Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether acetabular morphology may influence both pathogenesis and prognosis of the acetabular rim lesions and to propose a new system to classify labral tears.

Methods

We assessed radiographic and arthroscopic findings in 81 patients (40 male and 41 female patients, 86 hips) aged from 16 to 74 years (median, 31 years) who underwent hip arthroscopy.

Results

Acetabular rim lesions were associated with four different hip morphologies. Eleven (32 %) of 34 patients with severe rim lesions underwent hip arthroplasty for progressive symptoms, whereas no patient with early rim lesion reported significant progression of symptoms. The strategy of treatment was changed in 33 % of the patients undergoing arthroscopy before undertaking peri-acetabular osteotomy.

Conclusions

Hip arthroscopy avoids more invasive procedures in patients with early acetabular rim lesions.

Introduction

The features of ‘acetabular rim syndrome’ are still undefined, but the condition is common among patients with acetabular dysplasia following sub-optimal femoral head coverage. Increased shear stress to the acetabular margin may evolve into hypertrophy or tear of the labrum, or progress into degenerative changes, e.g. subchondral micro-fractures and sclerosis of the acetabulum occur in the early stages, cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis in the long term [1, 2].

A well-defined classification could be helpful to avoid misdiagnosis and underestimation of this pathology and better define the prognosis [3]. In the present study, we report on patients with acetabular rim lesions undergoing arthroscopy, and assess whether acetabular morphology is prognostic for the development of these lesions. Invasive open procedures such as peri-acetabular osteotomy have been widely used in the past to correct bony deformities and prevent degenerative changes. We wished to ascertain whether arthroscopic management of cartilage and labral injuries may avoid more invasive procedures in the short term, and prevent the occurrence of degenerative changes to the hip in the long term. We attempted to correlate imaging findings with arthroscopic findings for acetabular rim lesions and determine whether there is any prognostic significance. In addition, we proposed a new system to classify labral tears.

Methods

All procedures described in the present study were approved by the local ethics committee, and all patients gave their written consent to participate. Acetabular rim lesions were diagnosed in 81 (40 male and 41 female patients, 86 hips) of 193 patients who had undergone hip arthroscopy from 1996 to 2001. Age at surgery ranged from 16 to 74 years (median, 31 years). Patients were included if symptomatic, unresponsive to a six month application of conservative measures including physiotherapy and injections of hyaluronic acid and steroids, positive impingement test [2], and with evidence of labral tears at arthroscopy. We excluded patients with fractures and dislocations to the hip, with no labral tear at arthroscopy.

Radiographic assessment

Sixty-six patients underwent radiographic assessment. Several radiographic parameters were used to assess acetabular morphology. On radiographs, dysplasia was classified as type 1 (incongruent), type 2 (short roof), and normal [4]. The presence of an os acetabulare, acetabular cysts and pathological findings resulting from Perthes’ disease or sub-clinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis [5] was also assessed.

Arthroscopy

With the patient supine on the fracture table, a supratrochanteric lateral portal and an additional anterior portal were used. Under image intensifier control, gradual traction was applied to adequately distract the hip joint. We divided the acetabulum and femoral head into five and six sectors, respectively, to better define status and damage of labrum and cartilage. Labral tears were classified as radial flaps, longitudinal peripheral and unstable bucket handle lesions, with detachment from the acetabular bony rim. We used the classification by Outerbridge [6] to define the cartilage status: normal (grade 0), softening and swelling (grade 1), fragmentation or fissuration less than 1 cm (grade 2), fragmentation or fissuration more than 1 cm (grade 3), and erosion with exposition of the bone (grade 4). Debridement of cartilage and labral tears was performed in 80 hips (93 %) and microfractures in two hips (2 %). At arthroscopy, acetabular cysts were identified in 11 hips (13 %), cartilage and labrum lesions were treated in 31 patients who were candidates to receive a peri-acetabular osteotomy. The subchondral defects were filled with autologous bone graft or bone morphogenic protein (OP1, Stryker Biotech Bone Morphogenic Protein, Factor VII) under fluoroscopic guidance via an extra-articular percutaneus cannula after drilling from the lateral wall of the ilium.

Acetabular rim lesions were classified as early and severe. An early lesion presented softening and buckling of the antero-superior portion of the acetabular rim (Fig. 1), which progresses to labral and cartilage erosions (Figs. 2 and 3); successively, a cartilage flap may be observed (Figs. 4, 5 and 6). The femoral head is normal.

