Abstract

The heptameric mechanosensitive channel of small conductance (MscS) provides a critical function in Escherichia coli where it opens in response to increased bilayer tension. Three approaches have defined different closed and open structures of the channel, resulting in mutually incompatible models of gating. We have attached spin labels to cysteine mutants on key secondary structural elements specifically chosen to discriminate between the competing models. The resulting pulsed electron–electron double resonance (PELDOR) spectra matched predicted distance distributions for the open crystal structure of MscS. The fit for the predictions by structural models of MscS derived by other techniques was not convincing. The assignment of MscS as open in detergent by PELDOR was unexpected but is supported by two crystal structures of spin-labeled MscS. PELDOR is therefore shown to be a powerful experimental tool to interrogate the conformation of transmembrane regions of integral membrane proteins.

Keywords: DEER, electron paramagenetic resonance, ion channels, dipolar coupling

Membranes provide an impermeable barrier to the flow of polar molecules and are a defining characteristic of cellular organisms. All organisms must permit passage of polar molecules into and out of the cell, and membrane proteins, such as channels and transporters, achieve this. The opening and closing (gating) of these proteins is often regulated. Mechanosensitive ion channels act as safety valves to protect bacterial cells against hypoosmotic shock by gating in response to increased tension in the membrane bilayer that arise from increases in turgor pressure (1). These channels have proved to be an excellent model to study channel gating. The two major mechanosensitive channels, mechanosensitive channel of small conductance (MscS) and mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL), are the most well-studied.

Native MscS crystallized from Fos-14 detergent exists as a heptamer (2) with each monomer consisting of three N-terminal transmembrane helices (TM1, TM2, TM3 in which TM3 is split by a kink at Q112-G113 into TM3a, and TM3b) and a large cytoplasmic domain, which is composed of a β domain, a mixed α/β domain, and a β strand (Fig. 1A). The sevenfold symmetry generates a central pore formed by TM3a, with TM3b arranged orthogonally and pointing outward from the pore (Fig. 1B). The central pore is the presumed route of entry and exit for polar molecules and in the native structure is now considered closed (diameter approximately 4 Å) by two rings of L105 and L109, which intrude into the channel (2–4). An A106V mutant (5) also crystallized from Fos-14 gave a structure in which the central pore had opened to approximately 13 Å in a “camera iris”-like motion (6). The C-terminus of TM3a had pivoted at G113 and as result L105 and L109 were withdrawn from the central pore. The pivot of TM3a was accompanied by a rotation of TM1 and TM2 helices. Combining the crystal structures with site directed mutagenesis, a model was proposed in which TM1 and TM2 act as sensors and rotate in response to changes in the membrane tension driving change in TM3a(6).

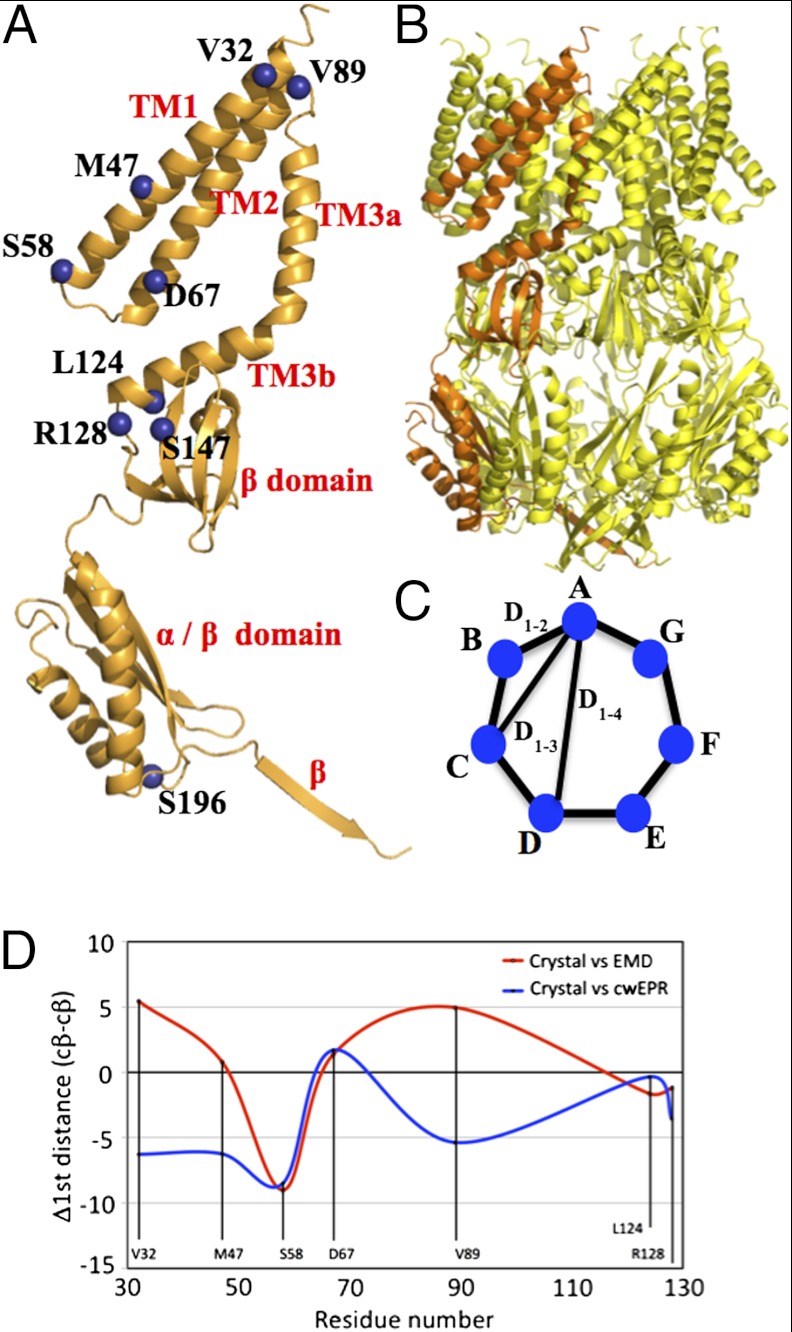

Fig. 1.

MscS and PELDOR. (A) A monomer of MscS showing where spin labels have been attached (blue spheres). (B) The heptameric arrangement of MscS, one monomer is highlighted. (C) In principle a heptamer gives rises to three distances, which are shown as vectors. We expect to see only the D1–2 and D1–3 vectors in our PELDOR experiments, with the D1–2 vector being the most reliable. (D) The difference between the D1–2 vector measured from the Cβ atom in the open crystal structure (PDB ID code 2VV5) and the EMD structure (red) or cwEPR (blue). Similar plots are shown in Fig. S1A (closed crystal structure vs. EMD or cwEPR) and Fig. S1B (closed vs. open crystal structure).

