Abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA (LAMP) is a powerful isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique that can accumulate ~109 copies from less than 10 copies of input template within an hour or two. Unfortunately, while the amplification reactions are extremely powerful, the quantitative detection of LAMP products is still analytically difficult. In this article, in order to both improve the specificity of LAMP detection and to make direct readout of LAMP amplification simpler and much more reliable, we have developed a non-enzymatic nucleic acid circuit (catalyzed hairpin assembly, CHA) that can both amplify and integrate the specific sequence signals present in LAMP amplicons. Through a hairpin acceptor, one of the four loop products amplified from the LAMP is transduced to an active catalyst ssDNA which can in turn trigger a CHA reaction. After CHA detection, even less than 10 molecules/μL model templates (M13mp18) can produce significant signal, and both non-specific template and parasitic amplicons cannot bring interference at all. More importantly, to further enhance the specificity, we have designed a dual-CHA circuit that only gave positive responses in presence of two LAMP loops. The AND-GATE detector will act as a simultaneous, specific readout of the LAMP product, rather than of competing and parasitic amplicons.

Keywords: LAMP, hairpin assembly, DNA circuit, amplification

INTRODUCTION

Signal generation and amplification plays a significant role in achieving sensitive detection of nucleic acids.1–5 To realize this aim, a series of very powerful isothermal nucleic acid amplification techniques have been developed that have shown promising applications in research, diagnostics, forensics, medicine, and agriculture.6,7 These techniques include self-sustained sequence replication (3SR8), nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA9), signal-mediated amplification of RNA technology (SMART10), strand displacement amplification (SDA11), isothermal multiple displacement amplification (IMDA12), helicase-dependent amplification (HDA13), single primer isothermal amplification (SPIA14), and loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA (LAMP15). Among these techniques, LAMP is especially interesting as it employs only one enzyme and is relatively insensitive to the secondary structure of the amplicon. LAMP relies on four specially designed primers that recognize a total of six distinct sequences on a double-stranded template (Figure 1 step I); these primers not only are extended but assist in destructuring the template. By using alternating extension and strand displacement reactions, the entire LAMP process can continuously yield long DNA concatamers. Its sensitivity is outstanding, as upwards of ~109 copies accumulate from less than 10 copies of input template within an hour or two.15–18 Unfortunately, while the amplification reactions are extremely powerful, the quantitative detection of LAMP products is still analytically difficult. In many cases, the final concatameric products are characterized by agrose gel electrophoresis 15. Limited quantitative results have been obtained by dye (ethidium bromide) staining 15,19, or by crudely monitoring the increase of either calcein fluorescence or solution turbidity due to the excessive release of pyrophosphate from nucleoside triphosphates20,21. Even though these methods allow real-time detection, the signals are due solely to the accumulation of base-pairs and can easily read false amplicons (molecular parasites) as true ones.22–24 Off-target amplicons are an especially pernicious problem for LAMP, in part because of its extraordinary ability to amplify small numbers of templates.

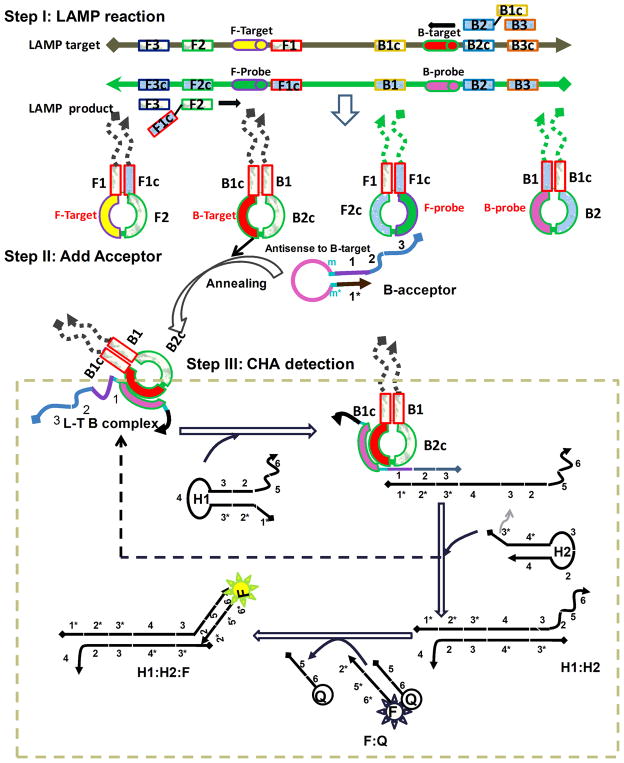

Figure 1.