Fig. 1.

Arthroscopic photo showing buckling and softening of the articular cartilage on probing

Fig. 2.

The labral-articular junction lesion

Fig. 3.

Arthroscopic photo of bone exposure

Fig. 4.

Labral flap detachment

Fig. 5.

Lesion progression with the formation of an articular cartilage flap

Fig. 6.

MRI showing detachment of the labral articular cartilage and infiltration of joint fluid under the articular cartilage flap

Severe lesions evolve from the early ones, and present partial or full thickness defects, peri-articular or subchondral cysts (geodes) (Fig. 7). If a large articular cartilage flap is detached, the subchondral bone may be exposed more than 33 % of the distance between the rim and the superior ridge of the acetabular fossa (Fig. 8). In severe cases, the femur may also be involved, showing cartilage fibrillation, articular cartilage flap, and limited area of bare bone.

Fig. 7.

Arthroscopic photo of bare bone exposed after debridement of the flap

Fig. 8.

Severe acetabular rim lesion. Arthroscopic photo after debridement of the articular cartilage flap where bare bone is exposed over a distance of more than 33 % of the rim–fossa distance

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation were calculated for normal continuous data, versus median and ranges for the rest. Two-sample t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare parametric ordinal data; the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied to compare non parametric data, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazard models determined the effect of the imaging grading on the time between arthroscopy and hip arthroplasty. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Pre-operatively, patients were symptomatic (Table 1) for an average of 23 months (two to 198 months). Information on the type of trauma were available in 16 patients: 13 reported a low-velocity trauma twisting or exceeding the normal range of movement and three had a car or bicycle accident.

Table 1.

Presenting symptoms in patients with acetabular rim lesions

| Symptoms | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | 86 | 100 |

| Groin | 76 | 88 |

| Trochanteric region | 13 | 15 |

| Gluteal | 13 | 15 |

| Thigh | 1 | 1 |

| Limp | 22 | 26 |

| Catching, clicking | 24 | 28 |

| Stiffness | 13 | 15 |

| Instability | 4 | 5 |

Cartilage lesions to the acetabulum were diagnosed at arthroscopy in all 81 patients (86 hips): six grade 1 (7 %), 12 (14 %) grade 2, 20 (23 %) grade 3, and 48 (56 %) grade 4. Almost all patients with lesions of grades 2 and 3 presented full thickness articular cartilage flaps partially detached from the rim and bare bone beneath. A total of 68 (93 %) of 73 labral tears (Fig. 2) were degenerative, and the labrum was detached from the rim insertion; four (5 %) were longitudinal peripheral lesions, and one (1 %) was an unstable bucket handle tear. On the femoral side, cartilage lesions were noted in 19 (22 %) hips: three grade 1 (16 %), ten (53 %) grade 2, four (21 %) grade 3, and two (11 %) grade 4. Fifty-four (63 %) acetabular rim lesions were classified as early and 32 (37 %) as severe.

Hip morphology

Four main types of hip morphology were found on radiographs (Fig. 1): normal, type 1 dysplasia (incongruent), type 2 dysplasia (short roof) and post slip deformity (Table 2). The joint space was reduced (less than 2.5 mm) in three of 32 (10 %) patients with severe acetabular rim lesions and was normal in all patients with early lesions. The relationships between supposed risk factors and the severity of the acetabular lesion are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Factors associated with the different hip types

| Factors | Dysplasia type 1 (incongruent) | Dysplasia type 2 (short roof) | Normal radiographic parameters | Post slip deformity | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of hips | 14 (21 %) | 26 (39 %) | 19 (29 %) | 5 (8 %) | |

| CEA (centre edge angle of Wiberg), mean±SD | 14.9±7.3 | 23.8±5.4 | 31.0±3.5 | 33.2±1.6 | <0.001 |

| Acetabular angle, mean ±SD | 51.4±5.1 | 45.9 5.8 | 44.5±3.6 | 41.0±4.4 | <0.001 |

| Sourcil angle, mean ±SD | 17.3±7.1 | 8.4±4.6 | 5.2±3.0 | 2.6±4.0 | <0.001 |

| Roof angle, mean±SD | -4.4±10.2 | 5.2±6.4 | 8.9±2.7 | 8.4±3.6 | <0.001 |

| AF index, mean ±SD | 0.7±0.1 | 0.8± 0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | <0.001 |

