Abstract

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) single-node explants undergoing in vitro tuberization produced detectable amounts of ethylene throughout tuber development, and the resulting microtubers were completely dormant (endodormant) for at least 12 to 15 weeks. The rate of ethylene production by tuberizing explants was highest during the initial 2 weeks of in vitro culture and declined thereafter. Continuous exposure of developing microtubers to the noncompetitive ethylene antagonist AgNO3 via the culture medium resulted in a dose-dependent increase in precocious sprouting. The effect of AgNO3 on the premature loss of microtuber endodormancy was observed after 3 weeks of culture. Similarly, continuous exposure of developing microtubers to the competitive ethylene antagonist 2,5-norbornadiene (NBD) at concentrations of 2 mL/L (gas phase) or greater also resulted in a dose-dependent increase in premature sprouting. Exogenous ethylene reversed this response and inhibited the precocious sprouting of NBD-treated microtubers. NBD treatment was effective only when it was begun within 7 d of the start of in vitro explant culture. These results indicate that endogenous ethylene is essential for the full expression of potato microtuber endodormancy, and that its involvement may be restricted to the initial period of endodormancy development.

At harvest and for a finite period thereafter, potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers will not sprout and are in a state of dormancy (Burton, 1989). Because tuber dormancy results from factors arising within the affected organ itself and not from external causes (e.g. correlative inhibition or environmentally imposed quiescence), it is more properly classified as endodormancy (Lang et al., 1987). The duration of tuber endodormancy varies and is dependent on both the cultivar (i.e. genetic background) and, to some extent, the environmental conditions during tuber development (Burton, 1989). Within reasonable limits, postharvest environmental conditions have only a minimal effect on the length of endodormancy.

As with many aspects of plant development, plant hormones have been assigned a primary role in the regulation of potato tuber endodormancy (Rappaport and Wolf, 1969; Hemberg, 1985). Four of the five principal classes of plant hormones (ABA, cytokinins, GAs, and ethylene) have been implicated in dormancy regulation (Hemberg, 1985; Suttle, 1996a; Wiltshire and Cobb, 1996). In this paradigm, ABA is considered to be the principal dormancy-inducing agent, whereas both cytokinins and GAs are thought to regulate the termination of endodormancy. However, much of the experimental evidence supporting this theory is based on the pharmacological effects of exogenous growth regulators and on correlative studies comparing gross changes in endogenous tuber hormone levels with sprouting behavior. Therefore, much of the experimental evidence is equivocal and subject to justifiable criticism (Suttle, 1996a). Only recently has the involvement of endogenous ABA been unequivocally demonstrated (Suttle and Hultstrand, 1994). At present the roles of the remaining hormones are speculative (Suttle, 1996a).

The involvement of endogenous ethylene in tuber endodormancy regulation, in particular, is uncertain. Rosa (1925) was the first to report an effect of ethylene on shortening the natural period of potato tuber dormancy. Subsequent studies by Denny (1926a, 1926b) failed to corroborate these findings. More recently, exogenous ethylene (or ethylene-releasing agents) have been reported to elicit seemingly contradictory responses. Depending on the concentration and duration of exposure, exogenous ethylene can either hasten or delay tuber sprouting. Relatively short-term (less than 3 d) exposure to ethylene results in the premature termination of tuber endodormancy, whereas long-term or continuous exposure to similar concentrations of ethylene inhibits subsequent sprout growth (Rylski et al., 1974). Temporary treatment with exogenous ethylene has also been reported to stimulate the sprouting of partially dormant tubers (Alam et al., 1994).

Similarly, application of an ethylene-releasing agent, alone or in combination with GA3, to dormant tubers has been reported to stimulate sprouting (Shashirekha and Narasimham, 1988). Conversely, it has been reported that both preharvest and postharvest applications of the ethylene-releasing agent ethephon resulted in significant extensions of tuber dormancy (Korableva et al., 1989; Cvikrova et al., 1994). Therefore, it is clear that the role, if any, of ethylene in potato tuber endodormancy regulation is uncertain at best.

