SUMMARY

Background and Purpose

Genetic variation influences risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Hypertension (HTN) is a potent risk factor for ICH and several common genetic variants (SNPs) associated with blood pressure (BP) levels have been identified. We sought to determine whether the cumulative burden of BP-related SNPs is associated with risk of ICH and pre-ICH diagnosis of HTN.

Methods

Prospective multicenter case-control study in 2272 subjects of European descent (1025 cases and 1247 controls). Thirty-nine SNPs reported to be associated with BP levels were identified from the National Human Genome Research Institute GWAS catalog. Single-SNP association analyses were performed for the outcomes ICH and pre-ICH HTN. Subsequently, weighted and unweighted genetic risk scores were constructed using these SNPs and entered as the independent variable in logistic regression models with ICH and pre-ICH HTN as the dependent variables.

Results

No single SNP was associated with either ICH or pre-ICH HTN. The BP-based unweighted genetic risk score was associated with risk of ICH (odds ratio [OR] = 1.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.21, p=0.01) and the subset of ICH in deep regions (OR=1.18, 95%CI 1.07–1.30, p=0.001), but not with the subset of lobar ICH. The score was associated with a history of HTN among controls (OR=1.17, 95%CI 1.04–1.31, p=0.009) and ICH cases (OR=1.15, 95%CI 1.01–1.31, p=0.04). Similar results were obtained when using a weighted score.

Conclusion

Increasing numbers of high blood pressure-related alleles are associated with increased risk of deep ICH as well as with clinically identified HTN.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide stroke is the second leading cause of death and the leading cause of acquired disability.1 Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), the severest form of stroke, accounts for 15% of acute strokes in the United States. Despite advances in neurocritical care, more than 75% of patients will die or become severely disabled as a result of their ICH.2 Effective preventive and acute treatments are therefore urgently needed.

Hypertension (HTN) is a potent risk factor for ICH.3 This effect is strongest for ICH in deep hemispheric locations.4 HTN has also been associated with increased ICH volumes and worse clinical outcome.5,6 In recent years, genome-wide association studies have identified several common genetic variants (or Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms [SNPs]) associated with blood pressure (BP) levels.7–9 Each of these common genetics variants, however, exerts only a small effect on BP. Consequently, estimating the combined effect that all these SNPs produce may be the only way to determine whether these variants influence risk of ICH. Genetic risk scores (GRSs) can be implemented to obtain an aggregate measure of the burden of risk alleles related to high BP carried by each individual.10,11 This approach has already shown that larger burdens of risk alleles for high BP levels are associated with increased risk of stroke.9

Within the International Stroke Genetics Consortium’s (ISGC) ongoing genome-wide association study of ICH, we investigated the role of BP-associated SNPs on both ICH and pre-ICH diagnosis of HTN. We hypothesized that individuals with larger burdens of BP alleles will have an increased risk of ICH, specifically in deep locations of the brain. We also postulated that subjects with ICH carrying greater numbers of risk alleles for high BP should have an increased risk of HTN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patients

We utilized a multi-center case-control design for the outcomes HTN and ICH in subjects of self-reported European ancestry from the following ISGC studies: Hospital del Mar Intracerebral Hemorrhage study12 (HM-ICH) in Barcelona, Spain; the Jagiellonian University Hemorrhagic Stroke Study13 (JUHSS) in Krakow, Poland; the Lund Stroke Register14 (LSR) in Lund, Sweden; the Vall d’Hebron Hospital ICH Study15 (VHH-ICH), in Barcelona, Spain; the Medical University of Graz Intracerebral Haemorrhage study16 (MUG-ICH) in Graz, Austria; the Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Hemorrhagic Stroke4 (GERFHS) at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, USA; and the Genetics of Cerebral Hemorrhage on Anticoagulation (GOCHA) study17 in the USA (participating sites included Massachusetts General Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, and the Universities of Michigan, Virginia, Florida at Jacksonville, Washington and Utah).

All studies were approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee of participating institutions. All participants provided informed consent; when subjects were not able to communicate, written consent was obtained from their legal proxies.

