Abstract

Juvenile hormone (JH) governs a great diversity of processes in insect development and reproduction. It plays a critical role in controlling the gonadotrophic cycles of female mosquitoes by preparing tissues for blood digestion and egg development. Here, we show that in female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes JH III control of gene expression is mediated by a heterodimer of two bHLH-PAS proteins—the JH receptor methoprene-tolerant (MET) and Cycle (CYC, AAEL002049). We identified Aedes CYC as a MET-interacting protein using yeast two-hybrid screening. Binding of CYC and MET required the presence of JH III. In newly eclosed female mosquitoes, the expression of two JH-responsive genes, Kr-h1 and Hairy, was dependent on both the ratio of light to dark periods and JH III. Their expression was compromised by in vivo RNA interference (RNAi) depletions of CYC, MET, and the steroid receptor coactivator SRC/FISC. Moreover, JH III was not effective in induction of Kr-h1 and Hairy gene expression in vitro in fat bodies of female mosquitoes with RNAi-depleted CYC, MET or SRC/FISC. A sequence containing an E-box–like motif from the Aedes Kr-h1 gene promoter specifically interacted with a protein complex, which included MET and CYC from the female mosquito fat body nuclear extract. These results indicate that a MET/CYC heterodimer mediates JH III activation of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes in the context of light-dependent circadian regulation in female mosquitoes during posteclosion development. This study provides an important insight into the understanding of the molecular basis of JH action.

Keywords: hormone receptor, insect hormone, transcriptional control

Mosquitoes serve as vectors of harmful human diseases because blood feeding is required for their egg development; disease pathogens use hematophagous female mosquitoes for obligatory stages of their life cycles. An insect-specific sesquiterpenoid juvenile hormone III (JH III) is essential for a newly eclosed female mosquito to reach a competence stage for blood feeding and egg maturation (1, 2). Although several aspects of the JH III–dependent development have been characterized (3–6), our understanding of molecular mechanisms underlying JH regulation of female mosquito posteclosion development is limited.

Methoprene-tolerant (MET), which is a basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH)-Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) protein, was discovered in Drosophila melanogaster (7), and its role in mediating a JH response has been established (8). MET binds to JH with a high affinity, suggesting that it is the JH receptor (9, 10). As a bHLH protein, MET requires either a homo- or heterodimer partner for its activity (11). Studies in Aedes aegypti, the beetle Tribolium castaneum, and the silkworm Bombyx mori have shown a bHLH-PAS domain-containing steroid receptor coactivator (SRC/FISC/Taiman) to interact with MET (10, 12–14). Whether, an additional bHLH transcription factor with DNA-binding properties is required as a Met partner remains to be established.

Using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening, we identified an Aedes ortholog of Drosophila cycle (CYC) as a JH-dependent heterodimeric partner of MET. In Drosophila, CYC is a bHLH-PAS protein that plays a central role in regulating circadian rhythms via heterodimerization with another bHLH-PAS protein Clock (CLK) (15). In Aedes female mosquitoes, depletion of either CYC or MET by means of RNA interference (RNAi) impaired the circadian activation of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes. Moreover, JH III was not effective in induction of Kr-h1 and Hairy gene expression in vitro in the fat body of female mosquitoes with RNAi-depleted CYC, MET, or SRC/FISC in contrast to wild-type and control RNAi mosquitoes. We provide evidence that the Met/CYC heterodimer specifically binds to a sequence containing the E-box–like motif in the regulatory region of the Kr-h1 gene. These results indicate that the MET/CYC/FISC heterodimer mediates JH III regulation of circadian gene expression in the mosquito A. aegypti and provide an important insight into the mode of action of this key insect hormone.

Results

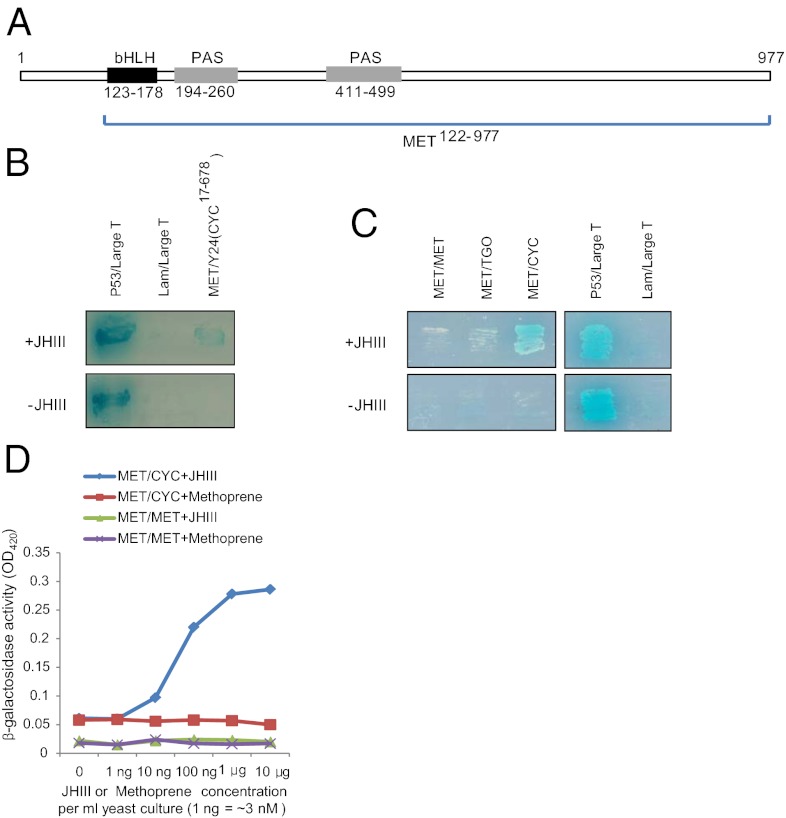

CYC Is a JH III-Dependent, MET-Interacting Protein in A. aegypti Female Mosquitoes.