In light of these uncertainties, and as a continuation of ongoing research examining the role(s) of endogenous hormones in potato tuber endodormancy regulation, the involvement of endogenous ethylene in the induction and maintenance of tuber endodormancy has been critically evaluated using an aseptic in vitro tuberization system and specific inhibitors of ethylene action. Portions of this research have appeared previously in abstract form (Suttle, 1996b).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Experimental Procedures

Clonally propagated potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv Russet Burbank) plantlets were aseptically grown using in vitro culture methods, as described previously (Suttle and Hultstrand, 1994). Plantlets were cultured in 15-cm × 22-mm tubes containing 10 mL of Murashige and Skoog basal salts and vitamins (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 3% (w/v) Suc and 0.6% (w/v) Phytagel (Sigma1). The pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8 before the addition of Phytagel. Plantlets were grown under fluorescent lights (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at room temperature. Plantlets were subcultured or used for experimentation after 4 to 6 weeks of growth. Sprouting was assessed visually according to established guidelines (Reust, 1986). A microtuber was considered sprouted if it had any sprouts ≥ 2 mm in length. All experiments described in this paper were conducted a minimum of two times. Individual treatments within an experiment were replicated (n = 3). Data from representative experiments are shown.

Microtuber Induction

Single-node explants (including the leaf) were excised from the lower one-third of each plantlet. Groups of 10 explants were subcultured in Phytatrays (Sigma) that contained approximately 100 mL of Murashige and Skoog basal salts supplemented with a vitamin mixture (Nitsch and Nitsch, 1969), 10 mg/L kinetin, 0.1 mg/L IAA, 8% (w/v) Suc, any test compounds, and 0.6% (w/v) agar. Silver nitrate was added from a 0.1 m aqueous stock solution. The pH was adjusted to 5.7 before autoclaving. Explants were incubated in the dark (18°C ± 1°C), and the progress of tuberization and sprouting were monitored thereafter.

Ethylene Determinations

At the indicated times during culture, groups of three explants were aseptically transferred to sterile tubes (22 mm × 10.5 cm) that contained a plug of sterile cotton gauze. The tubes were sealed with serum caps and incubated in the dark at 18°C ± 1°C. After 16 h, a 1-mL sample was withdrawn and the ethylene content was determined by GC using an alumina column. The explants were then aseptically returned to their original container for further observation.

NBD Treatments

Treatments with NBD were conducted in 4.5-L Plexiglas containers. Each treatment consisted of three Phytatrays each containing 10 explants. For the NBD dose-response studies and the ethylene-reversal studies, the treatments were initiated the day after the start of in vitro culture. For the time-course studies, NBD treatments were initiated at the indicated times after the start of in vitro culture. In all cases, the Plexiglas chambers were opened every 7 d, vented to the atmosphere, resealed, and fresh NBD (with or without ethylene) was reintroduced. The chambers were incubated in the dark at 18°C ± 1°C. NBD was added as a liquid immediately before sealing each chamber. NBD concentrations (gas phase) were calculated from the amount of liquid added and the chamber volume.

RESULTS

Under the in vitro conditions used in this study, explant axillary growth began within 1 week of excision and culture. Subapical swelling (the initial stage of tuberization) was visible after 10 d of culture and, typically, microtubers with diameters of 2 mm or more had formed by 14 d of culture. The microtubers continued to grow; reaching a final diameter of approximately 5 to 7 mm and a final fresh weight of approximately 150 to 300 mg each. Under these conditions, greater than 90% of the explants produced microtubers. Microtubers remained dormant for a minimum of 12 to 15 weeks after initiation.

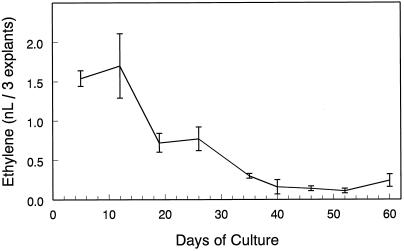

The rates of ethylene production in freshly excised, single-node explants undergoing tuberization were examined after various periods of in vitro culture. Explants produced low but detectable amounts of ethylene during the entire period of culture (Fig. 1). The rates of ethylene production were highest during the initial period of culture, declined to an intermediate level by d 20, remained stable for roughly 1 week, declined further until d 40, and remained stable thereafter. Because of the effects of excision and subsequent handling on wound ethylene production, no attempt was made to determine the rates of ethylene production before 5 d of culture.

Figure 1.

Changes in the rate of ethylene production by single-node explants during in vitro culture. Groups of three explants were aseptically removed from the culture vessels, incubated overnight at 18°C ± 1°C in sealed tubes, and the accumulated ethylene was determined by GC. Bars indicate ±se (n = 3).

