Abstract

Infants learn from adults readily and cooperate with them spontaneously, but how do they select culturally appropriate teachers and collaborators? Building on evidence that children demonstrate social preferences for speakers of their native language, Experiment 1 presented 10-month-old infants with videotaped events in which a native and a foreign speaker introduced two different toys. When given a chance to choose between real exemplars of the objects, infants preferentially chose the toy modeled by the native speaker. In Experiment 2, 2.5-year-old children were presented with the same videotaped native and foreign speakers, and played a game in which they could offer an object to one of two individuals. Children reliably gave to the native speaker. Together, the results suggest that infants and young children are selective social learners and cooperators, and that language provides one basis for this selectivity.

Characteristic of human nature is our distinctive sociality. Young humans naturally look towards, and interact with others to learn about their surrounding environment (Csibra & Gergely, 2009). Humans are similarly intuitive communicators and collaborators (Tomasello, 2008), who share information and goals and are spontaneously helpful (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). Social learning and cooperation appear to be effortlessly achieved, without formal instruction or relevant feedback.

Young humans’ distinctive sociality raises an important question. How do children select among potential social partners? Effective social learning and cooperation require selectivity for several reasons. First, potential teachers and collaborators may differ in their beliefs or desires, and therefore may provide conflicting signals, and discordant information. Second, the number of potential social partners and collaborators likely exceeds the child’s limited time and resources in many situations. Third, much of what children learn from others is specific to a particular culture, and most collaborative activities occur between members of the same social group. Young children therefore might profitably orient their social interactions, social learning, and prosocial behaviors toward members of their own social group.

The present studies investigate one potential source of selectivity among social partners that could be available even in infancy, and could effectively orient infants toward members of their community: preferences for novel individuals who speak the infant’s native language. Language provides information about a speaker’s national, social, and ethnic group status (Labov, 2006), and adults’ subjective inferences about novel individuals are affected by their manner or accent of speech (see Giles & Billings, 2004; Gluszek & Dovidio, 2010 for reviews). Children’s preferences for, inferences about, and learning from individuals are similarly influenced by individuals’ status as native or foreign speakers (Hirschfeld & Gelman, 1997; Kinzler, Shutts, DeJesus, & Spelke, 2009; Kinzler, Corriveau, & Harris, in press). When an adult speaks an infant’s native language, he or she may be perceived as having particularly relevant, culturally specific knowledge to share. Likewise, early selective helping of native individuals may lead to advantageous reciprocation towards the infant.

From birth, infants exhibit remarkable linguistic abilities, and attention to linguistic differences. Newborn infants prefer the sound of their maternal language, and can discriminate two foreign languages, provided they are sufficiently different in crossing a rhythmic class boundary (Mehler et al., 1988; Nazzi, Bertoncini, & Mehler, 1998). By five months of age, infants express more nuanced discriminations, for instance between the language of their home environment and another language or dialect from the same language family (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2001; Nazzi, Juscyk, & Johnson, 2000). Recent research provides evidence that language-based preferences extend beyond preferences for native speech, and include preferences for native speakers. Five-month-old infants choose to look at individuals who previously spoke in a native accent of their native language (Kinzler, Dupoux, & Spelke, 2010), and 12-month-old infants select foods that were first tasted by speakers of their native language rather than foreign-language speakers (Shutts, Kinzler, McKee & Spelke, 2009). Nonetheless, past research has not investigated the impact of infants’ preferences for native speakers in facilitating their choices among, or learning about, physical objects; nor do we know how and whether infants’ early preferences for native speech lay the groundwork for selectively collaborating with native individuals.

In an experiment that provides the motivation for the current research (Kinzler, Dupoux, & Spelke, 2007), ten-month-old infants in the U.S. and France were shown the same movies of a native English speaker and a native French speaker. After the two people had spoken in alternation, they appeared side-by-side, and each held up an identical toy and, silently and in synchrony, offered it to the infant. An illusion was created such that two real identical toys appeared simultaneously in front of the infant, seeming to have emerged from the screen. Infants in the U.S. reached for toys offered by the English speaker, whereas infants in France reached for toys offered by the French speaker, even though the toys were identical and no toy ever appeared on screen while the languages were heard (Kinzler et al., 2007). Thus, prior to speaking themselves, infants chose to engage in an interaction with a native speaker of their native language.