Very different models for both the closed and open forms of the channel, and thus gating, have been generated using extrapolated motion dynamics (EMD) (7) and continuous wave electron paramagenetic resonance (cwEPR) (8, 9). As a result, the validity of the channel gating model derived from crystallography has been repeatedly challenged (10, 11). While genetic and biochemical strategies have provided some insights into the validity of the competing models, they have not been decisive (12). There is in general paucity of new orthogonal methods to probe the conformation of transmembrane helices in proteins.

Controversies and competing models can rarely be resolved by continued application of the same techniques. Thus, we have sought to apply new strategies for understanding MscS structure and function. Pulsed electron–electron double resonance (PELDOR; also called DEER) (13) is established for soluble proteins and has been applied to many proteins from monomers to octamers (14, 15), to solvent exposed termini of transmembrane helices or loops that are embedded in lipid bilayers (16–19), to transmembrane helices (20, 21), and to 15 amino acid hydrophobic peptides in various lipid environments (22). Here we report the application of PELDOR to measure the separation of transmembrane structural elements in MscS in an attempt to experimentally resolve current disputes and thereby demonstrate the wider utility of PELDOR. Residues were chosen for their ability to act either as controls (all models agree on position) or to discriminate between competing models (i.e., are proposed to have different distances in the separate models). We now report measurements from spin labels attached to cysteine mutants placed within the membrane embedded regions of TM1, TM2, and TM3b in MscS (Fig. 1C). We demonstrate that carefully performed PELDOR experiments can obtain high-quality data that can be used to determine the separation of transmembrane helices even in a complex system. New crystal structures of two spin-labeled mutants of MscS are in complete agreement with the PELDOR data.

Results

Selection, Assessment, and Isolation of MscS Mutants.

Labeled sites were selected on the basis of their predicted distance distribution change between competing models, on their likelihood of causing minimal perturbation to the MscS function and their predicted accessibility to labeling. The variation of the separation between individual residues within helices is complex. A graph showing how the separation changes at each position is shown in Fig. 1D and Fig. S1A. This led us to select the following mutants: V32C, M47C, S58C on TM1, D67C, V89C on TM2 and L124C, and R128C on TM3b (Fig. S1B). In addition to the membrane embedded residues we selected two residues S147 and S196 in the cytosolic domain to act as controls because this domain is generally accepted (only one report has suggested movement) and predicted from crystal structures to undergo no major changes during the closed to open transition. For each MscS mutant, whole cell Western blots showed that each mutant was expressed and was incorporated into the membrane to a level indistinguishable from wild-type MscS. The whole cell survival assay revealed that each cysteine mutant was sufficiently functional to protect cells against osmotic downshock (Fig. S2A). Critically, the protection afforded by the uninduced constructs, which most accurately reflects the activity of the channels (23, 24), indicates that the mutants are similar in their physiological activity to native. Each mutant was assessed by electrophysiological analysis, and here differences were observed, consistent with some perturbation of gating (Fig. S2B). The pressure threshold required for gating the mutant channels was increased for S58C, D67C, L124C, and R128C, indicating an approximately 20% decrease in tension sensitivity. Both D67C and L124C exhibited some instability in the open state (Fig. S2B). For other mutants (M47C, V89C, S147C, and S196C), the channel properties were similar to wild type suggesting that these mutants do not significantly affect protein function. The V32C mutant exhibited a small gain of function—i.e., increased sensitivity to tension (Fig. S2B). Thus, while none of the mutants is wild type, the mutants’ overall character suggests that they retain channel function and gate in response to changes in bilayer tension and thus can be used as faithful reporters.

