Summary

Birth-date-dependent neuronal layering is fundamental to neocortical functions. The extracellular protein Reelin is essential for the establishment of the eventual neuronal alignments. Although this Reelin-dependent neuronal layering is mainly established by the final neuronal migration step called “terminal translocation” beneath the marginal zone (MZ), the molecular mechanism underlying the control by Reelin of terminal translocation and layer formation is largely unknown. Here, we show that after Reelin binds to its receptors, it activates integrin α5β1 through the intracellular Dab1-Crk/CrkL-C3G-Rap1 pathway. This intracellular pathway is required for terminal translocation and the activation of Reelin signaling promotes neuronal adhesion to fibronectin through integrin α5β1. Since fibronectin is localized in the MZ, the activated integrin α5β1 then controls terminal translocation, which mediates proper neuronal alignments in the mature cortex. These data indicate that Reelin-dependent activation of neuronal adhesion to the extracellular matrix is crucial for the eventual birth-date-dependent layeringof the neocortex.

Introduction

The mammalian neocortex has a highly organized 6-layered structure of neurons, which serves as the fundamental basis of higher brain functions (Rakic, 2009). This layered cortical structure is composed of a birth-date-dependent “inside-out” alignment of the projection neurons; late-born neurons are located more superficially than the early-born neurons. Neuronal migration plays essential roles in the establishment of this expanding laminar structure, and one of the prominent features is the sequential and complex changes of the migratory modes of the neurons that allows the later-born neurons to migrate beyond the already settled predecessors (Ayala et al., 2007) (Marin et al., 2010). After the final cell division in the ventricular zone (VZ) or subventricular zone (SVZ), projection neurons begin to show multipolar migration just above the ventricular zone (VZ) or in the multipolar cell accumulation zone (MAZ) (Tabata and Nakajima, 2003) (Tabata et al., 2009). They then transform into bipolar cells with one leading process and migrate long distances through the intermediate zone (IMZ) and cortical plate (CP) along the radial glial fibers (the “locomotion” mode) (Rakic, 1972) (Nadarajah et al., 2001). Finally, beneath the outermost region of the CP, the migrating neurons switch to the “terminal translocation” mode, in which their somas move quickly in a radial-glia-independent manner, while the tips of the leading processes retain their attachment to the marginal zone (MZ), and complete their migration to just beneath the MZ (Nadarajah et al., 2001).

Reelin is an extracellular matrix (ECM) protein secreted from the Cajal-Retzius cells in the MZ (D’Arcangelo et al., 1995) (Ogawa et al., 1995). It is essential for the establishment of the birth-date-dependent layered structure of the neocortex, because Reelin-signaling deficient mice show roughly inverted cortical layers (Rice and Curran, 2001). However, how Reelin controls layer formation in vivo is not fully understood.

Recent studies suggested that Reelin signaling regulates the terminal translocation mode of neuronal migration near the outermost region of the CP (Olson et al., 2006) (Franco et al., 2011) (Sekine et al., 2011). We recently found that this outermost region of the CP is densely packed with NeuN-negative immature neurons and possesses unique features distinct from the rest of the CP, and named this region the primitive cortical zone (PCZ) (Sekine et al., 2011). Importantly, terminal translocation during development is essentially required for proper establishment of the eventual pattern of neuronal alignment in the mature cortex (Franco et al., 2011), and this birth-date-dependent neuronal alignment is mainly established within the PCZ through terminal translocation (Sekine et al., 2011). Therefore, to elucidate how Reelin signaling regulates terminal translocation is critical to understand the mechanism of the neocortical layer formation.

Reelin binds to its receptors, Apo-lipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and Very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR), and induces the phosphorylation of the intracellular adaptor protein Disabled homolog 1 (Dab1) in migrating neurons (D’Arcangelo et al., 1999) (Hiesberger et al., 1999) (Trommsdorff et al., 1999) (Rice and Curran, 2001). It was also reported that Reelin could bind to an integrin receptor (Dulabon et al., 2000), although the effects of this interaction for neuronal migration is controversial (Magdaleno and Curran, 2001). In this study, we show that after Reelin binds to ApoER2/VLDLR, it activates integrin α5β1 on the migrating neurons through the intracellular Dab1-Crk/CrkL-C3G-Rap1 pathway (“inside-out” activation of integrin (Kinashi, 2005) (Shattil et al., 2010)), which promotes neuronal adhesion to fibronectin. Since fibronectin is present in the MZ, activated integrin α5β1 (a fibronectin receptor) then mediates terminal translocation through the PCZ. Furthermore, sequential in utero electroporation studies show that this integrin activation is indeed required for proper establishment of the eventual neuronal positioning in the mature cortex in vivo. Interestingly, whereas the Rap1-N-cadherin pathway is involved in the migration below the CP (Jossin and Cooper, 2011), we found that it could not promote neuronal entry into the PCZ by terminal translocation, suggesting that Rap1 has dual functions during different phases of neuronal migration and that Reelin changes the downstream adhesion molecules of Rap1 during terminal translocation. Our data suggest that Reelin-dependent modulation of neuronal adhesion is critical for the eventual birth-date-dependent neuronal layering in the neocortex.

Results

Tyrosine 220/232 phosphorylation of Dab1, Crk/CrkL adaptors, and C3G are required for terminal translocation

Several studies have reported that Dab1 is required for terminal translocation, which is necessary for the establishment of the birth-date-dependent “inside-out” neuronal layering (Olson et al., 2006) (Cooper, 2008) (Franco et al., 2011) (Sekine et al., 2011). Since Dab1 is a multifunctional adaptor protein that can selectively recruit several downstream molecules to its specific phosphorylation sites (Honda et al., 2011), we first analyzed the effects of Dab1 phosphorylation on terminal translocation using various tyrosine mutants of Dab1. When a Dab1-knockdown (KD) vector was introduced into the mouse embryonic neocortex by in utero electroporation at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), the transfected cells were mislocated just beneath the NeuN-negative region of the CP or the PCZ (Sekine et al., 2011) on postnatal day 0.5 (P0.5), 5 days after the electroporation (Figure 1A–B′), suggesting that terminal translocation was disrupted. This Dab1-KD phenotype was rescued by co-transfection of the cells with wild-type Dab1 (Figure S1A, B). Dab1 has 5 potential tyrosine residues phosphorylated by Reelin (tyrosines 185, 198, 200, 220, and 232), and Dab1-5F, lacking all these tyrosine residues, Dab1-3F, lacking the three main phosphorylation sites (198F, 220F, and 232F) (Keshvara et al., 2001), and Dab1-220F/232F could not rescue the Dab1-KD phenotype (Figure S1A, B), whereas all the single tyrosine mutants and the other double mutants could rescue the Dab1-KD phenotype, suggesting that phosphorylation of either tyrosine 220 or 232 of Dab1 is required for terminal translocation.

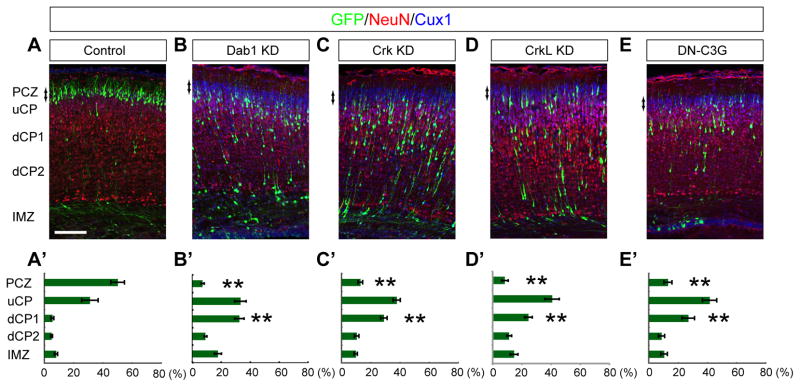

Figure 1. Involvement of the Dab1-Crk/CrkL-C3G pathway in terminal translocation.

Cerebral cortices at P0.5 electroporated with the indicated plasmids plus pCAGGS-EGFP at E14.5 (A–E). Red denotes NeuN-positive neurons. Blue denotes Cux1-positive upper CP (uCP: layer II–IV) neurons. PCZ denotes the NeuN-negative region (arrows). Layer V and VI neurons are equally divided into deep CP 1 (dCP1) and dCP2. (A′–E′) Graphs show the estimation of cell migration. Note that all of Dab1-KD, Crk-KD, CrkL-KD and DN-C3G affected the neuronal entry into the PCZ. n=5–7 brains. ** p<0.01. Scale bars, 100 μm. See also Figure S1.

