Abstract

Slug (Snail2) plays critical roles in regulating the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) programs operative during development and disease. However, the means by which Slug activity is controlled remain unclear. Herein we identify an unrecognized canonical Wnt/GSK3β/β-Trcp1 axis that controls Slug activity. In the absence of Wnt signaling, Slug is phosphorylated by GSK3β and subsequently undergoes β-Trcp1–dependent ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. Alternatively, in the presence of canonical Wnt ligands, GSK3β kinase activity is inhibited, nuclear Slug levels increase, and EMT programs are initiated. Consistent with recent studies describing correlative associations in basal-like breast cancers between Wnt signaling, increased Slug levels, and reduced expression of the tumor suppressor Breast Cancer 1, Early Onset (BRCA1), further studies demonstrate that Slug—as well as Snail—directly represses BRCA1 expression by recruiting the chromatin-demethylase, LSD1, and binding to a series of E-boxes located within the BRCA1 promoter. Consonant with these findings, nuclear Slug and Snail expression are increased in association with BRCA1 repression in a cohort of triple-negative breast cancer patients. Together, these findings establish unique functional links between canonical Wnt signaling, Slug expression, EMT, and BRCA1 regulation.

Keywords: invasion, phosphoserine, E-cadherin, vimentin, fibronectin

Slug (also termed Snail2) is a C2H2 zinc-finger transcriptional repressor belonging to the three-member family of Snail proteins (Snail, Slug, and Smuc) (1, 2). First recognized for its participation in events associated with the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) programs that characterize early development, more recent studies have identified postnatal roles for Slug in a wide variety of carcinomatous states (1–7). To date, Slug expression has been linked to cancer stem cell formation, cell cycle regulation and apoptosis as well as invasion and metastasis (1–7). However, the Slug protein, like that of Snail, is rapidly turned over by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in vivo, and the key factors responsible for regulating Slug protein stability and activity remain largely undefined (2, 8). Interestingly, recent studies have identified a subset of breast cancer patients (the so-called basal-like breast carcinoma phenotype) whose lesions display an EMT-like signature associated with increased Wnt signaling, up-regulated Slug expression, and epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor BRCA1 (7, 9–13). Despite these associations, however, no molecular pathways have been established that functionally link these potentially disparate phenotypes together.

Herein we demonstrate that Slug protein stability and activity are controlled by a heretofore undescribed GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation process that primes phospho-Slug for ubiquitination by the E3 ligase β-Trcp1 and its subsequent proteasomal degradation. In the presence of canonical Wnt agonists, however, GSK3β activity is suppressed and Slug phosphorylation is blocked, thereby allowing Slug protein levels and activity to increase. Further, in response to Wnt signaling, stabilized Slug is not only capable of driving cancer cell EMT programs and tissue-invasive activity, but also serves to repress BRCA1 expression by binding to the BRCA1 promoter and recruiting the histone demethylase LSD1. Together, these studies identify a unique Wnt/GSK3β/Slug axis that controls cancer cell EMT programs while coordinately regulating BRCA1 expression.

Results

Slug, a GSK3β Substrate.