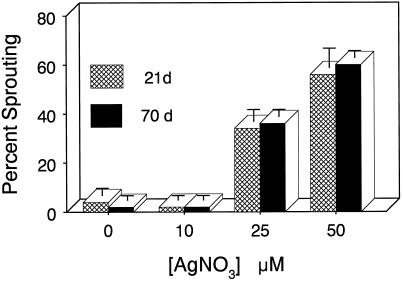

The possible involvement of endogenously produced ethylene was examined next through the use of two inhibitors of ethylene action. Continuous exposure of developing explants to the noncompetitive ethylene antagonist AgNO3 (Veen, 1987) resulted in a dose-dependent increase in premature microtuber sprouting (Fig. 2). At concentrations of 10 μm or less, AgNO3 was ineffective. Ten weeks after initiation, microtubers formed in the presence of 25 μm AgNO3 exhibited 36% sprouting, whereas those exposed to 50 μm exhibited 60% sprouting. The effects of AgNO3 appeared rapidly and were essentially complete within 3 weeks of in vitro culture. As judged by tuberization, no signs of phytotoxicity were observed at any treatment concentration, and explants exposed to 50 μm AgNO3 exhibited 98% tuberization (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of increasing concentrations of AgNO3 on microtuber sprouting percentage. Groups of 10 explants were exposed to AgNO3 via the culture medium. Sprouting percentage was determined after 3 (hatched bars) and 10 (solid bars) weeks of culture. Bars indicate ±se (n = 3).

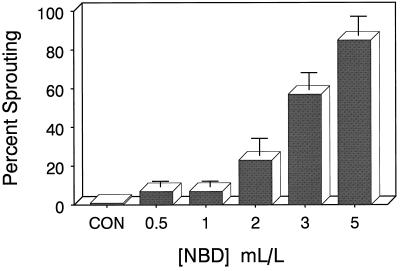

Continuous exposure to the competitive ethylene antagonist NBD (Sisler, 1991) at concentrations of 2 mL/L (gas phase) or greater also resulted in a dose-dependent increase in premature microtuber sprouting (Fig. 3). The extent of premature sprouting continued to increase as the concentration of NBD was increased to 5 mL/L, reaching a value of 85%. Higher concentrations of NBD were not tested. As before, no signs of phytotoxicity were noted at any treatment level, and the extent of tuberization exceeded 90% at the highest dose used (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of increasing concentrations of NBD on microtuber sprouting percentage. On the day after excision and transplanting, three groups of 10 explants were sealed in Plexiglas chambers (4.5 L) containing the indicated concentrations of NBD. The chambers were incubated in the dark at 18°C ± 1°C, and the sprouting percentage was determined after 10 weeks of culture. Bars indicate ±se (n = 3).

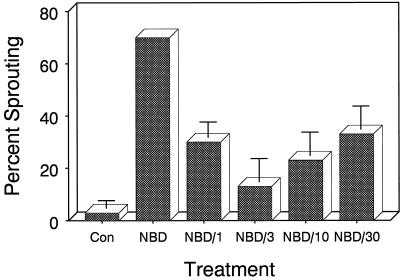

The specificity of this response was examined by determining the ability of exogenous ethylene to reverse the effect of NBD and to prevent premature sprouting. Developing microtubers were continuously exposed to 3 mL/L NBD in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of exogenous ethylene. Control tubers (no treatment) exhibited only limited (3%) sprouting after 10 weeks of culture (Fig. 4). Continuous exposure to NBD resulted in 70% sprouting. Inclusion of exogenous ethylene at concentrations between 1 and 30 μL/L together with NBD largely reversed the response and prevented premature microtuber sprouting. At this NBD treatment level, an ethylene concentration of 3 μL/L was optimum, reducing premature sprouting from 70% to 13%. Ethylene concentrations less than 1 μL/L were not tested, and concentrations greater than 30 μL/L resulted in severe morphological abnormalities in the developing microtubers (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of increasing concentrations of ethylene on sprouting percentage in NBD-treated explants. On the day after excision and transplanting, three groups of 10 explants were sealed in Plexiglas chambers (4.5 L) containing 3 mL/L NBD in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations (microliters per liter) of ethylene. Con, Controls (explants sealed in chambers receiving no treatment). The chambers were incubated in the dark at 18°C ± 1°C, and the sprouting percentage was determined after 10 weeks of culture. Bars indicate ±se (n = 3).

