Abstract

Background and Purpose

Erythropoietin (EPO) confers potent neuroprotection against ischemic injury. However, treatment for stroke requires high doses and multiple administrations of EPO, which may cause deleterious side effects due to its erythropoietic activity. This study identifies a novel non-erythropoietic mutant EPO (MEPO) and investigates its potential neuroprotective effects and underlying mechanism in animal model of cerebral ischemia.

Methods

We constructed a series of MEPOs, each containing a single amino acid mutation within the erythropoietic motif, and tested their erythropoietic activity. Using cortical neuronal cultures exposed to NMDA neurotoxicity and a murine model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), neuroprotection and neurofunctional outcomes were assessed as well as activation of intracellular signaling pathways.

Results

The serine to isoleucine mutation at position 104 (S104I-EPO) completely abolished the erythropoietic and platelet-stimulating activity of EPO. Administration of S104I-EPO significantly inhibited NMDA-induced neuronal death in primary cultures, and protected against cerebral infarction and neurological deficits with an efficacy similar to that of wild-type EPO. Both S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO activated similar pro-survival signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK1/2 and STAT5. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT or MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling pathways significantly attenuated the neuroprotective effects of S104I-EPO, indicating that activation of these pathways underlies the neuroprotective mechanism of MEPO against cerebral ischemia.

Conclusions

S104I-EPO confers neuroprotective effects comparable to those of wild-type EPO against ischemic brain injury, with the added benefit of lacking erythropoietic and platelet-stimulating side effects. Our novel findings suggest that the non-erythropoietic mutant EPO is a legitimate candidate for ischemic stroke intervention.

Keywords: erythropoietin, erythropoietin mutant, cerebral ischemia, neuroprotection, neurotoxicity, AKT, ERK1/2

Introduction

EPO is a potent neuroprotectant against ischemic brain injury both in animal experiments1,2 and in the clinic3. Thus, using EPO as a neuroprotective approach in stroke, especially in treatment of patients who are not suitable for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment, represents a potentially exciting new clinical application. However, large doses and multiple administrations of EPO are required for the treatment of stroke. Such a regimen of EPO administration may result in multiple high risk factors for stroke patients due to the erythropoietic effects of EPO, such as increases in hematocrit, quantity of platelets and vascular muscle contraction, raising the likelihood of microcoagulation and secondary infarction. EPO may also potentially interact with or be contraindicated with thrombolytic drugs and cause unexpected side effects, as evidenced by a recently failed EPO/tPA combinatorial clinical trial4. Accordingly, alternate strategies to reduce erythropoietic activity and other potential side effects of EPO will greatly improve its clinical applicability for the treatment of stroke.

A recent study indicated that a MEPO lacking erythropoietic activity was neuroprotective against NMDA toxicity in cultured neurons5. However, the in vitro model bypasses all the vascular events critical in stroke pathology. Thus, whether MEPO has neuroprotective effects against brain ischemia still remains unknown. In this study, we constructed and subsequently tested a series of MEPOs, each containing a single amino acid mutation within the erythropoietic motif, and characterized a MEPO which completely lacked erythropoietic activity, but retained neuroprotective effects against in vitro neural excitotoxicity. We then further investigated this MEPO in the context of in vivo cerebral ischemia, and explored the potential signaling mechanisms underlying the observed neuroprotection.

Materials and methods

Generation of MEPO protein

His6-tagged (3’end) EPO cDNAs, each containing a single amino acid mutation, were generated by PCR-based site mutagenesis and transfected into 293 cells. Recombinant protein was purified from the culture medium of 293 stable cell lines overexpressing MEPO using superflow Ni-NTA agarose columns (Qiagen).