Three-step scheme for DNA detection. Step I: LAMP reaction, which produces single-stranded loops. Step II: LAMP products anneal to the Acceptor, and the resultant conformational change yields a domain 1 toehold and a catalyst for CHA. Step III: CHA amplification and fluorescence detection.

Recently, more specific detection methods have been developed that probe the single strand loops at the termini of LAMP concatamers, including using AuNPs for colorimetric and electrochemical detection.25,26 However, these methods require relatively expensive reagents and devices, and are problematic for point-of-use or point-of-care diagnostics. Moreover, since there are relatively few loop structures in each concatamer, direct readout of the loops without amplification limits sensitivity.

In order to both improve the specificity of LAMP detection and to make direct readout of LAMP amplification simpler and much more reliable, we have developed a non-enzymatic nucleic acid circuit that can both amplify and integrate the specific sequence signals present in LAMP amplicons. As a result of the unique primers and mechanisms involved in LAMP, the amplicons include cauliflower-like structures with four types of single-stranded loops (Figure 1, Step I). Recently, we and others have developed non-enzymatic catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) reactions27–29 that are triggered by short, single-stranded nucleic acid (catalyst) inputs and that can be coupled to a variety of analytical outputs. We therefore sought to transduce the single-stranded loop regions from LAMP into CHA reporters. As shown in Figure 1, step II, one of the LAMP loops opened a hairpin (Acceptor) and in turn activated the single-stranded catalyst (sequence 3-2-1). The 3-2-1 could then further trigger downstream amplification by CHA and ultimately fluorescence detection. The fact that hybridization is required to open the hairpin Acceptor means that the LAMP reaction is being probed with high specificity, similar to a TaqMan probe. In addition, the high signal-to-background ratio of CHA guaranteed hundreds-of-fold additional signal amplification within a few hours. Using these methods we could detect less than 10 molecules/μL of a model target (here, M13mp18). Our adaptation of CHA to LAMP was especially useful for suppressing false-positive signals from parasitic amplicons, one of the key problems limiting the further development of LAMP as a technology. We further guaranteed the surety of signaling by using a dual-CHA circuit that only gave positive responses in the presence of both LAMP loops. This AND-GATE detector acts as a simultaneous, specific readout of the LAMP product, rather than of competing, parasitic amplicons. Finally, CHA is not only enzyme-free, but inherently modular and scalable. Thus, a previously optimized CHA circuit can be immediately adapted to new reactions based on the redesign of the intermediate Acceptor molecule without also redesigning the main circuitry or reporter constructs.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemicals and oligonucleotides

All chemicals were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated. All oligonucleotides were ordered from Integrated DNA Technology (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA). Oligonucleotide sequences are summarized in Table S1. Other than F and Q, all oligonucleotides were purified via denaturing PAGE (7 M Urea, 1x TBE), and concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. All oligonucleotides were stored as 10 μM stocks in H2O or 1x TE (pH 7.5) at −20°C. M13mp18 single-stranded DNA, lambda DNA, and 120,000 U/μL Bst polymerase large fragments were obtained from New England Biolabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA).