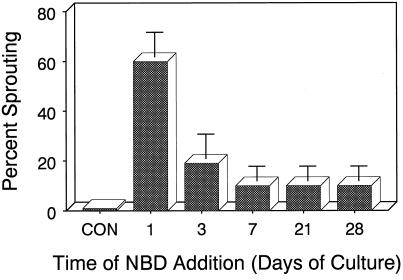

Because of its efficacy and ease of application, NBD treatment was used to determine the temporal pattern of ethylene action with respect to dormancy control in developing microtubers. After 10 weeks of culture, untreated (control) microtubers had not sprouted and were completely dormant (Fig. 5). Microtubers continuously exposed to 3 mL/L NBD beginning on the 1st d of in vitro culture exhibited 60% sprouting after 10 weeks. However, NBD rapidly lost its effectiveness. Application of NBD more than 7 d after the start of in vitro culture elicited little effect, and these microtubers remained dormant, exhibiting only 10% sprouting after 10 weeks of culture. These results suggest that with respect to dormancy regulation, ethylene action is only required during the very earliest period of tuber development and is not needed thereafter.

Figure 5.

Effects of culture age on NBD-induced precocious sprouting. On the day after excision and transplanting, explants were incubated in sealed Plexiglas chambers (4.5 L) in the dark at 18°C ± 1°C. At the indicated times after the initiation of in vitro culture, three groups of 10 explants were exposed to NBD (3 mL/L). Con, Controls (explants sealed in chambers receiving no treatment). Sprouting percentage was determined after 10 weeks of culture. Bars indicate ±se (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Endogenous ethylene is known to participate in the regulation of many diverse aspects of plant development, from seed germination through organ senescence and death (Reid, 1995). The results presented in this manuscript describe a previously unrecognized role for endogenous ethylene in the regulation of potato tuber bud (eye) endodormancy. Experimental evidence supporting this role include: (a) single-node potato explants undergoing tuberization produce ethylene throughout the period of microtuber development (Fig. 1); (b) inhibition of ethylene action with the noncompetitive antagonist AgNO3 (Fig. 2) or the competitive antagonist NBD (Fig. 3) inhibits the full expression of bud endodormancy and promotes premature sprouting; and (c) exogenous ethylene reverses the action of NBD and inhibits premature sprouting (Fig. 4). Attempts to prevent ethylene action by inhibiting its synthesis with aminoethoxyvinylglycine were only partially successful, possibly owing to the incomplete inhibition of ethylene biosynthesis that was typically observed after aminoethoxyvinylglycine exposure via the culture medium (data not shown).

The hypothesis that tuber volatiles are involved in sprout growth regulation is not new. Burton (1952) demonstrated that dormant tubers produce volatile compounds capable of inhibiting sprout growth. Subsequent studies identified a number of bioactive compounds in the volatile fraction, including benzothiazole, diphenylamine, and 1,4- and 1,6-dimethylnaphthalene (Meigh et al., 1973). Although ethylene was also identified as a component of the volatile fraction, its involvement in volatile-induced sprout growth inhibition was discounted because of its very low concentration in the total volatile fraction and its relatively poor bioactivity (Burton and Meigh, 1971; Rylski et al., 1974). Given the low rates of ethylene evolution and the ephemeral nature of the ethylene requirement, it is likely that without the use of the in vitro tuberization system and the specific inhibitors of ethylene action, the role of endogenous ethylene in potato tuber dormancy regulation would have again escaped detection.

Tuber dormancy can be divided into three phases: induction, maintenance, and termination. At present, it is unclear if or to what extent the physiological mechanisms regulating each of these stages overlap. The observed rapid (within 7 d) loss of NBD efficacy during tuber development (Fig. 5) indicates that endogenous ethylene is required only during the earliest or induction phase of tuber endodormancy. This conclusion is also supported by the rapid response of explants to AgNO3 treatment (Fig. 2). In this case, premature sprouting was observed after 3 weeks of culture or immediately after tuber initiation. It is during this same period that explants with developing microtubers exhibit the highest rates of ethylene production (Fig. 1). This temporal pattern of action is different from that of ABA (Suttle and Hultstrand, 1994) and suggests distinct roles for each in endodormancy regulation.