To find a putative partner of MET in the mosquito A. aegypti, we used the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) library screening system. We constructed the bait plasmid containing Aedes MET122–977 that included the bHLH, PAS-A, and PAS-B domains and the 477-long C-terminal region (Fig. 1A). A prey library was prepared from mRNA isolated from A. aegypti female mosquitoes, 1–2 d PE. When we screened the library with the MET122–977 bait plasmid in the presence of JH III, we isolated a clone (Y24) that matched the AAEL002049 gene in the A. aegypti genome annotation that encodes CYC (Fig. 1B). The annotated Aedes CYC in the VectorBase lacked the N-terminal portion; therefore, we cloned full-length cDNA (cDNA) by rapid amplification of both cDNA ends, followed by DNA sequencing. The full-length cDNA of 3,122 nucleotides encoded a 744 amino acid-containing protein, which had 90 additional amino acids at its N-terminal compared with the genome annotated AAEL002049-PA (CYC91–744) protein (Fig. S1). The Y24 clone included a mosquito cDNA sequence that encoded a partial CYC protein of A17 to I678 (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

CYC binds to MET in a JH III-dependent manner. (A) Schematic diagram of MET used to construct yeast bait. MET122–977 contained bHLH, PAS-A and PAS-B domains, and the full C-terminal region. (B) A MET-binding Y2H clone (Y24) encodes A. aegypti CYC. JH III (10 μg/mL) was necessary for the growth of the yeast clone. (C) Full-length CYC specifically bound to MET in the presence of 10 μg/mL JH III. No significant binding was observed between MET and MET in the presence of JH III (MET/MET). Aedes TGO bound to MET at the background level in the presence or absence of JH III (MET/TGO). In both B and C, the yeast colony transformed with pGBKT7-53 and pGADT7-T plasmids was used as a positive control. The two positive control plasmids were a fusion protein of GAL4 DNA-BD with murine p53 and a fusion of GAL4-AD with large T-antigen, respectively. Murine p53 and large T-antigen specifically bound to each other, irrespective of the presence of JH III (P53/Large T). For the negative control, pGBKT7-Lam expressing human lamin C was used in place of the pGBKT7-53 plasmid and to test its interaction with murine p53 as a control for fortuitous interactions. This control was negative under all conditions (Lam/Large T). (D) JH III, but not methoprene, mediated binding between MET and CYC in a dose-responsive manner. Measurements were performed by means of the quantitative yeast β-galactosidase assay.

We then tested the binding between Aedes MET122–977 and the full-length Aedes CYC1–744. As a control, we selected the Aedes ortholog of Drosophila Tango (TGO) and the vertebrate ARNT (11). Genome-annotated AAEL010343 encodes only TGO66–570. Therefore, we cloned the cDNA encoding the full-length ORF of Aedes TGO by means of 5′-RACE and RT-PCR (Fig. S2). The phylogenetic analysis revealed nine clusters of bHLH-PAS transcription factors from human, fruit fly, and the mosquito A. aegypti (Fig. S2). The mosquito MET forms a unique cluster together with Drosophila MET and Germ Cell Expressed. This MET cluster could be grouped with CLK, CYC, and TGO with high bootstrap value (936/1000) (Fig. S2). Both CYC and TGO belong to class II bHLH-PAS factors, as they have the closest evolutionary relationships with one another (Fig. S3).

Y2H binding tests of the prey MET122–977 with each of the bait proteins—MET, CYC, and TGO—were then conducted (Fig. 1C). In the selective growth media in the absence of JH III, MET122–977, CYC1–744, and TGO1–570 exhibited only a background binding to METET22–977. However, in the JH III-containing selective growth media, binding between MET122–977 and CYC1–744 complemented the growth of yeast cells in the double depletion of His and Ade (Fig. 1C). However, TGO1–570 showed only a background binding level to MET122–977 in the presence of JH III. Likewise, a MET/MET combination formed no homodimer, irrespective of the presence or absence of JH III (Fig. 1C).

Next, we established the effect of the ligand concentration on MET/CYC binding using the Y2H β-galactosidase assay in Y187 yeast cells. We evaluated the level of MET/CYC and Met/Met binding using the reporter β-galactosidase after the addition of either JH III or a JH analog, methoprene, to the yeast assay (Fig. 1D). Addition of JH III strongly induced binding between MET122–977 and CYC1–744 in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, methoprene did not enhance MET/CYC binding, even at the high concentration of 10 μg/mL of the yeast cell culture (∼30 μM) (Fig. 1D). MET-to-MET interaction was not detected in the presence of either JH III or methoprene (Fig. 1D).

We then confirmed the protein–protein interaction between MET and CYC using the tagged c-myc-MET122–977 and HA-CYC1–744 fusion proteins coexpressed in Drosophila S2 cells (Fig. S4). After coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) with the anti-c-myc antibody, HA-CYC1–744 was detected with anti-HA antibody as a co-IP product, demonstrating interaction between MET and CYC (Fig. S4A). The protein–protein interaction between MET and CYC in the Co-IP reaction did not require the presence of JH III. This difference with JH III-dependent MET and CYC binding in the Y2H system is not clear. Nevertheless, the co-IP experiment serves as a confirmation of MET/CYC interaction.