Two questions arise from this initial finding with infants. The first concerns how and whether infants’ preferences for native speakers influences their choices among physical objects. It is not clear from past research whether infants uniquely prefer interactions with native speakers, or whether infants’ object choices (independent of a social exchange) are also influenced by the language of their social partner. Although infants in the study described above selectively reached for a toy offered by a native speaker, their actions likely do not reflect any preferences for one toy over the other, in particular because the two toys were identical. Infants may prefer to take something that is physically offered by a native speaker, or feel wary about accepting a toy from a foreign speaker, without a preference between the two objects that these speakers offered. Alternatively, past research suggests that infants are highly attentive of social and affective information provided by others in guiding their decisions about which objects are and are not good to touch (Moses, Baldwin, Rosicky, & Tidball, 2001; Mumme & Fernald, 2003; Hornik, Risenhoover, & Gunnar, 1987; Repacholi & Meltzoff, 2007). On this story, preferences for native speakers may “spread” to the objects they endorse, leading infants to prefer a different exemplar of an object that has similar visual properties to those of the object associated with the native individual.

A second open question concerns the development of selective prosocial actions throughout early childhood, and the relationship of infants’ early language-based social preferences to those of older children and adults. Young infants who accept toys from native over foreign speakers may be particularly attentive of language, given that they are in the process of learning language themselves. It is therefore possible that these early social preferences in infancy may be distinct from later social attitudes, which could be predicated on much more sophisticated reasoning about group membership as it pertains to native vs. foreign status. In contrast, early social preferences for native speakers may set the stage for later prosocial tendencies towards native individuals; this second hypothesis posits that preferences towards native individuals would be uninterrupted across developmental time, and influence young children’s prosocial actions and choices among collaborators.

Across two experiments we tested the influence of infants’ and toddlers’ attention to native speakers in guiding infants’ object choices and giving actions. In Experiment 1, we replicated and extended past findings of infants’ selective toy-taking from native speakers by testing whether 10-month-old infants prefer to manipulate an object with the same visual features as one that was manipulated (but not offered) by a native, rather than a foreign, speaker. Experiment 2 tested whether 2.5-year-old children selectively interact with and choose to give a “present” to a native, rather than a foreign, speaker.

Experiment 1

We presented 10-month-old infants in monolingual English-speaking environments with similar movies to those described above (Kinzler et al., 2007), in which each of two people—a native speaker of English and a native speaker of French—addressed the infant in infant-directed speech in English or French. After listening to each person speak, the two people appeared side-by-side and silently held a toy. The method subsequently differed from the method of Kinzler et al. (2007) in two important ways. First, the speakers each manipulated one of two different objects on screen. Infants viewed the videos while seated behind a table on which two real objects (each resembling one of the objects on screen) were placed out of the infant’s reach. Second, in contrast to past work, the speakers never offered the objects to the infant, and never looked at or referred to the real objects on the table. The actors simply looked at the object they were holding and then faced forward, continuing to hold the object. After this presentation, infants were moved within reach of the real objects (that shared the same visual properties as those on screen) simultaneously present in the testing room, and we tested whether infants chose to manipulate the “native object”. The present study tested infants only in the U.S. The use of American infants is conservative, because research comparing responses to these films by French and American children showed that although children in both countries preferred the native individual, children also showed a small baseline preference for the French speaker (Kinzler et al., 2007).

Method

Participants

16 full-term 10-month-old infants living in monolingual English-speaking families in the greater Boston area participated in the study (7 females; mean age 10;0; range 9;16 to 10;13). Data from two additional subjects were excluded due to fussiness, and failure to make a choice on any trial.

Materials

The stimuli from Kinzler et al. (2007) were used to create the materials for this study. The speaking trials consisted of a female speaker of French or English who each spoke to the baby in child-directed speech for 10 seconds (in a 13s film). The toy modeling films showed the two (now silent) speakers simultaneously on screen; each held a different toy animal (one green frog; one black and white cow), smiled at the toy, and then smiled at the camera (15s) while holding the object. The films were projected approximately life-size on a screen that measured 92×122cm, behind a 50cm table. The infant was seated in a rolling highchair positioned along a metal track, 50cm from the table.