Case ascertainment

Cases were enrolled according to methods previously described.18 ICH was defined as a new and acute (<24 hours) neurological deficit with compatible brain imaging showing the presence of intraparenchymal bleeding. Enrolled subjects were primary acute ICH cases that presented to the emergency department of participating institutions (all accredited stroke centers) who provided written consent, were > 18 years of age and had confirmation of primary ICH through neuroimaging (either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). Exclusion criteria included: anticoagulation, trauma, brain tumor, hemorrhagic transformation of a cerebral infarction, vascular malformation, or any other cause of secondary ICH. Additional recorded clinical characteristics included pre-ICH exposure to antiplatelet drugs or statins, history of ICH in a first-degree relative, and alcohol or tobacco use.

Ascertainment of ICH cases and assignment of hemorrhage location were performed by stroke neurologists at each ISGC site. ICH located in the cortex (with or without involvement of subcortical white matter) was defined as lobar, whereas ICH selectively involving the thalamus, internal capsule, basal ganglia, or brainstem was defined as deep. Cerebellar hemorrhages were also excluded from the study.

Control ascertainment

Controls were > 18 years of age and were enrolled from the same population that gave rise to the cases at each participating institution. Controls came from the same geographical area as the cases and two different sampling techniques were utilized for enrollment. For the GERFHS study, random digit dialing was implemented. For the remainder of the studies, controls were enrolled through ambulatory clinics. This last control sampling strategy can sometimes introduce selection bias. To assess this possibility the distribution of the bp-based GRS was compared between GERFHS (that used random digit dialing) and the rest of studies by means of ANOVA. Controls were confirmed to have no history of previous ICH by means of interview and review of medical records. Recorded clinical characteristics were identical to ICH cases.

Hypertension status

Cases and controls were considered to have hypertension when they (or their proxies) reported a medical history of HTN or were receiving anti-HTN medications at the time of admission with ICH. Several validation studies have shown that this approach has acceptable accuracy as compared to direct ascertainment of HTN through BP measurement.19–22

Procedures

Peripheral whole blood was collected from cases and controls at each participating institution at the time of consent. Blood samples were subsequently shipped to the Massachusetts General Hospital, the coordinating center, and genotyping was carried out at the Broad Institute. DNA was isolated from fresh or frozen blood, quantified with a quantification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and normalized to a concentration of 30 ng/μL. Genotyping was performed using Affymetrix 6.0 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) in GERFHS and Illumina 610k (San Diego, CA, USA) in the rest of the studies. Quality control procedures were implemented as described in Supplementary Figure 1. MACH software23 was utilized to impute unobserved SNPs based on reference panels from HapMap24 and the 1000-genomes project.25

Statistical analysis

Selection of SNPs associated with BP

SNPs associated with blood-pressure levels at p<1×10E-6 were selected from the National Human Genome Research Institute GWAS catalog.26 To ensure that the results of this study reflect independent effects, SNPs in each chromosome were pruned to avoid including variants in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.5.)

Population stratification

Assessment of the relation between each BP-associated SNP and risk of ICH or HTN was carried out after principal components analysis was implemented to account for population stratification.27 Principal components were initially applied to identify and remove population outliers, and subsequently entered as covariates in the regression models that were fit to test each hypothesis.

Genetic association analysis for individual variants

Single-SNP genetic association testing was completed within each sample using logistic regression, assuming additive effects for each risk allele present, and including age, gender and principal components 1 and 2 in the model. Results for individual samples were combined in meta-analysis using inverse-variance weighted, fixed effects meta-analysis.

Genetic risk score analysis

The main exposure of interest in the present study is the burden of risk alleles for increased BP, as expressed by a GRS. Both weighted GRS (wGRS) and unweighted GRS (uGRS) were calculated. A wGRS is the sum of the products of the risk allele count (0, 1 or 2) at each locus multiplied by the reported effect of that risk allele on BP. An uGRS is simply the sum of the risk alleles for BP across the selected loci. In both instances, for SNPs reported to have minor alleles that reduce BP, the risk allele was set to be the other (major) allele.

