Abstract

The molecular mechanisms linking glucose metabolism with active transcription remain undercharacterized in mammalian cells. Using nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) as a glucose-responsive transcription factor, we show that cells use the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway and O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase (OGT) to potentiate gene expression in response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or etoposide. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrate that, upon induction, OGT localizes to NF-κB–regulated promoters to enhance RelA acetylation. Knockdown of OGT abolishes p300-mediated acetylation of RelA on K310, a posttranslational mark required for full NF-κB transcription. Mapping studies reveal T305 as an important residue required for attachment of the O-GlcNAc moiety on RelA. Furthermore, p300 fails to acetylate a full-length RelA(T305A) mutant, linking O-GlcNAc and acetylation events on NF-κB. Reconstitution of RelA null cells with the RelA(T305A) mutant illustrates the importance of this residue for NF-κB–dependent gene expression and cell survival. Our work provides evidence for a unique regulation where attachment of the O-GlcNAc moiety to RelA potentiates p300 acetylation and NF-κB transcription.

Keywords: p65, NF kappa B, apoptosis

A shunt of glycolysis known as the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) links cellular signaling and gene expression to glucose metabolism (1, 2). The HBP generates a metabolically expensive moiety used for glycosylation, uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) (1, 3, 4). The β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (OGT) enzyme uses UDP-GlcNAc to covalently attach a single O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) moiety to serine or threonine (S/T) residues within target proteins (4). Conversely, O-GlcNAcase (OGA) removes the modification. Both OGT and OGA are essential, ubiquitously expressed enzymes, making O-GlcNAcylation a highly dynamic process (5, 6). O-GlcNAcylation regulates transcription through OGT-associated chromatin-modifying complexes (4, 7–10) and direct modification of transcription factors such as NF-κB (11–15).

NF-κB is a glucose-responsive transcription factor that governs many biological processes including cell proliferation, survival, and inflammation (16, 17). Five NF-κB family members have been identified in humans: RelA/p65, RelB, cRel, p105/p50, and p100/p52. The most prevalent and best studied form of NF-κB is the RelA/p50 heterodimer. Before stimulation, inhibitor of κB alpha (IκBα) sequesters dormant RelA/p50 heterodimers in the cytosol. Canonical induction drives IκB kinase (IKK) complex-mediated phosphorylation of IκBα, resulting in K48-linked polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation via the 26S proteasome (16). The degradation of IκBα allows RelA/p50 heterodimers to translocate to the nucleus where they displace repressive p50 and p52 homodimers at NF-κB–regulated promoters.

In unstimulated cells, p50 or p52 homodimers bind to target promoters and silence gene expression by recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity tethered to nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) or silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid-hormone receptor (SMRT) (18–21). The deacetylase activity of localized HDAC1/2/3 and NAD+-dependent SIRT1/6 sustain the basal repression of these NF-κB–regulated promoters (20, 22–25). Our group has shown that chromatin-associated recruitment of IKKα results in phosphorylation of SMRT, and displacement of the SMRT/HDAC3 corepressor complex, enabling RelA/p50 dimers to activate NF-κB–regulated promoters (21, 23). Once bound to NF-κB–regulated promoters, the acidic-rich transactivation domain of RelA recruits coactivator complexes that include either p300 or the CREB-binding protein (CBP) (20, 26, 27). Histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity of p300/CBP modifies local chromatin structure and facilitates recruitment of the transcriptional machinery, including the TFIID complex and RNA polymerase II (28, 29). Complete NF-κB transcriptional activation requires specific acetylation of RelA lysine 310 (K310) by p300/CBP (23, 25, 30–32).

Because RelA has been shown to be modified by OGT (11, 15), we sought to determine whether attachment of an O-GlcNAc modification impacts RelA acetylation. Data presented in this paper demonstrate that OGT inducibly localizes to chromatin and drives p300-mediated acetylation of RelA(K310). Thus, attachment of the O-GlcNAc moiety to RelA is a prerequisite for K310 acetylation, a molecular mechanism that links glucose metabolism with NF-κB transcription.

Results

Activation of NF-κB Is Glucose-Dependent.