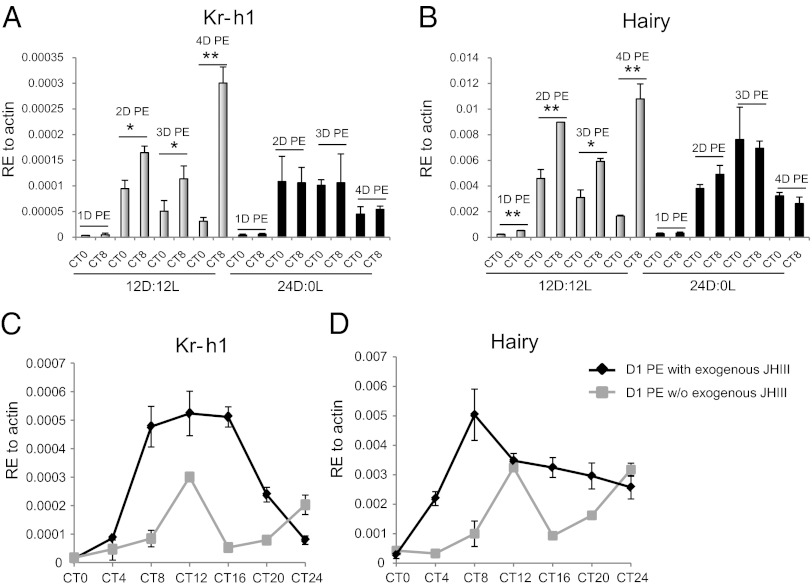

Expression of Kr-h1 and Hairy Genes Depends on Light–Dark Cycles in Newly Enclosed Female Mosquitoes.

The Drosophila Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) gene encodes a zinc-finger motif transcription factor, which has been implicated in larval–pupal metamorphosis (16). It is now used as a representative marker gene under the regulation of JH and MET (14, 17–19). The Hairy gene encodes a bHLH protein with an orange domain and C-terminal Groucho interacting motifs (20). Expression of Kr-h1 (AAEL002390) and Hairy (AAEL005480) genes is JH III-dependent during the PE development of A. aegypti female mosquitoes (17). When female mosquitoes were maintained under a 12-h dark/12-h light (12D:12L) cycles until 4 d (4D) PE, Kr-h1 and Hairy gene transcript abundance exhibited periodic fluctuations, increasing from circadian time 0 (CT0) to CT8 in each light–dark cycle (Fig. 2 A and B). The overall transcript levels of both genes reached a maximum at 4D PE, which is in accord with the JH III-mediated PE maturation of female mosquitoes that has been completed at this time. However, when PE female mosquitoes were maintained under constant dark (24D:0L) conditions, there were no significant differences in either Kr-h1 or Hairy gene expression at CT0 and CT8, and unlike those under the 12D:12L cycle (Fig. 2 A and B) the overall transcript levels of both Kr-h1 and Hairy genes did not increase by 4D PE.

Fig. 2.

Circadian- and JH-dependent expression of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes. Kr-h1 (A) and Hairy (B) genes showed the circadian rhythmic pattern of gene expression when mosquitoes were kept under a 12 h dark–12 h light (12D:12L) cycle, with a higher expression level at circadian time 8 (CT8) than CT0 on each day. Overall, expression levels of both genes reached maximum at 4D PE. This circadian expression was not observed in the mosquitoes kept in constant darkness (24D:0L) and transcripts remains low at 4D PE. (C and D) Female mosquitoes 1-d PE were collected at CT0, the transition time from dark to light in a 12D:12L cycle, and each mosquito was treated with 0.2 μL of either 1 μg/mL JH III in acetone solution or acetone only. RNA samples were isolated at 4-h intervals until CT24 (same time point as CT0 2D PE) and applied to qPCR for quantifying the gene expression of Kr-h1 (C) and Hairy (D). Statistical significance between samples was evaluated using the Student t test (GraphPad 5.0).

We investigated whether the light/dark-dependent expression of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes was JH III-dependent. We analyzed the expression of these JH-dependent genes in newly emerged female mosquitoes (1-d PE) because their endogenous JH levels were reportedly low during this period (21). Female mosquitoes 1-d PE were treated with a 0.2-μL topical application of either 1 μg/mL JH III in acetone solution or a solvent (acetone) in the early morning (CT0), the time of the transition from dark to light, and then maintained on sugar solution until next morning (CT24). Total RNA was collected at 4-h intervals, and transcript abundance of Kr-h1 and Hairy was determined using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Expression profiles of these genes in solvent-treated mosquitoes were similar, peaking at CT12, declining to the basal level by CT16, and rising again by CT24 (Fig. 2 C and D). Topical treatment with exogenous JH III resulted in an enhanced abundance of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts within several hours; the levels of both transcripts were considerably higher in JH III-treated female mosquitoes than in those treated with a solvent (Fig. 2 C and D). The Kr-h1 transcript level exhibited a bell-shaped curve, peaking at CT12 and returning to a background level by CT24 (Fig. 2C). In the same JH III-treated mosquitoes, Hairy transcript level peaked at CT8, maintaining high level of expression until CT20 (Fig. 2D).

Northern blot analysis confirmed our qPCR data that Kr-h1 expression depends on the light/dark cycle and is strongly enhanced by the application of exogenous JH III (Fig. S4B). At the same time, CYC and MET transcripts exhibited no enhancement from application of exogenous JH III, but their transcript abundance gradually increased by CT24 (Fig. S4). Expression of PER, by the exogenous JH III (Fig. S4B).