Two kinds of adaptors, Crk/CrkL and Nckβ, can specifically bind to the phosphorylated tyrosines 220 and 232 of Dab1 (Park and Curran, 2008) (Honda et al., 2011). Using in utero electroporation of each KD vector (Figure S1C, E, I), we found that KD of either Crk or CrkL affected neuronal migration, including terminal translocation, whereas KD of Nckβ had no more than a slight effect on neuronal migration (Figure 1C–D′, Figure S1D, F). The phenotypes of Crk KD and those of CrkL KD were rescued by co-transfection of the respective non-targetable cDNAs (Figure S1G, H). In addition, many Crk KD cells were stalled in the middle of the upper CP, whereas many CrkL KD cells were positioned beneath the PCZ (Figure S1F, F′). The difference between these phenotypes seems to be consistent with a previous report showing that while both Crk and CrkL were also strongly expressed in the IMZ, CrkL was more strongly expressed in the superficial part of the CP (Park and Curran, 2008). Although single knock-out mice of either Crk or CrkL did not show any phenotype (Park and Curran, 2008), it is possible that the two closely related genes may have compensated with each other in the knock-out mice. Therefore, although we cannot fully exclude the possibility that our knockdown vectors may have some additional off-target effects because of the partial rescue results, our acute knockdown approach suggests that Crk has some slightly distinct roles from CrkL in neuronal migration.

Furthermore, C3G, a Rap1 activator or GEF (Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factor), can bind to Crk/CrkL and is activated by Reelin (Ballif et al., 2004). The dominant-negative (DN) form of C3G disrupted neuronal entry into the PCZ, just like Dab1-KD (Figure 1E, E′). Because Crk/CrkL and C3G are also involved in layer formation (Park and Curran, 2008) (Voss et al., 2008), these data suggest that the Crk/CrkL-C3G-dependent terminal translocation is also important for proper layer formation.

The Rap1/N-cadherin pathway regulates neuronal entry into the CP, but not into the PCZ

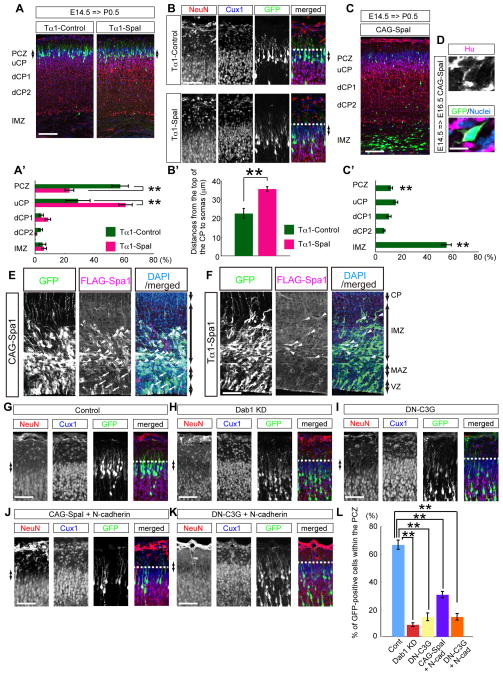

Two closely related C3G effectors, Rap1a and Rap1b, are strongly expressed in the developing CP as well as in the VZ at E16.5 (Figure S2A), suggesting the several functions of Rap1 for corticogenesis (Bos, 2005). To block the functions of both Rap1a and Rap1b in migrating neurons, we next introduced Spa1, the Rap1-GAP (GTPase-Activating Protein) (Tsukamoto et al., 1999) by in utero electroporation. When we introduced Spa1 under the control of a Tα1 promoter, which is moderately expressed in neurons (Gloster et al., 1994) and in a certain population of neuronal progenitors, but not in the radial glial cells (Gal et al., 2006), the labeled cells could not enter the PCZ, suggesting the failure of terminal translocation (Figure 2A–B′). Interestingly, however, when we overexpressed Spa1 under the control of a strong CAG promoter, many cells remained stalled in the lower part of the IMZ, unlike Dab1-KD or DN-C3G (Figure 2C, C′, Figure S2H, I). Expression of Tα1-Spa1 was detectable in the cells in the IMZ, whereas that of CAG-Spa1 was observed even in the VZ (Figure 2E, F). The effects of CAG-Spa1 were significantly rescued by the co-transfection of Rap1a, suggesting that Rap1 is the main physiological substrate of Spa1 during neuronal migration (Figure S2E). The ratio of bipolar cells in the IMZ was significantly decreased in the CAG-Spa1-overexpressed cells without affecting the neuronal differentiation (Figure 2D, Figure S2B–D, F, G), suggesting the failure of switching of the migratory mode from multipolar migration to locomotion, consistent with a previous report (Jossin and Cooper, 2011). Thus, these data suggest that Rap1 has dual functions for neuronal migration; one in the early phase below the CP and the other in the final phase of migration in the PCZ. In addition, because moderate expression of Spa1 under Tα1 promoter did not affect the neuronal migration in the IMZ, our data suggest that terminal translocation is more dependent on the Rap1 function than the neuronal migration in the IMZ.

Figure 2. Rap1 has dual functions for neuronal migration, and the Rap1/N-cadherin pathway is not sufficient for the neuronal entry into the PCZ.

Cerebral cortices at P0.5 (A–C) and at E16.5 (D) electroporated at E14.5. Note that Tα1-Spa1 affected the neuronal entry into the PCZ (arrows) whereas CAG-Spa1 affected the neuronal entry into the CP. (A′, C′) Graphs show the estimation of cell migration. (B′) Statistical analyses of terminal translocation failure of (B). GFP-positive cells within the uCP were counted. **, p=0.00194. n=6 (control), n=8 (Tα1-Spa1), and n=7 brains (CAG-Spa1). (D) Immunohistochemisty of neuronal marker Hu. The CAG-Spa1 expressed cell is positive for Hu. (E, F) Cerebral cortices (E16.5) electroporated at E14.5. CAG-Spa1 positive cells were observed from the VZ (arrows) to the IMZ (arrowheads) (E), whereas Tα1-Spa1 positive cells were mainly observed in the IMZ (arrowheads) (F). (G–K) Cerebral cortices (P0.5) electroporated at E14.5. Note that neither CAG-Spa1+N-cadherin nor DN-C3G+N-cadherin could rescue the terminal translocation failure. (L) Statistical analyses of GFP-positive cells within the NeuN-negative PCZ (arrows) shown in (G–K). **, p<0.01. n=6 or 7 brains. Scale bars, 100 μm (A, C), 50 μm (B, E–K), 10 μm (D). See also Figure S2.

Rap1 regulates cadherin functions by changing its expression level on the cell surface (Jossin and Cooper, 2011). Since the Rap1-N-cadherin pathway regulates neuronal migration below the CP (Jossin and Cooper, 2011), we next examined whether this pathway might also regulate terminal translocation. Interestingly, although co-transfection of N-cadherin with CAG-Spa1 could rescue the neuronal entry into the CP (Figure S2H, I), co-transfection of these vectors or even co-transfection of N-cadherin with DN-C3G could not rescue the terminal translocation failure (Figure 2G–L). These data suggest that N-cadherin alone is not sufficient to support terminal translocation regulated by the C3G-Rap1 pathway. Thus, we assumed that Reelin might change the Rap1 function through the Dab1-Crk/CrkL-C3G pathway beneath the PCZ to regulate other/additional pathways for terminal translocation and layer formation.

The activated integrin β1 is localized in the leading process of migrating neurons during terminal translocation

Because a previous study has suggested that terminal translocation may be independent of the radial glial fibers (Nadarajah et al., 2001), we hypothesized that a specific adhesion molecule(s) between the migrating neurons and the extracellular environment, such as ECM, might be required for terminal translocation. We previously observed, by in situ hybridization, that fibronectin, one of the major integrin ligands, is expressed on the neurons in the developing CP, especially those in the PCZ (Tachikawa et al., 2008). Interestingly, we found that the fibronectin protein was localized in the Reelin-positive MZ, the site of anchorage of the leading processes of the translocating neurons (Figure 3A, Figure S3A). Since Rap1 can also regulate the integrin functions (Bos, 2005), we then examined the possibility of involvement of the integrins in terminal translocation.