Bioactivity assays of MEPO

In vitro bioactivity was determined using a proliferation assay in the EPO-dependent murine myeloid cell line 32D-EPOR. 32D-EPOR cells (2×105 cells/well) were factor-starved for 4 h in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen), and then incubated in the presence of MEPOs or wild-type EPO (1 U/ml). Live cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion 72 h later. For in vivo erythropoietic activity bioassay, C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were intraperitoneally injected with S104I-EPO or wild-type EPO twice weekly for four weeks at a dose of 5000 U/kg BW. Hemoglobin and platelet levels were determined before the first EPO administration, and then analyzed every 2 weeks.

NMDA neurotoxicity

Primary cortical neurons at 11 DIV from pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were pretreated with MEPOs or wild-type EPO (1 U/ml) for 8 h, and then challenged with N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA, 200 µM) for 15 min. The neurons were then returned to normal culture medium supplied with the same concentration of MEPOs or wild-type EPO. Cell death was analyzed by nuclear staining (Hoechst 33258) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release 24 h after NMDA treatment.

Murine model of focal ischemia, drug administration and determination of infarct volume

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Temporary focal ischemia was induced by left middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) for 60 min as previously described6. Animals were randomized and S104I-EPO, wild-type EPO or vehicle (saline) was administered intraperitoneally at the concentration indicated at the onset of reperfusion, and again at 24 and 48 h of reperfusion. Pharmacological inhibitors of PI3K (2 µl of 10 mM LY294002) and ERK (2 µl of 5 mM PD98059) were injected (intracerebroventricularly) individually or in combination into the brain 30 min prior to MCAO. Infarct volume was determined 72 h after MCAO by a researcher blinded to the experimental groups using the MCID image analysis system (Imaging Research, Inc.) after 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining.

Neurobehavioral tests

Three different neurobehavioral tests were performed in animals by an observer blinded to the experiments. Neurological deficits were scored on a 0 to 5 scale: no neurological deficit (0); failure to extend the right forepaw fully (1); circling to the right (2); falling to the right (3); unable to walk spontaneously (4); dead (5). The Rotarod test was begun 2 days before surgery and then administered on a daily basis at 1 to 7 days after surgery, with 5 trials per test. For the corner test, the ischemic mouse turns preferentially toward the non-impaired (right) side. The turns in one versus the other direction are recorded from ten trials for each test. The data are expressed as the percentage of mean duration of time on the Rotarod per day compared with the presurgery control value.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean±SEM. The statistical significance of the difference between means was analyzed by the Student’s t test for single comparisons or by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn tests for multiple comparisons. Differences among groups were regarded as significant if p≤0.05.

Results

Generation of neuroprotective MEPOs that lack erythropoietic activity

To obtain MEPOs that lack erythropoietic activity, we constructed and subsequently tested 12 EPO mutants, each containing a single amino acid mutation within three EPOR-binding motif regions that are essential for EPO’s erythropoietic activity7, 8: the amino terminal (amino acids 1–17), internal (amino acids 99–109) and carboxyl-terminal motif (amino acids 147–151). The bioactivity of these MEPOs was analyzed using an in vitro proliferation assay in the EPO-dependent myeloid cell line 32D-EPOR. As shown in Fig. 1A, the survival and proliferation of 32D-EPOR cells depends entirely on the existence of EPO in the medium. Mutations within the carboxyl-terminal motif (N147A, N147K and G151A) either increased or only partially reduced EPO bioactivity, while mutations within the amino-terminal motif (R14E, R14A, R14Q and Y15I) significantly reduced but did not completely abolish EPO bioactivity. However, mutations within the internal motif (S100E, R103A, R103E, S104I and L108K) resulted in complete loss of EPO bioactivity (Fig. 1A), consistent with previous reports, indicating that the internal motif is essential for EPO bioactivity7, 8.

Figure 1. Screening of MEPOs that lack erythropoietic activity.

A, Live cell counts by trypan blue exclusion 72 h after treatment of MEPOs in 32D-EPOR cells. B, Quantitative analysis of cell death by Hoechst staining 24 h after NMDA challenge in the presence of MEPOs in primary neurons. Medium and wild-type EPO were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Data are presented as mean±SEM from three independent experiments.

