Abstract

This study explores the longitudinal association between academic achievement and social acceptance across ethnic groups in a nationally representative sample of adolescents (N = 13,570; Mage = 15.5 years). The effects of school context are also considered. Results show that African American and Native American adolescents experience greater social costs with academic success than Whites. Pertaining to school context, findings suggest that the differential social consequences of achievement experienced by African Americans are greatest in more highly achieving schools, but only when these schools have a smaller percentage of Black students. Students from Mexican decent also showed differential social costs with achievement in particular contexts. The implications of these findings to theory, policy, and future research are discussed.

The Social Costs of Academic Success across Ethnic Groups

Despite significant progress being made toward closing ethnic gaps in achievement, their relative stability over the past two decades has raised their priority within the broader political agenda and caused them to become recognized as one of the most important civil rights issues of the 21st century (Paige, 2004). Across virtually all measures, Black, Hispanic, and Native American students in the United States earn lower grades, drop out more often, and attain less education than Whites or Asian Americans (Perie & Moran, 2005). While structural and social burdens, often experienced disproportionately by minorities, such as socio-economic status (McLoyd, 1990), single parent families (Pong, 1998), and school or neighborhood disadvantage (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993) are important factors to consider, the dynamics of social acceptance among academically stigmatized groups are also of theoretical and practical interest (Ogbu, 2004; Spencer, Cross, Harpalani, & Goss, 2003; Steele, 1998).

Social acceptance, particularly critical during adolescence when the opinions and judgments of peers become increasingly important, is considered a basic need, closely tied to motivation and behaviors (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Research exploring the association between achievement and social acceptance suggests a positive cyclical relationship; achievement leading to greater social acceptance and social acceptance leading to greater levels of achievement (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1997; Wentzel, 1991, 2005). These findings, combined with evidence that social acceptance is an essential component of adolescent self-worth (Harter, 1999), suggest that any breakdown in this relationship could have particularly adverse consequences to development. The extent to which particular ethnic groups experience differential social costs with achievement is therefore an important area of research and theory.

Theories Predicting Differences across Ethnic Groups in the Social Costs of Achievement

In order to understand the current experiences and perspectives of a particular minority group, it is important to consider the history of the group’s relationship to the dominant culture (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Ogbu, 1999; Ogbu, 2004). Specifically, in their oft-cited paper, Fordham and Ogbu (1986) argue that involuntary minority groups, such as African Americans and Native Americans, whose presence in the U.S. stems back to colonization and enslavement, have developed a collective identity in opposition to the mainstream White culture. Furthermore, Ogbu and colleagues suggest that, for these groups, academic success may be stigmatized by peers as “acting White”, and thus attainment of higher grades in school may have differential social consequences (Ogbu & Simons, 1998).

Several scholars, however, have challenged the conceptual underpinnings of this perspective. Cross (2003), for example, has argued that resistance to education is in no way fundamental to African American culture, and that the roots of achievement problems lie not in the legacy of slavery, but within specific structural inequalities that have and still continue to directly affect minority groups. Furthermore, Spencer and Harpalani (2008) argue that Ogbu and colleagues make broad unwarranted assumptions that de-contextualize and over-generalize the experiences of African American youth, while also ignoring the importance of meaning-making processes. In particular, Spencer and Harpalani (2008) emphasize that the “acting white” phenomenon is not a cultural syndrome that is pervasive, but rather a coping mechanism: a reaction to stereotypes and experiences of discrimination experienced in particular contexts.

Spencer and colleagues therefore articulate an alternative interpretation of the “acting White” phenomenon that focuses on processes of identity development, and experiences with stigma and discrimination (e.g., Spencer, Noll, Stoltzfus, & Harpalani, 2001; Spencer et al., 2003; Spencer & Harpalani, 2008). Important to this perspective are normative developmental processes during adolescence. Specifically, adolescence is an important time for youth to engage in identity exploration in various domains (e.g., career, ethnic identity). While members of the majority group generally take their ethnic identity for granted, ethnic minority adolescents have the additional task of having to negotiate the meaning of their membership in a group whose customs may often be devalued by mainstream society (Cross, 1991; Phinney, 1990; Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990). As part of this identity formation process, Cross (1991) has described that ethnic minorities often go through a stage referred to as immersion-emersion, in which they immerse themselves within their own ethnic culture and have a tendency to reject the perspectives of the dominant group.

During this sensitive stage of identity development, minority adolescents tend to react to negative academic stereotypes directed toward their group in a particular context by labeling behaviors associated with success within that context as “acting White” (Spencer, et al., 2003). Spencer and colleagues, therefore suggest that the “acting White” phenomenon is not the result of a broad cultural frame of reference (as Ogbu’s theory suggests), but rather the result of a particular coping response to negative stereotypes that are experienced in specific contexts. From this perspective, it is the current stigmatization of minority groups that drives some adolescents to reject expectations and values of the dominant group, rather than any inherent oppositional orientation towards schooling. Under Spencer’s framework, stigmatized minority groups other than African Americans, would therefore also be expected to experience social costs with academic success. Furthermore, contextual factors, such as school characteristics, would also be expected to play an important role.

The theory of stereotype threat is also of direct relevance to the proposition that academic achievement may be coming at a greater social cost for particular groups. Steele (1997, 1998) has discussed how the burden of academic stereotypes, and the prolonged exposure to such stereotypes at the group level, may create social costs with achievement for members of stigmatized groups. According to this perspective, when an individual becomes aware of a negative stereotype directed towards their group, they experience anxiety related to the possibility of conforming to the stereotype, which in turn affects their performance. Thus, as a self-protective mechanism, prolonged exposure to negative stereotypes in a particular domain is thought to be associated with psychological disengagement from that domain (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005; Osborne, 1997; Steele, 1997). Steele’s work, therefore, suggests that the collective devaluing of academics among stereotyped groups may lead individuals who are part of those groups to experience greater social costs with achievement (Steele, 1997).

Related Empirical Findings

Support for the “acting White” proposition has been derived from several ethnographic studies of African American students, conducted across multiple contexts (e.g., Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Ogbu, 1999). These studies generally found that attitudes and behaviors conducive to academic attainment, such as studying, reading, and participating in class, are often stigmatized as “selling out” or “acting White” (e.g., Fordham & Ogbu, 1986). Other more recent qualitative studies, however, have failed to find that Black adolescents experience any oppositional orientation towards achievement (e.g., Akom, 2003; Tyson, 2002).

Additionally, the few quantitative studies that have examined the social costs of academic success have thus far failed to establish that achievement leads to greater social costs for particular groups. Specifically, using data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS), two studies have attempted to test the proposition that African Americans experience greater social costs with academic success (Ainsworth-Darnell & Downey, 1998; Cook & Ludwig, 1997). The NELS survey included self-report measures of academic achievement, popularity, and harassment. Using these measures, both studies found no evidence to suggest that African American students experienced greater social costs with achievement.

While this research calls into question the social costs proposition, finding from these studies are limited in several ways. Firstly, both studies are based on the same dataset and therefore do not offer an independent replication of findings. Secondly, neither study uses a longitudinal design to test the association between achievement and social acceptance: both studies only considered associations between self-report items within a single time-point. Furthermore, these studies only look at a narrow age range and do not compare social costs across all of the major U.S. pan-ethnic groups. Finally, neither study uses multilevel modeling techniques, which allow for a more adequate consideration of individual and school-level variables (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

The Importance of School Context

Individuals develop within particular environmental contexts, and these contexts play a pivotal role in development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Spencer, 1999). The environment of a school, specifically its achievement level and the proportion of same-race students in the school, may play an important role in moderating the relationship between achievement and social acceptance. Research examining inter-group relations, for example, has demonstrated that in competitive or high achieving contexts, where both groups are being evaluated on the same criterion, racial tensions and discrimination are likely to increase (see Brewer & Kramer, 1985 for a review). Furthermore, recent qualitative data suggest that competitive schools may breed an environment of animosity, particularly when there is a disproportionate under-representation of disadvantaged students (Tyson, Darity, & Castellino, 2005).

The proportion of same-race students in a school is therefore also an important factor that may influence the social costs of academic success for minority adolescents. Specifically, with more same-race students present, it is possible that experiences of stigmatization and discrimination may occur less often or be less pronounced. Along these lines, researchers have argued that, in largely Black schools, students are less likely to associate racial characteristics with achievement and therefore less likely to stigmatize achievement related behaviors (O’Connor, Fernandez, & Girard, 2007). Furthermore, students in largely Black schools have been found to hold more pro-school attitudes (Goldsmith, 2004), and higher levels of school attachment (Johnson, Crosnoe, & Elder, 2001). This work suggests that the social costs of academic success may be ameliorated for minority students in schools with a higher proportion of same-race students.