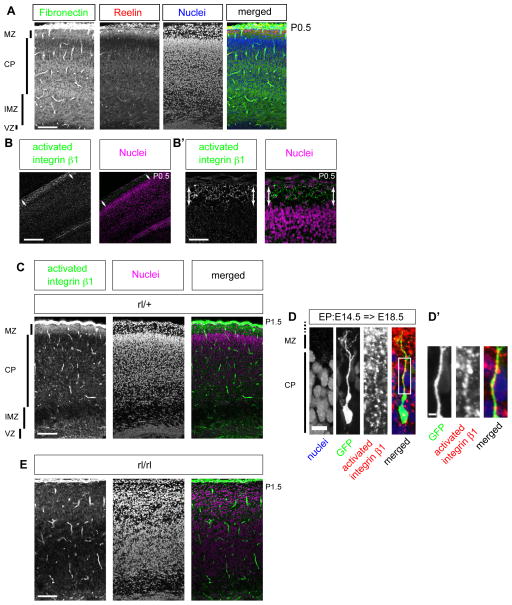

Figure 3. Integrin β1 is activated in the leading process of the translocating neurons.

(A, B, B′) Immunohistochemistry for fibronectin, Reelin, and activated integrin β1. (A) PFA-fixed P0.5 cortex. Note the positive staining for fibronectin (green) in the Reelin (red)-positive MZ as well as in the deep part of the CP and IMZ. (B) Fresh frozen sections of the P0.5 cortex. Activated integrin β1 was detected in the MZ by 9EG7 antibody (green). (B′) Higher magnification view of (B). (C) PFA-fixed sections of heterozygous mutant of Reelin (P1). Activated integrin β1 was detected in the MZ (green). (D) Cerebral cortices (E18.5) electroporated at E14.5. Note that integrin β1 is activated in the leading process which attached to the MZ. (D′) is a higher magnification of the white square of (D). (E) PFA-fixed sections of reeler mutant which is a littermate of (C) (P1). Note that there is no obvious accumulation of the activated integrin β1. Scale bars, 100 μm (A, C, E), 200 μm (B), 50 μm (B′), 10 μm (D), 2.5 μm (D′). See also Figure S3.

Integrin β1 is one of the most highly expressed integrins in the developing neocortex (Belvindrah et al., 2007), and we found strong localization of “activated” integrin β1 in the MZ by using an activated-conformation-specific antibody, 9EG7 (Bourgin et al., 2007) (Figure 3B, B′, C). In addition, we also found a high degree of accumulation in the MZ of the intracellular protein Talin, which is essential for the activation of integrins (Shattil et al., 2010) (Figure S3B). Importantly, activated integrin β1 was localized in the leading processes of the migrating neurons in the MZ (Figure 3D, D′), where nestin-positive radial glial endfeet or MAP2-positive dendrites were present (Figure S3C, D). Furthermore, the accumulation of 9EG7 signals was significantly decreased in the cortex of Reelin-signaling-deficient mice such as reeler, yotari (Dab1-deficient mice) and ApoER2/VLDLR double-knockout mice (Figure 3E, Figure S3E–G). The results of these immunohistochemical analyses suggest the possibility that the Reelin signal controls the activation of integrin β1 and that activated integrin β1 is involved in the terminal translocation mode.

Reelin activates integrin α5β1 through intracellular “inside-out signaling” and promotes neuronal adhesion to fibronectin

Integrins bind to specific extracellular ligands and transmit their signals into the cytoplasm by “outside-in signaling”. Conversely, the ligand-binding activities of integrins are controlled through intracellular pathways stimulated by several environmental factors (“inside-out signaling/activation” (Hynes, 2002) (Shattil et al., 2010)). To examine the possibility that Reelin signaling controls integrin activation, we first performed in vitro integrin activation assays. Reelin stimulation of E14.5 primary cortical neurons plated onto fibronectin-coated dishes significantly increased 9EG7 antibody binding without affecting the total amount of integrin β1 (Figure 4A–A″), suggesting that Reelin stimulation activates integrin β1.

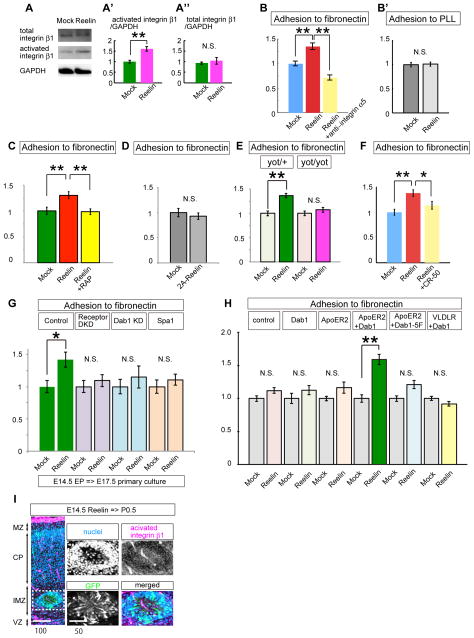

Figure 4. Reelin regulates the inside-out activation of integrin α5β1.

(A–A″) in vitro integrin activation assay using primary cortical neurons at E14. The amount of activated integrin β1 was quantified by the amounts of bound 9EG7 antibody. n=6, ** p=0.00209. (B, B′) Cell adhesion assay using the primary cortical neurons at E16. Note that the Reelin-dependent promotion of neuronal adhesion to fibronectin was blocked by co-treatment with a functional blocking antibody for integrin α5 (MFR5). n=4. **, p<0.01. No adhesion to the BSA-coated dishes was observed, irrespective of the presence/absence of Reelin (data not shown). (C) Reelin-dependent cell adhesion was blocked by co-treatment with receptor associated proteins (RAP). ** p<0.01. (n=3) (D) 2A-Reelin mutant could not promote neuronal adhesion to fibronectin. (n=3) (E) Reelin-dependent cell adhesion was not observed in the primary cortical neurons obtained from Dab1-deficient mice (yotari). ** p<0.01 (n=3) (F) Reelin-dependent cell adhesion was blocked by co-treatment of function-blocking antibody to Reelin (CR-50). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 (n=3) (G) Cell adhesion assay using the migrating neurons at E17.5 electoporated at E14.5. Note that Reelin-dependent promotion of adhesion to fibronectin was significantly impaired in the Reelin-receptor KD neurons, Dab1-KD neurons, or Spa1-overexpressing neurons. n=4. *, p<0.05. (H) Cell adhesion assay using reconstructed HEK-293T cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Note that Reelin promoted cell adhesion to fibronectin only when both ApoER2 and Dab1 were transfected. n=3. **, p<0.01. (I) PFA-fixed cerebral cortices (P0.5) electroporated with pCAGGS-Reelin at E14.5. Neuronal aggregates were observed in the IMZ (white square). Magenta signal shows activated integrin β1 detected using 9EG7 antibody. Right four panels are the higher magnification view of this aggregate. Note that integrin β1 is highly activated in the cell-sparse center of this aggregate. Scale bars, 100 μm (I, left panel), 50 μm (I, right panels). See also Figure S4.

Next, we conducted an adhesion assay to examine whether Reelin stimulation could promote neuronal adhesion to fibronectin. While the adhesion of the primary cortical neurons to the poly-L-lysine (PLL)-coated dishes was not affected by Reelin, the adhesion of the cells to the fibronectin-coated dishes was significantly promoted by the transient Reelin stimulation (Figure 4B, B′). The effects of Reelin were nullified by co-treatment of the cells with an integrin α5β1-function-blocking antibody (MFR5) (Kinashi and Springer, 1994). Because the binding of Reelin to the extracellular region of integrin α5β1 was significantly weaker than that to ApoER2 and VLDLR (Figure S4A), these data suggest that Reelin might promote the adhesiveness of integrin α5β1 to fibronectin via triggering the intracellular inside-out activation cascade through its receptors, ApoER2/VLDLR.