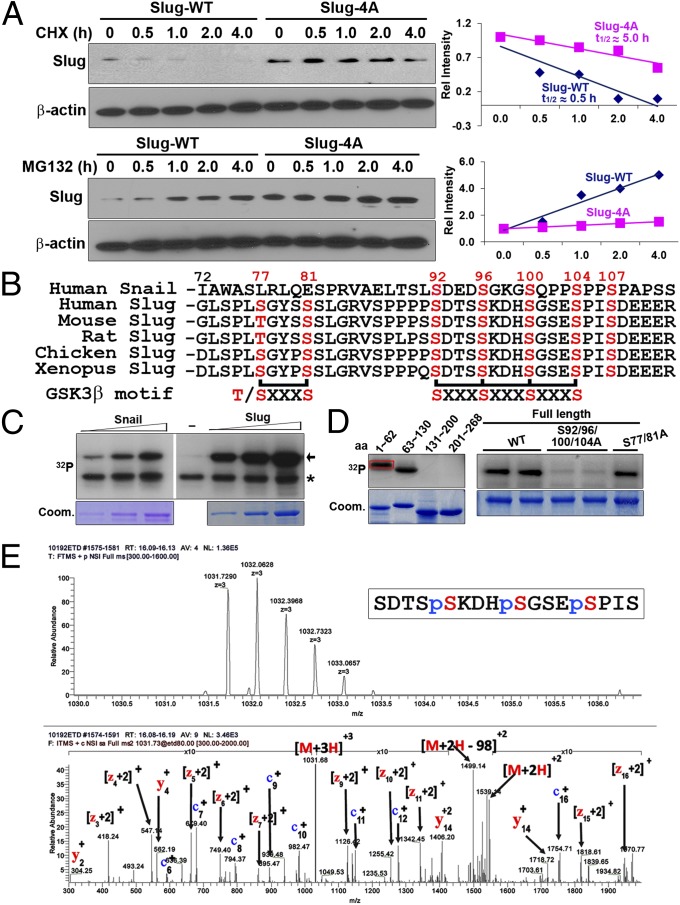

Consistent with the rapid turnover of Slug protein in a model Xenopus system (8), the t½ of epitope-tagged Slug is ∼0.5 h in transfected MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells, and the protein only accumulates to detectable levels in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). Given the short half-life of Slug, the protein sequence of Slug and the similarly short-lived Snail protein were aligned to identify conserved domains that might similarly affect Slug stability (8, 14–17). Interestingly, Slug contains a previously unrecognized GSK3β phosphorylation motif similar to that found in Snail (Fig. 1B) (14–17). As such, either recombinant Slug or Snail was expressed in Escherichia coli and the recombinant protein incubated with GSK3β in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. As shown in Fig. 1C, Slug, like Snail, is phosphorylated by GSK3β in a dose-dependent fashion. To further refine the search for phosphorylated residues, four nonoverlapping Slug fragments (aa 1–62, 63–130, 131–200, and 201–286) were generated and incubated with GSK3β and [γ-32P]ATP. Only the domain encompassing amino acid residues 63–130, wherein the putative GSK3β recognition motif is embedded, serves as a specific substrate for phosphorylation (Fig. 1D; the nonspecific band that appears in the incubation mixture with the aa 1–62 fragment does not colocalize with the Coomassie-stained peptide). Because at least two potential GSK3β consensus motifs can be located within the 63–130 fragment (Fig. 1B) (18), each of the serine residues was mutated to an alanine residue within the context of full-length Slug, and GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation was reassessed. Compared with the level of phosphorylation observed in wild-type Slug (Slug-WT), the phosphorylation of the Slug S92/S96/S100/S104 → A92/A96/A100/A104 mutant (Slug-4A) is almost completely abolished, whereas the phosphorylation status of the S77/S81 → A77/A81 mutant is unaffected (Fig. 1D). Consistent with these results, (i) following incubation of recombinant Slug with recombinant GSK3β and ATP, mass spectroscopy identifies phosphorylated residues at amino acid residues Ser-96, 100, and 104 (Fig. 1E); (ii) the half-life of Slug-4A increases 10-fold relative to Slug-WT to 5.0 h; and (iii) Slug-4A levels remain stable in the transfected cells either in the absence or presence of MG132 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). Whereas a homologous serine-rich domain found in Snail regulates its nuclear localization as a function of its ability to mask a nuclear export signal embedded in proximity to its zinc-finger domain, Slug does not contain a similar nuclear export motif (19). Consequently, Slug nuclear localization is unaffected by the 4A mutation (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Slug is a GSK3β substrate. (A, Upper) MCF7 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-Slug-WT or -4A were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for varying time intervals and analyzed by Western blotting (Left), and the protein levels in the indicated cells were quantified by densitometry as a function of time (Right). (Lower) Transfected MCF7 cells were treated with MG132 for the indicated time intervals and analyzed by Western blotting (Left), and the protein levels were quantified by densitometry as a function of time (Right). (B) Sequence alignment of human Snail with human, mouse, rat, chicken, and Xenopus Slug showing the relative positions of the two potential GSK3β consensus phosphorylation motifs. (C) Recombinant GSK3β was incubated with increasing amounts of bacterially expressed, purified GST-Slug or GST-Snail in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction mixtures were resolved by SDS/PAGE with Snail/Slug proteins visualized by autoradiography. Arrow, phosphorylation of Snail/Slug; asterisk, autophosphorylation of GSK3β. Coomassie stains (Coom.) are shown for increasing amounts of Snail/Slug proteins. (D, Left) GSK3β was incubated with a series of purified GST-Slug peptides. (Right) GSK3β was incubated with GST-Slug-WT or the indicated serine-to-alanine mutants. Coomassie stains for the peptides/mutants are shown. Rectangle (red) outlines a nonspecific phosphorylation band that does not align with the Coomassie-stained peptide. (E) GSK3β was incubated with GST-Slug in the presence of cold ATP. The reaction mixtures were resolved by SDS/PAGE, subjected to mass spectrometry analysis, and the phosphorylation sites identified.

GSK3β-β-Trcp1–Dependent Phosphorylation/Ubiquitination Axis Regulates Slug Protein Levels.

To confirm GSK3β-Slug interactions in vivo, 293T cells were cotransfected with either FLAG-tagged Slug-WT or the Slug-4A mutant in combination with HA-tagged GSK3β in the presence of MG132. Following immunoprecipitation of GSK3β with an anti-HA antibody and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG, GSK3β is found in association with both wild-type and mutant Slug (Fig. S2). In reciprocal fashion, Slug-GSK3β binding is confirmed following immunoprecipitation of wild-type or mutant Slug with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting with anti-HA (Fig. S2). The binding interactions detected between Slug and GSK3β in vivo are likely direct; bacterially expressed GST fusion proteins of Slug-WT or Slug-4A bind HA-tagged GSK3β that had been translated in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Fig. S2).

Following GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation, multiple substrates are consequently destined for degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (18). As such, Slug-WT was expressed in 293T cells in the absence or presence of the synthetic GSK3 inhibitors SB216763, CHIR99021, or BIO (20) and with or without MG132. Although exogenous Slug protein is only marginally detectable in transfected 293T cells, Slug protein levels are increased dramatically in cells treated with GSK3 inhibitors alone, MG132 alone, or GSK3 inhibitors and MG132 in combination (Fig. S2). Likewise, when either GSK3 or proteasome activity is inhibited in MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells or SK-MEL-5 melanoma cells, endogenous Slug protein levels increase without affecting Slug mRNA levels (Fig. S2). Although either GSK3β or GSK3α could potentially phosphorylate the serine-rich Slug motif (18, 20), specific silencing of GSK3β alone suggests that this isoform plays the major role in regulating Slug levels (Fig. S2). Whereas either GSK3 isoform may phosphorylate Slug in a cell context-specific fashion, the half-life of the nonphosphorylatable Slug-4A mutant is equally stable in the absence or presence of GSK3 inhibitors or proteasome inhibitors (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2).