The period of ethylene sensitivity corresponded with the period of subapical swelling (the first detectable sign of tuberization). It has been suggested that the initiation of both tuberization and dormancy occur simultaneously (Burton, 1989). With the exception of premature sprouting, NBD-treated microtubers were indistinguishable from their untreated counterparts after 10 weeks of culture, and the extent of explant tuberization was identical (>90%) in both groups. These observations indicate that, although they are temporally related, the processes of tuberization and dormancy induction are experimentally separable and are therefore physiologically distinct. A similar situation was observed in ABA-deficient microtubers (Suttle and Hultstrand, 1994).

Because ethylene evolution was determined using explants that contained leaf tissue, stem tissue, and a developing microtuber, the exact source of the ethylene produced is not known. In general, intact and undamaged potato tubers exhibit very low rates of ethylene production (Rylski et al., 1974; Gude and van der Plas, 1985). However, as with many other plant tissues, the rate of ethylene production increases dramatically after wounding, pathogen exposure, or treatment with various xenobiotics (Creech et al., 1973; Okazawa, 1974; Gude and van der Plas, 1985). The physiological/biochemical processes that regulate ethylene production in potato tuber tissues have received only limited attention and are poorly understood.

The studies described in this report concern the production and action of endogenous ethylene during the earliest period of tuber development and dormancy initiation. It was reported previously that the rate of ethylene production exhibited a transient increase in mature, freshly harvested, field-grown potatoes, and this was taken as an indication of the involvement of ethylene in the inception of tuber dormancy (Cvikrova, et al., 1994). The possible relevance of these studies to the results presented here is difficult to assess. First, potatoes are fully dormant at the time of harvest and, as stated earlier, it is generally believed that tuber dormancy begins either at the time of tuberization or shortly thereafter (Burton, 1989). Second, it is possible that the observed transient increase in ethylene production by these mature tubers was a result of the unavoidable tuber damage and tissue trauma associated with harvesting. Therefore, although the conclusions of this earlier study are in agreement with those presented here, the relevance of these earlier observations with respect to this study and to endodormancy control in potatoes in general remains to be established.

Potato tuber endodormancy was initially hypothesized to result from an excess of inhibitors, and later by a balance between inhibitors and promoters (Hemberg, 1985), and theories concerning its regulation have continued to evolve and become more complex as new experimental evidence is gathered (Coleman, 1987; Suttle, 1996a; Wiltshire and Cobb, 1996). Classic and more recent genetic studies have confirmed the polygenic nature of tuber dormancy (Freyre et al., 1994; Van den Berg et al., 1996). These studies, together with more recent physiological studies, illustrate the rich complexity in the regulation of this important phase of plant development, and indicate that our understanding of this phenomenon is rudimentary at best. The discovery of a role for endogenous ethylene in tuber endodormancy was unexpected and would not have been predicted from its involvement in other forms of dormancy. Future studies will no doubt identify still other endogenous factors that affect this process.

In summary, the results presented in this paper demonstrate that endogenous ethylene plays an essential role in the regulation of potato microtuber endodormancy. Although these results establish an essential role for ethylene, the nature of this role is unknown. Previous results from this laboratory have demonstrated that the sustained synthesis and action of ABA are essential for the establishment and maintenance of microtuber endodormancy (Suttle and Hultstrand, 1994). Both ABA and ethylene interact in the regulation of other physiological processes, including the expression of certain wound-induced genes and the regulation of leaf abscission (Hildmann et al., 1992; Suttle and Hultstrand, 1993; O'Donnell et al., 1996). The nature and extent of the interaction of ABA and ethylene in tuber endodormancy regulation is unknown. It is possible that the actions of ethylene and ABA are mutually interdependent, with the effects of one mediated by the other. Alternatively, ABA and ethylene could act independently, with the combined actions of both being required for the successful development of tuber endodormancy. These possibilities are currently under investigation.

Abbreviation:

- NBD

2,5-norbornadiene

Footnotes

Mention of a trademark or proprietary product does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products that may also be suitable.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alam SMM, Murr DP, Kristof L. The effect of ethylene and of inhibitors of protein and nucleic acid syntheses on dormancy break and subsequent sprout growth. Potato Res. 1994;37:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Burton WG. Studies on the dormancy and sprouting of potatoes. III. The effect upon sprouting of volatile metabolic products other than carbon dioxide. New Phytol. 1952;51:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burton WG (1989) The Potato, Ed 3. Longman Scientific & Technical, Essex, UK, pp 470–504