Purposes of the Current Study

The purpose of this paper is to explore the association between achievement and social acceptance across ethnic groups in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Specifically, we will consider the social costs of achievement for all of the major pan-ethnic groups in the United States (Non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans), as well as sub-groups within the Hispanic and Asian pan-ethnic categories. We will then determine whether socioeconomic and contextual factors (family SES, school SES, family structure, school-level achievement, school safety, school type, and school size) are able to account for any differences in social costs across groups. Based on the theories discussed (Ogbu & Simons, 1998; Spencer & Harpalani, 2008; Steele, 1998), we hypothesize that, even after accounting for background factors, stigmatized ethnic groups, such as African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans, will, on average, experience greater social costs with achievement than Whites.

Having established differences across groups, we will then explore factors that may account for variation in social costs within groups. Specifically, gender and immigrant status will be considered as potential moderators of social costs. With respect to gender, previous work suggests that the dynamics of stigma and achievement are somewhat more problematic for African American males than females (e.g., Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998; Osborn, 1997). Thus, gender will be explored as a potential moderator.

Additionally, a number of scholars have argued that immigrant status is an important factor explaining differences in attitudes towards academic attainment (e.g., A. Portes & Zhou, 1993; Spencer et al., 2003). Furthermore, research has indicated that immigrant status influences the extent to which discrimination is perceived (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000). Based on this work, we will test the hypothesis that more recent Hispanic, Asian, or Black immigrants experience less social costs with academic success than their more recent immigrant counterparts.

Our final analyses will focus on exploring whether social costs are dependent on school context. Specifically, based on the research discussed above, we will considered whether the racial composition and achievement level of a school moderate the relation between academic achievement and social acceptance. In relation to school context, we hypothesize that minority groups will show higher social costs with academic success in higher achieving schools. We also hypothesize that the presence of same-race students will serve as a protective factor in these contexts, buffering the level of social costs experienced with academic achievement.

Method

Data

The current study utilizes data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health is an ongoing nationally representative study of 7th through 12th graders selected from 80 high schools and 52 feeder (middle and junior high) schools in 1994. All available students in each of the participating schools initially completed the In-School Questionnaire (n = 90,118). A sub-sample of students then completed the Wave I In-Home Interview (n = 20,745) in 1995, followed by the Wave II In-Home Interview in 1996 (n = 14,738). In-Home Interviews can also be linked to school-level data reported by school administrators, as well as to data from parent interviews.

Sample

The sample for the current study consisted of adolescents who participated in both the Wave I and Wave II In-Home Interviews, and were assigned a valid sample weight as part of the Add Health nationally representative sample (n = 13,570) (see Chantala & Tabor, 1999 for details on the Add Health sampling procedures). Sample descriptive statistics by pan-ethnic group are presented in Table 1, and are described in the results section.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Ethnic Group

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Native | Mixed | Other | F(6, 123) | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 15.46 | 15.71 | 15.63 | 15.77 | 15.38 | 15.38 | 15.22 | 1.36 | .005 |

| 2. Male (%) | 50.0 | 49.2 | 51.1 | 53.8 | 64.0 | 49.4 | 52.2 | 1.31 | .001 |

| 3. SES | 2.89a | 2.54b | 2.11c | 3.06a | 2.42b | 2.72b | 2.70b | 17.79*** | .063 |

| 4. Single Parent Family (%) |

26.1b | 58.1a | 33.2b | 16.5c | 46.6a | 38.3b | 35.8b | 50.28*** | .061 |

| 5. Foreign Born Parent (%) |

3.6d | 3.3d | 55.9b | 82.2a | 1.2d | 14.7c | 46.6b | 60.55*** | .399 |

| 6. GPA (Wave I) | 2.87b | 2.58d | 2.61d | 3.19a | 2.49d | 2.70c | 2.80b,c | 22.74*** | .036 |

| 7. Social Accept. (Wave I) |

.051a | −.068b | −.030a | −.116b | −.184a,b | −.071a,b | −.051a,b | 2.81** | .003 |

| 8. Social Accept. (Wave II) |

.070a | −.033b | −.119b | −.126b | −.039a,b | −.158b | −.224a,b | 7.20*** | .007 |

| n | 7,051 | 2,663 | 2,132 | 843 | 78 | 688 | 104 | ||

Note. Table values are population point estimates or proportions which account for the Add Health sampling strategy. Different subscripts across rows represent ethnic group contrasts that are significant at the 95% confidence level.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Models containing only individual-level variables (models 1–3, 5, 6) excluded 5% of cases due to missing values on one or more covariates. Additional models (model 4, and models 7 thru 15), also excluded schools with missing school-level data and therefore had slightly higher levels of overall missingness (approximately 7% of cases). Those who were excluded from analyses due to missing data were not found to be different from those included in the analysis on any of the background or substantive variables considered in the study (all point-biserial and phi correlations were below a magnitude of .10). The exclusion of cases with missing data was therefore assumed to add little substantive bias to the reported results.

Measures

Race/ethnicity

Racial/ethnic categories were created based on self-report items from the Wave I In-Home Interview. Participants first reported whether or not they are of Hispanic origin. Next, participants indicated the racial/ethnic category or categories they belong to (Asian, Black or African American, Native American, White, or Other). Those who reported being part of two or more categories were classified as mixed racial, and the remaining individuals were classified into the standard categories of non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Native American, and other. Sample sizes and demographics for each race/ethnicity are included in Table 1. In addition to the pan-ethnic groups described above, individuals who identified themselves as Hispanic or Asian also identified the specific sub-group(s) that they belong to. For Hispanics, we consider Mexican (n = 1041), Puerto Rican (n = 336), Cuban (n = 294), and Central or South American (n = 195) groups separately for some analyses. For Asians we consider Chinese (n = 191) and Filipino (n = 360) groups separately. Other Asian sub-groups were not considered due to small sample sizes.

Grade point average

Grade averages at Wave I were calculated from self-reports of achievement in each of the four major subject areas (“English or language arts”, “history or social studies”, “mathematics”, and “science”). Participants were asked to report their grade at the most recent grading period on a four point scale from “A” to “D or lower”. The four items were averaged to create an overall score ranging from 1 (all D’s or lower) to 4 (all A’s) representing each participant’s GPA at Wave I (Cronbach’s α = .75). The four item scale was then standardized for use in the reported models. Self-reported GPA has been shown to be highly correlated with actual GPA and therefore can be considered an adequate proxy for actual levels of achievement (Gonzales, Cauce, Friedman & Mason, 1996).

Social acceptance

Social acceptance was measured using four items from the Wave I and Wave II In-Home Interviews. Scale items map closely onto established conceptualizations of perceived social support, loneliness, and sense of belonging (e.g., Hagerty & Patusky, 1995; Russell, 1996). The term social acceptance is therefore used broadly in this paper to encompass all three of these closely related concepts. The first item asked participants how strongly they agree or disagree that they “feel socially accepted”. Responses for this item were on a five point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The remaining three items asked participants to report how often in the past week “people were unfriendly” to them, how often they “felt that people disliked” them, and how often they “felt lonely”. Responses to these items were on a four point scale ranging from “never or rarely” to “most of the time or all of the time”. Items were standardized, and averaged such that higher scores indicated higher levels of social acceptance (lower levels of social isolation). A log transformation was performed to reduce skewness and robust standard errors were used in all reported models to account for remaining deviations from normality The average inter-item correlation for scale was .32, and the internal reliability was .65 at Wave I, and .66 at Wave II. These are equivalent to reliabilities of .79 and .81 for an 8-item scale with equivalent inter-item correlations (Cronbach, 1951). Internal reliability of the scale was also very similar across ethnic groups (.66 for Whites, .64 for African Americans, .65 for Hispanics, .63 for Asians, and .63 for Native Americans). Furthermore, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses both suggested that a single factor structure was the most appropriate solution for all five pan-ethnic groups.