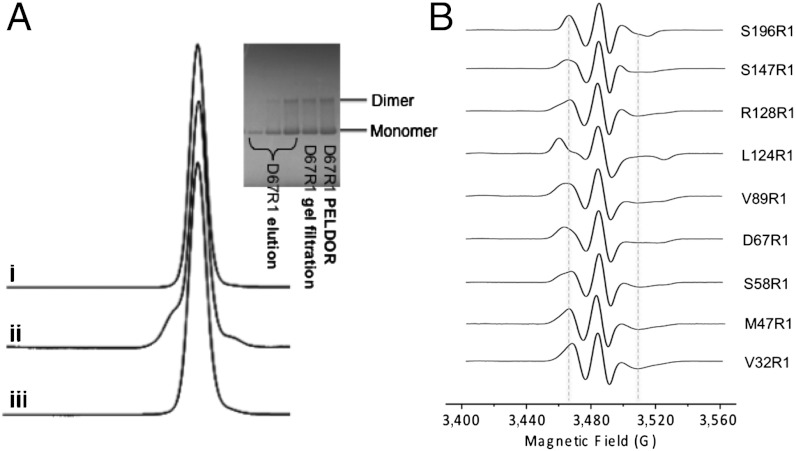

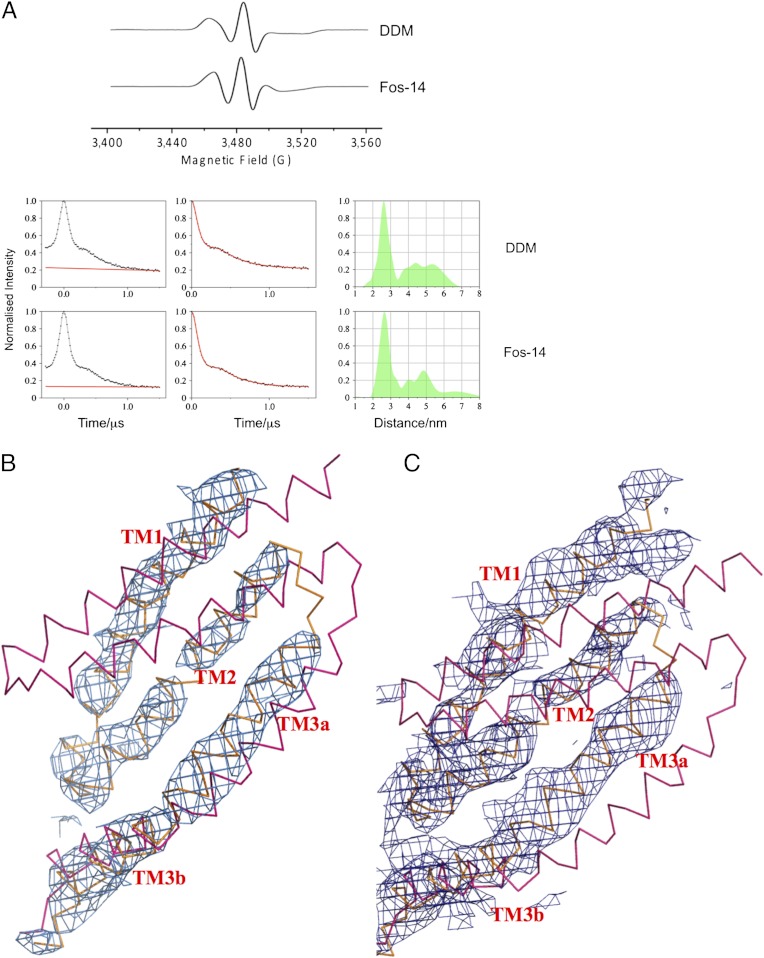

All MscS mutants were expressed and purified to homogeneity as previously reported (6) but with DDM rather than Fos-14 as detergent (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3). The mutants were labeled by incubation with MTSSL. We achieved close to 100% labeling for most of the mutants (Fig. S4), with the exception of L124C and M47C, which are situated in more inaccessible, buried regions of MscS and display a labeling efficiency of about 60–80%. Each labeled mutant behaved as a heptamer by gel filtration analysis (Fig. S3) before and after PELDOR measurements and purity was monitored in each individual step of the sample preparation (Fig. 2A). Mutant proteins with a spin label attached to an introduced cysteine are denoted D67R1 or S196R1 etc. cwEPR spectra were recorded, and fitting of the spectra revealed intermediate mobility with correlation times varying from 3 to 70 ns (Fig. 2B and Table S1 and Fig. S5A). V32R1 had the highest mobility and L124R1 the least.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of spin labeled mutants of MscS. (A) Gel filtration (left inset) shows the spin labeled material elutes as a single peak, corresponding to a detergent solubilized heptamer: (i) D67R1 prior to PELDOR experiment; (ii) D67R1 after having been used for PELDOR measurements; and (iii) WT MscS. SDS/PAGE (right inset) shows no contaminating protein, only monomer and disulfide linked dimer monitored on several preparation stages. The data for D67R1 are shown, the other mutants are identical (Fig. S3). (B) cwEPR spectra of the spin labeled MscS proteins. Fitting of the spectra (Fig. S5A and Table S1) suggests that for the L124R1 mutant, the spin label is less mobile than the other mutants.

PELDOR Measurement.

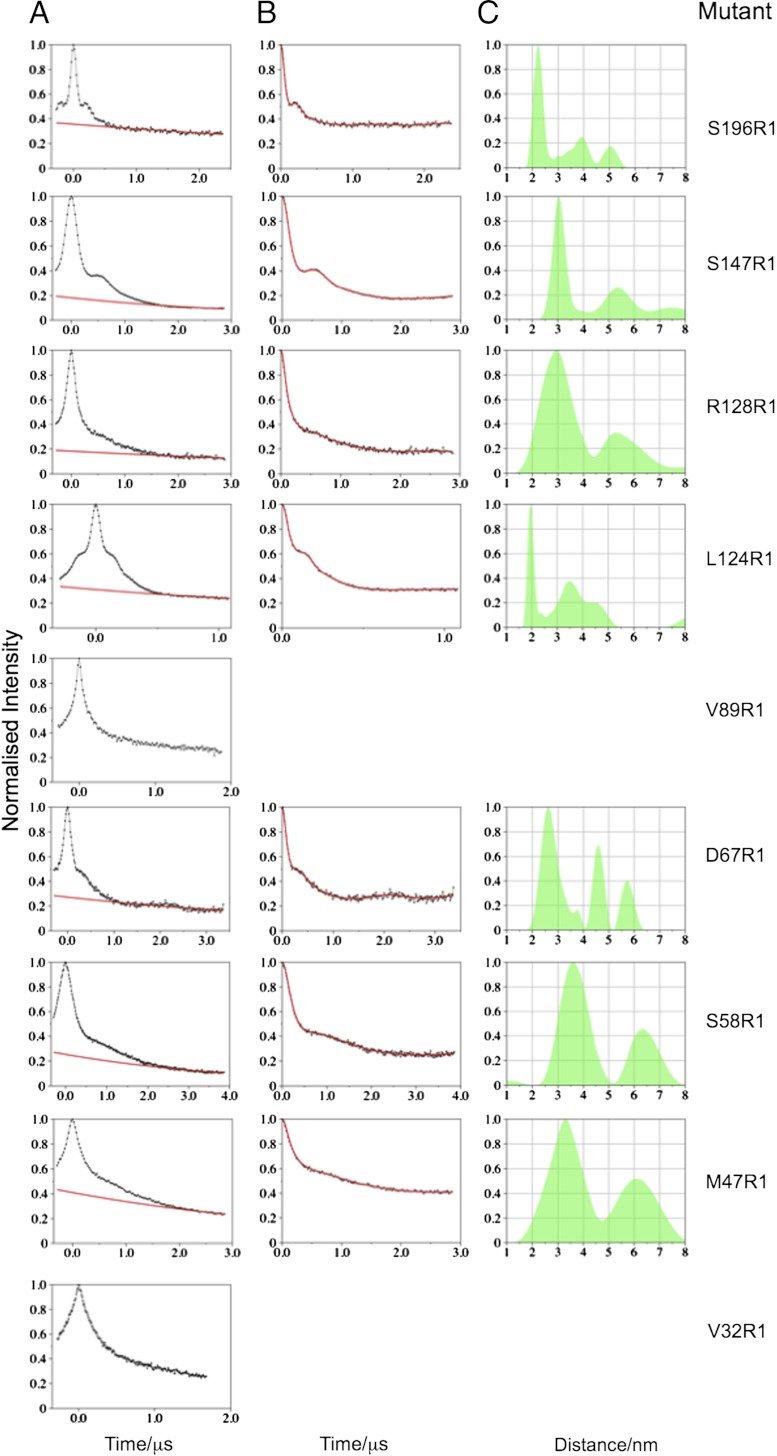

In the PELDOR experiment distances between labels are measured via the dipolar coupling, which manifests itself as a modulation of the signal. The dipolar interaction between labels on randomly distributed MscS heptamers gives rise to an exponential decay, which is fitted and removed from the time trace. Transformation of the modulated time trace into a distance distribution is done via Tikhonov regularization as implemented in DeerAnalysis 2010 (25). We excluded V32R1 and V89R1 from further analyses because they do not show clear modulations (Fig. 3A). Where no oscillations are visible in the raw data, the resulting distance distribution for multimeric protein systems can be biased by the operator (13). (Traces without oscillations may be sufficient for a reliable analysis of model systems (26). For multimeric proteins such as MscS this is not the case.) One explanation is that at these positions the protein structure is mobile, consistent with the observed mobility of the spin label revealed by their cwEPR spectra (Fig. 2B). The other seven mutants yielded time traces of several microseconds (Table S2), with good signal-to-noise ratios, clearly visible oscillations prior to background correction (Fig. 3A), and therefore distance distributions could be determined (Fig. 3 B and C). In theory each mutant should give rise to a multimodal distribution corresponding to the 1–2, 1–3, and 1–4 vectors (Fig. 1C). In agreement with previous work (14) the experimental error in 1–2 distance (spin to spin) is estimated to ± 0.5 Å, the 1–3 distance is subject to greater error, and the 1–4 distance is too long to be measured (discussed in more detail in Materials and Methods). Our interpretation thus relies only on the modal distance and distance distribution for the D1–2 vector. These experimental data were compared with modeled distance distributions (27) based on the various competing structural models for the arrangement of the transmembrane helices (2, 3, 6–9, 28; Fig. 4). D67R1 was repurified in Fos-14 detergent and as expected gave a different cwEPR spectrum reflecting change in environment (29), but PELDOR data were identical (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 3.

