Abstract

Background

Current guidelines do not define the lower severity threshold for thrombolysis. In this study, we describe the variability of treatment of mild stroke patients across a network of academic stroke centers.

Methods

Stroke centers within the Specialized Program of Translational Research in Acute Stroke (SPOTRIAS) prospectively collect data on patients treated with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV rt-PA), including demographics, pretreatment National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, and in-hospital mortality. We examined the variability in proportion of total tissue plasminogen activator–treated patients in the NIHSS categories (0–3, 4–5, or ≥6) and associated outcomes.

Results

A total of 2514 patients with reported NIHSS scores were treated with IV rt-PA between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. The proportion of patients with mild stroke (NIHSS scores of 0–3) who were treated with IV rt-PA varied substantially across the centers (2.7–18.0%; P <.001). There were 5 deaths in the 256 treated with an NIHSS score of 0–3 (2.0%). The proportion of treated patients across the network with an NIHSS score of 0 to 3 increased from 4.8% in 2005 to 10.7% in 2009 (P = .001).

Conclusions

There is substantial variability in the proportion of treated patients who have mild stroke across the SPOTRIAS centers, reflecting a paucity of data on how to best treat patients with mild stroke. Randomized trial data for this group of patients are needed to clarify the use of rt-PA in patients with the mildest strokes.

Keywords: Mild stroke, stenosis

Despite the clear benefit of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV rt-PA) for acute ischemic stroke,1 few patients receive it.2 The most common exclusions are arriving outside of the time window,3 followed by presenting with rapidly improving symptoms or mild syndrome.4 In the original National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) trial, participants with a minor or rapidly improving syndrome were excluded, 1 leading to its adoption as a common exclusion criterion for thrombolysis. The trial defined this exclusion criterion as rapidly improving symptomsor isolated focal neurologic deficits (sensoryloss, ataxia, facial weakness, or dysarthria).5 “Minor neurologic deficit” and “rapid improvement” are loosely defined by current treatment guidelines6,7 and have variable definitions in research reports.8–11 A deficit measured on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of ≤ 3 or 5 are the most commonly used definitions. Several case series have reported poor outcomes in patients with mild stroke who are not treated with IV rt-PA.9,11,12

The lack of clinical consensus and randomized clinical trial data on how to best treat patients with mild stroke may lead to variability between and within stroke centers as to whether these patients should be treated with recanalization therapy. Reasons for this variability may include tolerability for treating stroke mimics, treatment of deficits not captured by the NIHSS, or use of multimodality neuroimaging to identify patients who may be at risk for worsening. The aim of this study was to examine this variability across the Specialized Program of Translational Research in Acute Stroke (SPOTRIAS) network.

Methods

Demographic, social, and clinical data from hospitalized stroke patients were collected by review of the medical record and patient encounters as part of SPOTRIAS at all the participating centers. SPOTRIAS is a program funded by the National Institutes of Health consisting of 8 academic stroke centers with a central aim of testing novel stroke treatments in the phase I and II stages (see Acknowledgements for a list of participating centers and primary investigators). Each SPOTRIAS center is required to establish and maintain a stroke patient database that includes information on all acute stroke clinical trials and all stroke patients who received acute stroke treatments. Complete data collection was performed on consecutive patients who were treated with IV rt-PA or another recanalization strategy, including those treated via telemedicine or at affiliated hospitals. Data were not available for patients who were treated with IV rt-PA for whom consent was not obtained or for whom there was not a waiver of consent, and in some patients who were treated with IV t-PA at a referring hospital of the comprehensive stroke center. Collected data elements included pretreatment NIHSS score, treatment with IV rt-PA or other recanalization strategies, discharge disposition, age, race/ethnicity, and sex. The analyses are limited to patients arriving within 3 hours of onset who received IV rt-PA. Ninety-day clinical outcomes and information regarding symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH) and modified Rankin Scale score were available in only a limited number of patients. Data were sent to an external data repository company on a quarterly basis.