- Burton WG, Meigh DF. The production of growth-suppressing volatile substances by stored potato tubers. Potato Res. 1971;14:96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman WK. Dormancy release in potato tubers: a review. Am Potato J. 1987;64:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Creech DL, Workman M, Harrison MD. Influence of storage factors on endogenous ethylene production by potato tubers. Am Potato J. 1973;50:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cvikrova M, Sukhova LS, Eder J, Korableva NP. Possible involvement of abscisic acid, ethylene and phenolic acids in potato tuber dormancy. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1994;32:685–691. [Google Scholar]

- Denny FE. Hastening the sprouting of dormant potato tubers. Am J Bot. 1926a;13:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Denny FE. Second report on use of chemicals for hastening the sprouting of dormant potato tubers. Am J Bot. 1926b;13:386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Freyre R, Warnke S, Sosinski B, Douches DS. Quantitative trait locus analysis of tuber dormancy in diploid potato (Solanum spp.) Theor Appl Genet. 1994;89:474–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00225383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gude H, van der Plas LHW. Endogenous ethylene formation and the development of the alternate pathway in potato tuber disks. Physiol Plant. 1985;65:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg T. Potato rest. In: Li PH, editor. Potato Physiology. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 354–388. [Google Scholar]

- Hildmann T, Ebneth M, Pena-Cortes H, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Willmitzer L. General roles of abscisic acid and jasmonic acids in gene activation as a result of mechanical wounding. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1157–1170. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.9.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korableva NP, Sukhova LS, Dogonadze MZ, Machackova I (1989) Hormonal regulation of potato tuber dormancy and resistance to pathogens. In J Kredule, R Seidlova, eds, Signals in Plant Development. SPB Academic Publishers, The Hague, pp 65–71

- Lang GA, Early JD, Martin GC, Darnell RL. Endo-, para-, and ecodormancy: physiological terminology and classification for dormancy research. HortScience. 1987;22:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Meigh DF, Filmer AAE, Self R. Growth-inhibitory volatile aromatic compounds produced by Solanum tuberosum tubers. Phytochemistry. 1973;12:987–993. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473. [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch JP, Nitsch C. Haploid plants from pollen grains. Science. 1969;163:85–87. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3862.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell PJ, Calvert C, Atzorn R, Wasternack C, Leyser HMO, Bowles DJ. Ethylene as a signal mediating the wound response of tomato plants. Science. 1996;274:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazawa Y. A relation between ethylene evolution and sprouting of potato tuber. J Fac Agric Hokkaido Univ. 1974;57:443–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport L, Wolf N. The problem of dormancy in potato tubers and related structures. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1969;23:219–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS. Ethylene in plant growth, development, and senescence. In: Davies PJ, editor. Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Ed 2. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 486–508. [Google Scholar]

- Reust W. EAPR Working Group: physiological age of the potato. Potato Res. 1986;29:268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa JT (1925) Shortening the rest period of potatoes with ethylene gas. Potato Association of America, Potato News Bulletin 2: 363–365

- Rylski I, Rappaport L, Pratt HK. Dual effects of ethylene on potato dormancy and sprout growth. Plant Physiol. 1974;53:658–662. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashirekha MN, Narasimham P. Comparative efficacies of gibberellic acid (GA) and ethrel mixture and other established chemicals for the induction of sprouting in seed potato tubers. J Food Sci Technol. 1988;25:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Sisler EC. Ethylene-binding components in plants. In: Mattoo AK, Suttle JC, editors. The Plant Hormone Ethylene. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Suttle JC (1996a) Dormancy in tuberous organs: problems and perspectives. In GA Lang, ed, Plant Dormancy: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 133–143

- Suttle JC. Role of ethylene in potato microtuber dormancy (abstract no. 478) Plant Physiol. 1996b;111:S-116. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle JC, Hultstrand JF. Involvement of abscisic acid in ethylene-induced cotyledon abscission in cotton seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:641–646. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.2.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle JC, Hultstrand JF. Role of endogenous abscisic acid in potato microtuber dormancy. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:891–896. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg JH, Ewing EE, Plaisted RL, McMurry S, Bonierbale MW. QTL analysis of potato tuber dormancy. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93:317–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00223171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veen H. Use of inhibitors of ethylene action. Acta Hortic. 1987;201:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire JJJ, Cobb AH. A review of the physiology of potato tuber dormancy. Ann Appl Biol. 1996;129:553–569. [Google Scholar]