Abstract

While there is strong evidence in support of geriatric depression treatments, much less is available with regard to older U.S. racial and ethnic minorities. The objectives of this review are to identify and appraise depression treatment studies tested with samples of U.S. racial and ethnic minority older adults. We include an appraisal of sociocultural adaptations made to the depression treatments in studies meeting our final criteria. Systematic search methods were utilized to identify research published between 1990 and 2010 that describe depression treatment outcomes for older adults by racial/ethnic group, or for samples of older adults that are primarily (i.e., >50%) racial/ethnic minorities. Twenty-three unduplicated articles included older adults and seven met all inclusion criteria. Favorable depression treatment effects were observed for older minorities across five studies based on diverse settings and varying levels of sociocultural adaptations. The effectiveness of depression care remains mixed although collaborative or integrated care shows promise for African Americans and Latinos. The degree to which the findings generalize to non-English-speaking, low acculturated, and low income older persons, and to other older minority groups (i.e., Asian and Pacific Islanders, and American Indian and Alaska Natives) remains unclear. Given the high disease burden among older minorities with depression, it is imperative to provide timely, accessible, and effective depression treatments. Increasing their participation in behavioral health research should be a national priority.

Keywords: Depression, Treatment, Minorities, Systematic Review, Sociocultural Adaptations

INTRODUCTION

Older adults and racial and ethnic minorities are currently two of the fastest growing demographic groups in the U.S., with an estimated growth between 2010 and 2050 of approximately 97% and 115%, respectively(1,2). It is estimated that by 2050, older adults ages 60+ will comprise nearly 26% of the total population(2), while racial/ethnic minorities will reach a numerical majority of 54%(1). Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders among older adults including ethnic and racial minorities(3–9), and is considered to be a leading cause of disease burden and disability in the U.S. and abroad(10–12).

Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for depression have been found to be effective among older adults(13–19). A Cochrane review(17) found tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors to be effective in comparison to placebos in institutionalized and community patients. Other reviews and consensus statements have found second generation antidepressants (non-TCAs) to be more effective than placebo among older adults(15, 20), and SSRIs to be the top-rated antidepressants for all types of depression, with highest ratings for tolerability and efficacy(13, 14). Nonpharmacological treatments, such as cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, problem solving therapy or treatment (PST), interpersonal therapy, reminiscence therapy, bibliotherapy, and brief psychodynamic therapy have also been shown to be effective among older adults but with varying levels of evidence(14, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22). Approaches incorporating a combination of treatments (e.g., pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic, care management, and/or psychoeducation) and collaborative care models have been effective in treating late life depression(23–25), and are recommended by expert consensus(14).

While there is evidence to support geriatric depression treatments, much less is available regarding the generalizability of this evidence to older U.S. racial and ethnic minorities. Thus, the effectiveness of depression care remains unclear for this population which is quite diverse in terms of socioeconomic status, nativity, ancestry, language preferences, immigration history and legal status, acculturation, neighborhood contexts, sociopolitical history, and so forth. This is in light of the fact that older minorities with depression report higher levels of impairment and are more persistently ill than non-Hispanic white older adults(26, 27), yet have lower utilization of mental health care(28, 29).

In the last decade there has been an impetus toward the transformation of mental health care in the U.S. to increase the adoption of evidence-based practices by organizations that deliver behavioral health services(30). Yet, many proponents of culturally competent research and practice question the sociocultural validity of evidence-based practices given that the inclusion of culturally and linguistically diverse older minorities in mental health research has historically been low(31–34). Moreover, prior evidence suggests that older minorities may express psychological distress differently than non-Hispanic whites. To illustrate, African Americans may present with unique symptom profiles of emotional disorders such as less characterization of depression by dysphoric mood, suicidal thoughts, agitation or anxiety(35), and less reports of thoughts of death (non-suicidal thoughts)(36). Thus, assessment and treatment protocols may not capture an adequate picture of symptom presentation, culture-bound explanatory models, and sociocultural experiences with stressors as well as mental health care(26). Second, others have speculated that cultural differences in terms of collectivistic vs. individualistic world views among Asian Americans may account for lower comorbid anxiety rates given the importance placed on maintaining harmonious relationships and overall well-being in these groups(37, 38).

Taken together, we address the need to document the extent to which the depression treatment literature addresses group-specific treatment outcomes of U.S. racial and ethnic minorities, and what sociocultural adaptations, if any, were instituted in the treatment regimen. The current study addresses three objectives. The first objective is to identify and describe studies that report depression treatment outcomes for U.S. racial and ethnic minority older adults, hereafter referred to as older minorities. The second objective is to appraise the level of evidence and depression outcomes for the studies that meet the systematic review criteria. The third objective is to appraise the sociocultural adaptations that were made to the depression treatment. In this article, sociocultural adaptations (hereafter called adaptations) refer to modifications to the treatment itself or to recruitment or delivery strategies that address any one or a combination of the following: access, retention, acceptability, adherence, effectiveness, and satisfaction with treatment. Typically tailored to a group’s traditional world views and behaviors (e.g., values and beliefs, traditions and customs, communication patterns, sociohistorical context)(39, 40), these modifications are purported to increase the cultural fit between the treatment strategies and the individual’s world view around illness, wellness, help-seeking, and treatment for psychiatric disorders(41).