| e-lat (horizontal distance between the apex of the teardrop sign and a vertical tangent to the medial most part of the femoral head) [mm], mean±SD | 14.9±3.7 | 13.6±2.2 | 12.8±3.7 | 11.0±3.6 | 0.19 |

| Cf-ca (distance between the centres of rotation of the femoral head the acetabulum) [mm], mean ±SD | 6.1±3.0 | 3.6±1.6 | 3.1±1.8 | 2.3± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Rf-ra (ratio of femoral head and acetabular radii), mean ±SD | 0.77±0.04 | 0.84±0.05 | 0.86±0.04 | 0.87±0.04 | <0.001 |

| Minimal joint space [mm], mean ±SD | 4.3± 0.8 | 4.3±0.7 | 3.8±0.9 | 3.5± 0.9 | <0.11 |

| Os acetabulare | 2 (14 %) | 1 (4 %) | 2 (10 %) | 2 (40 %) | 0.49 |

| Cyst | 1 (7 %) | 6 (23 %) | 5 (28 %) | 3 (60 %) | 0.33 |

a Overall comparisons were performed between incongruent, short roof and “normal radiographic parameters” patients. Post slip patients were excluded from these comparisons due to their small number and pathology originating from the femoral head

Table 3.

Factors associated with the severity of the acetabular rim lesions

| Factors | Acetabular rim lesion | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Severe | ||

| N | 54 | 32 | |

| Age [years]: median (range) | 30 (16–61) | 36.5 (19–74) | 0.01 |

| Duration of symptoms in months median (range) | 22 (2–192) | 25 (4–198) | 0.30 |

| Presence of a traumatic event, n (%) | |||

| Nil | 40 (74 %) | 30 (94 %) | 0.02 |

| Low and high velocity | 14 (26 %) | 2 (6 %) | |

| Hip type, n (%) | |||

| Incongruent | 7 (17 %) | 7 (29 %) | 0.13 |

| Short roof | 20 (50 %) | 6 (25 %) | |

| Normal radiographic parameters | 10 (25 %) | 9 (38 %) | |

| Post slip | 3 (8 %) | 2 (8 %) | |

| Radiographic measurements | |||

| Lateral CEA (centre edge angle of Wiberg), mean ± SD | 24.6 ± 7.3 | 25.1 ± 9.5 | 0.82 |

| Acetabular angle, mean ± SD | 46.4 ± 5.8 | 46.3 ± 5.5 | 0.92 |

| Roof obliquity, mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 6.6 | 8.8 ± 7.6 | 0.89 |

| Roof angle, mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 8.2 | 4.8 ± 8.9 | 0.65 |

| Rf_ra (ratio of femoral head and acetabular radii), mean ± SD | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Cf_ca (distance between the centres of rotation of the femoral head the acetabulum)[mm], mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 0.50 |

| e-lat (horizontal distance between the apex of the teardrop sign and a vertical tangent to the medial most part of the femoral head.) [mm], mean ± SD | 12.9 ± 3.0 | 14.2 ± 3.6 | 0.14 |

| AF index, mean ± SD | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 0.21 |

| Minimal joint space [mm], mean ± SD | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 0.07 |