Next, we tested whether the MEPOs retain neuroprotective effects against excitotoxic neural injury. MEPOs significantly reduced NMDA-induced neuronal cell death, with an efficacy similar to that of wild-type EPO (Fig. 1B). However, there was a non-significant trend toward better protection against NMDA toxicity following mutations within the internal motif compared to mutations within the amino terminal. Taken together, the above data suggest that, although all amino terminal or internal motif MEPOs assayed retained equivalent neuroprotection against NMDA neurotoxicity compared to wild-type EPO, mutations within the amino terminal motif resulted in only a partial loss of EPO bioactivity. In contrast, mutations within the internal motif not only retained neuroprotective effects, but also caused a complete loss of EPO bioactivity. We therefore chose mutants with mutations within the internal motif for further assessment.

Characterization of S104I-EPO

Amino acid residues 100, 103, 104 and 108 are exposed on the surface of the EPO molecule; thus, change of charge may potentially result in EPO binding to new targets due to charge-charge interactions. Among the five mutants targeting the internal motif, only S104I-EPO is a neutral amino acid substitution, while the other mutations either increased or decreased the charge. Interestingly, the 293 cells secreted higher levels of S104I-EPO into the medium compared to other MEPOs. The mechanism for this remains unclear, but it is likely due to impaired EPO secretion mechanism caused by charge change. Based on these observations, we chose S104I-EPO for further investigation.

S104I-EPO completely lost the ability to induce myeloid proliferation, even at a high concentration (100 U/ml, equivalent to 25 nM, Fig. 2A). To further confirm whether S104I-EPO loses its erythropoietic activity, hemoglobin levels in mice were measured following injection of a high dose of either S104I-EPO or wild-type EPO (both at 5000 U/kg) twice weekly. As shown in Fig. 2B, S104I-EPO did not induce the production of hemoglobin even when continuously present at high concentrations over 4 weeks, whereas wild-type EPO significantly increased hemoglobin level at weeks 2 and 4 (by 15% and 39%, respectively). EPO has been reported to stimulate the production of platelets, which may increase the likelihood of microcoagulation and secondary stroke, we therefore also measured platelet levels in mice. S104I-EPO administration did not induce the production of platelets at least up to 4 weeks post-treatment, while wild-type EPO significantly increased the platelet counts (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. S104I-EPO completely loses erythropoietic activity, but is neuroprotective.

A, In vitro bioactivity assay of S104I-EPO as assessed by live cell counting using trypan blue exclusion in the 32D-EPOR cells. Data are mean±SEM from three independent experiments. B and C, In vivo erythropoietic and platelet-stimulating activity assay by measuring hemoglobin and platelet levels. Data are presented as mean±SEM, n=8 per group. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01 versus wild-type EPO injection group. D, Phase contrast (a–d) and Hoechst staining (e–h) of primary neurons challenged with NMDA. NMDA induces both apoptotic-like (red arrows) and necrotic-like cell death (yellow arrows). Pre-treatment with either EPO (c, g) or S104I-EPO (d, h) reduced both types of neuronal death. i, Quantitative counting of cell death induced by NMDA neurotoxicity. j, Relative LDH release compared with NMDA treatment alone. #P≤0.05 versus NMDA alone. Data are mean±SEM from three independent experiments.

To determine whether S104I-EPO retains neuroprotective effects, we first tested it in an in vitro model of NMDA neurotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures. As illustrated, pretreatment with S104I-EPO significantly decreased the number of neurons containing condensed nuclei in cultures (Fig. 2D–g, 2D–h, 2D–i), and prevented necrotic cell death following NMDA treatment as determined by LDH release (Fig. 2D–j). Importantly, no significant difference in neuroprotective efficacy was observed between S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO, suggesting that S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO are equally effective in protecting neurons against NMDA neurotoxicity with a mixed cell death phenotype.