METHODS

Search Strategy

In early 2011, we searched five electronic databases for peer-reviewed articles published in the previous two decades that examined depression treatment outcomes among older minorities. Additionally, we consulted with experts in the field, conducted electronic searches based on the search engines of four mental health journals using similar key words, and manually searched through the reference lists of 18 review articles focused on depression treatment in older adults (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of Search Process and Results by Database Source and Parameters.

| Source | Search Terms | Other parameters | Results* |

|---|---|---|---|

| PUBMED | Depression [MeSH Major Topic]** | MeSH | 226 articles |

| Depressive disorder [MeSH Major Topic] | MeSH Major Topics | ||

| Psychotherapy [MeSH Major Topic] | All terms were exploded | ||

| Mental health services [MeSH Major Topic] | |||

| Antidepressive agents [MeSH Major Topic] | |||

| Psychiatric somatic therapies [MeSH Major Topic] | |||

| Complementary therapies [MeSH Major Topic] | |||

| Ethnic groups [MeSH] | |||

| Minority groups [MeSH] | |||

| Continental population groups [MeSH] | |||

| PsycINFO | Depression emotion | Descriptors (DE) | 361 articles |

| Major depression | Journals only | ||

| Treatment | English only | ||

| Racial and ethnic groups | All terms were exploded | ||

| Racial and ethnic differences | |||

| Social Services Abstracts | Depression psychology | Descriptors (DE) | 19 articles |

| Treatment | English only | ||

| Ethnic groups | Earliest to 2010 | ||

| Cultural groups | Articles only | ||

| Minority groups | All terms were exploded | ||

| Race | |||

| Social Work Abstracts | Depression | Subject (SU) | 56 articles |

| Ethnic groups | Boolean/Phrase | ||

| Cultural groups | Journals only | ||

| Minority groups | All terms were exploded | ||

| Latino or Hispanic | |||

| African American or black | |||

| Native American or American Indian | |||

| Asians | |||

| Web of Knowledge, Social Sciences Citation Index | Depression or major depression | Topics (TS) | 542 articles (10 of these articles were added as a result of a previous, less specific search in this database) |

| Treatment | English only | ||

| Treatment outcomes | Articles only | ||

| Ethnic groups | Databases=SSCI | ||

| Minority groups | All terms were exploded | ||

| Cultural groups | |||

| Race | |||

| American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry; International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry; Journal of Mental Health and Aging; and Journal of Psychiatric Services | Depression | Key Words entered as search terms in each journal’s website | 18 review articles for reference list manual search; |

| Depressive disorder | |||

| Treatment | |||

| Intervention | |||

| Minority | 3 additional articles reporting depression treatment outcomes for older minorities | ||

| Review or systematic review*** | |||

| Meta analysis*** |

Results are not mutually exclusive across all sources. Duplicate articles were found across databases and journals searched.

MeSH = Medical Subject Headings

These search terms were entered only into search engines of the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were established a priori and applied to each article in our review.

Inclusion Criteria

-

1

The article was published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 1990 and December 2010;

-

2

The study sample was recruited from within the U.S. and its territories;

-

3

Racial and ethnic minority groups were defined according to the Supplement to the Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health(9). Therefore, studies focused on any one or a combination of the following four minority groups met inclusion criteria: African-American/Black, Hispanic/Latino (hereafter referred to as Latinos), Asian and Pacific Islander (hereafter referred to as Asian Americans), and American Indian and Alaska Native.

-

4

The study reported primary research on depression treatment, where depression diagnostic criteria and outcomes were defined either by standardized structured interviews or symptomatology scales;

-

5

The study reported depression treatment outcomes separately by minority group, or outcomes were reported for a total sample comprised of >50% minorities. For the latter, we excluded studies that did not meet the >50% minority threshold since low ethnic heterogeneity in the sample may not provide reasonable confidence of treatment effects for the minority groups studied;

-

6

If the article met these criteria, it was further assessed for inclusion of older adults. Studies that reported a sample with mean age of ≥60 or an age range that included ages ≥60 were further examined.

Exclusion Criteria

-

7

Depression treatment outcomes for older minorities were not explicitly reported although the authors reported recruitment criteria that may have included older minorities; and

-

8

Prevention studies, reviews, meta-analyses, dissertations, reports, meeting abstracts, and case studies or series were excluded.

In sum, final inclusion of an article was determined by the presence of depression treatment outcomes reported for a sample of older minorities of at least 60 years of age, or for an elderly minority sample as defined by the authors.

Procedures

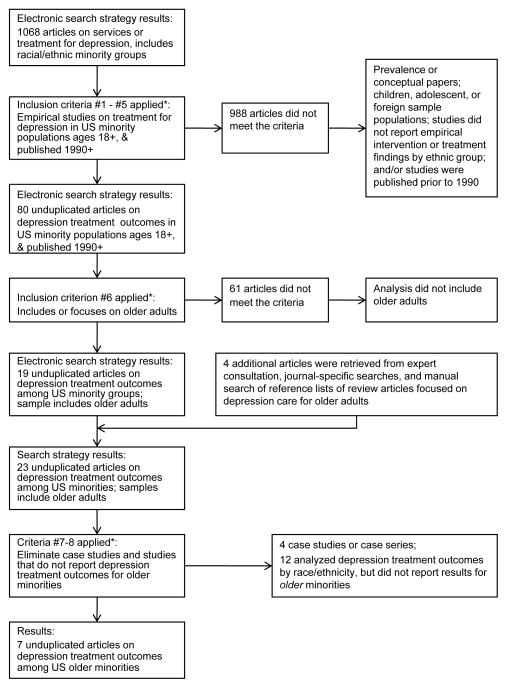

Figure 1 describes the study selection procedures. At the initial level, abstracts were screened for eligibility. Articles that met criteria and articles in question were retrieved and reviewed by the authors. Second, information about the patient population, setting, study design, intervention, culture-bound syndromes or culture-specific symptom presentation, adaptations, depression outcome measures, follow-up, retention, data analysis, and results were systematically abstracted from each article. To appraise each study’s level of evidence, we used validity criteria established by the American Medical Association’s Evidence Based Medicine Working Group(42): randomization, complete follow-up, blind-rated outcomes, clinically equivalent groups, and equally treated groups.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection. *Refers to inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in the methods section.