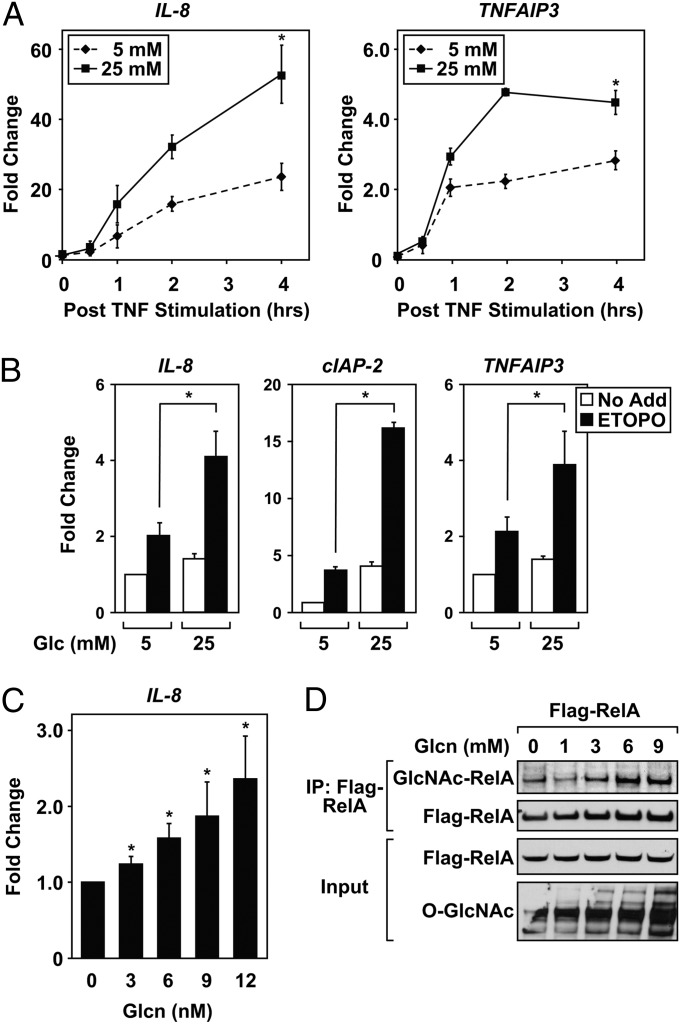

NF-κB is a glucose-responsive transcription factor (17). Using an NF-κB responsive luciferase reporter system, we demonstrate that HEK 293T cells cultured in high glucose (25 mM) show elevated NF-κB transcriptional activity in response to TNF compared with cells cultured in 5 mM glucose (Fig. S1A). Treatment with lower concentrations of TNF (1 ng/mL), rather than 10 ng/mL, showed more sensitivity to change in glucose concentrations (Fig. S1A). For this reason, we used low concentrations of TNF throughout the rest of our studies. Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) demonstrates the induction of NF-κB–regulated genes (IL-8 and TNFAIP3) in cells incubated in high concentrations of glucose compared with cells cultured in 5 mM glucose (Fig. 1A). This effect was not limited to TNF because the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide also stimulated NF-κB regulated genes (IL-8, cIAP-2, and TNFAIP3) in a glucose-responsive manner (Fig. 1B). Because glucose regulates numerous metabolic pathways, cells cultured in 5 mM glucose were treated with d-glucosamine (Glcn) as a way to specifically increase UDP-GlcNAc levels. The addition of Glcn increased IL-8 transcription in a dose-dependent manner after TNF stimulation (Fig. 1C). RelA and total cellular protein show increased O-GlcNAc modification through Glcn-induced upregulation of cytosolic UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 1D). The specificity of the pan anti–O-GlcNAc antibody was confirmed in Fig. S1B. Experiments shown in Fig. 1 are consistent with previous reports (11), indicating that NF-κB responsive transcription is positively regulated by glucose flux through the HBP.

Fig. 1.

Flux through the HBP enhances NF-κB transcription. (A) HEK 293T cells were treated with TNF (1 ng/mL) after overnight incubation in serum-free DMEM containing either 5 mM or high (25 mM) glucose concentrations. Expression of IL-8 (Left) and TNFAIP3 (Right) was quantified by using QRT-PCR, and samples were normalized to GAPDH levels. Fold change values represent comparison with unstimulated cells incubated in 5 mM glucose. (B) HEK 293T cells were cultured overnight in either 5 mM or 25 mM glucose DMEM, and the next day, cells were treated with etoposide (100 μM) for 4 h. QRT-PCR demonstrates elevated NF-κB responsive transcripts in high glucose, compared with cells cultured in 5 mM glucose. Fold change values represent comparison with untreated cells incubated in 5 mM glucose. (C) HEK 293T cells were cultured overnight in 5 mM glucose DMEM. Cells were then exposed to glucosamine (Glcn) for 2 h, stimulated with TNF (1 ng/mL) for 4 h, and QRT-PCR was performed. Fold change represents values obtained from TNF-stumulated cells incubated in the absence of Glcn. (D) HEK 293T cells transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-RelA were incubated in 5 mM glucose media overnight and subsequently exposed to Glcn for 4 h. Flag-RelA was immunoprecipitated, and O-GlcNAc-modified RelA was analyzed by immunoblotting. Total proteins were analyzed for the O-GlcNAc modification by immunoblot. QRT-PCR results in A–C are a calculated mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, n = 3. Immunoblots are a representative example from at least three independent experiments.

OGT Is Required for NF-κB Transcriptional Activity.