Individual-level disadvantage

Socioeconomic status (SES) and family structure were considered as indicators of individual level disadvantage. SES was measured from youth reports of the highest level of education obtained by a currently residing parent. Level of education was recoded to the following four point scale: (1) less than high school (2) graduated from high school or obtained a GED, (3) some college or post-high-school technical training, and (4) graduated from college or more. Where youth reports were missing, parent self-reports were used in order to minimize missing data (parents responded to an identical question with the same response categories). Family structure was dummy coded with 1 indicating single parent family.

Other individual-level variables

Age, gender, and immigrant status were also included in multi-level models. Immigrant status and age were based on youth reports. Immigrant status was dichotomously coded with 1 indicating a foreign born mother/primary caregiver. Coding immigrant status in this manner is synonymous with comparing first and second generation adolescents (foreign born parents) to third generation or greater adolescents (U.S. born parents). Age was mean centered so that the model intercepts remained interpretable as the average aged adolescent. Gender was recorded by the Add Health interviewer during the Wave I In-Home Interview and was dichotomously coded with 1 indicating male. Population means and standard deviations for all individual-level variables are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Individual-level Variables (Level 1)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||

| 2. Male | .05 | – | ||||||

| 3. SES | −.06 | .02ns | – | |||||

| 4. Single Parent | .05 | −.02ns | −.23 | – | ||||

| 5. Foreign Born Parent | .05 | .01ns | −.12 | −.04 | – | |||

| 6. GPA (Wave I) | −.13 | −.14 | .27 | −.17 | .03 | – | ||

| 7. Social Accept.(Wave I) | −.11 | .09 | .09 | −.08 | −.02ns | .13 | – | |

| 8. Social Accept.(Wave II) | −.07 | .08 | .10 | −.08 | −.04 | .13 | .49 | – |

| M | 15.52 | .503 | 2.74 | .319 | .130 | 2.79 | .012 | .015 |

| SD | 1.61 | .500 | 1.06 | .466 | .336 | .775 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. All table values are population estimates which account for the Add Health sampling strategy. All correlations with a magnitude of .03 or larger are significant at the 95% confidence level. ns = non-significant.

School-level variables

At the school level, five measures of school disadvantage were considered: safety, SES, achievement, size, and type (public vs. private or catholic). Means and standard deviations for all school-level variables are reported in Table 3. With respect to safety, all students who completed the In-School Survey (a near census of each school) were asked how strongly they agree or disagree that they “feel safe at school”. By aggregating responses to this item, average levels of safety were calculated for each school. An identical procedure was also carried out to compute an aggregated school-level SES score based on student reports of parent education from the In School Survey. This aggregation method is akin to techniques used in previous Add health studies (e.g., Crosnoe, Cavanagh, & Elder, 2003).

Table 3.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for School-level Variables (Level 2)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Black Schoola | – | ||||||||||

| 2. % Black | .87*** | – | |||||||||

| 3. Hispanic Schoolb | .01 | .00 | – | ||||||||

| 4. % Hispanic | .05 | .08 | .75*** | – | |||||||

| 5. % Asian | −.07 | −.05 | .42*** | .31*** | – | ||||||

| 6. % Native Am. | −.09 | −.13 | .03 | .19* | −.11 | – | |||||

| 7. SchSES | −.08 | .02 | −.24** | −.24** | .17* | −.25** | – | ||||

| 8. SchSafety | −.48*** | −.40*** | −.12 | −.25** | −.11 | −.16* | .40*** | – | |||

| 9. SchAchieve | −.30* | −.30** | −.05 | −.28** | .00 | −.13 | .55*** | .57*** | – | ||

| 10. Log Size | .29* | .24** | .17* | .21* | .25** | −.12 | −.08 | −.56*** | −.27** | – | |

| 11. Not Publicc | −.13 | −.08 | .07 | .05 | .12 | −.14 | .33*** | .36*** | .18* | −.16* | – |

| M | .202 | .134 | .111 | .092 | .018 | .016 | 2.839 | 3.939 | .310 | 5.380 | .144 |

| SD | .403 | .230 | .315 | .116 | .043 | .028 | .381 | .340 | .885 | 1.284 | .352 |

Note. All table values are population estimates which account for the Add Health sampling strategy.

Black School: 0 = lower three quartiles of percent Black; 1 = top quartile percent Black.

Hispanic School: 0 = lower three quartiles of percent Hispanic; 1 = top quartile percent Hispanic.

Not Public: 0 = public; 1 = private or catholic.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

School-level achievement was measured using indicators of grades and test scores. While both grades and test scores have unique limitations as measures of school-level achievement (Hanushek & Taylor, 1990; Willingham, Pollack, & Lewis, 2002), the two measures together are better able to capture achievement at the school level (Clark & Watson, 1995). School-level grades were calculated by aggregating student reports of their GPA from the In-School Survey. School test scores, on the other hand, were taken from school administrator reports of the percentage of students testing above and below grade level. The percentage of students testing below grade level was subtracted from the percentage of students testing above grade level, yielding a measure of the extent to which there was a preponderance of students in a given school with high test scores. These two indicators of school-level achievement were then standardized and averaged (r = .46, p < .001). School size, and school type were based on school administrator reports of the size of the school (total student enrollment), and whether the school was public, private or catholic. The school size variable was log transformed to reduce right skewness/outliers, and a dichotomous variable was created for school type such that 1 indicated a school that was not public (i.e. private or catholic).

With respect to the percentage of Black students, a dichotomous school-level variable was created indicating a school in the top quartile with respect to the percentage of Black students. Of the 132 schools surveyed as part of the Add Health nationally representative sample, 33 fell into this category. These schools had student bodies with an average of 47% Black students (SD = 20.7). This variable therefore indicates schools where Black students are either the majority ethnic group in the school, or a substantial portion of the overall student body. The use of a dichotomous variable in this context is in line with the perspective that a critical mass of a particular group is necessary to change intergroup dynamics (Etzkowitz, Kernelgor, Neuschatz, Uzzi, & Alonzo, 1994). A second dummy variable was also created to indicate schools in the top quartile with respect to the percentage of Hispanic students. Twenty four schools fell into this category. These schools had an average of 42% Hispanic students (SD = 20.6). While continuous variables relating to the percentage of Black and Hispanic students in a school were also explored, we found that dichotomous variables were better able to capture differences between schools in social costs for particular groups. The indicator variables are therefore used in the analyses presented in this paper. All continuous variables were z-scored in the models presented.

Analysis Plan

Analyses for the current study involved multilevel modeling of individual and school-level variables (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Because Add Health data collection was school based, we included a random effect for school in each of our models as well as a random slope component for the relationship between grades and social acceptance. Including random effects allowed us to account for within-school clustering of the data and therefore to accurately assess the significance of model parameters. Multi-level models also allowed us to consider individual-level variables, school-level variables, and cross-level interactions simultaneously.

Four multilevel models were estimated to address questions relating to ethnic group differences in the relationship between achievement and social acceptance: model 1 focused on establishing the overall effect of GPA at Wave I on subsequent changes in social acceptance; model 2 tested whether this relationship differed across ethnic groups; and models 3 and 4 determined whether differences across groups could be explained by other individual and school-level factors. After establishing the relationship between grades and social acceptance for each ethnic group, the next model focused on testing whether immigrant status may be affecting social costs for particular ethnic groups. Specifically, model 5 considered whether Hispanic, Asian, or Black youth from immigrant families show less social costs with achievement than those from families with U.S. born parents. Model 6 then considered whether African American males experienced more social costs than females.

The last set of models focused on exploring potential school-level contingencies of the relationship between grades and social acceptance: model 7 looked at whether social costs for Black students were greater in schools with higher levels of achievement; model 8 looked at whether Black students in largely Black schools experienced less social costs than those in less Black schools; and finally, model 9 considered whether the effects of school achievement on social costs depended on the proportion of Black students in the school.

Similar models also tested the social consequences of achievement for Hispanic students as a function of school-level achievement and the percentage of Hispanic students in the school (models 10, 11, and 12). The effects of school context were also considered for individual Hispanic ethnic groups (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central/South American) and Asian ethnic groups (Chinese, and Filipino). Models 13, 14, and 15, for example, tested the effects of school contexts for adolescents from Mexican decent, and subsequent models tested context effects for the other Hispanic and Asian ethnic groups. Context effects could not be considered for Native Americans due to sample size limitations.