To examine the extent that the interventions were modified for increasing cultural appropriateness or acceptability, we used criteria developed by Bernal and his associates(41). Their framework offers the following eight dimensions as foci in the tailoring of services to increase cultural sensitivity(41, 43): language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context. Although not mutually exclusive, these dimensions represent general areas of an intervention that are amenable to adaptation strategies. For example, the content and/or delivery of an intervention (method) can be adapted through the use of narratives or cuentos (storytelling) and refranes (sayings, proverbs) in counseling encounters with Latinos which exemplifies an adaptation to the intervention dimensions of content, method, and metaphors(43, 44). We first described the adaptations that were explicitly mentioned or referenced in the primary study or earlier publications. Then we appraised which of the eight dimensions corresponded to the adaptations made to each study. All abstracted data were then summarized, compared, and contrasted.

RESULTS

The comprehensive search identified nearly 82,000 studies that focused on depression, over 16,000 that addressed depression treatment, and 1,068 among broadly defined minority populations. Of the 1,068 unduplicated articles, 80 reported depression treatment outcomes by minority group or for a sample comprised of greater than 50% racial or ethnic minorities, and 19 of these included older adults. Four additional articles were identified through expert consultation, key word searches in four specific mental health journals, and a manual search of reference lists of 18 review articles on depression treatment in older adults. Of the combined 23 articles, 16 were excluded for the following reasons: four were case studies or case series and 12 studies did not report outcomes specifically for older minorities.

This search identified five studies(45–49) that reported depression treatment outcomes for a population of older minorities ages ≥60. An additional two articles were identified(50, 51) that reported depression treatment outcomes for an elderly minority sample as defined by the authors (i.e., age 50+ and age 55+, respectively) with mean age scores over 60 years. Thus, seven studies met inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (see Table 2). In one study(46), we focused only on the analyses conducted for depression and not other psychiatric diagnoses which were also addressed in the study. Focusing only on the depression outcomes allowed the study to meet the 50% minority group cut-off of our inclusion criteria. To increase the thoroughness of the review, we extracted additional information provided by related articles(52, 53) for two studies(46, 48).

Table 2.

Studies that Report Depression Treatment Outcomes for Minority Older Adults

| Study/Year | Population/Setting | Depression-Related Objective | Protocol/Intervention | Depression Outcomes | Design | Similar Groups at Baseline | Equally Treated Groups | Follow-up/Drop-out | Data Analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areán et al. /2005 | 1748 participants age 60+ in primary care settings; Mean age = 71.2 years; 1131 women; 222 African American; 138 Latino; 1388 NHW |

To test if a collaborative care model is as effective in improving depression in older minorities as with NHW. | Exp: Collaborative stepped care approach included antidepressant medication, PST-PC, educational materials, and support/monitoring provided by depression clinical specialists. Control: usual care. |

HSCL-20 score; complete remission (HSCL-20 score < 0.5), response (≥50% HSCL-20 reduction) | Multi-site RCT; Blind-rated. | yes | yes | Follow-up: 3, 6, and 12 months post baseline. Drop-out: 10%, 13%, and 17% at 3, 6, and 12 months. |

Intent-to-treat; Multiple imputation technique. | Collaborative care was as effective in improving depression outcomes in older minorities as NHW at 12 months. |

| Areán et al. /2008 | 1524 participants age 65+ in primary care settings; Mean age = 73.9 years; 467 women**; 404 African American; 280 Latino; 105 Asian; 48 other; 687 NHW. |

To compare MH/SA service integration to brokerage care management depression* treatment outcomes for older minorities and NHW. | Exp: MH/SA (i.e., antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, case management, and brief behavioral alcohol intervention) were integrated in primary care. Specific algorithms not followed. Brokerage case management: Primary care provider conducted initial evaluation and referred to MH/SA services and social services in a separate location. | CES-D score | Multi-site RCT; Not blind-rated** | yes** | yes | Follow-up: 3 and 6 months post baseline. Drop-out: 20% at 6 months. |

Intent-to-treat; Mixed effects regression models across time points. | No significant depression treatment outcomes were found at 6 months although access to depression care was enhanced for all groups. |

| Bogner & de Vries /2010 | 58 participants, ages 50–80 in primary care setting; Mean age = 60.2 years; 49 women; All African American. | To examine whether integrating depression treatment into care for Type 2 diabetes improves depression and diabetes outcomes. | Exp: Integrated care manager liaised between physician and patient, and conducted individualized in-person sessions and phone monitoring contacts to provide education and support in medication adherence, monitor side effects, and assess progress. Control: Usual care. | CES-D score | RCT; Not blind-rated. | yes | yes | Follow-up: 12 weeks post baseline. Drop-out: 0% |

All available data. No missing cases. | Integrated depression & diabetes care was more effective than usual care in improving depression outcomes. Experimental group reported fewer depressive symptoms at 12-weeks. |

| Ell et al. /2010 | 1081 participants ages 18–97 in pooled analysis of 2 primary care settings, and 1 home care setting; Subsample of 440 older adults ages 60–97, mean age = 71.6 years includes 331 women; 214 Latinos; 26 African Americans; 7 Asians; 187 NHW; and 6 other. | To compare effectiveness of collaborative care for depression between older and younger adults with comorbid illness. | Exp: Collaborative stepped care approach included antidepressant medication, PST-PC, educational materials, and support/monitoring provided by depression clinical specialists who provided monthly telephone monitoring, relapse prevention, and navigation of community and care systems. Optional open-ended PST support group was offered in the cancer and diabetes trials, but not the home care trial. Control: Participants in enhanced usual care received educational pamphlets on depression. Patients from cancer and diabetes trials were provided with community resource lists. | 50% PHQ-9 reduction from baseline. | Pooled data of 3 RCTs; Blind-rated. | Not explicit between Exp and Control groups | yes | Follow-up: 6 or 8 months, & 12 months post baseline. Drop-out: Among older adults, 35.5% & 42.3% dropped out at 6- and 12-months respectively |

