665 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. M., Beuchle D., Jurcsak J., Tong X. & Stein D. The Drosophila embryonic patterning determinant torsolike is a component of the eggshell. Current biology : CB 13, 1058–1063 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura G., Furriols M., Martin N., Barbosa V. & Casanova J. closca, a new gene required for both Torso RTK activation and vitelline membrane integrity. Germline proteins contribute to Drosophila eggshell composition. Developmental biology 344, 224–232 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal E. et al. Control of ecdysteroidogenesis in prothoracic glands of insects: a review. Peptides 31, 506–519 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. A. & Rybczynski R. Prothoracicotropic hormone. In: Gilbert LI, editor. Insect Endocrinology. New York: Academic Press. 1–62. (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schoppmeier M. & Schroder R. Maternal torso signaling controls body axis elongation in a short germ insect. Current biology : CB 15, 2131–2136 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M., Casali A. & Casanova J. Dissecting the mechanism of torso receptor activation. Mechanisms of development 70, 111–118 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savant-Bhonsale S. & Montell D. J. torso-like encodes the localized determinant of Drosophila terminal pattern formation. Genes & development 7, 2548–2555 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. R., Raibaud A. & Ollo R. Terminal pattern elements in Drosophila embryo induced by the torso-like protein. Nature 367, 741–745 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degelmann A., Hardy P. A. & Mahowald A. P. Genetic analysis of two female-sterile loci affecting eggshell integrity and embryonic pattern formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 126, 427–434 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernilogar F. M., Fabbri F., Andrenacci D., Taddei C. & Gargiulo G. Drosophila vitelline membrane cross-linking requires the fs(1)Nasrat, fs(1)polehole and chorion genes activities. Development genes and evolution 211 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G., Johnston P. & Lawrence P. A. Control of Drosophila body pattern by the hunchback morphogen gradient. Cell 69, 237–249 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueron M. I., Mauzy-Melitz D. & Waring G. L. Drosophila dec-1 eggshell proteins are differentially distributed via a multistep extracellular processing and localization pathway. Developmental biology 225 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin M. P. & Anderson K. V. A conserved signaling pathway: the Drosophila toll-dorsal pathway. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 12, 393–416 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosetto M., Engstrom Y., Baldari C. T., Telford J. L. & Hultmark D. Signals from the IL-1 receptor homolog, Toll, can activate an immune response in a Drosophila hemocyte cell line. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 209, 111–116 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Nicolas E., Michaut L., Reichhart J. M. & Hoffmann J. A. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 86, 973–983 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valanne S., Wang J. H. & Ramet M. The Drosophila Toll signaling pathway. J Immunol 186, 649–656 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisato D. & Anderson K. V. The spatzle gene encodes a component of the extracellular signaling pathway establishing the dorsal-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Cell 76, 677–688 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo B. Z. Regulating the dynamics of EGF receptor signaling in space and time. Development 132, 4017–4027 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali A. Caracterització del producte del gen trunk i el seu paper en l'activació del receptor Torso a Drosophila. PhD Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach T. & Wieschaus E. Maternal-effect mutations altering the anterior-posterior pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Development genes and evolution 195, 302–317 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G. et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448, 151–156 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. R. & Ollo R. A new Drosophila Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (Caki) is localized in the central nervous system and implicated in walking speed. The EMBO journal 15, 1865–1876 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. S. JSTOR: Biometrika, Vol. 52, No. 3/4 (Dec., 1965), pp. 591–611. Biometrika (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Mann H. B. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics (1947). [Google Scholar]

- Schinko J., Posnien N., Kittelmann S., Koniszewski N. & Bucher G. Single and Double Whole-Mount In Situ Hybridization in Red Flour Beetle (Tribolium) Embryos. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2009, pdb.prot5258 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein expression and purification 41, 207–234 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip B. N. & Tomoyasu Y. Gene knockdown analysis by double-stranded RNA injection. Methods Mol Biol 772, 471–497 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian R. et al. SATCHMO-JS: a webserver for simultaneous protein multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction. Nucleic acids research 38, W29–W34 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]