Standard LAMP reaction

Mixtures containing template, 0.8 μM each B1c-B2 and F1c-F2, 0.2 μM each B3 and F3, 1 M betaine, and 0.4 mM dNTPs in a total volume of 24 μL 1x ThermoPol Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 % Triton X-100, pH 8.8) were heated to 95°C for 5 to 10 min, followed by chilling on ice for 2 min. Then, 1 μL (120 U) of Bst polymerase large fragment was added to initiate the LAMP reaction. The reactions (with a final volume of 25 μL) were incubated at 65°C for 1 to 1.5 hours, followed by heating to 80°C for 10 min to denature the polymerase. In some control experiments, LAMP reactions were carried out without betaine. When necessary, 6 to 10 μL aliquots from the 25 μL LAMP reactions were resolved on a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Coupling LAMP to CHA and real-time fluorescence detection

A 10 μL aliquot of the 25 μL LAMP reaction was mixed with 1 μL of 500 nM B/F-Acceptor, followed by heating to 95°C for 5 min and slowly cooling to room temperature at a rate of 0.1°C/s. Some 5 μL of this mixture was further mixed with 5 μL of 200 nM H1, 5 μL of 1.6 μM H2, and 5 μL of Reporter duplex (containing 200 nM F and 400 nM Q) in TNaK Buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 140 mM NaCl; 1 μM (dT)21). H1 and H2 were separately refolded (90°C for 1 min, followed by cooling to room temperature at 0.1°C/s) in TNaK Buffer immediately before use. For each reaction, 18 μL of the final 20 μL reaction mixture was added to a well of a 384-well plate that had been pre-incubated at 37°C in a TECAN Safire plate reader. Fluorescence readings were immediately taken as a function of time.

For the experiment with molecular beacon reporters, 1 μL of 500 nM MB (instead of Acceptor) was added to 10 μL of LAMP reaction products. The mixtures were then heated to 90°C for 1 min and cooled down to room temperature at 0.1°C/s, after which 5 μL of the mixture was diluted with 15 μL TNaK Buffer, and fluorescence measurements were taken at 37°C in a 384-well plate using a TECAN Safire plate reader.

Coupling LAMP to AND gate dual-CHA detector

A 10 μL aliquot of the 25 μL LAMP reaction was mixed with 1 μL of 500 nM B-Acceptor1 and F-Acceptor2, followed by heating to 95°C for 5 min and slowly cooling to room temperature at a rate of 0.1°C/s. Some 5 μL of this mixture was further mixed with 5 μL of 200 nM H1+H3, 5 μL of 1.6 μM H2+H4, and 5 μL of Reporter duplex (containing 200 nM F3, 400 nM M, and 400 nM Q) in TNaK Buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 140 mM NaCl; 1 μM (dT)21). H1+H3 and H2+H4 were separately refolded (90°C for 1 min, followed by cooling to room temperature at 0.1°C/s) in TNaK Buffer immediately before use. For each reaction, 18 μL of the final 20 μL reaction mixture was added to a well of a 384-well plate that had been pre-incubated at 37°C in a TECAN Safire plate reader. Fluorescence readings were immediately taken as a function of time.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Principle of using CHA as LAMP detector

A three-step LAMP-CHA detection pathway was designed as follows (Figure 1). In Step I, a standard LAMP reaction (See supporting information) should produce four types of single-stranded loops containing the sequences F-target, F-probe, B-target, and B probe. In Step II, a hairpin acceptor (B-acceptor) with a loop complementary to, for example, B-target, is added to the reaction mixture containing LAMP amplicons. B-acceptor is essentially a transducer, and hybridization to B-target will release domain 1, which will in turn trigger a catalytic hairpin assembly between two-hairpin substrates (H1 and H2). In Step III, the active domain 1 of the B-acceptor attaches the domain 1* on H1 as toehold, and initiates a branch migration reaction that extends to domain 3*, opening H1 and releasing domain 3. Domain 3 then binds to the domain 3* (toehold) of H2, initiating another branch migration reaction and ultimately forming the H1:H2 complex. During this process, the 3-2-1 of the B-acceptor is released, leading to further catalytic assembly of H1 and H2. In order to directly monitor the CHA reaction, a fluorescent transducer (F:Q duplex) was constructed. Formation of H1:H2 leads to displacement of an oligonucleotide-Iowa Black® (Q) from the oligonucleotide-FAM (F) in the transducer. We anticipate that the background for our circuit design should be extremely low, since hybridization of either (H1, H2) or (H1, H2, unopened B-acceptor) should be extremely slow as their interacting domains are sequestered in intramolecular secondary structures.