Association analysis for GRS

Multivariate logistic regression was used to model the risk of HTN or ICH, using age and gender as covariates. These covariates were included in the model for efficiency. In all models the GRS was converted to the standard normal distribution and entered as a continuous predictor. In this context, the beta for the GRS can be interpreted as the increase in risk of the outcome per 1 standard deviation (SD) increase of the GRS.

Additional analyses

Two additional association analyses involving GRSs were carried out, one excluding brainstem hemorrhages and the other adding principal components 1 and 2 as covariates in the model. To ascertain if the effect of the GRS on ICH was mediated through clinically observed HTN, the multivariate model described above for ICH was re-run entering HTN as a covariate. Finally, the same models were also implemented after stratifying by HTN status.

Statistical significance was considered to be Bonferroni-corrected p<0.001 and p<0.017 for single-SNP association analyses (39 tests) and GRS analyses (3 tests: all, deep and lobar ICH), respectively, all tests being two-sided. Genetic association testing for single variants, as well as score calculations were performed in PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/).28 All other statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC USA). Post-hoc power analysis showed that the study would achieve 90% power to detect a risk increase of 10% per additional SD of the GRS.

RESULTS

A total of 2,272 subjects were included in the study: 1025 ICH cases and 1247 ICH-free controls (mean[SD] age 71[±12], 48% female). Among cases, 521 (53%) had deep and 462 (47%) had lobar hemorrhages (Table 1). Fifty-two SNPs associated with BP levels were identified from the National Human Genome Research Institute GWAS catalog. After pruning to remove genetic variants in high linkage disequilibrium, 38 SNPs remained to be used in the GRS (Supplementary table 1). Tested independently in meta-analysis, no ingle SNP was associated with either HTN (Supplementary table 2) or ICH (Supplementary tables 3, 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Population characteristics by center.

| Multicenter, US

|

Barcelona, Spain

|

Krakow, Poland

|

Lund, Sweden

|

Cincinnati, US

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOCHA

|

HM-ICH + VVH-ICH

|

JUHSS

|

LSR

|

GERFHS

|

||||||

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| Subjects, n | 298 | 457 | 212 | 169 | 122 | 163 | 116 | 153 | 277 | 305 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 74 (10) | 72 (8) | 74 (11) | 71 (9) | 67 (12) | 65 (13) | 75 (10) | 75 (10) | 67 (15) | 66 (15) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 134 (45) | 231 (51) | 103 (49) | 77 (46) | 69 (57) | 93 (57) | 49 (42) | 69 (45) | 136 (48) | 138 (45) |

| Male | 164 (55) | 226 (49) | 109 (51) | 92 (49) | 53 (43) | 70 (43) | 67 (58) | 141 (55) | 209 (52) | 167 (54) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 217 (73) | 280 (61) | 126 (60) | 99 (64) | 96 (81) | 74 (45) | 76 (67) | 65 (43) | 169 (62) | 157 (52) |

| No | 81 (27) | 177 (39) | 83 (40) | 56 (36) | 23 (19) | 89 (55) | 38 (33) | 86 (57) | 142 (36) | 170 (48) |

| ICH type, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Lobar | 184 (58) | - | 88 (40) | - | 51 (39) | - | 36 (28) | - | 149 (41) | - |

| Deep | 114 (36) | - | 124 (56) | - | 71 (54) | - | 80 (62) | - | 128 (48) | - |

| Cerebellar | 18 (6) | - | 8 (4) | - | 9 (7) | - | 14 (10) | - | 36 (11) | - |

SD = standard deviation, ANOVA = analysis of variance, GERFHS = Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Hemorrhagic Stroke Study, GOCHA = Genetics of Cerebral Hemorrhage on Anticoagulation Study, HM-ICH = Hospital del Mar Intracerebral Hemorrhage Study, VVH-ICH = Vall d’Hebron Hospital ICH Study, LSR = Lund Stroke Register, JUHSS = Jagiellonian University Hemorrhagic Stroke Study.