Design and Procedure

On each of 4 test trials, infants saw each speaker speak in turn, followed by a toy modeling trial. During toy modeling trials, both speakers appeared simultaneously for 15s and then the films froze with the speakers holding the toys and facing forward. Two other exemplars of the objects on screen were present on the table throughout the films, each placed on the side of the table as its corresponding image on screen, equidistant from the infant, yet out of reach as the infant’s high chair was 50cm from the table. At the moment the films froze, the infant’s high chair was pushed along the track to the table, where he was able to reach for one of the toys. The pairing of toys to speakers was counterbalanced across infants (for a given infant, speaker A always held toy A). The ordering and lateral position of actors was counterbalanced across infants, and the actors reversed sides on screen after the second trial. Infants’ first reach to one of the two objects within 15 seconds was coded offline by an experimenter who was blind to the pairing of object to speaker. A second observer coded 50% of participants, with reliability >95%. Data were included for any infant who reached on at least 1 of the 4 trials.

Results

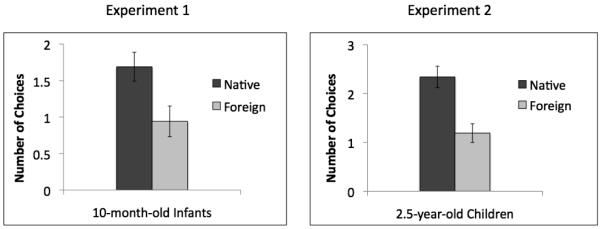

A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing number of choices for the native toy vs. the foreign toy revealed that infants reached more for the toy that was modeled by the native speaker (Mnative=1.69, SE=.198; Mforeign=.94; SE=.21, F(1, 15)=5.4, p<.05). See Figure 1, left. This effect was not due to an inherent preference for one object over the other, as the pairings of speakers and objects were counterbalanced across infants. There was no interaction with participant gender, object-to-speaker pairing, or order of speakers presented (F<1 for all analyses). A 2-tailed non-parametric sign test confirmed this result: 11 children chose more “native” toys, 1 child chose more “foreign” toys, and 4 children chose equally (p<.01).

Figure 1.

Discussion

The present results provide evidence that infants’ early attention to native speakers impacts their choices of objects. Infants’ selection between two novel toys was influenced by the speech of people observed manipulating similar toys: infants chose the “native object”. Infants demonstrated this preference even though the pairing of toys and speakers was controlled, and the two people were unknown to the child. Indeed, the two actors were equally friendly and attractive, spoke in child-directed speech, and appeared to be equally pleased with the objects they were holding.

This result is well situated within a broader literature finding that beginning early in infancy, humans are adept at learning about the physical world from their social environment (Tomasello, 2008). Infants follow an adult’s gaze toward objects (Amano, Kezuka & Yamamoto, 2004; Csibra & Gergely, 2006; Hood, Willen, & Driver, 1998) and learn many culture-specific actions and competences from the people around them (e.g., Meltzoff, 1988; Baldwin, 1993). Moreover, infants and children are selective in their socially guided learning. At 12 months, infants attend to individuals’ affective reactions to objects in deciding which objects, under which circumstances, they should use (Moses, Baldwin, Rosicky, & Tidball, 2001; Mumme & Fernald, 2003; Hornik, Risenhoover, & Gunnar, 1987; Repacholi & Meltzoff, 2007; see Vaish, Grossman, & Woodward, 2008 for a review). The research presented here suggests that culture-specific preferences among objects may be influenced, in part, by infants’ language-based social preferences.

The precise mechanism governing infants’ object choices in the current experiments, as well as in the more general literature, warrants further investigation. Most locally, infants may like objects associated with native speakers because they attend to native speakers, and therefore – even incidentally – attend to native objects. Some evidence casts doubt on a strict “attentional” hypothesis: though young infants look longer at native speakers of their native language, this pattern of results is not consistently replicated among older infants (McKee, 2008), perhaps consistent with observed shifts in familiarity and novelty preferences in looking time throughout infants’ first year of life (Colombo, 2001). Second, infants may more thoroughly process or scrutinize objects offered by native speakers, and thus might more easily encode the relevant details of objects associated with native speakers. Research that tests infants’ memory for objects, or learning about their functions, would be needed to test this possibility. Third, they might associate a valence to an object depending on the person who endorsed it. For instance, an object associated with a native individual might be seen as safe, relevant, or potentially useful for future social exchange. Finally, infants may view use of the same type of object as someone else as a social gesture. Further research could distinguish these possibilities by investigating whether the object preferences observed in Experiment 1 generalize to new, nonsocial contexts.