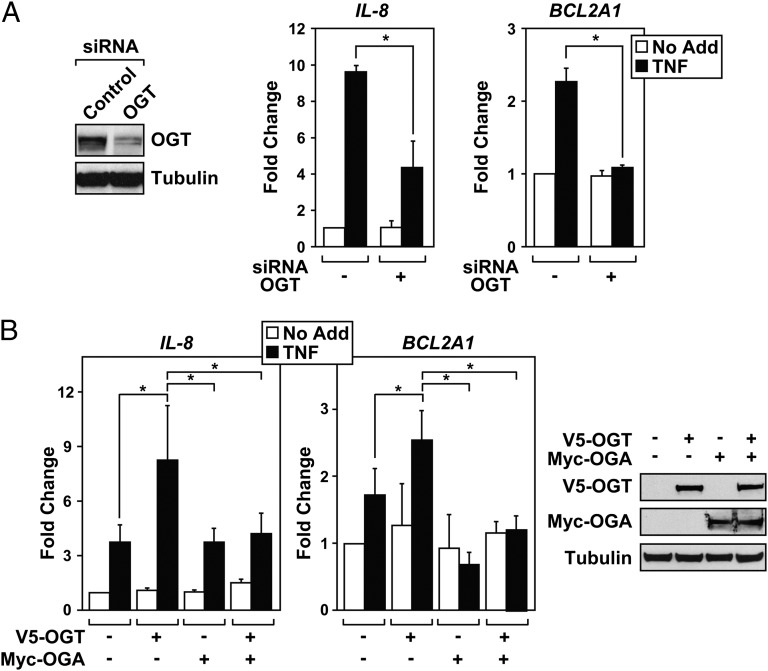

To determine whether OGT positively regulates NF-κB transcription, we first confirmed that cells transfected with OGT siRNA displayed a significant knockdown of the OGT protein (Fig. 2A). HEK 293T cells transfected with siRNA targeting OGT displayed reduced levels of IL-8 and BCL2A1 compared with cells transfected with control siRNA. Because the O-GlcNAc modification is dynamic and reversible, we tested whether ectopic expression of Myc-O-GlcNAcase (OGA) or V5-OGT altered NF-κB transcriptional activity. Exogenously expressed OGT increased transcription of IL-8 and BCL2A1 after TNF stimulation in HEK 293T cells (Fig. 2B). Additionally, ectopic expression of OGA effectively dampened the enhanced transcription of IL-8 and BCL2A1 observed from exogenous OGT expression. Immunoblots confirm V5-tagged OGT and Myc-tagged OGA expression. These results indicate that OGT protein expression is required for endogenous NF-κB transcription, linking the attachment of the O-GlcNAc moiety with inducible NF-κB transcription.

Fig. 2.

NF-κB transcription requires OGT. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with siRNA targeting either OGT or nonspecific control. After knockdown, protein levels of OGT were analyzed by immunoblot (Left), using α-tubulin as a loading control. HEK 293T cells were subjected to OGT knockdown, serum starved overnight, and treated with TNF (1 ng/mL) for 4 h. Expression of IL-8 or BCL2A1 was quantified by QRT-PCR (Right), and samples were normalized to GAPDH levels. Expression is represented as fold change compared with the unstimulated control knockdown. (B) OGT and OGA were transfected into HEK 293T cells alone or in tandem. After transfection, cells were treated with TNF (1 ng/mL) for 4 h. Expression of IL-8 or BCL2A1 expression was quantified by QRT-PCR (Left). Represented fold change values are compared with the unstimulated vector control. Immunoblots confirm the expression of V5-tagged OGT and Myc-tagged OGA (Right), compared with the α-tubulin loading control. Data are a calculated mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, n = 3.

Chromatin-Associated OGT Is Required for RelA Acetylation on NF-κB Regulated Promoters.

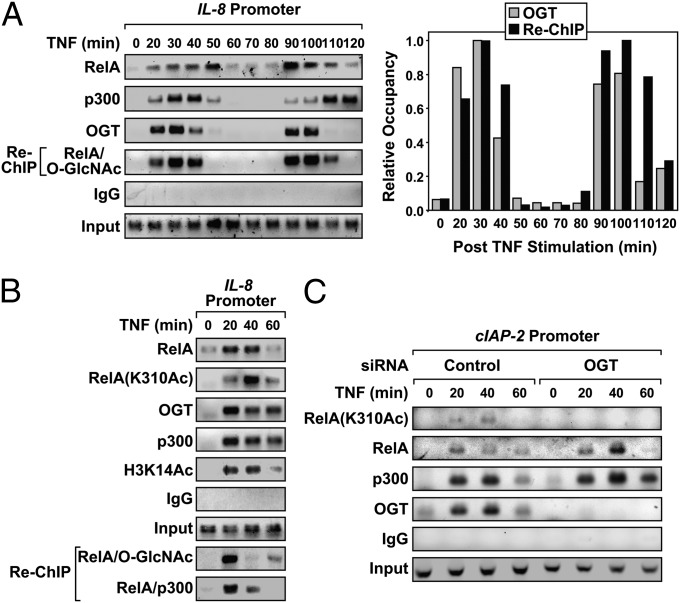

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed to ascertain whether OGT colocalizes with RelA on NF-κB regulated promoters. Similar to our previous report (23), TNF stimulation of DU145 cells results in the biphasic recruitment of RelA (20–50 and 90–120 min) to the IL-8 promoter. OGT was recruited to the IL-8 promoter in a stimulus-dependent manner and was present at the promoter over the same timeframe as both RelA and p300 (Fig. 3A). Re-ChIP experiments on the IL-8 promoter confirmed that RelA-bound complexes also contained increased levels of the O-GlcNAc modification. The relative IL-8 promoter occupancies of OGT and O-GlcNAcylated RelA were shown to have similar chromatin-associated patterns across the 120-min timeframe (Fig. 3A, Right).

Fig. 3.

NF-κB–regulated promoters require OGT for RelA acetylation. (A) DU145 cells were treated with TNF (10 ng/mL) over a 2-h time course, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and Re-ChIP assays were performed. Control IgG antibody was used as a negative IP control, and inputs served as a loading control. The relative IL-8 promoter occupancy was determined after normalization to the maximum level of chromatin-bound OGT or RelA/O-GlcNAc Re-ChIP complexes arbitrarily adjusted to one (Right). (B) DU145 cells were treated with TNF and subjected to ChIP and Re-ChIP with the indicated antibodies. (C) DU145 cells transfected with siRNA targeting either OGT or control were treated with TNF and ChIP was performed. Data are a representative example from at least three independent experiments.

Next, experiments were undertaken to determine whether recruitment of OGT to chromatin corresponded with elevated RelA(K310) acetylation. Consistent with Fig. 3A, RelA, p300, and OGT colocalized to the IL-8 promoter with similar kinetics (Fig. 3B). Moreover, OGT and acetylated RelA(K310) appear localized to the IL-8 promoter over the same timeframe. Specificity of the anti-RelA(K310Ac) antibody was confirmed in Fig. S2. The appearance of acetylated histone H3 Lys-14 (H3K14Ac) on the IL-8 promoter indicates active transcription during OGT and RelA(K310Ac) occupancy (Fig. 3B). Next, knockdown experiments were used to confirm the role of OGT in p300-driven acetylation of RelA on the promoter. As expected, knockdown of OGT significantly reduced the level of OGT recruited to chromatin after TNF stimulation (Fig. 3C). Although the loss of OGT expression had no effect on recruitment of either RelA or p300 to the cIAP-2 promoter, it ablated RelA(K310) acetylation. In fact, in the absence of OGT, p300 remained loaded on the cIAP-2 promoter with longer kinetics despite the lack of RelA acetylation. Results shown in Fig. 3 suggest that the recruitment of OGT to NF-κB–regulated promoters is required for p300-mediated acetylation of RelA in response to TNF stimulation.