For this analysis, we defined 3 categories of stroke severity based on the pretreatment NIHSS score: 0 to 3,13,14 4 to 5,15 and ≥6. Our primary hypothesis was that there would be significant variability in the proportion of patients treated with IV rt-PA in the NIHSS 0 to 3 and 4 to 5 categories between centers. Continuous variables were compared using a 2-sided t test, while proportions were compared using a Chi-square statistic. All analyses were carried out with SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the SPOTRIAS centers.

Results

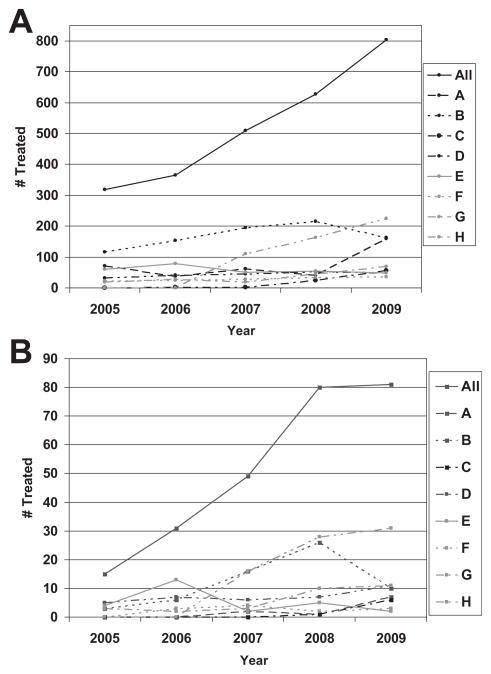

A total of 2626 patients were treated with IV rt-PA within 3 hours of stroke onset across SPOTRIAS centers between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. Pretreatment NIHSS scores were available in 2514 patients, of whom 535 (21.3%) had a mild stroke (NIHSS ≤5). All mild strokes were treated with IV rt-PA as the only recanalization therapy. For the entire cohort, the mean age was 67.6 ± 15.5 years, and 49.5% were women; 19.1% were non-Hispanic black and 11.1% were Hispanic. Baseline demographics are summarized in Table 1. The average age, proportion of women, and median NIHSS scores were similar across the entire SPOTRIAS network. Over the observation period, more patients across all NIHSS categories were treated with IV rt-PA (Fig 1A) and in the NIHSS 0 to 3 category (Fig 1B).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis in the SPOTRIAS network with an available National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score

| All | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of treated patients | 2514 | 369 | 836 | 75 | 216 | 291 | 135 | 176 | 416 |

| NIHSS score (median, IQR) | 12 (6–18) | 14 (8–19) | 12 (6–17) | 11 (6–16) | 10 (5–16) | 12 (6–19) | 12 (6–19) | 12 (5–18) | 10 (5–16) |

| Age (y) (mean and SD) | 67.6 (15.5) | 68.2 (14.4) | 64.7 (15.4) | 64.1 (16.7) | 67.4 (15.2) | 69.8 (15.2) | 67.5 (16.4) | 68.4 (16.8) | 71.6 (14.9) |

| Women (%) | 1241 (49.5%) | 178 (48.2%) | 407 (48.7%) | 38 (50.7%) | 109 (50.5%) | 141 (48.4%) | 74 (54.8%) | 93 (54.1%) | 201 (48.6%) |

| Race (black) | 480 (19.1%) | 57 (15.4%) | 243 (29.1%) | 26 (34.7%) | 76 (35.2%) | 26 (8.9%) | 20 (14.8%) | 17 (9.7%) | 15 (3.6%) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 280 (11.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 121 (14.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | 6 (2.8%) | 49 (16.8%) | 59 (43.7%) | 17 (9.7%) | 21 (5.0%) |

| NIHSS score 0–3 | 256 (10.2%) | 10 (2.7%) | 61 (7.3%) | 7 (9.3%) | 36 (16.7%) | 26 (8.9%) | 12 (8.9%) | 29 (16.5%) | 75 (18.0%) |