Previous reports have demonstrated that GSK3β-phosphorylated substrates are ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin ligase family members such as FBXW7, FBX4, or β-Trcp1 (18, 21). Preliminary studies revealed that overexpression of either FBXW7 or FBX4 did not affect Slug protein stability, but given the structure/function similarities between Slug and Snail, and the dominant role played by β-Trcp1 as the ligase responsible for Snail ubiquitination (14–17), potential interactions between Slug and β-Trcp1 were alternately assessed—despite the fact that Slug (unlike Snail) does not contain a classic, β-Trcp1 recognition site (i.e., DSGXXS) (21). To this end, MCF-7 cells were cotransfected with mock or myc-tagged β-Trcp1 in combination with either FLAG-tagged Slug-WT or Slug-4A, and the cell lysates were subjected to ubiquitination analysis. Following Slug immunoprecipitation, β-Trcp1 is only found in association with Slug-WT and not the unphosphorylatable Slug-4A mutant (Fig. S3). Furthermore, Slug-WT is heavily ubiquitinated relative to Slug-4A (Fig. S3). Consistent with these findings, β-Trcp1 silencing increases the steady-state levels of Slug-WT, but not Slug-4A (Fig. S3). Conversely, β-Trcp1 overexpression lowers Slug-WT levels without affecting Slug-4A levels (Fig. S3). Together, these data are consistent with a model wherein β-Trcp1 recognizes GSK3β-phosphorylated Slug and catalyzes its ubiquitination.

Recent studies have demonstrated that Xenopus Partner of paired, as well as its mammalian homolog, FBXL14, can also support Slug ubiquitination via a pathway that operates independently of GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation (8, 22). As such, MCF-7 cells (which express endogenous FBXL14) were cotransfected with an FBXL14 shRNA (or alternatively, a scrambled control) and either Slug-WT or Slug-4A (Fig. S3). Under these conditions, FBXL14 silencing increases the steady-state protein levels of both wild-type and mutant Slug without affecting Slug mRNA levels (Fig. S3). Hence, the regulation of Slug protein levels falls under the dual regulation of GSK3β-dependent and independent ubiquitination pathways that are mediated, respectively, by β-Trcp1 and FBXL14 (Fig. S3).

Wnt-GSK3β Signaling Pathway Regulates Slug-Dependent EMT.

Canonical Wnt signaling pathways activate Snail-dependent EMT programs by increasing Snail protein levels as a consequence of preventing its GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (15–17). To determine whether Wnt signaling similarly affects Slug-dependent EMT programs, MCF-7 cells were transfected with Slug-WT or Slug-4A expression vectors and incubated with Wnt3a. Under these conditions, Slug-WT protein levels are markedly increased in tandem with endogenous β-catenin levels and decreased nuclear GSK3β activity (without altering Slug mRNA expression) (Fig. 2A). By contrast, Wnt3a does not affect the stability of Slug-4A (Fig. 2A). Complementing these results, MCF-7 cells engineered to stably express Slug-WT only marginally increase Slug protein levels without affecting (i) E-cadherin or vimentin protein levels or (ii) mRNA levels for CDH1, OCLN, VIM, or FN (Fig. 2B). In stable lines expressing the nonphosphorylatable Slug-4A mutant, however, markedly higher Slug protein levels are detected, whereas E-cadherin protein expression is repressed and vimentin protein levels are increased (Fig. 2 B and C). In tandem with these results, Slug-4A up-regulates VIM and FN mRNA levels and decreases CDH1 and OCLN mRNA expression (Fig. 2B). As expected, Slug-4A is also a more powerful repressor of E-cadherin reporter activity than Slug-WT, consistent with the greater stability of the mutant protein (Fig. 2D). Finally, when the ability of stable MCF-7 transfectants expressing Slug-WT versus Slug-4A to drive basement membrane invasion—the sine qua non of EMT programs (1, 2)—is assessed in a chick chorioallantoic membrane assay (CAM) (23), the stabilized Slug mutant triggers an approximately fourfold increase in invasion relative to Slug-WT (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

A canonical Wnt/GSK3β signaling pathway regulates Slug-dependent EMT. (A) MCF7 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged Slug-WT or -4A were treated with or without recombinant Wnt3a (100 ng/mL). Total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (Left) or quantitative RT-PCR (Right). Nuclear extracts were analyzed for GSK3β kinase activity (Right). **P < 0.01, Wnt3a vs. vehicle. (B) MCF7 cells stably expressing mock, Slug-WT, or Slug-4A expression vectors were analyzed by Western blotting (Left) or qRT-PCR (Right). Inset, relative Slug mRNA levels in -WT or -4A expressing cells. **P < 0.01, 4A vs. mock. (C) The morphology of MCF7 cells stably expressing mock, Slug-WT, or Slug-4A expression vectors as assessed by phase-contrast microscopy (Upper) or immunofluorescence following staining with anti–E-cadherin antibody (Lower). (D) (Left) MCF7 cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts of mock, Slug-WT, or -4A expression vectors in combination with an E-cadherin promoter reporter construct (25 ng) and analyzed by luciferase assay. (Right) Slug protein and mRNA levels in -WT or -4A expressing cells. (E) (Left) MCF7 cells stably expressing mock, Slug-WT, or Slug-4A expression vectors were labeled with fluorescent beads (green) and cultured atop the live chick CAM for 4 d. CAMs were fixed and stained with an anti-chicken type IV collagen antibody (red). Dashed lines mark the CAM basement membrane. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (Right) Relative invasion was determined. **P < 0.01, 4A vs. Mock; ##P < 0.01, 4A vs. WT.