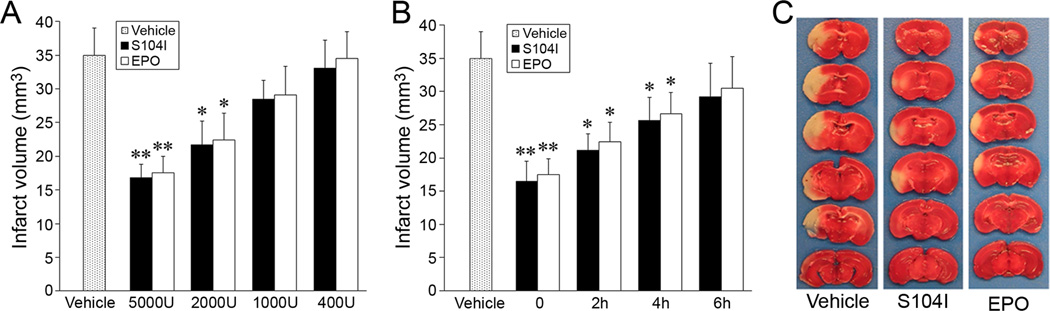

S104I-EPO is neuroprotective against focal cerebral ischemia

The neuroprotective effects of S104I-EPO were further determined in the murine model of focal ischemia. S104I-EPO treatment significantly decreased infarct volume in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, B), with an efficacy similar to that of the wild-type EPO. S104I-EPO provided optimal protection at a concentration of 5000 U/kg administered intraperitoneally, a dose that has been widely used in the field to test the neuroprotective effect of wild-type EPO in rodent models of cerebral ischemia5, 9. At this dose, S104I-EPO reduced infarct volume by 53% (Fig. 3A, C). S104I-EPO still exerted significant neuroprotection at 2000 U/kg, but the effect disappeared when administered at doses under 1000 U/kg.

Figure 3. S104I-EPO reduces infarct volume.

A, Dose efficacy of S104I-EPO on reduction of infarct volume. B, Temporal profile of S104I-EPO (5000 U/kg) on reduction of infarct volume. C, Representative photographs of TTC-stained sections of mouse brains. The same dose of wild-type EPO was used as control in all groups. All quantitative data are mean±SEM, n=8 per group. *P≤0.05 versus vehicle group, **P≤0.01 versus vehicle group.

In order to determine the temporal time frame for neuroprotection, we examined whether post-ischemic administration of S104I-EPO would be capable of decreasing ischemic infarct volume. Injection of S104I-EPO immediately following the ischemic period provided optimal protection. However, S104I-EPO exerted significant neuroprotective effects even when administered up to 4 h after ischemia, although the effects were diminished and lost when administered 6 h following ischemia. Physiological parameters (blood pressure, gases and glucose) and rCBF were measured with no significant differences between groups (data not shown).

Administration of S104I-EPO improves neurological outcomes after ischemia

We next tested whether the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO could be translated into functional improvement. S104I-EPO significantly improved neurological deficit scores as assessed at 72 h following ischemia (Fig. 4A). To further determine the impact of S104I-EPO on neurological recovery, two behavioral tests, the Rotarod and corner tests, were performed during a 7-day recovery period. As illustrated in Fig. 4B, S104I-EPO-treated mice performed significantly better on the Rotarod at all time points tested following ischemia compared with vehicle-treated mice. Similarly, S104I-EPO-treated mice decreased preferential turning behavior toward the non-impaired (right) side as assessed by the corner test, indicating improved bilateral motor behavior compared to vehicle-treated mice. No significant differences were found for functional outcomes between S104I-EPO-treated and wild-type EPO-treated mice, suggesting that S104I-EPO improves neurological outcomes with an efficacy similar to that of wild-type EPO.

Figure 4. S104I-EPO treatment improves neurological outcomes.