PELDOR data and distance distributions obtained for spin labeled MscS mutants. (A) Raw PELDOR data (black line and dots) and applied background correction (red line). (B) Background corrected PELDOR data (black line and dots) and the most appropriate simulated time trace (red line) based upon the L curve analysis (Fig. S7) implemented within DeerAnalysis2010. (C) Distance distribution (semi-transparent green shape).

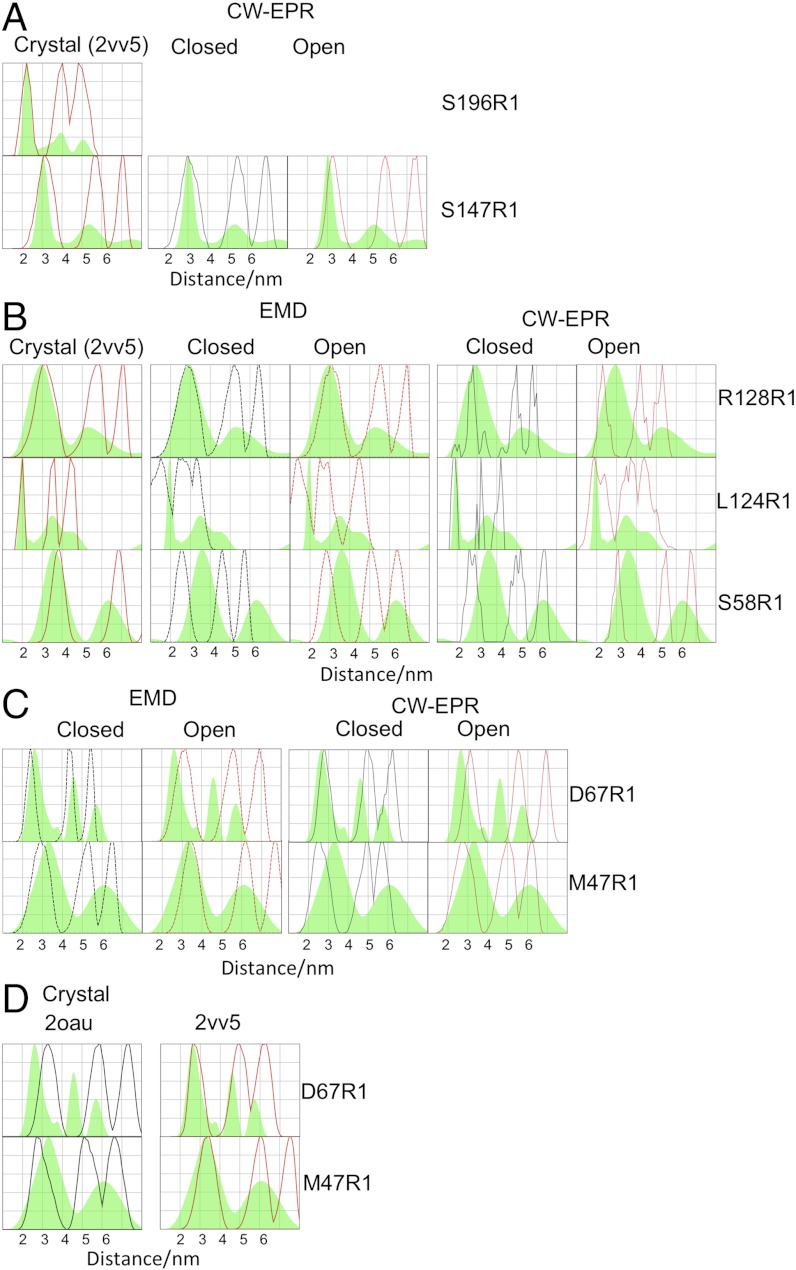

Fig. 4.

Comparison of experimental and model derived distance distributions. (A) Tikhonov derived distance distributions, for the two control mutants compared with the simulated distance distributions obtained from the higher resolution open crystal structure (PDB ID code 2VV5) (the closed crystal structure is identical in this region), closed or open structures obtained from cwEPR measurements. All models are shown for all mutants in Fig. S8. Our interpretation relies only on the D1–2 vector (first peak). (B) Tikhonov derived distance distributions for the three mutants designed to test the competing models compared with the simulated distance distributions open crystal structure (the closed crystal structure is identical in this region), closed and open EMD structures; closed and open structures obtained from cwEPR measurements. Our interpretation relies only on the D1–2 vector (first peak). (C) Tikhonov derived distance distributions, for the two mutants designed to interrogate the conformational state of MscS compared with the closed and open EMD structures and with the closed and open structures obtained from cwEPR measurements. Our interpretation relies only on the D1–2 vector (first peak). (D) Tikhonov derived distance distributions, for the two mutants designed to identify the conformational state of MscS compared with the closed crystal structure (PDB ID code 2OAU) and with the open crystal structure (PDB ID code 2VV5). Our interpretation relies only on the D1–2 vector (first peak).

Fig. 5.

MscS is open in solution. (A) PELDOR and cwEPR of D67R1 in DDM and in Fos-14. The spectra show profound differences in cwEPR but very similar PELDOR data and identical distance distribution. (B) Unbiased 2Fo-Fc contoured at 1σ difference electron density map (blue chicken wire) for the transmembrane helices of D67R1. The helices are shown from the open structure (orange) and closed structure (pink). Only the open structure is consistent with the density. (C) The same result is obtained for L124R1. The helices are shown in the open structure (orange) and closed structure (pink).

Structural Biology.

We have attempted to crystallize all mutants in this study and have obtained crystals for D67R1 and L124R1 grown from DDM that diffract to 4.8 and 4.7 Å resolution, respectively. Both structures were solved with molecular replacement using only the cytoplasmic domain as a search model (i.e., excluding all transmembrane helices). The resulting unbiased difference electron density for D67R1 (Fig. 5B) and L124R1 (Fig. 5C) for the transmembrane helices was used to position the helices.