Intent-to-treat; Sensitivity analysis to compare results using all-available raw data & imputed data. | Compared to patients in usual care, patients in collaborative care had significantly greater improvements at 6-months regardless of age. There were no significant differences in reducing depression symptoms between older and younger patients. |

| Husaini et al. /2004 | 303 participants in subsidized high-rise apartments, ages 55–90 years; Mean age = 73.7 years. All women. 121 African American; 182 NHW | To examine the effectiveness of group therapy in reducing depressive symptoms, and to explore the effects of the program by age, race, and level of depression prior to treatment. | Exp: 6-week, 12-session group therapy program. Modules include cognitive and re-motivation therapy, exercise and preventive health behaviors, management of chronic medical conditions, reminiscence and grief therapy, and social skills development. Control: no program. |

GDS-15 score | Quasi-experimental. Not known if blind-rated. | African American, but not NHW participants were similar | Yes | Follow-up: 3 and 6 months post-program. Drop-out: 4% at 3 months and unreported at 6 months. |

Analysis of missing data not explicitly reported. | There were no main or interaction effects for African Americans with or without depression prior to treatment, or by age group. NHWs in treatment did better than those in the control group. NHWs ages 55–75 did better than those 76+. |

| Lichtenberg /1997 | 41 participants, age 60+ in inpatient rehabilitation hospital; 37 in analysis; Mean age = 78 years; 31 women; 32 African American; 5 NHW*** |

To evaluate if an inpatient depression treatment program reduces depression. | Subjects were assigned to groups in cohorts. Cohort 1: behavioral treatment sessions (30 minute sessions 2x/week) delivered by geropsychologist. Cohort 2: behavioral treatment sessions (daily, coincident with occupational therapy sessions) delivered by occupational therapists. Depression treatment sessions include relaxation & imagery, pleasurable events, mood ratings, and positive social praise. Cohort 3: no intervention comparison group. |

GDS-30 score | Quasi-experimental. Not known if blind-rated. | yes | Cohorts 1 and 2 vary by more than one variable | Follow-up: Post-study assessment conducted within 24 hours prior to discharge from rehab hospital. Drop-out: 9.8% (4 subjects) |

Drop-outs were not included in analysis. | Behavioral treatments for depression are effective in improving depression outcomes in older inpatients provided by either interventionist. |

| Quijano et al. /2007 | 94 participants, age 60+ in 3 community based service agencies; Mean age = 72.5 years; 74 women; 19 African American; 41 Latino; 2 Other; 32 NHW; 74 female | To evaluate an evidence-based depression intervention for frail older adults. | Subjects provided four treatment components provided by case managers: (1) screening and assessment; (2) education; (3) referral and linkage; and (4) behavioral activation (helping client identify an activity that fit with his/her values and monitoring the client’s progress in implementing their activity goals). | GDS-15 score | Pre-experimental. Not blind-rated. | N/A | N/A | Follow-up: 3 and 6 months post baseline. Drop-out: 22.3% and 28.7% at 3-and 6-months respectively |

Drop-outs were not included in analysis. | There was a significant reduction in depression severity from baseline to 6-months. |

Note: NHW = non-Hispanic white; Exp = experimental; HSCL = Hopkins Symptom Checklist; MH/SA = mental health and service abuse; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire

Includes only the subsample of participants with depressive disorder

Reported in related study (52)

Reported in related article (53)

Setting and Types of Interventions

Studies included data from one or more of the following treatment settings: primary care clinics(45–47, 50), social services agencies(49), inpatient settings(48), subsidized housing(51), and home care(47).

Four randomized trials involved integrated or collaborative care models emphasizing the integration of depression treatment into primary care and home care settings(45–47, 50) using a wide range of program components to deliver pharmacological and psychosocial interventions. The two studies conducted by Areán and her colleagues(45, 46) were secondary analyses of large-scale studies comprised of diverse older respondents in primary care settings (IMPACT(24) and PRISM-E(54)). Bogner and de Vries(50) examined depression outcomes in a primary care diabetes-related treatment program geared exclusively to African Americans. The study by Ell and associates(47) compared younger vs. older respondents in a pooled analyses of three collaborative care studies based on one home health care system and two primary care safety net clinics that provide service to poor and uninsured populations. The three remaining studies incorporated group therapy for women in subsidized housing(51), behavioral treatment for inpatient rehabilitation patients(48), and community-based interventions for frail older adults in senior programs(49).

All interventions included an array of components or treatment approaches. Most studies were multisystemic interventions directed to the individual and linkage to multiple service systems. For example, five interventions included distinct combinations of referral and linkage or case management across service systems(45–47, 49, 50), pharmacotherapy(45–47, 50), psychoeducation(45, 47, 49, 50), brief behavioral alcohol intervention(46), and Problem Solving Treatment or Therapy(45, 47), or other type of psychotherapy(46), and/or behavioral activation(49). Other studies directed the intervention only to the individual by using group therapy modules(51) and depression treatment sessions(48) with various techniques such as cognitive therapy, exercise, reminiscence and grief therapy, management of medical conditions and social skills development, relaxation and imagery, pleasurable events, mood ratings, and positive social praise.