Because the Add Health sampling frame was stratified by various school characteristics, and because various subgroups of individuals were over-sampled, it was important to account for sample weights in all of our analyses. In addition to adjusting for the probability of selection at the level of both school and individual, sample weights also adjust for survey non-response between the Wave I and Wave II In-Home Interviews (Chantala & Tabor, 1999). This corrects for potential bias to the sample that may have been added with attrition between the first and second waves. All of the models presented in the current study are estimated using the gllamm procedure within Stata (Rabe-Hesketh, Pickles, & Skrondal, 2001; StataCorp, 2007).

Results

Descriptive Analysis and Correlations

All analyses presented in this paper account for the Add Health sampling strategy and are therefore representative of the adolescent population in the United States at the time the data was collected. Means differences were first considered across the different ethnic groups. Overall, ethnicity accounted for a significant portion of the variance in each of the variables considered. Ethnic group differences among individual-level variables are presented in Table 1.

Correlations between individual-level variables are presented in Table 2 along with estimated population means and standard deviations for each variable. All correlations above .02 are significant at the 95% confidence level. As expected, social acceptance was found to be positively correlated with GPA (r = .13, p < .001). Associations between school-level variables are presented in Table 3 along with estimated population means and standard deviations.

Multilevel Models

Longitudinal association between GPA and social acceptance

A series of models were estimated to address our hypotheses. Random effects for the intercept and slope were included in all models. Models 1 through 4 are presented in Table 4. Model 1 estimated the relationship between grades and social support controlling for individual-level covariates. Based on previous research (Chen et al., 1997; Wentzel, 1991, 2005), we expected that, on average, there would be a positive association between GPA and social acceptance. In line with our prediction, GPA at Wave I did significantly predict positive changes in social acceptance.

Table 4.

Multilevel Parameter Estimates Showing the Effects of GPA on Subsequent Changes in Social Acceptance as a Function of Ethnicity, Controlling for Individual and School-level Disadvantage

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | B(SE) | B(SE) | B(SE) | |

| Intercept | −.009(.021) | −.013(.022) | −.016(.022) | −.010(.024) |

| Level 1 Predictors: | ||||

| Social Accept. (Wave I) | .485(.013)*** | .484(.013)*** | .484(.013)*** | .483(.014)*** |

| Age | −.017(.007)* | −.017(.007)* | −.017(.007)* | −.018(.009)* |

| Male | .091(.025)*** | .090(.024)*** | .090(.024)*** | .090(.024) |

| Black | .008(.045) | .006(.043) | .008(.043) | .000(.048) |

| Hispanic | −.089(.046) | −.081(.048) | −.079(.048) | −.082(.048) |

| Asian | −.136(.058)* | −.124(.068) | −.120(.070) | −.125(.070) |

| Native | −.044(.106) | −.140(.110) | −.138(.110) | −.135(.112) |

| Mixed | −.108(.062) | −.099(.061) | −.097(.062) | −.099(.063) |

| Other | −.247(.145) | −.271(.149) | −.260(.148) | −.121(.148) |

| SES | .032(.012)* | .032(.012)** | .031(.012)* | .030(.013)* |

| Single Parent | −.061(.033) | −.059(.032) | −.061(.032)* | −.057(.032)* |

| GPA | .051(.014)*** | .070(.016)*** | .077(.017)*** | .092(.020)*** |

| Level 2 Predictors: | ||||

| SchSES | .015(.019) | |||

| SchSafety | .007(.023) | |||

| SchAchieve | −.001(.018) | |||

| Log Size | .001(.021) | |||

| Not Public | −.023(.042) | |||

| Level 1 Interactions: | ||||

| GPAxBlack | −.119(.042)** | −.112(.043)** | −.122(.042)** | |

| GPAxHispanic | −.007(.041) | .000(.042) | −.018(.045) | |

| GPAxAsian | −.034(.050) | −.040(.049) | −.059(.052) | |

| GPAxNative | −.291(.127)* | −.284(.130)* | −.309(.129)* | |

| GPAxMixed | .011(.064) | .013(.064) | −.001(.063) | |

| GPAxOther | .056(.125) | .052(.123) | .025(.121) | |

| GPAxSES | .008(.013) | .008(.014) | ||

| GPAxSingle Parent | −.025(.028) | −.030(.030) | ||

| Cross-Level Interactions | ||||

| GPAxSchSES | .001(.020) | |||

| GPAxSchSafety | −.015(.021) | |||

| GPAxSchAchieve | .019(.016) | |||

| GPAxLog Size | .005(.011) | |||

| GPAxNot Public | .063(.035) | |||

| Variance Components: | ||||

| Intercept | .0040(.0018)* | .0039(.0018)* | .0039(.0017)* | .0033(.0017)* |

| Slope (GPA) | .0064(.0019)*** | .0065(.0020)*** | .0064(.0020)*** | .0060(.0019)*** |

| Int-Slope Covariance | −.0031(.0011)** | −.0031(.0011)** | −.0029(.0013)** | −.0031(.0012)** |

| N(level 1) | 12,936 | 12,936 | 12,936 | 12,567 |

| N(level 2) | 132 | 132 | 132 | 127 |

Note. SchSES = school-level SES. SchSafety = school-level safety. SchAchieve = school-level achievement.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Several demographic variables were also found to be predictive of changes in social acceptance: males, higher SES adolescents, and younger adolescents all tended to have more positive changes in social acceptance over time. Additionally, Asians had less positive changes than Whites. The variance component associated with the random slope coefficient in model 1 was also found to be significant (p < .001). This suggests that the relationship between Wave I GPA and Wave II social acceptance does vary across schools, and provides justification for later models to look at school-level characteristics as moderators of this relationship.

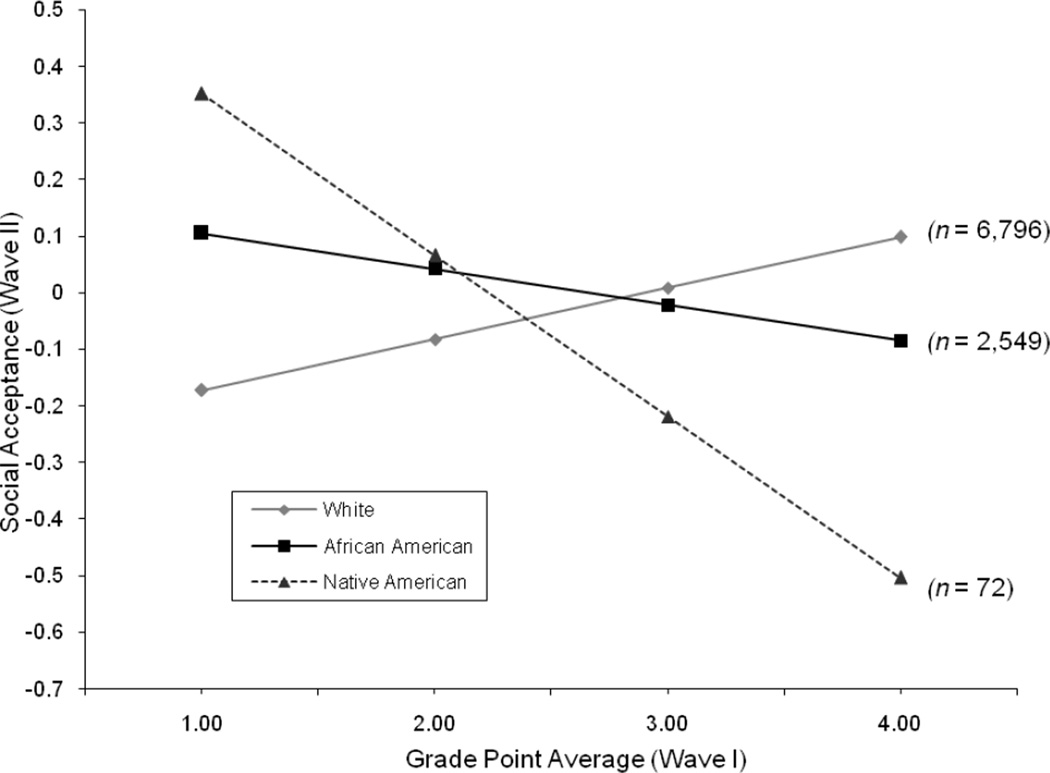

Ethnic-group differences in the relationship between GPA and social acceptance

Having established the direct association between GPA and social acceptance, model 2 added the GPA by race interaction terms in order to test for ethnic group differences in social costs with academic success. Parameter estimates for model 2 indicated that African American adolescents have a significantly weaker (more negative) relationship between GPA and social acceptance than Whites. Specifically, while Whites (the reference group in model 2) show a relatively strong positive association, the association for African Americans is negative, suggesting that there are differential social consequences with achievement for African Americans. While less Native Americans were present in the sample, as compared to Whites, they also showed significant social costs with achievement. Based on estimates from model 2, Figure 1 shows the effect of Wave I GPA on subsequent changes in social acceptance for Whites, African Americans, and Native Americans. Although the relationship between achievement and social acceptance was most negative for Native Americans, the difference between African Americans and Native Americans was not significant. Interaction terms for Hispanics and Asians in model 2 were not significant, suggesting that the relationship between grades and social acceptance for these groups tend, on average, to be the same as for Whites. In separate analyses, Hispanic and Asian sub-groups were also considered, but no differential social consequences were found.