O-GlcNAc Modification Enhances RelA Acetylation.

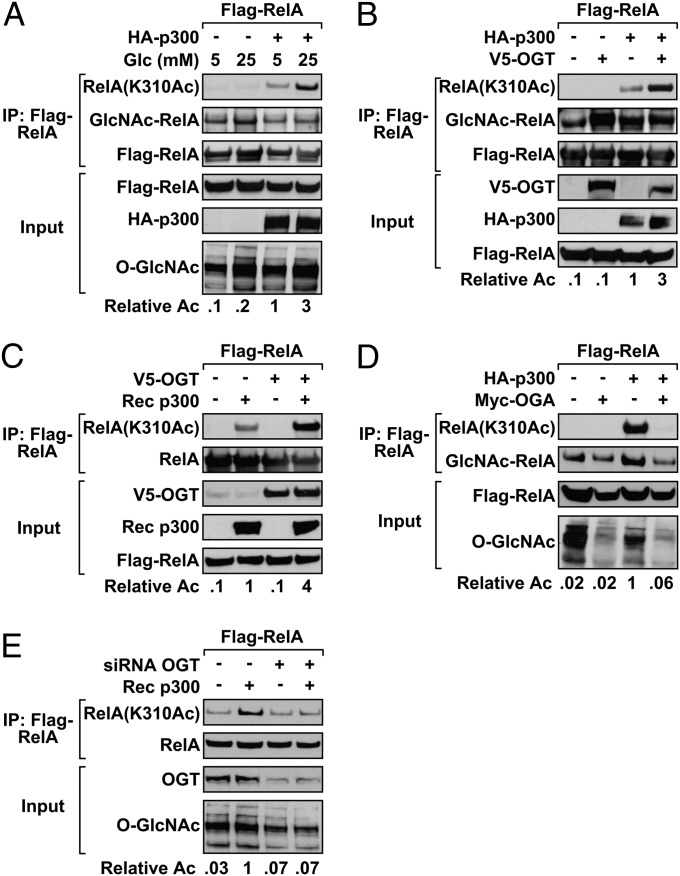

Because OGT knockdown ablated RelA(K310Ac) occupancy to the IL-8 promoter, we wanted to examine whether RelA acetylation was sensitive to changes in glucose concentration. Expression of p300 in HEK 293T cells effectively acetylates RelA as detected by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with the anti-RelA(K310Ac) antibody (Fig. 4A). Cells cultured in high glucose showed more robust p300-directed acetylation of RelA compared with cells grown in 5 mM glucose. Moreover, cells cultured in high glucose displayed an overall increase in total cellular O-GlcNAcylated protein. We then wanted to determine whether OGT potentiated acetylation of RelA. Analysis of immunoprecipitated RelA reveals that expression of ectopic V5-OGT robustly increased HA-p300–driven RelA(K310) acetylation (Fig. 4B). Further, the increase in RelA acetylation corresponded with a concomitant elevation in O-GlcNAcylated RelA without altering expression of either RelA or p300.

Fig. 4.

RelA acetylation is regulated by the O-GlcNAc modification. (A) The Flag-RelA expression plasmid was transfected into HEK 293T cells either alone or with HA-p300. After an overnight incubation in DMEM containing either 5 mM or 25 mM glucose, Flag-RelA was immunoprecipitated. O-GlcNAc modified RelA, and RelA(K310Ac) was subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) HEK 293T cells cotransfected with Flag-RelA, HA-p300, and V5-OGT were subjected to Flag immunoprecipitation. O-GlcNAc modified RelA and acetylated RelA were detected by immunoblotting. (C) HEK 293T cells were transfected with Flag-RelA and V5-OGT or with Flag-RelA alone. After Flag IP, RelA was acetylated with recombinant (Rec) p300 in vitro. RelA(K310) acetylation levels were analyzed by immunoblot. (D) HEK 293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-RelA and HA-p300 in the presence or absence of Myc-OGA. O-GlcNAc modified and RelA(K310Ac) were detected by IP. (E) After knockdown of OGT, HEK 293T cells were transfected with Flag-RelA. Flag IPs were subjected to in vitro acetylation with recombinant p300. Immunoblots were analyzed with RelA(AcK310Ac) antibody. Data are a representative example from three independent experiments, and densitometry results indicate the relative change in RelA(K310) acetylation where values were normalized to Flag-RelA inputs.

To clarify whether O-GlcNAc-modified RelA is a direct substrate for p300, in vitro acetylation assays were performed. Immunoprecipitated protein, isolated from cells transfected with Flag-RelA alone or with both Flag-RelA and V5-OGT, was incubated with recombinant p300. Flag-RelA isolated from cells cotransfected with V5-OGT was acetylated by recombinant p300 more effectively than cells transfected with Flag-RelA alone (Fig. 4C). The expression of Myc-OGA or the knockdown of OGT conversely reduced levels of Flag-RelA K310 acetylation (Fig. 4 D and E). These results are consistent with our findings that O-GlcNAc–modified RelA is required for p300 to acetylate RelA(K310).