In order to show the utility of our method, one well-established LAMP reaction involving M13mp18 single-stranded DNA (over 7000 bases)9 was adapted to an optimized CHA circuit.28 The function of the CHA circuit was initially assayed with a surrogate for the LAMP product, ssDNA, C1 (containing the sequence 3-2-1). Reactions were carried out in physiological buffer conditions (20 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, pH 7.5). As was previously observed, C1 could catalyze the formation of H1:H2 with an apparent turnover rate of ~1 min−1. As shown in Figure 2, in the presence of 12.5 nM C1, a sharp increase in fluorescence was observed and the reaction went to completion in less than 20 min. No background was observed in the absence of C1 over 3 hours.

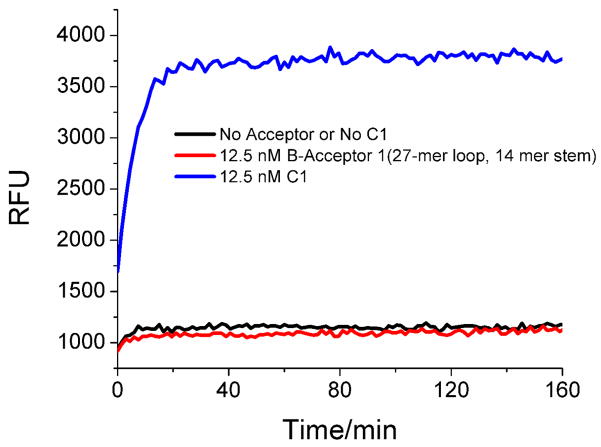

Figure 2.

Test of CHA catalyzed by C1 (3-2-1) or B–acceptor1. [C1]=[B-acceptor1]=12.5 nM, [H1]=50 nM, [H2]=400 nM, [F]=1/2[Q]=50 nM.

Further optimization of the B-acceptor (the acceptor that showed the lowest background) was carried out to ensure that background leakage in the absence of M13mp18 would be low. Systematic variation of the length of the stem and loop sequences in the hairpin revealed that a hairpin with a 27-mer loop and a 14-mer stem (B-acceptor1) yielded the lowest background signal (Figure 2, Figure S1).

Detection of LAMP amplicons from M13mp18

As a prelude to mixing LAMP and CHA reactions, we verified that the formation of the appropriate LAMP product from the M13mp18 template and the 4 primers, B3, B1c-B2, F3, F1c-F2, 15 via agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 3A). The LAMP reaction mixtures were carried out in a volume of 25 JL and incubated at 65°C for 1 to 1.5 hours, followed by heating to 80°C for 10 min to terminate the reaction.

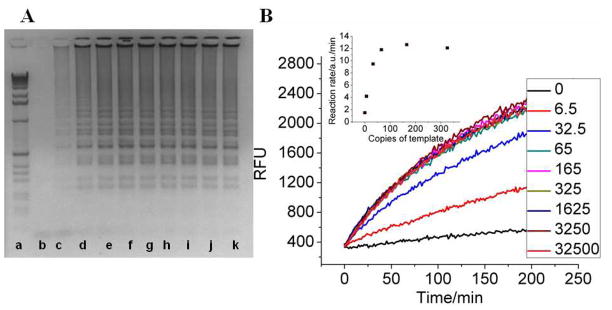

Figure 3.

LAMP reactions. (A) 2% agarose gel electrophoretic analysis of a typical 75 min LAMP reaction. Lane a: 1 kb DNA ladder (Invitrogen). Lanes b to k: LAMP products stemming from a M13mp18 target introduced at 0, 6.5, 32.5, 65, 165, 325, 650, 1625, 3250, and 32500 copies, respectively, per 25 μL reaction mixture. (B) Time-course of CHA detection via fluorescence. Inset: Reaction rate (change in fluorescence/min) as a function of copy number of the M13mp18 template.