The GRS was associated with a diagnosis of HTN among controls and among subjects with lobar hemorrhages (Table 2). Within controls, each additional SD of the GRS produced an increase in risk of HTN of 22% (odds ratio [OR]=1.22, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.08–1.37, p=0.001) and 17% (OR=1.17, 95%CI=1.10–1.31, p=0.009) for wGRS and uGRS, respectively (Table 2). Within cases with lobar ICH each additional SD of the GRS produced an increase in risk of HTN of 32% (OR=1.32, 95%CI 1.08–1.61, p=0.006) and 25% (OR=1.25, 95%CI=1.03–1.51, p=0.02; table 2), for wGRS and uGRS, respectively.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression results: Odds of pre-ICH HTN as a function of blood pressure-based GRS, age and gender.

| Covariate | ICH controls

|

ICH cases

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ICH

|

Deep ICH

|

Lobar ICH

|

||||||||||||||

| Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

|||||||||

| OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||||||||

| Score | 1.22 | 0.001 | 1.17 | 0.009 | 1.12 | 0.09 | 1.15 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.66 | 1.25 | 0.02 | 1.32 | 0.006 |

| (1.08–1.37) | (1.04–1.31) | (0.98–1.18) | (1.01–1.31) | (0.84–1.25) | (0.86–1.27) | (1.03–1.51) | (1.08–1.61) | |||||||||

| Age | 1.57 | <.0001 | 1.58 | <.0001 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 0.24 | 1.20 | 0.06 | 1.20 | 0.06 |

| (1.39–1.78) | (1.39–1.79) | (0.87–1.11) | (0.87–1.11) | (0.75–1.08) | (0.75–1.08) | (0.99–1.45) | (0.99–150) | |||||||||

| Gender | 1.04 | 0.73 | 1.05 | 0.69 | 1.40 | 0.01 | 1.41 | 0.01 | 1.45 | 0.07 | 1.15 | 0.06 | 1.27 | 0.22 | 1.28 | 0.21 |

| (0.83–1.31) | (0.83–1.32) | (1.08–1.81) | (1.08–1.82) | (0.98–2.20) | (0.97–2.2) | (0.87–1.85) | (0.87–1.86) | |||||||||

OR = Odds ratio, CI = Confidence interval, GRS = Genetic risk score.

The GRS was associated with risk of all (deep and lobar) and deep ICH, but not with lobar ICH (Table 3). When considering all (deep and lobar) ICH cases, each additional SD of the GRS produced an increase in risk of ICH of 10% (OR=1.10, 95%CI=1.01–1.19, p=0.03) and 11% (OR=1.11, 95%CI=1.02–1.21, p=0.01, table 3), for wGRS and uGRS, respectively. When including only deep hemorrhages in the analysis, each additional SD of the GRS produced an increase in risk of ICH of 15% (OR=1.15, 95%CI=1.04–1.27, p=0.008) and 18% (OR=1.18, 95%CI=1.07–1.30, p=0.001; table 3), for wGRS and uGRS, respectively. These results remained unchanged when excluding brainstem hemorrhages and when adding principal components 1 and 2 to the model.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression results: Odds of ICH as a function of blood pressure-based GRS, age and gender.

| Covariate | All ICH

|

Deep ICH

|

Lobar ICH

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

Weighted GRS

|

Unweighted GRS

|

|||||||

| OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||||||

| Score | 1.10 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 0.008 | 1.18 | 0.001 | 1.05 | 0.34 | 1.05 | 0.34 |

| (1.01–1.19) | (1.02–1.21) | (1.04–1.27) | (1.07–1.30) | (0.95–1.17) | (0.95–1.17) | |||||||

| Age | 1.09 | 0.04 | 1.09 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.59 | 0.97 | 0.55 | 1.27 | <0.001 | 1.27 | <0.001 |

| (1.01–1.19) | (1.01–1.19) | (0.88–1.07) | (0.87–1.07) | (1.14–1.43) | (1.14–1.43) | |||||||

| Gender | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.65 | 1.05 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.35 |

| (0.85–1.18) | (0.85–1.18) | (0.86–1.28) | (0.86–1.28) | (0.74–1.12) | (0.74–1.11) | |||||||

OR = Odds ratio, CI = Confidence interval, GRS = Genetic risk score.