Unexpected Link Between Snail/Slug-Induced EMT and BRCA1 Repression.

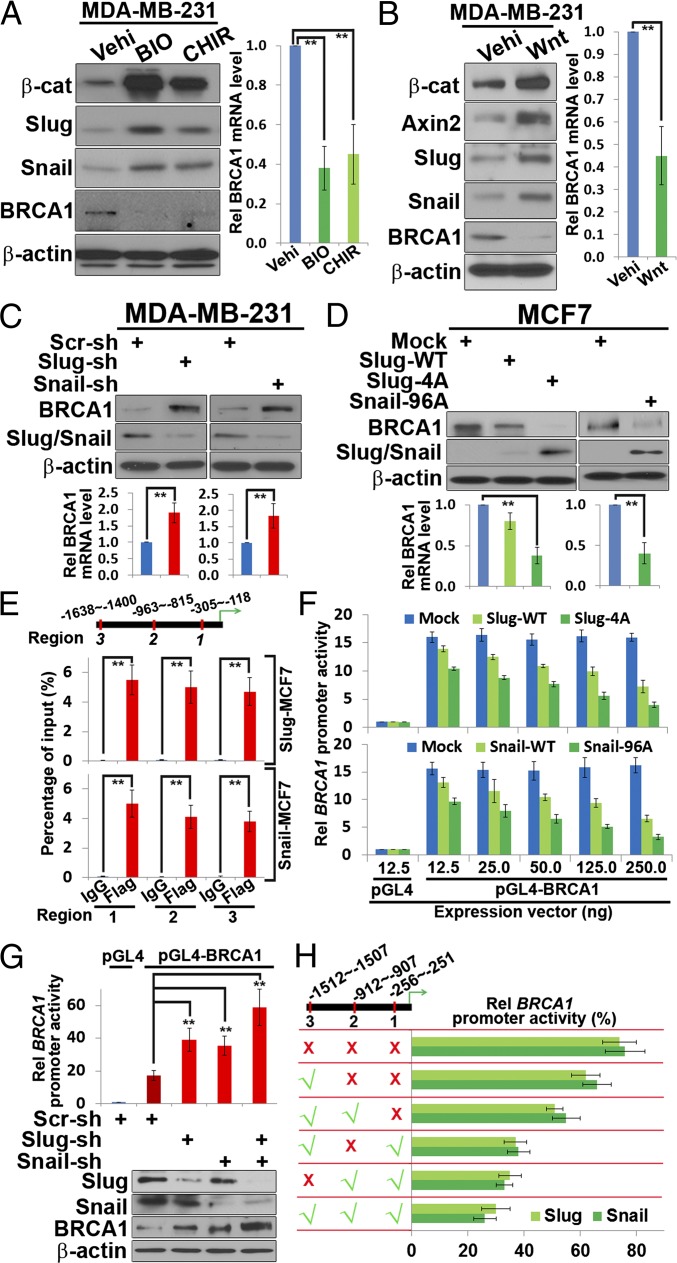

In searching for signaling pathways that might affect Slug protein stability or function, the tumor suppressor BRCA1 has recently been reported to stabilize Slug protein levels in mammary epithelial cells (11). However, as opposed to results obtained in nontransformed mammary epithelial cells (11), when endogenous BRCA1 expression is silenced in either Slug-WT–transfected MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells, significant changes in Slug protein levels are not detected (Fig. S4). Interestingly, however, the BRCA1 promoter contains multiple Snail family-responsive E-boxes (see below) (1, 2), raising the possibility that the GSK3β-Slug as well as the GSK3β-Snail axis may serve as upstream regulators of BRCA1 expression. Indeed, when the levels of either endogenous Slug or Snail are increased by treating MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells with the GSK3 inhibitors BIO or CHIR99021, or alternatively Wnt3a, both Slug and Snail protein levels increase [in tandem with levels of the alternate GSK3β target, β-catenin (18)], whereas BRCA1 mRNA and protein levels are suppressed (Fig. 3 A and B). Conversely, when either endogenous Slug or Snail expression is silenced in MDA-MB-231 cells, BRCA1 mRNA and protein levels increase in tandem with BRCA1 promoter activity (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4). The ability of Slug or Snail to repress endogenous BRCA1 expression is also confirmed in MCF-7 cells transfected with either Slug-WT, Slug-4A, or a stable Snail mutant [Snail (Ser96 → Ala)] (15, 16) (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