To address the involvement of Reelin-signaling pathways in the activation of integrin α5β1, we first examined the requirement of ApoER2/VLDLR or Dab1 by introducing KD vectors into the primary cortical neurons and performed the integrin activation assays (Figure S4B). Reelin-dependent integrin β1 activation was significantly suppressed under these KD conditions. We next performed cell adhesion assays using the conditioned medium of RAP (receptor-associated-protein) which competitively blocks the binding of Reelin to its receptors (Andersen et al., 2003), the conditioned medium of 2A-Reelin, which is a mutant form of Reelin lacking the ability to bind to the Reelin-receptors (Yasui et al., 2007), or the primary cortical neurons obtained from yotari mice (Figure 4C–E). Reelin-dependent neuronal adhesion to fibronectin was significantly suppressed under each of the above conditions. Furthermore, the effects of Reelin were also canceled by the co-treatment with the CR-50 antibody (Figure 4F), a function-blocking Reelin antibody (Nakajima et al., 1997). To further address the requirement of the Reelin-signaling pathway for neuronal adhesion to fibronectin during neuronal migration, we carried out in utero electroporation to introduce ApoER2/VLDLR double KD vectors, Dab1-KD vectors, or Spa1 at E14.5 and performed cell adhesion assays 3 days after the electroporation (Figure 4G). As the results, Reelin-dependent neuronal adhesion to fibronectin was significantly impaired, suggesting the involvement of the ApoER2/VLDLR-Dab1-Rap1 pathway in the Reelin-dependent promotion of neuronal adhesion to fibronectin during neuronal migration.

In order to confirm whether Reelin can indeed activate integrins through the Reelin receptors-Dab1 pathway, we next conducted a reconstruction experiment using a non-neuronal cell line, HEK-293T cells, to examine the effects of Reelin-Dab1 signaling in integrin activation, because not only integrins but also the integrin-activation molecules such as Crk/CrkL, C3G, Rap1, and Talin are ubiquitously expressed in many kinds of cells, including 293T cells. We transfected Dab1 and ApoER2 into 293T cells and conducted adhesion assays to examine the adhesiveness of the cells to fibronectin. The adhesiveness of reconstructed 293T cells was promoted in the presence of Reelin, whereas this effect was not observed following transfection of Dab1-5F with ApoER2 (Figure 4H), suggesting that Reelin-dependent Dab1 phosphorylation mediated by ApoER2 can activate the cellular adhesiveness to fibronectin even in the reconstructed cells. We also noticed that the cotransfection of VLDLR and Dab1 failed to promote cell adhesion, suggesting that Reelin-dependent cell adhesion to fibronectin was more dependent on ApoER2 than on VLDLR in the 293T cells. This may be related to the fact that the effects of ApoER2 and VLDLR on neuronal migration differ from each other (Hack et al., 2007). Collectively, these data indicate that Reelin can activate integrin α5β1 and promote cellular adhesion to fibronectin via the Reelin receptors-Dab1-Rap1 pathway.

We next investigated whether Reelin could activate integrin β1 in vivo by overexpressing Reelin in the migrating neurons by in utero electroporation. Previously, we reported that ectopic expression of Reelin in the migrating neurons stimulated radial-glia-independent migration similar to terminal translocation and caused neuronal aggregation, resembling the events occurring in the MZ and the top of the CP (Kubo et al., 2010). The 9EG7 antibody clearly recognized this ectopic aggregate, as well as the cell-sparse center resembling the MZ (Figure 4I, S4C), suggesting that even the ectopically expressed Reelin activates integrin β1 in migrating neurons in vivo. These results also support the notion that the “activated” integrin β1 in the MZ showing strong 9EG7 staining (Figure 3B–D) contains the processes of neurons, whereas some radial glial endfeet may also be included (Figure S3C) (Belvindrah et al., 2007).

To examine the requirement of the Reelin-Dab1 signaling for the inside-out activation of integrin in vivo, we examined the intracellular localization of Talin. Co-transfection of HA-tagged Talin with GFP showed polarized distribution of Talin in the leading processes localized in the MZ, where integrin β1 was activated (Figure S4D). Following Dab1 knockdown, however, the HA-tagged Talin was evenly distributed in both the leading processes and the cell somata in more cells than the control, suggesting the requirement of Reelin-Dab1 signaling for the polarized distribution of Talin to the leading processes during terminal translocation.

Integrin α5β1 is required for terminal translocation

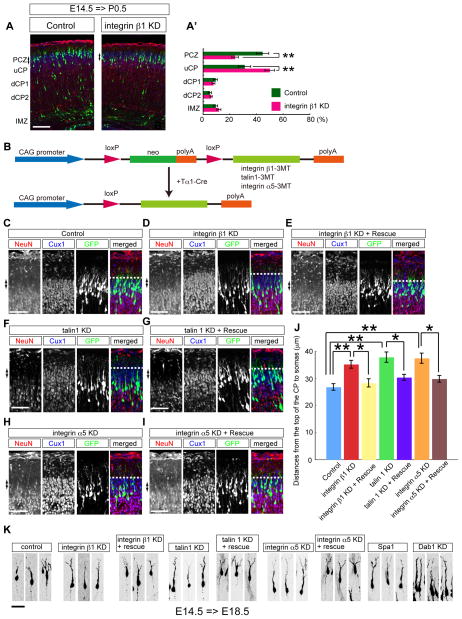

Next we investigated the role of integrins for neuronal migration. Consistent with the localization of activated integrin β1 in the MZ, we found that KD of integrin β1 by in utero electroporation specifically affected terminal translocation (Figure 5A, D, J, S5A, E, F). In addition, KD of Talin 1 also affected terminal translocation (Figure 5F, J, S5B). To assess whether the terminal translocation failure under the aforementioned circumstances was specifically caused by the KD of integrin β1 or of Talin1 in the neurons rather than that in the radial glial cells, we co-transfected the cells with Tα1-controlled expression vectors for integrin β1 or Talin 1 (Figure 5B). Both successfully rescued the KD phenotype (Figure 5E, G, J), suggesting the involvement of the integrin β1 expressed in the neurons rather than that in the radial glial cells in terminal translocation.

Figure 5. Involvement of integrin α5β1 in terminal translocation.

(A) Effects of integrin β1 KD for terminal translocation. Cerebral cortices (P0.5) electroporated at E14.5. Note that integrin β1-KD neurons could not enter the PCZ. (A′) Graphs show the estimation of cell migration of (A). (B) Schemes of plasmids used in the rescue experiments. (C–I) Integrin β1, talin1, and integrin α5 in neurons were required for terminal translocation. Cerebral cortices (P0.5) electroporated at E14.5. Arrows show the PCZ. Note that each resistant vector expressed under the control of a Tα1 promoter rescued the effects of each KD vector. (J) Statistical analyses of terminal translocation failure. **, p<0.01, *, p<0.05. n=6–9 brains. (K) Morphological analyses of neurons (E18.5) electroporated at E14.5. Scale bars, 100 μm (A), 50 μm (C–I), 25 μm (K). See also Figure S5.

The specificity of the interaction between the ECM and integrins is mainly determined by the α subunit of integrin (Hynes, 2002). For example, integrin α5β1 is a major fibronectin receptor, whereas integrin α3β1 is a laminin receptor. We found that KD of integrin α5 resulted in terminal translocation failure (Figure 5H, I, J, S5C), whereas KD of integrin α3 had no such effect (Figure S5D, G). We also closely examined the morphologies of the neurons after they have completed their migration around the PCZ. We introduced a very small amount of the Tα1-Cre vectors together with a pCALNL-GFP vector to sparsely label the transfected neurons (see supplemental experimental procedures) (Figure S5H). Four days after the electroporation, most of the control neurons were found to be located within the PCZ, whereas the integrin β1 KD neurons, integrin α5 KD neurons, Talin 1 KD neurons, and Spa1 overexpressing neurons were located just beneath the PCZ, and the distances between the branch point of the leading processes observed just above the CP and the nuclei of these transfected neurons were also significantly longer than those in the controls (Figure 5K, S5J). These data suggest that the Rap1-Talin1-integrin α5β1 pathway is required for terminal translocation during neuronal migration. In addition, although most of these transfected neurons had a trailing process and a branched leading process, the number of leading process branches was also reduced in these transfected neurons as compared with that in the control neurons (Figure 5K, S5I). Interestingly, however, many Dab1-KD neurons had an elongated leading process with no branch point at this time-point (Figure 5K, S5I), consistent with a previous report (Olson et al., 2006). These results of our morphological analyses suggest that the existence of some differences in role between the Dab1 and the Rap1-integrin α5β1 pathway in dendrite maturation.