| Presence of os acetabulare | 5 (12 %) | 6 (22 %) | 0.24 |

| Presence of subchondral cyst | 12 (26 %) | 9 (36 %) | 0.38 |

Survivorship analysis

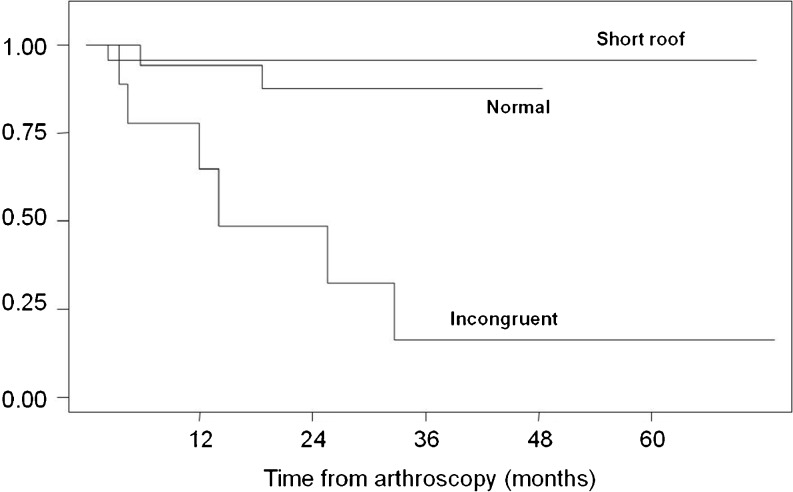

Six hips (43 %) with type 1 dysplasia (incongruent), one (4 %) with type 2 dysplasia (short roof), and two with normal morphology (11 %) underwent hip arthroplasty after a median interval time of eight, 20 and 24 months, respectively (Fig. 9), with worst prognosis (p = 0.002) for patients with type 1 dysplasia. Among patients with early acetabular rim lesions, 19 (35 %) returned to normal activity, 18 (33 %) declined to a lower sport activity level, 16 (30 %) were advised to undergo a peri-acetabular osteotomy, and one (2 %) to undergo a femoral derotational osteotomy. At a median follow-up of 24 months, no additional surgical procedures had been performed in hips which did not require further procedures. Of the 34 patients with increasing symptoms for severe acetabular rim lesions, 23 (68 %) continued to cope with their symptoms at a median 14-month follow-up, and 11 (32 %) underwent joint replacement at a median interval time of 11 months (range, one to 34 months) from arthroscopy. Severe and early acetabular rim lesions were significantly different in terms of survivorship (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 9.

Kaplan-Meier survival by hip morphology type

Fifteen (48 %) of the 31 patients who had undergone arthroscopy before undertaking a peri-acetabular osteotomy presented a severe acetabular rim lesion. Reviewed at six to 12 month intervals, six (40 %) of these underwent hip arthroplasty by a median follow-up time of 24 months from arthroscopy.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that dysplasia and symptoms are not necessarily associated with evidence of cartilage or labral lesions at arthroscopy. Conversely, deep degenerative changes may favour early detachment of the cartilage and progressive damage to the labrum. Therefore, the severity of the acetabular rim lesions may be of marked prognostic significance. Cartilage degeneration of the deeper layer is the primum movens of acetabular rim lesions [7], whereas hip congruency is involved in the short and mid-term progression of these lesions, as demonstrated by the higher (43 %) likelihood to undergo arthroplasty in patients with type 1 dysplasia than those with normal or type 2 dysplastic hips. At the latest assessment, patients with early acetabular rim lesions were still coping with their symptoms with no need for joint replacement, whereas 34 % of the patients with severe rim lesions had undergone joint replacement because of the progression of the symptoms. Acetabular rim lesions may occur in patients with no evidence of acetabular dysplasia (n = 26, 39 %) at imaging. Standard radiographs may not allow an early diagnosis in apparently normal hips. The synovial joint fluid may penetrate across the articular cartilage and progressively detaches the cartilage layers, producing a full thickness flap, often unrecognised at the early stages unless it is assessed with a probe [8]. Successively, when the labrum is detached and the subchondral bone exposed, the joint fluid is gathered in peri-articular or subchondral geodes [8]. Standard imaging may fail to diagnose isolated cartilage tears with no flap fragmentation because the full thickness flap, although detached from the acetabular rim, is maintained attached to the sub-chondral bone by the femoral head. When these flaps become unstable and the bone is exposed in weight bearing areas, the femoral head is progressively involved, and joint narrowing is visible at imaging, concomitantly to pain and clinical symptoms [7]. In non dysplastic hips, the impingement of the femoral neck against the acetabular rim may result, in the long term, in labral and articular cartilage degeneration [9, 10], whereas sub-clinical post-slip deformities [11], reduced femoral neck anteversion [12] or insufficient femoral head/neck offset [9] may produce femoral abnormalities. We found post-slip deformities of the femoral head in five patients, but MRI scans are not routinely performed to assess the femoral head-neck offset [9] or “the contour of the femoral head-neck junction” [10].

The evidence that high-level sport activity and repeated micro-trauma may predispose to develop intra-articular hip lesions [13, 14] and, in the long term, osteoarthritis [15, 16] was confirmed by the fact that nine of 19 acetabular rim lesions (47 %) observed in radiographically normal hips had occurred in high level athletes.