The LAMP reaction was then mixed with the CHA detection reaction. Some 1 JL of the B-acceptor1 (500 nM) was added to 10 μL of the LAMP reaction mixture, and the samples were thermally equilibrated by heating to 95°C for 5 min, then cooling at a rate of 0.1°C/s to 37°C). An aliquot of 5 μL was added to 15 μL mixtures of pre-annealed H1, H2, and F:Q duplex. The final concentrations of B-acceptor1, H1, H2, and F:Q duplex were 12.5 nM, 50 nM, 400 nM, and 50 nM:100nM, respectively, and the development of fluorescence was followed at 37°C on a TECAN Safire plate reader (Figure 3B). While overall this procedure utilized a series of solution transfers so that each reaction could be separately optimized, it is also possible that some steps can be combined, such as the heat denaturation of the LAMP reaction and the annealing of the B-acceptor1.

As has previously been observed with LAMP, the limits of detection are extremely good (Figure 3B). As few as 7 templates (~4 ×10−19 M in 25 μL LAMP reaction mixtures; or ~1×10−19 M in final CHA detection mixtures) could be obviously discriminated from reactions lacking a template. However, it was also clear that the background leakage of the CHA reaction was slightly increased compared with that shown in Figure 2 (in TNaK buffer). This was because some components of the more complex LAMP reaction mix (e.g., betaine), might have altered the conformational equilibration of the hairpins and led to analyte-independent initiation of the cascade. Nonetheless, this background leakage was very reproducible (Figures 3–5), so it should not have impacted either qualitative or quantitative analysis. In addition, the initial rates of reaction (as opposed to the reaction end points) could be reliably utilized as either a primary or confirmatory quantitative signal. As shown in Figure 3B, inset, the initial CHA reaction rate was dependent on initial template copy numbers, especially in the low copy range from several copies to tens of copies. Notably, the dynamic range could potentially be adjusted by simply changing LAMP reaction conditions such as reaction times and enzyme concentrations.

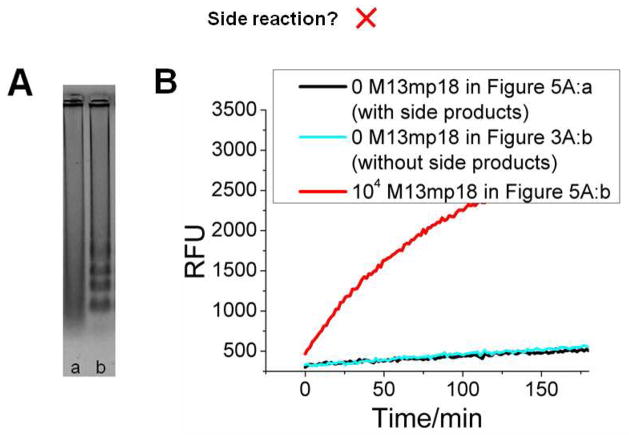

Figure 5.

Detection of true versus spurious LAMP amplicons. (A) 2% agrose gel electrophoretic analysis of a LAMP reaction without betaine after 90 min. The reactions in lanes a and b were seeded with 0 and 104 copies of M13Mp18, respectively. (B) Time-course of CHA product formation for lanes a and b in Figure 5A, and lane b in Figure 3A.

Control experiments to demonstrate CHA amplification and specificity

In this section, three control experiments were carried out to prove the utility of the CHA.

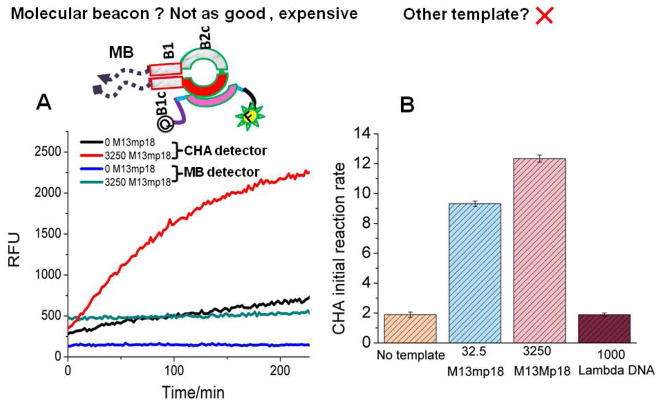

We firstly demonstrated the higher sensitivity of the CHA transducer by direct comparison with an alternative signal transducer, molecular beacons (MB, Figure 4A). A 7 base-pair stem molecular beacon was designed to be activated by the B-target, and was labeled with FAM and Iowa Black® on its 5′ and 3′ end, respectively. Here 7 base-pair stem was chosen since an optimized molecular beacon usually adapts 5 to 7 base-pair stem to make sure it is stable enough as hairpin, yet also weak enough to be easily and effectively opened by its antisense DNA.30 While the molecular beacon showed a positive signal in the presence of LAMP amplicons, the CHA transducer displayed almost 5-fold higher signal amplitude. The ability to monitor the increase in CHA-mediated signal as a function of time, as opposed to merely doing end-point analysis, should ultimately make the interpretation of LAMP reactions more reliable, and will yield higher confidence in amplicon detection.

