Abstract

Background

It is not known if endothelial dysfunction, an important early event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, is present in mild primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) and if so, whether it improves following parathyroidectomy.

Design

We measured flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD), which estimates endothelial function by ultrasound imaging, in patients prior to and 6 and 12 months after parathyroidectomy.

Results

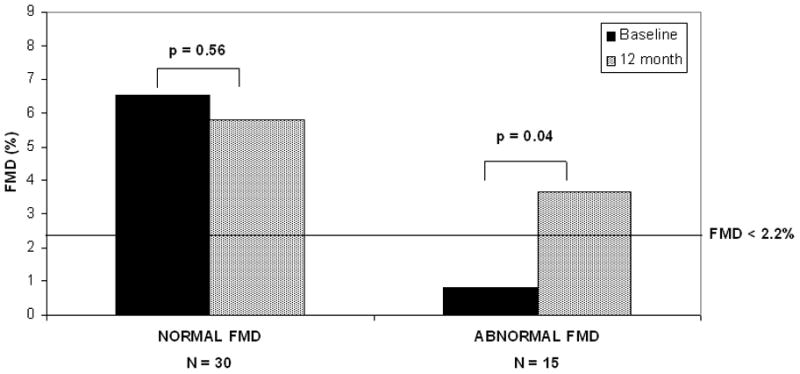

Forty-five patients with mild PHPT [80% female, 61 ± 1 (mean ± SE) years, serum calcium 2.65 ± 0.03 mmoL/L (10.6 ± 0.1 mg/dL), PTH 10.5 ± 0.7 pmol/L (99 ± 7 pg/mL), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) 70.3 ± 3.7 nmol/L (28.2 ± 1.5 ng/mL)] were studied. Baseline FMD was normal (4.63 ± 0.51%; reference mean: 4.4 ± 0.1%), and was not associated with serum calcium, PTH, or 25OHD levels. In the group as a whole, FMD did not change after surgery (6 mo: 4.38 ± 0.83%, p=0.72; 12 mo: 5.07±0.74%, p=0.49). However, in those with abnormal baseline FMD (<2.2%; N=15), FMD increased by 350%, normalizing by 6 months after surgery (baseline: 0.81 ± 0.19%; 6 mo: 3.18 ± 0.79%, p = 0.02 versus baseline; 12 mo: 3.68± 1.22%, p = 0.04 versus baseline). Baseline calcium, PTH, and 25OHD levels did not differ between those with abnormal versus normal FMD, nor did these indices predict postoperative change in FMD.

Conclusions

FMD is generally normal in patients with mild PHPT and is unchanged one year after parathyroidectomy. Although FMD may normalize after surgery in patients with baseline abnormalities, data do not support using endothelial dysfunction as an indicator for parathyroidectomy.

Keywords: Primary hyperparathyroidism, flow-mediated vasodilation, endothelial function, parathyroidectomy, hypercalcemia

Introduction

Classical primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) was associated with marked hypercalcemia, overt skeletal disease and nephrolithiasis as well as increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Over the past few decades, primary hyperparathyroidism has evolved into a less symptomatic disease and the majority of patients with PHPT today lack the classic skeletal and renal complications that characterized the disorder in the past.

While the skeletal and renal manifestations of PHPT have unmistakably evolved, it is unclear whether cardiovascular disease remains a part of the modern presentation of PHPT. Much of the data regarding the cardiovascular complications of PHPT are conflicting, which may in part reflect variation in the severity of disease studied.(1–4) For example, cardiovascular mortality is increased in PHPT patients with moderate to severe hypercalcemia, but some studies involving patients with milder hypercalcemia have not clearly shown such an increase.