Peri-acetabular osteotomies are technically demanding, with a high morbidity rate [17–19]. Good and excellent results were observed at an average follow-up of 11.3 years in 73 % of patients who had undergone preservative joint procedures, with worse outcomes for older patients presenting labral tear and severe osteoarthritis [19]. In a study on 59 hips undergoing arthroscopy before peri-acetabular osteotomy [3], four patients, all with Outerbridge grade 4 lesions, developed severe osteoarthritis. We calculated the ratio between the size of the lesion and the distance from the acetabular margin to the superior portion of the acetabular fossa (i.e. “the weight bearing area”) to assess the size of the lesion. When the involved area exceeds one third of this distance, a re-directional peri-acetabular osteotomy could fail to laterally rotate the lesion [20], the zone of maximal weight bearing is still involved, subluxation is not corrected, and degeneration will continue. When facing with severe acetabular rim lesion, the chances of success after a periacetabular osteotomy are low. From the Kaplan-Meyer survival analysis by hip morphology type, 15 of the 31 patients originally considered suitable to receive a peri-acetabular osteotomy had severe acetabular rim lesions at arthroscopy, and six of them underwent joint replacement in the short term. Since imaging may not allow to define accurately the severity of the acetabular rim lesion, hip arthroscopy may be indicated before planning a peri-acetabular osteotomy [21–23].

A major strength of the present study is that a single, fully-trained experienced surgeon performed all the procedures. While a strength, this may limit generalisability of the finding, and the training and experience of the operating surgeon should be taken into account when undertaking this technically demanding procedure. Given the retrospective nature of the study, we are aware that the evidence is not as strong as that produced by a randomized controlled trial, and prospective investigations should focus on the outcomes following arthroscopy for management of early acetabular rim lesions.

Conclusion

Acetabular rim lesion and hip morphology may contribute to the development of early osteoarthritis. When the status of acetabular rim lesion and imaging are apparently normal, the assessment could be completed at arthroscopy, but further studies should be undertaken to define the pathological processes underlying the development of acetabular rim lesions, prevent the progression of these lesions, and the development of early degenerative changes.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Radin EL, Rose RM (1986) Role of subchondral bone in the initiation and progression of cartilage damage. Clin Orthop Relat Res 34-40 [PubMed]

- 2.Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:423–429. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasunaga Y, Ikuta Y, Kanazawa T, Takahashi K, Hisatome T. The state of the articular cartilage at the time of surgery as an indication for rotational acetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1001–1004. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B7.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitto RP, Klaue K, Ganz R, Ceppatelli S. Acetabular rim pathology secondary to congenital hip dysplasia in the adult. A radiographic study. Chir Organi Mov. 1995;80:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leunig M, Casillas MM, Hamlet M, Hersche O, Notzli H, Slongo T, Ganz R. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: early mechanical damage to the acetabular cartilage by a prominent femoral metaphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:370–375. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43-B:752–757. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy JC, Mason JB, Wardell SR. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular dysplasia: a pipe dream? Orthopedics. 1998;21:977–979. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19980901-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmalzried TP, Akizuki KH, Fedenko AN, Mirra J. The role of access of joint fluid to bone in periarticular osteolysis. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:447–452. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199703000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito K, Minka MA, 2nd, Leunig M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement and the cam-effect. A MRI-based quantitative anatomical study of the femoral head-neck offset. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:171–176. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.11092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:556–560. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B4.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoaglund FT, Steinbach LS. Subclinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Relationship to osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:142–143. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B1.9332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1747–1770. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in athletes: 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2140–2143. doi: 10.1177/0363546509337705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason JB. Acetabular labral tears in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:779–790. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Sarna S. Osteoarthritis of weight bearing joints of lower limbs in former elite male athletes. BMJ. 1994;308:231–234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6923.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindberg H, Roos H, Gardsell P. Prevalence of coxarthrosis in former soccer players. 286 players compared with matched controls. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:165–167. doi: 10.3109/17453679308994561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davey JP, Santore RF (1999) Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:33–37 [PubMed]

- 18.Hussell JG, Rodriguez JA, Ganz R (1999) Technical complications of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:81–92 [PubMed]

- 19.Siebenrock KA, Leunig M, Ganz R. Periacetabular osteotomy: the Bernese experience. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notzli HP, Muller SM, Ganz R. The relationship between fovea capitis femoris and weight bearing area in the normal and dysplastic hip in adults: a radiologic study. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2001;139:502–506. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papalia R, Buono A, Franceschi F, Marinozzi A, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome management: arthroscopy or open surgery? Int Orthop. 2012;36(5):903–914. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1443-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longo UG, Franceschetti E, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Hip arthroscopy: state of the art. Br Med Bull. 2010;96:131–157. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imam S, Khanduja V. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of femoroacetabular impingement. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]