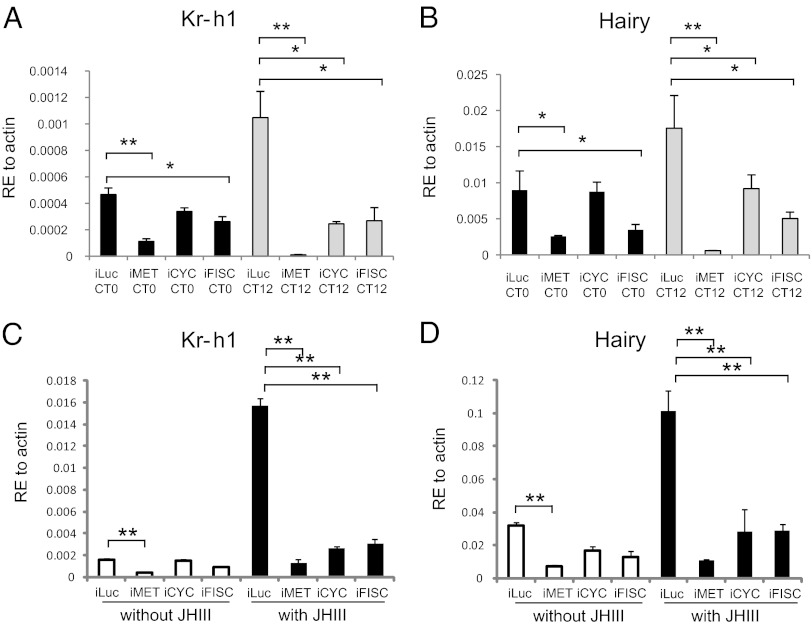

MET, CYC, and FISC Mediate JH III Control of Expression of Kr-h1 and Hairy.

We then tested effects of RNAi depletions of CYC, MET, and FISC on the abundance of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts (Fig. 3 A and B). Efficiency of RNAi for each factor is presented in Fig. S5A. In the control iLuc mosquitoes, the level of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts at CT12 increased compared with CT0, which is in an agreement with the circadian-mediated PE expression of these genes. In contrast, depletion of CYC resulted in a significant decrease of the abundance of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts at CT12, although it did not markedly reduce the expression of these genes at CT0 (Fig. 3 A and B). Depletions of MET and FISC lowered transcript levels of both genes at CT0 and CT12. These results indicate that CYC, MET, and FISC are required for circadian regulation of JH-dependent Kr-h1 and Hairy genes. However, MET and FISC are also needed for expression of these genes irrespective of light/dark cycles (Fig. 3 A and B). RNAi CLK depletion did affect expression of neither Kr-h1 nor Hairy, suggesting that the CLK/CYC/PER circuit was not directly involved in the JH III-dependent regulation of Kr-h1 and Hairy (Fig. S5B).

Fig. 3.

MET, CYC, and FISC are required for the circadian activation of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes. RNAi depletion of CYC (iCYC), MET (iMET), or FISC (iFISC) compromised the circadian activation of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes in fat bodies of Aedes female mosquitoes. After injection of iMET, iCYC, iFISC, and control dsRNA (iLuc) into the newly emerged female mosquitoes (1-d PE), they were subjected to a 12D:12L cycle for 4 d. Total RNA from these 5D PE mosquitoes was extracted at CT0 and CT12 and subjected to qPCR analysis using either Kr-h1 or Hairy gene-specific primers. (C and D) Four days after dsRNA injection of iMET, iCYC, iFISC, or control iLuc into 1 PE-old Aedes female mosquitoes, fat bodies were dissected and incubated in in vitro culture medium either in the presence of 1 μg/mL JH III or solvent (acetone). RNA samples were isolated 6 h after incubation and the levels transcripts were quantified by means of qPCR for Kr-h1 (C) and Hairy (D). Each result represents an average of three biologically independent repeats. Results were normalized against the β-actin transcript. In all experiments, each time point represents an average of three biologically independent repeats. Statistical significance between samples was evaluated using the Student t test (GraphPad 5.0).

An in vivo RNAi depletion is systemic and cannot completely rule out a possibility of an indirect effect on circadian regulation of JH-dependent Kr-h1 and Hairy genes. Therefore, we conducted in vitro experiments to determine the effect of RNAi depletions of MET, CYC, and FISC on JH III-dependent level of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts. Fat bodies from female mosquitoes 4D after double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) treatments were dissected and incubated in the complete culture medium supplemented with either JH III or solvent (acetone). The level of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts was equally low in fat bodies from all dsRNA treatments after incubation in the culture medium with acetone. In fat bodies from iLuc control mosquitoes, the levels of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts highly increased in the presence of JH III (Fig. 3 C and D). In contrast, there was no such a JH III-mediated elevation of the level of Kr-h1 and Hairy transcripts in fat bodies from females mosquitoes with RNAi depletions of MET, CYC, and FISC (Fig. 3 C and D), clearly showing that these factors are involved in JH-dependent regulation of circadian expression of Kr-h1 and Hairy genes.