S104I-EPO treatment improves neurological outcomes as determined by neurological deficit scores (A), Rotarod test (B), and corner test (C). * P≤0.5 versus vehicle group.

S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO exert neuroprotective effects via similar signaling pathways

We next sought to determine if MEPO and wild-type EPO activate similar cell survival pathways. Previous studies suggested that EPO derivatives do not bind to EPO receptors, but rather to a tissue-protective receptor complex, the Common β receptor/EPOR heteroreceptors10. However, the downstream survival signaling pathways relevant to ischemic neuroprotection may be similar to those activated by wild-type EPO. Therefore, we tested whether MEPO mediates neuroprotection via PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK1/2 and STAT5 signaling, as these pathways are critical to the neuroprotective effects of EPO2,11. Primary neurons were treated with S104I-EPO, and the activation of signaling molecules was analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 5A). Similar to wild-type EPO, S104I-EPO increased the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 as early as 30 min after exposure. Increased phospho-AKT and phospho-ERK1/2 levels were observed over the time course assessed, including 24 h following exposure. S104I-EPO also increased the level of phosphorylated STAT5, beginning 16 h after S104I-EPO exposure. To determine the role of these signaling pathways in the context of MEPO-mediated neuroprotection, primary neurons were challenged with NMDA in the presence or absence of either the PI3K inhibitor LY294022 (Fig. 5B) or the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (Fig. 5C). Both inhibitors significantly decreased the protective effects of EPO and S104I-EPO against NMDA neurotoxicity. Finally, we tested the relevance of these signaling pathways in MEPO-mediated neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia in mice. ICV injection of either LY294002 or PD98059 led to a diminished neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO, and combined injection of LY294002 and PD98059 completely abolished S104I-EPO-induced neuroprotection. Injection of LY294002 or PD98059 alone did not show a significant difference compared to the vehicle control group. These data suggest that the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways may synergistically mediate the neuroprotective effect of MEPO. Furthermore, the data underscore that both S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO may activate similar signaling pathways to induce neuroprotection.

Figure 5. S104I-EPO activates the same survival signaling pathways as wild-type EPO.

A, S104I-EPO activates the phosphorylation of AKT, ERK1/2 and STAT5 in primary neuronal cultures. AKT inhibitor LY294002 (LY, B) and ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (PD, C) attenuated the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO against NMDA neurotoxicity as assessed by Hoechst staining of nuclei. The same dose of wild-type EPO was used as control in all groups. D, Effect of AKT and ERK1/2 inhibitors on infarct volume in S104I-EPO-treated groups. Data are mean±SEM, *P≤0.05 versus S104I-EPO-treated groups.

Discussion

EPO exerts a potent neuroprotective effect against ischemic brain injury in both animal experiments and clinical trials3,12. However, several critical limitations have hampered the potential for extensive use of EPO as a clinically therapeutic tool following stroke. Of primary concern, the delivery of EPO to the brain via systemic administration is technically challenging. EPO does not easily cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and possesses a relatively low affinity for receptors involved in tissue protection compared to receptors for erythropoietic function. The delivery of EPO to the brain can be enhanced by addition of protein transduction peptide6, but this still requires doses higher than that used for the treatment of kidney anemia. Second, the activation of signaling pathways diminishes 24–48 h following EPO exposure (unpublished observations), raising the possibility that multiple administrations of EPO may be required for treatment of stroke and rekindling of signaling pathways over the course of the injury. Multiple administrations of high doses of EPO may result in increased risk factors for stroke patients, such as increased hematocrit and platelet quantity, which could give rise to secondary infarction. Accordingly, alternate strategies to develop non-erythropoietic EPO derivatives will greatly improve the potential for clinical application in the treatment of stroke patients.