Patient Characteristics

Collectively, the seven studies included 882 African American, 673 Latino, and 112 Asian American older adults. All study samples included African Americans in their samples, while four included Latinos(45–47, 49) and two included Asian Americans(46, 47). None of the seven studies specified the inclusion of American Indian/Alaska Natives. With the exception of two studies that described their sample of Latinos as primarily of Mexican origin(45, 49), the four other studies that included Latinos and/or Asian Americans did not further characterize these diverse populations by ethnic or racial subgroup. Non-Hispanic whites were analyzed as a comparison group in two studies(45, 46), analyzed separately (not as comparison group) from minorities in one study(51), and were included with minorities in the analyses of three studies whose older adult samples were composed primarily of minorities(47–49). The average age of study participants was in the 70’s for all except one study(50)whose participants’ age ranged from 50 to 80 and averaged 60.2 years. In the study by Ell and colleagues(47), treatment effects were compared between older and younger minorities with mean age of 71.6 and 46.9 years, respectively. All but one study(46) reported samples predominantly comprised of females.

Depression Diagnostic Criteria and Outcome Measures

With respect to depression diagnostic criteria (not shown in table), six studies used symptomatology scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)(48, 49, 51), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)(50), the depression modules of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)(47), and the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview(46). Only one study relied on structured diagnostic interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)(45). While two studies(47, 48) included only persons with severe symptomatology, the remaining studies included a wider range of depression severity including mild or minor depression(46, 49, 51), dysthymia(45, 46), depression NOS(46), and an unspecified range of depressive symptoms(50). None of the studies reported potential diagnostic considerations with regard to culture-specific symptom presentation or culture bound syndromes.

Turning to treatment outcomes, we found that depression outcomes were based solely on symptomatology scales. Five studies utilized the same depression measure for assessing outcomes as they did for assessing diagnostic inclusion criteria(47–51). None of the studies reported the selection of depression measures based on previous work indicating cultural suitability.

Level of Evidence

All of the studies reported using manualized interventions or research protocols although the details of such were not available for all manuals cited. At the highest level of methodological quality were four randomized controlled trials(45–47, 50) which reported sample sizes from 58 to 1748. A potential source of assessment bias exists for one(46)of the four RCTs, as blind assessors were not used to measure depression outcomes. Only three RCTs(45–47) reported intent-to-treat analysis, and 6-month post-baseline drop-out rates for older adults of 13%, 20%, and 35.5%, respectively. Two studies(45, 47) reported outcomes at 12-months, with respective drop-out rates of 17% and 42.3%. Statistically similar experimental and comparison groups at baseline were evident in three RCTs(45, 46, 50). However, in the study by Ell and colleagues(47) baseline data was reported by age group rather than intervention group, and demonstrated significant age group differences in terms of sociodemographics, depression, and other comorbid medical illnesses. The intervention and comparison groups in all four studies seemed to have received similar treatment except for the intervention itself.

Turning to the next level of methodological quality we found two studies(48, 51) that utilized quasi-experimental designs comprised of open trials with sample sizes from 41 to 303. Information regarding blind-ratings was not provided. Although drop-out rates were reported (4% to 9.8%), the analysis of missing cases was not reported in one study(51) and drop-outs were not included in another(48). At baseline, statistically significant differences between experimental and comparison groups were found in one trial(51), although this was evident only among the non-Hispanic whites. Aside from the experimental intervention, the experiment and comparison groups seemed to be treated equally in both trials. However, the interventions delivered to Cohorts 1 and 2 in one study(48) varied by more than one variable.

The only study to use a pre-experimental design to assess change in depression without the use of a comparison group was the Healthy IDEAS study(49) which relied on case managers in existing community-based social service agencies. Based on 94 eligible participants, dropouts were not included in the analysis, and outcomes were not blind-rated.

Four of the studies took place largely in primary care, thus limiting the degree of generalization to non-specialty care settings where older people currently receive services, e.g., social service agencies, senior centers, adult day care, congregate and home delivered meal programs. There were no clear trends in drop-out rates by research design, presence of adaptations, or other measures examined across studies in this review.

Outcomes & Differential Response to Treatment

Favorable depression treatment effects were observed in samples comprised largely of older minorities in three randomized trials of collaborative or integrated care(45, 47, 50), in a quasi-experimental study of behavioral treatment in a rehabilitation hospital(48), and in a pre-experimental community case management program(49). Several caveats are worth noting. Although non-Hispanic whites were included in three of the studies reviewed(47–49), comparative analyses by race/ethnicity were not conducted and thus differential treatment response by race/ethnicity were not reported for these three studies. Among those who received group therapy in subsidized high-rise apartments(51), treatment effects were observed only among older non-Hispanic whites but not older minorities. Although access was improved across all racial/ethnic groups, significant clinical improvements in depression symptoms (e.g., statistically significant change in mean CES-D scores from baseline to 6-month follow-up) were not observed among older adults in the PRISM-E intervention compared to older adults in usual care, regardless of race or ethnicity(46).

Sociocultural Adaptations

Adaptations in each of the seven studies reviewed were reported by the original investigators in varying depth (see Table 3). As defined by Bernal et al.(41), the dimensions that best correspond to each study are listed. Two studies(46, 48) did not explicitly mention any adaptations that had been made to the intervention. One study(45) described adaptations corresponding to metaphors but solely through the portrayal of older adults from different minority backgrounds (i.e., representing cultural symbols) as actors in educational materials. Two studies(47, 49) described language adaptations through the use of bilingual providers and translated materials. Three interventions(47, 49, 51) were adapted by employing bilingual and/or racially matched personnel (persons). Adaptations targeting the methods in which the intervention was carried out were observed in two studies(50, 51). One study(51) described group sessions that opened with prayer reflecting the group’s common cultural and religious experiences, while another(50) identified cultural interviewing as the process by which the care manager worked with participants to develop culturally acceptable solutions to treatment non-adherence. The latter also exemplifies an adaptation addressing the intervention’s goals. Adaptations made to the content of the intervention were reflected in three studies(47, 50, 51) as these described cultural competency trainings, the use of culturally translated materials, and culturally competent evidence-based practices. Adaptations targeting the concepts, which refers to the constructs used within the intervention’s theoretical model, were observed in three studies(47, 50, 51). These demonstrate consonance between the participants’ culture and the manner that presenting problems are conceptualized by the researchers. None of the studies reported adaptations that addressed changing contexts (i.e., phases in migration, acculturative stress, availability of supports) often experienced by minority participants. Further, none of the studies tested the specific effect of the adaptations on treatment outcomes.