In Experiment 1, we provide a replication and extension of past research findings, suggesting that infants prefer objects associated with native speakers. In a second experiment, we sought to explore how early social preferences for native speakers potentially impact infants’ selective interactions and collaborations with native over foreign individuals throughout later infancy and early childhood.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested 2.5-year-old children’s interactions with and toy giving behaviors toward native and foreign speakers. We chose this age group and experimental paradigm for two reasons. First, 2.5 years provides a middle ground between tests of infants (Kinzler et al., 2007, Shutts et al., 2009), and tests of preschool and kindergarten-age children (Kinzler et al., 2009; in press). Two-and-a-half-year-old children are more linguistically sophisticated than their infant counterparts, yet are not in a schooling environment where cultural norms about native and foreign individuals might be readily transmitted. Second, we were particularly interested in testing the ramifications of social preferences for native speakers on children’s early prosocial behaviors. Past research suggests that toddler-age children engage in many helping and sharing behaviors, and display concern at the distress of others (see Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006 for a review). Toddlers participate in sharing behaviors such as giving a toy object to parents and unfamiliar adults (Hay, 1979; Hoffman, 2000; Rheingold, Hay, & West, 1976), and even younger infants and toddlers engage in instrumental acts of helping, without explicit instructions or reward (Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). Nevertheless, in past research demonstrating toddlers’ interest in collaborating with and giving to unfamiliar adults (e.g., Warneken & Tomasello, 2006), the unknown individual often dressed, talked, and behaved in a manner characteristic of the child’s cultural group. In the current research, we sought to test whether children might interact with, and give toys selectively to native rather than foreign individuals.

Two-and-a-half-year-old children in both the U.S. and France were shown the same movies of one person who spoke in English, and another person who spoke in French. In a subsequent “magical giving game,” children were shown two types of trials: 1) “giving” trials, where participants were given an object described as a “present” that they could place in a box to give to one of the two speakers. When they did so, the toy appeared on screen in front of the speaker whose box the child had chosen, and the recipient of the toy reacted with a positive expression; 2) “taking” trials, in which the individuals on screen each manipulated the same object, and then silently and in synchrony lowered the toy, and two “real” toys appeared on the table for the child to grasp. Children’s choices of giving to and taking from the native or foreign speaker were recorded.

Method

Participants

2.5-3-year-old children living in monolingual English-speaking families in the greater Boston area or monolingual French-speaking families in Paris (N=32; 16 in each location) participated in the study (16 females; mean age 33 months; range 30-36 months).

Materials

The French- and English-speaking films from Experiment 1 served as video stimuli. Films were projected approximately life-size on screen, with the child seated at the table in front of the screen. The table was positioned 50cm from the screen, to allow for an experimenter to move between the screen and the table. On the table were two cardboard boxes (20cm3) with felt openings on top and on the back, such that a child could place something in the box on top, and an experimenter could remove it from the back of the box. Boxes were placed on the left and right side of the table, equidistant from the child.

Procedure

Children were first instructed in the giving game. An experimenter sat facing the child, between the screen and the table. A series of pairs of cartoon animals appeared on the left and right sides of the screen, and children were shown that when a “present” (different colored toy balls) was placed in one of the two boxes, the present would appear on screen, accompanied by a chime, and reward the animal on the corresponding side of the screen. Children next saw 2 test blocks: each of which included a “give” and a “take” trial, in counterbalanced order. At the start of each test bock, children were shown the French-speaking and English-speaking movies, in counterbalanced order. On “give” trials, a static image of the two individuals appeared side-by-side on screen, and children were instructed to “give a present” to one of the two individuals. When the child placed the present in one of the two boxes, a chime noise was played, the present appeared on the corresponding side of the screen, and the chosen individual smiled. On “take” trials, each individual held up an identical toy, silently and in synchrony, and then lowered the tow as if offering to the child. At the moment at which the toys disappeared off screen, two real toys “magically” appeared from behind the table for the infant to grasp, giving the illusion that they emerged from the screen. The objects were attached by Velcro to PVC piping that rotated from behind the table, and landed on the table equidistant from the infant and in front of the silent and motionless images of the two individuals. Children’s first reach for a toy was recorded. Order of presentation of speakers (native vs. foreign first), order of trials (give vs. take first) and lateral position of presentation (native speaker on the left or right), was counterbalanced across children.