Discussion

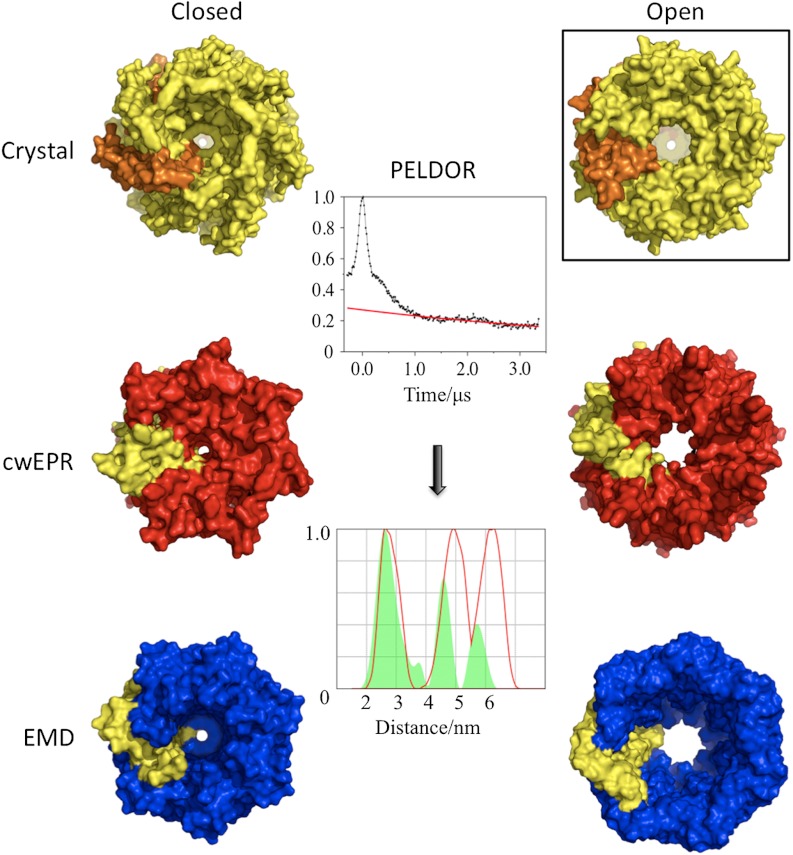

For MscS the closed and open crystal structures have been complemented by data from other groups using two alternative approaches—cwEPR and EMD. Of crucial importance is that three competing approaches crystallography, cwEPR and EMD have given biologists three mutually incompatible models of gating, to the detriment of the field (11, 12). In the EMD structure the kink at G113 between TM3a and TM3b seen in crystal structures (2, 3, 6) is absent; instead TM3a is a continuous helix to G121 where a new kink appears, creating a shorter TM3b (G121-R128) (7). Gating occurs by a change in packing of TM1-TM2 with TM3 in response to membrane tension, this removes the new (G121) kink, such that TM3a is now a single helix to R128 (30). This unkinking and consequent repacking of helices shifts the position of TM3a, opening the channel. In the crystal structures TM1/TM2 do not pack closely with TM3a, leaving a “wedge”-shaped void above TM3b (2, 3, 6). However, in both EMD structures a close packing arrangement of TM3a and TM1/TM2 is seen (7, 30). The existence of this wedge is adduced as evidence of the artifactual nature of both crystal structures that arises due to packing in a lattice (10, 11).

The cwEPR models were generated from spin labels attached to cysteines introduced to all transmembrane residues of MscS and measurement of O2 exposure (a reporter for lipid burial), Ni2+ exposure (a reporter of solvent accessibility), and mobility. The parameters derived from mobility, solvent, and lipid exposure were used to restrain molecular dynamics simulations. An advantage of cwEPR (31) and spectroscopic techniques in general is that they, unlike crystallography, can be performed on the protein embedded in liposomes, thus mimicking the natural environment more closely. For mechanosensitive channels adjusting lipid composition in the liposome prior to measurement has allowed experimental assessment of open and closed conformers (8, 9, 32, 33). cwEPR, which had the original closed crystal structure as a starting model, produced a closed structure (9) similar to the crystal structure (2) but different to the EMD closed conformer (7). On the other hand, the cwEPR open structure (8), which appeared simultaneously with the open crystal structure (thus did not use the open structure as a starting point), predicts a very different arrangement of helices to both the open crystal structure (6) and the open EMD structure (7). In the cwEPR gating model, TM3a rotates and translates around its own axis, removing L105 and L109 from the pore. TM1 and TM2 change their position but by a radically different rotation to that seen to the open crystal structure (6).

We evaluated the accuracy of the PELDOR technique for MscS by assessing as a control two spin-labeled positions attached to the soluble portion of MscS. S196R1 lies at the end of an α-helix in the αβ domain that is only described in the crystal structures and would be expected to be relatively inflexible. The predicted modal distance and distribution for the D1–2 vector, based on the crystal structures and the observed PELDOR data, are in excellent agreement (Fig. 4A). We do not consider our treatment of the experimental data to give robust measurements for the 1–3 and 1–4 vector, a point more fully discussed in Materials and Methods. S147R1 is located in the β domain and described by both cwEPR and crystal structures. The PELDOR modal (i.e., 1–2) distance and distribution is in close agreement with both crystal structures and the closed cwEPR structure, but there is no convincing fit to the open cwEPR structure (Fig. 4A). The EMD structures (7) were calculated without this domain and thus direct comparison is impossible. However, the “long” TM3 helix requires compensating adjustment in the β domain to avoid van der Waal clashes. PELDOR data indicate that any such perturbation does not change either the modal distance or distribution of S147R1. The excellent correspondence between the observed modal distance and distribution for both these “control” mutants and the predictions from MTSSLwizard analysis of the crystal structure validate our approach.

R128, L124 (both located on TM3b), and S58 (on TM1) were chosen because their modal distance and distributions are identical in both the open and closed crystal structures but are clearly different from predictions from the cwEPR and EMD models (Fig. 1D). Thus these three mutants provide an orthogonal test of the competing models. PELDOR analysis of each of these three mutants gives modal distances and distributions in excellent agreement with the crystal structures (Fig. 4B). For R128R1 the modal distance and distribution matches the closed and open EMD model. The measured modal distance but not distribution matches the closed cwEPR model. The open cwEPR model is inconsistent with the PELDOR data at this site. For L124R1 the modal distance and distributions of the open and closed EMD and open cwEPR models are inconsistent with PELDOR data. The closed cwEPR model does, however, match the data for L124R1 (Fig. 4B). For S58R1 the modal distance and distribution observed in PELDOR has no correspondence with any model from EMD or cwEPR (Fig. 4B).