RelA(T305) Is Required for p300-Mediated Acetylation.

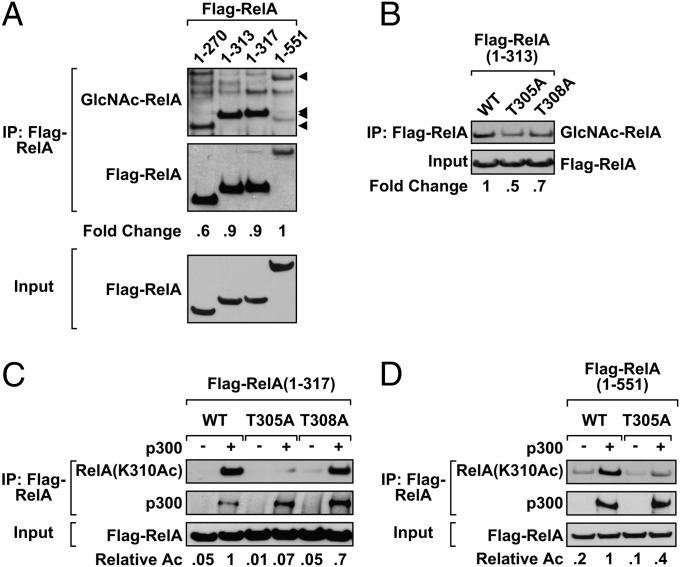

Although a previous report describes multiple O-GlcNAc modifications on RelA, this event was not associated with stimulus-driven activation of NF-κB (15). Therefore, we were interested in identifying O-GlcNAc–modified S/T residues within RelA associated with active transcription. Because RelA was shown to be modified at T322 and T352 by O-GlcNAc (15), we focused on RelA sequences near K310 to exclude sequences beyond T322. The full-length RelA, as well as RelA(1-313) and RelA(1-317) proteins, displayed similar levels of the O-GlcNAc modification relative to the amount of immunoprecipitated Flag-RelA (Fig. 5A). The reduced level of immunoprecipitated full-length RelA observed in Fig. 5A is consistent with a previously reported steric hindrance within the transactivation domain (33, 34). Compared with RelA(1-313), the RelA(1-276) protein showed a significant decrease in the O-GlcNAc modification, suggesting that the major O-GlcNAc sites were between residues 276 and 313. Because this region encompasses part of the Rel homology domain (276-304) required for contact with p50 (33, 35, 36), we examined S/T residues outside of this region. We investigated T305 and T308 as possible residues for O-GlcNAc modification based on their relative location to K310. Immunoprecipitated Flag-RelA mutants (T305A and T308A) displayed reduced levels of the O-GlcNAc modification compared with wild-type RelA(1-313) (Fig. 5B). Next, acetylation assays were performed. Wild-type RelA(1-317) and mutant RelA(T308A) proteins were robustly acetylated by p300 at K310 (Fig. 5C). However, site-directed mutagenesis of T305 on Flag-RelA(1-317) and Flag-RelA(1-551) abolished the ability of p300 to acetylate K310 without affecting RelA–p300 interaction. Thus, mutation of a single amino acid within the full-length RelA(T305A) significantly reduces O-GlcNAcylated protein and abolishes K310 acetylation.

Fig. 5.

O-GlcNAc modification of RelA is detected between residues 277–313. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with the indicated Flag-RelA construct (1–270, 1–313, 1–317, or 1–551) and incubated overnight with PugNAc (100 μM). O-GlcNAc modified RelA was subsequently detected by Flag IP. Arrows indicate the relative location of the Flag-RelA proteins. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with a Flag-RelA 1–313 construct containing either a T305A or T308A mutation. O-GlcNAc modified RelA was detected by Flag IP. (C) Flag-RelA 1–317 mutants were expressed in HEK 293T cells. After Flag IP, RelA was acetylated in vitro with recombinant p300. RelA(K310Ac) was analyzed by immunoblot. (D) Wild-type and T305A Flag-RelA was expressed in HEK 293T cells. HEK 293T cells were transfected with full-length Flag-RelA (WT or T305A). After Flag IP, RelA was acetylated in vitro by using recombinant p300, and the samples were assayed for K310 acetylation by immunoblot. Data are a representative example from three independent experiments. Band densities of O-GlcNAc modified RelA (A and B) and RelA(K310Ac) (C and D) are shown relative to the levels observed for the wild-type Flag-RelA protein. Densitometry analysis is normalized to Flag-RelA inputs.

RelA(T305) Is Essential for NF-κB–Mediated Cell Survival.