Results

Overall, children interacted selectively with native over foreign speakers. Out of a possible 4 trials, children chose to give to or take from the native speaker 2.34 times, and the foreign speaker 1.19 times1. A repeated-measures ANOVA with choices to native and foreign as a within-subjects factor, and location (France vs. U.S.) and condition (give first or take first) as between subjects factors revealed that children selectively chose the native interactions (F(1,28) = 7.91, p=.009), and there was no difference between American and French children’s preference for speakers of their native language F(1, 28 = .05, p=.82), and no interaction with condition (give or take first), F(1,28=.47, p=.50). The finding that there was no difference between American and French infants’ preferences for the individuals depicted here provides further support that the stimulus set presented in Experiment 1 was conservative, as it generated a slight preference for the French individual: French children interacted on average with the French speaker 2.56 times; and the English speaker 1.31 times; American children interacted with the English speaker 2.13 times and the French speaker 1.06 times.

Analyzing choices of giving and taking separately, on “give” trials, children’s choices reflected a preference for giving to the native speaker. Children on average gave 1.3 times to the native speaker, and .66 times to the foreign speaker (F (1, 30) = 6.29, p=.018), with no interaction with location (U.S. or France) (F (1,30) = .699, p=.41). On “take” trials, children chose the native speaker an average of 1.03 times, and the foreign speaker an average of .53 times. Children’s choices for taking revealed a marginally significant preference for taking from the native over the foreign speaker (F(1, 3)=2.95, p=.096), again with no interaction of location tested (F(1,30)=.18, p=.67). Though children’s relative preference for native over foreign speakers was not significantly different for “give” vs. “take” trials, children’s spontaneous comments sometimes reflected skepticism over the “magic trick” involved in the taking trials. This observation, coupled with only marginally significant results on taking trials, may suggest that the toy giving method, rather than the toy taking method described here, may be the more appropriate and useful measure for future research with children of this age.

Though giving appears to be a robust indicator of children’s preferences for native individuals, it should be noted that children value fairness and reciprocity (Olson & Spelke, 2008), and thus it is conceivable that children’s giving behaviors might be accentuated by the fact that the other person had first given something to the child. To account for this alternative possibility, we analyzed only at the first trial of the participants in the “give first” condition: these children had the opportunity to give prior to anyone first giving anything to them. Children here children selectively gave to the native speaker on the first trial, when they had no knowledge of any necessary future reciprocation (12 children gave to the native speaker and 4 children gave to the foreign speaker, binomial test p<.05). Thus, children’s preferences for giving to the native speaker cannot be accounted for by past reciprocal interactions with that individual.

Discussion

When given the opportunity to participate in a prosocial giving game with one of two individuals, children reliably gave to the speaker of their native language. Children showed this pattern of behavior even though other properties of the two individuals were controlled by testing half of participants in the U.S. and half in France, with identical displays. Moreover, selective giving behaviors were observed on even the first trial, where children had just one opportunity to give, and were thus unaware that any subsequent reciprocal interactions would occur.

The results of Experimental 2 provide evidence of a developmental continuum that persists from infancy throughout early childhood, whereby children demonstrate social preferences for native speakers during the toddler years. Moreover, children’s selective giving to native over foreign individuals raises broad theoretical questions concerning the development of prosocial behavior more generally. Are humans inherently prosocial? Are young infants predisposed to share resources with others (Warneken & Tomasello, 2009), or, might children be predisposed in particular for cooperative, prosocial gestures, towards members of their native community?

Additionally, this study provides a novel method used to test toddlers’ giving behavior, while using highly controlled videotaped events. Many past studies that test children’s early helpful actions towards others test children’s responses to live individuals. While methods that present live actors have the virtue of naturalness and ecological validity, the present method provides an opportunity to test children’s prosocial gestures under controlled experimental conditions. By virtue of being videotaped events, the social stimuli presented to each child were identical. Nonetheless, the videos were life-sized, engaging, and elicited social behaviors. This method might be expanded to explore children’s giving actions in response to other social variables.