| NIHSS score 4–5 | 279 (11.1%) | 36 (9.8%) | 99 (11.8%) | 7 (9.3%) | 25 (11.6%) | 28 (9.6%) | 17 (12.6%) | 17 (9.7%) | 50 (12.0%) |

| NIHSS score ≥6 | 1979 (78.7%) | 323 (87.5%) | 676 (80.9%) | 61 (81.3%) | 155 (71.8%) | 237 (81.4%) | 106 (78.5%) | 130 (73.9%) | 291 (70.0%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SD, standard deviation.

Data presented as mean (SD), n (%), or median (25th, 75th percentiles). A through H represents each individual deidentified SPOTRIAS center.

Figure 1.

(A) Total number of patients treated with IV rt-PA across the SPOTRIAS network; (B) Number of patients treated with IV rt-PA with NIHSS ≤ 3.

Across the SPOTRIAS network, there was a significant difference in the proportion of stroke patients treated with IV rt-PA who had an NIHSS score of 0 to 3, 4 to 5, and ≥6 (Chi-square 14 df; P <.0001). The proportion of patients who were treated with an NIHSS score of 0 to 3 was 10.2% across the entire consortium (range 2.7–18.0%; P < .0001). The proportion treated in the NIHSS 4 to 5 category was 11.1% across the entire consortium (range 9.3–12.6%). Across the network, the proportion of patients who treated with IV rt-PA who had mild strokes (NIHSS score 0–3) increased from 4.8% in 2005 to 10.7% in 2009 (P =.001).

Discharge outcome information is available for 2391 patients (Table 2). Overall, 850 (35.6%) patients were discharged home. The proportion of patients who were discharged home when the NIHSS score was 0 to 3 was 66.8% across all the centers, although there was significant variability based on the SPOTRIAS site (range 57.1–80.0%). A substantial proportion of individuals with pretreatment NIHSS scores of 0 to 3 were discharged to an acute rehabilitation program (41/246; 16.7%). Only 5 (2%) patients with a mild stroke (NIHSS score 0–3) died, and 3 of the 5 had an intracerebral hemorrhage.

Table 2.

Outcomes patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis across the SPOTRIAS network

| NIHSS score | All | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge to home | 0–3 | 171/246 (69.5%) | 8/10 (80.0%) | 38/61 (62.3%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 27/34 (79.4%) | 18/25 (72.0%) | 8/12 (66.7%) | 16/28 (57.1%) | 51/69 (73.9%) |

| 4–5 | 159/270 (58.9%) | 19/34 (55.9%) | 60/99 (60.6%) | 6/7 (85.7%) | 17/25 (68.0%) | 15/26 (57.7%) | 15/17 (88.2%) | 9/17 (52.9%) | 18/45 (40.0%) | |

| ≥6 | 520/1875 (27.7%) 101/320 (31.6%) 194/674 (28.8%) 13/56 (23.2%) 50/154 (32.5%) 59/165 (35.8%) 28/106 (26.4%) 31/127 (24.4%) | 44/273 (16.1%) | ||||||||

| Death | 0–3 | 5/256 (2.0%) | 1/10 (10.0%) | 0/61 (0.0%) | 0/7 (0.0%) | 0/36 (0.0%) | 2/26 (7.7%) | 0/12 (0.0%) | 2/29 (6.9%) | 0/75 (0.0%) |

| 4–5 | 5/279 (1.8%) | 1/36 (2.8%) | 2/99 (2.0%) | 0/7 (0.0%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 0/28 (0.0%) | 1/17 (5.9%) | 1/17 (5.9%) | 0/50 (0.0%) | |

| ≥6 | 255/1979 (12.9%) | 49/323 (15.2%) | 85/676 (12.6%) | 9/61 (14.8%) | 8/155 (5.2%) | 19/237 (8.0%) | 13/106 (12.3%) 23/130 (17.7%) | 49/291 (16.8%) | ||

Data presented as n (%). A through H represents each individual deidentified SPOTRIAS center.