Figure 4.

Control experiments. (A) Comparison of CHA detection of LAMP reaction products with direct molecular beacon detection. (B) Detection of the M13Mp18 template relative to a lambda DNA template.

Second, in order to ensure that the transducer was acting specifically, full-length lambda DNA (over 40,000 bases) was used as template with the 4 primers designed to amplify M13mp18. As shown in Figure 4B, the incorrect template did not yield a CHA signal.

Third, while LAMP is an extremely powerful amplification method, the fact that it occurs continuously makes it especially vulnerable to side reactions, the accumulation of parasitic amplicons, and thus the production of false positive signals. For example, in the absence of betaine, a reagent that destabilizes spurious base pairing15,31, false amplification products in the absence of template frequently arise (Figure 5A, lane a). Even with betaine, false amplification products can still sometimes occur (Figure S2).24 One of the great advantages of our CHA transducer is that since it is highly dependent on specific loop sequences, it is largely refractive to such amplicons and to false signalling (Figure 5B).

Coupling LAMP to a parallel CHA detector

To further ensure specificity of detection, it is possible to imagine probing multiple loop sequences within a LAMP product in parallel. The modularity of CHA circuit design makes this notion relatively easy to implement; for example, the loop sequences of the B-acceptor1 hairpin could be readily changed to hybridize to the F-target, B-probe, or F-probe, instead (Figure 1). As an example, we altered the loop sequence of the original B-acceptor1 to be a 25-mer antisense complement to the F-target (F-acceptor1). As observed (Figure S3), LAMP products can be detected by CHA reactions triggered by either the F-acceptor1 or B-acceptor1. It should be noted that the CHA reaction rate via transduction with the F-acceptor1 is slower than that with the B-acceptor1, which is consistent with the fact that the concentration of loops containing the B-target (or F-probe) is higher than the concentration of loops containing the F-target (or B-probe; explanation in Supporting information). There was virtually no cross activation between these two cascades (data not shown).

This experiment also demonstrated another advantage of the CHA transducer. One CHA circuit can probe different loops (i.e., different LAMP amplicons) by simply changing the loop sequence of the acceptor (which hybridizes with the loop sequence of the amplicon). All downstream reactions in the cascade can remain the same, including labeled (and often expensive) reporter molecules.

Conversely, different CHA reactions can be used to probe different loop sequences, and to multiplex reactions. To this end, we designed another CHA circuit (CHA2) to target the other LAMP loop (F-probe in Figure 1, Step I). The F-acceptor2 had a 10 base-pair stem with a loop sequence complementary to the F-probe). In order to avoid cross-talk with CHA1, the CHA2 circuit contained completely different sequences (Table S1: H3, H4, and F2-Q2). As shown in Figure S4, F-acceptor2 and CHA2 successfully monitored the appearance of the F-probe sequence. The fact that a single set of molecules could be designed and implemented with little additional optimization showcases the flexibility and robustness of CHA as a general signal transducer.