Figure 1.

Fitted interaction plot depicting the relationship between Wave I GPA and Wave II social acceptance for Black, Native American, and White adolescents. Note. This figure is based on parameter estimates from model 2 (Table 4), with GPA converted back to its original four point scale.

Does disadvantage account for ethnic group differences in social costs?

Since African American and Native American adolescents are more likely than Whites to be from low-SES families, single-parent families, and disadvantaged schools, our next goal was determine whether the significant interaction effect for African Americans and Native Americans might be accounted for by controlling for individual and school-level disadvantage. Model 3 therefore added individual-level interactions (GPA × SES; GPA × Single Parent) as competing moderators and found that although the GPA × Black and GPA × Native terms decreased slightly (by 6% and 2%), both effects remained significant. Model 4 then controlled for the effects of school disadvantage on the relationship between grades and social acceptance. However, the GPA × Black interaction term remained highly significant, as did the GPA × Native term. Findings from these models suggest that individual and school-level factors do not account for the differential social costs with academic success found for African Americans and Native Americans.

Is immigrant status a key variable influencing social costs?

The next model considered whether less recent Hispanic, Asian, or Black immigrants show more social costs with academic success than their more recent immigrant counterparts. To test these effects, model 5 included three way interactions between GPA, race, and immigrant status. Parameter estimates for this model suggested that immigrant status did not play an important role for any of these groups. Specifically, with respect to the relationship between grades and social acceptance, Hispanic adolescents with foreign born parents (FBP) are not significantly different from Hispanic adolescents with U.S. born parents (GPA × Hisp. × FBP: B = −.080, SE = .115, p = ns). Asian and Black adolescents also showed no differences in social costs with respect to immigrant status (GPA × Asian × FBP: B = −.031, SE = .148, p = ns; GPA × Black × FBP: B = −.167, SE = .157, p = ns). Unrelated to hypotheses for the current study, we also inadvertently discovered, in model 5, that the main effect for Asians reported in model 1, suggesting greater decreases in social acceptance, is being entirely driven by the effect for Asians with foreign born parents (Asian × FBP: B = −.338, SE = .148, p < .05). This suggests that Asian adolescents growing up in families with foreign born parents (1st and 2nd generation) tend to be experiencing greater decreases in social acceptance across the adolescent period than Whites, while Asians adolescents from families with U.S. born parents (3rd generation or greater) do not show greater decreases.

Does the social costs effect depend on gender?

Model 6 tested for differences in social costs for African American males and females. Parameter estimates for this model suggest that no significant differences were present between males and females (GPA × Male × Black: B = .040, SE = .065, p = ns). Gender differences were also explored for each of the other ethnic groups and none were found to be significant. Models 5 and 6 (relating to immigrant status and gender) were not included as a table due to non-significant findings. A table detailing the parameter estimates for these models is available from the first author upon request.

School-level moderators of social costs for African Americans

The next set of models focused on exploring contingencies of the relationship between grades and social acceptance for African Americans. (Because of the small sample size for Native Americans, it was not possible to consider differences across schools for this group.) Models 7 through 9 are presented in Table 5. Model 7 focused on the interaction between GPA, Black race, and school-level achievement in order to determine whether being in a higher achieving school is associated with more social costs for African Americans. Results for this model suggested that, when considered alone, school-level achievement did not significantly affect the social costs of academic success for African Americans. Model 8 focused on the interaction between GPA, Black race, and Black school in order to determine whether being in a largely Black school might be protective against the social costs of academic success for African Americans. Results for this model also proved non-significant suggesting that, overall, the social costs of academic success for African Americans are not significantly different in largely Black schools.

Table 5.

Multilevel Parameter Estimates Showing the Effects of GPA on Subsequent Changes in Social Acceptance as a Function of Race, School-level Achievement, and the Proportion of Black Students in a School.

| Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | B(SE) | B(SE) | |

| Intercept | −.017(.023) | −.009(.023) | −.016(.024) |

| Level 1 Predictors: | |||

| Social Accept. (Wave I) | .483(.014)*** | .483(.014)*** | .483(.014)*** |

| Age | −.019(.007)* | −.017(.008)* | −.017(.007)* |

| Male | .090(.025)*** | .092(.025)*** | .092(.025)** |

| Black | .007(.045) | .019(.105) | .022(.086) |

| Hispanic | −.083(.048)* | −.081(.050) | −.083(.048) |

| Asian | −.124(.067) | −.120(.070) | −.124(.068) |

| Native | −.134(.111) | −.146(.110) | −.138(.112) |

| Mixed | −.097(.061) | −.100(.064) | −.010(.062) |

| Other | −.256(.149) | −.266(.149) | −.258(.149) |

| SES | .035(.012)** | .034(.012)** | .035(.012)** |

| Single Parent | −.053(.033) | −.054(.033) | −.051(.033) |

| GPA | .074(.017)** | .067(.018)*** | .072(.019)*** |

| Level 2 Predictors: | |||

| BlkSch | −.016(.038) | −.006(.036) | |

| SchAchieve | .017(.012) | .017(.013) | |

| Level 1 Interactions: | |||

| GPAxBlack | −.117(.044)** | −.182(.108) | −.155(.085)* |

| GPAxHispanic | −.015(.043) | −.011(.042) | −.011(.044) |

| GPAxAsian | −.037(.048) | −.047(.048) | −.040(.045) |

| GPAxNative | −.305(.123)* | −.293(.128)* | −.302(.123)* |

| GPAxMixed | .004(.064) | .005(.064) | .002(.064) |

| GPAxOther | −.048(.124) | .054(.126) | .048(.124) |

| Level 2 and Cross-level Interactions: | |||

| GPA*BlkSch | .033(.039) | .021(.036) | |

| GPA*SchAchieve | −.014(.012) | −.016(.012) | |

| Black*BlkSch | −.021(.119) | −.037(.103) | |

| Black*SchAchieve | −.043(.041) | −.046(.105) | |

| BlkSch*SchAchieve | .006(.036) | ||

| Black*BlkSch*SchAchieve | −.019(.115) | ||

| GPA*BlkSch*SchAchieve | .023(.040) | ||

| GPA*Black*BlkSch | .069(.118) | .059(.096) | |

| GPA*Black*SchAchieve | −.042(.032) | −.232(.098)* | |

| GPA*Black*BlkSch*SchAchieve | .222(.105)* | ||

| Variance Components: | |||

| Intercept | .0035(.0018)* | .0037(.0018)* | .0032(.0017)* |

| Slope (GPA) | .0068(.0020)*** | .0063(.0019)*** | .0064(.0019)*** |

| Int-Slope Covariance | −.0034(.0011)* | −.0030(.0013)* | −.0031(.0010)* |

| N(level 1) | 12,649 | 12,572 | 12,567 |

| N(level 2) | 128 | 128 | 127 |

Note. BlkSch = Black school (school in top quartile with respect to the percentage of Black students). SchAchieve = school-level achievement.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