Three types of EPO derivatives have been generated that lack erythropoietic activity yet retain neuroprotective effects: asialoerythropoietin13, carbamylated EPO5 and MEPO5. Of all these options, MEPO possesses the optimal translatable potential as a therapy. For example, the plasma half-life of intravenously injected asialoerythropoietin is only 1.4 minutes due to rapid clearance. Thus, continuous administration of asialoerythropoietin is likely needed in order to compensate for clearance prior to crossing the BBB14. Although a single injection of asialoerythropoietin has been shown to be neuroprotective against ischemic brain injury13, the timing of this injection may require precise correlation with BBB compromise, a situation with limited clinical applicability. Carbamylated EPO, in which all eight lysine residues are chemically modified to homocitrulline, has also been demonstrated to exert ischemic neuroprotection. However, MEPO has several major advantages over carbamylated EPO in potential clinical applicability. First, the generation and purification of MEPO is fairly straightforward and does not require the complex chemical modifications necessary for carbamylated EPO. The option of MEPO thus significantly reduces the production/cost value compared to carbamylated EPO. Second, MEPO contains a single amino acid substitution. The conversion of all eight lysine residues to homocitrulline to generate carbamylated EPO leads to extensive modification of amino acid residues, and thus has a higher probability of incurring structural and functional alterations. Consistent with this, carbamylated EPO loses angiogenic function15, whereas S104I-EPO retains both angiogenesis and neurogenesis effects (unpublished data). The retention of these effects by S104I-EPO indicates that potentially critical structural elements of EPO are maintained in S104I-EPO.

We found that mutations within the internal motif region of EPO result in complete loss of erythropoietic activity, while mutations within the amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal motifs only partially attenuated erythropoietic activity. These data support previous reports that the internal motif is crucial for binding to EPOR and erythropoiesis7,8. The complete lack of erythropoietic and platelet-stimulating activity bodes well for reducing complications in the ischemic setting. Indeed, we found no deleterious side effects in physiological parameters or ischemic outcomes under our treatment paradigm. Importantly, the current study also demonstrates that S104I-EPO not only inhibits NMDA-induced neuronal death in primary cultures (Fig. 2D), but also reduces infarct volume and improves postischemic neurological outcomes in a murine MCAO model (Fig. 4). Our results indicate that such a non-erythropoietic EPO mutant may be a promising candidate for treatment of brain injury, and may avoid clinical complications associated with increased hematocrit or platelet aggregation. Obviously, before moving to clinical trials, further investigations are required, such as whether MEPO has long-term blood-stimulating and other undiscovered side effects, and whether MEPO administration has long-term effects on histological and behavioral improvements after ischemia. In addition, the effect of MEPO needs to be tested in multiple ischemic model/species systems according to STAIR guidelines. Considering that side effects of EPO in stroke therapy may not appear in animal stroke models, testing MEPO in non-human primates may also be necessary before clinical trials.

The precise mechanism underlying the neuroprotective effect of MEPO remains unknown. A previous study indicated that EPO derivatives incapable of binding to classical EPO homoreceptors may mediate neuroprotection via binding to a tissue protective receptor consisting of both the common β receptor and the EPOR, forming a heteroreceptor that activates similar survival signaling pathways activated by wild-type EPO, such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK1/210. Consistent with this concept, we found that both S104I-EPO and wild-type EPO activate the same signaling pathways in neurons, such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK1/2 and STAT5 (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of these signaling pathways using either the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 not only attenuated the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO against NMDA-induced neurotoxicity (Fig. 5B–C), but also inhibited the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO against ischemic brain injury in the MCAO model (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, combined application of LY294002 and PD98059 completely abolished the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO in ischemia, suggesting that PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways may synergistically mediate the neuroprotective effect of S104I-EPO. The observation that STAT5 activation is delayed until 16 h after addition of S104I-EPO suggests that STAT5 signaling might occur downstream of either PI3K/AKT or MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling. The further characterization of neuroprotective signaling triggered by MEPO warrants additional investigation, including the identification of the receptor required for neuroprotection, a deeper understanding of downstream signaling molecules and the exploration of parallel signaling pathways.