General Discussion

Together, the results of Experiments 1 and 2 provide evidence that children’s attention to native speakers influences their choices of physical objects and of giving behaviors. In Experiment 1, 10-month-old infants preferentially reached for an object when they first saw a video image of that type of object being manipulated by a native rather than a foreign speaker. In Experiment 2, 2.5-year-old children gave a present to the native over the foreign speaker. Young children therefore may view members of their own language group as better informants about desirable objects, and as more appropriate recipients of prosocial gestures.

The finding of infants’ selective choices of ‘native’ objects raises potential questions about the nature of children’s naïve pedagogy (Csibra & Gergely, 2009). There is much evidence to suggest that infants invested in, and capable of learning about the physical world from others. Might infants be particularly compelled to see some individuals as better teachers than others? Given the vast diversity of human cultures and traditions, infants have to learn their culture’s manner of dress, speaking, ritual, and other practices. It is possible that infants learn equally from all teachers – yet, the teachers available often happen to be those with local, relevant knowledge to share. Or, infants may value the teachings of some individuals over others, with a particular investment in learning from those who are members of their native community. Because infants are likely to learn primarily about the objects that they attend to and manipulate, the preferences observed in Experiment 1 may lay the groundwork for future learning about culturally relevant objects, from culturally knowledgeable teachers. Related to this possibility, past research shows that North American 4-year-old children learn the names of objects they are told are “from downtown” rather than “from Japan” (Henderson & Sabbagh, 2007), and trust the testimony of native, rather than foreign-accented speakers for learning the silent function of objects (Kinzler et al., in press). Because the present experiment did not test infants’ learning directly, however, the present findings provide evidence only for a potential precursor to selective learning from some individuals over others.

In Experiment 2, young children selectively interacted with native speakers, and gave preferentially towards native speakers, even when those native speakers had not yet offered a gift in exchange to the child participant. These findings suggest that an important precursor of collaboration and reciprocity—a willingness to give to or share with others—is selectively exhibited toward members of children’s own language group. Moreover, this research provides evidence of a consistent developmental trajectory, whereby early infant preferences for native speakers are observed from infancy throughout toddlerhood. Like Experiment 1, Experiment 2 raises questions about the causes and consequences of children’s selective giving. Young children may give to native speakers selflessly, or because they expect acts of giving to be reciprocated (Olson & Spelke, 2008). Toddlers’ giving of objects in Experiments 2 may be a precursor to collaboration: by giving to others of the same language group, children may increase their chances of engaging in collaborative activities with those ingroup members. The degree to which early giving is considered a prosocial action, and the degree to which it fosters collaboration, await future investigation. The experimental paradigms presented here might be expanded to test these related questions, given that these paradigms offer novel, highly controlled methodologies to test children’s social actions.

More generally, the results of Experiment 2 relate to broader theoretical questions about children’s role as prosocial actors. Research suggests that part of what defines our humanity may be our capacity for altruism, and that sharing resources with others provides one context in which altruism can occur (Warneken & Tomasello, 2009). The results presented here raise the question of whether altruistic acts – represented as giving here, but possibly also extending to other behaviors such as helping or empathizing – might emerge differentially depending on the social properties of the individual recipient. Are early prosocial actions directly differently toward ingroup and outgroup individuals, and does the emergence of prosocial behaviors follow a differential time course depending on the identity of the person in need? The methods presented here might be integrated with research probing the development and nature of early prosocial behavior across a variety of contexts.

Finally, future research might investigate the interplay of children’s preferences for native speakers with reasoning about other social information. For example, how do infants weigh social category information against information about an individual’s competence? Additionally, how would social preferences and learning based on language compare to preferences based on other social categories, such as gender or race? Research with 5-year-old children provides evidence that though children exhibit social preferences based on both language and race when presented in isolation, when accent is pitted against race children choose to be friends with a native speaker who is of a different race, rather than a foreign speaker who is of the child’s race (Kinzler et al., 2009). It is not known, however, whether infants will show selective object preferences and giving behaviors based on race or other social group variables, or how race, gender, and language will interact in guiding children’s early social choices. Finally, the present research tests children who are monolingual and speak their society’s dominant language. The need to investigate the role of multilingualism in guiding early social preferences based on language is clear. Future studies will continue to address the nature of early social preferences, particularly as related to cultural learning and prosocial behaviors, and the potential malleability of human social preferences as a result of exposure to diverse early environments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marine Buon for assistance testing participants. This research was supported by NIH Grant HD23103 to E.S. Spelke.