Discussion

We found a significant variability in the proportion of patients who were treated with IV rt-PA who had a mild deficit among the comprehensive stroke centers in SPOTRIAS, despite previous studies revealing thata high proportion of patients with mild stroke who are not treated with IV rt-PA have a poor neurologic outcome.9–12 There may be several explanations for the observed variability. First, the threshold for the decision to treat a mild stroke with rt-PA differs between physicians at the various centers and between centers overall. Second, the use of baseline imaging techniques was variable. Each center has different practices on using multimodality imaging (magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic [CT] scans) in the clinical evaluation for thrombolysis and included them at various time intervals, potentially leading to the identification of those patients with a large-vessel occlusion that are at higher risk for having a poor outcome.10,16 Data about the use of CT angiography at the centers was not collected as part of the SPOTRIAS database. Third, the variability in treatment may also reflect different degrees of comfort for providing a treatment with associated risk of cerebral hemorrhage versus the perceived mild nature of the deficits. Fourth, our findings may reflect different degrees of tolerance in treating possible stroke mimics versus withholding IV rt-PA. Lastly, the variability may be the result of unique patient population characteristics at each of the treating hospitals, transfer patterns, telemedicine practices, or hospital-specific protocols. For example, the threshold for contacting the stroke team may vary among emergency physicians who may call for evaluation only for patients with more severe syndromes. We also found that over the 5 years, an increasing number of patients were treated with IV rt-PA, including in the mild NIHSS categories. The latter may be a reflection of increasing awareness of the literature describing poor outcomes in those left untreated, or an effect of directly participating in SPOTRIAS.

As in previous studies, we found that a surprisingly high proportion of patients with mild syndromes were not discharged home.9–12,14,17 The explanation for the observation of poor outcomes among patients with mild stroke is not known. It may be that clinicians are treating those at risk for a poor outcome, such as those with a large arterial occlusion or a large decline in the NIHSS score9–11,16 or a high NIHSS score on isolated items related to disability (for example, isolated major weakness of arm and leg with a NIHSS score of 4), and our outcomes are driven by those patients. An NIHSS score of 2 could reflect isolated dysarthria, sensory loss, or leg paresis, each of which could portend a different disability and predicted recovery; severe aphasia in 1 patient could result in a tendency toward treatment with IV rt-PA, while only mild numbness and mild arm drift in another could result in a tendency toward non-treatment. Comparisons with the outcomes reported in other studies are difficult. We analyzed outcomes in patients treated with recanalization therapies, while the previous studies reporting poor outcomes concentrate on those who were not given IV rt-PA.9–12,14,17 In addition, not all groups have shown poor discharge outcomes in mild stroke patients not treated with thrombolysis.18 There are no randomized clinical trials specifically examining recanalization therapies in patients with mild stroke. In the NINDS t-PA trial, 58 of the 624 participants (9.3%) had a NIHSS score of ≤5, and there was no treatment by severity interaction.19 Part of the explanation of the range in outcomes reported in minor stroke patients may be the variable timing for the outcome (discharge vs 3 months) and inconsistent definitions used for minor stroke.14

This study has several limitations. This was a not prospective study that included all treated and untreated patients, and as such we are not able to answer the questions as to why some patients with mild deficits may have been treated while others were not. The itemized NIHSS was not collected, and the decision to treat patients with an NIHSS score of 0 to 3 may be different based on the nature of the neurologic deficit. The presence of a large artery occlusion or a rapid decline in the NIHSS score is not available in our database.9–11 We did not have uniform data collection protocols across sites for abstracting rates of symptomatic hemorrhage or 90-day outcomes, although several studies examining treatment of mild stroke have only examined discharge outcomes. Lastly, our data involved large academic medical centers and may not be generalizable to other networks of community hospitals.