As the clinical phenotype of PHPT has changed into a disorder characterized by subtler biochemical and skeletal manifestations, attention has shifted toward evaluation of subclinical cardiovascular disease, such as endothelial dysfunction. The endothelium forms the inner lining of blood vessels and has a number of crucial functions including regulating vascular tone, coagulation and inflammation. Endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide, which mediates vasodilation and inhibits platelet aggregation, as well as inflammation and thrombosis. These effects play a critical role in inhibiting the atherosclerotic process and endothelial dysfunction is thought to be an important early event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

Flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD), a noninvasive method of estimating primarily nitric-oxide dependent endothelial function, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events in subjects without known cardiovascular disease (5) and is associated with the presence of coronary artery disease.(6) Data regarding endothelial function in PHPT are conflicting and data on patients with mild disease are sparse. (7–9) Because many patients with mild PHPT are monitored without surgery for many years, it is important to understand the impact of mild PHPT on cardiovascular health, particularly in those with measurable abnormalities. We have previously reported that patients with mild PHPT have evidence of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis, but no increase in left ventricular mass or diastolic dysfunction.(10, 11) We now report on flow-mediated vasodilation in the same group of patients with mild PHPT before and after parathyroidectomy, and on the association of FMD with serum concentrations of calcium, PTH and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD).

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Design

We report on the 45 subjects from our original PHPT cohort who had parathyroidectomy and FMD measurements. As previously reported(10, 11) patients were referred from the Metabolic Bone Diseases Unit at Columbia University Medical Center between 2005 and 2008. They were between the ages of 45 – 75 years and had mild hypercalcemia [serum calcium < 3 mmol/L (12.0 mg/dL)]. xclusion criteria included bisphosphonate use within the past 2 months and the start or change in cholesterol-lowering medications within two years of study entry. Of the 46 subjects who had parathyroidectomy, 1 subject was excluded from this analysis, as she had a prior mastectomy and could not have FMD measured. Four additional subjects were excluded from the longitudinal analysis: 1 subject was lost to follow-up, 1 subject id not have follow up FMD measurements post-surgery, and 2 had persistent primary hyperparathyroidism. Subjects were interviewed to ascertain cardiovascular risk factors. Laboratory measurements and FMD were measured at baseline and then at both 6 months and 12 months post-parathyroidectomy. This study was approved by theInstitutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center. All patients gave written informed consent.

Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Hypercholesterolemia was defined as use of a lipid lowering medication or patient self-report of hyperlipidemia. Hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg, use of anti-hypertensive medications, or patient self-report of hypertension. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose level ≥ 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dl), use of insulin or hypoglycemic medications, or patient self-report of diabetes. Cigarette smoking was characterized as ever-smoked, current smoker, or never smoked. History of myocardial infarction was based on patient self-report of prior event. In addition, subjects’ medication regimens, including cholesterol and anti-hypertensive medications, were assessed at each visit.

Laboratory Measurements

Serum total calcium was measured by standard autoanalyzer techniques (Technicon Instruments, Tarrytown, NY; normal range: 2.18 – 2.55 mmol/L). Serum total calcium levels were corrected for albumin (formula: corrected calcium = total calcium + 0.8[4-albumin]). 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels [25OHD < 50 nmol/L (20 ng/mL): deficient; > 75 nmol/L (30 ng/mL): sufficient] were measured by liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry assay (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) and intact parathyroid hormone by immunoradiometric assay [Scantibodies, Santee, CA; normal range: 1.5–7.0 pmol/L (14–66 pg/mL)]. In addition, fasting glucose was measured by standard autoanalyzer technique, and insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay [Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA; reference range ≤ 210.9 pmol/L (29.4 μIU/mL)]. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP < 1.0 mg/L: low cardiovascular disease risk; 1.0 to 3.0 mg/L: average cardiovascular disease risk; > 3.0 mg/L: high cardiovascular disease risk)was measured using a particle enhanced turbidimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN; reference range < 5.0 mg/L). Total cholesterol was measured using standard autoanalyzer technique (reference range < 5.18 mmol/L).