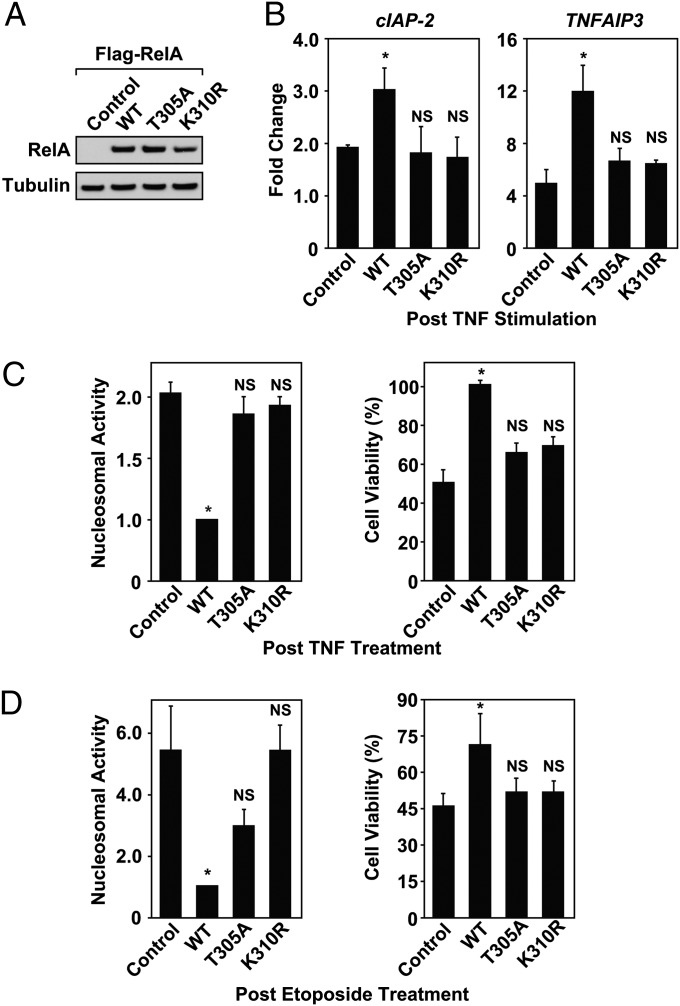

Cell survival is one of the best characterized pathways regulated by NF-κB gene products (37–39). The ability of stimuli to activate NF-κB prosurvival genes overcomes TNF- and etoposide-induced apoptosis (40, 41). To determine the importance of T305 for RelA-dependent transcription and cell survival, RelA−/− MEFs were stably reconstituted with wild-type or mutant Flag-RelA (T305A or K310R). Stable subclones expressed similar levels of wild-type and mutant RelA proteins (Fig. 6A). As expected, the introduction of wild-type RelA into MEFRelA−/− cells restored TNF-induced NF-κB expression of cIAP-2 and TNFIAP3 compared with MEFRelA−/− vector control cells (Fig. 6B). However, reintroduction of either RelA(T305A) or RelA(K310R) into MEFRelA−/− cells failed to rescue NF-κB–mediated transcription after TNF stimulation (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that the inability of RelA to be modified by O-GlcNAc at T305 significantly inhibits NF-κB transcription in a manner similar to cells expressing the nonacetylated mutant RelA(K310R). Additionally, MEFRelA−/− cells expressing either RelA(T305A) or RelA(K310R) remained sensitive to TNF- and etoposide-induced cell death as determined by elevated nucleosomal fragmentation and a loss of cell viability (Fig. 6 C and D). Collectively, our data indicate that MEFRelA−/− cells expressing RelA(T305A) are deficient for NF-κB transcription and, as a result, remain more sensitive to TNF- and etoposide-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

NF-κB–mediated cell survival depends on T305. (A) Expression levels of Flag-RelA were assessed in reconstituted RelA−/− MEFs by immunoblot. (B) After overnight serum starvation, reconstituted RelA−/− MEFs were treated with TNF (1 ng/mL) for 2 h. Expression of cIAP-2 and TNFAIP3 was analyzed by QRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH levels. Fold change is displayed relative to the untreated RelA−/− MEF control cell line. (C and D) Reconstituted RelA−/− MEFs were serum starved overnight and treated with either TNF (10 ng/mL) for 8 h or etoposide (50 μM) for ten hours. After treatment, the cells were assayed for nucleosomal fragmentation by using the cell death ELISA or viability using trypan blue exclusion. Nucleosomal activity and cell viabilities are displayed relative to RelA−/− MEFs reconstituted with wild-type Flag-p65. QRT-PCR, apoptosis, and cell viability results are a calculated mean ± SD; NS, not significant compared with controls; *P < 0.05, n = 3.

Discussion

Regulation of RelA Transcriptional Activity by the O-GlcNAc Modification.

Previous studies provide evidence that the HBP pathway and OGT regulate NF-κB transcription through two distinct mechanisms: one in which OGT enhances the catalytic activity of IKKβ and another that regulates nuclear accumulation of RelA under basal conditions (12, 15). Additional reports demonstrate that B and T cells use OGT to fully activate NF-κB transcription, which corresponds with increased O-GlcNAcylated RelA (11). Although these studies provide insight into the requirement of OGT for activation of NF-κB–dependent gene expression, the molecular mechanism by which O-GlcNAc drives RelA transcription remains elusive. Here, we provide evidence that addition of the O-GlcNAc modification on RelA promotes NF-κB transcription by potentiating p300-dependent acetylation on K310 (Fig. S3). Several laboratories including our own have demonstrated the importance of RelA(K310) acetylation for active NF-κB transcription (25, 30, 31). This observation is further supported by recent evidence that monomethylation of RelA(K310me1) acts as an antagonistic modification to repress NF-κB transcription (42). Thus, posttranslational modifications that regulate the acetylation or methylation status of RelA(K310) have a significant impact on cellular processes regulated by NF-κB gene products.

After TNF stimulation, we find that OGT localizes to chromatin and p300-mediated acetylation of RelA K310 requires the O-GlcNAc modification. Moreover, our studies identify RelA(T305) as the major site required for O-GlcNAcylation. The proximity of RelA(T305) to the major activating acetylation site, K310, suggests coordinated regulation between OGT and p300. Interestingly, an alignment of histones with nonhistone p300 substrates (43) identifies several transcription factors that contain S/T five residues from known p300 acetylation sites, including c-Myb, p53, p73, and androgen receptor. Therefore, the O-GlcNAc modification may act as a prerequisite cue for p300/CBP-dependent acetylation of multiple transcription factors.

RelA(T305) as a Site of O-GlcNAc Regulation.