Table 3.

Cultural Considerations or Modifications Reported in Six Depression Treatment Studies

| Study/Year | Description of Modification | Treatment Dimensions* |

|---|---|---|

| Areán et al. /2005 | Older adults from different racial/ethnic backgrounds were depicted in case simulations in the educational video and written materials. | Metaphors (actors as ‘cultural symbols’) |

| Areán et al. /2008 | None reported. | N/A |

| Bogner & de Vries /2010 | Diabetes information was culturally tailored. Integrated care manager received training in cultural interviewing and sensitivity, and culturally competent evidence-based practices in order to establish rapport. Cultural interviewing was conducted by the integrated care manager to assist participants in developing culturally acceptable solutions to treatment non-adherence. | Methods Content Concepts Goals |

| Ell et al. /2010 | Three trials used bilingual (English/Spanish) providers and research staff; psychosocial therapy handouts and educational materials were translated linguistically and culturally; resource materials were also available in Spanish. Cultural competency training was provided to research staff. | Language Persons Content Concepts |

| Husaini et al./2004 | Five of the seven group leaders were African-American. Issues related to cultural sensitivity were raised during group therapy. In some groups, sessions opened with a prayer, initiated and led by group members, and reflecting common cultural and religious experiences. | Persons Methods Content Concepts |

| Lichtenberg /1997 | None reported. | N/A |

| Quijano et al. /2007 | The GDS-15 was professionally translated to Spanish and then reviewed by a focus group of bilingual service providers for content and meaning relevant to older Mexican-origin Latinos. Bilingual service workers implemented the intervention for older Latinos. | Language Persons |

Corresponding to criteria provided in Bernal, Bonilla, and Bellido(41)

CONCLUSIONS

Through an exhaustive systematic review process spanning published literature over 20 years, we analyzed seven studies reporting depression treatment outcomes for older minorities in the U.S. Several conclusions can be drawn albeit with caution given the small number of studies which met our criteria. First, the amount of evidentiary support of depression treatment among older minorities is slowly emerging since the seminal publication of the Surgeon General Report on Mental Health in 1999(8,34). Our search captured only seven published studies over a period of two decades. Had we applied stricter criteria so that the review included only the studies reporting treatment outcomes by minority group, then fewer studies would have been included.

Second, favorable depression treatment effects were observed for older minorities across five studies based on diverse settings and varying levels of sociocultural adaptations. With one exception(46), collaborative or integrated care models were found to be effective in reducing depression among older minorities, specifically with older Latinos and African Americans(45, 47, 50). The finding is based on a small number of studies, thus bringing into question just how generalizeable these results are for older minorities particularly those whom are limited English-speaking. Only one collaborative care study(47) reported to have offered treatment in additional languages. Moreover, the same study was the only one which drew primarily from safety net clinics that deliver a significant level of health care to uninsured, Medicaid, and socioeconomically impoverished patients. Thus, since we do not have sufficient information regarding representation of poverty- or near-poverty level subjects in the studies reviewed, there is some question whether these models address the unique needs of low acculturated, low-income, minority geriatric patients. Having said this, we cannot underestimate the care navigation processes inherent in collaborative and integrated care(23, 24) and outreach depression care models(25) that enhance access to resources that otherwise may not be attainable by older persons who typically confront fragmented behavioral health and long-term care systems.

Third, depression treatment effects remain largely unknown for some minority groups, especially older American Indian/Alaska Natives and to some extent Asian Americans. Furthermore, these ethnic groups are not homogeneous, as they include various distinct subgroups that differ in terms of culture, language, sociohistorical contexts, migration experience, and so forth. Although two studies(45, 49) described their sample of Latinos as primarily of Mexican origin, the remaining studies did not further characterize the national origin or descent of the racial/ethnic minority groups in their sample. Thus, depression treatment effects remain unknown for distinct racial/ethnic subgroups.

Fourth, the level of evidence for these interventions varied across studies and types of interventions. According to Rosenthal(55), the evidence accrued for evidence-based practices is highly dependent on the validity of the studies including research design or approach. Using validity criteria standards, we found greater support for collaborative care interventions for older minorities. This finding is consistent with the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which has identified the collaborative care models as an evidence-based practice for reducing depressive symptoms among older adults(56). There was less evidence of validity for the remaining studies largely due to their nonrandomized study designs and issues with attrition.

Fifth, we cast a wide net in terms of depression outcomes in our inclusion criteria which included both clinician-rendered depression diagnoses or symptomatology scales. Our ability to compare outcomes and evidence across studies was hampered by a variety of issues including differences in terms of diagnostic criteria, depression severity, and outcome measures. Only one study included a structured clinical interview which was not included as an outcome measure. Thus, the prominence of depressive symptomatology scales for both diagnostic and outcome criteria remains a challenge to this body of work. We did not intend to provide an exhaustive examination of the suitability of these measures for racial and ethnic groups which is an ongoing debate in the literature(57–59).

Sixth, it was not possible to decipher what specific component or combination of treatments may have worked best. With the exception of the Healthy IDEAS study(49) reporting that only the number of behavioral activation contacts predicted a significant change in depression scores, studies in this review did not report specific intervention component effects on outcomes. Therefore, it was not possible to disentangle the relative contribution of each treatment component. Moreover, this study(49) provides key insights into the portability of a depression intervention model utilizing non-graduate level practitioners to provide care to frail and culturally diverse older adults, an important factor for the development of the geriatric workforce.