Flow-Mediated Vasodilation Measurement

FMD measurement was performed by the following standardized method by a single technician, blinded to each subjects’ timepoint. Subjects fasted for 12 hours and avoided exercise for 4–6 hours prior to FMD measurement. The baseline diameter of the brachial artery was measured 6 centimeters above the antecubital fossa using a 7–15MHz linear array transducer (Philips 5500, Andover, MA). A standard blood pressure cuff was placed on the forearm distal to the antecubital fossa. The cuff was inflated above systolic blood pressure for five minutes then released to induce reactive hyperemia. A repeat measurement of brachial artery diameter was obtained one minute after cuff deflation. FMD was calculated using the formula: FMD(%)= 100 × [(brachial artery diameter at peak hyperemia-diameter at rest)/diameter at rest]. This procedure was repeated three consecutive times and the FMD results averaged. Intra-observer variability for FMD measurements in our laboratory is 1.3%.(12) Because there is significant variability in FMD in published studies, often due to varying measurement techniques (13), we compared our results to those obtained in a study that used the same FMD procedure, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).(5, 14) MESA, a multi-center study in which we were one of 6 participating centers, is a prospective cohort study that includes 6814 men and women between the ages of 45 to 84 years old, without known cardiovascular disease (mean FMD for random sample of MESA participants: 4.4 ± 0.1%; abnormal FMD: lowest quartile <2.2%).(5, 14)

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic data and cardiovascular risk factors are described by number, percentages and mean value ± SE as appropriate. Between-group differences in FMD were assessed with Student's T-test and for categorical variables with Chi-square or Fisher's Exact test. Change in FMD over time was assessed with linear mixed models for repeated measures. All models included fixed effect for time, group, and group by time interaction. The covariance structure of the within-subject correlation between measurement times of FMD was assessed with Auto-regressive(1). A compound symmetry structure was used for serum 25OHD. Pearson correlations were used to assess the association between continuous variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We studied 45 patients with mild PHPT (80% female, age 61 ± 1 years, serum calcium 2.65 ± 0.03 mmoL/L (10.6 ± 0.1 mg/dL), PTH 10.5 ± 0.7 pmol/L (99 ± 7 pg/mL; see Tables 1 & 2). Subjects had relatively few cardiovascular risk factors.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Data and Cardiovascular Risk Factors for 45 Subjects with PHPT (data shown as mean ± SE or percentages).

| Age (yrs) | 61 ± 1 |

| Female | 80% |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 0.6 |

| Current Smoker | 5% |

| Ever Smoked | 58% |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 36% |

| Diabetes | 2% |

| Hypertension | 33% |

| History of Myocardial Infarction | 2% |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.2 ± 0.1 (94 ± 2 mg/dL) |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 56.7 ± 8.6 (7.9 ± 1.2 μIU/mL) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.1 (209 ± 5 mg/dL) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

Table 2.

Change in Biochemistries and Endothelial Function (n = 45).

| Baseline Mean ± SE |

6 month Mean ± SE |

12 month Mean ± SE |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.65 ± 0.03 | 2.33 ± 0.03a | 2.33 ± 0.03a |

| Serum PTH (pmol/L) | 10.5 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 0.3a | 3.6 ± 0.2a |

| Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | 70 ± 4 | 92 ± 5a | 95 ± 5a |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 123 ± 2 | 121 ± 3 | 123 ± 3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74 ± 1 | 74 ± 2 | 77 ± 1b |

| Baseline brachial artery diameter (mm) | 3.40 ± 0.10 | 3.43±0.10 | 3.43 ± 0.11 |

| Brachial artery diameter post-hyperemia (mm) | 3.55 ± 0.09 | 3.57±0.10 | 3.59 ± 0.10 |

| Flow-mediated vasodilation (%) | 4.63 ± 0.51 | 4.38±0.83 | 5.07 ± 0.74 |

p-values for difference from baseline to either 6 or 12 month time-point:

p<0.0001;

p=0.007

At baseline, FMD was normal (4.63±0.51 %; MESA mean 4.4±0.1%; 25th–75th percentile: 2.2–5.9%), and was not associated with serum calcium (r=0.18, p=0.24), PTH (r=−0.06, p=0.67), or 25OHD (r=−0.19, p=0.21) levels. Mean baseline 25OHD level was in the “insufficient” range. Although only 6 patients were frankly vitamin D deficient (25OHD < 50 nmol/L), their FMD tended to be higher than FMD in those who were clearly vitamin D replete (25OHD< 50 nmol/L: 7.77 ± 1.40% vs. 25OHD>75 nmol/L, N=17: 4.60 ± 0.80%, p=0.06).