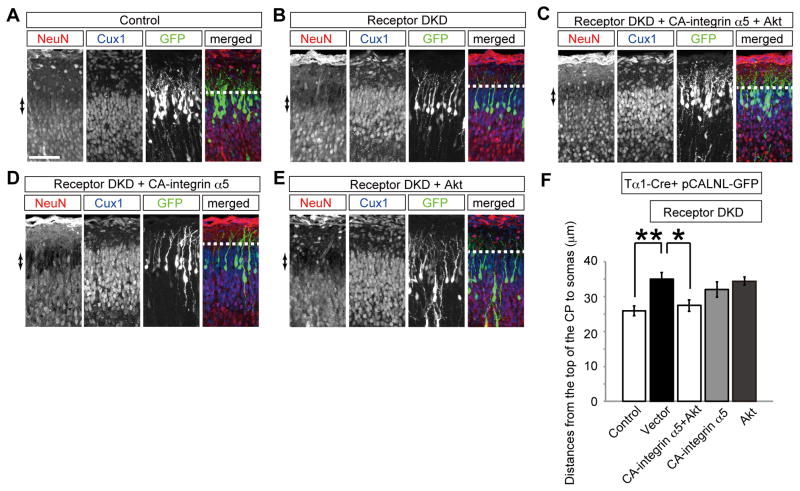

Integrin α5β1 regulates terminal translocation downstream of Reelin

The above-mentioned results prompted us to examine whether integrin α5β1 might control terminal translocation as downstream of Reelin signaling in vivo. Conformational changes of the cytoplasmic domains of integrins are involved in the inside-out signaling. Both α and β integrin subunits possess conserved cytoplasmic domains that interact with each other to inactivate the integrin functions. It is known that a point mutation in the intracellular GFFKR motif of the α subunit can constitutively promote integrin signaling (Shattil et al., 2010). Therefore, we generated a mouse GFFKA mutant of integrin α5 (constitutively active integrin α5; CA-integrin α5), whose expression was controlled by a Tα1-Cre vector (Figure. 5B), and examined whether this mutant could rescue the terminal translocation failure caused by disrupted Reelin signaling. Co-transfection of KD vectors for ApoER2 and VLDLR affected the terminal translocation as we previously reported (Figure 6A, B, F) (Kubo et al., 2010). Although this terminal translocation failure was not fully rescued by co-transfection with the CA-integrin α5 alone (Figure 6D, F), it was almost entirely rescued by co-transfection with CA-integrin α5 and a wild-type Akt expression vector, which is also known to be involved in Reelin signaling (Feng and Cooper, 2009) (Chai et al., 2009) (Jossin and Cooper, 2011) (Figure 6C, F); wild-type Akt alone could not rescue the terminal translocation failure (Figure 6E, F). These data suggest that integrin α5β1 regulates terminal translocation cooperatively with Akt as a downstream molecule in the Reelin signaling pathway.

Figure 6. Reelin activates integrin α5β1 during terminal translocationin vivo.

(A–E) Rescue of the terminal translocation failure caused by ApoER2/VLDLR double KD (DKD). Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Note that co-transfection of CA-integrin α5 and Akt rescued the terminal translocation failure. Arrows show the PCZ. (F) Statistical analyses of (A–E). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. n=8–12 brains. Scale bar, 50 μm (A).

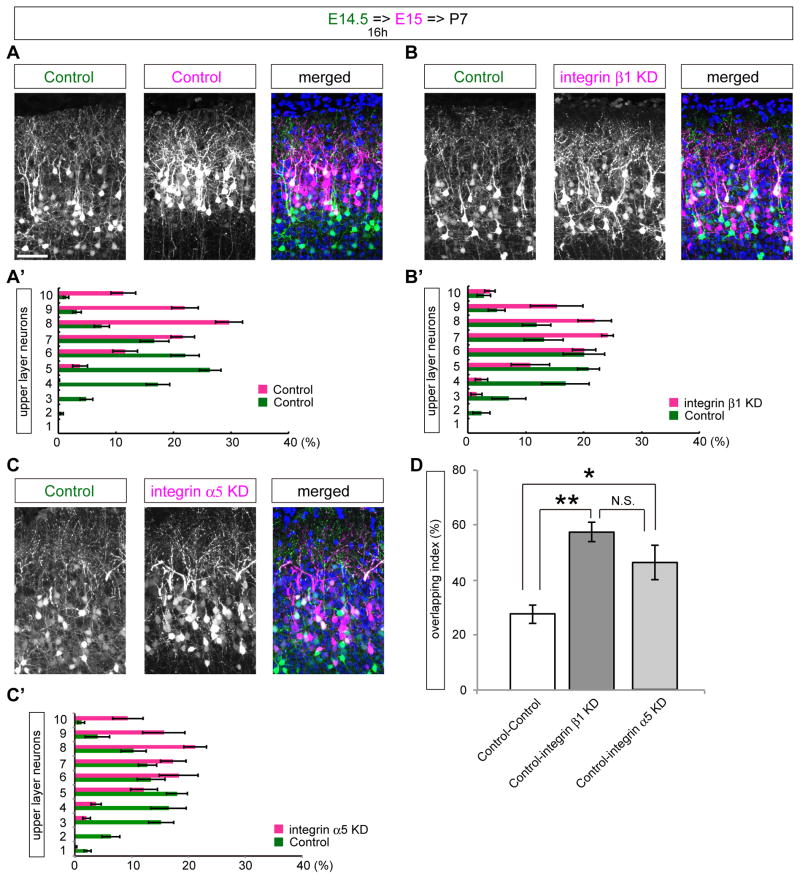

Integrin α5β1 is required for proper neuronal alignment in the mature cortex

Birth-date-dependent “inside-out” neuronal layering is the hallmark of the effects of Reelin-Dab1 signaling. To examine the effects of integrin α5β1 in the eventual pattern of neuronal alignment in the mature cortex, we performed sequential in utero electroporation (Sekine et al., 2011). We introduced a GFP-expression vector at E14.5 to label the earlier-born neurons. Since the length of the cell cycle at this stage is about 15–16 hours (Takahashi et al., 1995), we electroporated a control vector, an integrin α5 KD vector, or an integrin β1 KD vector along with an mCherry-expressing vector 16 hours after the first electroporation to label the later-born neurons in the same cortex. At P7, when all the neuronal layers are established, the control-control case showed a clearly segregated birth-date-dependent inside-out pattern (Figure 7A, A′). In contrast, this highly segregated inside-out pattern of neuronal alignment was significantly disrupted in the control-integrin α5 KD or control-integrin β1 KD cases (Figure 7B–D). These data suggest that the terminal translocation failure caused by integrin α5 or β1 KD results in the disruption of the final pattern of neuronal positioning in the mature cortex.

Figure 7. Integrin α5β1 is required for the eventual neuronal positioning in the mature cortex.

(A–C) Sequential in utero electroporation examined at P7 electroporated with the indicated plasmids. Note that KD of integrin α5 or integrin β1 in later-born neurons affected the inside-out arrangement of neurons in the mature cortex. (A′–C′) Bin analyses of (A–C). Layer II–IV was divided into 10 bins. (D) Overlapping index of sequential electroporation. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. n=9 (control-control case), n=7 (control-integrin β1 KD case), n=8 (control-integrin α5 KD case). Scale bar, 50 μm (A).