Lastly, we discuss several points regarding sociocultural adaptations. Based on five studies(45, 47–50), we note that older minorities experience favorable treatment outcomes (across various depression measures) in interventions with varying degrees of reported sociocultural adaptations. However, we cannot discern whether these adaptations directly improved outcomes in comparison to a treatment arm that does not include the adaptation since these types of comparisons were not made in any of the studies reviewed. Theoretically, these adaptations should improve access and quality of care which translates to improved treatment utilization and adherence, other clinical outcomes, and satisfaction among the intended group or population(60). Our review highlights the difficulty with discerning the extent to which these adaptations contributed to favorable outcomes, or not. For example, one study noted that non-Hispanic whites fared better which was not the case for African Americans even within a socioculturally modified treatment protocol(51). Conversely, another study(48) did not report modifications yet favorable treatment outcomes were found in the sample comprised largely of African Americans. There were also challenges in differentiating the extent to which these adaptations contributed to favorable retention of participants in the interventions studied. Although trends in dropout rates were not found, we find it difficult to compare dropout information given the variability in treatment intensity and components, post-intervention observation points, and inconsistency of reporting dropout rates by racial/ethnic groups.

Furthermore, although the literature identifies that minorities may express and interpret psychological distress differently than non-Hispanic whites(36, 61, 62), the authors of the studies reviewed did not report or identify culturally-specific symptom presentation or syndromes. Beyond general statements regarding adaptations, we cannot discern the specific elements of translation, attention to culturally-specific issues, and the like, in order to ascertain what specifically was entailed in the modifications. For example, in one study(47), the investigators reported attention to cultural competency through the use of bilingual providers and research staff, cultural competency training, cultural and linguistic translation of the psychosocial therapy handouts and educational materials (p. 523). Although reported, the details of the “cultural translation” and the cultural competency training were not provided. In sum, the importance of sociocultural adaptations on depression outcomes in older minorities is emerging, yet the evidence supporting its effect is lacking.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. We included studies that reported outcomes for combined minority groups and non-Hispanic whites without conducting comparative analysis. Although we designated a threshold of >50% minorities in the sample when comparative analyses were lacking, this may restrict the degree of confidence that three of the studies(47–49) reported valid outcomes for older minorities. We nonetheless included these studies since the samples consisted largely of older minorities, and we feel that the results can be informative of the experience of older minorities. On the other hand, at the initial phases of the review process we captured several published articles that may have included an adequate sample size of minority older adults in number but did not meet our >50% minority threshold and/or did not meet our age limit criteria. These included five articles on the REACH-I or REACH-II caregiver intervention studies(63–67) that included older minority caregivers with depression. Although these studies did not make the final inclusion criteria, they nevertheless add to the scientific base on depression treatment and sociocultural adaptations in caregiving research. Likewise, studies such as PEARLS(25) did not make the final inclusion criteria, but are key outreach models with important real-life applications to depression care in community human service settings with minority representation. Furthermore, our rigorous set of criteria has the potential limitation of excluding studies on older adults that might have examined whether the treatment effect differed according to ethnicity, but finding none, do not report separate estimates of treatment effect for each minority group.

We included two studies that reported outcomes for samples that were not entirely age ≥60 (48, 51). These were included, as the authors branded their samples as geriatric or elderly. This may dilute our ability to say that these two studies are reflecting outcomes for older minorities, as not all research, policies, or services regard older adulthood to begin at age 50.

While culturally-specific symptom presentation and cultural-bound syndromes are relevant to the treatment of psychiatric disorders(61, 68), our literature review did not capture articles that reported these, specifically. However, this may well be a function of our inclusion criteria, as we focused on primary research on treatment for depression and our search terms for depression in each of the database indices may not have accommodated for culture bound syndromes.

We also found it difficult to decipher how adaptations were developed and how they mapped onto the dimensions of culturally sensitive treatment designated by Bernal and colleagues(41). Since the studies varied in terms of the depth of the description regarding adaptations, our interpretation of their adaptations (i.e., what they mean by cultural translation and/or culture-related issues) and the treatment dimensions that they addressed may not be truly reflective of their actual efforts which were minimally described. Our appraisal of the adaptations would have benefited from more detail on the processes that were implemented, but these details were not reported in the studies reviewed. Moreover, some interventions such as collaborative or integrated care models inherently address access barriers that are typical of minority populations as well as older adults. However, since this aspect of the intervention was not explicitly mentioned to have been developed or included for purposes of increasing cultural acceptability or accessibility per se, it was not counted as an adaptation.

Lastly, our review may be limited by the selection of databases utilized or not in the review, and by our criteria to target only published studies in peer-reviewed journals, which omitted unpublished work or studies in progress.

Conclusions on depression treatment among older minorities are currently limited to these seven studies and must be interpreted with caution. Given the high disease burden among older minorities with depression, it is important to increase the participation of older minorities in depression treatment research as well as increase the number of studies that report outcomes for older minority groups. Considering the rapid increase in racial and ethnic minority older adult populations and the projections of “the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health”(69), mental health research will need to access older minorities in significant numbers as a start to closing the mental health disparities chasm among this population within the next 20 years(9).

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant R21MH080624 (Dr. Aranda, PI). This paper is the result of work supported with resources from the Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging at the School of Social Work, University of Southern California (Ms. Fuentes).