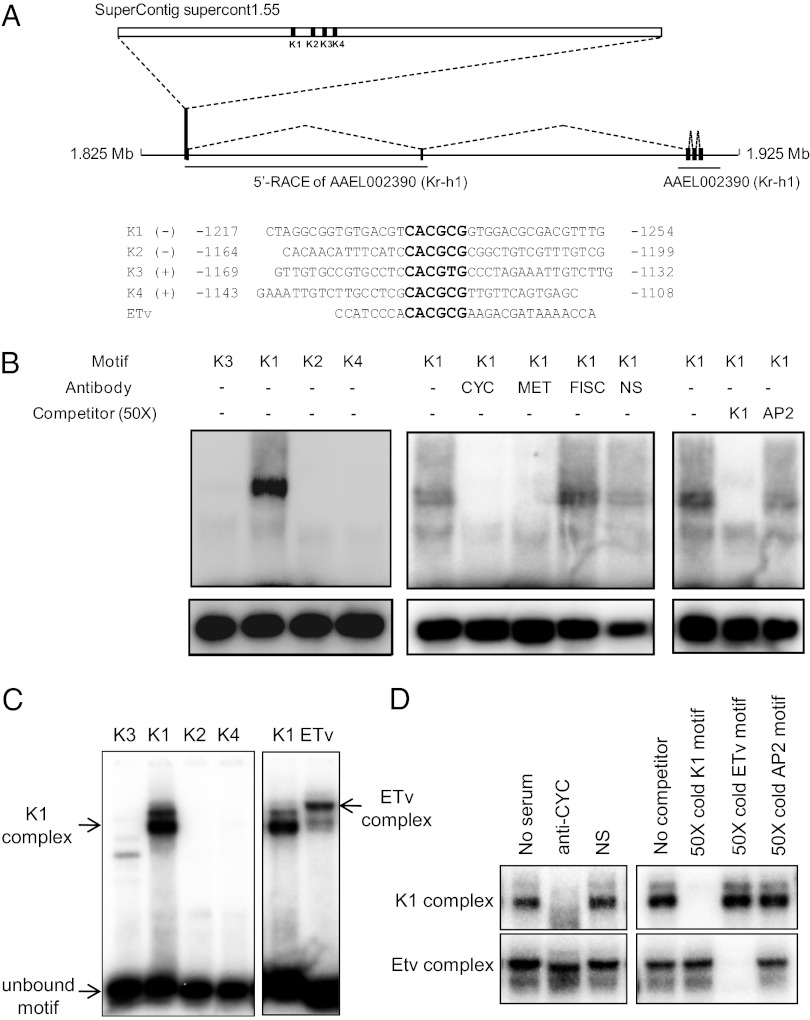

MET and CYC Bind to a Sequence Containing an E-Box–Like Motif from the Kr-h1 Gene Promoter.

The gene encoding Kr-h1 factor (AAEL002390) has been annotated in the A. aegypti genome. In this study, we identified two additional exons encoding 5′-UTR of Kr-h1 by means of 5′-RACE PCR (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6). As a result, we predicted a putative promoter located about 85-kb upstream from the annotated Kr-h1 gene. It harbored four tandem motifs, designated as K1, K2, K3, and K4, with core sequences resembling E-box sites (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6). The motif K3 had “T” in a position 5, whereas other sequences had “C.” This motif K3 was similar to a recently reported MET-interacting from B. mori (14), whereas K1, K2, and K4 “CACGCG” motifs were similar to a MET-binding sequence (ETv) from the JH III-regulated Aedes gut-specific early trypsin (ET) gene (Fig. 4A) (12).

Fig. 4.

Binding of CYC and MET to the E-box-like motif from the Kr-h1 gene promoter. (A) A map of the 2-kb of 5′ regulatory region of the Kr-h1 gene. It was cloned by means of 5′-RACE PCR based on the nucleotide sequence of AAEL002390 (Kr-h1). It harbored three imperfect E-box-like (CACGCG) motifs—K1, K2, and K4—and a single K3 CACGTG motif. E-box–like motifs (indicated in bold) and their flanking sequences, used for gel mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments (B), are indicated. (B) The EMSA revealed the presence of a DNA–protein complex between the Kr-h1 K1 sequence and the nuclear extract from fat bodies of female mosquitoes (left panel). The presence of MET and CYC, but not FISC, in the DNA–protein complex was confirmed by adding polyclonal antibodies against each of these proteins to the binding reactions (center panel). NS – nonspecific serum control. For competition tests (Right), a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe or a nonspecific double-stranded oligonucleotide (AP2) was added to the binding mixtures. (C and D) Gel mobility shift assay using nuclear extracts from Schneider Drosophila S2 cells. (C) The assay revealed the presence of a DNA–protein complex between the Kr-h1 K1 sequence and the nuclear extract from Schneider Drosophila S2 cells (Left). This K1 complex shows a different mobility from that of the complex, formed by binding between the ETv motif and the nuclear extract (Right). (D) The presence of CYC in the Kr-h1 K1 complex, but not in the ETv complex, was confirmed by adding polyclonal antibody against Drosophila CYC to the binding reactions (Left). For competition tests (Right), an ∼50-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe or a nonspecific double-stranded oligonucleotide (AP2) was added to the binding mixtures.

We used the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to evaluate binding properties of these four Kr-h1 promoter sequences. When we tested binding between each of these sequences and the nuclear extract collected from fat bodies of female mosquitoes 2D PE, only the K1 sequence formed a dense band (Fig. 4B, left). There was interference in formation of this complex when we added the antibodies against either Aedes MET or Drosophila CYC, indicating that both MET and CYC were components of this DNA–protein complex (Fig. 4B, Center). However, the addition of Aedes FISC antibody did not affect the formation of the complex, suggesting that FISC was not in the complex under these conditions (Fig. 4B, Center). Addition of a nonspecific serum had a weak effect on the formation of the complex. Binding specificity was confirmed by competition with the 50-fold excess of unlabeled K1 probe, which eliminated the K1 complex. In contrast, addition of the 50-fold excess of unlabeled nonspecific probe (AP2) had little effect (Fig. 4B, Right).