A Wnt/GSK3β/Slug axis regulates BRCA1 expression. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the indicated GSK3 inhibitors (A) or recombinant Wnt3a (B) and analyzed by Western blotting or qRT-PCR. **P < 0.01. (C) Cell lysates from MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing Scr-, Slug- or Snail-shRNAs were subjected to Western blotting or qRT-PCR analyses, respectively. **P < 0.01. (D) MCF7 cells stably expressing mock, Slug-WT, Slug-4A, or Snail-96A expression vectors were analyzed by Western blotting or qRT-PCR. **P < 0.01. (E) Snail/Slug-E-cadherin or Snail/Slug-BRCA1 promoter interactions in MCF7 cells stably expressing Slug-WT or Snail-WT expression vectors were assessed within the indicated promoter regions (marked with red lines) by ChIP/qPCR. **P < 0.01. (F) MCF7 cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts of mock, Slug-WT, Slug-4A, Snail-WT, or Snail-96A expression vectors in combination with a BRCA1 reporter construct (25 ng) and relative promoter activities determined by luciferase assay. (G) MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing Scr-, Slug-, Snail-, or Slug/Snail-shRNAs were transfected with a BRCA1 promoter or control reporter construct and the cell lysates were subjected to luciferase assay (Upper) and Western blot analysis (Lower). **P < 0.01. (H) MCF7 cells were cotransfected with mock, Slug-4A, or Snail-96A expression vectors in combination with wild-type or mutated BRCA1 promoter reporter constructs, and relative promoter activity was determined by luciferase assay.

To determine whether Slug or Snail represses BRCA1 expression by binding to the BRCA1 promoter E-boxes, Slug- or Snail-transfected MCF-7 cells were fixed, genomic DNA-sheared, and subjected to ChIP analysis. As expected, a DNA fragment containing the three E-boxes found in the E-cadherin promoter can be amplified from the genomic DNA immunoprecipitated from either wild-type Slug or Snail stable transfectants as well as from transfectants expressing the nonphosphorylatable Slug or Snail mutants (Fig. S4). Likewise, three fragments targeting the three consensus E-boxes located within the BRCA1 promoter [i.e., CANNTG (1)] are amplified from the immunoprecipitated genomic DNA isolated from either the Slug or Snail wild-type and mutant transfectants (Fig. 3E and Fig. S4). The ability of Slug or Snail promoter binding interactions to repress BRCA1 reporter activity is further confirmed in (i) MCF-7 cells cotransfected with the full-length BRCA1 promoter (i.e., from bp −1582 to +36) and either wild-type or mutant Slug or Snail (Fig. 3F) and (ii) transfected MDA-MB-231 cells wherein BRCA1 reporter activity and protein levels are de-repressed following either the silencing of Slug or Snail alone or in combination (Fig. 3G). Mutational analysis of the BRCA1 promoter demonstrates that each of three E-boxes located within this fragment support Slug or Snail repressive activity, with the third E-box (from −256 to −251) displaying the strongest activity (Fig. 3H).

Snail/Slug–LSD1 Axis Regulates BRCA1 Expression.

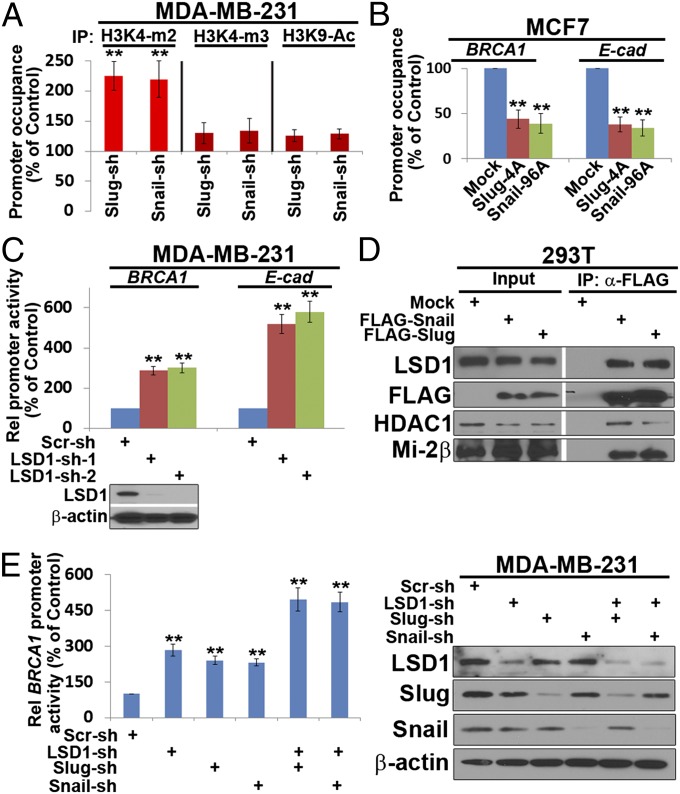

The ability of Snail family members to repress transcriptional activity of target genes has been linked to the recruitment of histone modifying cofactors (1, 2, 24–26). To determine whether the de-repression of BRCA1 expression observed following Slug or Snail silencing is linked to histone modifications within its promoter region, ChIP analyses were performed in Slug- or Snail-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells using antibodies that recognize di- or trimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me2 or H3K4me3) or acetylated H3K9 (H3K9Ac), histone marks associated with increased transcriptional activity (1, 2, 24–26). As shown in Fig. 4A, the level of H3K4me2, but not of H3K4me3 or H3K9Ac, is increased at the BRCA1 promoter following Slug or Snail silencing. Conversely, when MCF-7 cells are transfected with stable Slug-4A or Snail-96A mutants, the level of H3K4me2 is decreased at the BRCA1 as well as E-cadherin promoters (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