Discussion

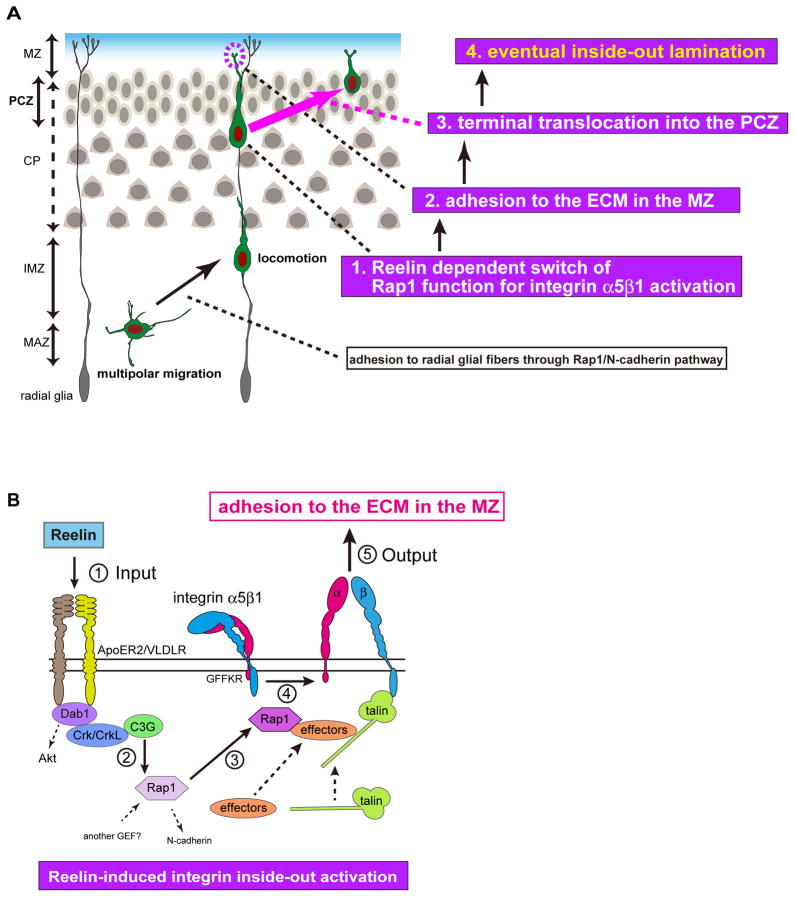

The bidirectional interactions between migrating cells and their surrounding environment are fundamental for the establishment of functional multicellular organ systems, and are also closely involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases, such as metastases and inflammatory diseases. In many cases, environmental factors play central roles to influence the behaviors of migrating cells in a spatio-temporal manner. Integrin receptors are also important for this bidirectional interaction, because integrins can transmit the signals between the outside and inside of the cells (Hynes, 2002). In this study, we identified that Reelin, as an extrinsic factor, switches the function of Rap1 during terminal translocation and thereby activates integrin α5β1 through the biologically conserved inside-out signaling cascade (Shattil et al., 2010). We also found that this integrin activation changes the neuronal migration mode by promoting neuronal adhesion to the ECM protein, such as fibronectin, and that this interplay between migrating neurons and the ECM is crucial to establish the eventual birth-date-dependent layering pattern of neurons in the mature cortex (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Reelin dependent switch of adhesion molecules controls terminal translocation and inside-out lamination.

(A) Scheme of the migratory mode changes. Multipolar migrating neurons change their migratory behavior to locomotion through Rap1, and adhere to the radial glial fibers in a N-cadherin-dependent manner. When the locomoting neurons reach beneath the PCZ, at which site a dense accumulation of immature neurons is observed, Reelin triggers the C3G-dependent Rap1 pathway for integrin activation. Then, the leading processes of the locomoting neurons adhere to the ECM, such as fibronectin in the MZ through integrin α5β1 and change their migratory mode to terminal translocation. The interaction between migrating neurons and ECM is fundamental for the eventual neuronal layering in the mature cortex. (B) Scheme of Reelin-dependent integrin α5β1 inside-out activation. 1. Reelin (input) phosphorylates Dab1 through ApoER2/VLDLR, recruits Crk/CrkL, and phosphorylates C3G. 2. C3G activates Rap1. 3. Activated Rap1 recruits some effectors, and 4. the conformation of the integrin subunits change. 5. Finally, activated integrin α5β1 adheres to fibronectin in the MZ to mediate terminal translocation and layer formation (output).

The roles of the integrin family in the neuronal migration in the neocortex have been under debate (Belvindrah et al., 2007) (Anton et al., 1999) (Dulabon et al., 2000) (Magdaleno and Curran, 2001) (Schmid et al., 2004) (Sanada et al., 2004) (Luque, 2004) (Marchetti et al., 2010). It was reported using knockout mice that integrin β1 in neurons was not required for layer formation (Belvindrah et al., 2007), whereas integrin α3, which heterodimerizes only with integrin β1, was expressed below the CP and was required for neuronal migration (Anton et al., 1999) (Dulabon et al., 2000) (Schmid et al., 2004). It is possible that these discrepancies were partly caused by the possible redundancy of the large number of integrin subunits expressed in the developing neocortex (Pinkstaff et al., 1999) or the integrin trans-regulatory mechanisms (Calderwood et al., 2004). In this study, we revealed that acute downregulation of integrin β1 and integrin α5 by in vivo RNAi methods disturbed the terminal translocation of neocortical neurons. Although a recent study also showed that acute depletion of integrin α5 somehow delayed the neuronal migration (Marchetti et al., 2010), these neurons could not pass through the PCZ, which is consistent with our findings. In addition, it is also possible that there might be some abnormal neuronal positioning even in integrin β1-knockout mice, because our sequential control-integrin β1 KD experiments showed that the birth-date-dependent segregation pattern between the later-born integrin β1 KD neurons and the earlier-born control neurons was significantly disrupted, with more overlap of the distribution than the control-control experiments.

We also identified that Rap1 is an intracellular signal transducer that relays the upstream signals to distinct downstream adhesion molecules during neuronal migration. In general, the different roles of a small GTPase involve functionally distinct effectors, and the selection of the specific effector of the small GTPase depends on the spatially and temporally distinct activation of the specific GEFs (Vigil et al., 2010). In this study, we found that Rap1 has dual functions in neuronal migration and that the effects of Rap1 on integrin α5β1 beneath the PCZ were activated by C3G, whereas the effects of Rap1 on N-cadherin beneath the CP seemed to be activated not by C3G, but by another Rap1 GEF (Figure 8). Among the several kinds of Rap1 GEFs, recent genetic studies suggested that C3G and RA-GEF1 (also known as PDZ-GEF) had distinct functions in neuronal migration; C3G-mutant mice showed failure of preplate splitting, just like Reelin- or Dab1-mutant mice (Voss et al., 2008), whereas RA-GEF1 knockout, while not affecting the preplate splitting, caused migration failure of neurons before they entered the CP (Bilasy et al., 2009). We previously suggested that low amounts of Reelin and its functional receptors are present below the CP (Uchida et al., 2009), and another study showed that Reelin signaling is somehow required for the neuronal migratory behavior below the CP through Rap1/N-cadherin pathway (Jossin and Cooper, 2011). However, the disruption of this Reelin-Rap1-N-cadherin signaling is not likely to be the only reason for the roughly inverted laminar organization in Reelin-signaling-deficient mice, because even the Dab1-depleted neurons could migrate into the CP and reach just beneath the PCZ by locomotion (Olson et al., 2006) (Franco et al., 2011) (Sekine et al., 2011). In contrast, high expression levels of Reelin in the MZ activate C3G during terminal translocation, which in turn, activates the Rap1/integrin α5β1 pathway to form the eventual pattern of Reelin-dependent neuronal layering within the PCZ. Therefore, Reelin can switch the adhesion molecules to mediate the dual functions of Rap1 in neuronal migration. In addition, given the idea that translocation is the phylogenetically conserved radial glia-independent mode of migration (Nadarajah et al., 2001) as compared to the evolutionally acquired radial glia-guided locomotion (Rakic, 1972), it is easy to conceive that different adhesion molecules are involved in the different migratory modes, i.e. N-cadherin for locomotion (Kawauchi et al., 2010) and integrin α5β1 for terminal translocation.

We demonstrated that constitutively active integrin α5 could rescue the terminal translocation failure, cooperatively with Akt, in Reelin receptors-knockdown neurons. However, we also observed that co-transfection of the mutated integrin α5 and Akt could not rescue the Dab1-knockdown phenotype (data not shown). One explanation for this failure is that Dab1 itself may be involved in the regulation of integrin functions through interaction between its PTB domain and the NPxY motif of integrin β1 (Schmid et al., 2005). An alternative explanation is that Dab1 may regulate some cellular functions independent of Reelin stimulation (Honda et al., 2011). We also failed to rescue the migration failure in the reeler mutant cortex by co-transfection of CA-integrin α5 and Akt (data not shown). Although there is no obvious PCZ-like structure in the reeler cortex (Sekine et al., 2011), a previous study using Dab1 chimeric mice showed that most Dab1 +/+ cells could migrate in the Dab1 −/− environment (Hammond et al., 2001). In addition, another study using ectopic expression of Reelin in the VZ showed partial rescue of migration of some neurons during preplate splitting (Magdaleno et al., 2002). Because integrin α5β1-dependent terminal translocation is the specific migration mode around the PCZ in the wild-type cortex, it is possible that the abnormal layering in the reeler cortex was caused or modified by other/additional mechanisms including, for example, abnormal formation of the internal plexiform zone in the reeler cortex (Tabata and Nakajima, 2002). Future studies using genetically engineered mice will be needed to fully address the role of Reelin-induced integrin activation for the layer formation.