The EMSA between the nuclear extract from Drosophila Schneider L2 cells and the Kr-h1 promoter sequences K1–K4 confirmed the results. Only the K1 sequence formed a specific binding complex (Fig. 4C, Left). Formation of the complex was affected by addition of Drosophila anti-CYC antibodies, suggesting that CYC is one of the components of the binding complex with the Aedes Kr-h1 K1 sequence (Fig. 4D, Left Upper). The specificity of the K1 complex was confirmed by competition with the 50-fold excess of unlabeled K1 probe, which eliminated the K1 complex. In contrast, addition of 50-fold excess of unlabeled AP2 nonspecific probe had no effect (Fig. 4D, Right Upper).

The mobility of the ETv complex in the EMSA assay with the nuclear extract from Drosophila Schneider L2 cells was dissimilar from that of the K1 complex, suggesting that the compositions of these complexes are different (Fig. 4C, Right). The mobility of the ETv complex was not affected by the addition of the anti-CYC antibodies, indicating that CYC was not a part of the ETv complex (Fig. 4D, Left Lower). Moreover, addition of the 50-fold excess of either unlabeled K1 or ETv probes displaced only their respective complexes (Fig. 4D, Left).

Discussion

The bHLH-PAS transcription factors function as obligatory dimers, mainly as heterodimers, binding DNA at specific promoter elements and recruiting cofactors (11). DNA-binding properties of bHLH-PAS transcription factors are determined by the bHLH domains located in their N-termini, whereas their PAS domains are essential for dimerization (11, 22). The PAS domains of bHLH-PAS transcription factors are also essential for recruitment of cofactors, including bHLH-PAS NCoA/SRC coactivators (22). The JH receptor MET recruits a bHLH-PAS nuclear transcriptional coactivator SRC/FISC for JH-activated gene expression (10, 12–14). Similar to other bHLH-PAS proteins, MET contains two PAS domains, PAS-A and PAS-B (10, 12). The PAS-B domain of MET is necessary and sufficient for JH III binding (10). It is also adequate for dimerization of Tribolium MET with SRC (10). However, both PAS-A and PAS-B domains are needed for MET interaction with SRC/FISC in A. aegypti (12). Thus, these studies have demonstrated that MET possesses functions characteristic of members of the bHLH-PAS transcription factor family by being capable of recruiting coactivators and additional transcription factors to initiate a ligand-mediated gene expression. However, whether MET heterodimerizes with another DNA-binding bHLH-PAS transcription factor within the JH receptor complex has remained unclear.

Here, we report identification of Aedes CYC as a JH III-dependent MET-interacting protein based on Y2H screening of the library prepared from female mosquitoes during JH-mediated PE. In direct Y2H tests, MET bound CYC only in the presence of JH III. This protein–protein interaction was additionally confirmed by means of Co-IP of these proteins expressed with specific tags. We detected no such interaction for MET/MET in Y2H tests, irrespective of the presence or absence of JH III. Similar to the vertebrate bHLH-PAS transcription factor ARNT (HIF-beta), its Drosophila ortholog, TGO, serves as a partner for several bHLH-PAS transcription factors (11, 22, 23). However, we found no interaction between Aedes TGO and MET under the screening and assaying conditions we used in this study.

Using Y2H β-galactosidase reporter experiments, we showed that JH III–induced binding between MET and CYC in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, methoprene did not enhance MET/CYC interaction, even at the high concentration. We used Aedes MET122–977 rather than Met1–596 (12). The long C-terminal of MET used in our construct could contribute to the specificity of JH III binding to the heterodimers MET/CYC. Despite extensive studies of bHLH-PAS transcription factors, there is still much to learn about the functional significance of their long C-termini (22). The glutamine-rich C-terminal domain, C-TAD, of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) recruits several coactivators, including CBP/p300 (22). Further studies are required to understand the functional role of the Met C-terminal region.

A composition of the MET DNA-binding complex was further investigated using EMSA to analyze the nuclear extract collected from fat bodies of female mosquitoes PE. In this EMSA screening, a specific band was formed with the K1 sequence containing an E-box–like motif from the JH-regulated Kr-h1 gene. Addition of antibodies against either Aedes MET or Drosophila CYC resulted in displacement of the band, indicating that both Met and CYC are components of this MET DNA-binding protein complex. When using EMSA to analyze Drosophila cell line nuclear extracts, both the K1 sequence from the JH-regulated Kr-h1 gene and the Etv sequence from Aedes ET gene formed specific bands, although of different mobility. Significantly, Drosophila CYC antibody effectively displaced the K1 sequence-protein complex but had no effect on mobility of the Etv sequence-protein band. The latter experiments suggest that CYC is not a component of a DNA-binding complex forming with the Etv sequence from the Aedes gut-specific ET gene. The K1 sequence from Aedes Kr-h1 gene that bound MET/CYC contained a core sequence resembling imperfect E-box site. The E-box motif with a consensus CANNTG is a characteristic signature for recognition binding sites in genes regulated by bHLH-PAS transcription factors (22, 23). However, this K1 motif “CACGCG” had C in a position 5 that was similar to a MET-binding sequence ETv from the JH III-regulated Aedes ET gene (12). A recently reported MET-interacting site from B. mori had T in a position 5 (14). Further large-scale bioinformatics analyses are required to develop a unified consensus for MET binding sites in insect genes.