Footnotes

This work was presented at the 64th Annual Scientific Meeting of The Gerontological Society of America, Boston MA, November 2011.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 4 Projections of the population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States: 2010 to 2050 (NP2008-T4) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 12 Projections of the population by age and sex for the United States: 2010 to 2050 (NP2008-T12) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: themes for the new century. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1158–1166. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, et al. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez DE, Alegría M, Chen C-n, et al. Prevalence of Psychiatric Illnesses in Older Ethnic Minority Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115–123. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffens DC, Fisher GG, Langa KM, et al. Prevalence of depression among older Americans: the Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:879–888. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman DP, Perry GS. Depression as a major component of public health for older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJL, et al. Assessing the Burden of Disease in the United States Using Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Pharmacotherapy of depression in older patients: a summary of the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7:361–376. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1419–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS. Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:558–567. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181693288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng XD, Huang CQ, Chen LJ, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and reminiscence techniques for the treatment of depression in the elderly: a systematic review. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:975–982. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson K, Mottram P, Sivanranthan A, et al. Antidepressant versus placebo for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD000561. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson K, Mottram P, Vassilas C. Psychotherapeutic treatments for older depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD004853. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004853.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scogin F. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Depression in Older Adults. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:222–237. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds CF., 3rd Paroxetine treatment of depression in late life. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37 (Suppl 1):123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arean PA, Perri MG, Nezu AM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of social problem-solving therapy and reminiscence therapy as treatments for depression in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:1003–1010. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. Jama. 1997;278:1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unutzer J. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ. Clinical presentations of major depression by African Americans and whites in primary medical care practice. J Affect Disord. 1996;41:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrido MM, Kane RL, Kaas M, et al. Use of Mental Health Care by Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Federal action agenda: First steps. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Transforming mental health care in America. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aisenberg E. Evidence-based practice in mental health care to ethnic minority communities: has its practice fallen short of its evidence? Soc Work. 2008;53:297–306. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernal G, Scharro-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7:328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Roche M, Christopher MS. Culture and Empirically Supported Treatments: On the Road to a Collision? Culture & Psychology. 2008;14:333–356. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long-standing problem. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:467–486. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000005484.26741.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohl M, Lesser I, Smith M. Clinical Presentations of Depression in African American and White Outpatients. Cult Divers Ment Health. 1997;3:279–284. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.3.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallo JJ, Cooper-Patrick L, Lesikar S. Depressive symptoms of whites and African Americans aged 60 years and older. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:P277–286. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.p277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asnaani A, Richey JA, Dimaite R, et al. A cross-ethnic comparison of lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:551–555. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ea169f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Culture and health-related schemas: A review and proposal for interdisciplinary integration. Health psychology. 1992;11:267-267–276. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.4.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, et al. Cultural Sensitivity and Adaptation in Family-Based Prevention Interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3:241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1993;270:2598–2601. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aranda AP, Morano C. Psychoeducational strategies for Latino caregivers. In: Cox CB, editor. Dementia and Social Work Practice: Research and Interventions. New York: Springer Publishing; 2007. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Interian A, Diaz-Martinez AM. Considerations for culturally competent cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression with hispanic patients. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:84–97. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arean PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care. 2005;43:381–390. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arean PA, Ayalon L, Jin C, et al. Integrated specialty mental health care among older minorities improves access but not outcomes: results of the PRISMe study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/gps.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ell K, Aranda MP, Xie B, et al. Collaborative depression treatment in older and younger adults with physical illness: Pooled comparative analysis of three randomized clinical trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:520–530. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichtenberg P. The DOUR project: A program of depression research in geriatric rehabilitation minority inpatients. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1997;42:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quijano LM, Stanley MA, Petersen NJ, et al. Healthy IDEAS: A depression intervention delivered by community-based case managers serving older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2007;26:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogner HR, de Vries HF. Integrating type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment among African Americans: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:284–292. doi: 10.1177/0145721709356115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Husaini BA, Cummings S, Kilbourne B, et al. Group therapy for depressed elderly women. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy. 2004;54:295–319. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.54.3.295.40340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krahn DD, Bartels SJ, Coakley E, et al. PRISM-E: Comparison of integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models in depression outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:946–953. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lichtenberg P, Kimbarow M, Morris P, et al. Behavioral treatment of depression in predominantly African-American medical patients. Clinical Gerontologist. 1996;17:15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levkoff SE, Chen H, Coakley E, et al. Design and sample characteristics of the PRISM-E multisite randomized trial to improve behavioral health care for the elderly. J Aging Health. 2004;16:3–27. doi: 10.1177/0898264303260390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenthal R. Overview of evidence-based practice. In: Roberts AR, Yeager KR, editors. Foundations of evidence-based social work practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2006. pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Substance Abuse and Mental HEalth Services Administration. National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Canino G, Alegria M. Psychiatric diagnosis - is it universal or relative to culture? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:237–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, et al. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mui AC, Burnette D, Chen LM. Cross-cultural assessment of geriatric depression: A review of the CES-D and the GDS. In: Skinner JH, Teresi JA, Holmes D, et al., editors. Multicultural measurement in older populations. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snowden LR, Masland M, Ma Y, et al. Strategies to improve minority access to public mental health services in California: Description and preliminary evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:225–235. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alegria M, McGuire T. Rethinking a universal framework in the psychiatric symptom-disorder relationship. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:257–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leong FTL, Lau ASL. Barriers to Providing Effective Mental Health Services to Asian Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3:201–214. doi: 10.1023/a:1013177014788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups - A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eisdorfer C, Czaja SJ, Loewenstein DA, et al. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. Gerontologist. 2003;43:521–531. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elliott AF, Burgio LD, Decoster J. Enhancing caregiver health: Findings from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health II intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW, Solano N, et al. Change in indices of distress among Latino and Anglo female caregivers of elderly relatives with dementia: Site-specific results from the REACH national collaborative study. Gerontologist. 2003;43:580–591. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gallagher-Thompson D, Gray HL, Dupart T, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive/behavioral small group intervention for reduction of depression and stress in non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino women dementia family caregivers: Outcomes and mediators of change. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2008;26:286–303. doi: 10.1007/s10942-008-0087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alarcon RD. Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnosis: review and projections. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:131–139. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: research agenda for the next 2 decades. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:848–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]