Following parathyroidectomy (Table 2), serum calcium and PTH levels normalized, as expected. Mean 25OHD levels increased. There were also small but significant increases in diastolic blood pressure (within the normal range) and body mass index [baseline BMI 25.3 ± 0.6 kg/m2, 12 month BMI: 25.9 ± 0.6 kg/m2; p = 0.01]. FMD did not change at six months (4.38±0.83 %; p=0.72) or one year after parathyroidectomy (5.07±0.74 %; p=0.49).

In a pre-specified analysis, the subgroup of patients with abnormal baseline FMD (<2.2%; N=15) was examined. Those with abnormal baseline FMD tended to have somewhat higher blood pressure (systolic mean ± SE: 129 ± 4 vs 120 ± 3 mm Hg, p = 0.05; diastolic: 79 ± 3 versus 72 ± 2 mm Hg, p = 0.05), but did not differ in other cardiovascular risk factors (age, gender, BMI, past or current tobacco use, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, history of myocardial infarction; fasting glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, or c-reactive protein levels). Nor did tertile analysis of continuous CV risk factors reveal an explanation for the low FMD (ie those in the lowest tertile of FMD weren’t those in the highest tertile of blood pressure, cholesterol, etc.). Subjects with abnormal FMD also did not differ with regard to baseline serum calcium, PTH, and 25OHD from those with normal FMD (calcium: 2.63 ± 0.03 vs. 2.65 ± 0.03 mmol/L, p=0.32; PTH: 10.5 ± 1.8 vs. 10.4 ± 0.7 pmol/L, p=0.98; 25OHD: 75 ± 5 vs. 67 ± 5 nmol/L, p=0.43). Nor was FMD in this group associated with baseline levels of serum calcium (r=−0.05, p=0.84), PTH (r=−0.10, p=0.72), or 25OHD (r=0.02, p=0.94). However, endothelial function improved after parathyroidectomy in those with abnormal baseline values (Figure 1). By 6 months after surgical cure, mean FMD was no longer low (baseline: 0.81 ± 0.19%, 6 month: 3.18±0.79%; p=0.02). The improvement in FMD persisted at 1 year, representing a 350% increase in FMD after parathyroidectomy (12 month FMD 3.68 ± 1.22%; p=0.04). One year after cure, 8 subjects had normal FMD. The improvement in FMD was not associated with the decline in calcium or PTH levels, or with the increase in 25OHD. Nor were there other changes known to affect FMD in these patients (p= NS for all): there was no improvement in blood pressure (systolic BP: baseline 129 ± 4, 12 month 129 ± 3 mm Hg; diastolic BP: baseline 79 ± 3, 12 month 79 ± 2 mm Hg); BMI (baseline 25.8 ± 0.9, 12 month 26.2 ± 0.8 kg/m2), insulin sensitivity (fasting glucose baseline 5.3 ± 0.2, 12 month 5.2 ± 0.2 mmol/L; fasting insulin baseline 42.3 ± 10.0, 12 month 84.7 ± 32.3 pmol/L), total cholesterol (baseline: 5.4 ± 0.2, 12 month: 5.6 ± 0.3 mmol/L), or hsCRP (baseline: 1.52 ± 0.30, 12 month: 2.42 ± 0.49 mg/L). Only one subject had a change in medication during the study that may have contributed to the improvement in FMD (addition of ezetimibe). Exclusion of this subject from the analysis did not alter the results.

Figure 1.

Comparison of baseline and 12 months FMD in those with normal (N=30) versus abnormal (FMD < 2.2%; N=15) baseline FMD.

In the 30 patients with normal baseline FMD, no change over time was observed (Figure 1). Of the two-thirds of subjects with normal baseline FMD, those in the highest tertile had a 32% decline (p=0.04) while those in the middle tertile had a 32% increase (p=0.29) in FMD, all within the normal range. The significant difference between those with abnormal and normal FMD at baseline (p<0.001) disappeared by 6 months (p=0.20), and FMD values remained similar at 1 year (p=0.12; linear mixed model analyses).

Discussion

Both excess calcium and PTH have been proposed as possible causes of endothelial dysfunction in PHPT. This report assessed FMD in a cohort with lower serum calcium levels and PTH levels, one-half to one-quarter those in prior studies. In these subjects with very mild PHPT, endothelial function was normal at baseline and unchanged at six months and one year after parathyroidectomy. However, in the one-third of patients with endothelial dysfunction at baseline, mean FMD normalized by 6 months postoperatively.