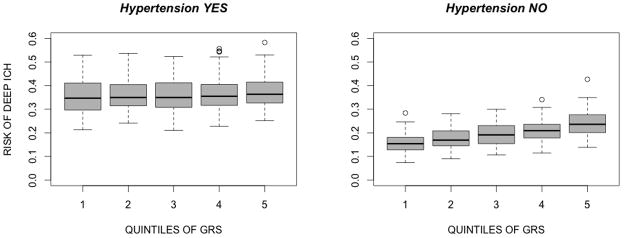

The association between the GRS and ICH appears to be stronger in non-hypertensives (Table 4 and Figure 1). When stratifying by HTN status, the effect of the GRS remained present within deep ICH in non-hypertensives (per increase in 1 SD of the uGRS OR=1.25, 95%CI 1.06–1.50, p=0.007), but not in hypertensives (per increase in 1 SD of the uGRS OR=1.1, 95%CI 0.97–1.25, p=0.14). No effect was observed within HTN strata for all and lobar ICH. When incorporating HTN into the model, the strength of the association was not substantially modified (supplementary table 6).

Table 4.

Increase in risk of ICH per additional SD of the unweighted GRS, stratifying by HTN.

| Stratifying Covariate | All ICH

|

Deep ICH

|

Lobar ICH

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Hypertension NO | 1.1 | (0.96–1.26) | 0.16 | 1.26 | (1.06–1.50) | 0.007 | 1.04 | (0.89–1.21) | 0.59 |

| Hypertension YES | 1.08 | (0.97–1.22) | 0.13 | 1.1 | (0.97–1.25) | 0.14 | 1.07 | (0.93–1.25) | 0.31 |

OR = Odds ratio, CI = Confidence interval, GRS = Genetic risk score

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of deep ICH by quintiles of the unweighted GRS, stratifying by HTN status.

The x-axis represents predicted probabilities of deep ICH, modeling the score linearly and including age and gender in the model. The y-axis shows categorization based on quintiles of the GRS. Left panel: hypertensives. Right panel: non-hypertensives.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that the burden of risk alleles for BP is associated with risk of ICH. We also show that, as expected, the GRS is associated with clinically identified HTN. In line with previous findings suggesting differences in underlying biology between deep and lobar ICH,29 the association between the GRS and risk of ICH appears to be driven by ICH in deep regions of the brain. This association remained significant even when HTN was incorporated into the model, a finding that raises the possibility of misclassification of HTN status, given that self-report and medication intake, and not actual BP levels, were utilized to ascertain this status.

This is the first demonstration that genetic variants for BP also influence risk of ICH. These findings build on previous reports demonstrating the feasibility of applying GRSs to stroke. A mitochondrial genome wide association study of ischemic stroke described a relation between a GRS generated with mitochondrial variants and risk of ischemic stroke.30 Our results also complement the conclusions of a recent report that specifically looked into the role of the genetics of hypertension in stroke. This report was a subanalysis of a large meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of BP9 and found an association between the aggregate burden of BP variants and stroke. In that study, however, the effect of the BP-associated GRS was not assessed for ICH, or for ICH subtypes.

Deep ICH has been primarily attributed to the effects on the cerebral vessels of long-standing hypertension, while a substantial proportion of lobar ICH appears to arise in the setting of amyloid angiopathy. In the present study, the association between the BP-based GRS and ICH was restricted to deep ICH cases. Furthermore, the association for deep ICH was predominantly observed in subjects who had not been labeled as hypertensives. One explanation could be that the GRS captured increases in risk of ICH produced by BP levels that are below those currently used to establish a diagnosis of HTN. Given the limitations of the approach implemented in the study to ascertain HTN, a second possibility is that subjects labeled as non-hypertensives in this population were misclassified.

These data have important implications for risk prediction for ICH. Given the limited impact of acute treatments for ICH, identifying subjects at highest risk of sustaining an ICH is of paramount importance, as it would open the possibility of implementing aggressive preventive strategies in high-risk individuals. Genetic variants can aid in this goal, as these data are available from birth, long before hypertension is diagnosed, are constant over time, and are not subject to misclassification, and can be collected quickly, cheaply and painlessly. Importantly, this same approach could be applied to other risk factors and intermediates, and combined genetic data on common variants for these intermediates could be used to build increasingly precise risk prediction models.