Site-directed mutagenesis of T305 reduced levels of O-GlcNAc–modified RelA. Although RelA possesses multiple sites of O-GlcNAcylation, T305 is evolutionally conserved from Homo sapiens to Xenopus (Fig. S4). RelA(T305) resides within α-helix four, a segment essential for high-affinity binding of IκBα to NF-κB (33, 35, 36). In unstimulated cells, IκBα binds to the RelA through α-helix four, creating a tight interaction that would prevent access to cytosolic OGT. Therefore, the unique location of T305 ensures that canonical signaling through the IKK complex is required to stimulate IκBα degradation, NF-κB nuclear translocation, and chromatin occupancy before OGT gains access to RelA—a model that is supported by our work. Thus, the degradation of IκBα not only liberates RelA for nuclear translocation, but also ensures chromatin-associated OGT access to T305. Together, our findings indicate that the O-GlcNAc modification plays a key role in NF-κB activation by promoting RelA acetylation on chromatin.

Relationship Between OGT and Transcriptional Regulation.

To date, OGT has been shown to interact with at least 10 chromatin-associated complexes that either activate or repress target genes (3, 7, 8, 10, 44, 45). In terms of gene induction, OGT resides in the Set1/Ash1/MLLL histone H3K4 methyltransferase complex. The H3K4 modification is one of the most important histone marks associated with transcriptional activation (46, 47).

Using RelA, as a HBP-responsive transcription factor, we provide evidence that OGT is required for p300-mediated acetylation of chromatin-associated RelA. Our study suggests that the O-GlcNAc modification on RelA specifies it as a preferred target for p300 acetylation. Moreover, the knockdown of OGT not only dampens p300-dependent acetylation of RelA K310, but it also down-regulates p300 autoacetylation at K1499 without impacting p300 interaction with RelA (Fig. S5). Thus, future work is needed to determine whether p300/CBP contain domains that specifically recognize O-GlcNAc–modified transcription factors and whether this event is required to further potentiate acetyltransferase activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents.

HEK 293T and DU145 cells were obtained from ATCC. RelA−/− MEFs were kindly provided by Denis Guttridge (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) with permission from Amer Beg (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL). Cells were cultured as described (21, 23, 25). For 5 mM glucose treatments, cells were incubated overnight in DMEM containing 1 g/L glucose (CellGro; 10–014-CV), and dialyzed FBS (Gibco; 26400–036). Glcn treatment lasted 4 h after overnight incubation in 5 mM glucose. Reagents purchased were as follows: TNF (Invitrogen, PHC3016), PugNAc (Toronto Research Chemicals), and Glcn and etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich). Antibodies were as follows: M2-Flag, M2-Flag Agarose, α-tubulin, and OGT (Sigma; F1804, A2220, T9026, O6139); RelA, p105, IκBα, HDAC1, normal mouse IgG, and normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz; sc-372, sc-1191, sc-371, sc-7872, sc-2025, sc-2027); ChIP grade RelA and p300 (Millipore; AB1604, 05–257); RelA(K310Ac) (Cell Signaling; 3045); H3K14Ac and RNA polymerase II (Active Motif; 39599, 39097); V5 (Invitrogen, R960-025); HA (Covance; MMS-101P); anti-mouse HRP and anti-rabbit HRP (Promega; W4021, W4011); anti-mouse IgM (Bethyl, A90-101P). O-GlcNAc (CTD110.6) was provided by G.W.H.

Plasmid Constructs.

Full-length cDNA OGT (Origene; TC124260) was used as a template and subcloned into V5-His pCDNA3.1 (Invitrogen; V810-20). The Myc-tagged OGA plasmid was provided by G.W.H. pBabe-Puro was kindly provided by R. A. Weinberg (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA). The Flag-RelA, HA-p300, β-Galactosidase, and the 3×-κB-luciferase reporter were described (25). Plasmid mutagenesis was performed by using the QuikChange II XL Site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

Transfections, Luciferase Assays, QRT-PCR, and ChIP Assays.

Plasmid and siRNA transfections and luciferase assays were performed as described (25). QRT-PCR experiments were carried out as described (48). PCR primers are shown in Table S1. ChIP and Re-ChIP experiments were carried out as described (21).

Immunoprecipitation, Acetylation Assays, and Immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation, acetylation assays, and immunoblotting were performed as described (21, 23, 25). In vitro acetylation assays were carried out by using recombinant full-length p300 (ProteinOne; 2004–01) and the HAT assay kit (Millipore; 17–289). To detect O-GlcNAc modified RelA, transfected HEK 293T cells were incubated overnight with PugNAc (100 μM) and Flag IP RelA proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Creation of Retrovirus and Stable Cell Lines.

Retroviruses encoding pBabe-Puro RelA and mutant RelA were generated. The RelA−/− MEFS were grown to subconfluency and infected as described (25). Forty-eight hours after infection, 1.5 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma) was added for selection. Colonies were isolated and expression of RelA was confirmed via immunoblotting.

Cell Death ELISA and Cell Viability Assay.

The RelA−/− MEF cell lines stably expressing various constructs were treated for 8 h with 10 ng/mL TNF or for 10 h with 50 μM etoposide. After treatment, cell death ELISA (Roche; 11774425001) or cell viability assay was carried out by using trypan blue exclusion.

Statistics.