Acute hypercalcemia causes a dose-dependent impairment in endothelial function,(15) and in prior studies, impaired FMD in PHPT appears related to the degree of hypercalcemia. Most (7, 8, 16) but not all studies (17) of patients with mean calcium levels around 3 mmol/L have reported abnormal endothelial function and some studies have demonstrated a negative correlation with calcium.(16, 18) The much milder hypercalcemia in our cohort may explain the normal FMD in our subjects. However, even in those with abnormal FMD, impairment in endothelial function was not related to the degree of hypercalcemia, though this subgroup was small.

There are limited data suggesting that PTH may cause impaired endothelial dysfunction in PHPT. While short-term administration of PTH causes a dose-dependent transient vasodilation, chronic continuous PTH infusion results in vasoconstriction and hypertension.(19, 20) PTH, even within the normal range, has been prospectively associated with cardiovascular mortality (21) and increased PTH levels are independently associated with impaired endothelial function in elderly men with CHF.(22) Although one study reported that PTH independently predicted lower FMD in PHPT, the mean PTH in that report was four times higher than in our cohort, making it impossible to generalize the results to those with mild disease.(18)

Finally, some studies in subjects without PHPT have reported an association between abnormal FMD and vitamin D deficiency (23) and improvement with vitamin D repletion.(24) Although this is the first study of FMD in PHPT to include 25OHD data, we found no such association; if anything, the vitamin D deficient patients had higher FMD than those who were replete. The fact that so few of our patients were frankly vitamin D deficient may have prevented us from detecting a relationship. Nor was the improvement in FMD in subjects with abnormal values associated with the increase in 25OHD levels. While mean vitamin D levels increased into the normal range, likely due to postoperative supplementation, most vitamin D deficient patients were still not replete at 12 months.

Our finding, that mean FMD did not improve in the cohort as a whole, is similar to most but not all studies.(7, 9, 18) Improvement could have been masked by the slight but significant increase in BMI and diastolic blood pressure, both factors known to negatively impact FMD. It is difficult to compare our results to those of prior studies in which reported cardiovascular risk factor profiles were either very different or unknown. However, only approximately 15% of the variability in FMD is explained by classic cardiovascular risk factors. (25) Heritability of FMD is also modest (0.17 in our study,(26) and 0.14 heritability estimate in the Framingham Offspring Study(25)). Thus, genetic and traditional cardiovascular risk factors explain only part of the variance in FMD. In our cohort, those with abnormal and normal FMD differed in baseline blood pressure, but had similar cardiovascular risk profiles and PHPT severity, supporting the hypothesis that additional unaccounted for factors are likely to influence FMD. Differences in technique used to assess FMD could also explain discrepant results.(13)

Others have also reported that patients with impaired FMD had significant improvement following parathyroidectomy.(7, 18) Data in non-hyperparathyroid populations suggest that a change of the magnitude we observed could be clinically meaningful. Improved FMD is associated with fewer cardiovascular events in those with treated hypertension and coronary artery disease.(27, 28) The 350% post-parathyroidectomy improvement compares favorably to responses to other clinically meaningful cardiovascular interventions. These include an increase in FMD of 66% when fenofibrate is added to statin-treated type 2 diabetics,(29) of 168% with combined fluvastatin and valsartan treatment,(30) and of 157% in the subset of patients whose FMD improved after optimized medical therapy for coronary artery disease (with subsequent decrease in cardiovascular events).(28) While it is possible that the increase in FMD in those with abnormal endothelial reactivity represents regression to the mean, those with abnormal FMD at baseline showed an overall group mean improvement of 350% over their mean at baseline and the average within-subject difference improved by 2.849 units (95% CI: 0.289 – 5.410, SE 1.195, p = 0.032), which we believe is likely to be clinically significant.