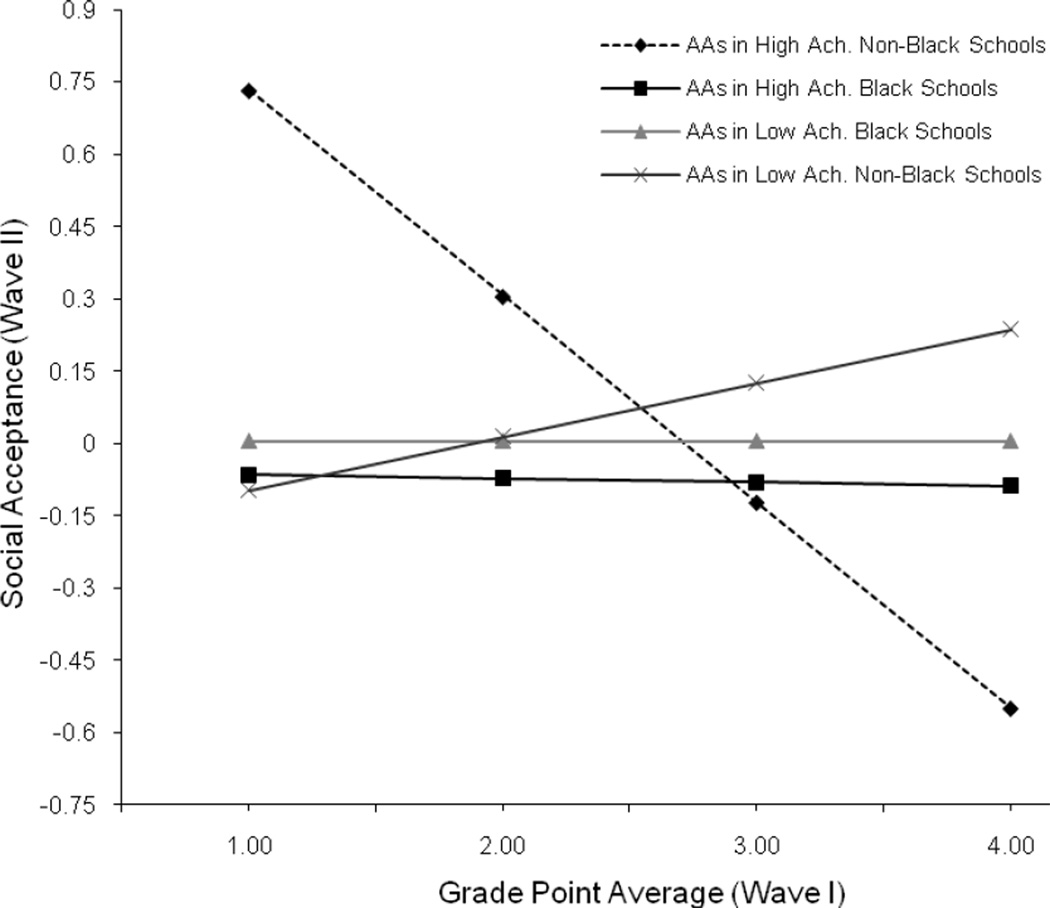

Model 9 focused on testing whether the effects of being in a high achieving school might depend on the proportion of Black students in the school, or in other words, whether it is important to consider school-level achievement and school racial context simultaneously. Parameter estimates from this model showed a significant interaction effect such that Black students in more high achieving schools had greater social costs, but only when the school had a smaller percentage of Black students. This model therefore suggests that a more Black school context is protective against social costs when the school is high achieving.

With respect to model parameters, because the Black school variable (BlkSch) is dummy code, the significant GPA × Blk × SchAch term in model 9 suggests that African American students in higher achieving non-Black schools have greater social costs with academic success than Black students in lower achieving non-Black schools (B = −.232, SE = .098, p < .05). The GPA × Blk × BlkSch × SchAch term shows that the increase in social costs due to being in a high achieving school is almost completely eliminated if the school is largely Black (B = .222, SE = .015, p < .05). In other words, African Americans in higher achieving (+1 SD on School-level achievement), less Black schools are experiencing the greatest social costs with academic success, whereas African Americans in high achieving Black schools are experiencing less social costs. Figure 2 illustrates the school-level findings for four groups of Black students: Black students in high-achieving non-Black schools; Black students in high-achieving Black schools; Black students in low-achieving non-Black schools; and Black students in low-achieving Black schools. The slopes of the lines for Black students in low-achieving Black and non-Black schools are not significantly different from each other, or from the slope of the line for Blacks in high-achieving Black schools. On the other hand, the slope of the line for Black students in high-achieving non-Black schools, is significantly different from the others, indicating that Black students in these schools, on average, experience the greatest social costs with achievement.

Figure 2.

Fitted interaction plot depicting the relationship between Wave I GPA and Wave II social acceptance for Black adolescents in four school contexts. Note. This figure is based on parameter estimates from model 9 (Table 5), with GPA converted back to its original four point scale. Sixty eight percent of Black students (n = 1,708) are in Black schools (top quartile of percent Black), and 32% percent (n = 801) are in less Black schools. Since school-level achievement is a continuous variable, specific sample sizes cannot be associated with each of the lines: High achieving school = +1 SD from mean, Low achieving school = −1 SD from mean. AAs = African Americans.

School-level moderators of social costs for Hispanic

Additional models focused on the effects of context for Hispanics as well as for specific Hispanic ethnic groups. Specifically, our first set of models looked at the social consequences of achievement for Hispanic students as a function of school-level achievement and the percentage of Hispanic students in the school. Results of these analyses (models 10, 11, and 12) suggested that school-level achievement and the proportion of Hispanic students in a school do not play a role for Hispanics.