LSD1-dependent Slug-mediated BRCA1 repression. (A) Lysates from MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing Scr-, Slug-, or Snail- shRNA were subjected to ChIP analysis using antibodies directed against H3K4me2, H3K4me3, or H3K9Ac and BRCA1 occupancy was determined by qPCR. **P < 0.01. (B) Cell lysates from MCF7 cells stably expressing mock, Snail-96A, or Slug-4A expression vectors were subjected to ChIP analysis using anti-H3K4me2 antibody and BRCA1 or E-cadherin occupancy was determined by qPCR. **P < 0.01. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing Scr-shRNA, LSD1-shRNA-1 or LSD1-shRNA-2 were cotransfected with either a BRCA1 or E-cadherin promoter construct, and the cell lysates were subjected to luciferase assays. Inset, LSD1 protein levels in the indicated cell lysates. **P < 0.01. (D) 293T cells were cotransfected with mock, FLAG-tagged Snail, or Slug expression vectors, and whole cell extracts prepared, subjected to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation, and analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. (E) MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing Scr-shRNA or LSD1-shRNA-1 were transduced with lentiviruses expressing Scr-shRNA, Slug-shRNA, or Snail-shRNA. The cells were transfected with a BRCA1 promoter construct, and the cell lysates were subjected to luciferase assay (Left) and Western blotting analysis (Right). **P < 0.01, treated vs. control.

In considering potential mechanisms by which Slug or Snail modifies H3K4 methylation status, Snail can associate with the histone demethylase LSD1 (25, 26). Indeed, when LSD1 expression is silenced, both BRCA1 and E-cadherin promoter activities are increased (Fig. 4C). LSD1 can be found in complex with either epitope-tagged Snail or Slug as well as previously described components of the Mi-2/nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex, HDAC1 and Mi-2β (Fig. 4D) (27). Although the bulk of repressive activity exerted by Snail or Slug on BRCA1 expression could be linked to LSD1, targeting both LSD1 and Snail or Slug exerts even stronger effects on BRCA1 promoter activity (Fig. 4E). Taken together, Wnt/GSK3β-dependent regulation of Slug as well as Snail activities integrates the control of BRCA1 expression within the confines of a general EMT program.

Slug/Snail–BRCA1 Axis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer.

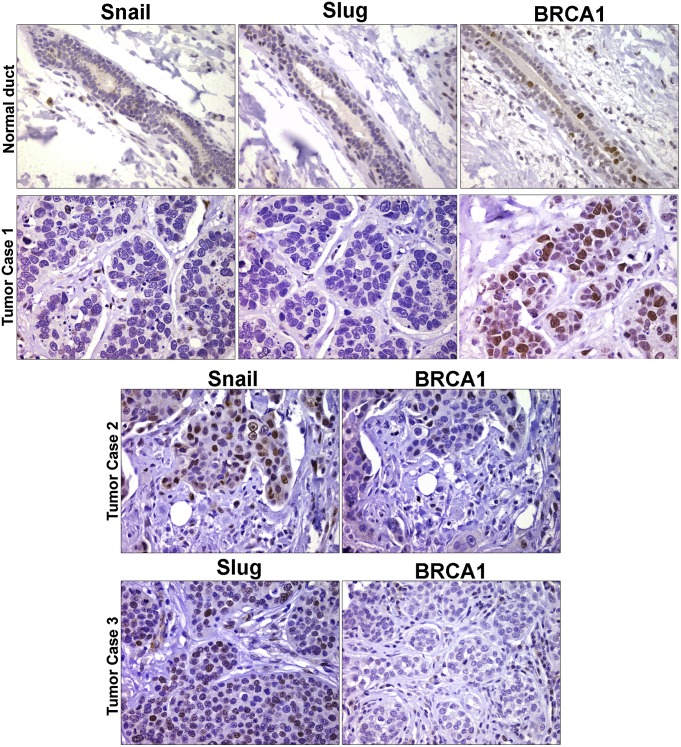

Given previously described associations between basal-like breast cancers and reduced BRCA1 expression (12, 13), tissue microarrays from 113 primary invasive breast carcinoma patients (48 ER-positive, 8 HER-2/neu over-expressing and 57 triple-negative) were interrogated for Snail and/or Slug expression in tandem with BRCA1 by immunohistochemical analysis (see SI Materials and Methods for details). Segregating the patient cohort into BRCA1low versus BRCA1high and nuclear Snail/Slug+ versus Snail/Slug− groups, a statistically significant association can be identified wherein ∼60% of the BRCA1low-scoring patients are also Snail/Slug+ (Table 1 and Fig. 5). Further characterization of the dataset indicates that 57 of the 113 samples are categorized as triple-negative breast cancers, with 65% of the patient tissues (i.e., 37 patients) falling into the BRCA1low subgroup. Of this patient cohort, 65% of the samples (24 patients) expressed either Snail or Slug (Fig. S5). Hence, the majority of triple-negative breast cancer patients expressing low levels of BRCA1 coexpress either nuclear Snail or Slug.

Table 1.

Association between BRCA1 and Snail and Slug levels in breast cancer

| Snail+ and/or Slug+ | Snail− and/or Slug− | Total | |

| BRCA1low | 26 (59%) | 20 (30%) | 46 |

| BRCA1high | 18 (41%) | 49 (70%) | 67 |

| Total | 44 | 69 | 113* |

*Pearson χ2 test, P = 0.0015.

Fig. 5.

Snail/BRCA1 expression in human breast cancer tissues. Representative sections stained for Snail, Slug, or BRCA1 from normal breast tissues and three triple-negative breast cancer samples are shown.