Finally, our finding that FMD is not abnormal in mild PHPT is consistent with the hypothesis that the effect of mild disease on different vascular beds is not uniform. This and other cohorts of patients with mild PHPT have had subclinical cardiovascular disease in other vascular beds, including increased aortic(31, 32) and carotid stiffness(10) and increased aortic valve calcification area.(33) These abnormalities were linearly associated with PTH concentration, while increased carotid intima media thickness was not. (10, 31, 33)

Our study was limited by its relatively small size, use of a convenience sample of patients with PHPT, and the lack of a longitudinal control group. Although FMD improved after cure in those with baseline abnormal FMD, we cannot definitively attribute the improvement to parathyroidectomy. Our study would have also benefited from having subjects with a broader range of 25OHD levels. Despite these limitations, this study has several notable strengths, including its prospective design, the homogeneity of mild PHPT in the cohort, and the availability of data on cardiovascular risk factors and 25OHD levels.

In summary, endothelial function as measured by FMD was normal in patients with mild PHPT and very modest elevations in serum calcium levels and did not change after parathyroidectomy. However, those patients with baseline endothelial dysfunction did improve significantly and to an extent that is likely to be clinically meaningful. The small number of patients with abnormal FMD, and the absence of an association with the biochemical hallmarks of the hyperparathyroid process do not support the measurement of FMD in patients with mild PHPT, nor do they support using FMD results as an indicator for parathyroidectomy. Instead, the data suggest a direction for future research. At the current time one must conclude that more data are needed regarding endothelial dysfunction in PHPT in order to warrant a change in surgical guidelines for parathyroidectomy.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK066329, K24 DK074457