D67R1 on TM2 and M47R1 on TM1 were chosen because these residues exhibit among the largest changes in modal distance and distribution between the open and closed crystal structures (Fig. 1B) and reside on different helices (Fig. 1A). In addition, these sites provide further assessment of the cwEPR and EMD models. Both open and closed cwEPR models are inconsistent with observed data for M47R1, with only the closed cwEPR having any match to the observed D67R1 spectra. Neither EMD model is consistent with the D67R1 data, and only the open EMD structure matches the M47R1 data (Fig. 4C). Combining our data (Fig. 4 A–C) we conclude that neither the cw-EPR nor the EMD derived models (closed or open) of MscS correspond to that which exists in solution. A further advantage of the D67R1 M47R1 pairing is that D67R1 gives rise to a decreased separation of the spin labels upon opening of MscS while M47R1 gives a longer separation (Fig. 1D), thus we should have detected any systematic over or under estimation of distance. Both mutants gave rise to modal distances and distributions that unambiguously match the open crystal structure (Fig. 4D). From these data, we conclude that, in solution, MscS has a helical arrangement matching that observed in the open crystal structure. D67R1 and M47R1 PELDOR data show a slightly broader distance distribution than is predicted for the open crystal structure, one possible interpretation of this is the presence of the closed form (minor contribution) as well as the open form (major contribution). Modeled distance distributions assuming various proportions of open and closed conformations indicate the closed conformation if present is at a maximum 15% for D67R1 and a maximum of 35% for M47R1 (Fig. S5B).

That PELDOR so clearly assigned MscS to the open state in DDM solution was unexpected. The first structure of MscS obtained by crystallization from Fos-14 detergent at pH 7.2 was in the closed form (2, 3), and we had assumed that this was the predominant species in detergent solution. We performed two further analyses to validate our finding. Firstly, measurement of D67R1 repurified in Fos-14 detergent (chemically very different to DDM) showed an identical PELDOR spectrum and distance distribution (Fig. 5A). The open structure in solution is not a simple consequence of the detergent used to extract the protein. Despite the identical structure, cwEPR gave profoundly different spectra (Fig. 5A). This would caution against simplistic structural interpretations of cwEPR line shape. Secondly, crystallographic analysis of two mutants were performed. Unbiased difference electron density for the transmembrane helices in the D67R1 structure match the arrangement of the open crystal (A106V) structure (Fig. 5B), validating the PELDOR measurement. A second mutant L124R1 also gives excellent agreement between the crystal structure and PELDOR data. The modal distance and distribution for L124R1 are identical in open and closed crystal structures; importantly the crystal structure of L124R1 is also clearly open. Because these crystals were obtained at pH 4.5, we investigated the sensitivity of MscS to pH by recording PELDOR spectra in DDM, and in Fos-14 at both low and neutral pH—no substantive differences were observed (Fig. S6). That both these new crystal structures are open we take as strongly supporting the conclusions of our PELDOR study.

A106V, L124R1, and D67R1 have all crystallized in the same open form [despite different detergents, pH, crystal packing, presence or absence of spin labels, and mutant location (TM2, TM3a, TM3b)]. PELDOR analysis of two key mutants, D67R1 and M47R1 show that in solution the arrangement of helices is unambiguously consistent with the open crystal structure; we conclude that crystal packing itself does not introduce notable distortions in the helical arrangement. Rather we conclude the open structure, first visualized in crystals, is in fact the predominant detergent solubilized form of MscS, perhaps reflecting the absence of the lateral pressure of the lipid bilayer.

The failure of the other approaches to correctly identify the solution conformation of MscS could be explained by postulating that the arrangement of the helices in the membrane are unique and different from those that exist in detergent micelle or in crystals. This could be tested by repeating EMD or cwEPR on detergent solubilized MscS, benchmarking these techniques. If detergent extraction, per se results in such dramatic helical rearrangement, then this would call into question the validity of all crystal structures and other biophysical approaches that rely on detergent extraction of protein. Alternatively the molecular models produced solely by EMD and cwEPR may require greater caution to avoid overinterpretation, and their reliability could be significantly improved by incorporation of metric data derived from PELDOR or other spectroscopic approaches.

MscS with its seven monomers, 21 transmembrane helices, and tightly regulated gating has served as a paradigm and experimental test bed for other ion channels. PELDOR has been utilized to study membrane proteins (16–18, 20, 21). By applying PELDOR to MscS we have now shown that it is possible to measure transmembrane helix separation at multiple sites within transmembrane helices themselves in a homoheptameric ion channel, an important anticipated development (34). Symmetric multimeric membrane proteins are often difficult to crystallize in all functionally relevant conformational states and other techniques must be employed to develop models. We have demonstrated that PELDOR is reliable in just such a complex system, and thus it provides both a crucial check of and restraint to other commonly used techniques allowing greater progress in membrane protein structural biology.

Materials and Methods

n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM), anagrade was obtained from Anatrace, Inc. (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was obtained from Formedium and (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) from Thermo Scientific, Ltd. S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate) (MTSSL) spin label was obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals, and (7-diethylamino-3-((4′-(iodoacetyl)-amino)phenyl)-4-methlycoumarin) (DCIA) was obtained from Invitrogen. All other chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were obtained from Sigma. Mutants were made with the Stratagene QuikChange™ protocol using pTrcYH6 as template. Primer sequences of MscS S58C have been described previously, and others are available on request. All mutants were sequenced on both strands.

Cell Viability Assays and Electrophysiological Studies.

Western blot analysis of whole-cell samples with Penta-His antibody (Qiagen) was carried out to examine the expression of mutants. For mutants MscS S58C, the survival assay of osmotic downshock has been published (23). For others, the assay was essentially the same as described previously with minor alteration. All survival experiments were performed using transformants of MJF641 (ΔyggB, ΔmscL, ΔmscK ΔybdG, ΔynaI, ΔybiO, ΔyjeP). Cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium, and both induced (0.3 mM IPTG added when OD650 nm ≈ 0.2) and uninduced cultures were studied. The culture was adapted to high osmolarity by growth to an OD650 nm of 0.3 in the presence of 0.3 M NaCl, and an osmotic downshock was then applied by a 1∶20 dilution into LB medium (shock) or the medium containing 0.3 M NaCl (control). After 10 min incubation at 37 °C, 5-μL serial dilutions of these cultures were spread onto LB-agar plates in the presence (control) or absence (shock) of 0.3 M NaCl. The survival rates were then assessed by counting the number of colonies after incubation overnight at 37 °C. Data are reported as means ± standard deviation.

Patch clamp recordings were conducted on membrane patches derived from giant protoplasts using the strain MJF429 (ΔyggB, ΔmscK) transformed with MscS plasmids as described previously (35). Gene expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 10 min before protoplast generation. Excised, inside-out patches were analyzed at a membrane potential of -20 mV with pipette and bath solutions containing 200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7. All data were acquired at a sampling rate of 50 kHz with 5-kHz filtration using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier and pClamp software (Molecular Devices). The pressure threshold for activation of the MscS channels was referenced against the activation threshold of MscL (PL∶PS) to determine the pressure ratio for gating as previously (36). Measurements have been conducted on patches derived from a minimum of two protoplast preparations. Pressure ratios are given as mean ± S.E.

Purification, Spin Labeling, and Structural Biology of MscS Single-Cysteine Mutants.