We have shown here that, in A. aegypti female mosquitoes, expression of JH-dependent Kr-h1 and Hairy genes requires light/dark daily rhythms and oscillated, gradually rising to the maximal level by the fourth day of PE development. Genome-wide profiling of PE females of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae has demonstrated that at least 16% of genes with various biological functions are under light/dark rhythm control (24). However, whether JH III is involved in this in Aedes mosquitoes has not been identified. In this work, we showed that CYC, MET, and the SRC coactivator FISC are required for the JH-mediated regulation of circadian expression in the female mosquito PE. Deciphering the precise cross talk between the JH-mediated regulation of circadian gene expression and the circadian clock molecular machinery represents an exciting goal for the future research.

Our study provides an important insight into the understanding of the molecular basis of JH action. It implies that the JH receptor is a heterodimer of two DNA-binding bHLH-PAS transcription factors, with MET as its obligatory component. We suggest that MET is capable of recruiting different DNA-binding bHLH-PAS partners in a context of various sex-, stage-, tissue-, cell-, and gene-specific conditions. JH is an insect-specific hormone responsible for a plethora of functions and processes (25). The ability of the JH receptor MET to heterodimerize with different partners is likely a key to the pleiotropic action of its ligand. Future research should explore this important hypothesis.

Methods

Experimental Animals.

The UGAL/Rockefeller strain of A. aegypti mosquitoes was maintained in the laboratory as described previously (26). Adult mosquitoes were provided with water and a 10% sucrose solution. To initiate egg development, mosquitoes were blood fed on white rats. The University of California at Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures for use of vertebrate animals.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening and Binding Tests.

A bait plasmid was constructed by introducing the cDNA fragment encoding MET122–977 into the GAL4 DNA-binding domain of the vector pGBKT7 (Clontech). A GAL4-AD fusion library from mosquitoes 1–2D PE was constructed using the Matchmaker Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Library Construction and Screening Kit (Clontech). Y187 yeast cells harboring the library of prey plasmids were mated to Y2HGold yeast strain transformed with pGBKT7-MET122–977, and the binding was tested in the medium of synthetic dropout (SD)-Leu/-Trp/-His supplemented with X-α-gal, Aureobasidin A, and 10 μg/mL JH III. For detection of protein–protein interaction, the cDNA fragments encoding MET122–977, CYC1–744, and TGO1–570 were cloned into the GAL4 DNA-activation domain vector pGADT7 and used as prey plasmids with the bait MET122–977. For quantitative Y2H β-galactosidase tests, the prey plasmids containing MET122–977 or CYC1–744 were transformed together with the MET122–977 bait plasmid into the Y187 yeast strain. The transformed yeast cells were incubated overnight at 30 °C in the medium of SD-Leu/-Trp, and then harvested, suspended, and distributed into 1 mL SD-Leu/-Trp medium at the concentration of OD600 = 0.5. Corresponding concentrations of JH III or methoprene were added into the growth medium and the cells were incubated further for 2 h and applied to the quantitative β-galactosidase assay using a Yeast β-Galactosidase Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).

Molecular Cloning.

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) was performed using the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech) to obtain the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA sequences of A. aegypti CYC and TGO; 5′-end of cDNA sequence of A. aegypti Kr-h1 was also obtained by RACE. Reverse transcription was carried out using an Omniscript reverse-transcriptase kit (Qiagen) with oligo (dT) primers. PCR was performed using Platinum High Fidelity Supermix (Invitrogen). Primer sequences used for molecular cloning are shown in SI Methods.

RNAi Approach.

For RNAi-mediated depletion, dsRNAs were synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase. Synthesis of dsRNAs was accomplished by simultaneous transcription of both strands of template DNA using the MEGAscript kit (Ambion). A Picospritzer II (General Valve) was used to introduce dsRNA into the thorax of CO2-anesthetized mosquito females at 1–2 D PE. Mosquitoes were assayed 4D after dsRNA injections. Mosquitoes injected with luciferase dsRNA (iLuc) served as controls. The knockdown of a specific transcript was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. S5). Primers used for amplification are indicated in SI Methods.

RNA Preparation, Northern Analyses, and Real-Time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol (GIBCO/BRL). For Northern blotting, 5 μg of total RNA from each sample was separated on a formaldehyde gel, blotted, and hybridized with the corresponding 32P-labeled DNA probe. Real-time RT-PCR experiments were performed, as described previously (26). Primers for real-time RT-PCR are listed in SI Text.

In Vitro Fat Body Culture.

The in vitro fat body culture experiments were performed as described previously (26). Fat bodies were dissected 4D after dsRNA injections of Aedes female mosquitoes. These fat bodies were incubated for 6 h in a complete culture medium supplemented with either 1 μg/mL JH III or a solvent (acetone). Incubation plate wells were siliconized before incubation with JH to prevent its absorption by plastic.

EMSA.

The annealed deoxyoligonucleotide of each E-box–like motif was purified from 15% TBE Criterion Precast Gel (Bio-Rad). Double-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled by γ-32P ATP. EMSA was performed using a gel-shift assay system (Promega) with the nuclear extract of the fat body of 1- to 2-d-old mosquitoes or one of Drosophila Schneider S2 cells (Active motif). The DNA–protein complex was separated on 5% TBE Criterion Precast Gel (Bio-Rad) and visualized by means of autoradiography. For competition assay, 50-fold unlabeled E-box–like motif or unlabeled AP-2 motif was incubated with the nuclear extract for 10 min and then further incubated with labeled motif for 20 min. Identity of the complex was verified by directly adding polyclonal antibodies against A. aegypti MET (a gift from Jinsong Zhu, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA), Drosophila CYC (Abcam), or A. aegypti FISC to the binding reactions.