Footnotes

Disclosure summary: All authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wermers RA, Khosla S, Atkinson EJ, Grant CS, Hodgson SF, O'Fallon WM, et al. Survival after the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism: a population-based study. Am J Med. 1998 Feb;104(2):115–22. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundgren E, Lind L, Palmer M, Jakobsson S, Ljunghall S, Rastad J. Increased cardiovascular mortality and normalized serum calcium in patients with mild hypercalcemia followed up for 25 years. Surgery. 2001 Dec;130(6):978–85. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu N, Donnan PT, Flynn RW, Murphy MJ, Smith D, Rudman A, et al. Increased mortality and morbidity in mild primary hyperparathyroid patients. The Parathyroid Epidemiology and Audit Research Study (PEARS) Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010 Jul;73(1):30–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedback G, Tisell LE, Bengtsson BA, Hedman I, Oden A. Premature death in patients operated on for primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg. 1990 Nov-Dec;14(6):829–35. doi: 10.1007/BF01670531. discussion 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Johnson C, Polak JF, Post W, et al. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009 Aug 11;120(6):502–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder S, Enderle MD, Ossen R, Meisner C, Baumbach A, Pfohl M, et al. Noninvasive determination of endothelium-mediated vasodilation as a screening test for coronary artery disease: pilot study to assess the predictive value in comparison with angina pectoris, exercise electrocardiography, and myocardial perfusion imaging. Am Heart J. 1999 Oct;138(4 Pt 1):731–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosch M, Hausberg M, Vormbrock K, Kisters K, Gabriels G, Rahn KH, et al. Impaired flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism improves after parathyroidectomy. Cardiovasc Res. 2000 Sep;47(4):813–8. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosch M, Hausberg M, Vormbrock K, Kisters K, Rahn KH, Barenbrock M. Studies on flow-mediated vasodilation and intima-media thickness of the brachial artery in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Hypertens. 2000 Jul;13(7):759–64. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neunteufl T, Heher S, Prager G, Katzenschlager R, Abela C, Niederle B, et al. Effects of successful parathyroidectomy on altered arterial reactivity in patients with hypercalcaemia: results of a 3-year follow-up study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000 Aug;53(2):229–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker MD, Fleischer J, Rundek T, McMahon DJ, Homma S, Sacco R, et al. Carotid vascular abnormalities in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Oct;94(10):3849–56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker MD, Fleischer JB, Di Tullio MR, Homma S, Rundek T, Stein EM, et al. Cardiac structure and diastolic function in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 May;95(5):2172–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimbo D, Grahame-Clarke C, Miyake Y, Rodriguez C, Sciacca R, Di Tullio M, et al. The association between endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes in a population-based multi-ethnic cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2007 May;192(1):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bots ML, Westerink J, Rabelink TJ, de Koning EJ. Assessment of flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMD) of the brachial artery: effects of technical aspects of the FMD measurement on the FMD response. Eur Heart J. 2005 Feb;26(4):363–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimbo D, Muntner P, Mann D, Viera AJ, Homma S, Polak JF, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and the risk of hypertension: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2010 May;55(5):1210–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson IL, Rastad J, Johansson K, Lind L. Endothelial vasodilatory function and blood pressure response to local and systemic hypercalcemia. Surgery. 2001 Dec;130(6):986–90. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baykan M, Erem C, Erdogan T, Hacihasanoglu A, Gedikli O, Kiris A, et al. Impairment of flow mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2007 Jun;23(3):323–8. doi: 10.1007/s10554-006-9166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neunteufl T, Katzenschlager R, Abela C, Kostner K, Niederle B, Weidinger F, et al. Impairment of endothelium-independent vasodilation in patients with hypercalcemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1998 Nov;40(2):396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekmekci A, Abaci N, Colak Ozbey N, Agayev A, Aksakal N, Oflaz H, et al. Endothelial function and endothelial nitric oxide synthase intron 4a/b polymorphism in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009 Jul;32(7):611–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03346518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rambausek M, Ritz E, Rascher W, Kreusser W, Mann JF, Kreye VA, et al. Vascular effects of parathyroid hormone (PTH) Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;151:619–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4259-5_64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hulter HN, Melby JC, Peterson JC, Cooke CR. Chronic continuous PTH infusion results in hypertension in normal subjects. J Clin Hypertens. 1986 Dec;2(4):360–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagstrom E, Hellman P, Larsson TE, Ingelsson E, Berglund L, Sundstrom J, et al. Plasma parathyroid hormone and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in the community. Circulation. 2009 Jun 2;119(21):2765–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loncar G, Bozic B, Dimkovic S, Prodanovic N, Radojicic Z, Cvorovic V, et al. Association of increased parathyroid hormone with neuroendocrine activation and endothelial dysfunction in elderly men with heart failure. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011 Mar;34(3):e78–85. doi: 10.1007/BF03347080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jablonski KL, Chonchol M, Pierce GL, Walker AE, Seals DR. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with inflammation-linked vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension. 2011 Jan;57(1):63–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarcin O, Yavuz DG, Ozben B, Telli A, Ogunc AV, Yuksel M, et al. Effect of vitamin D deficiency and replacement on endothelial function in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Oct;94(10):4023–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Mitchell GF, Vasan RS, Keaney JF, Jr, et al. Clinical correlates and heritability of flow-mediated dilation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004 Feb 10;109(5):613–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112565.60887.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki K, Juo SH, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Disla N, Liu R, et al. Genetic contribution to brachial artery flow-mediated dilation: the Northern Manhattan Family Study. Atherosclerosis. 2008 Mar;197(1):212–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modena MG, Bonetti L, Coppi F, Bursi F, Rossi R. Prognostic role of reversible endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Aug 7;40(3):505–10. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitta Y, Obata JE, Nakamura T, Hirano M, Kodama Y, Fujioka D, et al. Persistent impairment of endothelial vasomotor function has a negative impact on outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Jan 27;53(4):323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamilton SJ, Chew GT, Davis TM, Watts GF. Fenofibrate improves endothelial function in the brachial artery and forearm resistance arterioles of statin-treated Type 2 diabetic patients. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010 May;118(10):607–15. doi: 10.1042/CS20090568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lunder M, Janic M, Jug B, Sabovic M. The effects of low-dose fluvastatin and valsartan combination on arterial function: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Intern Med. 2012 Apr;23(3):261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubin MR, Maurer MS, McMahon DJ, Bilezikian JP, Silverberg SJ. Arterial stiffness in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jun;90(6):3326–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JC, Page MD, John R, Wheeler MH, Cockcroft JR, Scanlon MF, et al. Augmentation of central arterial pressure in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Oct;85(10):3515–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwata S, Walker MD, Di Tullio MR, Hyodo E, Jin Z, Liu R, et al. Aortic valve calcification in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jan;97(1):132–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]