With regard to future research directions, our results demonstrate that, considered in isolation, no single variant related to HTN is associated with ICH. Indeed, it is the aggregate burden of these variants that, in the end, increase the risk of suffering an ICH. Future investigations can leverage this finding and test if genetic variation affecting entire biologic pathways known to influence BP influence risk of ICH. Furthermore, this same approach may be applied to other biologic processes and risk factors known to play a role in ICH, like hypercholesterolemia, alcohol abuse, smoking and obesity.

The present study was undertaken within the largest sample assembled of ICH cases with available genome-wide data. In addition, the collection of clinical data and biological samples was done following standardized, pre-specified guidelines at every participating site, and stroke neurologists and neuroradiologists ascertained the cases and described important phenotypic characteristics, including ICH location. These last two features combined greatly decrease the possibility of outcome misclassification. This is particularly important in the field of stroke, where misclassification of stroke subtypes is usually a limitation.

A number of limitations in the study should be addressed. First, the fact that some of the controls were selected in ambulatory clinics introduces the possibility of selection bias. This would be important because the proportion of hypertensive controls could be higher using this sampling scheme, with a consequent increase in the presence of SNPs associated with hypertension among controls. It should be noted, however, that this situation, if anything, would bias the results towards the null. Additionally, the distribution of the GRS in controls enrolled by GERFHS, a study that implemented random-digit dialing, was similar to that observed in controls enrolled by studies that applied a sampling scheme based on ambulatory clinics (data not shown). Second, selection bias could also be present in the form of survival bias. Patients picked up in the setting of a case-control design would be those who survived the onset of an ICH, thus reaching the hospital and allowing for their enrollment. As has been shown recently, however, simulation results suggest that the effect on risk estimates introduced in this setting would be relatively small.31

SUMMARY

In conclusion, we show that an association exists between the burden of risk alleles for elevated BP and the risk of deep ICH. This association is stronger for those individuals labeled as non-hypertensives. Further research is needed to evaluate the clinical value of this genetic risk score.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

FUNDING AND SUPPORT

All funding entities had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, writing of the report and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

DECIPHER: This study is funded by NIH-NINDS grant 5U54NS057405 (DECIPHER).

Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Hemorrhagic Stroke: This study was supported by NIH grants NS36695 (Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Hemorrhagic Stroke) and NS30678 (Hemorrhagic and Ischemic Stroke among Blacks and Whites) and by the Greater Cincinnati Foundation Grant (Cincinnati Control Cohort).

Genetics Of Cerebral Hemorrhage on Anticoagulation: This study was funded by NIH-NINDS grants R01NS059727, the Keane Stroke Genetics Research Fund, the Edward and Maybeth Sonn Research Fund, by the University of Michigan General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR000042) and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources. Drs. Biffi and Anderson were supported in part by the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research (0775010N).

Hospital del Mar ICH study: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo de España, Instituto de Salud Carlos III with the grants: “Registro BASICMAR” Funding for Research in Health (PI051737); “GWALA project (PI10/02064)”; Grant from Spanish Research Networks “Red HERACLES” (RD06/0009). FEDER.

Jagiellonian University Hemorrhagic Stroke Study: This study is supported by a grant funded by the Polish Ministry of Education (N N402 083934).

Lund Stroke Register: Lund University, Region Skåne, the Swedish Research Council (K2010-61X-20378-04-3), the Freemasons Lodge of Instruction EOS in Lund, King Gustav V and Queen Victoria’s Foundation, Lund University, the Department of Neurology Lund, and the Swedish Stroke Association. Biobank services and genotyping were performed at Region Skåne Competence Centre (RSKC Malmö), Skåne university hospital, Malmö, Sweden.