Co-IP in Drosophila S2 Cell Line.

Complementary DNAs encoding A. aegypti MET122–977 or CYC1–744 were amplified by means of PCR, inserted into pAC5.1/V5/HisA vector (Invitrogen) with a specific 5′-terminal tag (c-myc for MET and HA for CYC). These two plasmids were transfected separately or together in Drosophila S2 cells. After 36 h of incubation, cells were harvested, washed twice with 1× PBS (PBS), and lysed on ice for 1 h in a lysis buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 100 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with 1 mM DTT, complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), and phosphatase inhibitor mixture 1 (Sigma). Lysates from these three samples were collected by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and treated with anti-c-myc mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam), which was followed by precipitation with Protein-G-agarose (Protein G Immunoprecipitation Kit, Roche). The precipitated samples were subjected to Western blotting with anti-HA rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam). For input controls, c-myc-MET and HA-CYC are transfected separately or together in Drosophila S2 cells and detected by Western blotting with either anti-HA rabbit polyclonal or anti-c-myc mouse monoclonal antibodies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jinsong Zhu for the generous gift of Aedes anti-MET antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Award 2R01AI036959 to A.S.R.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database [accession nos. JN573265 (CYC) and JN573266 (TGO)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1214209109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Clements AN. 1992. The biology of mosquitoes. Development, Nutrition and Reproduction (Chapman & Hall, London), Vol 1.

- 2.Raikhel AS, et al. Molecular biology of mosquito vitellogenesis: from basic studies to genetic engineering of antipathogen immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1275–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwadz RW, Spielman A. Corpus allatum control of ovarian development in Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1973;19:1441–1448. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(73)90174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raikhel AS, Lea AO. Hormone-mediated formation of the endocytic complex in mosquito oocytes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1985;57:422–433. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(85)90224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raikhel AS, Lea AO. Juvenile hormone controls previtellogenic proliferation of ribosomal RNA in the mosquito fat body. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1990;77:423–434. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(90)90233-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu J, Chen L, Raikhel AS. Posttranscriptional control of the competence factor betaFTZ-F1 by juvenile hormone in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13338–13343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234416100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashok M, Turner C, Wilson TG. Insect juvenile hormone resistance gene homology with the bHLH-PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2761–2766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konopova B, Jindra M. Juvenile hormone resistance gene Methoprene-tolerant controls entry into metamorphosis in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10488–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703719104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miura K, Oda M, Makita S, Chinzei Y. Characterization of the Drosophila Methoprene -tolerant gene product. Juvenile hormone binding and ligand-dependent gene regulation. FEBS J. 2005;272:1169–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles JP, et al. Ligand-binding properties of a juvenile hormone receptor, Methoprene-tolerant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21128–21133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116123109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kewley RJ, Whitelaw ML, Chapman-Smith A. The mammalian basic helix-loop-helix/PAS family of transcriptional regulators. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:189–204. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Mead EA, Zhu J. Heterodimer of two bHLH-PAS proteins mediates juvenile hormone-induced gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:638–643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013914108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Xu J, Sheng Z, Sui Y, Palli SR. Steroid receptor co-activator is required for juvenile hormone signal transduction through a bHLH-PAS transcription factor, methoprene tolerant. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8437–8447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayukawa T, et al. Transcriptional regulation of juvenile hormone-mediated induction of Kruppel homolog 1, a repressor of insect metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11729–11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204951109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardin PE. Essential and expendable features of the circadian timekeeping mechanism. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecasse F, Beck Y, Ruiz C, Richards G. Krüppel-homolog, a stage-specific modulator of the prepupal ecdysone response, is essential for Drosophila metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2000;221:53–67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, Busche JM, Zhang X. Identification of juvenile hormone target genes in the adult female mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minakuchi C, Zhou X, Riddiford LM. Krüppel homolog 1 (Kr-h1) mediates juvenile hormone action during metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Dev. 2008;125:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minakuchi C, Namiki T, Shinoda T. Krüppel homolog 1, an early juvenile hormone-response gene downstream of Methoprene-tolerant, mediates its anti-metamorphic action in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev Biol. 2009;325:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastwood K, Yin C, Bandyopadhyay M, Bidwai A. New insights into the Orange domain of E(spl)-M8, and the roles of the C-terminal domain in autoinhibition and Groucho recruitment. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;356:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0996-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro AB, et al. Juvenile hormone and juvenile hormone esterase in adult females of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1986;32:867–877. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partch CL, Gardner KH. Coactivator recruitment: a new role for PAS domains in transcriptional regulation by the bHLH-PAS family. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:553–557. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson HI, Chan WK, Bradfield CA. DNA binding specificites and pairing rules of the Ah receptor, ARNT, and SIM proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20292–26302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rund SS, Hou TY, Ward SM, Collins FH, Duffield GE. Genome-wide profiling of diel and circadian gene expression in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E421–E430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100584108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flatt T, Tu MP, Tatar M. Hormonal pleiotropy and the juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila development and life history. Bioessays. 2005;27:999–1010. doi: 10.1002/bies.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy SG, Hansen IA, Raikhel AS. Effect of insulin and 20-hydroxyecdysone in the fat body of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.