Discussion

In breast cancer, Snail activity falls under the regulation of a Wnt/GSK3 signaling cascade (1, 2, 15, 16). However, given sequence divergence between Slug and Snail, it has been assumed that distinct mechanisms of regulation have evolved to specifically control Slug posttranscriptional activity (8). Here we describe, however, that a conserved 92SXXXSXXXSXXXS104 motif found in Slug—and shared with Snail—serves as a GSK3β recognition motif in vitro and in vivo. Although caution should be exercised in extrapolating GSK3β-dependent in vitro phosphorylation events to the in vivo setting (17, 18), mass-spectroscopy analyses of Slug phosphorylation in intact cells have confirmed phosphorylation at 100Ser, 104Ser, and 107Ser (SI Text). Nevertheless, attempts to identify all phosphorylation sites can be hampered by ubiquitination-associated masking as well as the presence of phosphatases capable of de-phosphorylating Snail family members (2, 17).

Following its GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation, Slug is ubiquitinated by β-Trcp1, despite the absence of a classic destruction box sequence (21). In this regard, an increasing number of GSK3β targets have been identified that contain noncanonical, β-Trcp1 recognition motifs (21). Acidic phosphomimetic residues (D/E) can function as alternate pS/T sites within destruction box-like motifs, raising the possibility that a 103EpSPTSD109 sequence found in Slug serves as the β-Trcp1 target (underline indicates critical residues), and further studies are underway to address this issue (21, 28). Nevertheless, Slug ubiquitination is not solely controlled by its GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation; Slug can also be targeted by the ubiquitin ligase FBXL14 (8, 22).

Despite interest in the association between canonical Wnt signaling and the induction of Slug-dependent EMT-like programs in basal-like breast cancers (9–11, 29, 30), the molecular mechanisms underlying the documented association between this cancer subtype and the down-regulated expression of the tumor suppressor BRCA1 have not been defined previously (12, 31). Women carrying germ line mutations in BRCA1 can develop aggressive basal-like breast cancers wherein dysregulated Slug expression has been proposed to alter mammary progenitor cell fate (11). Interestingly, however, sporadic breast cancers, particularly those falling within the basal-like subtype, display decreased BRCA1 expression in the absence of genetic mutation (12, 31, 32). In considering potential mechanisms by which Snail family members repress BRCA1 expression, three lines of evidence were considered. First hypoxia, an established inducer of Snail and Slug expression (9, 33), has been recently shown to trigger the epigenetic regulation and silencing of the BRCA1 promoter via LSD1-mediated decreases in H3K4 methylation (31). Second, LSD1 is up-regulated in estrogen-negative breast cancers, a phenotype commonly observed in the basal-like carcinomas (34). Third, Snail family members have been shown to recruit a growing number of histone modifiers, including LSD1, to exert epigenetic control over targeted genes (25, 26). Whereas LSD1 binds to the Snail SNAG domain (25, 26), this motif is highly conserved in Slug as well (35). Indeed, Slug as well as Snail binds LSD1 and represses BRCA1 expression by recruiting the H3K4 demethylase to the targeted promoter. Interestingly, whereas Slug, like Snail, can induce Zeb1 and Zeb2 expression (30), neither of the ZEB family members plays significant roles in Slug- or Snail-mediated BRCA1 repression (Fig. S6).

In sampling a cohort of breast cancer tissues, Slug and/or Snail expression was, as described recently (36), almost entirely confined to triple-negative tissues. Among the BRCA1low subpopulation, 24 of 37 patients expressed Slug or Snail, supporting the contention that the Snail/Slug/BRCA1 axis is operative in vivo. Of these 24 patients, 10 samples were positive for Slug and Snail in tandem or Slug alone (Table 1). The other 14 patients in this subset expressed Snail alone, but we cannot rule out differences in the sensitivity between the anti-Snail and anti-Slug antibodies. The functional impact of Snail/Slug-dependent BRCA1 repression remains to be determined, but BRCA1 plays important roles in controlling DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoint regulation, transcription, progenitor cell fate determination, and even cell motility (37, 38). Because many of these BRCA1-regulated responses likewise fall under the purview of Snail/Slug expression (1, 2), coupled with the fact that Snail-dependent repression may extend to the structurally distinct BRCA2 gene (39), we posit that normal and neoplastic cell functions are integrated through reciprocating interactions that operate between these two networks. Indeed, preliminary studies indicate that both Slug and Snail can induce EMT programs associated with Zeb1/2, vimentin, and fibronectin expression while repressing BRCA1 as well as BRCA2 in tandem with sensitizing mammary epithelial cells to etoposide-mediated DNA damage (Fig. S7). This effect, coupled with the known anti-apoptotic activities of Slug and Snail (1, 2), raises the interesting possibility that these transcription factors may promote chromosome instability in neoplastic states.

The ability of canonical Wnt signaling to coregulate Slug and Snail is consistent with recent studies documenting dual roles for these transcriptional repressors in events ranging from TGFβ signaling to vitamin D receptor expression and metastasis (1, 2). Nevertheless, Slug and Snail protein levels are not necessarily coregulated under all circumstances. Just as the Wnt-mediated stabilization of β-catenin requires accessory signaling cascades to promote nuclear localization (1, 2), the Wnt-dependent stabilization of Slug and Snail must work in tandem with the broad spectrum of growth factors, cytokines, microenvironmental conditions, and mutations known to selectively or jointly increase Slug or Snail gene expression (1, 2, 14–16, 22, 40–42). Regardless of the specific circumstances operative in vivo, our findings establish a heretofore unrecognized link between the canonical Wnt signal transduction cascade and the activation of Slug-dependent transcriptional programs.