Different MscS single-cysteine constructs were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain MJF612 (ΔyggB, ΔmscL, ΔmscK, and ΔybdG). Cells were grown in 500 mL of LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 nm ≈ 0.9. The cultures were cooled to 25 °C and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h. The cell pellet was resuspended in PBS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline buffer, pH 7.5: containing 8 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of KCl, 1.15 g of Na2HPO4•7H2O, and 0.2 g of KH2PO4 per liter), supplemented with 0.2 mM freshly prepared phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF). After disruption of the cells with a French press at 18,000 psi, the suspension was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The membrane pellet was resuspended in buffer A (1.5% DDM, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 50 mM imidazole, 0.2 mM PMSF, and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor) and incubated at 4 °C. Non-solubilized membrane proteins were removed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was passed through a 15-mL column containing 0.5 mL of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA) agarose. The column was washed with 10 mL of degassed buffer B (0.05% DDM, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 50 mM imidazole) to remove nonspecifically bound proteins. TCEP dissolved in buffer B was then added to reduce MscS cysteines and subsequently MTSSL dissolved in buffer B was added at a concentration 10× in excess of the expected protein concentration and left to react o/night at 4 °C. Next morning freshly made MTSSL dissolved in buffer B 10×in excess of protein concentration was added to the column and left to react for another 2 h. Labelling efficiency was carefully monitored for each mutant (Fig. S4A). The elution followed with 10 mL of buffer C (as buffer B but with 300 mM imidazole), and 1 mL fractions were collected. The fractions were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and UV/vis absorption spectroscopy.

Size Exclusion Chromatography.

Fractions with the highest labeled protein content from the Ni2+-NTA column were applied to a 120-mL Superose 6 column (General Electrics Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer D (0.05% DDM, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl) to completely remove any excess of the spin label present. Labeled protein was eluted in the same buffer at 1 mL/ min. Protein concentration was monitored by absorption at 280 nm. The column was calibrated with the Biorad standard. Prior to PELDOR measurements protein buffer was exchanged to D2O buffer E (100 mM TES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05% DDM), and protein was concentrated to around 400 μM. Samples were diluted to 50% by the addition of ethylene glycol as cryoprotectant. Aliquots of 120 μl were transferred into quartz EPR tubes and quickly frozen as described earlier (14).

Mutants were purified and stored at 9–12 mg ml-1 in buffer D. Crystal trials were set up by hanging drop at 20 °C and involved mixing 1∶1 and 2∶1 volume of protein solution: precipitant equilibrated against a large volume of precipitant. Crystals grew to full size in two days for MscS D67R1 and eight days for MscS L124R1, respectively. The best crystals (visual inspection) were obtained using 0.07 M sodium citrate pH 4.5, 0.07 M NaCl, 22% v/v PEG 400 for MscS D67R1 and 0.07 M sodium citrate pH 4.5, 0.07 M NaCl, 25% v/v PEG 400 for MscS L124R1 as precipitant. Prior to data collection, crystals of both labeled MscS mutants were transferred into a solution containing 0.07 M sodium citrate pH 4.5, 0.07 M NaCl and 30% v/v PEG 400. Data for MscS D67R1 were collected at 100 K on a single crystal, which diffracted to a resolution of around 4.8 Å on I04-1 at Diamond (Oxford, UK). Data for MscS L124R1 were collected at 100 K on a single crystal, which diffracted to a resolution of around 4.7 Å on ID14-4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF). Data were indexed, integrated and merged using MOSFLM/SCALA (37) as implemented in CCP4 (38). The resolution limits were determined by the data statistics and the Wilson plot. The CCP4 program POINTLESS was used to assign space groups for both labeled MscS mutants as P212121. Data collection statistics are shown in Table S2. Both structures were solved using molecular replacement with the program PHASER using a model containing residues 118–280 (omitting TM1, TM2, TM3a, and part of TM3b) of the MscS A106V structure (PDB ID code 2VV5). Difference electron density maps were calculated based on this raw molecular replacement solution.

Continuous Wave EPR and PELDOR Spectroscopy.

Purified MscS labeled mutants in buffer E were concentrated to a concentration of 100 μM. Thirty μl was loaded in glass capillaries and RT CW EPR spectra of a 20-mW power and 9.5-G modulation amplitude were recorded. Spectra were averaged for 10 scans. CW EPR spectra were individually fitted using easyspin 4.0.0 (39). PELDOR experiments were performed using a Bruker ELEXSYS E580 spectrometer operating at X-band with a dielectric ring resonator and a Bruker 400U second microwave source unit. All measurements were made at 50 K with an overcoupled resonator. The video bandwidth was set to 20 MHz. The four-pulse, dead-time free, PELDOR sequence was used (40), with the pump pulse frequency positioned at the center of the nitroxide spectrum; the frequency of the observer pulses was increased by 80 MHz. The observer sequence used a 32 ns p-pulse; the pump π-pulse was typically 16 ns. The experiment repetition time was 3 ms, and the number of scans used was sufficient to obtain a suitable signal (typically > 100 scans) with 50 shots at each time point. Proton nuclear modulation averaging was used, which meant varying the first interpulse delay eight times and by 8 ns each time. Total experiment time varied according to the intensity of the observed echo but was typically 24–48 h. Full details in Table S3. The experimentally obtained time domain trace was processed so as to remove any unwanted intermolecular couplings, which is called the background decay. Tikhonov regularization (25, 41) was then used to simulate time trace data that give rise to distance distributions, P(r), of different peak width depending on the regularization factor, α. The α-term used was judged by reference to a calculated L curve. The most appropriate α-term to be used is at the inflection of the L curve, because this provides the best compromise between smoothness (artifact suppression) and fit to the experimental data. PELDOR data were analyzed using the DeerAnalysis 2010 software package (25). The dipolar coupling evolution data were corrected for background echo decay using a homogeneous 3D spin distribution. The starting time for the background fit was optimized to give the best fit Pake pattern in the Fourier transformed data and the lowest rmsd background fit.

The spin–spin interaction in a multispin system is the product of the pair interactions. DeerAnalysis 2010 (25) treats such multiple interactions in the form of their sums (not products) leading to artifacts (42). On a multimeric model systems such artifacts did not significantly affect the data or interpretation of the D1–2 vector (43). Similarly crystallography showed that PELDOR of the octameric spin labeled Wza gave reliable D1–2 vector information. Using DeerAnalysis on both Wza and model systems showed broadening, decreased intensity and shifting of the modal distance for the 1–3 and 1–4 distances, consistent with the limitations of current approaches for multimeric systems. In this work we rely only on the D1–2 vector.

Prediction of Distance Distributions for the Different Models.