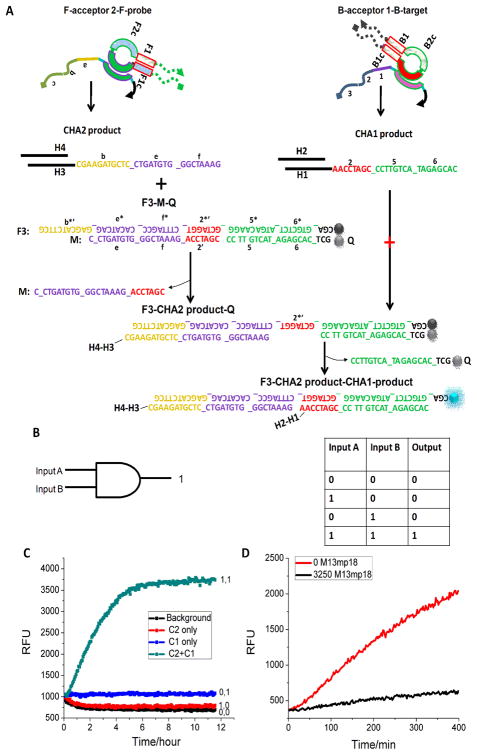

Coupling LAMP to AND gate dual-CHA detector

We further designed an AND gate that only yields a positive response when two of the correct loops exist in the LAMP products. The potential Advantage of the AND gate is that it provides a means to discriminate true LAMP amplicons from non-specific amplicons, such as primer artifacts, that may inadvertently contain a sequence that would trigger the LAMP reaction. Similar to the previous experiments (Figure 3 and Figure S4), the B-target and F-probe could be transduced to trigger the CHA1 and CHA2 circuits, respectively (Figure 6A), and the two CHA circuits would produce H1-H2 (with a 2-5-6 tail) and H3-H4 (with a b-e-f tail), respectively. Here, we used a three-strand reporter (F3-M-Q) to replace the previous F-Q (or F2-Q2) reporter duplex in both CHAs. To release F3 (with FAM) from Q (with quencher), H3-H4 (b-e-f) (CHA2 product) was firstly required to displace the M sequence and release domain 2*′ on F3. The CHA1 product H1-H2 (2-5-6) could then bind 2*′ as a toehold to displace Q. The whole pathway indicates that both CHA1 and CHA2 are necessary to yield increased fluorescence. Therefore, it represents a relatively worthy implementation of a Boolean AND gate for a diagnostics application,32–34 with B-target and F-probe as two inputs (Figure 6B true value table). Because it was difficult to obtain random or incorrect LAMP products with only one of the current loops, we used the two CHA catalysts (C1 and C2) as the B-target mimic and F-probe mimic, respectively. As shown in Figure 6C, the dual-CHA circuit produced a perfect AND gate response with C1 and C2 as inputs. Only when C1 and C2 existed could we observe the significant fluorescence enhancement. As expected (Figure 6D), compared with background (without M13mp18), the correct LAMP reaction (from 3250 molecule/μL M13mp18) produced a high CHA response in the presence of the dual-CHA detector. This proof-of-concept experiment demonstrated the strong potential of CHA to achieve higher-sepecifity detection.

Figure 6.

Proof-of-concept experiments of coupling LAMP to AND gate dual-CHA circuit proof-of-concept experiments. (A) Scheme for the AND gate pathway. (B) True value table of AND gate. (C) Time-course of AND gate using C1 and C2 as two inputs. (D) Time-course of dual-CHA response with (red) and without (black) LAMP template. [C1]=[C2] =8 nM, [B-acceptor1]=[F-acceptor2]=12.5 nM, [H1]=[H3]=50 nM, [H2]=[H4]=400 nM, [F3]=1/2[Q]=1/2[M]=50 nM.

CONCLUSION

By pairing a novel enzymatic amplification technique, LAMP, with a novel DNA computation, catalytic hairpin assembly, we preserve the best features of both: LAMP provides high sensitivity and specificity for molecular detection, while LAMP modularity and ease of readout, and suppression of parasite detection. We anticipate that this combination will ultimately make LAMP much more useful for the diagnostics community. This initial proof-of-principle can be followed by systematically varying parameters that impact both sensitivity and transduction, such as enzyme concentrations, primer concentrations, and reaction time further, and by optimizing how the two reactions are staged (potentially yielding real-time detection). By understanding how these variables impact detection and reaction kinetics, we can potentially develop tradeoffs that allow the most appropriate linear range of analyte to be determined while concomitantly speeding up the somewhat tedious reaction times, which are currently on the order of hours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Sanchita Bhadra for her suggestion on operating LAMP reaction. This article was funded by National Institute of Health (NIH Plaxco 1R01EB0007689), the National Security Science and Engineering Faculty Fellowship (NSSEFF FA9550-10-1-0169) as well as the National Institute of Health (NIH-TR01 5R01AI092839-02). The published material represents the position of the author(s) and not necessarily that of the sponsors.