Fold changes were log2 transformed, and a one-tailed Student t test was performed by using Microsoft Excel. Data for all experiments were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. A. Sherman for editorial assistance. Work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants R01CA132580, R01CA104397 (to M.W.M.), R01CA136705 (to D.R.J.), R01DK61671, and P01HL107153 (to G.W.H.). In addition, both M.W.M and D.R.J. were supported, in part, by independent awards provided to the University of Virginia by Philip Morris USA through an external review process.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1208468109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dennis JW, Nabi IR, Demetriou M. Metabolism, cell surface organization, and disease. Cell. 2009;139:1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wellen KE, et al. The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway couples growth factor-induced glutamine uptake to glucose metabolism. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2784–2799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1985910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanover JA, Krause MW, Love DC. The hexosamine signaling pathway: O-GlcNAc cycling in feast or famine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: Roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:825–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shafi R, et al. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5735–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100471497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang YR, et al. O-GlcNAcase is essential for embryonic development and maintenance of genomic stability. Aging Cell. 2012;11:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanover JA, Krause MW, Love DC. Bittersweet memories: Linking metabolism to epigenetics through O-GlcNAcylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:312–321. doi: 10.1038/nrm3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Love DC, Krause MW, Hanover JA. O-GlcNAc cycling: Emerging roles in development and epigenetics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. A little bit of sugar makes polycomb better. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:11–12. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slawson C, Hart GW. O-GlcNAc signalling: Implications for cancer cell biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:678–684. doi: 10.1038/nrc3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golks A, Tran TT, Goetschy JF, Guerini D. Requirement for O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase in lymphocytes activation. EMBO J. 2007;26:4368–4379. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawauchi K, Araki K, Tobiume K, Tanaka N. Loss of p53 enhances catalytic activity of IKKbeta through O-linked beta-N-acetyl glucosamine modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3431–3436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813210106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozcan S, Andrali SS, Cantrell JE. Modulation of transcription factor function by O-GlcNAc modification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing D, et al. O-GlcNAc modification of NFκB p65 inhibits TNF-α-induced inflammatory mediator expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang WH, et al. NFkappaB activation is associated with its O-GlcNAcylation state under hyperglycemic conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806198105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebel AL, Fernandez AZ, El-Osta A. Glycemic memory associated epigenetic changes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1853–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SK, Kim JH, Lee YC, Cheong J, Lee JW. Silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors, as a novel transcriptional corepressor molecule of activating protein-1, nuclear factor-kappaB, and serum response factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12470–12474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baek SH, et al. Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-kappaB and beta-amyloid precursor protein. Cell. 2002;110:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S. The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF-kappa B determines its association with CBP/p300 or HDAC-1. Mol Cell. 2002;9:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoberg JE, Yeung F, Mayo MW. SMRT derepression by the IkappaB kinase alpha: A prerequisite to NF-kappaB transcription and survival. Mol Cell. 2004;16:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashburner BP, Westerheide SD, Baldwin AS., Jr The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-kappaB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7065–7077. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7065-7077.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoberg JE, Popko AE, Ramsey CS, Mayo MW. IkappaB kinase alpha-mediated derepression of SMRT potentiates acetylation of RelA/p65 by p300. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:457–471. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.457-471.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawahara TL, et al. SIRT6 links histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylation to NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression and organismal life span. Cell. 2009;136:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeung F, et al. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369–2380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerritsen ME, et al. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheppard KA, et al. Nuclear integration of glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by CREB-binding protein and steroid receptor coactivator-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29291–29294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paal K, Baeuerle PA, Schmitz ML. Basal transcription factors TBP and TFIIB and the viral coactivator E1A 13S bind with distinct affinities and kinetics to the transactivation domain of NF-kappaB p65. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1050–1055. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz ML, Stelzer G, Altmann H, Meisterernst M, Baeuerle PA. Interaction of the COOH-terminal transactivation domain of p65 NF-kappa B with TATA-binding protein, transcription factor IIB, and coactivators. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7219–7226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buerki C, et al. Functional relevance of novel p300-mediated lysine 314 and 315 acetylation of RelA/p65. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1665–1680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen LF, Mu Y, Greene WC. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 2002;21:6539–6548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothgiesser KM, Fey M, Hottiger MO. Acetylation of p65 at lysine 314 is important for late NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huxford T, Huang DB, Malek S, Ghosh G. The crystal structure of the IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-kappaB inactivation. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergqvist S, et al. Thermodynamics reveal that helix four in the NLS of NF-kappaB p65 anchors IkappaBalpha, forming a very stable complex. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beg AA, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: Potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB antiapoptosis: Induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang CY, Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB induces expression of the Bcl-2 homologue A1/Bfl-1 to preferentially suppress chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5923–5929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy D, et al. Lysine methylation of the NF-κB subunit RelA by SETD6 couples activity of the histone methyltransferase GLP at chromatin to tonic repression of NF-κB signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:29–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, et al. The structural basis of protein acetylation by the p300/CBP transcriptional coactivator. Nature. 2008;451:846–850. doi: 10.1038/nature06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dey A, et al. Loss of the tumor suppressor BAP1 causes myeloid transformation. Science. 2012;337:1541–1546. doi: 10.1126/science.1221711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruan HB, et al. O-GlcNAc Transferase/Host cell factor C1 complex regulates gluconeogenesis by modulating PGC-1alpha stability. Cell Metab. 2012;16:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wysocka J, Myers MP, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Herr W. Human Sin3 deacetylase and trithorax-related Set1/Ash2 histone H3-K4 methyltransferase are tethered together selectively by the cell-proliferation factor HCF-1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:896–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujiki R, et al. GlcNAcylation of a histone methyltransferase in retinoic-acid-induced granulopoiesis. Nature. 2009;459:455–459. doi: 10.1038/nature07954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramsey CS, et al. Copine-I represses NF-kappaB transcription by endoproteolysis of p65. Oncogene. 2008;27:3516–3526. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.