In silico spin labeling, rotamer conformation searching, and distance measurements were all carried out within the software package Pymol (www.pymol.org) using the MTSSLwizard plugin (27). MTSSLwizard has been extensively benchmarked against test data and produces excellent results. Rotamer conformations that were allowed according to suggested defaults. Distance distributions were obtained by binning the data into 1-Å bins. The atomic coordinates of MscS used for this modeling procedure were as follows: crystal structures 2OAU (2), 2VV5 (6), the closed and open structures generated by molecular dynamics simulations (7, 30) and the EPR closed (9, 28) and open (8) structures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Drs. Samantha Miller, Tim Rasmussen, and Ulrike Schumann for provision of strains and plasmids; Dr. Jesko Koehnke for help in mounting crystals; Dr. Michelle Edwards for advice on electrophysiology; and Ms. Frances Goff for assistance. The work was funded by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/H017917/1 to J.N.H., O.S., and I.R.B., by a Wellcome Trust Grant WT092552MA to J.H.N. and I.R.B. and equipment through Wellcome Trust Capital Award. We thank S. Sukharev for EMD conformers of MscS and E. Perozo for the EPR conformers of MscS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 15983 (volume 109, number 40).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1202286109/-/DCSupplemental.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4AGE (D67R1) and 4AGF (L124R1)].

References

- 1.Levina N, et al. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS MscL mechanosensitive channels: Identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:1730–1737. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bass RB, Strop P, Barclay M, Rees DC. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli MscS a voltage-modulated and mechanosensitive channel. Science. 2002;298:1582–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1077945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinbacher S, Bass R, Strop P, Rees DC. Structures of the prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS. Curr Top Membr. 2007;58:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anishkin A, Sukharev S. Water dynamics and dewetting transitions in the small mechanosensitive channel MscS. Biophys J. 2004;86:2883–2895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74340-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards MD, et al. Pivotal role of the glycine-rich TM3 helix in gating the MscS mechanosensitive channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:113–119. doi: 10.1038/nsmb895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, et al. The structure of an open form of an E. coli mechanosensitive channel at 3.45 Å resolution. Science. 2008;321:1179–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.1159262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akitake B, Anishkin A, Liu N, Sukharev S. Straightening and sequential buckling of the pore-lining helices define the gating cycle of MscS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasquez V, Sotomayor M, Cordero-Morales J, Schulten K, Perozo E. A structural mechanism for MscS gating in lipid bilayers. Science. 2008;321:1210–1214. doi: 10.1126/science.1159674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasquez V, et al. Three-dimensional architecture of membrane-embedded MscS in the closed conformation. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belyy V, Anishkin A, Kamaraju K, Liu N, Sukharev S. The tension-transmitting ‘clutch’ in the mechanosensitive channel MscS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:451–458. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kung C, Martinac B, Sukharev S. Mechanosensitive channels in microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:313–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naismith JH, Booth IR. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels-MscS: Evolution’s solution to creating sensitivity in function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:157–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-101211-113227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiemann O, Prisner TF. Long-range distance determinations in biomacromolecules by EPR spectroscopy. Q Rev Biophys. 2007;40:1–53. doi: 10.1017/S003358350700460X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagelueken G, et al. PELDOR spectroscopy distance fingerprinting of the octameric outer-membrane protein Wza from Escherichia coli. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:2904–2906. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reginsson GW, Schiemann O. Pulsed electron–electron double resonance: Beyond nanometre distance measurements on biomacromolecules. Biochem J. 2011;434:353–363. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altenbach C, Kusnetzow AK, Ernst OP, Hofmann KP, Hubbell WL. High-resolution distance mapping in rhodopsin reveals the pattern of helix movement due to activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7439–7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802515105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endeward B, Butterwick JA, MacKinnon R, Prisner TF. Pulsed electron–electron double-resonance determination of spin-label distances and orientations on the tetrameric potassium ion channel KcsA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15246–15250. doi: 10.1021/ja904808n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph B, Jeschke G, Goetz BA, Locher KP, Bordignon E. Transmembrane gate movements in the type II ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importer BtuCD-F during nucleotide cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41008–41017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borbat PP, et al. Conformational motion of the ABC transporter MsbA induced by ATP hydrolysis. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilger D, Polyhach Y, Jung H, Jeschke G. Backbone structure of transmembrane domain IX of the Na+/proline transporter PutP of Escherichia coli. Biophys J. 2009;96:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dockter C, et al. Refolding of the integral membrane protein light-harvesting complex II monitored by pulse EPR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18485–18490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906462106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzikovski BG, Borbat PP, Freed JH. Channel and nonchannel forms of spin-labeled gramicidin in membranes and their equilibria. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:176–185. doi: 10.1021/jp108105k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller S, Edwards MD, Ozdemir C, Booth IR. The closed structure of the MscS mechanosensitive channel. Cross-linking of single cysteine mutants. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32246–32250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller S, et al. Domain organization of the MscS mechanosensitive channel of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2003;22:36–46. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeschke G, et al. DeerAnalysis2006—A comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR data. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:473–498. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeschke G. Distance measurements in the nanometer range by pulse EPR. Chemphyschem. 2002;3:927–932. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20021115)3:11<927::AID-CPHC927>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagelueken G, Ward R, Naismith JH, Schiemann O. MtsslWizard: In silico spin-labeling and generation of distance distributions in PyMOL. Appl Magn Reson. 2012;42:377–391. doi: 10.1007/s00723-012-0314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malcolm HR, Heo YY, Elmore DE, Maurer JA. Defining the role of the tension sensor in the mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Biophys J. 2011;101:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee AG. Biological membranes: The importance of molecular detail. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anishkin A, Akitake B, Sukharev S. Characterization of the resting MscS: Modeling and analysis of the closed bacterial mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Biophys J. 2008;94:1252–1266. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakrapani S, Sompornpisut P, Intharathep P, Roux B, Perozo E. The activated state of a sodium channel voltage sensor in a membrane environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5435–5440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914109107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perozo E, Cortes DM, Sompornpisut P, Kloda A, Martinac B. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channels. Nature. 2002;418:942–948. doi: 10.1038/nature00992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perozo E, Cuello LG, Cortes DM, Liu YS, Sompornpisut P. EPR approaches to ion channel structure and function. Ion Channels. 2002;245:146–164. doi: 10.1002/0470868759.ch10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mchaourab HS, Steed PR, Kazmier K. Toward the fourth dimension of membrane protein structure: Insight into dynamics from spin-labeling EPR spectroscopy. Structure. 2011;19:1549–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Moe PC, Martinac B, Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–482. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)94027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Schroeder MJ, Nagle SK, Kung C. Single residue substitutions that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11652–11657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.CCP4. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoll S, Schweiger A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeschke G, Pannier M, Godt A, Spiess HW. Dipolar spectroscopy and spin alignment in electron paramagnetic resonance. Chem Phys Lett. 2000;331:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiang YW, Borbat PP, Freed JH. The determination of pair distance distributions by pulsed ESR using Tikhonov regularization. J Magn Reson. 2005;172:279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeschke G, Sajid M, Schulte M, Godt A. Three-spin correlations in double electron–electron resonance. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:6580–6591. doi: 10.1039/b905724b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bode BE, et al. Counting the monomers in nanometer-sized oligomers by pulsed electron–electron double resonance. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6736–6745. doi: 10.1021/ja065787t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]