Terminal translocation is thought to share some mechanisms with somal translocation of the earliest-born neurons (Nadarajah et al., 2001). A recent study showed that N-cadherin is required for somal translocation (Franco et al., 2011). However, N-cadherin regulation by Reelin during somal translocation was not directly shown, and it was described that Dab1-null migration phenotype was not rescued by overexpression of N-cadherin. Consistently, we also observed that N-cadherin alone was not sufficient to rescue the terminal translocation failure observed after transfection of DN-C3G. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that N-cadherin is also required for terminal translocation, because N-cadherin-KD neurons showed aberrant termination of migration before the cells reached the PCZ (Kawauchi et al., 2010). One possibility is that Reelin might change the subcellular localization of N-cadherin during terminal translocation to cooperatively regulate terminal translocation with integrin α5β1, because previous immunohistochemical analyses have revealed intense N-cadherin staining in the MZ (Franco et al., 2011), but only weak staining on the top of the CP (Kawauchi et al., 2010). Alternatively, there is the other possibility that the mechanisms underlying terminal translocation are different from those of somal translocation, because neurons need to pass through the cell-dense PCZ during terminal translocation, unlike the cell-sparse preplate in the case of neurons showing somal translocation (Sekine et al., 2011).

How does activated integrin α5β1 regulate terminal translocation? Because the cell somata are thought to be pulled with shortening of the leading processes and because activated integrin β1 is strongly localized in the leading processes which anchor to the fibronectin-positive MZ, we hypothesize that traction forces are generated at the leading processes through the integrin α5β1 “outside-in” signaling. A recent in vitro study supported this model by showing the presence of traction forces at the tips of the leading processes (He et al., 2010). Our data also showed that Akt plays some role in terminal translocation, which is consistent with a previous finding that Reelin reorganizes the actin cytoskeletons in the leading processes through phosphorylation of n-cofilin via Akt (Chai et al., 2009). Microtubules in the leading processes must also be reorganized for the shortening of the leading process, and the microtubule dynamics is also coupled to the forward movement of the nuclei (Tsai and Gleeson, 2005) (Zhang et al., 2009). Therefore, we reason that the leading processes play the primary role in the terminal translocation of the neocortical neurons. However, recent in vitro analyses of neuronal migration under the Matrigel condition, in which radial glial fibers do not exist, suggested that there is also the other possibility that the contraction of myosin II behind the nuclei and endocytosis of adhesion molecules just proximal to the cell somata are involved in the pushing up of the cell somata (Schaar and McConnell, 2005) (Shieh et al., 2011). Future in vivo studies will be needed to elucidate the detailed mechanisms underlying neuronal migration in the neocortex, which will lead to revelation of the complex mechanisms of neuronal layer formation.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Pregnant ICR mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). The colony of reeler mice (B6CFe a/a-Relnrl/J) obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) was maintained by allowing heterozygous females to mate with homozygous males. The day of vaginal plug detection was considered to be embryonic day 0 (E0). The ways to maintain the colony of yotari mice or ApoER2/VLDLR double knockout mice were previously described (Tabata and Nakajima, 2002) (Trommsdorff et al., 1999). All the animal experiments were performed according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Keio University.

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this study are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

In utero electroporation

In utero electroporation was performed as described previously (Tabata and Nakajima, 2001), and was also described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Sekine et al., 2011). The primary antibodies used are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Fresh frozen sections

Brains were removed directly in ice-cold PBS, embedded in O.C.T. compound and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen-cold 2-propanol. The prepared cryosections were fixed in 100% acetone at −20°C for 10 min. After washing with PBS-Tx, rat anti-activated integrin β1 antibody (1:10, 9EG7; BD Pharmingen) was added to the sections.

Statistical analyses of neuronal migration

In coronal sections of the fixed embryonic brains obtained from several pregnant mice, the caudal part of the somatosensory cortex was selected for the measurements. The distances from the top of the CP to the nuclei of the migrating cells which were visualized by DAPI staining were blindly measured using the ImageJ software (NIH).

Morphological analyses

To determine the morphological structures of the terminal translocating neurons, z series of transfected brains were acquired at 1μm intervals through 10–20 μm using a 40 × objective. These z series were reconstructed using FV1000 (Olympus), and the morphologies of the GFP-positive cells attached to the MZ were analyzed using the ImageJ software.

Immunoabsorption

A 1.5-ml tube was coated with 10% BSA-PBS at 4°C for 30 min. Rabbit anti-mouse fibronectin antibodies (1:500 AB2033, Chemicon) and rat plasma fibronectin (1 mg/ml, F0635, Sigma) were incubated in 1% BSA-PBS O/N at 4°C. The supernatant obtained after centrifugation (10,000 g, 1hr, at 4°C) of the solution was subjected to immunohistochemistry.

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin (DIG)-tagged antisense and sense RNA probes for Rap1a and Rap1b were synthesized using FANTOM clones. Detailed procedures are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Western-blot analysis

Western-blot analysis was performed as described previously (Sekine et al., 2011). The procedures for the transfection into the primary cortical neurons were previously described (Kawauchi et al., 2010). Detailed procedures and primary antibodies are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Preparation of Reelin-conditioned medium

HEK-293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-Reelin vector or pCAGGS-Control vector using the GeneJuice transfection reagent (Merck). Detailed procedures are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Integrin activation assay

The integrin activation assay was performed as described previously (Bourgin et al., 2007), with some modification. E14 embryonic cortices were dissociated and were plated onto the coated dish containing control- or Reelin-conditioned serum-free medium and incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C. After washes, 9EG7 antibody (2 μg/ml in DMEM) was applied, followed by incubation for 15 minutes at 37°C. After washes, the cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer. Bound 9EG7 antibodies were detected using biotin-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG (1:2000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:2000, Perkin Elmer). Detailed procedures are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Cell adhesion assay

Cell adhesion assay was performed as described previously (Bourgin et al., 2007), with some modification. E16 embryonic cortices were dissociated, stimulated with Reelin-conditioned medium for 15 minutes at 37°C, and plated onto the coated wells (7×104 cells per well) filled with DMEM for 5 minutes at 37°C. Then, after three washes with warm DMEM, the attached cells were counted (nine microscopic fields (20×) were counted in each well). Detailed procedures are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Ratiometric analyses

The fluorescence intensity of GFP and Dylight-549 was detected using FV1000. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical analyses

For direct comparisons, the data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney’s U test (n<10). For multiple comparisons, ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey’s posthoc test. All bar graphs were plotted as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences (“Understanding of molecular and environmental bases for brain health”), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Global COE Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Science and Technology of Japan, and Keio Gijuku Academic Development Funds. J.H. is supported by grants from the NIH, AHAF, the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research and SFB780. We thank Drs. J. Cooper, F. Miller, M. Matsuda, H. Kitayama, L. Huganir, T. Tsuji, M. Ginsberg, C. Cepko, T. Miyata, and J. Miyazaki for providing the plasmids, and all the members of the Nakajima laboratory for discussion. K.S. is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five Supplemental Figures and Legends, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Author contribution