References

- 1.Du Y, Guo S, Dong S, Wang E. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8584–8592. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng XX, Liu Q, Jing C, Li Y, Li D, Luo WJ, Wen YQ, He Y, Huang Q, Long YT, Fan CH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11994–11198. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Lu Y. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:7587–7590. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirks RM, Pierce NA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15275–15278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407024101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei B, Cheng I, Luo KQ, Mi YL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:331–333. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill P, Ghaemi A. Nucleos Nucleot Nucl. 2008;27:224–243. doi: 10.1080/15257770701845204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asiello PJ, Baeumner AJ. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1420–1430. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00666a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guatelli JC, Whitfield KM, Kwoh DY, Barringer KJ, Richman DD, Gingeras TR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1874–1878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton J. Nature. 1991;350:91–92. doi: 10.1038/350091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wharam SD, Marsh P, Lloyd JS, Ray TD, Mock GA, Assenberg R, McPhee JE, Brown P, Weston A, Cardy DL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E54–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker GT, Fraiser MS, Schram JL, Little MC, Nadeau JG, Malinowski DP. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1691–1696. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean FB, Hosono S, Fang LH, Wu XH, Faruqi AF, Bray-Ward P, Sun ZY, Zong QL, Du YF, Du J, Driscoll M, Song WM, Kingsmore SF, Egholm M, Lasken RS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082089499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent M, Xu Y, Kong HM. Embo Reports. 2004;5:795–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurn N, Chen PC, Heath JD, Kopf-Sill A, Stephens KM, Wang SL. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1973–1981. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, Yonekawa T, Watanabe K, Amino N, Hase T. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamine K, Hase T, Notomi T. Mol Cell Probes. 2002;16:223–229. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2002.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu S, Qu G, Guo S, Ma L, Zhang N, Zhang S, Gao S, Shen Z. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;163:845–850. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-9088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parida M, Sannarangaiah S, Dash PK, Rao PVL, Morita K. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:407–421. doi: 10.1002/rmv.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto T, Sonobe T, Hayashi K. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2616–2622. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2616-2622.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Henostroza G, Raqib R, Rahim Z, Gerhardt M, Sanga E, Hoelscher M, Notomi T, Hase T, Perkins MD. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1936–1940. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02352-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandey BD, Poudel A, Yoda T, Tamaru A, Oda N, Fukushima Y, Lekhak B, Risal B, Acharya B, Sapkota B, Nakajima C, Taniguchi T, Phetsuksiri B, Suzuki Y. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:439–443. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Njiru ZK, Mikosza ASJ, Armstrong T, Enyaru JC, Ndung’u JM, Thompson ARC. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paris DH, Imwong M, Faiz AM, Hasan M, Bin Yunus E, Silamut K, Lee SJ, Day NPJ, Dondorp AM. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:877–882. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura N, Ito K, Takahashi M, Hashimoto K, Kawamoto M, Yamanaka M, Taniguchi A, Kamatani N, Gemma N. Anal Chem. 2007;79:9484–9493. doi: 10.1021/ac0715468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaroenrama W, Kiatpathomchai W, Flegel TW. Mol Cell Probes. 2009;23:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Ellington AD, Chen X. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin P, Choi HMT, Calvert CR, Pierce NA. Nature. 2008;451:318–U314. doi: 10.1038/nature06451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:263–271. doi: 10.1021/ja206690a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang XH, Li JWJ, Perlette J, Tan WH, Wang KM. Anal Chem. 2000;72:747A–753A. doi: 10.1021/ac003001i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh HY, Shoemaker CA, Klesius PH. J Microbiol Meth. 2005;63:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou M, Dong S. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1232–1243. doi: 10.1021/ar200096g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X, Wang YF, Liu Q, Zhang ZZ, Fan CH, He L. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2006;45:1759–1762. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willner I, Shlyahovsky B, Zayats M, Willner B. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1153–1165. doi: 10.1039/b718428j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.