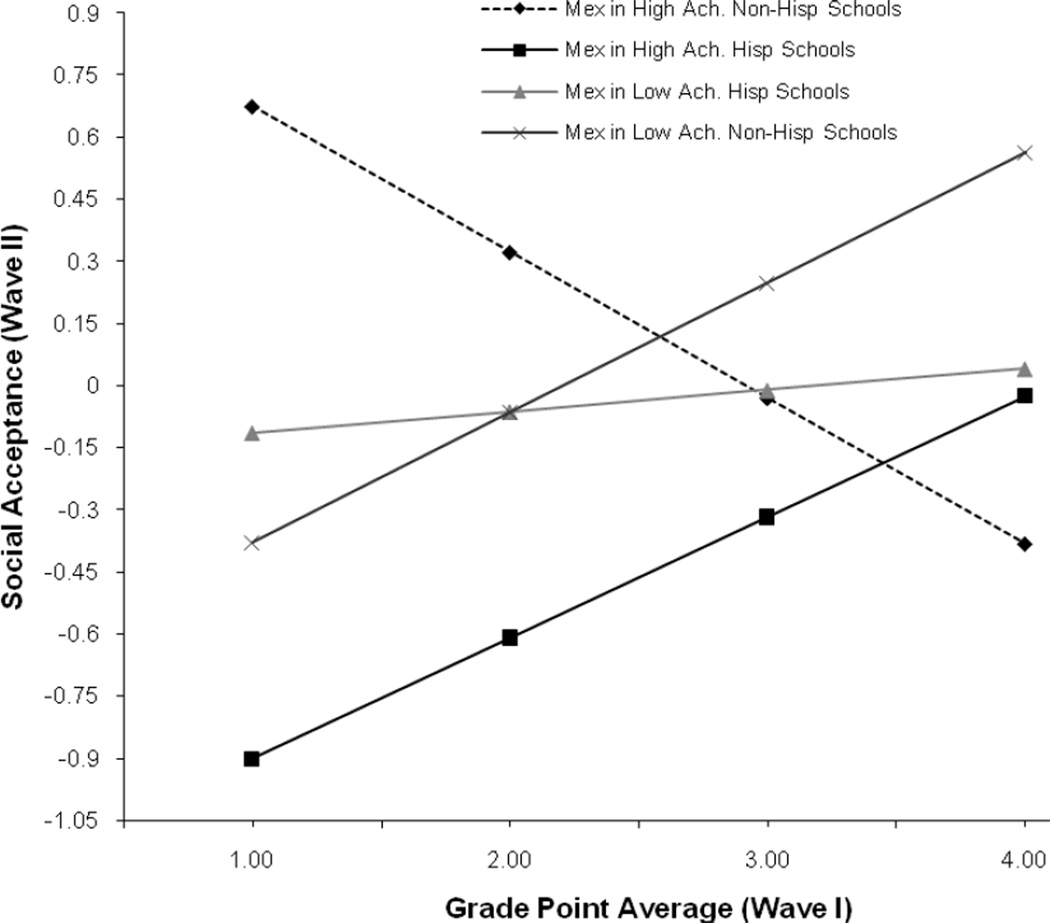

We then considered whether school characteristics may have differential consequences for the Hispanic sub-groups: Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central/South American. These analyses revealed that the school-context findings reported for Black students were replicated for Mexican students (models 13, 14, and 15). Tables of the full models are not included due to space limitations but are available from the first author upon request. Models 13 and 14 showed that school level achievement and the percentage of Hispanic students in the school, when considered separately, did not significantly moderate the relationship between achievement and social acceptance. However, when considered together, in model 15, the same findings emerged as for African American students. Specifically, model parameters showed that Mexican students experience greater social costs with achievement in high achieving schools (B = −.236, SE = .107, p < .05), but only when these schools do not have a substantial portion of Hispanic students (B = .277, SE = .109, p < .05). In other words, just as Black students experienced less social costs with achievement in higher achieving Black schools, Mexican students also experienced less social costs in higher achieving Hispanic schools. Figure 3 illustrates the school-level findings for students from Mexican decent. Specifically, Mexican students in higher achieving (+1 SD on School-level achievement) less Hispanic schools are shown to be experiencing the greatest social costs with achievement, whereas Mexican adolescents in other school contexts enjoy a positive association between achievement and social acceptance (as evidenced by the positive slopes for the other three lines). The slopes of the lines for Mexican students in low-achieving Hispanic and non-Hispanic schools are not significantly different from each other, or from the slope of the line for Mexican students in high-achieving Hispanic schools. On the other hand, as indicated above, the slope of the line for Mexican students in high-achieving non-Hispanic schools is significantly different from the others, indicating that Mexican students in these schools, on average, experience the greatest social costs with achievement.

Figure 3.

Fitted interaction plot depicting the relationship between Wave I GPA and Wave II social acceptance for adolescents from Mexican decent in four school contexts. Note. This figure is based on parameter estimates from model 15 (Table 6), with GPA converted back to its original four point scale. Seventy seven percent of Mexican students (n = 689) are in Hispanic schools (top quartile of percent Hispanic), and 23% percent (n = 207) are in less Hispanic schools. Since school-level achievement is a continuous variable, specific sample sizes cannot be associated with each of the lines: High achieving school = +1 SD from mean, Low achieving school = −1 SD from mean. Mex = Adolescents from Mexican decent.

Other Hispanic ethnic groups were also considered across school contexts. Findings for Puerto Rican, Central/South American, and Cuban adolescents were, however, quite different. The percentage of Hispanic students was found not to influence the social costs of achievement for any of these groups. Furthermore, school level achievement did not lead to increased social costs for any of these groups, regardless of whether or not the school was high achieving. In fact, for Puerto Rican and Central/South American adolescents school-level achievement was associated with less social costs (more social acceptance) with achievement (GPA × Puerto Rican × SchAchieve: B = .196, SE = .099, p < .05; GPA × Central/South American × SchAchieve: B = .124, SE = .045, p < .01).

In additional analyses, the relationship between achievement and social acceptance was considered for Black students as a function of the percentage of Hispanic students in the school and vice versa. No significant effects were found in these models, suggesting the importance of same-race minority peers, as opposed to minority peers in general. School context effects were also considered for Asians, but no significant differences were found. The percentage of Whites students in a school was also explored, but was not found to influence the effects of achievement on social acceptance for any of the groups considered.

Discussion

The current study explored the association between achievement and social acceptance across ethnic groups in order to test the proposition that some minority groups experience greater social costs with academic success. Furthermore, the effects of school-level variables on the relationship between achievement and social acceptance were examined. To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantitatively demonstrate differential social costs with academic success across ethnic group. In particular, results suggest that, as compared to Whites, Black and Native American adolescents experience more social costs with achievement, even after controlling for individual and school-level disadvantage. These findings are in line with work suggesting that greater social consequences may exist among currently stigmatized and historically oppressed groups (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Spencer & Harpalani, 2008; Steele, 1998).

An additional focus was to consider school-level contingencies. In particular, on the basis of existing work (e.g., Goldsmith, 2004), we explored school-level achievement and the proportion of same-race students in a school as moderators of the relationship between achievement and social acceptance. Findings suggested that the social costs of achievement were greater for African Americans in higher achieving schools, but only when these schools had a smaller proportion of Black students. Specifically, for Black students, the social consequences of achievement were most severe in higher achieving schools with less Black students. However, when schools did have a substantial percentage of same-race peers, the social costs were relatively low, regardless of the levels of achievement within the school (Figure 1).

Consistent with our hypotheses, these findings suggest that the social consequences of achievement for African Americans are largely contingent on context (Cross, 2003; Spencer et al., 2001), and therefore are not likely to be the result of a wide-spread cultural orientation in opposition to achievement. Furthermore, results are in line with research suggesting that inter-racial tensions are more pronounced in competitive or high achieving contexts (Brewer & Kramer, 1985), as well as with work suggesting that it is important for minority students to be exposed to a significant number of same-race peers (e.g., Goldsmith, 2004).

Our findings demonstrate that the greatest social costs with achievement for African American students are present in high achieving schools with a smaller proportion of Black students. However, the results also show that, for Black students in predominantly Black schools, the relationship between achievement and social acceptance is still not positive (see Figure 2). This is in contrast to a positive association between achievement and social acceptance for the majority group found in this study, as well as in previous work (Chen et al., 1997; Wentzel, 1991, 2005). The lack of positive association between achievement and social acceptance for African American adolescents in predominantly Black schools therefore suggests there are still some social costs with academic success for these students, relative to the majority group. This finding could be interpreted as in line with previous qualitative work conducted in predominantly Black schools (e.g. Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Fordham, 1988). However, because the relationship between achievement and social acceptance is more negative in competitive contexts, situational factors seem to be an important driving force behind this relationship.

The school-level findings for African Americans were also replicated for students from Mexican decent. Specifically, Mexican students experienced substantially more social costs in higher achieving schools, but only when these schools did not contain a substantial portion of Hispanic students (Figure 3). However, other Hispanic groups did not show equivalent trends. In fact, the percentage of Hispanic students in a school had no effects for the Cuban, Puerto Rican, or Central/South American groups. Additionally, school-level achievement had no effect for Cubans and had a different effect for adolescents from Puerto Rican and Central/South American decent than for Mexicans or Blacks. Specifically, higher achieving schools were associated with less social costs for Puerto Rican and Central/South American adolescents.

While this diversity in the social consequences of achievement among Hispanic groups was not predicted, a range of work is helpful in explaining these effects. Firstly, relating to Mexican Americans, a variety of research suggests that with respect to subordination and disenfranchisement, the history of Mexican-Americans is in many ways similar to that of Black Americans (Lopez & Stanton-Salazar, 2001; A. Portes & Rumbaut, 2001), and that the two groups are often similar in their reactions to discrimination (A. Portes, 1990). Given these perspectives, it is not surprising that Mexicans show similar tends to African Americans across school contexts. Several explanations are possible for the lack of social costs with achievement observed for Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Central/South American students across any of the contexts considered. Researchers have suggested that adolescents of Cuban decent tend to show fewer academic adjustment problems than those of Mexican decent (P. R. Portes, 1999). Additionally, most Cubans in our sample also tended to be in schools with a substantial portion of Hispanic students. With respect to Puerto Ricans, researchers have argued that their legal status as U.S. citizens may lead to less stigmatization and less problematic achievement dynamics than adolescents of Mexican decent (e.g., Flores-Gonzalez, 1999). Future work will be needed to test the various potential mechanisms behind the differential social costs experienced by particular groups. Overall, our findings are in line with the idea that acculturation experiences vary substantially across the individual ethnic groups within the Hispanic pan-ethnic category.

The current study also tested the possibility that immigrant status may be accounting for differences in social costs. Results of these analyses suggested that adolescents whose families have been in the United States for multiple generations did not show any greater social costs than their more recent immigrant counterparts. These findings, therefore, failed to provide support the idea that length of time in the U.S. accounts for differences in social costs across groups (A. Portes & Zhou, 1993; Spencer et al., 2003). Based on previous research (Osborn, 1997; Graham, Taylor, & Hudley, 1998), an additional hypothesis of the current study was that African American males might show greater social costs than females. Findings, however, showed no gender effect for African Americans, or for any of the other ethnic groups. This suggests that gender is not playing a direct role in the link between achievement and social acceptance.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the findings of this study suggest that differential social costs do exist for particular groups, it was not within the scope of this research to determine the detailed mechanisms for these effects. It will therefore be important for future studies to develop a more detailed understanding of group differences, especially in school contexts where discrepancies in social costs across groups were found to be most pronounced. Work in this area has suggested that some differences in achievement values are present during early adolescence (e.g., Graham, Taylor,& Hudley, 1998). However, the role of peer attitudes and norms in the relationship between achievement and social acceptance is less understood. It will therefore be useful for future work to explore these effects, as well as to examine contextual factors that may be influencing the achievement values of minority peer groups (e.g., stereotypes and discrimination from the majority group, or socialization messages from families and communities).