Materials and Methods

Detailed protocols regarding cell culture, plasmid, siRNA and shRNA construction, pharmacologic treatment of cells, cell extract preparation, antibodies, immunoprecipitation, in vitro kinase assays, recombinant protein purification, chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis, invasion assays and patient sample immunohistochemistry are described in SI Text. The breast cancer patient cohort has been described previously (see SI Text). Use of human materials was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board with informed consent obtained from all patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant CA116516 (to S.J.W.), CA107469 (to C.G.K.), CA125577 (to C.G.K.), CA154224 (to C.G.K.), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation Grant (to S.J.W.). Work on this study was also supported by Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Cell and Molecular Biology Core NIH Grant P60 DK020572.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1205822109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieto MA, Cano A. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition under control: Global programs to regulate epithelial plasticity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta PB, et al. The melanocyte differentiation program predisposes to metastasis after neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1047–1054. doi: 10.1038/ng1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casas E, et al. Snail2 is an essential mediator of Twist1-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:245–254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittal MK, Singh K, Misra S, Chaudhuri G. SLUG-induced elevation of D1 cyclin in breast cancer cells through the inhibition of its ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:469–479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.164384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volinia S, et al. Breast cancer signatures for invasiveness and prognosis defined by deep sequencing of microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3024–3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo W, et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lander R, Nordin K, LaBonne C. The F-box protein Ppa is a common regulator of core EMT factors Twist, Snail, Slug, and Sip1. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:17–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storci G, et al. The basal-like breast carcinoma phenotype is regulated by SLUG gene expression. J Pathol. 2008;214:25–37. doi: 10.1002/path.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMeo TA, et al. A novel lung metastasis signature links Wnt signaling with cancer cell self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5364–5373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proia TA, et al. Genetic predisposition directs breast cancer phenotype by dictating progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner NC, et al. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez ME, et al. Downregulation of EZH2 decreases growth of estrogen receptor-negative invasive breast carcinoma and requires BRCA1. Oncogene. 2009;28:843–853. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou BP, et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yook JI, Li XY, Ota I, Fearon ER, Weiss SJ. Wnt-dependent regulation of the E-cadherin repressor snail. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11740–11748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yook JI, et al. A Wnt-Axin2-GSK3beta cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacPherson MR, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 11 and serine 92 as new positive regulators of human Snail1 function: Potential involvement of casein kinase-2 and the cAMP-activated kinase protein kinase A. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:244–253. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu C, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of protein stability by GSK3 mediated phosphorylation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4032–4039. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domínguez D, et al. Phosphorylation regulates the subcellular location and activity of the snail transcriptional repressor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5078–5089. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.5078-5089.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldar-Finkelman H, Martinez A. GSK-3 Inhibitors: Preclinical and Clinical Focus on CNS. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:32 (abstr). doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: Tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viñas-Castells R, et al. The hypoxia-controlled FBXL14 ubiquitin ligase targets SNAIL1 for proteasome degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3794–3805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ota I, Li XY, Hu Y, Weiss SJ. Induction of a MT1-MMP and MT2-MMP-dependent basement membrane transmigration program in cancer cells by Snail1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20318–20323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910962106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong ZT, et al. EZH2 supports nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with HDAC1/HDAC2 and Snail to inhibit E-cadherin. Oncogene. 2012;31:583–594. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin T, Ponn A, Hu X, Law BK, Lu J. Requirement of the histone demethylase LSD1 in Snai1-mediated transcriptional repression during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2010;29:4896–4904. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y, et al. The SNAG domain of Snail1 functions as a molecular hook for recruiting lysine-specific demethylase 1. EMBO J. 2010;29:1803–1816. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, et al. LSD1 is a subunit of the NuRD complex and targets the metastasis programs in breast cancer. Cell. 2009;138:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe N, et al. M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFbeta-TrCP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarrió D, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer relates to the basal-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68:989–997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taube JH, et al. Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15449–15454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Y, Chu A, Turker MS, Glazer PM. Hypoxia-induced epigenetic regulation and silencing of the BRCA1 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3339–3350. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01121-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert PM, et al. HOXA9 regulates BRCA1 expression to modulate human breast tumor phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1535–1550. doi: 10.1172/JCI39534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo D, Wang J, Li J, Post M. Mouse snail is a target gene for HIF. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:234–245. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim S, et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) is highly expressed in ER-negative breast cancers and a biomarker predicting aggressive biology. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:512–520. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayyanathan K, et al. The Ajuba LIM domain protein is a corepressor for SNAG domain mediated repression and participates in nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9097–9106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geradts J, et al. Nuclear Snail1 and nuclear ZEB1 protein expression in invasive and intraductal human breast carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1125–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu Q, et al. BRCA1 tumour suppression occurs via heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Nature. 2011;477:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coene ED, et al. A novel role for BRCA1 in regulating breast cancer cell spreading and motility. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:497–512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripathi MK, et al. Regulation of BRCA2 gene expression by the SLUG repressor protein in human breast cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17163–17171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501375200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang SP, et al. p53 controls cancer cell invasion by inducing the MDM2-mediated degradation of Slug. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:694–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim NH, et al. p53 and microRNA-34 are suppressors of canonical Wnt signaling. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra71. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim NH, et al. A p53/miRNA-34 axis regulates Snail1-dependent cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:417–433. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.