Footnotes

These two numbers do not add up to 4 due to trials in which children did not give or take from either individual, or attempted to take from both at once.

References

- Amano S, Kezuka E, Yamamoto A. Infant shifting attention from an adult’s face to an adult’s hand: A precursor of joint attention. Infant Behavior & Development. 2004;2:64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin D. Early referential understanding: Infants’ ability to recognize referential acts for what they are. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:832–843. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch L, Sebastián-Gallés N. Native-language recognition abilities in 4-month-old infants from monolingual and bilingual environments. Cognition. 1997;65:33–69. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(97)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo J. The development of visual attention in infancy. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:337–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csibra G, Gergely G. Social learning and social cognition: The case for pedagogy. In: Munakata Y, Johnson MH, editors. Processes of Change in Brain and Cognitive Development. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad T. Prosocial development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 6th ed Vol. 3. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Billings A. Language attitudes. In: Davies A, Elder E, editors. The Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Blackwell; Oxford: 2004. pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gluszek A, Dovidio JF. The way they speak: A social psychological perspective on the stigma of nonnative accents in communication. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:214–237. doi: 10.1177/1088868309359288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF. Cooperative interactions and sharing between very young children and their parents. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:647–653. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld LA, Gelman SA. What young children think about the relationship between language variation and social difference. Cognitive Development. 1997;12(2):213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson AME, Sabbagh MA. Preschoolers do not learn the names of foreign objects. Poster presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Boston, MA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hood BM, Willen JD, Driver J. Adult’s eyes trigger shifts of visual attention in human infants. Psychological Science. 1998;9:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R, Risenhoover N, Gunnar M. The effects of maternal positive, neutral, and negative affective communications on infant responses to new toys. Child Development. 1987;58:937–944. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Corriveau KH, Harris PL. Children’s selective trust in native-accented speakers. Developmental Science. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00965.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Dupoux E, Spelke ES. The native language of social cognition. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:12577–12580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705345104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Shutts K, DeJesus J, Spelke ES. Accent trumps race in guiding children’s social preferences. Social Cognition. 2009;4:623–634. doi: 10.1521/soco.2009.27.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labov W. The Social Stratification of English in New York City. Second Edition Cambridge University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McKee CB. Harvard University; 2006. The effect of social information on infants’ food preferences. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Mehler J, Jusczyk P, Lambertz G, Halsted N, Bertoncini J, Amiel-Tison C. A precursor of language acquisition in young infants. Cognition. 1988;29:143–178. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(88)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff AN. Infant imitation after a 1-week delay: Long-term memory for novel acts and multiple stimuli. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:470–476. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses L, Baldwin D, Rosicky J, Tidball G. Evidence for referential understanding in the emotions domain at twelve and eighteen months. Child Development. 2001;72:718–735. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumme D, Fernald A. The infant as onlooker: Learning from emotional reactions observed in a television scenario. Child Development. 2003;74(1):221–237. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Bertoncini J, Mehler J. Language discrimination by newborns: Toward an understanding of the role of rhythm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1998;24:756–766. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.24.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Jusczyk PW, Johnson EK. Language discrimination by English-learning 5-month-olds: Effects of rhythm and familiarity. Journal of Memory and Language. 2000;43:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Spelke ES. Foundations of cooperation in young children. Cognition. 2008;108:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repacholi BM, Meltzoff AN. Emotional eavesdropping: Infants selectively respond to indirect emotional signals. Child Development. 2007;78:503–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold HL, Hay DF, West MJ. Sharing in the second year of life. Child Development. 1976;47:1148–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K, Kinzler KD, McKee CB, Spelke ES. Social information guides infants’ selection of foods. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2009;10:1–17. doi: 10.1080/15248370902966636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. The origins of human communication. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Grossmann T, Woodward A. Not all emotions are created equal: the negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:383–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science. 2006;311:1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy. 2007;11:271–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Varieties of altruism in children and chimpanzees. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13:397–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]