Another area of future research will be to explore the role of identity in the social costs of achievement. This is of particular importance given that racial and ethnic identity are thought to influence perceptions of racism, as well as its consequences. Furthermore, since differences in social costs across ethnic groups may be the result of attitudes and norms within peer groups, network techniques, which aggregate the characteristics of peers (e.g., Kiesner, Cadinu, Poulin, & Bucci, 2002), will be necessary to test these effects. Contextual factors such as socialization and experiences with discrimination will also be important to consider—particularly in relation to their role as predictors of group identity (Hughes et al., 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003).

Finally, it is unclear from the current study whether the social consequences of achievement experienced by particular groups come from same-race peers, from members of the dominant group, or from elsewhere. Distinguishing the source of social consequences with achievement will therefore be an important issue for future studies to address. It will be helpful to consider the possibility that greater social costs experienced by particular groups are the result of increased hostility from the majority group at higher levels of achievement. Specifically, given that research suggests that Whites direct their prejudice unequally, as a function of individual characteristics (Kaiser & Pratt-Hyatt, 2009), it is plausible that White adolescents may feel particularly threatened when members of specific groups achieve academically and therefore may express more hostility towards high achieving members of these groups. Future research will be necessary in order to distinguish these various possible sources of social costs.

Conclusion

In closing, we wish to emphasize that, although our findings indicate that ethnic group differences do exist, it is by no means our intention to insinuate that such differences are set in stone. Quite the opposite, our hope is that a more nuanced understanding of ethnic group differences, and the complex dynamics behind them, will stimulate actions to address these issues within education systems at multiple levels. While many researchers have argued for a color-blind perspective, suggesting that ethnic issues are irrelevant when background and contextual factors are considered (e.g., Cook & Ludwig, 1997; Rothstein, 2004), results of the current study suggest strongly otherwise. An important implication of this paper is therefore that, in order to redress ethnic gaps in achievement, in addition to focusing on socioeconomic and structural problems, schools and communities will need to understand and address issues of race.

Furthermore, while our results suggest that schools with more same-ethnic peers may be protective, we do not wish to imply that segregated schools are a necessity for minority students to maintain healthy social relations alongside academic achievement. We feel that a more appropriate implication of these findings is that schools with characteristics associated with differential social costs should seek to develop a greater awareness of unacknowledged stereotypes, and take additional measures to maintain healthy racial dynamics. Specifically, previous recommendations for school personnel to focus on earning and maintaining the trust of minority students, and to create an environment of “identity safety” (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005; Ogbu & Simons, 1998) may be of particular importance in high achieving schools where stigmatized minority groups are a clear minority.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth@unc.edu). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

References

- Ainsworth-Darnell JM, Downey DB. Assessing the oppositional culture explanation for racial/ethnic differences in school performance. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:536–553. [Google Scholar]

- Akom AA. Reexamining resistance as oppositional behavior: The Nation of Islam and the creation of a Black achievement ideology. Sociology of Education. 2003;76:305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M, Kramer R. The psychology of intergroup attitudes and behaviors. Annual Review of Psychology. 1985;36:219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology. 1993;99:353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH, Li D. Relation between academic achievement and social adjustment: Evidence from Chinese children. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:518–525. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantala K, Tabor J. Strategies to Perform a Design-Based Analysis Using the Add Health Data. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:309–319. doi: 10.1037/pas0000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Weighing the burden of “Acting White”: Are there race differences in attitudes towards education? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1997;16:256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Cavanagh S, Elder GH. Adolescent friendships as academic resources: The intersection of friendship, race, and school disadvantage. Sociological Perspectives. 2003;46:331–352. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. Shades of Black. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. Tracing the historical origins of youth delinquency and violence: Myths and realities about Black culture. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PG, Spencer SJ, Steele CM. Clearing the air: Identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women's leadership aspirations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz H, Kernelgor C, Neuschatz M, Uzzi B, Alonzo J. The paradox of critical mass for women in science. Science. 1994;266:51–54. doi: 10.1126/science.7939644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega W. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;4:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Gonzalez N. Puerto Rican High Achievers: An Example of Ethnic and Academic Identity Compatibility. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1999;10:343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S. Racelessness as a factor in Black students' school success: A pragmatic strategy or pyrrhic victory? Harvard Educational Review. 1988;58:54–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S, Ogbu JU. Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of ‘acting White’”. The Urban Review. 1986;18:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith PA. Schools’ racial, mix, students’ optimism, and the Black-White and Latino-White achievement gaps. Sociology of Education. 2004;77:121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Cauce AM, Friedman RJ, Mason CA. Family, peer; and neighborhood influences on academic achievement among African-American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:365–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02512027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Taylor A, Hudley C. Exploring achievement values among ethnic minority early adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:606–620. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty BMK, Patusky KL. Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research. 1995;44:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek EA, Taylor LL. Alternative assessments of the performance of schools: Measurement of state variations in achievement. Journal of Human Resources. 1990;25:179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnicracial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Crosnoe R, Elder GH. Students’ attachment and academic engagement: Role of race and ethnicity. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:318–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Pratt-Hyatt JS. Distributing prejudice unequally: Do Whites direct their prejudice toward strongly identified minorities? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:432–445. doi: 10.1037/a0012877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J, Cadinu M, Poulin F, Bucci M. Group identification in early adolescence: Its relation with peer adjustment and its moderator effect on peer influence. Child Development. 2002;73:200–212. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez D, Stanton-Salazar R. Mexican Americans: A second generation at risk. In: Rumbaut RG, Portes A, editors. Ethnicities: Children of immigrants in America. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2001. pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C, Fernandez SD, Girard B. The meaning of “Blackness”: How Black students differentially align race and achievement across time and space. In: Fuligni A, editor. Contesting stereotypes and creating identities: Social categories, identities and educational participation. New York: Russell-Sage; 2007. pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J. Beyond language: Ebonics, proper English, and identity in a Black-American speech community. American Educational Research Journal. 1999;36:147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J. Collective identity and the ‘burden of acting White’ in black history, community, and education. Urban Review. 2004;36:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu J, Simons HD. Voluntary and involuntary minorities: A cultural-ecological theory of school performance with some implications for Education. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1998;29:155–188. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne JW. Race and academic disidentification. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:728–735. [Google Scholar]

- Paige R. Paige calls achievement gap “major driver of racial inequity” in the United States. [Retrieved April 6,2008];U.S. Department of Education Press Release. 2004 from the World Wide Web: http://www.ed.gov/news/pressreleases/2004/07/07222004.html.

- Perie M, Moran R. NAEP 2004 Trends in Academic Progress: Three Decades of Student Performance in Reading and Mathematics (NCES 2005-464) Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2005. U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pong S. The school compositional effect of single parenthood on 10th-grade achievement. Sociology of Education. 1998;71:23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. From South of the Border: Hispanic Minorities in the United States. In: Yans-McLaughlin V, editor. Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 160–186. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1993;530:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Portes PR. Social and psychological factors in the academic achievement of children of immigrants: a cultural history puzzle. American Educational Research Journal. 1999;36:489–507. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Pickles A, Skrondal A. GLLAMM manual. London: University of London, Department of Biostatistics and Computing; 2001. (Tech. Rep. No. 2001/01) [Software manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. Class and schools: Using social, economic, and educational reform to close the black-White achievement gap. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity and factorial structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of an identity-focused cultural ecological perspective. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Cross WE, Jr, Harpalani V, Goss TN. Historical and developmental perspectives on Black academic achievement: Debunking the “acting White” myth and posing new directions for research. In: Yeaky CC, editor. Surmounting all odds: Education, opportunity, and society in the new millennium. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Harpalani V. What does “acting White” actually mean? Racial identity, adolescent development, and academic achievement among African American youth. In: Ogbu JU, editor. Minority status, oppositional culture and schooling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 543–601. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Markstrom-Adams C. Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development. 1990;61:290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Noll E, Stoltzfus J, Harpalani V. Identity and school adjustment: Questioning the “Acting White” assumption. Educational Psychologist. 2001;36:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. Stereotyping and its threats are real. American Psychologist. 1998;53:680–681. [Google Scholar]