In summary, S104I-EPO completely lacks erythropoietic activity, but retains neuroprotective effects against in vitro NMDA neurotoxicity and ischemic brain injury in a murine model of MCAO, with an efficacy similar to that of wild-type EPO. Furthermore, although S104I-EPO activates survival signaling pathways similar to those of wild-type EPO, the non-erythropoietic feature of S104I-EPO avoids important clinical confounds for the stroke patient. Thus, the novel S104I-EPO should be explored as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of stroke and other neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rehana K. Leak and Carol Culver for editorial assistance and Professor Murat O. Arcasoy from Duke University for providing the 32D-EPOR cell line.

Sources of Funding

This project was supported by VA Merit Review grant 1I01RX000199 (to G.C.), National Institutes of Health/NINDS grant NS053473 (to G.C.), and AHA Scientist Development Grant 06300064N (to G.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Sakanaka M, Wen TC, Matsuda S, Masuda S, Morishita E, Nagao M, et al. In vivo evidence that erythropoietin protects neurons from ischemic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4635–4640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Signore AP, Zhou Z, Wang S, Cao G, Chen J. Erythropoietin protects ca1 neurons against global cerebral ischemia in rat: Potential signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Dembowski C, Cepek L, Lewczuk P, Stiefel M, et al. Erythropoietin therapy for acute stroke is both safe and beneficial. Mol Med. 2002;8:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenreich H, Weissenborn K, Prange H, Schneider D, Weimar C, Wartenberg K, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:e647–e656. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leist M, Ghezzi P, Grasso G, Bianchi R, Villa P, Fratelli M, et al. Derivatives of erythropoietin that are tissue protective but not erythropoietic. Science. 2004;305:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1098313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, Xing J, Liou AK, Wang S, Gan Y, Luo Y, et al. Enhanced delivery of erythropoietin across the blood-brain barrier for neuroprotection against ischemic neuronal injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2010;1:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott S, Lorenzini T, Chang D, Barzilay J, Delorme E. Mapping of the active site of recombinant human erythropoietin. Blood. 1997;89:493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen D, Boissel JP, Showers M, Ruch BC, Bunn HF. Erythropoietin structure-function relationships. Identification of functionally important domains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22839–22846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brines ML, Ghezzi P, Keenan S, Agnello D, de Lanerolle NC, Cerami C, et al. Erythropoietin crosses the blood-brain barrier to protect against experimental brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10526–10531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brines M, Grasso G, Fiordaliso F, Sfacteria A, Ghezzi P, Fratelli M, et al. Erythropoietin mediates tissue protection through an erythropoietin and common beta-subunit heteroreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14907–14912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406491101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilic E, Kilic U, Soliz J, Bassetti CL, Gassmann M, Hermann DM. Brain-derived erythropoietin protects from focal cerebral ischemia by dual activation of erk-1/-2 and akt pathways. Faseb J. 2005;19:2026–2028. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3941fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrenreich H, Kastner A, Weissenborn K, Streeter J, Sperling S, Wang KK, et al. Circulating damage marker profiles support a neuroprotective effect of erythropoietin in ischemic stroke patients. Mol Med. 2011;17:1306–1310. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbayraktar S, Grasso G, Sfacteria A, Xie QW, Coleman T, Kreilgaard M, et al. Asialoerythropoietin is a nonerythropoietic cytokine with broad neuroprotective activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6741–6746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031753100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price CD, Yang Z, Karlnoski R, Kumar D, Chaparro R, Camporesi EM. Effect of continuous infusion of asialoerythropoietin on short-term changes in infarct volume, penumbra apoptosis and behaviour following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez R, Carracedo J, Nogueras S, Buendia P, Merino A, Canadillas S, et al. Carbamylated darbepoetin derivative prevents endothelial progenitor cell damage with no effect on angiogenesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]