Overall, we found wide variability in the proportion of patients with mild deficits treated across a network of academic stroke centers who have a great experience with acute stroke treatment and acute stroke trials and who work collaboratively on many ongoing stroke trials. This variability is a reflection of the uncertainty about the use of thrombolysis in these patients even at experienced centers. Variability at community hospitals or less experienced hospitals is likely to be substantially greater. Published guidelines provide few specific recommendations for these patients. The variability in practice and outcomes, even at experienced academic stroke centers, and the lack of clinical trial data for this group of patients highlight the need for a randomized trial to clarify the use of thrombolysis in patients with the mildest strokes.

Acknowledgments

Specialized Program of Translational Research in Acute Stroke (SPOTRIAS) sites are as follows: Columbia University, New York, New York (primary investigator [PI] Randolph Marshall); University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, Section on Stroke Diagnostics and Therapeutics (PI Joseph Broderick); Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland (PI Steven Warach); Department of Neurology, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri (PI Colin Derdeyn); Stroke Division, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (PI Karen Furie); Department of Neurology, University of Texas-Houston, Houston, Texas (PI James Grotta); Department of Neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California (PI Jeffrey Saver); and Department of Neurology, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California (PI Brett Meyer).

Supported in part by the Intramural Division of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/National Institutes of Health. SPOTRIAS is funded by the National Institutes of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS P50 NS049060). JZW was funded by NINDS 1K23NS073104-01A1.

References

- 1.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumacher HC, Bateman BT, Boden-Albala B, et al. Use of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 1999 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bambauer KZ, Johnston SC, Bambauer DE, et al. Reasons why few patients with acute stroke receive tissue plasminogen activator. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:661–664. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Schneider A, et al. Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke: A population-based study. Stroke. 2004;35:e27–e29. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109767.11426.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for minor strokes: The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams H, Adams R, Del Zoppo G, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: 2005 guidelines update a scientific statement from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2005;36:916–923. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000163257.66207.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams HP, Jr, Adams RJ, Brott T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: A scientific statement from the Stroke Council of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2003;34:1056–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000064841.47697.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocho D, Belvis R, Marti-Fabregas J, et al. Reasons for exclusion from thrombolytic therapy following acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2005;64:719–720. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152041.20486.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nedeltchev K, Schwegler B, Haefeli T, et al. Outcome of stroke with mild or rapidly improving symptoms. Stroke. 2007;38:2531–2535. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajajee V, Kidwell C, Starkman S, et al. Early MRI and outcomes of untreated patients with mild or improving ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2006;67:980–984. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237520.88777.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith EE, Abdullah AR, Petkovska I, et al. Poor outcomes in patients who do not receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator because of mild or improving ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2497–2499. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185798.78817.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, et al. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology. 2001;56:1015–1020. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bath PM, Martin RH, Palesch Y, et al. Effect of telmisartan on functional outcome, recurrence, and blood pressure in patients with acute mild ischemic stroke: A PRoFESS subgroup analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:3541–3546. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.555623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer U, Baumgartner A, Arnold M, et al. What is a minor stroke? Stroke. 2010;41:661–666. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.572883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards DF, Hahn M, Baum C, et al. The impact of mild stroke on meaningful activity and life satisfaction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;15:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coutts SB, O’Reilly C, Hill MD, et al. Computed tomography and computed tomography angiography findings predict functional impairment in patients with minor stroke and transient ischaemic attack. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hills NK, Johnston SC. Why are eligible thrombolysis candidates left untreated? Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6 Suppl 2):S210–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Berg JS, de Jong G. Why ischemic stroke patients do not receive thrombolytic treatment: Results from a general hospital. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;120:157–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khatri P, Kleindorfer DO, Yeatts SD, et al. Strokes with minor symptoms: An exploratory analysis of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke recombinant tissue plasminogen activator trials. Stroke. 2010;41:2581–2586. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]