K.S. designed and performed all the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.Ka. supported to design the initial experiments, to analyze the data, and to write the manuscript. K.K. supported the preparation of Reelin, performed some in utero electroporation, and analyzed the data. T.H. constructed a part of the Dab1 expression vectors and analyzed the data. J.H. and M.H. provided the mutant mice and J.H. edited the paper. T.Ki. supported to design the integrin experiments and analyzed the data. K.N. supervised the whole project, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersen OM, Benhayon D, Curran T, Willnow TE. Differential binding of ligands to the apolipoprotein E receptor 2. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9355–9364. doi: 10.1021/bi034475p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton ES, Kreidberg JA, Rakic P. Distinct functions of alpha3 and alpha(v) integrin receptors in neuronal migration and laminar organization of the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1999;22:277–289. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala R, Shu T, Tsai LH. Trekking across the brain: the journey of neuronal migration. Cell. 2007;128:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballif BA, Arnaud L, Arthur WT, Guris D, Imamoto A, Cooper JA. Activation of a Dab1/CrkL/C3G/Rap1 pathway in Reelin-stimulated neurons. Curr Biol. 2004;14:606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvindrah R, Graus-Porta D, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Muller U. Beta1 integrins in radial glia but not in migrating neurons are essential for the formation of cell layers in the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13854–13865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4494-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilasy SE, Satoh T, Ueda S, Wei P, Kanemura H, Aiba A, Terashima T, Kataoka T. Dorsal telencephalon-specific RA-GEF-1 knockout mice develop heterotopic cortical mass and commissural fiber defect. The European journal of neuroscience. 2009;29:1994–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JL. Linking Rap to cell adhesion. Current opinion in cell biology. 2005;17:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin C, Murai KK, Richter M, Pasquale EB. The EphA4 receptor regulates dendritic spine remodeling by affecting beta1-integrin signaling pathways. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;178:1295–1307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood DA, Tai V, Di Paolo G, De Camilli P, Ginsberg MH. Competition for talin results in trans-dominant inhibition of integrin activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:28889–28895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X, Forster E, Zhao S, Bock HH, Frotscher M. Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3. J Neurosci. 2009;29:288–299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA. A mechanism for inside-out lamination in the neocortex. Trends in neurosciences. 2008;31:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulabon L, Olson EC, Taglienti MG, Eisenhuth S, McGrath B, Walsh CA, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin binds alpha3beta1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron. 2000;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Cooper JA. Dual functions of Dab1 during brain development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29:324–332. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00663-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco SJ, Martinez-Garay I, Gil-Sanz C, Harkins-Perry SR, Muller U. Reelin Regulates Cadherin Function via Dab1/Rap1 to Control Neuronal Migration and Lamination in the Neocortex. Neuron. 2011;69:482–497. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal JS, Morozov YM, Ayoub AE, Chatterjee M, Rakic P, Haydar TF. Molecular and morphological heterogeneity of neural precursors in the mouse neocortical proliferative zones. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1045–1056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4499-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster A, Wu W, Speelman A, Weiss S, Causing C, Pozniak C, Reynolds B, Chang E, Toma JG, Miller FD. The T alpha 1 alpha-tubulin promoter specifies gene expression as a function of neuronal growth and regeneration in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7319–7330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07319.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack I, Hellwig S, Junghans D, Brunne B, Bock HH, Zhao S, Frotscher M. Divergent roles of ApoER2 and Vldlr in the migration of cortical neurons. Development (Cambridge, England) 2007;134:3883–3891. doi: 10.1242/dev.005447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond V, Howell B, Godinho L, Tan SS. disabled-1 functions cell autonomously during radial migration and cortical layering of pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8798–8808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08798.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Zhang ZH, Guan CB, Xia D, Yuan XB. Leading tip drives soma translocation via forward F-actin flow during neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10885–10898. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0240-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, Herz J. Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 1999;24:481–489. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda T, Kobayashi K, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K. Regulation of cortical neuron migration by the reelin signaling pathway. Neurochemical research. 2011;36:1270–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jossin Y, Cooper JA. Reelin, Rap1 and N-cadherin orient the migration of multipolar neurons in the developing neocortex. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:697–703. doi: 10.1038/nn.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi T, Sekine K, Shikanai M, Chihama K, Tomita K, Kubo K, Nakajima K, Nabeshima Y, Hoshino M. Rab GTPases-dependent endocytic pathways regulate neuronal migration and maturation through N-cadherin trafficking. Neuron. 2010;67:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshvara L, Benhayon D, Magdaleno S, Curran T. Identification of reelin-induced sites of tyrosyl phosphorylation on disabled 1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:16008–16014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:546–559. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi T, Springer TA. Steel factor and c-kit regulate cell-matrix adhesion. Blood. 1994;83:1033–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Honda T, Tomita K, Sekine K, Ishii K, Uto A, Kobayashi K, Tabata H, Nakajima K. Ectopic Reelin induces neuronal aggregation with a normal birthdate-dependent “inside-out” alignment in the developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10953–10966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0486-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JM. Integrin and the Reelin-Dab1 pathway: a sticky affair? Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:269–271. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdaleno S, Keshvara L, Curran T. Rescue of ataxia and preplate splitting by ectopic expression of Reelin in reeler mice. Neuron. 2002;33:573–586. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdaleno SM, Curran T. Brain development: integrins and the Reelin pathway. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R1032–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti G, Escuin S, van der Flier A, De Arcangelis A, Hynes RO, Georges-Labouesse E. Integrin alpha5beta1 is necessary for regulation of radial migration of cortical neurons during mouse brain development. The European journal of neuroscience. 2010;31:399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Valiente M, Ge X, Tsai LH. Guiding neuronal cell migrations. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2010;2:a001834. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah B, Brunstrom JE, Grutzendler J, Wong RO, Pearlman AL. Two modes of radial migration in early development of the cerebral cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2001;4:143–150. doi: 10.1038/83967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, Miyata T, Kudo C, Ogawa M. Disruption of hippocampal development in vivo by CR-50 mAb against reelin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:8196–8201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, Yamamoto H, Mikoshiba K. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EC, Kim S, Walsh CA. Impaired neuronal positioning and dendritogenesis in the neocortex after cell-autonomous Dab1 suppression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1767–1775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3000-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Curran T. Crk and Crk-like play essential overlapping roles downstream of disabled-1 in the Reelin pathway. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13551–13562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkstaff JK, Detterich J, Lynch G, Gall C. Integrin subunit gene expression is regionally differentiated in adult brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1541–1556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01541.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1972;145:61–83. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nature reviews. 2009;10:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DS, Curran T. Role of the reelin signaling pathway in central nervous system development. Annual review of neuroscience. 2001;24:1005–1039. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada K, Gupta A, Tsai LH. Disabled-1-regulated adhesion of migrating neurons to radial glial fiber contributes to neuronal positioning during early corticogenesis. Neuron. 2004;42:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar BT, McConnell SK. Cytoskeletal coordination during neuronal migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:13652–13657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506008102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1632–1636. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid RS, Shelton S, Stanco A, Yokota Y, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. alpha3beta1 integrin modulates neuronal migration and placement during early stages of cerebral cortical development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:6023–6031. doi: 10.1242/dev.01532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine K, Honda T, Kawauchi T, Kubo K, Nakajima K. The outermost region of the developing cortical plate is crucial for both the switch of the radial migration mode and the dab1-dependent “inside-out” lamination in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9426–9439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0650-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh JC, Schaar BT, Srinivasan K, Brodsky FM, McConnell SK. Endocytosis regulates cell soma translocation and the distribution of adhesion proteins in migrating neurons. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Kanatani S, Nakajima K. Differences of migratory behavior between direct progeny of apical progenitors and basal progenitors in the developing cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2092–2105. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Nakajima K. Efficient in utero gene transfer system to the developing mouse brain using electroporation: visualization of neuronal migration in the developing cortex. Neuroscience. 2001;103:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Nakajima K. Neurons tend to stop migration and differentiate along the cortical internal plexiform zones in the Reelin signal-deficient mice. Journal of neuroscience research. 2002;69:723–730. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Nakajima K. Multipolar migration: the third mode of radial neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9996–10001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09996.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa K, Sasaki S, Maeda T, Nakajima K. Identification of molecules preferentially expressed beneath the marginal zone in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuroscience research. 2008;60:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS., Jr The cell cycle of the pseudostratified ventricular epithelium of the embryonic murine cerebral wall. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6046–6057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Herz J. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell. 1999;97:689–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Gleeson JG. Nucleokinesis in neuronal migration. Neuron. 2005;46:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto N, Hattori M, Yang H, Bos JL, Minato N. Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:18463–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Baba A, Perez-Martinez FJ, Hibi T, Miyata T, Luque JM, Nakajima K, Hattori M. Downregulation of functional Reelin receptors in projection neurons implies that primary Reelin action occurs at early/premigratory stages. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10653–10662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0345-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil D, Cherfils J, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Ras superfamily GEFs and GAPs: validated and tractable targets for cancer therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:842–857. doi: 10.1038/nrc2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss AK, Britto JM, Dixon MP, Sheikh BN, Collin C, Tan SS, Thomas T. C3G regulates cortical neuron migration, preplate splitting and radial glial cell attachment. Development (Cambridge, England) 2008;135:2139–2149. doi: 10.1242/dev.016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui N, Nogi T, Kitao T, Nakano Y, Hattori M, Takagi J. Structure of a receptor-binding fragment of reelin and mutational analysis reveal a recognition mechanism similar to endocytic receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:9988–9993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700438104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lei K, Yuan X, Wu X, Zhuang Y, Xu T, Xu R, Han M. SUN1/2 and Syne/Nesprin-1/2 complexes connect centrosome to the nucleus during neurogenesis and neuronal migration in mice. Neuron. 2009;64:173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.