Medical University of Graz ICH Study: Controls of the MUG-ICH study are from the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study (ASPS), a population-based study funded by the Austrian Science Fond (FWF) grant number P20545-P05 and P13180. The Medical University of Graz supports the databank of the ASPS.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373:1632–1644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brott T, Thalinger K, Hertzberg V. Hypertension as a risk factor for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1986;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo D, Sauerbeck LR, Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Szaflarski JP, Gebel J, et al. Genetic and environmental risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage: preliminary results of a population-based study. Stroke. 2002;33:1190–1195. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014774.88027.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qureshi AI. Acute hypertensive response in patients with stroke: pathophysiology and management. Circulation. 2008;118:176–187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vemmos KN, Tsivgoulis G, Spengos K, Zakopoulos N, Synetos A, Manios E, et al. U-shaped relationship between mortality and admission blood pressure in patients with acute stroke. J Intern Med. 2004;255:257–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiura Y, Tabara Y, Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Miki T, Tomoike H, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension-related phenotypes in a Japanese population. Circ J. 2010;74:2353–2359. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehret GB. Genome-Wide Association Studies: Contribution of Genomics to Understanding Blood Pressure and Essential Hypertension. Current Hypertension Reports. 2010;12:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison AC, Bare LA, Chambless LE, Ellis SG, Malloy M, Kane JP, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease risk using a genetic risk score: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:28–35. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hivert M-F, Jablonski KA, Perreault L, Saxena R, McAteer JB, Franks PW, et al. Updated genetic score based on 34 confirmed type 2 diabetes Loci is associated with diabetes incidence and regression to normoglycemia in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes. 2011;60:1340–1348. doi: 10.2337/db10-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomis M, Ois A, Rodríguez-Campello A, Cuadrado-Godia E, Jiménez-Conde J, Subirana I, et al. Outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage patients pre-treated with statins. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:443–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pera J, Slowik A, Dziedzic T, Pulyk R, Wloch D, Szczudlik A. Glutathione peroxidase 1 C593T polymorphism is associated with lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:445–449. doi: 10.1159/000126918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallström B, Jonssön A-C, Nerbrand C, Norrving B, Lindgren A. Stroke incidence and survival in the beginning of the 21st century in southern Sweden: comparisons with the late 20th century and projections into the future. Stroke. 2008;39:10–15. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domingues-Montanari S, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Mendioroz M, Boada M, Munuera J, et al. ACE variants and risk of intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence in amyloid angiopathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:551.e13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert T, Lechner A, Flooh E, Schmidt H, Schmidt R, Fazekas F. Lack of association of lobar intracerebral hemorrhage with apolipoprotein E genotype in an unselected population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:266–270. doi: 10.1159/000091225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genes for Cerebral Hemorrhage on Anticoagulation (GOCHA) Collaborative Group. Exploiting common genetic variation to make anticoagulation safer. Stroke. 2009;40:S64–S66. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biffi A, Sonni A, Anderson CD, Kissela B, Jagiella JM, Schmidt H, et al. Variants at APOE influence risk of deep and lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:934–943. doi: 10.1002/ana.22134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada K, Yatsuya H, Ouyang P, Otsuka R, Mitsuhashi H, Takefuji S, et al. Self-reported medical history was generally accurate among Japanese workplace population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:894–900. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso A, Beunza JJ, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Martínez-González MA. Validation of self reported diagnosis of hypertension in a cohort of university graduates in Spain. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas CM, Burt VL, Gillum RF, Pamuk ER. Validity of self-reported hypertension in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988–1991. Prev Med. 1997;26:678–685. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Consortium T1000 GP. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hindorff LA, MacArthur J, Wise A, Junkins HA, Hall PN, Klemm AK, et al. [Accessed [Accessed January 25, 2012]];A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. Available at: www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

- 27.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns JD, Manno EM. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage: update on epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment strategies. Compr Ther. 2008;34:183–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson CD, Biffi A, Rahman R, Ross OA, Jagiella JM, Kissela B, et al. Common mitochondrial sequence variants in ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:471–480. doi: 10.1002/ana.22108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson CD, Nalls MA, Biffi A, Rost NS, Greenberg SM, Singleton AB, et al. The effect of survival bias on case-control genetic association studies of highly lethal diseases. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:188–196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.